This paper tests the behavioral firm theory by examining exogenous economic shocks to explore whether switching to an innovative strategy is always reasonable. A quasi-experimental design – difference-in-difference – has been run on 1000 companies for 11 years to explore the consequences of strategic shifts towards innovations. It is found that companies that introduced innovations do not have any substantial differences from those that kept the ‘status quo’. However, those few companies that decided to follow a proactive strategy during crisis by introducing new R&D projects outperform their rivals in the medium-term. A nonlinear relation between the decision to switch to an innovative strategy and related performance suggests that returns to scale exist. Only those cases of innovative shifts that enable the growth of more than 50% in intangible assets on average and more than 30% in a recession appear to be successful and lead to higher performance for companies.

Different strategies of similar companies in the same market can be observed. Some companies invest in innovating; meanwhile, others just follow innovative leaders. Insch and Steensma (2006), quoting Maidique, point out that some companies will be first movers, while other firms will be followers. This behavioral heterogeneity was addressed by Hommes & Zeppini (2014), who investigate evolutionary switching between innovative and imitating strategies using a set of conceptual solutions. As a result, they demonstrate that costly innovations are not always reasonable. In line with Greve (2003), this study is framed within the behavioral theory of innovations, bringing development and decision-making ideas together. This theory proposes a prediction of innovative behavior driven mainly by performance and slack. A crucial distinction of this behavioral perspective may be formulated as examining the incentives and causes that underpin firms’ decisions. One of the probable extensions of this idea refers to the phenomenon when firms change their behavior to an innovative or, alternatively, a more conservative path. In the interpretation of the behavioral theory, this means that mainly internal drivers, like those related to a firm’s degree of satisfaction with its current performance, may drive companies either to change their strategy or to keep the ‘status quo’. This study focuses on these particular cases and attempts to contribute to a better understanding of the way companies take strategic decisions when it comes to innovations.

The theory of behavioral innovations has been addressed rather often in the literature, even though sometimes this specific term is not mentioned. Jenkins (2014) explores how the innovative cycle is organized in his qualitative study on the role of collective beliefs. It has been revealed in this paper that based on their subjective perception of competences, managers decide to introduce innovations, or to get a ‘first-mover advantage.’ Moreover, the evolution of companies’ strategic behavior is affected by exogenous shocks that might make them shift from an innovative to an imitative approach, or vice versa. This phenomenon has been previously analyzed by Cincera et al. (2010), who studied the use of R&D in a crisis in the framework of the European Project. Their main finding refers to the ambiguity of innovative strategy. Cincera et al. (2010) place stress on an unacceptable level of financial and operational risks brought by R&D expenditures, especially under crisis conditions. One recent discussion published by Gilbert (2014) debunked the myth ‘Innovate or perish’ and came up with the idea of a ‘first-mover advantage’ based on disruptive innovations that are becoming more widespread and usurping current competition. One of the most influential researchers in this crisis-innovation problem, Daniele Archibugi, published several papers that discuss companies’ change in R&D investment in response to the global crisis of 2008−2009. Archibugi et al. (2013a), Archibugi et al. (2013b), and Archibugi and Filippetti (2013) consider it reasonable to adopt different patterns of corporate strategic behavior for business under different types of conditions.

Notably, academic interest in the financial crisis at a macro-level and innovative strategies has turned to the discussion of different implications for innovative strategy. Meanwhile, issues related to the dynamic nature of corporate strategy and the continuum of alternatives considered by companies are still understudied both conceptually and empirically.

This research sheds some light on drivers that can lead companies to be more intensive in innovations. For that, it addresses two drivers of strategic switching – some related to internal factors, and others bound with external conditions. We hypothesize based on behavioral firm theory and empirical findings from mergers and acquisitions by Ruth et al. (2013) and a firm-specific response discovered by Bamiatzi et al. (2016) that previous unsatisfactory performance could lead a company to change its strategy. The other driver is the factors that all economic agents face. The financial crisis is taken as the most apparent external driver that must be considered when strategic decisions are undertaken (Archibugi & Filippetti, 2013).

Furthermore, it appears essential to explore which outcomes strategic changes might bring. Our study focuses only on technological or organizational innovations that are bound with R&D expenses and the value of the intangible assets of companies (Hommes & Zeppini, 2014; Tidd et al., 2005). That means that only innovations that resulted in any kind of intellectual property rights are considered hereafter. The maintenance of the current level of innovativeness is identified as a ‘status quo’ strategy. Meanwhile, any increase in R&D that resulted in an accumulation of intangible assets is considered in this study as a shift toward a more innovative strategy. This paper calls this phenomenon ‘switching to an innovative strategy’. The study does not differentiate between incremental and radical innovations, as the degree of radicalism from ongoing R&D projects cannot be determined unless this outcome is obtained and implemented. Some studies measure innovation or innovative performance as sales from new products as a percentage of total sales, because this measure would reflect the success of new products (Fernández-Olmos & Ramírez-Alesón, 2017). The problem is that this information only is available from surveys. We have tried to find an objective measure for an innovative strategy.

The present study explores real patterns of companies’ strategic behavior for innovations by setting the following research questions, driven from the behavioral firm theory (Greve, 2003) and empirical findings on crisis-driven innovative strategy (Archibugi et al., 2013a, 2013b; Cincera et al., 2010):

- •

Do companies switch to an innovative strategy under turbulent conditions when the performance of the ‘status quo’ strategy is high?

This question is addressed to test the behavioral theory of the firm by putting forward a hypothesis that if a company performs better than its rivals, there are no evident incentives to exert effort for a strategic shift.

- •

Do companies switch in stable or turbulent economic conditions? If a crisis induces strategic shifts, does it drive companies to better performance?

This question relates to whether external drivers make companies innovate more, expecting better results in post-crisis recovery.

To answer the questions raised in this study, it identifies two models and test them empirically on data from 1000 Russian listed companies. The first model focuses on factors that affect the probability that a company switches to an innovative strategy; the second defines whether switching to an innovative strategy drives companies to better performance. The paper works with a panel-data structure that covers a period from 2004 to 2014 and enables us to examine the crisis period of 2008−2009.

The next section of the paper gives an overview of the academic discussion on innovation, with an emphasis placed on crisis conditions. It allows us to get proper model identification. The following sections introduce the quasi-experimental research design; present the data and the econometric strategy, employing a difference-in-difference technique. The results are tested for robustness, interpreted and discussed, taking into account the limitations of unavoidable endogeneity that makes estimates somewhat confined from setting causal effects.

2Should all companies innovate?This question has been discussed in heated debates since the Schumpeterian model of business cycles appeared in the 1940s. In classical economics and business literature, innovations were considered by default the most critical driver of economic growth. Erdil Şahin (2015) concludes that there is a positive and statistically significant impact of R&D expenditures on economic growth. It had been forecasted that the world economy should reach a bifurcation point of innovation in the early 2000s (Hallegatte et al., 2008; Hirooka, 2006), and after that, a critical amount of disruptive novelties should have changed our society.

Samra et al. (2018) assert that a crisis can motivate companies to increase performance despite its threatening nature. In that sense, innovation measured as R&D intensity has been considered as an advantage for the survival of companies. The idea of ‘innovate or perish’ questioned here has been popular since Eekels (1984). However, evidence on the relationship between innovation and firm survival is varied and often conflicting (Ugur et al., 2016). Moreover, these authors found an inverted U-shape relationship between R&D intensity and the survival of companies. It is expected here also to find that kind of relationship.

Archibugi (2017) raised the idea that despite the enormous technological changes that can be seen now, especially those driven by ICTs, many technologies used in daily life and production are still very conventional. Moreover, many businesses have gravitated to conservative strategies thus far. Vocoli (2014) draws examples of big well-known companies out of the information-technological sector that might be seen as non-innovative. This phenomenon has been proved empirically in some recent papers that examine innovative behavior and its consequences. Shakina & Barajas (2015) discovered that in value-creation, European companies with a conservative strategic profile predominately outperform European companies with an innovative profile, and that innovative companies eventually overinvest in R&D and that this fact can be perceived negatively by majority of investors. However, it would be fair to note that the best innovative businesses in Europe are substantially better off than any other business with a different strategy and that ‘good’ innovations enable sustainable competitive advantages for those companies. That makes us conjecture that decisions on investment in innovation require very precise deliberation and coherence in understanding the actions of key business stakeholders: managers, shareholders and even competitors. Jenkins (2014) captures the importance of an imitation threat that might make companies stop doing innovations.

In an attempt to study the rational behavior of companies, Shakina et al. (2017) developed a theoretical model and found that companies decide to switch to an intangible-intensive strategy under certain conditions and affirm that there is an optimal investment level where the maximum value is reached. Among the most critical factors, the ‘status quo’ performance plays a pivotal role when the decision to change strategy is accurately undertaken. Apart from internal drivers, the expectation of positive and negative shocks to profit is crucial. Furthermore, as Shakina et al. (2017) affirm, when an expected negative shock is substantial, other things being equal, companies should postpone switching to a higher intangible-intensive strategy. When it comes to a significant negative shock – economic crises or just a downturn – innovations attract even more attention.

3How probable is it that companies shift their strategic behavior towards innovations in crises?In answering this question, scholars can be divided into two main groups. Archibugi, Filippetti, and Frenz (2013a) analyze economic crises and innovation by studying whether destruction prevails over accumulation. A UK Community Innovation Survey shows a majority of companies cut R&D investment during the recent economic crisis. Meanwhile, a small cohort of innovative, fast-growing firms were even more likely to intensify their innovativeness, making efforts to introduce new products and services (Archibugi et al., 2013a). Archibugi (2017) raised a problem of the causal ambiguity of crises and innovative corporate behavior. He initiated a discussion about how even one of the central classics of ‘techno-economic paradigms’– Schumpeter – discussed the slowdown of economic growth and even crises that can be caused by innovations. Still, at the same time, he affirmed that firms take advantage of crises to introduce disruptive innovations since discontinuity is needed to change technologies significantly.

For our study, the second direction of causality is of greater importance. This issue is related to many empirical studies that have appeared in recent years following the 2008−2009 crisis. As one could expect, more financially dependent companies with higher capital-intensity appear to be affected more negatively. Other scholars have sought to find evidence of innovation-driven recovery and economic growth on the meso-level by looking into regional inequality. Kaufmann (2015) unexpectedly failed to find a strong correlation between innovativeness and employment growth in crisis. A partial explanation of this finding was given by Bamiatzi et al. (2016). Leaning on the well-known resource-based theory, these authors assumed and later proved that the idiosyncratic effects of companies become ‘stronger under adversity’. This fact makes all other effects, like those related to industry, region substantially weaker.

As can be seen, empirical findings and their interpretation are heterogeneous. Still, without delving into the details of each of those papers, some outlines can be drawn. First of all, companies tend to take advantage of turbulent conditions by seeking to reshape the market landscape.

Secondly, innovative leaders do not always maintain an aggressive investment policy under economic adversity, which is demonstrated by a relatively more modest financial policy and more rigorous risk management demanded by their investors. Fernández-Olmos and Ramírez-Alesón (2017) found that a weak point in the macro-economic cycle negatively influences innovation performance.

Thirdly, more innovative strategies both in crises and in prosperity do not always result in better performance. Firm-specific factors beyond their strategic, innovative initiatives make outcomes of these investments substantially more unpredictable in adverse conditions.

All the facts, as mentioned earlier, led us to study whether for-profit shifts in strategic behavior towards innovations may bring companies to expected success and under which conditions this has a negative effect on performance. The next section introduces the strategy for model identification together with the attempt to estimate it on data of more than 1000 Russian large corporations that are representative of the economy of that country.

4Switching to an innovative strategy: model identification and dataIn answering the research question of this study, a model of switching to an innovative strategy has to be identified. Despite the apparent simplicity of what an innovative strategy looks like, it is a challenging task, nonetheless. As a rule, companies do not explicitly state that they intend to change their strategic behavior. The only way to capture this switching is to rely on markers that could be seen as pronounced traits of the new strategy – in our case, innovative strategy. Lutz (2014) states that economic theory implies that R&D efforts lead to the development of intangible assets and that these assets contribute to an increase in the overall profits of the firm. Taking that as a base, this paper has considered that R&D expenditures followed by an increase in the value of intangible assets disclosed in corporate reports is a sign of switching to an innovative strategy. However, even this common phenomenon, with an increase in R&D and the associated capitalization of intellectual property, does not always represent evidence of switching to an innovative strategy. The level of growth of intangible assets also matters. A gradual increase in intangible assets maybe just a sign of the evolutionary development of the firm.

Meanwhile, a reasonably significant surge might demonstrate a switch to innovativeness. Still, it is difficult to find any rigorous validation of the sufficient level of these changes. For that, it is assumed that both continuous and discrete cases have to be considered and empirically studied. Thus, this paper proposed the following scheme of identification:

- •

The 1st condition: a company had R&D expenditures at least during the two previous years.

- •

The 2nd condition:

- -

a company has an increase in intangible assets in the current year

- -

a company has at least a 25% increase in intangible assets in the current year

- -

a company has at least a 50% increase in intangible assets in the current year

- -

a company has at least a 75% increase in intangible assets in the current year

- -

a company has at least a 100% increase in intangible assets in the current year

Jointly these two conditions identify cases that are interpreted as a switch to an innovative strategy. This operationalization certainly appears to be one of the most arguable issues in our strategy, since increases in intangible assets may be driven by other factors unrelated with successful R&D investments, such as brand re-evaluation, software adaptation, and many others. Meanwhile, considering companies have no evident incentives to register significant increases of intangible assets under the taxation regime in Russia, it is assumed that the vast majority of revealed cases are due to a technological innovation switch. Technological innovations due to the successful accomplishment of R&D is the most apparent reason to register a significant increase of intangibles assets on the balance sheet.

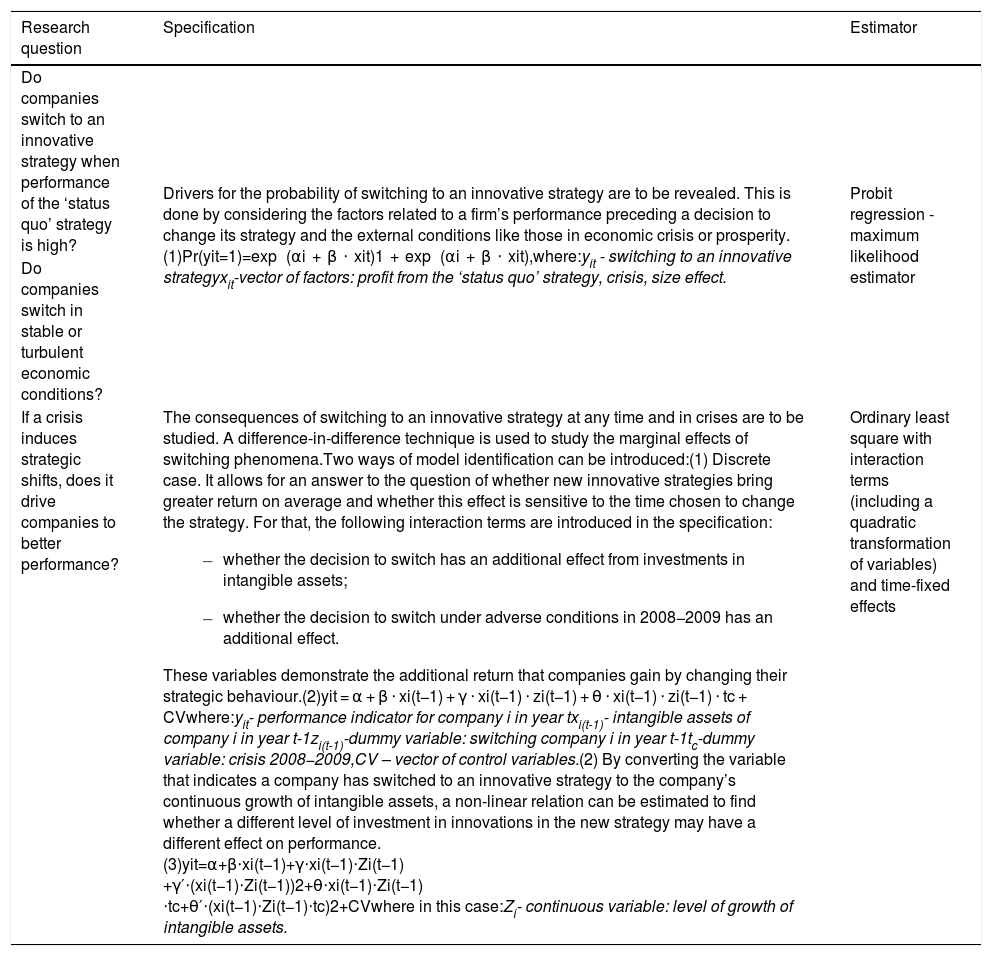

The following steps of our investigation refer to the econometric strategy that enables us to answer the research questions. Table 1 shows them and explains the specification and the estimators used.

Operationalization of the research questions and econometric strategy.

| Research question | Specification | Estimator |

|---|---|---|

| Do companies switch to an innovative strategy when performance of the ‘status quo’ strategy is high? | Drivers for the probability of switching to an innovative strategy are to be revealed. This is done by considering the factors related to a firm’s performance preceding a decision to change its strategy and the external conditions like those in economic crisis or prosperity.(1)Pr(yit=1)=exp (αi + β ⋅ xit)1 + exp (αi + β ⋅ xit),where:yit - switching to an innovative strategyxit-vector of factors: profit from the ‘status quo’ strategy, crisis, size effect. | Probit regression - maximum likelihood estimator |

| Do companies switch in stable or turbulent economic conditions? | ||

| If a crisis induces strategic shifts, does it drive companies to better performance? | The consequences of switching to an innovative strategy at any time and in crises are to be studied. A difference-in-difference technique is used to study the marginal effects of switching phenomena.Two ways of model identification can be introduced:(1) Discrete case. It allows for an answer to the question of whether new innovative strategies bring greater return on average and whether this effect is sensitive to the time chosen to change the strategy. For that, the following interaction terms are introduced in the specification:

| Ordinary least square with interaction terms (including a quadratic transformation of variables) and time-fixed effects |

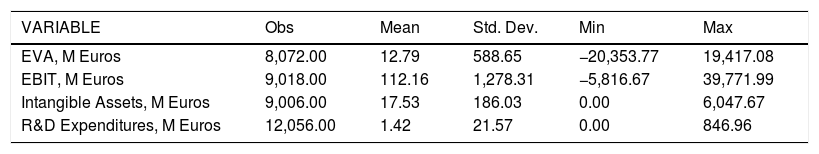

The analysis has been carried out on a sample with more than 1000 listed Russian companies observed from 2004 to 2014. This setting comprises companies from all industries, and has a panel structure that enables a dynamic exploration of the variables of interest. Notably, measures of performance are introduced in the data by a set of indicators, including operational profit (Earnings before Interest and Taxes -EBIT) and Economic Value Added (EVA -measured as the excess of operational profit above opportunity costs, taken as the cost of capital employed). For our study, inputs are represented by two indicators: R&D expenditures and the book value of intangible assets. Furthermore, the vector of control variables includes industry, year, and a company's size (measured by the book value of its total assets). A more detailed picture of the dataset can be found using the statistical description shown in Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of proxy indicators of innovation intensity and performance for Russian companies in 2004-2014.

| VARIABLE | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA, M Euros | 8,072.00 | 12.79 | 588.65 | −20,353.77 | 19,417.08 |

| EBIT, M Euros | 9,018.00 | 112.16 | 1,278.31 | −5,816.67 | 39,771.99 |

| Intangible Assets, M Euros | 9,006.00 | 17.53 | 186.03 | 0.00 | 6,047.67 |

| R&D Expenditures, M Euros | 12,056.00 | 1.42 | 21.57 | 0.00 | 846.96 |

As can be seen from the Table 2, the average level of both EVA and EBIT is positive for the companies in our analysis. Meanwhile, significant variation of these performance proxies testifies to the heterogeneity of companies and industries along with significant instability from 2004 to 2014. Looking at intangible assets, we conclude that their share in total book value is rather low for Russian companies, as could be expected. It is a consequence of the low intensity of innovative activities for most of these companies. Moreover, this is confirmed by the small number of companies that introduce innovations. For companies in our setting, it is not more than 5.7% on average for the whole period, with a peak of 12.1% in 2013. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) has been estimated, and its value is below 2 in all the cases.

It is worth noting that both performance indicators and innovation inputs are not evenly distributed across industries. See Appendix A in Supplementary Material where Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of EVA and EBIT from the six sectors as grouped in the dataset once outliers were excluded.

The density of the median level of EVA is significantly higher in Finance benchmarked to the sample average. This means that those companies are more homogeneous. However, that comes out naturally for this industry and the activities of firms in this sector. Furthermore, looking back to the descriptive statistics, the positive average value of EVA for the entire sample is due to a right-hand bias of the distributions for companies from Energy & Chemical, Services, and Finance. Companies from Construction & Real Estate, as well as Manufacturing, which comprise together about 57% of the whole sample, demonstrate a heavier left-hand tail.

An entirely different picture can be drawn for the EBIT cross-industry distribution (Figure 2 in Appendix A). All sectors demonstrate a right-hand-biased distribution, with the median value close to 0. This can be seen as natural for EBIT, since unlike EVA, this indicator reflects companies’ absolute performance and cannot be consistently negative for normally operating enterprises. Notably, financial companies are not more efficient for EBIT, in contrast with EVA. There is again a high number of low-marginal cases and a relatively small density of high-performing organizations. Meanwhile, the only evident highly performing sector is Energy & Chemistry, as could be expected for the Russian economy. The rest of the companies demonstrate a similar density of EBIT distribution, not considering outliers.

The descriptive overview of innovation assets and investments, measured in our study by the book value of intangible assets and R&D expenditures, respectively, shows that the majority of Russian listed companies are not intensive in both. The medium level of intangible assets in Construction & Real Estate, Finance and Trade is continuously zero, without any positive dynamics even for those companies that belong to the highest percentiles in our distribution. Notably, just in the epicenter of the global crisis in 2008−2009, the density of financial companies that are low-intensive in intangible assets substantially increased according to our data. Therefore, highly innovative ones are seen as outliers in our data. Looking dynamically at these findings, we may conclude that just a few financial institutions could afford this kind of investment during the crisis.

Nevertheless, there is a definite positive dynamic of intangible assets in industries such as Services, Energy & Chemistry and Manufacturing. The majority of those companies significantly raised their intangibles endowment, especially after the crisis years starting from 2010−11. For the Trade sector, this increase is observed only for 2014 and cannot be considered as a persistent trend (see Figure 3 in Appendix A).

There is still no consensus among experts over which years may be considered crisis periods. By leaning on the official statistics of Russian macroeconomic conditions, for the purpose of this study, 2009 is taken for the onset of the crisis, and the two following years are considered as a recession caused by this adverse impact (Ministry of Economic Development of Russia, 2009, 2010). These periods are marked by a significant downturn in the average values of performance indicators (EVA and EBIT). However, these periods are not conspicuous for the scale of companies’ innovative actions and generated intangible assets. The only exception is in the financial sector.

Only 5.7 % of companies in our sample that carry out R&D projects belong mainly to Energy & Chemical or Manufacturing. That could be foreseen even though the Trade sector demonstrated significant growth of R&D in 2014−15. If we zoom the scatter plots closer to the median value, positive trends of R&D are observed for Energy & Chemical and Trade. Meanwhile, other sectors, having several outliers, still do not introduce any positive dynamics in innovative projects related to R&D (see Figures 4a and 4b in Appendix A).

This preliminary statistical overview supports the supposition put forward in our study about companies that shift their strategic behavior to being more innovative. Evidently, a significant part of companies from Energy & Chemistry introduced more R&D projects after 2010. The same has been revealed for the manufacturing sector starting from 2013. Still, these changes are based on the average of different industries. Therefore, it might not be true for a particular company that may keep evolving but does not significantly shift its behavior.

5Drivers and the treatment effect of switching to an innovative strategyThis research examines switching phenomena to learn whether a new innovative strategy is reasonable, particularly in crises. The model that describes the process of the transformation of intangibles assets into corporate performance has been identified. This model allows for a difference-in-difference analysis, taking those companies that keep the ‘status quo’ as the control group and those that have switched to an innovative strategy as the treatment group. Following the research algorithm given in Table 1, an analysis of the dynamic behavior of listed Russian companies for 12 years starting from 2004 has been carried out.

For the first step, the markers of switching to innovative strategies are identified. As was assumed, R&D expenditures over two years, followed by an increase in the book value of intangible assets appear to point out a strategic shift. Moreover, five different thresholds of growth in intangible assets have been distinguished: any increase and 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% increase. Figure 5 in Appendix A shows the revealed switching of companies according to the stated levels. The minimum share of companies that have changed their strategic behavior was observed in 2009–2010, just after the crisis period of 2008−2009. That can be explained by a significantly low number of R&D projects initiated within the two years of the recession. The favorable conditions of the after-crisis recovery induced those investments and led to a substantial reshaping of the innovative landscape in 2011–2012. The following years have seen a correction of this abnormal surge.

An important finding is that in 2011, most of the companies that switched to innovations doubled their intangible assets. The convergence of all five curves demonstrates it before 2011. After that, trends have diverged. A quite similar picture can be seen for 2013. Nonetheless, the switching phenomena have been specified for a low share of companies. In other words, significantly innovative shifts were affordable for a limited number of companies. All other firms preferred not to have any change in their strategic behavior. The opposite result is shown for 2012. The majority of companies introduced R&D in the two preceding years, but the majority of them did not demonstrate substantial growth in intangible assets as a result. Notably, no companies switched to an innovative strategy according to our criteria in 2008 and 2009, and only a few of them have done so in 2010 and 2011, which can be considered the last years of the recession caused by the global economic crisis.

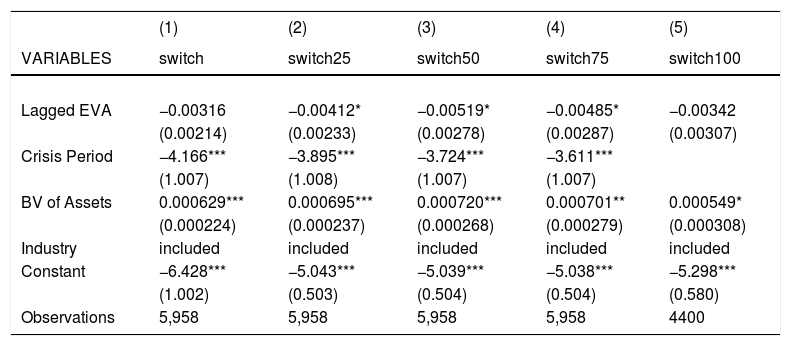

These results have been taken for the next step of the analysis. In answering the research questions stated in this study, we first are going to look for the drivers that make companies switch to an innovative strategy. The logit model identified to examine factors that affect the probability of changing the ‘status quo’ strategy allows for the investigation of internal and external factors (see Formula 1, Table 1). The research question was formulated to hypothesize whether high performance provided by the ‘status quo’ prevents companies from switching to an innovative strategy. The same assumption was implied when the crisis term was introduced in the model. Our conjecture refers to the following – firms choose not to take risky decisions by investing in R&D as a reasonable response to adverse conditions. Besides, it might be essential to examine which of these factors contributes more to the probability of a switch. The first set of models is estimated for performance measured by EVA (Table 3a), and the second one for EBIT (Table 3b). Notably, the models are specified according to the different thresholds of switching, as stated in the research design of this study.

Probability of switching at different levels (EVA as a metric of the performance).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | switch | switch25 | switch50 | switch75 | switch100 |

| Lagged EVA | −0.00316 | −0.00412* | −0.00519* | −0.00485* | −0.00342 |

| (0.00214) | (0.00233) | (0.00278) | (0.00287) | (0.00307) | |

| Crisis Period | −4.166*** | −3.895*** | −3.724*** | −3.611*** | |

| (1.007) | (1.008) | (1.007) | (1.007) | ||

| BV of Assets | 0.000629*** | 0.000695*** | 0.000720*** | 0.000701** | 0.000549* |

| (0.000224) | (0.000237) | (0.000268) | (0.000279) | (0.000308) | |

| Industry | included | included | included | included | included |

| Constant | −6.428*** | −5.043*** | −5.039*** | −5.038*** | −5.298*** |

| (1.002) | (0.503) | (0.504) | (0.504) | (0.580) | |

| Observations | 5,958 | 5,958 | 5,958 | 5,958 | 4400 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

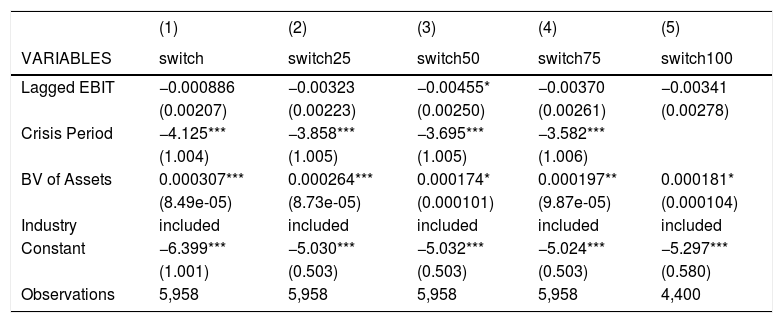

Probability of switching at different levels (EBIT as a metric of the previous performance).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | switch | switch25 | switch50 | switch75 | switch100 |

| Lagged EBIT | −0.000886 | −0.00323 | −0.00455* | −0.00370 | −0.00341 |

| (0.00207) | (0.00223) | (0.00250) | (0.00261) | (0.00278) | |

| Crisis Period | −4.125*** | −3.858*** | −3.695*** | −3.582*** | |

| (1.004) | (1.005) | (1.005) | (1.006) | ||

| BV of Assets | 0.000307*** | 0.000264*** | 0.000174* | 0.000197** | 0.000181* |

| (8.49e-05) | (8.73e-05) | (0.000101) | (9.87e-05) | (0.000104) | |

| Industry | included | included | included | included | included |

| Constant | −6.399*** | −5.030*** | −5.032*** | −5.024*** | −5.297*** |

| (1.001) | (0.503) | (0.503) | (0.503) | (0.580) | |

| Observations | 5,958 | 5,958 | 5,958 | 5,958 | 4,400 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

As can be observed, the crisis term is a significantly negative factor in the probability of changing strategic behavior. The marginal effect is between 7% to 11%, depending on the threshold taken for marker of switching to an innovative strategy. That means that years of adverse conditions have seen fewer cases of strategic shifts to innovations. At the same time, the performance of the ‘status quo’ seems to be significant for a substantial change only at the threshold of more than 50%. Still, the corresponding marginal effects are rather low – less than 0.08%. In answering the research questions whether companies switch to an innovative strategy when the performance of the ‘status quo’ strategy is high and whether they choose stable economic conditions to change their strategy, it can be suggested that the second factor is more important. That implies that previous performance does not matter as much, and only external conditions drive companies to strategic changes towards innovations. This condition allows us to run the next step of the analysis based on a difference-in-difference technique, since no significant difference in performance among those companies that change their strategic behavior and those that keep the ‘status-quo’ is observed in our setting. This randomization is of particular importance when the results of treatment will be interpreted.

Thus, the response of companies to adverse conditions does not mean that switching in the period of a crisis necessarily has desirable consequences. To examine this problem, we apply a quasi-experimental technique, namely, difference-in-difference analysis. As mentioned before, the most critical condition of this quasi-experiment is fulfilled. Any significant difference between the treatment and the control groups in their average performance before switching to a more innovative strategy is not established. The control group is represented by the majority of those companies that kept the ‘status quo’ during the entire period. The treatment group comprises companies that switched to an innovative strategy at any time and in recession years.

Given that perfect randomization is not possible, and one could suspect that better-performing companies are likely to have more chances to introduce innovations, we seek to control for all potential observed factors that might cause inequality between the treatment and control groups. The previous level of performance appears to be an essential control factor for the model. Furthermore, two models that are based on different performance metrics allow for a robustness check.

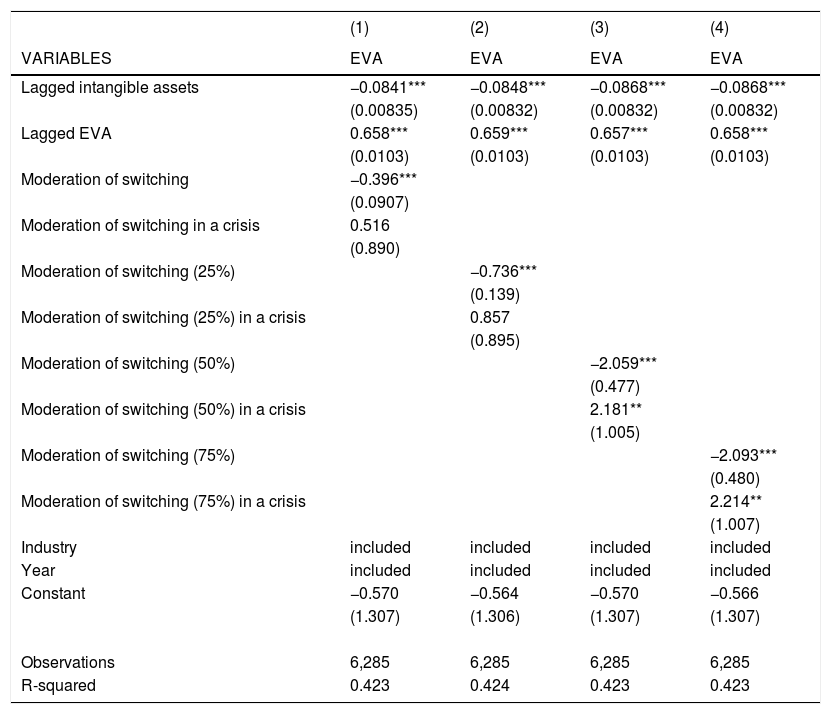

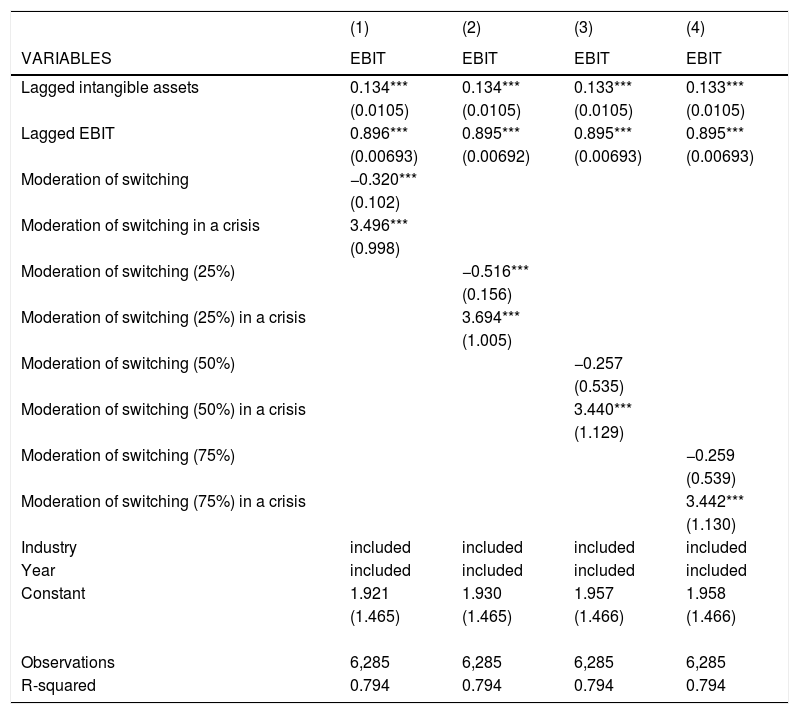

Tables 4a and 4b introduce the results of the model estimation based on Formula 2 (see Table 1). The moderation effect in these tables is considered an interaction term between lagged values of intangibles assets with dummy variables responsible for the identified cases of switching to innovative strategies under four levels of threshold. The moderation effect in crisis relates to the corresponded switching in the crisis years – 2009−2010. The four thresholds are examined in discrete cases. Looking back at our results of switching identification, we recall the finding that no companies doubled their intangible assets in the recession. For that reason, the last threshold for a 100% increase in intangible assets is omitted. The interaction terms with the lagged value of intangible assets outside and within crisis periods enables an analysis of moderation effects.

Difference-in-difference analysis of innovative strategies in crisis (performance measured by EVA).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | EVA | EVA | EVA | EVA |

| Lagged intangible assets | −0.0841*** | −0.0848*** | −0.0868*** | −0.0868*** |

| (0.00835) | (0.00832) | (0.00832) | (0.00832) | |

| Lagged EVA | 0.658*** | 0.659*** | 0.657*** | 0.658*** |

| (0.0103) | (0.0103) | (0.0103) | (0.0103) | |

| Moderation of switching | −0.396*** | |||

| (0.0907) | ||||

| Moderation of switching in a crisis | 0.516 | |||

| (0.890) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (25%) | −0.736*** | |||

| (0.139) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (25%) in a crisis | 0.857 | |||

| (0.895) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (50%) | −2.059*** | |||

| (0.477) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (50%) in a crisis | 2.181** | |||

| (1.005) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (75%) | −2.093*** | |||

| (0.480) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (75%) in a crisis | 2.214** | |||

| (1.007) | ||||

| Industry | included | included | included | included |

| Year | included | included | included | included |

| Constant | −0.570 | −0.564 | −0.570 | −0.566 |

| (1.307) | (1.306) | (1.307) | (1.307) | |

| Observations | 6,285 | 6,285 | 6,285 | 6,285 |

| R-squared | 0.423 | 0.424 | 0.423 | 0.423 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Difference-in-difference analysis of innovative strategies in crisis (performance measured by EBIT).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | EBIT | EBIT | EBIT | EBIT |

| Lagged intangible assets | 0.134*** | 0.134*** | 0.133*** | 0.133*** |

| (0.0105) | (0.0105) | (0.0105) | (0.0105) | |

| Lagged EBIT | 0.896*** | 0.895*** | 0.895*** | 0.895*** |

| (0.00693) | (0.00692) | (0.00693) | (0.00693) | |

| Moderation of switching | −0.320*** | |||

| (0.102) | ||||

| Moderation of switching in a crisis | 3.496*** | |||

| (0.998) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (25%) | −0.516*** | |||

| (0.156) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (25%) in a crisis | 3.694*** | |||

| (1.005) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (50%) | −0.257 | |||

| (0.535) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (50%) in a crisis | 3.440*** | |||

| (1.129) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (75%) | −0.259 | |||

| (0.539) | ||||

| Moderation of switching (75%) in a crisis | 3.442*** | |||

| (1.130) | ||||

| Industry | included | included | included | included |

| Year | included | included | included | included |

| Constant | 1.921 | 1.930 | 1.957 | 1.958 |

| (1.465) | (1.465) | (1.466) | (1.466) | |

| Observations | 6,285 | 6,285 | 6,285 | 6,285 |

| R-squared | 0.794 | 0.794 | 0.794 | 0.794 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The effect of switching, on average, is significant for all suggested thresholds. All the effects are negative. At the same time, it has been found that switching in a time of crisis demonstrates a statistically significant effect for EVA only after a 50% threshold increase in intangible assets. This effect is positive and compensating for the negative effect of switching in general. However, only if sufficient investments in innovations take place. For EBIT, this effect is demonstrated for all thresholds.

The results show a very curious phenomenon. The moderation effect of switching to an innovative strategy appears to be, on average, negative for all of the analyzed thresholds. Meanwhile, the same effect for switching within a crisis period is significantly positive and covers the overall effects for the treatment group. It has to be emphasized that the number of companies that introduced innovations during the crisis is rather low. Still, these firms demonstrate a higher level of innovation-driven performance.

For the model based on EVA as a metric of performance, the results have an even more vital contribution to test the hypothesis of our study. The results show a negative influence of intangible assets on economic profit on average, with even more negative moderation of shifting to an innovative strategy. At the same time, switching during adverse conditions brings a cumulative positive effect at all levels of the four discrete cases analyzed. Moreover, both models bring us to the conclusion that nonlinear relations are observed, and an optimal level of intangible assets growth can be established. The continuous case allows us to study this issue. These intermediate results made us extend the analysis to continuous cases by transforming a discrete variable responsible for switching strategy.

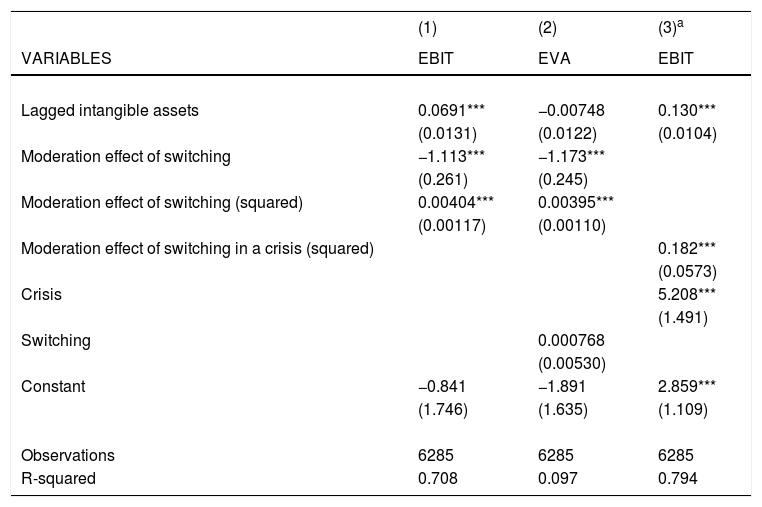

Table 5 shows the results of the estimations based on the Formula 3 (Table 1). The moderation effects for this stage of estimations are computed as an interaction between the lagged value of intangibles assets with the continuous variable of switching, which identifies any marginal increase in investments in innovations. The moderation effect in crisis corresponds to the crisis years – the interaction of the moderation effect between the value of intangibles assets, the continuous variable of switching, and dummy variables for crisis years.

Threshold in the switching strategy.

| (1) | (2) | (3)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | EBIT | EVA | EBIT |

| Lagged intangible assets | 0.0691*** | −0.00748 | 0.130*** |

| (0.0131) | (0.0122) | (0.0104) | |

| Moderation effect of switching | −1.113*** | −1.173*** | |

| (0.261) | (0.245) | ||

| Moderation effect of switching (squared) | 0.00404*** | 0.00395*** | |

| (0.00117) | (0.00110) | ||

| Moderation effect of switching in a crisis (squared) | 0.182*** | ||

| (0.0573) | |||

| Crisis | 5.208*** | ||

| (1.491) | |||

| Switching | 0.000768 | ||

| (0.00530) | |||

| Constant | −0.841 | −1.891 | 2.859*** |

| (1.746) | (1.635) | (1.109) | |

| Observations | 6285 | 6285 | 6285 |

| R-squared | 0.708 | 0.097 | 0.794 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

A U-shape relationship for switching to an innovative strategy is revealed for all periods and the crisis in particular. We have checked the extremum of the three polynomial and found out that the minimum sufficient investment level in intangibles over the initial value is observed around 23% for EVA and close to 32% for EBIT. Still, meanwhile, for the crisis period this extremum is shifted to 52%. The extremum is straightforward to interpret since all possible investment in innovations lower than the discovered threshold bring negative returns, which means that a change to innovative strategy is plausible and reasonable only if sufficient investments are made. That tells us that only a sufficient amount of newly introduced innovations can create success for companies. This finding seems to be reasonable and consistent with prior studies by Archibugi et al. (2013a), Bamiatzi et al. (2016), Cincera et al. (2010) and Hirooka (2006) discussed in our paper. Still, it goes a little further by demonstrating that crisis conditions are less demanding for the scale of innovations. And even not very significant innovative projects under low competitiveness might make companies better off. That can be explained by the fact that the threshold of innovation assets is lower for the crisis period. The analysis of the estimated function demonstrates that switching in a crisis is always reasonable for the given sample of Russian listed companies. These results are robust for both the discrete and the continuous cases investigated in our study.

6Conclusions and discussion of the results: is it worthwhile to innovate in a crisis?Our paper introduces a number of findings, mostly contributing to the understanding of firms’ strategicinnovative behavior under adverse conditions. Empirical results on the data of Russian listed companies certainly limit their extensive interpretation due to internal validity. However, some exciting insights should be considered as a contribution both to the literature and probably for policy consideration.

To answer the research question as stated here, a theoretical and methodological approach for innovative shifts in companies’ strategies has been introduced. An increase in intangible assets preceded by at least two years of R&D was regarded as a sign of switching to an innovative strategy. Apparently, not any increase can be considered as a switch. That was a reason to examine different thresholds that were deemed to be strategic shifts towards innovation. It has been explored whether past performance, according to behavioral firm theory, can be drivers of the decision to switch to a more innovative strategy if a firm’s level of satisfaction with its current performance is not sufficient. The testing of this hypothesis demonstrated that, under turbulent conditions, companies do not consider the level of their previous performance when a switch to an innovative strategy is undertaken. According to our empirical discovery, both low- and high-performing companies experience similar changes when changing their strategic behavior towards more innovative.

A difference-in-difference analysis of innovative strategy in a crisis has enabled some curious results. As it was expected, innovation-driven performance is not linear. By providing evidence that innovation-driven performance follows a U-shaped relationship, this paper shows that only substantial investments in innovations bring significantly higher performance in the medium-term. Importantly, a simple approximation of the functional form of the innovation-led production function provided us with a robust result that only more than a 50% increase in intangible assets for any sector and size of a company might bring sustainable positive returns. However, this increase is lower if the strategic shift is undertaken in a crisis. According to our findings, on average, crisis periods make the majority of companies abstain from innovations. Still, those firms that make proactive decisions by introducing innovations could outperform their ‘reactive’ rivals. In a crisis, this ‘sufficient’ increase is close to 30% of the initial value of intangible assets. Considering this and the fact that the threshold of innovation assets is lower for the crisis period, it can be concluded that not very significant innovative projects under low competitiveness might make companies better off. With that, we would like to debunk the myth about the unconditional necessity to innovate. This study demonstrates that the idea of '‘innovate or perish’ is not always true. This inference might be the most important contribution of this study.

However, let us outline some concomitant results, which we consider as additional contributions to our study. First, we have described the evolution of Russian companies regarding innovation from the period 2004 to 2014. As we have previously said, the influence of the crisis is strong when companies undertake strategic decisions to innovate. It has been revealed that in the case of Russian companies, the previous level of performance of the ‘status quo’ is significant for a substantial change at the threshold of only more than 50%. However, the marginal effects are rather low – less than 0.08%. With these findings, we can say that previous performance does not matter very much and that only external conditions drive companies to strategic changes related to innovations.

Secondly, our results demonstrate that the crisis term is not just a significantly negative factor in the probability of changing strategic behavior regarding innovation. As shown in our results, years of adverse conditions have seen fewer cases of strategic shifts to innovations. Furthermore, the crisis provided a substantially higher marginal effect of R&D-led performance.

Thirdly, for all of the analyzed levels, the moderation effect of switching to an innovative strategy appears to be on average negative. Simultaneously, the same effect for switching within a crisis period is significantly positive and covers the overall effects for the treatment group. Firms that introduced innovations during the crisis demonstrate a higher level of innovation-driven performance. The results obtained after this step bring us to the conclusion that nonlinear relations are observed, and an optimal level of growth in intangible assets can be established.

Finally, as was stated, a nonlinear relationship for switching to an innovative strategy has been examined. The revealed minimum level of the reasonable scale of innovation activities is in line with Archibugi et al. (2013a), Bamiatzi et al. (2016), Cincera et al. (2010), and Hirooka (2006).

Our results are robust to both the discrete and continuous cases investigated in our study as well as for both measures of performance (EBIT and EVA). The peculiarities of Russian companies can bias the study. However, some of the findings can be generalized. We assert that a minimum sufficient level of investment in innovation takes place. It has been theoretically modeled in the paper by Shakina et al. (2017) and empirically tested in this study. Admitting that the minimum sufficient level of investment may vary depending on an investigated market and a country, we, nevertheless, assume that for most of the possible cases, the minimum required can be found.

Moreover, considering that the Russian economy is in its fast-growing stage, which provides relatively higher marginal return from investments, we may suggest that for developed markets, the sufficient level of increase in innovations must be higher than the level established for Russian companies. Moreover, based on the findings of this paper, we can state that proactive, innovative policy in crisis is a reasonable response to adverse conditions. However, further developments of this methodological approach applied to firms in other countries would be of interest for checking the current results.

One implication of our findings for future research is that it is necessary to control for external conditions when considering firms’ decision to change their strategy in R&D intensity. This can be done on a comparative basis for cross-country analysis. Controlling for country-specific conditions is advisable because it can condition the effect of the findings set up so far.

In terms of policy and practice, our results point out that there may be an ‘optimal’ level of innovations for increasing the performance of companies. Moreover, the optimal level is likely to differ depending on external conditions, such as if there is a crisis occurring.

This study comprises research findings from the Project No. 18-18-00270 supported by the Russian Science Foundation. The authors want to thank Prof. Archibugi for his comments on the draft of the paper and to Jeff Downing for his help in proofreading the manuscript.