To examine the prevalence of two ISAAC (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood) asthma indicators in 7 European countries and their relationship with mental health disorders in children 6–12 years.

MethodsA cross-sectional survey of 5712 school children aged 6–12 years using a video Self-administered instrument: Dominic Interactive and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for parents and teachers. Asthma indicators were 12 month “Wheezing or whistling in the chest” (WWC) and “Severe Asthma” (SA) based on number of attacks of wheezing, sleep disturbance due to wheezing, and limits to speech.

ResultsOn average 7.31% of the children had WWC, from 15.09% in Turkey to 1.32% in Italy; SA 2.22% on average ranged from 4.78% in Turkey to 0% in Italy. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) from child self-reports was significantly associated with WWC and SA even after adjustment for covariates. Based on parent and teacher combined reports, emotional problems were found to have significant associations with 12-month WWC after adjustment, as well as “any problems” which summarized externalizing and internalizing disorders Emotional, hyperactivity, conduct disorders were not associated with SA.

ConclusionAsthma indicators very much differ across countries. Asthma indicators are associated with childhood GAD. Childhood self-reported mental health seems more related to Asthma indicators than parents/teachers combined reports.

Asthma is a disease that affects an estimated 339 million people worldwide and is in the top 20 causes of years lived with disability.1 The severity of asthma could reach life-threatening attacks; hospital admissions and mortality are among its severity indicators, showing great variance throughout the world.2 Asthma is then associated with a high disease burden, along with rising global incidence and prevalence.3 Furthermore, a wide range of comorbidities have been associated with asthma status, especially in children.4,5 These include conditions such as rhinitis, diseases of the gastric and esophageal systems, hormonal disorders, obesity, sleep disorders, and lastly, mental disorders.4,6 Evidence exists that there is a possible bidirectional relationship between asthma and mental health disorders in children and adults, both ways.

A 2004 meta-analysis found that adult and child/adolescent populations with asthma appear to have a high prevalence of anxiety disorders.7 Another 2018 meta-analysis of allergic disorders and depression found that in an asthma subgroup the RR of depression was higher in adults and children compared to their non-asthmatic peers.8 Two meta-analyses found that youth with asthma have been found to have a greater prevalence of anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms.79 A 2016 cross-sectional study found that children with atopic diseases had more emotional, hyperactive, and conduct problems than those without asthma.10 Children with asthma at age 5 have been found to have higher odds of both externalizing and internalizing disorders.11

On the other hand, a higher prevalence of asthma has also been found in persons with mental health problems: a 2011 cross-sectional study of adults found an increased prevalence of asthma among individuals with a history of ADHD.12 Other studies have found strong associations between anxiety and asthma, with higher prevalence and worse symptoms of asthma seen in patients with anxiety.9,13 Furthermore, a large multi-country study (World Mental Health Initiative), found, based on retrospective declarations, that mental health disorders such as panic disorder, specific phobias, and even certain eating and substance abuse disorders have strong associations with subsequent asthma in adult populations.14

A mental health disorder and asthma association has been documented in children as well: a 2014 study of Korean schoolchildren aged 7–8 found that those with ADHD had a higher relative risk of asthma compared to those with no ADHD.15 A 2011 cross-sectional study of schoolchildren aged 5–12 found a statistically significant association between the presence of behavior problems and asthma symptoms.16

It seems then that asthma and mental health have some associations. The direction of the association has been documented in populations suffering from asthma and in mental health-disordered persons; however, since studies were mostly transversal the directionality has been challenging to assess. Recently, a 2019 cohort study found that adults with depression had a higher risk of subsequent asthma development and that those with asthma had a higher risk of subsequent depression development: suggesting a bidirectional relationship.17

Biological and psychosomatic explanations for the relationship between mental health disorders and asthma exist. Acute stress has been associated with increased airway inflammation, shown by exhaled nitrous oxide and decreased lung function.18,19 Mental health disorders, especially among young people who may not fully understand their situation, could easily precipitate bouts of acute stress that could then lead to asthmatic symptoms and asthma. Inflammatory cytokines namely, IL-1, IL-4, and IL-6, and TNF-a, which are also important mediators of asthma pathogenesis, have been associated with internalizing disorders such as depression.20 Furthermore, Neuropeptide Y has been shown to be associated with stress, particularly among those with anxiety.21 The biological mechanism shows the overlap between asthma and mental health. While the high comorbidity rate between both disorders is well documented, the exact nature of the biological mechanisms and the need for a full model that ties both disorders should be areas of new research. Behavior problems may also play a role. Individuals with mental health disorders may be less likely to comply with or seek asthma treatment. This would increase the prevalence and severity of asthma and asthma-like symptoms among patients, especially children. Studies have shown that youth suffering from mental health disorders oftentimes have much worse asthma than their peers without mental health disorder, and that psychological factors play a big role in explaining the variance in asthma severity.22

It should also be noted that most studies on mental health and asthma status have occurred predominantly in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Strong differences in asthma prevalence exist across countries and geographic boundaries as the global trend is increasing.3,7 Furthermore, these studies mostly focused on adult populations whereas asthma concerns children as well and could be very detrimental to their development.

To fit that gap, in the mid1990s, an International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) was launched by using a standardized protocol to measure the prevalence of asthma symptoms in large numbers of countries from all the regions of the world. This allowed drawing children from a sample of schools, mostly urban centers within a country, and to examine the correlations between the prevalence of asthma symptoms reported by ISAAC and national mortality asthma and hospital admission rates obtained from national registries and found a significant positive association.2 Regrettably, this study did not measure mental health problems associated with asthma in children.

The present study aimed then to complete a large international study, in seven European countries, by using, for children 6–12-year-old, ISAAC indicators together with a unique exhaustive set of mental health measures from three informants: the children themselves, the parents and the teachers. This was rendered possible thanks to the School Children Mental Health Europe (SCMHE)23 which covered large populations of school children using well-established mental health measures: (1) the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)24 for parents and teachers, validated in many languages [20] and allowing a diagnostic prediction through parents/teachers combinations, including their declarations on child impairments23,25 (2) the Dominic-Interactive: a video self-administered instrument26 validated in these seven languages.27

Such a study spanning very diverse countries aimed to provide better insight into the relationship between a large scope of young child mental health problems, from different perspectives, and asthma status indicators. Indeed, teachers’ and parents’ evaluations are expected to differ28 as well as parents’ and children's.29 Since such young child evaluation instruments mostly rely on external informants, the study will be able to contrast children's own perceptions of their mental health, and adults’ (teacher and parents combined) evaluations and their respective associations with asthma. It will also enable the study of child external problems, internalizing disorders as well as their co-occurrence, and asthma, controlling for socio-demographics and countries.

Our study objectives are then (1) to determine the prevalence of asthma symptomatology along ISAAC indicators among school children 6 to 12 in seven countries, (2) to determine some associations between asthma indicators and socio- demographic factors (3) to determine the association between child asthma indicators and mental health problems, internalizing and externalizing, based on child, versus parent teacher combined reports.

Based on previous research we expect important differences in child asthma indicators across countries as diverse as Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey due to their environment. We also expect children with mental health problems to have a higher odds ratio for asthma; for internalizing as well as externalizing disorders, including after controlling for most socio-demographic predictors including countries. We expect the self-evaluated child's mental health to be more associated with asthma than the parent/teacher combined mental health indicator since children self-reports for internalizing problems have been proven as superior to parents and teachers evaluation.30

MethodsSampleThe School Children Mental Health Europe (SCMHE) study is a cross-sectional survey of European school children. These schoolchildren range from 6–12 years old. The sample included data collected in 2010 in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey. Details for country-specific collections can be found in previous literature.26 The sample for the survey was designated as approximately 50 randomly selected schools chosen per country with 48 randomly selected children each except for Germany where a greater number of schools was approached (150 schools per region) due to the difficulty experienced by the research staff in securing approval from schools, as schools were reluctant to participate in research involving young children.

Combining school participation rates and child participation rates yielded the following participation rates per country: 4.1% in Germany, 24.5% in the Netherlands, 41.7% in Turkey, 49.4% in Lithuania, 54.6% in Italy, 58.8% in Bulgaria, 64.5% in Romania. 8135 children completed a self-administered mental health evaluation; parent and teacher mental health evaluations were available for 6031. Only individuals who completed usable information on asthma and both the self-reports and SDQ parent or teachers were included in our sample, among them 5721 schoolchildren.

MeasuresParent's questionnaireThe parents completed a questionnaire on demographic characteristics of the household including their family link to the child, place of living (rural area/village, small/medium town, large town), and both parents’ education levels that will be combined to obtain the highest level reached by one of the parents, the parent's psychological distress as measured by the SF-36 MH5 (Mental Health 5 items) subscale31 and the SDQ. 88,97% of the respondents were the mothers or stepmothers, 11,03% were fathers or stepfathers. Teachers completed the SDQ plus some measures on the child's school competencies.

Asthma status was determined by parent questionnaire according to the guidelines of ISAAC (International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood).32 Respondents were asked:” Has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past?”; then for those who positively answered, the question focused on the last 12 months. Questions followed on the severity of symptoms such as the number of attacks of wheezing, sleep disturbance due to wheezing, and limits to speech. In order to recapture those who may have not identified asthma, questions were added such as “Has your child ever had asthma” along with other questions pertaining to asthma symptoms: “In the last 12 months, has your child's chest sounded wheezy during or after exercise” and “In the last 12 months, has your child had a dry cough at night, apart from a cough associated with a cold or chest infection.” A question regarding wheezing after exercise has been found in Australasian surveys to identify some children who themselves or their parents/guardians are unaware of or deny their asthma status.29 Nocturnal coughing is widely considered a proxy for asthma status.29 Following the seminal Anderson's paper,2 we built two indicators: (1) 12-month episode of wheezing or whistling in the chest and (2) an indicator of severe asthma based on their proposal using a combination of the three severity indicators previously mentioned. ISSAC being an international project, its indicators translations have been done according to scientific standards.33

Child mental health problemsChild self-reports on mental health came from the Dominic Interactive.30 This program uses a combination of images and scenarios that progresses through the 91 situations of the male-Dominic or female-Dominique character. As the child goes through the DI they answer if they feel or have felt like their respective character in a yes/no fashion.

The DI uses the DSM-V criteria to represent the 7 common child mental health disorders. Specific phobias, separation anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). depression/dysthymia disorder, which could be pooled as “internalizing disorders”; oppositional/defiance disorder, conduct disorder, ADHD, which could be pooled as “externalizing disorders”. The 91 situations use a combination of audio and visual cues to help children identify complex emotions into a situation they can understand. Previous studies have shown that the DI is internally consistent as well as having application cross-country borders.27,34

Parent and teacher reports on child mental health were drawn from the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).35 The instruments ask parents and teacher 25 questions regarding the child's behavior over the past six months, and is divided into 5 sections: emotional, hyperactivity/inattention, conduct, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviors. An impact measure was used to assess mental health problem impacts on the child's daily life. The author proposed a predictive diagnostic algorithm that combines parent and teacher's subscales results as well as impairment. This was applied to our sample to produce four indicators: emotional, ADHD, conduct problems or any of these. Both the SDQ and DI were completed in the native language of their respective country and the instruments were validated in each of the languages.36,37

Statistical analysisThe prevalence of each of ISAAC indicators was compared for each country by chi-square. The two indicators were built: the 12-month wheezing or whistling in the chest (WWC) and the 12-month severe asthma (SA): either 4 attacks or above, one or more nights of sleep disturbance per week or speech ever limited. Logistic regressions for these two indicators were used to determine the OR of each socio-demographic potential predictor on these indicators including parental mental health distress; for country comparison “grand means” were built, that is a numerical average of a group of average. Then OR between each child's self-report mental health problems for 12 months WWC and SA were estimated, unadjusted and adjusted for the main sociodemographic indicators using logistic regressions. The same approach applied to the four predictive diagnoses from parent/teacher SDQ combinations.

All analyses were done in STATA 17 BE.1 Results are reported at the p = 0.01 level instead of 0.05 to take into account the number of comparisons, p lower than 0.05 but higher than 0.01 are mentioned for complete information.

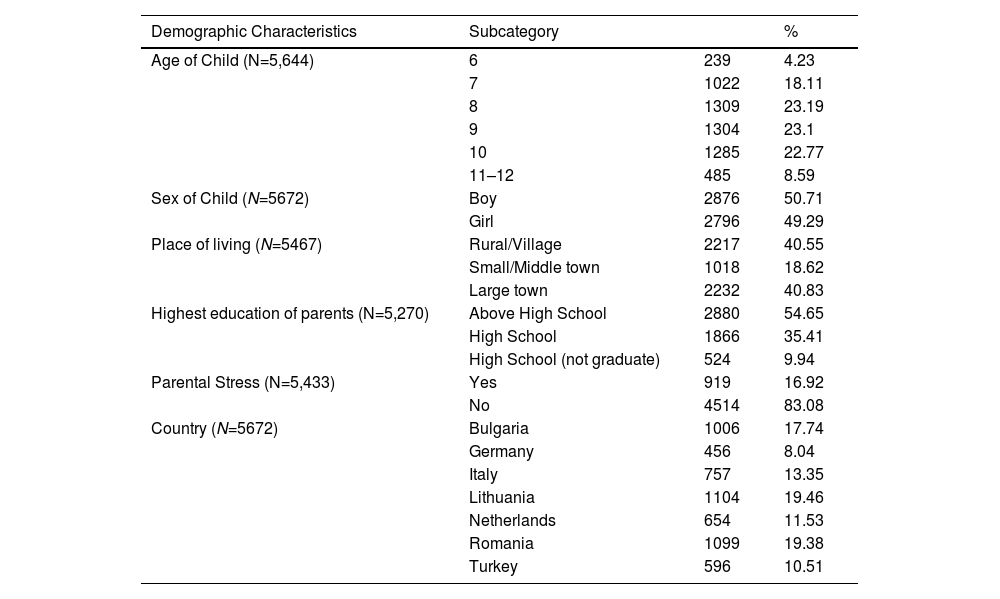

ResultsDemographic characteristics of the SCMHE sampleA total of 5721 children were used in the complete analysis. Table 1 describes some of the key demographic characteristics of the SCMHE survey. Mean age was 8.71 (8.67–8.74 95% CI) A roughly even ratio of girls to boys was observed, 40,55% of respondents lived in an area classified as rural while 40,83% lived in a large town. The parental level of education is high: 9.94% only did not complete high school and 54.65% had some higher than high school level of education.

Demographic characteristics of the SCMHE sample.

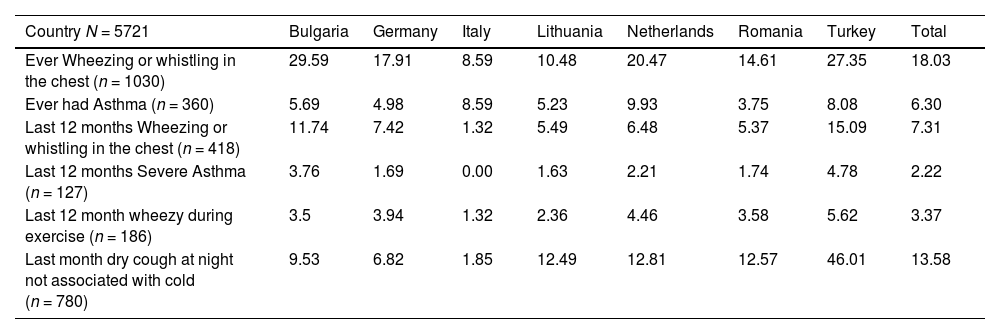

Table 2 shows the prevalence of each of the ISAAC indicators in the seven countries. High variations among European countries were present: for example, 12-month WWC ranged from a low 1.32% in Italy to a high 15.09% in Turkey, followed by Bulgaria 11.74%; each indicator differed at p < .00001; severe asthma was not found in Italy and except for Turkey and Bulgaria, was found to be rare in the other countries.

Asthma ISAAC indicators by country.

Each intercountry difference Chi(2) <.00001.

Table 3 shows the univariate ORs for possible confounders between asthma and mental health disorders. Age and gender of the child were found to have statistically significant relationships for WWC, gender only for severe asthma. To live in a large town was very much associated with both indicators, as was either parent not having completed high school. Parental distress has an OR = 1.66 for WWC only. Using comparisons to the grand mean, Italy was found to have a low OR =0.20 for WWC and Turkey and Bulgaria respectively had OR 2,71 and 2.00. Similar trends appeared for severe asthma and mental health disorders based on country except that Romania has OR=1.58 whereas Italy has no such case.

Univariate Analysis of Covariates on WWC and severe asthma.

Bold Values are those with p values under 0.01.

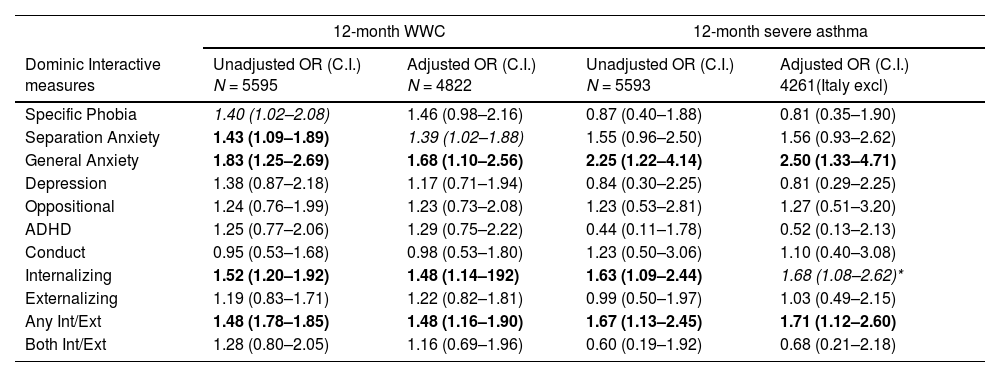

Table 4 shows the associations between each of the Dominic Interactive self-reported child mental health problems and asthma indicators: WWC and SA. Univariate analysis showed that internalizing disorders were significantly associated with WWC; mainly SAD and GAD but not any of the externalizing problems. Controlling for child's sex, age, parental education and psychological distress, place of residence and country, these associations remained to a lower extent: for SAD OR=1.39 was significant at p = 0.035 and for GAD at p = 0.015 OR=1.68. Results on SA paralleled the WWC: GAD was even more associated OR=2.50 for adjusted OR; internalizing disorders OR remained significant although to a lower extent once adjusted OR=1.68 p = 0.022.

Child reported mental health problems and 12-month WWC and severe asthma.

Adjusted for Child ‘s Age, sex, type of setting, parental education, parental stress, country. Bold Values are those with p values under 0.01, Italic p = 0.035, *= 0.022.

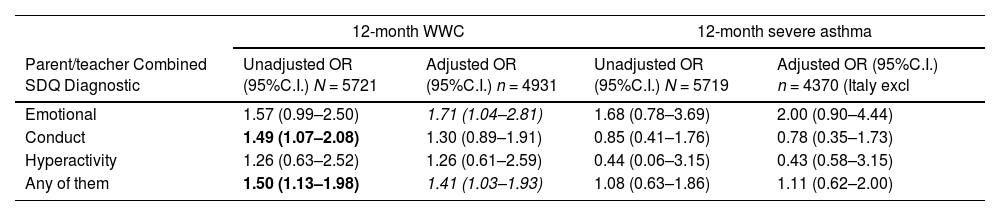

Results using the predictive diagnoses on WWC showed different results than child DI: emotional problems were not significant unadjusted but once adjusted were significant OR=1.71 p = 0.034; contrary to the child DI, conduct problems had a significant OR=1.49 (p = 0.018) with WWC; the presence of “any of these diagnoses” was associated with WWC unadjusted and adjusted: OR=1.41 (p = 0.034). None of the predictive diagnoses showed significant associations with severe asthma, adjusted or not (Table 5).

Parent/Teacher combined mental health problems and odds of 12 month WWC and severe Asthma.

Adjusted for age, sex, residence setting, higher parent education, parental stress, country. Bold Values are those with p values under 0.01; Italic p = 0.034.

Our findings could be compared to the ISAAC-reported findings on European asthma prevalence using the same indicators. For children aged 6-7 the estimated 12 months WWC parent reported was 11.6% having increased by 0.13% per year.38 However, the intercountry variation was very large and only a few rates are available on this age range: we have found a rate for a similar indicator for Lithuania (1999): 6.6%; Germany (1994): 8.4%2 quite close to our findings in these countries.

The highest rate of asthma indicators was observed in our sample in Turkey. Previous literature has found the prevalence of wheezing as high as 53% in young children, and asthma-like symptom prevalence in adults has been noted at 34%.37,39 A 2015 study found a significant association between the number of asthma cases and the level of urban air pollution in Turkey.40 Pollution in Turkey has been a major public health concern in recent decades due in part to the country's rapid industrialization, and numerous studies have examined the relationship between air pollution and adverse population health in cities.41,42,43 A 2002 study of asthma rates of schoolchildren 7–11 in Central and Eastern Europe found the 12-month wheezing rates: 14.5% in Bulgaria and 6.8% in Romania44 higher than our 2010 rates respectively: 11,74% and 5.35%; the lifetime such rates being also lower: for Bulgaria 40.8% versus 29,59% and for Romania 16.6% versus 14.6%. This decrease corresponded to a decreasing trend in pollution in Europe between these periods. In our study, as in the Leonardi one, to have “asthma” was much lower and not parallel to the WCC: for Bulgaria 2.8% versus 5.69% in Romania 8.3% versus 3.75%, which fits with the difference in diagnostic and medical practices across countries. For Italy it should be reminded that the data were collected in Sardinia, where pollution is being described as lower than Italy and asthma less frequent.45

Our findings on internalizing disorders from the child self-report are consistent with previous findings on the association of internalizing disorders and asthma.11 Particularly, our association found between generalized anxiety disorder and asthma agrees with some of the previous literature. Most recently, a 2018 study of adult population in the US found that asthma was associated with greater risk of mood disorders and general anxiety disorders.46 While internalizing disorders were found to have an association with our asthma indicators, depression on its own was not shown to have a statistically significant positive relationship. Depression is rare in very young populations, so it is possible that our 6–11 sample is too young for depression to develop.

The predictive diagnostic approach combining parents/ teachers and impairment supports the relationship between internalizing disorders (labelled emotional in the SDQ) and asthma once adjusted, similarly to what was found with the child self-reported mental health. An association with conduct problems was found but did not hold after adjustments. We did not find any association with ADHD, contrary to what was reported in a previous 2014 study of Korean schoolchildren.15

Children self-evaluated mental health seemed to be more associated with asthma than parents/teachers combined evaluation, especially for severe asthma and general anxiety disorder, whereas this did not appear in the parent/ teacher's combination. Low to moderate agreement was found regarding parent-child mental health problems, consistent with previous literature:29 children are more aware of their internalizing problems than their parents and teachers, whereas parents and teachers are more aware of their externalizing problems, which are not well perceived by young children but disturb family's and school's life. Since asthma is more associated with internalizing problems, the child evaluation is more related than parent's or teachers’ evaluations.

Our study has some strengths. Our study attempts to alleviate the issues of only focusing on urban populations or adolescents by including a wide range of schoolchildren across Europe and Turkey with a young age range of 6–12. Furthermore, our analyzed sample from the SCMHE databank of 5602 children represents one of the largest sample sizes in studying mental health disorders and child asthma. Our study also helps address the issues of the determination of asthma prevalence by using not only diagnosed asthma reports but proxies of asthma such as constant night coughing and wheezing after exercise as proxies for asthma status. Using the DI also provides an accurate way of employing a self-report of mental problems among a very young age group. Including both self-reports of mental health from the children and parental/teacher reports allows for a more holistic analysis of youth populations regarding their mental status.

Limitations of our study are those typical of a cross-sectional survey-based study. As a cross-sectional study causality cannot be determined and neither can the temporality of asthma and mental health relationship. It's possible that asthma more often precedes the development of a mental health disorder and that the mental health disorder exacerbates the asthma condition and symptoms. Other issues for our study are asthma status reporting is subject to recall bias among participants; another limitation of our study is the method of asthma status determination. Asthma is also not a simple disorder to characterize and exists on a spectrum with a wide range of severity and symptoms. As such how asthma status is determined can oftentimes under or overestimate the true asthma prevalence. In our study, asthma status is done through a combination of two indicators: a 12-month episode of “Wheezing or whistling in the chest, “and a “severe” asthma based on the presence of one in three severity criteria. To assess asthma status more accurately in future studies, a combination of medical history, self-report, examination, and respiratory ability test should occur. As in any survey there were some non-participants that could differ from the participants; however, controlling for demographic factors allowed to decrease some demographic biases but the relationship to mental health as well as asthma could affect the participation in both directions. Some countries have lower participation rates than other specially Germany; however, this is due to difficulties to obtain school authorities participation rather than individual refusals. Mental health is evaluated by SDQ which has been largely used across the world, but it is not a clinical evaluation, even by using the predictive algorithm. Finally, a p-value of less than 0.01 was used to take into account the number of tests. However, it is possible that some tests may be significant by chance.

Mental health disorders and asthma exhibit broad comorbidities, and both disorders can start early in a person's life course with long-lasting consequences. While the exact nature of the relationship between mental health disorders and asthma remains unknown, it appears that individuals with certain mental health disorders are at higher odds of asthma and asthma-like symptoms. It appears that certain mental health disorders in youth internalizing disorders, pose as a risk factor for asthma. Further exploration of the associations between mental health disorders and asthma among youth is needed.

EthicsThe procedure was approved by an ethics committee of each country. All seven countries had the support of their respective governments, including the minister of education and health. Ethical support was received by the necessary authorities for each country. In Germany and Turkey where, ethical committees operate differently than the other countries, different procedures were used that were approved. In addition, each country provided authorizations from school authorities. In Bulgaria: The Deputy Minister of Education, Youth and Science of the Republic of Bulgaria; in Germany approval was obtained through landers: (a) Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (b) State school authority, Luneburg (c) Ministry of Education and Culture of Schleswig–Holstein country; in Lithuania: the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania; in the Netherlands: the Commission of Faculty Ethical Behavior Research; in Romania the Bucharest School Inspectorate General Municipal, in Turkey: the Istanbul—Directorate of National Education; and in Italy: the ethical committee of the Association of European Mediterranean University. Parents have to provide written signed authorization, otherwise children were excluded; in addition, children consent was obtained verbally. Data were anonymized.

This study was funded by the European Union, DG SANCO Grant Number 2006336 (V. Kovess-Masfety).