The association between bipolar disorder (BD) and avascular necrosis of the femoral head and neck (AVNHNF) remains unclear. We aimed to investigate the risk of AVNHNF among different polarity of BD.

MethodsBetween 2001 and 2010, patients with BD were selected from the Taiwan National Health Research Database. The controls were individuals without severe mental disorder who were matched for demographic, medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Cox regression analysis was used to estimate the risk of AVNHNF, with adjustments for demographics, comorbidities, exposure to corticosteroids, and all-cause clinical visits.

ResultsA total of 84,721 patients with BD and 169,442 controls were included. Patients with BD demonstrated a 1.92-fold (95% of confidence interval: 1.21–3.04) higher risk of AVNHNF compared with the controls. The risk was increased to 7.91-fold (4.32–14.49) in patients with severe BD compared with the controls. Importantly, patients with severe bipolar depression were associated with a 14.23-fold higher risk of AVNHNF compared with the controls, while those with sever bipolar mania were associated with a 3.55-fold higher risk. Compared with the controls with alcohol use disorder (AUD), patients with BD and comorbid AUD were associated with a 2.0-fold higher risk of AVNHNF. Finally, long-term use of atypical antipsychotics was associated with a decreased risk of AVNHNF).

ConclusionClinicians should be aware of the increased risk of AVNHNF among patients with BD. This increased risk was associated with disorder severity, polarity, and comorbidity with AUD, and attenuated by long-term atypical antipsychotic treatment.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head and neck (AVNHNF) is a degenerative condition involving cell death of the bone or marrow, resulting in collapse of the articular surface.1 The natural progression of AVNHNF starts with infarction of the subchondral bone of the femoral head, flattening of the articular cartilage, narrowing of the joint space, subsequent osteoarthrosis of the hip, and progression to irreversible degeneration of the hip joint.2-4 AVNHNF is a debilitating, potentially disabling disease that typically affects people younger than 50 years old4; it is the cause of approximately 10% of total hip replacements per year in the United States.5 To date, the etiology of AVNHNF is still poorly understood; however, several risk factors have been reported, including traumatic injury, radiation injury, myeloproliferative disorders, sickle cell disease, coagulation disorders, infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), pregnancy, and specific medications (e.g., corticosteroids).6-9

Previous studies have linked AVNHNF to mental health problems, showing that depression, anxiety, and pain catastrophizing were significantly associated with hip pathology, including osteoarthritis and AVN.10-12 A previous study found that 48% of patients with depression developed AVN, while only 9% of patients without depression developed AVN after an operation for femoral neck fractures.12 Alcohol use has also been reported as a major risk factor for AVNHNF. Alcohol abuse has been reported to account for approximatively 30 to 40% of patients who developed hip or femoral osteonecrosis.13-15 There seems to be a dose response relationship between alcohol use and AVNHNF; however, the threshold for the threshold level of alcohol consumption associated with the development of avascular necrosis has not been clearly established.16 Previous literature has reported multifactorial etiologies for the association between alcohol use and AVNHNF, such as genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and medical comorbidities.16,17

Although AVNHNF has been previously associated with depression, it remains understudied in people with bipolar disorder (BD), which is also a major affective disorder with an approximate life prevalence of 1.06% for BD type 1 and 1.57% for BD type 2.18 BD is characterized by extreme mood changes, from depression to mania, and continues to be deleterious to quality of life and can even lead to disability.19,20 Several factors may contribute the association between BD and AVNHNF. As the risk factors of AVNHNF are reported (e.g., SLE, HIV infection or use of corticosteroid),6-9 SLE is also identified as the independent factor associated with BD.21 In addition, the prevalence of BD type 1 in the HIV patients shows 5.6%, which is almost six times higher than the US general population (1%).22 Furthermore, patients treated with corticosteroid have risk to develop mood instability, anxiety, depression, or mania.23,24 Corticosteroids have been reported to be associated with various aspects of brain physiology, including neurotoxicity.25 On the other hand, chronic corticosterone administration results in dysfunction of the medial prefrontal cortex,26 where is associated with BD.27 To date, no studies have examined the role of BD's severity and polarity (i.e., bipolar depression or bipolar mania) in the risk of AVNHNF. In addition, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is reported to be highly prevalent in patients with BD.28 However, the potential joint effect of BD and AUD on the risk of AVNHNF remains unknown. The aim of the current study was to investigate the risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD using a nationwide longitudinal study design. We hypothesized that patients with BD would be associated with an increased risk of severe AVNHNF, and that this risk would be modified by the severity and the polarity of BD and its associated comorbidities and psychotropic treatment.

Materials and methodsData sourceThis study has been approved by an Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (2018-07-016AC). Taiwan's National Health Insurance is a mandatory universal health insurance program which offers comprehensive medical care coverage to all Taiwanese residents (more than 23 million people). The Taiwan National Health Research Institute (NHRI) manages the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which is a database of all insurance claims in Taiwan and consists of healthcare data from >99% of the population of Taiwan. The NHRI audits and releases the NHIRD for scientific and study purposes.29,30 Individual medical records included in the NHIRD are anonymized to protect patient privacy. Comprehensive information on insured individuals is included in the database, including demographic data, dates of clinical visits, diagnoses, prescriptions, and medical interventions. The diagnostic codes used are based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The NHIRD has been used extensively in previous epidemiological studies.31-34

Inclusion criteria for patients with BD and the control groupWe enrolled adults aged ≥20 years who received a diagnosis of BD (ICD-9-CM codes: 296 except 296.2x, 296.3x, 296.9x, and 296.82) between January 1st 2001 and December 31st 2010, from board-certified psychiatrists based on a comprehensive diagnostic interview and their clinical judgement, and who had no history of avascular necrosis (ICD-9-CM code: 733.4) before enrollment. The time of enrollment was defined as the time of a diagnosis with BD. The controls were randomly selected after eliminating the study cases, individuals who had been diagnosed with severe mental disorders (ICD-9-CM codes: 295, 296) at any time, and individuals with avascular necrosis before enrollment.35 The controls were matched (1:2) according to the following criteria: age (± 1 year)-, sex-, time-of-enrollment-, medical comorbidity-, income (levels 1–3 per month: ≤15,840 New Taiwanese Dollars (NTD), 15,841–25,000 NTD, and ≥25,000 NTD)-, and level-of-urbanization (levels 1–5, most to least urbanized, a proxy for healthcare availability in Taiwan). The primary outcome variable in this study was the first hospitalization for severe AVNHNF during the follow-up period (from enrollment to December 31st 2011 or death), which was defined as the principal diagnosis at discharge based on the ICD-9 code, 733.42. A diagnosis of AVNHNF was given by board-certified orthopedic surgeons.

We controlled for potential confounding factors for the association between BD and the risk of severe AVNHNF, including exposure to corticosteroids (≥90 days vs <90 days) and psychiatric and medical comorbidities. We identified the 90 days of exposure as a long-term exposure of corticosteroids because long-term exposure to corticosteroids was considered an AVNHNF risk factor.36 The investigated psychiatric comorbidities were substance use disorder (SUD) and AUD. The investigated medical comorbidities were hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, femoral neck fracture, and smoking. Additionally, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and all-cause clinical visits were provided for the BD cohort and the controls. The CCI consisting of 22 physical conditions was used to determine the systemic health condition of all enrolled subjects.37 Higher scores on the CCI indicate a more severe physical condition and consequently, a worse health status.

Over the follow-up period, the use of psychotropic medications (antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and atypical antipsychotics) was divided into 3 subgroups: non-users (cumulative defined daily dose [cDDD] during the follow-up period <30), short-term users (cDDD = 30–364), and long-term users (cDDD ≥365). Antidepressants used included fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, bupropion, and mirtazapine. Mood stabilizers used included lithium and anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, topiramate, and gabapentin), and atypical antipsychotics including aripiprazole, risperidone, paliperidone, olanzapine, amisulpride, ziprasidone, clozapine, and quetiapine.

The primary outcome of the current study is the risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD compared with controls. The frequency (times per year) of psychiatric admission for BD was assessed, and regarded as an indicator of disease severity for BD in our study. The disease severity was also stratified to identify its effect on the risk of AVNHNF among patients with BD. Furthermore, the frequency of psychiatric admission for manic/mixed and depressive episodes of BD were separately examined so that the association between manic/mixed and depressive episodes and severe AVNHNF risk could be clarified. In addition, all-cause clinical visits (the number of clinical visits per year) for the BD cohort and the matched-controls were included as a variable to account for potential detection bias.

Statistical analysisFor between-group comparisons, the F test was used for continuous variables and Pearson's χ2 test for nominal variables, where appropriate. Cox regression analysis with full adjustment for demographic data (age, sex, income, level of urbanization), medical comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, SUD, AUD, femoral neck fracture and smoking), exposure to corticosteroids, CCI score, and all-cause clinical visits was used to investigate the AVNHNF risk between the BD and control groups. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to identify the level of risk. As AUD is a major risk factor for severe AVNHNF, subgroup-analysis stratified by AUD was also performed. Furthermore, Cox regression analyses were used to clarify the association between the frequency of psychiatric admission for BD (total, manic/mixed, and depressive episodes) and the risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD. Finally, we examined the association between psychotropic medications (long-term use vs. short-term use vs. non-use) and severe AVNHNF risk among patients with BD. A 2-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 17 software (Chicago: SPSS Inc.) and Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Data availability statementThe NHIRD was released and audited by the Department of Health and Bureau of the NHI Program for the purpose of scientific research (https://nhird.nhri.org.tw/). The NHIRD can be obtained via a formal application which is regulated by the Department of Health and Bureau of the NHI Program.

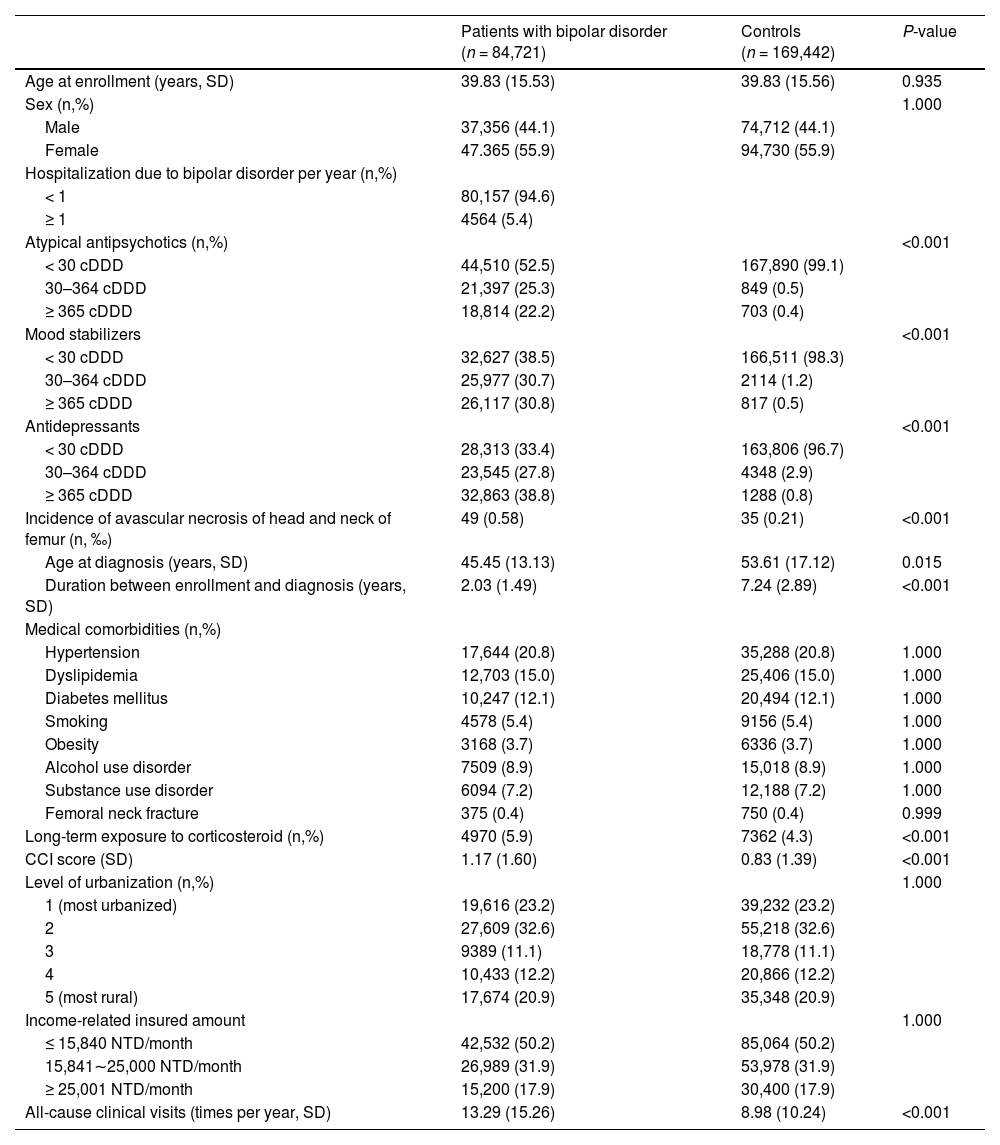

ResultsIn the current study, we recruited 84,721 patients with BD and 169,442 controls without severe mental disorders, with mean ages of 39.83 years (standard deviation (SD): 15.53) and 39.83 years (SD: 15.56), respectively. Patients with BD had a significantly higher incidence of severe AVNHNF (0.58% vs 0.21%, p<0.001), a younger age at severe AVNHNF diagnosis (45.45 vs 53.61 years, p = 0.015), and a shorter time between enrollment and diagnosis of severe AVNHNF (2.03 vs 7.24 years, p<0.001) compared with the controls. Patients with BD also had a higher proportion of long-term exposure to corticosteroids (5.9% vs 4.3%, p<0.001), higher CCI scores (1.17 vs 0.83, p<0.001), and higher annual all-cause clinical visits (13.29 vs 8.98, p<0.001) compared with the controls. The remaining variables revealed non-significant differences. Detailed data is shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and incidence of avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur among patients with bipolar disorder and controls.

SD: standard deviation; NTD: new Taiwan dollar; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; cDDD: cumulative defined daily dose.

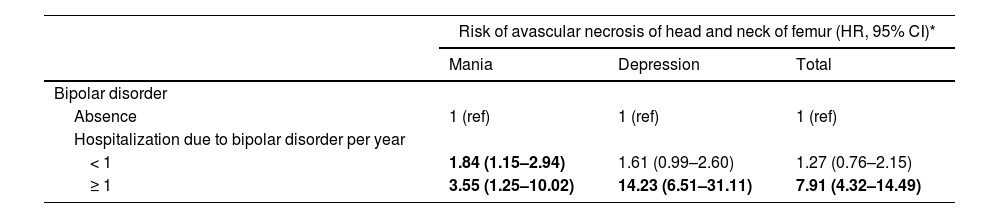

Patients with BD had higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with the controls (1.92 HR, 95% Cl: 1.21–3.04), with adjustment for demographics, psychiatric and medical comorbidities, corticosteroid exposure, CCI score, and all-cause clinical visits (Table 2). When the severity of BD was considered (assessed by number of psychiatric hospitalizations for BD per year), patients with severe BD (≥1 hospitalization for BD per year) demonstrated a higher risk of severe AVNHNF (7.91 HR, 95% Cl: 4.32–14.49) than the controls; however, the increase in risk was not significant (1.27 HR, 95% Cl: 0.76–2.15) in patients with <1 hospitalization for BD per year (Table 2).

Risk of developing avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur among patients with bipolar disorder and controls, stratified by disease severity.

| Risk of avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur (HR, 95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mania | Depression | Total | |

| Bipolar disorder | |||

| Absence | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Hospitalization due to bipolar disorder per year | |||

| < 1 | 1.84 (1.15–2.94) | 1.61 (0.99–2.60) | 1.27 (0.76–2.15) |

| ≥ 1 | 3.55 (1.25–10.02) | 14.23 (6.51–31.11) | 7.91 (4.32–14.49) |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

When stratified by psychiatric hospitalization for bipolar mania and bipolar depression, patients with severe bipolar depression (≥1 hospitalization for bipolar depression per year) demonstrated a higher risk of severe AVNHNF (14.23 HR, 95% Cl: 6.51–31.11) compared with the controls, however the risk was not significantly increased (HR 1.61, 95% Cl: 0.99–2.60) in patients with <1 hospitalization for bipolar depression per year. Importantly, the risk of severe AVNHNF was significantly increased in patients with both severe bipolar mania (3.55 HR, 95% Cl: 1.25–10.02) and less severe bipolar mania (1.84 HR, 95% Cl: 1.15–2.94).

When stratified by AUD comorbidity, patients with BD and AUD demonstrated a higher risk of severe AVNHNF (2.0 HR; 95% Cl: 1.05–3.84) compared with the controls with AUD; however the risk of severe AVNHNF was not significantly increased in patients with BD without AUD, compared with the controls without both BD and AUD (1.49 HR; 95% Cl: 0.72–2.95) (Table 3). To estimate the impact of gender difference on the risk of severe AVNHNF, we found that male was associated with the elevated severe AVNHNF risk. In addition, the sex effect on severe AVNHNF risk was particularly observed among patients with alcohol use disorder (Table 3).

The effect of alcohol use disorder on the Risk of developing avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur.

| Risk of avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur (HR, 95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| With alcohol use disorder | Without alcohol use disorder | Total | |

| Bipolar disorder | |||

| Absence | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Presence | 2.00 (1.05–3.84) | 1.49 (0.75–2.95) | 1.92 (1.21–3.04) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Male | 2.50 (1.00–6.25) | 1.73 (0.88–3.42) | 1.86 (1.10–3.16) |

SHR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

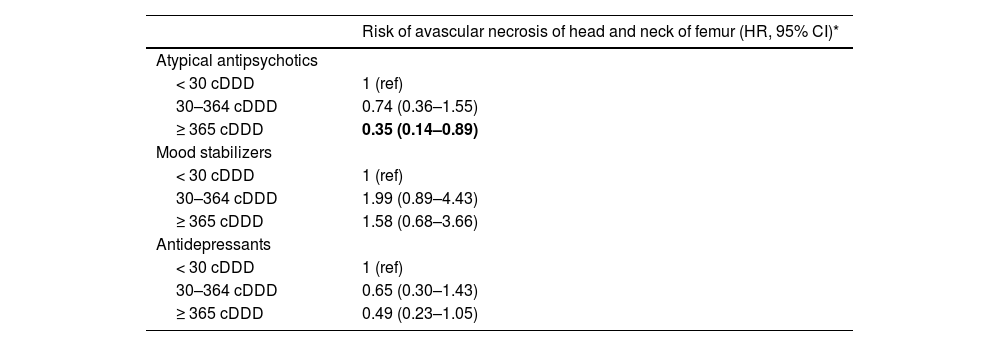

Finally, we examined whether the use of psychotropic medications was associated with the risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD. We found that long-term users (cDDD ≥365) of atypical antipsychotics were associated with a decreased risk in severe AVNHNF (0.35 HR, 95% Cl: 0.14–0.89) compared with non-users of atypical antipsychotics (cDDD <30). However, all other associations were not statistically significant (Table 4).

Risk of avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur categorized by different groups of cumulative defined daily dose with psychotropic agents among patients with bipolar disorder.

| Risk of avascular necrosis of head and neck of femur (HR, 95% CI)* | |

|---|---|

| Atypical antipsychotics | |

| < 30 cDDD | 1 (ref) |

| 30–364 cDDD | 0.74 (0.36–1.55) |

| ≥ 365 cDDD | 0.35 (0.14–0.89) |

| Mood stabilizers | |

| < 30 cDDD | 1 (ref) |

| 30–364 cDDD | 1.99 (0.89–4.43) |

| ≥ 365 cDDD | 1.58 (0.68–3.66) |

| Antidepressants | |

| < 30 cDDD | 1 (ref) |

| 30–364 cDDD | 0.65 (0.30–1.43) |

| ≥ 365 cDDD | 0.49 (0.23–1.05) |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; cDDD: cumulative defined daily dose.

The main findings of the current study are summarized as follows: (i) patients with BD were associated with a 1.92-fold higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with controls without severe mental disorders, after adjusting for potential confounding factors; (ii) the severity of BD and the polarity of BD may play an important role in the association between BD and the risk of severe ANVHNF. Patients with severe BD were associated with a 7.91-fold higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with the controls, while patients with severe bipolar depression were associated with a 14.23-fold higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with the controls; (iii) patients with severe bipolar mania were associated with a 3.55-fold higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with the controls; (iv) the risk of severe AVNHNF was increased 2-fold in patients with both BD and AUD; and (v) patients with BD taking long-term atypical antipsychotic treatment were associated with a decreased risk of severe AVNHNF compared with those patients with BD receiving <30 cDDD atypical antipsychotics.

Several potential mechanisms could explain the increased risk of AVNHNF in patients with BD. Firstly, traumatic injury is a well-known risk factor for severe AVNHNF,38 and patients with BD have been associated with an increased incidence of accidental injury or bone fracture, which could in turn lead to AVNHNF.38 According to a recent menta-analysis, patients with BD have 1.85-fold (95% of CI: 1.17–2.94) risk of traumatic injury than control group (incidence for BD: 12∼13%; for control group: 6∼7%).38 Prior traumatic brain injury was also reported to be associated with psychiatric disorders, including depression and BD.38 A systemic review demonstrated that an increased fracture risk was observed in patients with BD, independent of demographic characteristics and medication use.39 A population-based study in Taiwan also found that BD is associated with an increased risk of fracture.40 The link between BD and traumatic injury or bone fracture is complicated and common characteristics such as hyperactivity, distractibility, impulsivity, irritable mood and risk-taking behaviors, mean patients with BD may be associated with an increased risk of accidental injury or fracture.41-44 Moreover, health-risk behaviors such as smoking and inadequate dietary intake, were commonly seen in patients with BD and may increase their risk of fracture.45,46 Secondly, the association between BD and severe AVNHNF may be mediated by medical comorbidities, such as SLE. Association between SLE and mood disorder may result from antibody mediated vascular injury in the CNS or antibody mediated neuronal damage.47,48 Regarding the association between SLE and severe AVNHNF, it may be related to the microvascular thrombosis and vasculitis induced damage in bone tissues.49 In addition, medications used for the treatment of BD can also be associated with an increased risk of fracture. For instance, a recent meta-analysis indicated that the use of antiepileptic drugs was highly associated with an increased risk of fracture, and these drugs are commonly prescribed as mood stabilizers for patients with BD.50

The current study showed that more admissions per year due to BD could act as an exacerbating risk factor for severe AVNHNF, indicating that a higher severity of BD is associated with a greater risk of severe AVNHNF. A previous study indicated that an increased previous hospitalization rate and higher severity of disease predicted a higher risk of re-admission among patients with BD.51 Moreover, physical comorbidities are associated with re-admissions due to psychiatric disorders, including BD.52 Although the association or etiologies for the impact of psychiatric admissions on the association between BD and severe AVNHNF has not been reported, we suppose that more hospitalizations for BD may be related to increased physical problems, including traumatic injury, and it may result in increased risk of severe AVNHNF. However, further research is warranted to explore the possible etiologies. More hospitalizations also indicate a higher severity of BD, where accidental injury may be associated with the characteristics of BD. Although severer bipolar depression and bipolar mania were both associated with an elevated risk of severe AVNHNF, we found a divergence in the HR between them, which was an interesting finding. We reported that the HR for bipolar depression had a higher severity of 14.23, which was even higher than the HR (3.55) for severe bipolar mania. Regarding bipolar mania, behavioral manifestations or impulsivity may expose these patients to an increased risk of physical injury, thereby increasing their risk of fracture. However, the higher HR of bipolar depression may be contributed to by other factors, such as malnutrition, lower activity, or antidepressants. Previous evidence has demonstrated that Vitamin D deficiency is linked to depressive disorders,53 and Vitamin D deficiency is also associated with osteonecrosis and osteoporosis.54,55 Since hypoactivity is characterized by the symptoms of bipolar depression,56 low levels of physical activity may increase the risk of osteoporosis and bone loss, leading to fracture.57 In addition, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are often prescribed during bipolar depression, are associated with an increased fracture risk.58 For instance, a meta-analysis demonstrates that patients taking SSRIs have 1.40-fold risk (95% of CI: 1.22–1.61) of any fractures than control group.59 A preclinical study has shown that SSRIs affect osteoblast formation and function.60 The above findings reveal an association between bipolar depression and poor bone health, which may result in the increased risk of severe AVNHNF. However, the definite etiology for the divergence in risk of severe AVNHNF between bipolar mania and bipolar depression remains unclear. With the multidimensional factors associated with brain metabolism, neurotransmitter, and immune function between bipolar mania and depression,61 further studies are warranted to clarify the detailed etiologies behind the divergences of risk for severe AVNHNF.

On the other hand, patients with BD were associated with a 1.92-fold higher risk of severe AVNHNF compared with the controls, and this risk was increased 2-fold in patients with BD comorbid with AUD. Importantly, the prevalence of AUD is reported as 42% among patients with BD,62 which is much higher than general population ranging from 1.4% to 8.6%.63,64 The etiologies of alcohol toxicity in the bone marrow and genetic factors of osteonecrosis are complicated.16,17,65,66 Animal studies have shown that treatment with alcohol in the bone marrow increased pressure and adipogenesis and decreased hematopoiesis, resulting in osteonecrosis of the femoral head.16,66 Biomedical studies have also reported that miRNA could be aberrantly involved in alcohol-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head with bone or vessel gene targets, including IGF2, PDGFA, and VEGF.65 Furthermore, previous literature has reported a complex network of signals between alcohol and bone remodeling, and intercellular communication between osteoclasts and the immune system may be a potential mechanism for osteonecrosis of the femoral head.67 In addition, severe AVNHNF could be associated with traumatic injury or fracture caused by alcohol use, such as road injury, violence, self-harm, falls, and other accidents.68,69 Given the high comorbidity rate between AUD and BD,62 specific intervention and treatment for AUD may be helpful to reduce the risk of severe AVNHNF.

Finally, we determined that long-term use of atypical antipsychotics could reduce the risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD. According to treatment guidelines, atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine and aripiprazole, are the first-line treatment choice for patients with BD.70,71 However, our findings are not comparable with previous studies, which indicated a higher risk of fracture in patients receiving treatment with either typical or atypical antipsychotics.72,73 These divergences may be due to either of the following two reasons. First, previous studies focusing on the risk of fracture for antipsychotics mainly recruited patients with schizophrenia,72,73 which may have etiological differences from BD. Second, there may be undiscovered factors affecting the association between antipsychotics and fracture, given that several studies do not support this association.74,75 The authors suppose that regular treatment with atypical antipsychotics may be beneficial in controlling the symptoms of BD, such as hyperactivity and risk-taking behaviors. Therefore, it may reduce the occurrence of traumatic injury or fracture, which are associated with severe AVNHNF. However, this hypothesis deserves further investigation to clarify the complicated etiologies of the association between BD and severe AVNHNF.

The current study had several limitations. First, due to limitations of the NHIRD, interactions between BD, AUD, number of hospitalizations, use of atypical antipsychotics and subsequent AVNHNF could not be clearly identified with mediation or moderation analysis. Second, although we have adjusted for multiple factors (demographic data, medical comorbidities, corticosteroid exposure, CCI score, and all-cause clinical visits) related to the risk of severe AVNHNF, residual confounding factors may still exist in our study, such as ethnicity. However, this naturalistic observation may reflect clinical practice in the real world. Third, the limited follow-up duration may limit the interpretation of the risk of severe AVNHNF, since the period of onset of avascular necrosis is between 20 and 40 years.

ConclusionsIn the present study, we determined that patients with BD are at a significant risk of subsequent severe AVNHNF. Our results extend the findings of previous studies, by demonstrating the risk of traumatic injury or fracture among patients with BD. In addition, we also found that disorder severity, mood swings, AUD, and long-term use of atypical antipsychotics had a significant impact on the association between BD and severe AVNHNF. These findings highlight the clinical implications of the effective management of BD and comorbid AUD, showing that it could help decrease the subsequent risk of severe AVNHNF among patients with BD. Patients comorbid with BD and AUD may result in poor clinical outcome, such as attempted suicide.76 With the therapeutic challenge in the treatment of BD with comorbid AUD, clinicians should carefully develop strategies in choosing proper medications.77 As the benefit of long-term use of atypical antipsychotics, our study suggests the necessity of regular treatment for patients with BD, which can be improved by enhancing medical adherence and insight. Further neuro-biological investigations are needed to better clarify the etiologies behind the association between BD and severe AVNHNF.

Role of the funding sourceThe study was supported by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V106B-020, V107B-010, V107C-181, V108B-012, V110C-025, V110B-002), Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-109-21, CI-109-22, CI-110-30) and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (107-2314-B-075-063-MY3, 108-2314-B-075-037, 110-2314-B-075-026, 110-2314-B-075-024-MY3). The funding source had no role in any process of our study.

DisclosureThe authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Patient consent statementThe requirement for patient consent was waived because the data used in this study were anonymized and derived wholly from a sizeable national database.

Ethical publication statementThis study protocol was reviewed and accepted by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (approval number: TPEVGH-IRB-2018-07-016AC). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

The authors thank Mr I-Fan Hu, MA (Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London; National Taiwan University) for his friendship and support. Mr Hu declares no conflicts of interest.