This study analyses the academic literature on the relationship between reputation and performance, exploring the different perspectives applied. It addresses a research gap by extending the scope of reputation management from a financial focus to a Triple Bottom Line approach incorporating social and environmental dimensions. A bibliometric analysis of records extracted from the Web of Science database was conducted using VOSviewer, followed by a thematic analysis with ATLAS.ti. Four main research domains were identified: (1) the financial domain, emphasizing financial performance and featuring prominent foundational works; (2) corporate social responsibility and sustainable practices, a well-established area focusing on social performance; (3) the emerging environmental domain; and (4) the strategic vision domain, which addresses microeconomic topics such as knowledge management and competitive advantage. This study summarizes key contributions, identifies future research directions, and establishes a tentative research agenda. Practitioners can use these insights to enhance reputation management processes, yielding financial, sustainability, and strategic benefits.

Corporate reputation is not an easy concept to define; in fact, the lack of an agreed definition is one of the major challenges limiting progress on this issue in the academic field (Walker, 2010; Dudot and Castellano, 2015; Khan & Digout, 2018; Calvo-Iriarte et al., 2023). The most frequently-cited definition was provided by Fombrun (1996: 165), who described it as “the perception of the company's past actions and future expectations that describe its overall attractiveness to its key stakeholders, when compared to its main rivals”. Given companies’ need to differentiate themselves in the current competitive climate, reputation emerges as a particularly valuable asset. Indeed, the Approaching the Future 2023 report released by Corporate Excellence, based on a survey of over 1300 CEOs across 43 countries, reveals that reputation management ranks third among the most significant management trends. Additionally, 46.4 % of the surveyed companies indicate that they are actively involved in managing their reputation.1

Another recent complementary view of corporate reputation identifies two dimensions: capability reputation, which centres on a firm's outcomes and involves creating value over time; and character reputation, which focuses on a firm's behaviour and encompasses stakeholders’ confidence in the firm and perceptions of its trustworthiness (Parker et al., 2019; Bundy et al., 2021). Taken as a whole, corporate reputation is an intangible asset that gives companies a distinct competitive advantage in the market for goods and services (Mahon, 2002; Helm, 2007a; Ghosh, 2017). It is thus considered a critical resource, using the terminology of the Resource-Based View of the firm (Boyd et al., 2010). Under Signalling Theory (Rindova et al., 2005), it can be viewed as a signal to the market of a “good reputation” among companies (Höflinger et al., 2018). Also, according to Stakeholder Theory, reputation is a way to manage relationships with stakeholders (Freeman, 1984; Wang & Berens, 2015).2 Signalling Theory and Stakeholder Theory seem to be the predominant approaches in the academic literature on this topic (Veh et al., 2019).

Just as there are multiple theoretical frameworks through which reputation can be explored, there are also numerous disciplines involved in the related research (Mahon, 2002; Chun, 2005). According to Mahon (2002), this is a subject that cuts across several disciplines; viewed individually, the perspectives from different disciplines do not offer a sense of the whole. Following this line of reasoning, multiple disciplines can be identified in this field of research: strategy scholars delve into the strategic and unique value of reputation (Chun, 2005; Rindova et al., 2005), viewing it as a source of competitive advantage (Hall, 1992); marketing scholars include it in studies of branding efforts (Ye et al., 2009); corporate communication scholars relate it to the firm's image construction processes (Ou et al., 2012); behavioural science and business scholars explore the socio-cognitive processes involved in the creation of reputation (Mishina et al., 2012); while accounting and finance scholars address the financial consequences of reputation, particularly its effect on financial performance (Hammond & Slocum, 1996; Mehra et al., 2006). Nevertheless, there is a need for more critical examination of how multidisciplinary perspectives on reputation-performance dynamics can contribute to a better understanding of the issue. Indeed, the unique value of reputation lies in its nature as a chain with multiple connections (Boyd et al., 2010).

For the reasons given above, this study adopts a multi-stakeholder perspective, recognizing that an organization can have multiple reputations depending on the specific stakeholder groups with which it interacts (Bundy et al., 2021). Therefore, corporate reputation is not a one-dimensional concept, but rather a collection of perceptions that vary across different audiences. This interpretation aligns with the work of Lange et al. (2011), who argue that reputations are audience-specific and context-dependent. Consequently, when it comes to defining reputation, we propose that an organization's reputation should be regarded as a strategic asset that not only attracts and retains investors, customers, and talent, but also enhances employee motivation, increases job satisfaction, and generates more favourable media coverage. However, when a company has multiple reputations, its various stakeholder groups may have conflicting perceptions. Managing these different reputations will require a strategic approach, such as the corporate diplomacy framework proposed by Henisz (2017), which emphasizes the importance of adapting communication and engagement strategies to the specific needs and expectations of each stakeholder group.

Despite exponential growth in the research on reputation, there are still significant gaps in the literature, particularly regarding the nature and extent of its relationship with financial performance, that is, from the outcomes perspective. While it is widely acknowledged that a good reputation is associated with various advantages, including a positive impact on company financial performance (Robert and Dowling, 2002; Boyd et al., 2010), the findings supporting this relationship are inconclusive (Lee and Roh, 2012; Saeidi et al., 2015), as we discuss further in Section II. In summary, while some papers assume that superior financial performance, defined as above-average profitability, enhances corporate reputation, the causation could run in the opposite direction, with other studies showing that having a better reputation than competitors can improve a company's performance. To reconcile these two lines of research findings, some studies propose a bidirectional relationship to better understand the potential interplay between these constructs. Other authors suggest including moderating and mediating variables in integrated models to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this complex relationship.

One reason often given for these apparently conflicting findings is that the measures of reputation and performance used to date are inherently unsuitable since they are overly complex and lack comparability. We agree with Bigus et al. (2024) and Veh et al. (2019) that measures of reputation do not align well with the definition of reputation due to its intangible and complex nature. This makes it difficult to interpret both theoretical and empirical studies of reputation. Measures of reputation generally depend on subjective appraisals by various stakeholder groups (Helm, 2007a). On the other hand, financial performance is generally used as a metric to the detriment of a more global vision of performance that includes non-financial elements (Castilla-Polo & Sánchez-Hernández, 2021), despite the fact that such a global vision can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of reputation for organizations. In this respect, the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework, which integrates economic, social, and environmental dimensions into performance analysis (Elkington, 1994), provides a global scheme of reference. Its connection to reputation has also been documented; for instance, Sridhar (2012) asserts that TBL reporting serves as a mechanism to enhance organizational credentials, improve status, and build reputation. Similarly, Abraham (2024) demonstrates a link between TBL performance and long-term corporate sustainability.

Given the inconclusive findings mentioned above, there is a critical need for a comprehensive overview of the reputation-performance relationship (RPR, hereinafter) and bibliometric methods serve as a useful tool to shed light on this area. Bibliometric methods are particularly valuable when researchers are dealing with large bodies of literature and have to keep pace with growing volumes of publications (Veh et al., 2019). Our objective is to summarize and synthesize the primary areas of interest in this research field, thereby contributing to the academic discourse on the RPR. To this end, the bibliometric analysis conducted here combines a descriptive approach with a co-citation analysis using VOSviewer to explore developments in the field up to 2023. In addition, the thematic analysis carried out with ATLAS.ti is aimed at validating the areas of interest that are identified and organizing the main findings into an overarching framework for a better understanding of this relationship. Our bibliometric and thematic analysis thus allows us to identify gaps in the literature and propose new avenues of research.

Drawing on the synthesized literature, this study provides an up-to-date picture of the state of the academic research on the connections between reputation and performance. The framework outlines both direct and indirect pathways by which reputation impacts performance outcomes and vice versa. By visually depicting these connections, our study offers a structured guide for comprehending the multifaceted nature of reputation-performance interactions in different contexts. It also extends the scope of reputation management research from finance (economic performance) to the TBL (incorporating social and environmental concerns in addition to legitimate economic goals), offering a more comprehensive understanding of this relationship.

To the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the first bibliometric and thematic analysis of the link between corporate reputation and performance in the academic literature. Some previous literature reviews have used this combination of techniques, but not in the field of reputation. Our study incorporates the latest publications in the field, identifying scientific clusters that allow us to draw conclusions on the dynamic and complex relationship under study, while the thematic analysis synthesizes all the previous evidence found. Previous qualitative literature reviews (Mahon, 2002; Chun, 2005) and systematic literature reviews have addressed reputation from a management perspective (Veh et al., 2019) or from a comparative management-accounting perspective (Bigus et al., 2024), but no previous literature reviews have considered the links between reputation and performance from a TBL perspective. To fill this gap in the literature, we attempt to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the main areas of interest in the research conducted to date on the relationship between reputation and performance?

RQ2: What are the primary arguments for and against the relationship between reputation and performance within the main areas of study?

RQ3: What future research directions should be pursued regarding the relationship between reputation and performance?

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework drawn from the literature, which underpins the research questions. Section 3 describes the bibliometric and thematic analyses conducted. Section 4 discusses our findings in reference to the three research questions proposed, establishes a tentative agenda for future research, and draws relevant managerial implications. We present the main conclusions as well as the implications and limitations of this study in Section 5.

2Antecedents: the controversial evidenceDefining corporate reputation is a difficult task due to its intangible nature (Bigus et al., 2024) and the fact that it is based on perceptions (Helm, 2007a; Pérez-Cornejo et al., 2022). Indeed, it is commonly described as the public recognition of a company that stems from its social approval (Zavyalova et al., 2016). Following Rindova et al. (2005), there are two dimensions in the conceptualization of corporate reputation: the first refers to stakeholders’ perceptions of an organization's quality; and the second refers to stakeholders’ impressions of the prominence of the organization. More recently, this conceptualization has been complemented by the distinction between capability reputation, which is focused on the generation of value over time, thus adopting an outcomes perspective; and character reputation, where reputation is viewed through the lens of the organization's behaviour, encompassing stakeholders’ confidence in it and perceptions of its trustworthiness (Mishina et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2019; Bundy et al., 2021).

Accordingly, in the pioneering paper by Helm (2007a), as well as more recent papers such as the one by Bundy et al. (2021), an important question is raised: does a company have one reputation or many reputations? Nevertheless, reputation is generally approached as a single construct, rather than as a combination of different stakeholders’ perspectives. Criticisms of the latter approach highlight the potential divergence in different stakeholders’ assessments of reputation (Harvey et al., 2017; Pollock et al., 2019; Chandler et al., 2020; Bundy et al., 2021). Indeed, external and internal reputations are not always aligned; some studies indicate that employees may perceive corporate reputation differently than external interest groups such as investors or customers. For instance, employees often prioritize aspects such as workplace culture, job security, and management practices, whereas external stakeholders may focus more on financial performance or corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Helm, 2007b). In short, reputation is a concept rooted in attitudes, with stakeholders playing a crucial role in shaping perceptions of the corporation (Veh et al., 2019; Sánchez-Iglesias et al., 2023).

Another trait that defines reputation, according to the influential papers of Walsh and Beatty (2007) and Gürel (2012), is its multidimensionality, which suggests that research on this area should adopt an interdisciplinary approach. In other words, reputation depends on different attributes that together determine the value of this intangible asset (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Fombrun & Van Riel, 2004; Flatt & Kowalczyk, 2008; Lai et al., 2010; Binderkrantz et al., 2023). The multidimensional nature of reputation explains why this asset cannot be adequately understood as a singular, uniform construct. Rather, reputation encompasses multiple aspects that are contingent on various factors, including the specific context, the nature of the relationships involved, and the criteria used to assess it. This multifaceted nature underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of reputation which accounts for the diverse social, cultural, and situational variables that shape how it is perceived and evaluated across different domains. According to Boyd et al. (2010), when it comes to enhancing corporate reputation, isolated efforts are not enough; firms must consider and address the intricate network of relationships involved.

In practice, the multidimensionality of corporate reputation justifies an interdisciplinary perspective (Walsh & Beatty, 2007; Gürel, 2012). Indeed, the participation of different disciplines in this field of research allows the incorporation of different schools of thought. Chun (2005) classifies three such schools that account for the key roles of different stakeholders; namely, the Evaluative School, the Impression Management School, and the Relational School (Table 1).

Schools of Thought on Reputation.

| SCHOOL | AUDIENCE | FOCUS | DISCIPLINES | KEY TOPICS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Evaluative School | Individual stakeholders: investors or executives. Reputation as an assessment of financial achievements. | Intangible assets and their relationship with business results | Finance/Accounting |

|

| The Impression Management School | Reputation as a global assessment, accounting for the views of different stakeholders. | View of the customer or end user of the product/service offered by the company | Management/ Marketing |

|

| The Relational School | Comparison between various stakeholders, both internal and external | Perception of the organization according to external vs internal stakeholders | Economics/Sociology/Public Relations |

|

Source: Own elaboration based on Chun (2005).

As can be seen in Table 1, the study of corporate reputation is a research field that incorporates a wide range of academic disciplines. Our study aligns with the schools proposed by Chun (2005), but also introduces the TBL framework; as we discuss later, the inclusion of the TBL is the main contribution of this paper.

Calvo-Iriarte et al. (2023) highlight the challenges of defining a concept like reputation: not only is it multidimensional, but it develops gradually, is not directly observable, and reflects the collective perception of a business. In fact, the time it takes to build a reputation (Walker, 2010) is a feature often mentioned in the literature (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006). Riel (2013) also discusses the dynamic nature of reputation; it is not a fixed value but evolves over time, and this volatility makes it more difficult for companies to manage. According to this last author, the dynamic nature of reputation means businesses must continuously adjust to stakeholder perceptions and react to both favourable and unfavourable events. These potential reputational changes require companies to actively manage their reputation, as any fluctuation can significantly affect their overall performance (Gatzert, 2015; Tetraul Sirsly and Lvina, 2019; Kim et al., 2021). Some papers on the topic have explored the idea of consistency in CSR (see Tetraul Sirsly and Lvina, 2019; Pérez-Cornejo et al., 2021) in order to explain how it helps to consolidate reputation; however, the analysis should be extended to cover consistency in reputation (Klewes, 2009). Certainly, the public recognition of a firm's consistent ability to deliver value helps reduce uncertainty, even among stakeholders without first-hand experience of the firm, while stakeholders are generally more willing to exchange resources with firms that have developed a strong reputation (Pfarrer et al., 2010).

A good reputation is a valuable intangible asset for firms, which is highly valued by markets and fosters trust and credibility among both customers (Ou et al., 2012; Islam et al., 2021; Winit et al., 2023) and investors (Ye et al., 2009). Additionally, reputable companies tend to attract exceptional talent, as they are viewed as desirable employers (Turban & Greening, 1997; Odriozola et al., 2018). Yet perhaps the most commonly cited benefit of reputation is that it leads to better financial performance (Robert and Dowling, 2002). According to Wu (2006), financial performance can be defined primarily through accounting-based measures, which use metrics such as revenue, profitability, cost efficiency, return on investment (ROI), and return on assets (ROA) to assess a company's ability to generate profits and value for stakeholders. All the advantages described above justify the academic and managerial interest in exploring the relationship between reputation and performance from an outcomes perspective.

Regarding the link between reputation and performance, there are conflicts in the literature concerning the evidence reported, the approaches used (Gatzert, 2015), the variables tested, and the significance and direction of the relationship. For example, while some previous studies suggest that reputable companies achieve better financial performance (Roberts & Dowling, 2002; Fanasch, 2019; Subramaniam et al., 2019), others are based on the idea that financial performance explains better corporate reputation (Cocis et al., 2021), since the market rewards companies that deliver good results. Other recent studies have proposed a two-way relationship between these constructs (Rose & Thomsen, 2004; Castilla-Polo & Sánchez-Hernández, 2021). However, there is no consensus in the literature on the relationship between these two variables (Waddock & Graves, 1997; Qiu et al., 2016). Various reasons for this divergence have been offered: reputation as either cause or effect, or a reciprocal relationship between the variables (Brammer & Pavelin, 2006); a lack of longitudinal studies, barring a few exceptions such as Hammond and Slocum (1996) and Castilla-Polo and Sánchez-Hernández (2021); the difficulty of studying intangible concepts (Fombrun, 1996); the effect of omitted variables (Saedi et al., 2015); problems measuring reputation (Lee and Roh, 2012); the non-financial effects of reputation (Berg et al., 2010); and the existence of an industry effect (Calvo-Iriarte et al., 2023). Ali et al. (2015) identify three other reasons that can explain this contradictory evidence: bias stemming from the country in which the studies are carried out; differences in the different stakeholders’ perceptual evaluations of this intangible construct; and the wide variety of possible measures of reputation. Finally, Parker et al. (2021) stress that it is important to account for the order of performance events and the intervals between them in analyses of corporate reputation. Overall, academic research on corporate reputation reveals a construct represented by multiple sub-dimensions, which is why its measurement is a particularly complex task for researchers. In addition, recent literature on reputation highlights that while reputation can provide numerous advantages, it also comes with costs. For instance, it can amplify the negative impact of adverse events, particularly for highly reputable companies. This perspective, often referred to as the "benefit and burden" of reputation, is explored in studies such as those by Zavyalova et al. (2016) and Parker et al. (2019), and can explain a potential inverse relationship between reputation and performance.

3Methodology3.1Search strategy and methodological designThe methodology used in this study involved a bibliometric analysis of data extracted from the Web of Science (WoS) database combined with a subsequent thematic analysis. Our search strategy centred on journals indexed in Social Sciences Citation Index, thus covering journals indexed in Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Citations in JCR are widely used in academia to assess the impact and quality of published research, simultaneously serving as a signal of reputation within the scholarly community (Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2020). In addition, the multidisciplinary coverage of WoS provides a comprehensive view of the relevant literature, which was particularly important for our study, given the aim of extending the scope of the RPR beyond finance to include different perspectives from the business field.

Fig. 1 summarizes the methodological design of this study, in line with previous related studies in the field of business and management (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2023; Atienza-Barba et al., 2024; Cordoba et al., 2024).

We accessed WoS in December 2023 using the search vector = ((reputation AND performance AND (relation* OR link* OR impact* OR nexus OR association OR network* OR union))) to capture the papers most closely focused on the RPR. The results of the initial search included 708 articles in English published between 1996 and 2023 (inclusive) and containing the search terms in its title or abstract. See Table 2.

Eligibility criteria.

| Link / Search Vector | ((reputation AND performance AND (relation* OR link* OR impact* OR nexus OR association OR network* OR union))) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SELECTION AND EXCLUSION PROCESS | https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/cdc5f870–3110–4688-ae92-d34c01c26d6a-012816d6a0/relevance/1 | Selection:Document Type: Article or Review Article (abstract or title)Database: Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI)Citation Topics Meso: 6.3 Management or 6.10 Economics | Original sample 708 |

| Selection:A random sample of one in every five papers was selected to verify whether the papers were thematically related to the topic under study | Intermediate sample 142 | ||

| https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/463c3de4–6d3f-447d-a13e-db8374409d21–012ad1dac7/relevance/1 | Selection:Document Type: Article (title)Database: Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI)Citation Topics Meso: 6.3 Management or 6.10 Economics | Final sample 42 | |

Source: Own elaboration.

The data collection started with these initial articles from JCR that met the eligibility criteria. Then, a “cleaning strategy” was applied through an exploratory analysis of a sample of these articles (Kristanto and Cao, 2023). A cleaning strategy in a literature review involves taking steps to ensure that the information gathered is relevant, coherent, and useful. The first step of this exploratory analysis was to randomly select and review one out of every five papers (142 papers) to assess their initial relevance to an analysis of the RPR.

The initial search returned a wide variety of topics not directly related to our research objective. For this reason, in setting the final search criteria, we chose to narrow down our focus to studies with titles specifically addressing the correlation between reputation and financial performance. This decision underscores the importance of titles in providing first impressions and succinct summaries of study content. Ensuring a clear alignment between the title and the issue explored throughout the study is critical for effective communication and an accurate understanding of the research conducted. Following this analysis, a total of 42 articles were deemed to meet all the eligibility criteria.

The records selected were reviewed by the research team during the months of January and February 2024 and a file with FAIR data from this research was created in the RUJA repository: https://ruja.ujaen.es/. The final stage of our methodological design was a co-occurrence analysis conducted using VOSviewer, and a thematic analysis of the primary research streams identified.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, a combination of two key methods was applied to our sample of papers: bibliometric and thematic analysis. Previous papers in related fields use a similar combination of methods. For example, Geppert and Lawrence (2009) conduct a content analysis of CEO letters as a proxy for reputation, while a combination of both methods is applied by Nagariya et al. (2020) to the subject of the service supply chain, by Prashar and Sunder (2020) to SMEs’ sustainable development, and more recently, by Madeira et al. (2023) to smart tourism.

On the one hand, bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive quantitative assessment of scientific output, offering a broad view of trends and patterns within a field (Öztürk et al., 2024). We opted for both a descriptive analysis and a co-citation analysis, which we describe further in the following sections. A co-citation analysis provides an evaluation of the relationships and connections between documents through shared citations. This method can be used to delve into the interconnections between different scholarly works, providing insights into how ideas and research themes evolve and interact over time.

On the other hand, thematic analysis (qualitative focus) offers the advantage of uncovering underlying themes and patterns within a sample of articles, and is more interpretative than content analysis (quantitative focus) (Vaismoradi & Snelgrove, 2019). Commonly used in the field of management research (e.g. Tate et al., 2010; Delgosha et al., 2022), the aim of thematic analysis is to understand the underlying meanings in selected texts, gaining contextual insights by examining content in its broader context to facilitate theme construction. While we used the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti to provide the frequency of codes, the focus of our thematic analysis was on visualizing the connections and relationships between codes and themes. The application of this method provided a deeper understanding of the data and allowed us to test the validity of our bibliometric analysis (Anlesinya & Dadzie, 2023).

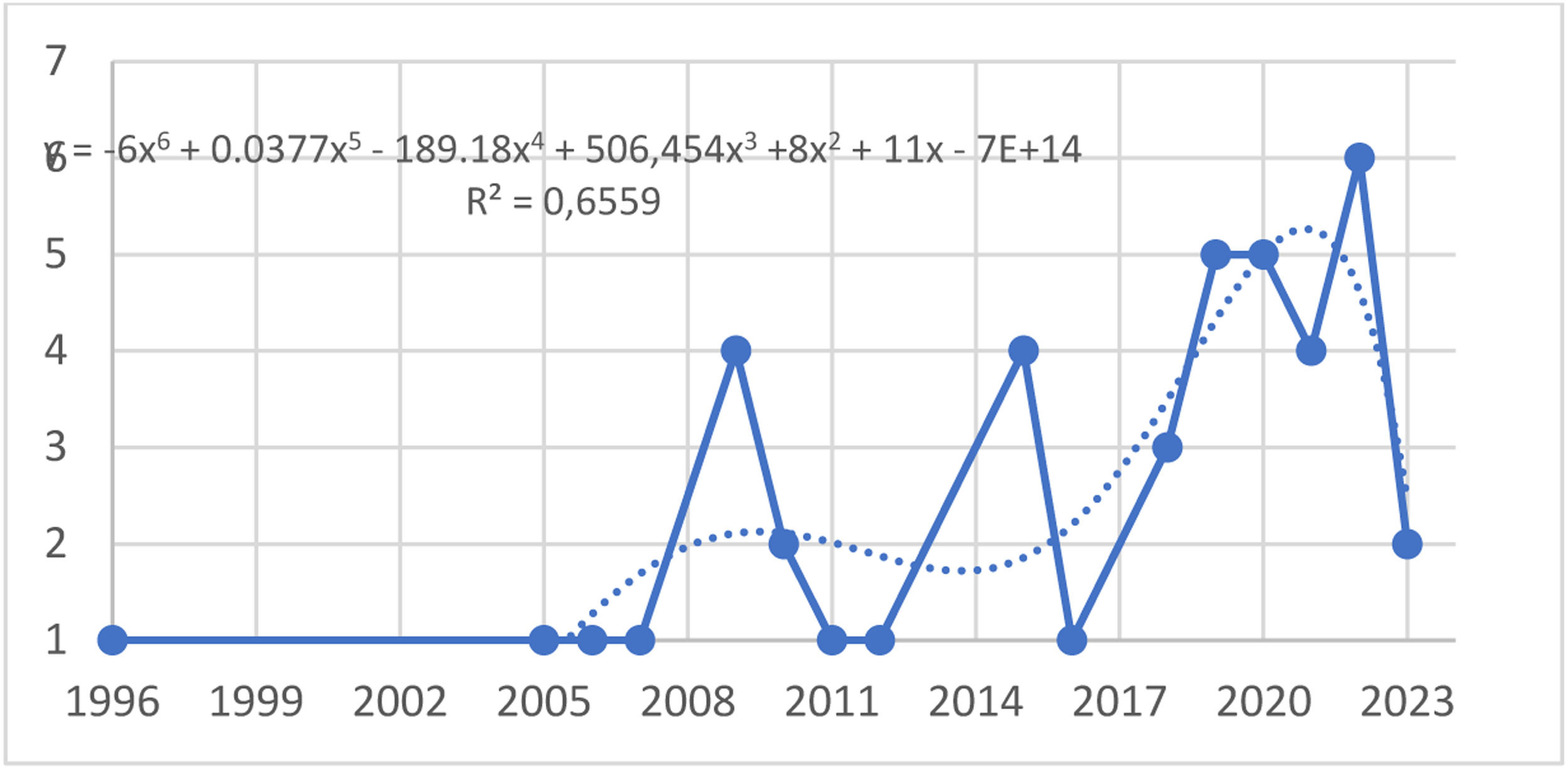

3.2Descriptive analysisIn this section, we outline the key characteristics of the current state of research on this area. The WoS data reveal the relative recency of the publications on this topic. Fig. 2 clearly shows the exponential growth in the number of studies on the RPR published between 2005 and 2022, with a single outlier publication in 1996. As can be seen in Fig. 2, a degree 6 polynomial function is the best fit with an R2 of 0.65. This implies that the increase in the publications on the RPR in WoS has not been linear, with ups and downs in different sub-periods.

This line of research started in 1996, when Hammond and Slocum published the first paper on this relationship: a longitudinal study comparing reputations and financial performance at two distinct points in time. The next publication identified is the paper by Neville et al. (2005), exploring how reputation influences the relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and financial performance. The most cited paper (299 citations) is by Mehra et al. (2006), who make a significant early contribution to this field by analysing how the social connections of group leaders affect both group performance and leader reputation. The volume of papers published annually has doubled since the middle of the period analysed and continues to increase to the present day. Although 2022 is the year with the highest number of publications, other peaks occur in 2009 and 2015 (4 papers each) and 2018 and 2019 (5 papers each) (Fig. 2), as we discuss later.

The journal that has most frequently published articles in this area is Business Strategy and the Environment, followed by International Journal of Hospitality Management (due to the frequent analysis of hotels as a business context within this area), Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Cleaner Production, Journal of Management, Management Decision, and Sustainability (Table 3). These journals can be grouped based on their thematic focus; for example, some centre on business strategy, management and ethics, while others focus on sustainability and environmental management. However, a total of 34 journals contribute to this area, indicating the extensive dissemination of research findings and reflecting the interdisciplinary approach to studying reputation.

Output by journal, author and country.

| PANEL A: OUTPUT BY JOURNAL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Publication Titles | Record Count | % (of 34 titles found) |

| BUSINESS STRATEGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT | 3 | 7.143 |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT | 2 | 4.762 |

| JOURNAL OF BUSINESS ETHICS | 2 | 4.762 |

| JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION | 2 | 4.762 |

| JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT | 2 | 4.762 |

| MANAGEMENT DECISION | 2 | 4.762 |

| SUSTAINABILITY | 2 | 4.762 |

| PANEL B: OUTPUT BY COUNTRY | ||

| Countries | Record Count | % (of 25 countries found) |

| USA | 13 | 30.952 |

| CHINA | 9 | 21.429 |

| SPAIN | 6 | 14.286 |

| UK | 4 | 9.524 |

| AUSTRALIA | 3 | 7.143 |

| GERMANY | 2 | 4.762 |

| INDIA | 2 | 4.762 |

| PAKISTAN | 2 | 4.762 |

| ROMANIA | 2 | 4.762 |

| PANEL C: OUTPUT BY AUTHOR | ||

| Authors | Record Count | % (of 123 authors found) |

| BERGH D.D. | 2 | 4.762 |

| BOYD B.K. | 2 | 4.762 |

| KETCHEN D.J. | 2 | 4.762 |

| SU C. | 2 | 4.762 |

Source: Own elaboration based on WoS data.

Another notable characteristic of the research is that it predominantly comes from the United States, China, and Spain, although authors from a total of 25 countries contribute to this field. Regarding citations, the most cited works as of February 25, 2024, are Mehra et al. (2006), Boyd et al. (2010), and Neville et al. (2005), with 299, 193, and 156 citations, respectively. Nonetheless, the maximum number of papers per author in this research area is 2, with 123 authors represented in the database.

3.3Co-citation analysis with VOSviewerAs noted above, all the articles meeting the eligibility criteria were analysed using VOSviewer software, which allowed us to produce the network visualization map and the density visualization map, grouping the keywords by means of a clustering algorithm. We created a map based on text data from the WoS bibliographic database using the “full counting” method. A threshold of at least 4 occurrences for a specific keyword was established. We then refined the sample by combining different forms of the search terms (e.g. CSR and corporate social responsibility, or FP and financial performance), resulting in a specific thesaurus, as in similar papers such as those by Kristanto and Cao (2023) and Dahbi et al. (2024). We also removed some general terms, such as data, methodology, paper, and limitations, among others.

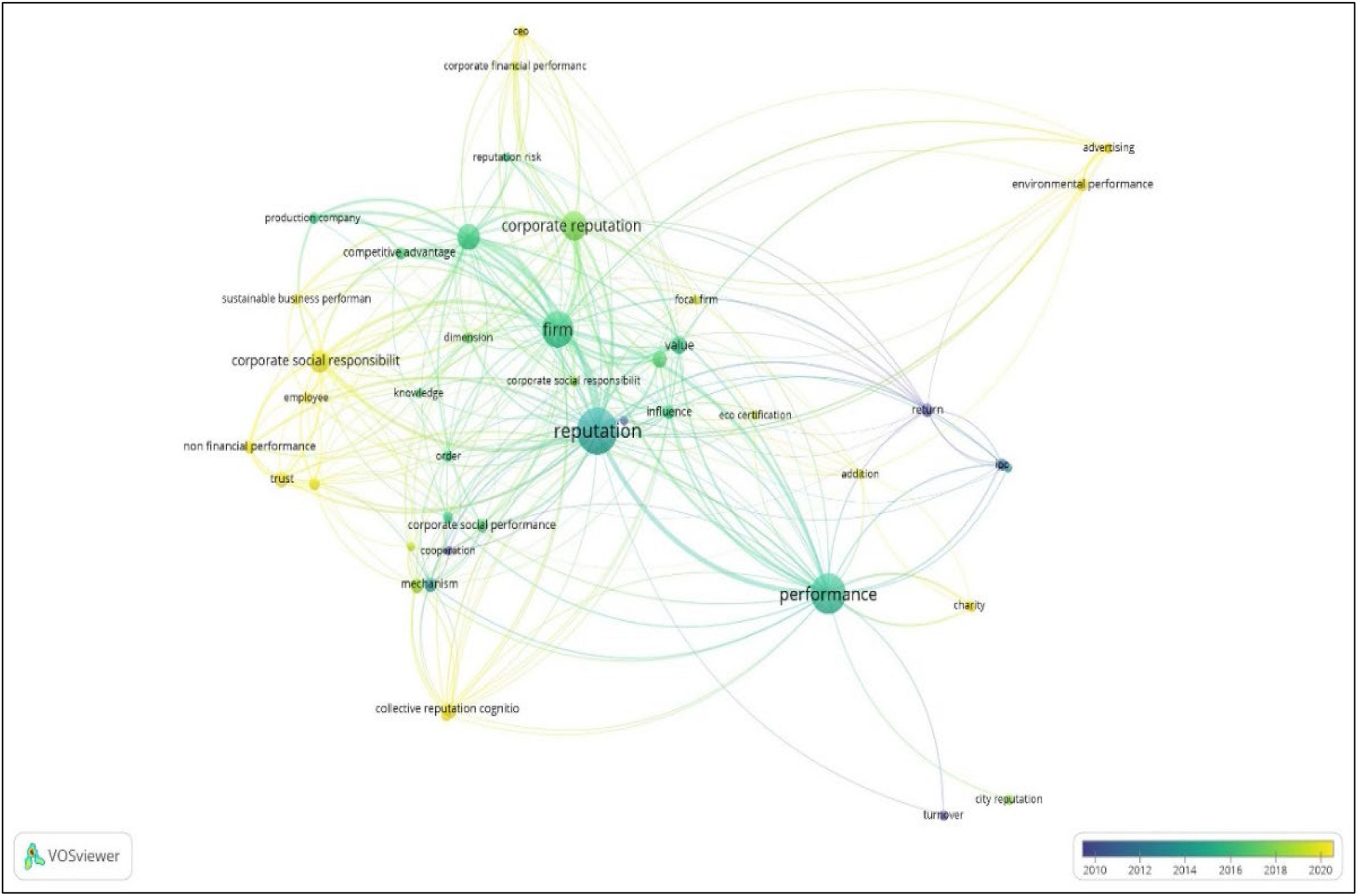

The main outputs of VOSviewer are shown in Fig. 3, network visualization; Fig. 4, overlay visualization; and Fig. 5, density visualization. The clusters identified, which are presented and explained in the following sections, allowed us to map the research landscape on the RPR.

Proximity analysis consists of the creation of clusters thought a resolution parameter generated by VOSviewer (Serrano et al., 2019). The network visualization shown in Fig. 3 displays the main keywords (nodes) and is called a keyword co-occurrence relation network. It is a weighted network because it depicts the keywords in different sizes and provides a distance-based visualization for the links between keywords. As we can see in Fig. 3, the word reputation in the middle of the network is the biggest, meaning that this word has the most weight in the analysis. Regarding the distance between nodes—for instance, the distance between reputation and environmental performance—a long distance between them indicates that they are not very closely related. However, eco-certification is relatively closer to reputation, indicating a connection between achieving ecological certifications and improving corporate reputation. The colour of each circle is determined by the cluster to which VOSviewer has assigned the keyword. For example, reputation and competitive advantage, in red, belong to the same cluster, while cooperation and corporate social performance, in green, belong to another cluster, as explained further below.

Reputation, performance, and firm are the three most common keywords in this field of research (large nodes), according to the density map. In addition, we found eight clusters reflecting the main areas of research interest: financial performance (the most prominent stream), social performance (a strong emergent stream), public and non-profit organizations, internal CSR, knowledge management, the role of reputable underwriters, environmental performance, and competitive advantage. We comment on these clusters in the next section addressing the thematic analysis, where we associate them with different fields of research.

The density visualization shown in Fig. 4 depicts the clusters found in the analysis. By default, VOSviewer assigns the keywords in a network to clusters. It is a complementary visualization of the relevance of each term since a cluster is a set of closely related keywords that can be identified by their density. Visualizing the density of clusters provides information about how clusters are distributed in the feature space. This map aids in the identification of dense clusters, which are areas with a high concentration of data points, as well as sparse clusters, where data points are more scattered. The keywords positioned in the centre of the map have more connections with the rest of the keywords. For example, the red cluster (financial issues) is in a more central area of the map than the blue cluster (environmental concerns), meaning that there are more connections between financial issues than environmental ones.

Fig. 5 is the overlay visualization, which is coloured differently. Here, the colour bar at the bottom right of this figure shows the time span, where blue is old, and yellow is new. For instance, collective reputation appears in yellow, which means it is a relatively new aspect of the topic under analysis compared to competitive advantages in greeny-blue. The figure clearly shows the difference between financial connections (dark colours/older) and sustainability connections (light colours/newer), a finding that opens the way for further research, as we discuss later.

3.3.2Mapping the literature: research streamsUsing VOSviewer, we mapped four research streams: finance; CSR and sustainable practices; environmental concerns; and strategy and competitive issues. We also linked these themes to the main supporting perspectives in an attempt to map the existing research onto the main areas of interest (RQ1) as well as the main arguments supporting this relationship (RQ2). Finally, the research streams identified allowed us to map the main trends and to establish a tentative agenda for future research, which is one of the proposed contributions of this study (RQ3).

3.3.2.1FinanceCluster 1 (red), called “financial performance”, has the highest weight (10 items) reflecting the importance of the financial perspective on this relationship. It is in a central location, indicating the strongest connection between its items and other clusters. This central positioning further underscores the vital role of the economic dimension within the TBL, with financial performance being a critical pillar of long-term corporate sustainability. In this context, economic outcomes are not standalone metrics but integral elements of performance that interact with the social and environmental dimensions of the TBL, calling for a holistic approach to achieving corporate success and sustainability. However, it is worth noting that this cluster includes the oldest papers in the field—such as those by Hammond and Slocum (1996) and Mehra et al. (2006)—as indicated by its dark colour in the overlay visualization. The most commonly occurring items, represented by the biggest nodes, include financial performance, risk and influence.

A common research objective among the papers in this cluster, which represents the financial perspective, is to corroborate the direction of the relationship between reputation and financial performance. Along these lines, Cocis et al. (2021) find that financial performance and equilibrium is an antecedent of investors’ perceptions of corporate reputation. In addition to corporate reputation, investors also value the reputation of the company's management, which impacts performance (Mehra et al., 2006). Similarly, CEO attributes have been incorporated into analyses of the causal relationship between corporate reputation, financial performance, and corporate sustainable growth (Mukherjee & Sen, 2022). Indeed, following Hammond and Slocum (1996), reputation can be defined as the stakeholders' perception of the quality of the firm's management. Another related line of literature focuses on reputational risk, a more recent stream in this cluster, which has been addressed by Gatzert (2015), among others. In other related papers, Baah et al. (2020, 2021) argue that organizational and regulatory pressures should be addressed as they trigger reputational improvements that impact financial performance and that can mitigate possible reputational risks.

Cluster 6, labelled “the role of reputable underwriters”, can also be included under a financial approach. It is strongly connected to financial performance (cluster 1), aligning with the economic dimension of the TBL. In the context of the TBL, financial performance is not only about profitability but also about the long-term viability of the firm, which can be influenced by the reputation of financial intermediaries such as underwriters. For instance, reputable underwriters can influence the success of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs).

This cluster contains older papers, as indicated by their colour in the overlay visualization map. Cluster 6 (grey) includes 5 items related to large listed corporations or IPOs. In the case of the latter, the question of how IPOs are influenced by underwriter reputation is analysed by Su and Bangassa (2011), who find that this type of reputation strongly affects the long-range performance of IPOs. Also, Su (2015) deals with the value of stock price performance against the background of the impact of investment bank reputation. Another common thread in this group of papers is the analysis of returns/abnormal returns instead of profitability as a measure of performance. Indeed, various variables related to stock market operations have been analysed in the studies belonging to this cluster.

3.3.2.2CSR and sustainable practices: a management approachCluster 2 (green), called “social performance”, is the second research stream identified, and is almost as relevant as cluster 1 (10 items). It is mainly dedicated to the analysis of the social performance of firms, but not necessarily corporations. It also focuses on CSR, which plays a crucial role—directly or indirectly—in the relationship under study. The authors in this cluster are more focused on overall performance, looking beyond financial performance, and reputation is linked to different items (nodes) such as communication, innovation, or cooperation. This cluster introduces TBL into the research on the RPR, specifically incorporating social concerns and demonstrating how social issues—such as ethical practices, communication strategies, and collaborative innovation—affect a firm's reputation. As a result, the papers in cluster 2 not only broaden the understanding of the reputation-performance link but also reinforce the focus on the TBL by highlighting the critical role of CSR in achieving long-term business success.

On the one hand, studies on CSR show its impact on financial performance (Neville et al., 2005), since CSR allows stakeholders to understand how their resources are allocated. Additionally, Singh and Mishra (2021) demonstrate how reputation moderates the CSR-organizational performance relationship, while González-Rodríguez et al. (2021) highlight the role of reputation as a mediator in this relationship. On the other hand, social performance is introduced by Wang and Berens (2015), who consider the effect of Carroll´s four types of corporate social performance on financial performance. They show that the company's economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic performance dimensions do not necessarily conflict with its value maximization objective, but the social performance effect is mediated by the company's reputation with public or financial stakeholders. Specifically focusing on the first of Carroll´s dimensions, philanthropy, Gardberg et al. (2019) examine its impact on firms’ reputation. They identify three philanthropic signals that allow firms to improve their reputation: amplitude (i.e. the amount of money donated), dispersion (i.e. spread across many areas), and consistency (i.e. the existence of a corporate foundation).

Additionally, cluster 4 (yellow), labelled "internal CSR", is recognized as an integral component of the same research trend. Centred on the responsible management of companies and CSR, this line of inquiry delves into the internal dimensions of CSR and the influence of stakeholders on reputation. More specifically, it examines how employees and managers play a critical role in driving social and environmental initiatives that not only enhance social and environmental outcomes but also contribute to improved financial performance, ensuring sustainability across all dimensions of the TBL. This cluster has 6 items and is a long way from the central zone, but it is more concentrated than cluster 2.

Some papers within this cluster point to the responsible management of employees as an antecedent of the desired positive link between reputation and firm performance. Mehra et al. (2006) focus on leadership effectiveness in organizations and how social networks, as well as the leader´s integration within these networks, are related to the group's performance. The authors also study how the leader´s reputation in a social network can improve his/her reputation in other circles. Some papers in this cluster examine CEO attributes and their effect on reputation and firm performance (Bugeja et al., 2009; Mukherjee & Sen, 2022). Roberson and Park (2007) reflect on the role of media rankings, such as the Fortune diversity ranking, as a measure of organizational reputation. This ranking gives stakeholders a signal of the internal social responsibility of the company. Accordingly, the authors argue that reputation is also about whether a company is a diversity leader. Also related to media rankings, Odriozola et al. (2018) focus their attention on the MERCO Talent index. This ranking is based on the best human resources management policies and thus indicates the employers of choice.

To conclude, cluster 3 (blue, 7 items), labelled "public and non-profit organizations", is closely linked with the social issues addressed in this research stream and the social dimension of the TBL, including items such as charity and cities (the biggest nodes). Outside the business sphere, this line of research is dedicated to analysing the relationship between reputation and performance in public or non-profit organizations. This is a far-reaching and dispersed cluster, which encompasses recent papers, as indicated by the overlay map.

Within this cluster, some papers extend the field of reputation research to the third sector; for example, the paper by Castilla-Polo et al. (2018) examines the reputation of olive oil cooperatives and its impact on performance. The authors empirically demonstrate that reputation is a key performance indicator to be considered by cooperative managers, because reputation enables the strategic differentiation of these social enterprises in the market. Furthermore, Ba et al. (2022) deal with charities’ reputation and its effect on fundraising by means of crowdfunding and appealing to donors’ attention. As another theme within this cluster, Delgado-García and De Quevedo-Puente (2016) extend the field of firm/corporate reputation to the analysis of cities. They find that, depending on the city configuration, a good city reputation leads to better city performance, and the opposite is also true. Their results can help local public administrations to decide when and how to make efforts to build the city brand.

3.3.2.3Environmental concerns: closing the TBL circleCluster 7 (orange), labelled "environmental performance", encompasses a research stream focused on environmental management and its causes/consequences. Carrying considerably less weight than the line of research dedicated to financial performance (the most relevant) and the line concerning social issues (the second most important), this line of research focused on environmental performance and related policies is applicable to both private and public organizations. In addition to firms’ social and economic performance, the TBL incorporates their environmental performance. As companies face growing pressure from stakeholders to tackle climate change, resource depletion, and ecological degradation, their environmental strategies have become essential to their long-term success. The TBL framework emphasizes that environmental performance goes beyond mere regulatory compliance, with businesses being urged to adopt proactive policies that minimize negative environmental impacts. By embedding environmental considerations into their operations, companies contribute to global sustainability, enhance their reputation, mitigate risks, and ensure their economic and social efforts align with a more sustainable future. For this reason, this cluster closes the circle of the TBL in the reputation-performance literature. It consists of 4 items, the largest of which is environmental policy and corporate environmental strategy. It is located a long way from the central zone and displays a high level of dispersion, yet notably includes recent papers, as indicated by the overlay map.

According to De Miguel (2021), environmental reputation has two antecedents: environmental performance (indicated by the firm's environmental footprint) and environmental policy (actions to reduce the impact of its footprint on the environment). Other papers examine specific environmental contexts such as South Korea, where the integration of firms in chaebols is a very well-known practice that results in the individual reputation of firms being diluted in the collective reputation of the chaebol. In the tourism sector, Becerra-Vicario et al. (2022) empirically demonstrate that environmental practices can improve hotels’ reputation and financial performance. Thus, environmental awareness (precedent, and independent variable) influences reputation (mediator variable), which in turn positively affects the financial performance of the company (consequence, and dependent variable). In the context of increasingly stringent environmental regulation in all countries, Tran and Adomako (2022) study the environmental performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), finding that the ethical behaviour of SMEs has a positive influence on their environmental performance.

3.3.2.4Strategy and competitive issues beyond the economic dimensionInnovation is essential for sustaining the long-term competitiveness of a company. This concept is explored in depth in cluster 5 (purple), labelled “knowledge management” (KM), which introduces the strategic vision of the reputation-performance dynamics in companies. This cluster incorporates KM as a determinant of value creation, which enhances reputation and improves organizational performance. By leveraging KM, businesses can improve their reputation, strengthen relationships with stakeholders, and enhance overall performance, ensuring that all three pillars of the TBL are addressed in a cohesive and sustainable way. This cluster is made up of 5 strongly connected items and is located in the centre of the network visualization map, including items such as focal firm, knowledge and value.

Papers on the topic of reputation tend to approach it as an intangible asset. Similarly, Ginesti et al. (2018) consider intellectual capital as an antecedent of the reputation-financial performance relationship. Given the evident relationship between KM and intangible assets, it is not surprising that there is a group of papers focused on the role of innovation as a key intangible asset needed to develop and identify opportunities for improvement, which is relevant knowledge that affects firm performance. A recent paper in this line by Yu et al. (2022) examines collective reputation cognition and network competence, together with innovation, as drivers of firm performance. Furthermore, Javed et al. (2020) introduce innovation as a mediator variable in the responsible leadership-TBL relationship. The ground-breaking paper by Erden et al. (2015) creates an h-index to measure the reputation of a firm's knowledge stocks, confirming the impact of this intangible asset on firm performance.

The last cluster identified by VOSviewer is cluster 8 (brown), which we call “competitive advantage”. With only 2 items, it includes a small number of papers that focus on business production systems and on how competitive advantages can be generated to positively affect the RPR. This cluster is a long way from the central zone, but it is aligned with the holistic approach of the TBL, showing how competitive advantages, when coupled with socially and environmentally responsible strategies, can enhance overall performance and support sustainable growth. The paper by Afum et al. (2020) contributes to this line of research by examining green manufacturing companies, finding that sustainable practices do not significantly impact their economic performance. A notable aspect of these recent studies is the incorporation of a comprehensive performance evaluation that accounts for specific organizational characteristics.

3.3.2.5Longitudinal view and research trendsTo conclude this section, Table 4 shows how each paper reviewed connects to the research themes identified in the co-citation analysis. It presents the selected articles classified by theme in chronological order to determine the prevalence of each theme over time, thus allowing a parallel historical analysis.

Summary of reputation-performance papers by domain.

| Authors | Citations | Model tested or theoretically supported | Domain (*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hammond and Slocum (1996) | 116 | Prior financial performance as predictor of future reputation | FIN |

| Koh et al. (2009) | 33 | Influence of brand recognition and brand reputation on firm performance. | FIN |

| Ye et al. (2009) | 25 | Seller reputation and sales performance relationship. | FIN |

| Boyd et al. (2010) | 193 | Reputation and performance relationship introducing three models containing faculty experience and prominence together with salary. | FIN |

| Su and Bangassa (2011) | 45 | Relationship of underwriter reputation with IPOs’ under-pricing and long-range performance. | FIN |

| Gatzert (2015) | 117 | Theoretical review of reputation and reputational risk, and performance | FIN |

| Su (2015) | 10 | Impact of investment bank reputation on the long-term stock price performance of IPOs. | FIN |

| Baah et al. (2020) | 88 | Pressure groups’ contribution to reputation (environmental reputation and social reputation), which also significantly affects financial performance | FIN |

| Neville et al. (2005) | 156 | CSR performance-financial performance relationship introducing strategic fit, competitive intensity, and reputation management capability as moderators | FIN/SOC |

| Mehra et al. (2006) | 299 | Executive reputation through external and internal networks and firm performance relationship | FIN/SOC |

| Roberson and Park (2007) | 143 | Assessing the impact of diversity reputation and leadership racial diversity on firm financial outcomes | FIN/SOC |

| Wang and Berens (2015) | 73 | CSR and performance using financial and public reputation as a precursor. | FIN/SOC |

| Castilla-Polo et al. (2018) | 28 | Reputation reflected in four variables—innovation, certification systems, social responsibility and awards—and its relationship with social and financial performance. | FIN/SOC |

| Ginesti et al. (2018) | 66 | Intellectual capital as an antecedent of the reputation-financial performance relationship | FIN/SOC |

| Odriozola et al. (2018) | 9 | Relationship between the labour dimension of corporate social performance and financial performance, as well the inverse relationship. | FIN/SOC |

| Sroufe et al. (2019) | 81 | Impact of sustainability practices on both social sustainability performance and firm financial performance. | FIN/SOC |

| Gonzalez-Rodriguez et al. (2021) | 15 | CSR, reputation, and performance (financial and non-financial). | FIN/SOC |

| Mukherjee and Sen (2022) | 6 | Influence of CEO attributes on corporate reputation, financial performance, and corporate sustainable growth linkages. | FIN/SOC |

| Sánchez-Iglesias et al. (2023) | 0 | Influence of company's financial performance and reputation on customer's corporate perception. | FIN/SOC |

| Bergh et al. (2010) | 92 | Theoretical review of RPR under four theories: Resource Based View, Transaction Cost, Signalling Theory, and Social Status Research. | STR |

| Ou et al. (2012) | 22 | Ethical sales behaviour, salesperson expertise, service performance, corporate reputation, and corporate performance as antecedents of consumer loyalty. | STR |

| Erden et al. (2015) | 8 | Relationship between a firm's reputation in knowledge stocks within both scientific and business communities, and the influence of these assets on firm performance. | STR |

| Fanasch (2019) | 21 | Corporate reputation and eco-certification as intangible factors affecting corporate performance. | STR |

| Afum et al. (2020) | 59 | Green manufacturing practices, operational competitiveness, firm reputation, and sustainable performance dimensions. | STR |

| Javed et al. (2020) | 21 | Mediating role of corporate reputation and innovation in the responsible leadership–TBL relationship. | STR |

| Lau et al. (2020) | 8 | Reputation as moderator of the relationship between closeness and betweenness and firm performance. | STR |

| Yu et al. (2022) | 8 | Relationships among collective reputation cognition (measured by innovation capabilities, brand image and transaction fairness), network competence and innovation performance. | STR |

| Eltantawy et al. (2009) | 57 | Supply Management Ethics Responsibility (SMER) and supply management performance introducing strategic supply management skills and supply management perceived reputation into the model. | STR/SOC |

| Subramaniam et al. (2019) | 34 | Analysing the impact of supplier development practices on suppliers' social performance. | STR/SOC |

| Bugeja et al. (2009) | 26 | CEO reputation, turnover rates, and future board seats. | SOC |

| Delgado-Garcia and Quevedo-Puente (2016) | 11 | Relationship between city reputation and city performance | SOC |

| Gardberg et al. (2019) | 35 | Philanthropy and Corporate Social Performance (CSP) reputation, understood as CSP awareness and CSP perception. | SOC |

| Singh and Mishra (2021) | 105 | Corporate reputation as a moderator of the CSR-organizational performance relationship | SOC |

| Ba et al. (2022) | 10 | Impact of charities’ reputation and social capital on medical crowdfunding performance | SOC |

| Feng et al. (2022) | 18 | Influence of CSR dimensions (employee, customer, community, and environment) on sustainable business performance, introducing reputation as a mediator. | SOC |

| Yan et al. (2022) | 9 | Influence of CSR, especially with employees, on reputation. | SOC |

| Winit et al. (2023) | 8 | Refining the quality of consumer relationships and enhancing perceived reputation through sustainability performance disclosure. | SOC |

| S. Kim et al. (2021) | 23 | Environmental performance-market value relationship. | ENV |

| De Miguel (2021) | 12 | Environmental performance and environmental policy as antecedents of corporate environmental reputation. | ENV |

| Tran and Adomako (2022) | 8 | Moderating role of reputation in the relationship between environmental regulation and environmental performance. | ENV |

| Becerra-Vicario et al. (2022) | 5 | Environmental performance and financial performance through its impact on reputation. | ENV |

(*) Finance (FIN); Strategy (STR): Social (SOC); Environmental (ENV).

Source: Own elaboration based on WoS data.

As can be observed in Table 4, the earliest studies primarily lie within the financial discipline, and were mainly published in the first half of the analysed period. Later, the strategic perspective on the RPR begins to emerge, and continues until the end of the analysed period. This suggests that the economic dimension of the TBL is a thread that runs through the entire analysed period covering the oldest and the most recent paper reviewed (Hammond & Slocum, 1996; Sánchez-Iglesias et al., 2023).

The situation differs for the development of the social dimension of the TBL. In this case, the studies appear throughout the analysed period, but there is a delay that coincides with the publication of the paper by Neville et al. (2005). A novel feature of the papers addressing the social dimension of the TBL is that some are connected with the economic dimension, in terms of both financial and strategic aspects. Thus, within the papers classified under a social/financial orientation, we observe that many of them analyse the role of the different aspects of CSR in improving reputation and performance, or vice versa. Examples include the papers by Mehra et al. (2006) and Mukherjee and Sen (2022), addressing CEO reputation and firm performance; Wang and Berens (2015), supporting the relationship between public reputation and financial performance; and Castilla-Polo et al. (2018), examining various different variables—awards, certifications, CSR and innovation—that can explain social and financial performance. On the other hand, when the social dimension is combined with a strategic approach, the focus is on the supply chain and its relationship with corporate reputation (Eltantawy et al., 2009; Subramaniam et al., 2019).

The environmental dimension of the TBL is the most recent to emerge, with the related papers being published from 2021 onwards and focusing on environmental performance as a driver and/or consequence of reputation (Kim et al., 2021; De Miguel 2021; Tran & Adomako, 2022 and Becerra-Vicario et al., 2022).

In line with the multidimensional nature of the TBL, there has been a shift from a financial focus to a multidisciplinary focus. Without overlooking financial concerns, which are also strategic and fall under the economic dimension of the TBL, other considerations are being introduced into analyses of the RPR, such as social aspects (an area with many published papers) and environmental considerations (an area where the number of studies is growing and expected to increase even further in the future).

3.4Thematic analysis with ATLAS.tiA thematic analysis was conducted to complement the bibliometric analysis. This was done to verify the validity of the algorithm's findings while also delving deeper into the content of the selected papers, particularly in the discussion and conclusion sections. In a deductive manner, based on the previously defined categories and clusters (introduced here as codes), we chose specific quotations from the selected articles to clearly illustrate the theme and its focus. It is worth noting that in thematic analysis the purpose of coding is to find evidence to support the themes (Clarke et al., 2015). It is also important to highlight that a quotation in qualitative analyses is equivalent to numerical data in quantitative analyses (Patton, 2015).

Fig. 6 shows the network of categories and a selection of illustrative quotations. The number on the left of each category indicates its density, while the number on the right shows its connections with other categories. The colours of each category also reflect the density of the theme within the set of analysed papers. The quotations provide us with further evidence and support for our previous findings and interpretations.

To explain the network created with ATLAS.ti (version 7.5.18), we focus on the components of the TBL, the key categories (themes) and quotations. Fig. 6 shows a small selection of quotations as examples of the analysis done. It is noteworthy that some quotations are linked to more than one theme, demonstrating the richness of the academic studies conducted and the interconnection of the themes. The network provides a comprehensive overview of how different aspects of reputation influence and are influenced by various performance dimensions, illustrating the need for a holistic approach to understanding and managing corporate reputation.

Although the TBL theoretical framework appears at the top of the network (example quotation: “TBL performance measures a firm's financial, social and environmental performance simultaneously”), the link between reputation and performance is the central theme of the network. This is exemplified by the following quotation, also related to strategy: “a strong reputation is a powerful tool in the search for competitive advantage, as shown by studies linking reputation to performance".

The category “financial performance” encompasses the study of the relationship between reputation and financial metrics such as profitability, ROI, and revenues, as demonstrated by the following quotation: "reputation is an intangible resource that has financial consequence". Another good example, also related to environmental performance and strategy, is the following quotation: "…impact of reputation and eco-certification on firm performance, which is considered the company's survival in a highly competitive environment".

The category “competitive advantage” includes the question of how a good reputation can lead to a competitive edge in the market, as indicated by this quotation (which is also related to the KM category): "despite the relevance of intellectual capital (IC) in creating companies’ value and competitive advantage being continuously under the scrutiny of academics, prior empirical studies have overlooked the relationship between IC and corporate reputation".

The category “social performance” focuses on how reputation impacts an organization's social responsibilities and community engagement, with quotations such as “Scholars have turned to the concept of corporate social performance (CSP) in an effort to justify arguments for why management should, or should not, focus on socially responsible behaviours". Other quotations also link social with environmental aspects, in clear alignment with the TBL framework, such as "green manufacturing has a positive significant impact on social, economic, and environmental performance".

Under the social dimension of the TBL, the “internal CSR” category focuses on how internal CSR practices, such as human capital management, affect reputation and performance. A sample quotation is “companies interested in achieving a good reputation should increase their attention to human capital assets, a strategy of assessment of employees’ knowledge, skills, experience". The quotation “city reputation can either positively or negatively affect city performance…” is a good example of the category “public and non-profit organizations”.

Especially relevant for the category “environmental performance”, which explores the relationship between a company's reputation and its environmental practices, is this quotation: “green manufacturing has a positive significant impact on social, economic and environmental performance”. This quotation also comes under the lens of the TBL.

To sum up, the network indicates a multifaceted relationship between reputation and various dimensions of performance, demonstrating the importance of considering multiple factors when evaluating corporate reputation. The thematic analysis extends the traditional financial framework to the TBL, validating the clusters found in the previous bibliometric analysis as overarching patterns or themes. The analysis also confirms that, while the financial focus is the most prevalent, it is closely followed in importance by a social focus and a promising new environmental focus.

4DiscussionStarting with RQ1, about the main areas of interest in the research conducted to date on the relationship between reputation and performance, our analysis of this field with the software VOSviewer has allowed us to satisfactorily answer this question. In addition, we have shown that the major topics that shape the RPR research resemble the well-known TBL framework proposed by Elkington (1994) (economic, social, and environmental issues). We have identified four overarching research trends: finance (inherently tied to the economic pillar of the TBL), CSR and sustainable practices (focused on social performance, public and non-profit organizations, and internal CSR, and thus clearly tied to the social pillar of the TBL), environmental concerns (tied to the environmental pillar of the TBL), and strategy and competitive issues (tied to all three pillars of the TBL).

While the financial discipline was dominant in the early days of this literature, the management discipline now plays a prevalent role, incorporating social and environmental performance. Additionally, the economic discipline has a limited presence, contributing to the reputation-performance analysis from a micro-level perspective, through the study of organizational performance.

Regarding RQ2, about the arguments supporting (or against) the RPR, evidence of a positive relationship can be found in most of the papers, clusters and themes. Numerous variables have been included in analyses of the RPR in an effort to shed light on the relationship and the elements that mediate or moderate it. In fact, there are very few papers—five in total—that exclusively examine the specific relationship between these two variables alone (Koh et al., 2009; Boyd et al., 2010; Fanasch, 2019; Subramaniam et al., 2019; Baah et al., 2020). Indeed, while the focus in early research was on these two variables (cluster 1), it is evident that the number of variables tested has significantly increased over time (cluster 6). Moreover, Boyd et al. (2010) argue that the relationship between the two variables should be positive as long as reputation is considered a chain of actions involving multiple resources. According to these authors, the Resource-Based View is the appropriate theoretical lens, rather than simplistic views of reputation as an aggregate. This justifies the inclusion of additional variables to better understand the relationship under study.

To provide a more comprehensive answer to RQ2, we introduce the links between the identified clusters and the main topics within each cluster supporting either a positive or negative (mediating/moderating) influence on the RPR. We start by analysing the topics associated with a positive impact on this relationship.

The most recent and relevant addition in this regard is the incorporation of CSR and sustainability in their different roles. Clusters 2 and 4 provide a comprehensive overview of studies exploring the integration of sustainability practices into building a “sustainable reputation” (Gardberg et al., 2019; Sroufe et al., 2019) as well as introducing social performance alongside traditional variables used to measure performance. Within an accounting approach to reputation, some papers, such as the one by Baudot et al. (2020), interpret reputation as an accountability mechanism. In this respect, perspectives on corporate accountability have extended conventional debates on CSR to a broader group of stakeholders, including civic accountability to the people living where firms operate. Wang and Berens (2015) introduce public and financial stakeholders and explore how the different dimensions of CSR affect reputation and financial performance. Winit et al. (2023) show how the impact of CSR disclosures on reputation extends beyond mere commentary on output. This view is also shared by Neville et al. (2005) when they conclude that corporate reputation is the vehicle through which CSR initiatives affect business performance. More specifically, these authors introduce reputation management as a moderator variable in the relationship between corporate social performance and financial performance.

One common conclusion (clusters 2 and 4) is that firms with a reputation for sustainability are more valued by the market than firms without such a reputation. However, it is also recognized that it is possible to achieve a high market value even without a good sustainability reputation. Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984) is a widely-used framework in the papers in these two clusters, since it seems clear that a “good relationship” with stakeholders necessarily involves accounting for sustainability concerns. Sustainability practices are also analysed by Sroufe et al. (2019), who find that such practices lead to a better sustainability reputation and financial performance. Most of the papers reviewed introduce CSR as an antecedent of performance and reputation as a moderator of its relationship with financial performance (Neville et al. 2005; Wang & Berens, 2015; Singh and Mishra, 2021; Feng et al., 2022). Odriozola et al. (2018) also find that CSR leads to improved financial performance, but the causality does not run in the opposite direction. In addition, González-Rodríguez et al. (2021) conclude that the influence of CSR on performance through reputation is much stronger for long-term performance (non-financial performance) than short-term performance (financial performance).

In cluster 4, the focus on human capital introduces the role of employees as a strategic stakeholder group that can improve firms’ reputation and subsequently their performance. Odriozola et al. (2018) report evidence that labour reputation improves the financial performance of Spanish companies listed as one of the “best places to work”. Similarly, Ginesti et al. (2018) analyse human capital efficiency and Yan et al. (2022) examine the role of employee-oriented CSR activities in building a corporate reputation. Finally, the role of CEO attributes and their influence on reputation has been analysed in relation to this topic (Bugeja et al., 2009; Mukherje and Sen, 2022). In this vein, Javed et al. (2020) analyse sustainable leadership and performance, finding evidence to support the role of reputation as a mediator of the relationship with socio-economic performance but not environmental performance.

Additionally, some papers in cluster 7 examine the relationship between environmental performance and reputation, but these papers are mainly oriented towards reputational risk, as we discuss below. Among those centred on the positive impact on performance, Becerra-Vicario et al. (2022) analyse the relationship between environmental performance and financial performance, and the mediation effect of reputation. Tran and Adomako (2022), focusing on SMEs, find that environmental reputation generates superior environmental performance benefits. Also, De Miguel (2021) examines the role played by the quality of environmental policy in improving a firm's environmental reputation and enhancing its environmental performance, finding that only one dimension of CSR, the environment, improves results.

Conversely, some papers in cluster 7 present conflicting findings on the value of environmental reputation for achieving better performance. Reputational risks are introduced into research models to explain a decline in performance (Gatzert, 2015). A holistic perspective regarding the interaction between corporate reputation, reputation-damaging events and financial performance is offered by Gatzert (2015), who finds that corporate reputation strongly depends on the type of event, with fraudulent or criminal events typically being identified as causing the most severe financial (reputational) losses. Legitimacy Theory supports the consideration of social and environmental concerns, recognizing that markets increasingly demand attention be paid to both financial and non-financial performance aspects. It is a framework that is especially well suited to analyses of the environmental performance-reputation relationship.

Regarding environmental concerns (cluster 7), Abdulaziz-al-Humaidan and Almaiman (2024) and Hammami and Othmani (2024) have recently demonstrated how green management practices influence enterprises’ reputation. Along the same lines, but also addressing human capital concerns (cluster 4), the paper by Anser et al. (2024) contributes to a better understanding of how to improve corporate performance by focusing on green intellectual capital and its components; namely, green human capital, green structural capital and green relational capital.

The intangible nature of reputation justifies the application of Intellectual Capital Theory to the RPR (Ginesti et al., 2018; Fanasch, 2019; Anser et al., 2024). Cluster 5, about KM, deals with the superior performance of firms that effectively share knowledge internally. For example, Yu et al. (2022) confirm the relationship between collective reputation cognition—measured by innovation capabilities, brand image and transaction fairness— and network competence, and the effects of both of these variables on firms’ innovation performance. Erden et al. (2015) introduce knowledge-based reputation into their analysis as a determinant of firm performance. Under the umbrella of the Resource-Based View, Fanasch (2019) explores how some related intangible resources, such as eco-certifications, influence corporate performance and help differentiate companies from their competitors. However, the process of certification must be transparent to be trustable, and to prevent greenwashing. Adapting to changing economic conditions and implementing innovative strategies are key to maintaining and improving competitiveness. Finally, in the non-business field, cities (Delgado-García and De Quevedo-Fuente, 2016) and social entities (Castilla-Polo et al., 2018) are analysed in cluster 3 to produce additional evidence of the RPR.

In addition, the evidence against the RPR (that is, papers that find no significant relationship or even inconsistency in terms of the direction of the relationship) cannot be specifically associated with any one cluster. Thus, it is common to find reverse causality (Cocis et al., 2021) or a two-way relationship (Rose & Thomsen, 2004; Castilla-Polo & Sánchez-Hernández, 2021).

One recurring argument explaining the contradictory evidence on the RPR is the lack of a longitudinal perspective in most papers, particularly those in clusters 1 and 6, which are focused on financial issues. It is common for studies to utilize one-year periods of analysis. The few exceptions include the paper by Hammond and Slocum (1996), who conduct an 11-year analysis to corroborate the effect of previous performance on future reputation; Cocis et al. (2021), who study the airline industry from 2016 to 2018; and Bugeja et al. (2009), who measure the performance of firms that are the target of a takeover as their buy-hold abnormal return over the period from 24 to 6 months prior to the takeover announcement, finding that the directors' reputation is associated with a lower turnover rate and a higher increase in future board seats.