This paper investigates the effects of attitudes towards sustainable consumption and sustainable behaviours. Income as the control variable and gender, age, assets, and educational level as moderators were included. To achieve the aims of the study, a critical literature review, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modelling were performed. Data were obtained using the CAWI technique on a sample of 1200 adult consumers. The findings show that attitudes towards sustainable consumption are positively associated with sustainable behaviours, and that income significantly determines dimensions of attitudes towards sustainable consumption and sustainable behaviours. Additionally, the relationships between income, dimensions of attitude towards sustainable consumption, and particular sustainable behaviours in groups distinguished by gender, age, property ownership, and education level were confirmed.

One of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), defined in UN's 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, is individual consumption—specifically, Goal 12: ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns (United Nations, 2015). Even in this 15-year plan, simple changes in consumption can have a large impact on the whole society, environment, and economy. Sustainable consumption can lead to sustainable development (Reisch & Thøgersen, 2017). Notably, individual consumers who are aware of consumption consequences and want to limit the negative impact of acquiring, using, and disposing of products can demand sustainable products and services (Kim et al., 2012). However, producers, through making goods and providing services, enable consumers to realise attitudes in the market. In addition to individual changes, policy transitions are required to allow sustainable development (Stevens, 2010).

Many studies have analysed sustainable consumption using the consumer perspective. While some researchers have evaluated the attitudes towards sustainable behaviours, others have focused on behaviours. Consumers are becoming increasingly concerned about the environmental, social, and economic consequences of consumption (Harjadi & Gunardi, 2022), leading to positive attitudes towards sustainable behaviours (Park & Lin, 2020). Such consumers tend to be more aware of consumption consequences, are willing to spend more on sustainable products, and feel the impact of their sustainable consumption (Auger et al., 2003; Esmaeilpour & Bahmiary, 2017). Various examples of the positive association between attitudes towards sustainable consumption and sustainable practises have been reported in the literature (Ahamad & Ariffin, 2018; Esmaeilpour & Bahmiary, 2017; Essiz & Mandrik, 2022; Razzaq et al., 2018; Song & Ko, 2017).

We used attitude as the predictor of behaviours according to the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). On the basis of the TPB, the social cognitive theory, and the attribution theory, favourable evaluation of sustainable practices may be influenced by beliefs about the potential consequences of behaviours and feeling the real impact of individual behaviours named as self-efficacy. The willingness to spend more on sustainable products and services is typically considered representative of what consumers truly believe (Auger et al., 2003). However, some authors have highlighted that consumption practices do not always reflect attitudes towards sustainable consumption (Aschemann-Witzel & Aagaard, 2014; Carrington et al., 2014; Park & Lin, 2020; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019), leading to an attitude–behaviour gap.

To consider the whole consumption process, we used the sustainable consumption behaviours (SCB) cube model, which distinguishes three stages of consumption: acquisition, usage, and disposal of products or services (Geiger et al., 2018). The literature lacks a broad approach to sustainable consumption. Studies have typically focused on a particular component of sustainable behaviours, including a stage, such as acquisition (Balderjahn et al., 2018; Pepper et al., 2009) or disposal (Garcia-Montiel et al., 2014; Wakefield & Axon, 2020), or a specific sector, such as fashion (Muthu, 2019; Park & Lin, 2020), food (Anh et al., 2020; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019) and tourism (Hasana et al., 2022; Thukia et al., 2022). Other studies have restricted their evaluation to a specific group of consumers, such as schoolchildren aged 9–18 years (Wichmann et al., 2022), students (Bauerné Gáthy et al., 2022), young adults (Kreuzer et al., 2019), or to an environmental context (Bamberg & Möser, 2007; Gifford & Nilsson, 2014; Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). We speculated that a broad approach to sustainable behaviours, including all stages of consumption not narrowed to one sector or consumer group, may fulfil the identified gap. In the current study, we analysed the effects of attitudes towards sustainable consumption and sustainable behaviours with special consideration of income as a determinant and different consumer groups. A better understanding of the attitude–behaviour gap supports policy interventions focused on individual-level behaviour change.

Against this background, we formulated the following specific research objectives:

RO1. Identify items of attitudes towards sustainable consumption (ATSC) and sustainable behaviours constructs;

RO2. Examine the relationship between ATSC and particular sustainable behaviours;

RO3. Analyse personal income as a control variable of ATSC dimensions and particular sustainable behaviours; and

RO4. Analyse the relationship between income, ATSC, and its dimensions or particular sustainable behaviours in groups distinguished by gender, age, property ownership, and education level.

This paper is divided into six section. Section 2 reviews the literature to provide a framework for further analysis. Section 3 characterizes the methods used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA method was the first phase of implementing the structural equation model (SEM). Section 4 presents the results of the exploratory factor analysis, the measurement model, and the group analysis. To verify the results, we used bootstrap (Section 5). Finally, Section 6 presents the discussion and conclusions.

2Literature reviewThe sustainable consumer is aware of the external consequences of consumption. Sustainability in the context of consumption is understood as a guideline for searching for a balance between satisfying an infinite number of needs and responsibility for the Earth and others (Balderjahn, Peyer et al., 2013; Piligrimiene et al., 2020). A consumer trying to achieve sustainable consumption minimises the environmental, social, and economic consequences to achieve intragenerational and intergenerational justice (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2020a).

Attitudes differ from real behaviours. We defined attitudes towards sustainable behaviours as the appraisal of sustainable behaviours and the favourable or unfavourable evaluation of such activities (Ajzen, 2011; Essiz & Mandrik, 2022). According to the TPB, attitudes among subjective norms and perceived controls influence intentions to perform behaviours (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). By contrast, intentions are the best predictor of behaviours. According to the TPB, attitudes are influenced by beliefs about the potential consequences of behaviours and evaluations of behavioural results (Ajzen, 2020; Heimlich & Ardoin, 2008). Beliefs about the potential consequences are similar to outcome expectancies, which are included according to the social cognitive theory (SCT) to the factors shaping behaviours. The remaining determinants included in SCT are goals, self-efficacy, and sociostructural variables (Bandura, 1986; Conner & Norman, 2005). Another theory demonstrating the importance of the efficacy concept is the attribution theory proposed by Heider (1958) and developed by Weiner (1985). Attribution theory postulates that individuals link causes to events. If something happens because of one's effort, it can be controlled and changed, which means that people have the motivation to behave accordingly.

A study by Song and Ko (2017) on perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours towards sustainable fashion exemplifies attitude analysis in a sustainable context. They demonstrated that the four identified types of consumers have similar age or gender but differ significantly in monthly household income or monthly spending on fashion products. Esiz and Mandrik (2022) demonstrated the intergenerational influence on sustainable consumer attitudes. Esmaeilpour and Bahmiary (2017) explored the impact of environmental attitudes on the decision to purchase a green product and illustrated the significant and positive impact of the environmental attitude of consumers on the decision to purchase a green product. Razzaq et al. (2018) also revealed a significant and positive impact of proenvironmental attitude but on sustainable clothing consumption. Ahamad and Ariffin (2018) identified a significant relationship between knowledge, attitude, and practices towards sustainable consumption of students in Malaysia. Thus, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1. ATSC is positively associated with sustainable behaviours.

However, individual- and context-specific barriers may hinder desired sustainable consumption behaviours (Gleim et al., 2013; Toussaint et al., 2021). The attitude–behaviour gap also exists in the context of sustainability (Aschemann-Witzel & Aagaard, 2014; Carrington et al., 2014; Juvan & Dolnicar, 2014; Park & Lin, 2020; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019). The account for variations in concern and behaviours as a considerable complex is highlighted by Gifford and Nilsson (2014). They emphasised the role of personal and social factors and natural forces, technological innovations, and governance instruments as factors affecting proenvironmental concern and behaviour (Gifford & Nilsson, 2014).

The relationship between attitudes and behaviours is analysed using different approaches in the context of consumers. Researchers have focused on selected sectors, for example, fashion (Razzaq et al., 2018; Song & Ko, 2017), food (Aschemann-Witzel & Aagaard, 2014; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019) or selected areas such as ethical consumption (Carrington et al., 2014).

Geiger et al. (2018) proposed the cube model of sustainable consumption behaviours (SCB cube model), in which consumption phases as one of three issues are included. According to the SCB cube model, consumption comprises three stages: acquisition, usage, and disposal of products or services (Frezza et al., 2019; Lim, 2017; Peattie & Collins, 2009; Phipps et al., 2013). Therefore, the consumer role is not restricted to market-based purchases but includes three equally essential phases (Hwang et al., 2020). Additionally, sustainability dimensions are included in the SCB cube model, socioeconomic and ecological (Geiger et al., 2018). However, in this article, the analysis of three dimensions—social, economic, and environmental—are enclosed separately (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2020b).

When it comes to the effect of income on the behaviours of consumers, there is no consensus. Franzen and Vogl (2013) emphasise that income measurement does not consider inherited wealth or other assets and indicate that wealth is a more optimal measure. Owing to lack of radical budget constraints, wealthier people can take on extra costs for sustainable products and services. Some authors have highlighted that the more affluent do not have to worry about expenditures and may pay attention to other concerns (Franzen & Vogl, 2013); therefore, they are more interested in quality of life issues (Kim & Wolinsky-Nahmias, 2014). Thus, income positively affects the probability of buying ethically (Starr, 2009) and environmental concerns (Franzen & Vogl, 2013). By contrast, wealthier individuals consume more and extend consumption consequences, such as carbon footprint (Lazaric et al., 2020). Of note, some sustainable practices are not expensive but more time-consuming. However, whether wealthier consumers are eager to be involved in sustainable behaviour remains unclear. Lo (2016) identified that lower-income individuals are more willing to limit driving for environmental reasons. Roberts (1996) reported that income is negatively correlated with ecologically conscious consumer behaviours. Considering this inconsistency, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2. Income significantly determines the dimensions of ATSC and sustainable behaviours.

We reviewed the literature about different groups distinguished by different socioeconomic groups. However, no study has included a detailed income analysis as the control variable in particular groups distinguished by different socioeconomic characteristics. Considering the identified gap, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H3. Factors such as gender, age, property ownership, and education level impact the strength of the relationship between income, ATSC, and its dimensions or particular sustainable behaviours.

3MethodsWe first conducted EFA by using IBM SPSS Statistics to ensure valid measures of constructs. The reliability and validity of the scales were verified using the following measures: p value, Cronbach alpha, average variance extracted (AVE), and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The results allowed us to extract the items and dimensions for both ATSC and sustainable behaviours.

The relationships between ATSC and sustainable acquisition, usage, or disposal of goods were verified using structural equation modelling (SEM). The maximum likelihood method in SPSS Amos v. 16 (Byrne, 2010) was used for both part of the SEM: measurement model (CFA) and for cause-and-effect models. SPSS Amos allowed us to analyse complex relationships between latent and observable variables. The selected method of analysis required an appropriate construct of the survey questionnaire. Most questions were based on a five-point Likert scale, which can be treated as interval one (Mondiana et al., 2018). We also analysed corresponding groups of respondents to investigate the differences in the considered relationships between them.

The estimated SEM model was statistically validated using the chi-square, df, RMSEA, IFI, and Tucker–Lewis index (Bollen, 1989). Robustness of the results was examined using the bootstrap method to re-estimate the main SEM model and compare the results (Efron & Tibshirani, 1986).

3.1ItemsThe survey questionnaire was developed based on the literature review, previous studies, and experts’ opinions. The initial pool of items was generated mainly on the basis of the SCB cube model (Geiger et al., 2018), TPB, SCT, attribution theory, and consciousness for sustainable consumption scale (Balderjahn, Buerke et al., 2013) and reviewed by an expert group comprising seven academic researchers in economics and management. In a pilot study, we distributed the questionnaire to 100 students. Based on the feedback, the items were revised to capture the constructs’ essence and eliminate any questionnaire flaws.

The final questionnaire comprises three groups of items: demographic characteristics, which includes nominal and cardinal data, as well as sustainable behaviours and ATSC, which contain ordinal data and are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.”

3.2Data collectionSurvey data were collected using CAWI techniques in August 2022 from 1200 adult respondents from Poland. The respondents were divided into three groups based on the monthly median disposal income per person in their household: ≤2160, 2160–5760, and ≥5760 PLN). A sample of 400 in each of the analysed groups guarantees reliable results with a confidence level of 95 % and a maximum estimation error of 5 %.

3.3Respondents’ demographic characteristicsThe respondent profile (Table 1) comprised 47.8 % male and 52.2 % female respondents. Most of them own assets worth >200,000 PLN. The medium value of owned assets is approximately 100,000 PLN, and one-fourth of respondents do not have assets worth >20,000 PLN. Only 54 of 1200 individuals had primary education. Secondary and tertiary education have almost 35 % and 24 % respondents, respectively. Almost 40 % of the respondents were ≥55 years old, and approximately 25 % were 18–34 years old.

Respondents’ demographic characteristics.

In Poland, 48.3 % of the overall population is male. Most adults are 35–44 years old (18 %). In ages 25–34 and 45–54, respectively, 14.3 % and 14.6 % of adults. Tertiary education: 23.1 % of the population and 32.4 % graduated from secondary school (stat.gov.pl). Therefore, the distribution of the values of individual demographic features is very similar to the data from the conducted study. It can be assumed that the sample reflects Poland's adult population correctly, including gender, age, and education characteristics.

4Results4.1EFAEFA was conducted to establish valid measures for both groups of analysed constructs: ATSC and sustainable behaviours. In both cases, variables fit the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin criterion (KMO > 0.8), so the dataset was suitable for factor analysis (Kaiser, 1970). The number of components for each construct was established based on the K1 criterion, parallel method, and scree plot (Bandalos, 2018). Because it was assumed that factors could be correlated with each other, principal axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation was used (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006).

According to the K1 criterion, there should be as many components as long as initial eigenvalues are >1. In parallel analysis, only those factors whose eigenvalues are greater than the eigenvalues from the random data should be retained (Hayton et al., 2004). To conduct parallel analysis in SPSS, the syntax proposed by O'connor (2000) was used. The least precise method is the scree plot because it is based on a visual assessment of the moment of flattening of the figure (Bandalos, 2018). Each method of EFA analysis (Table 2 and Fig. 2) confirms that in both cases, the analysed group of items converges on three factors.

Exploratory factor analysis.

| Component | Attitude Towards Sustainable Consumption | Sustainable Behaviours | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Eigenvalues | Parallel | Initial Eigenvalues | Parallel | |||||

| Total | % of Var | Cum.% | Mean | Total | % of Var | Cum.% | Mean | |

| 1 | 9.578 | 56.344 | 56.344 | 1.159* | 4.571 | 38.095 | 38.095 | 1.165* |

| 2 | 1.066 | 6.270 | 62.613 | 1.050* | 2.490 | 20.751 | 58.847 | 1.122* |

| 3 | 1.012 | 5.950 | 68.563 | 1.010* | 1.108 | 9.234 | 68.080 | 1.089* |

| 4 | 0.757 | 4.455 | 73.018 | 1.004 | 0.635 | 5.293 | 73.373 | 1.061 |

| 5 | 0.690 | 3.901 | 76.919 | 1.002 | 0.550 | 4.580 | 77.954 | 1.033 |

| KMO indicator | 0.917 | 0.866 | ||||||

Initial eigenvalues are greater that the eigenvalues’ means from the random data (Hayton et al., 2004).

In the first step of EFA analysis, sustainable consumption behaviours were divided into three phases according to the SCB cube model (Geiger et al., 2018): acquisition (11 items), usage (6 items), and disposal (6 items). EFA also allowed us to define an ATSC as the awareness of consumption consequences (6 items), reliability of real impact on sustainable consumption (6 items), and the acceptance of spending more on sustainable products and services (5 items).

The variables with factor loadings of <0.5 were removed from further analysis, so the total number of final items was reduced from 40 to 23 (Black et al., 2006). The results obtained in EFA were based for CFA. The variables included in each factor are listed in the assessment of the measurement model point (Table 3).

Item loadings, reliability, and validity of final constructs.

EFA made it possible to define the factors included in the composition of ATSC, sustainable behaviours, and the items below. It was the basis for constructing a conceptual framework that illustrates the expected relationships adequate to the hypotheses put forward in the literature review of the article. Fig. 2 illustrates the relationships that will be tested during the estimation of the SEM.

4.3Assessment of the measurement modelTable 3 presents the results of the confirmatory factor analysis–measurement model. The model was estimated with a significance level of 0.05. Loadings for each variable are significant and >0.6 (Table 3). The minimum loading recommended value in the literature is 0.5 (Black et al., 2006). The statistics of both Cronbach's alpha and C.R. for the constructs in this study are >0.7, implicating the scale's reliability (Cortina, 1993). The AVE in each case was >0.5, which means that the convergent validity of the model was also established (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

We analysed the ATSC as a factor consisting of consumption consequences, the real impact of sustainable consumption and spending more on sustainable products and services. The loadings for the second-level construct were also >0.5. The values of Cronbach's alpha, C.R., and AVE statistics confirm its’ reliability and convergent validity.

4.4Discriminant validityDiscriminant validity was measured using the HTMT ratio (Henseler et al., 2015). For all combinations of factors, the measure was <0.9, which confirms the discriminant validity of this study (Table 4).

4.5Hypothesis testing (direct effect) with control variablesThe impact of the ATSC on each stage of sustainable consumption behaviours was significant. The more consumers know about consumption consequences and their actual impact on sustainable consumption and accept spending more on sustainable products and services, the more often they buy, use, and dispose of goods or services sustainably (Table 5). Notably, the relationship between ATSC and acquisition is the strongest (α1 = 0.758).

SEM model results.

| Parameters | Relation | Estimate | S.E. | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | ATSC -> Acquisition | 0.758* | 0.044 | <0.001 |

| α2 | ATSC -> Usage | 0.542* | 0.053 | <0.001 |

| α3 | ATSC -> Disposal | 0.599* | 0.039 | <0.001 |

| β1 | Net income -> CC | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.485 |

| β2 | Net income -> SMSPS | 0.083* | 0.014 | 0.006 |

| β3 | Net income -> RISC | 0.035 | 0.016 | 0.257 |

| β4 | Net income -> Acquisition | 0.079* | 0.016 | 0.010 |

| β5 | Net income -> Usage | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.607 |

| β6 | Net income -> Disposal | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.432 |

Furthermore, the measure used as a control variable also significantly impacts sustainable consumers’ attitudes and behaviours. Higher net income achievement implicates not only increasing acceptance for spending more money on sustainable products and services (β2), but also real, more widespread sustainable acquisition (β4). In the base model, the impact of net income on other analysed factors was statistically nonsignificant.

The following measures confirmed the goodness of fit of the estimated model: IFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.909 (> 0.85), RMSEA = 0.069 (<0.08), and CMIN/DF = 1.689 (<2.00) (Bollen & Curran, 2005; Byrne, 1989).

4.6Group analysisThe next step was to analyse the relationship between ATSC and real sustainable consumption behaviours in groups distinguished by gender, age, assets, and education level (Table 6–9). The groups based on age, assets, and education level were distinguished based on medium value.

SEM model results by respondents’ gender.

| Param. | Relation | Women | Men | Diff. | T stat. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||||

| α1 | ATSC -> Acquisition | 0.727 | <0.001 | 0.791 | <0.001 | −0.064 | −1.557 |

| α2 | ATSC -> Usage | 0.512 | <0.001 | 0.584 | <0.001 | −0.072 | −1.184 |

| α3 | ATSC -> Disposal | 0.577 | <0.001 | 0.603 | <0.001 | −0.026 | −0.371 |

| β1 | Net income -> CC | −0.031 | 0.459 | 0.109⁎⁎ | 0.015 | −0.140 | −2.058* |

| β2 | Net income -> SMSPS | 0.074 | 0.079 | 0.116⁎⁎ | 0.010 | −0.042 | −0.643 |

| β3 | Net income -> RISC | 0.029 | 0.487 | 0.062 | 0.166 | −0.033 | −0.523 |

| β4 | Net income -> Acquis. | 0.080 | 0.060 | 0.094⁎⁎ | 0.035 | −0.014 | −0.210 |

| β5 | Net income -> Usage | −0.037 | 0.403 | 0.083 | 0.074 | −0.120 | −1.843 |

| β6 | Net income -> Disposal | −0.025 | 0.571 | 0.095⁎⁎ | 0.034 | −0.120 | −1.731 |

| Goodness of fit | IFI = 0.920RMSEA = 0.069 | IFI = 0.905RMSEA = 0.069 | |||||

SEM model results by respondents’ age.

| Param. | Relation | <44 years | 44 years or more | Diff. | T stat. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||||

| α1 | ATSC -> Acquisition | 0.846 | <0.001 | 0.684 | <0.001 | 0,162 | 4.085* |

| α2 | ATSC -> Usage | 0.669 | <0.001 | 0.508 | <0.001 | 0,161 | 2.773* |

| α3 | ATSC -> Disposal | 0.647 | <0.001 | 0.535 | <0.001 | 0,112 | 1.613 |

| β1 | Net income -> CC | 0.020 | 0.664 | 0.010 | 0.813 | 0.010 | 0.152 |

| β2 | Net income -> SMSPS | 0.055 | 0.228 | 0.102⁎⁎ | 0.013 | −0.047 | −0.718 |

| β3 | Net income -> RISC | 0.042 | 0.363 | 0.020 | 0.629 | 0.022 | 0.349 |

| β4 | Net income -> Acquis. | 0.122⁎⁎ | 0.008 | 0.038 | 0.357 | 0.084 | 1.276 |

| β5 | Net income -> Usage | 0.028 | 0.560 | 0.026 | 0.549 | 0.002 | 0.031 |

| β6 | Net income -> Disposal | 0.056 | 0.229 | −0.022 | 0.596 | 0.078 | 1.183 |

| Goodness of fit | IFI = 0.924RMSEA = 0.065 | IFI = 0.909RMSEA = 0.076 | |||||

SEM model results by respondents’ education level.

| Param. | Relation | Primary and Middle | Secondary and Tertiary | Diff. | T stat. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||||

| α1 | ATSC -> Acquisition | 0.752 | <0.001 | 0.757 | <0.001 | −0.005 | −0.119 |

| α2 | ATSC -> Usage | 0.587 | <0.001 | 0.517 | <0.001 | 0.070 | 1.129 |

| α3 | ATSC -> Disposal | 0.599 | <0.001 | 0.586 | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.189 |

| β1 | Net income -> CC | 0.110⁎⁎ | 0.021 | −0.052 | 0.195 | 0.162 | 2.368* |

| β2 | Net income -> SMSPS | 0.164⁎⁎ | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.516 | 0.138 | 2.109* |

| β3 | Net income -> RISC | 0.104⁎⁎ | 0.030 | −0.017 | 0.675 | 0.121 | 1.890 |

| β4 | Net income -> Acquis. | 0.153⁎⁎ | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.583 | 0.131 | 1.955 |

| β5 | Net income -> Usage | 0.042 | 0.409 | 0.003 | 0.942 | 0.039 | 0.587 |

| β6 | Net income -> Disposal | 0.128⁎⁎ | 0.008 | −0.060 | 0.144 | 0.188 | 2.760* |

| Goodness of fit | IFI = 0.900RMSEA = 0.074 | IFI = 0.925RMSEA = 0.068 | |||||

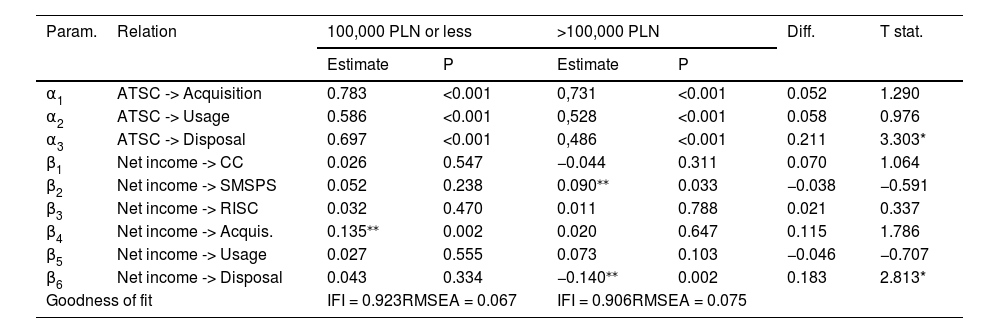

SEM model results by respondents’ assets.

| Param. | Relation | 100,000 PLN or less | >100,000 PLN | Diff. | T stat. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | P | Estimate | P | ||||

| α1 | ATSC -> Acquisition | 0.783 | <0.001 | 0,731 | <0.001 | 0.052 | 1.290 |

| α2 | ATSC -> Usage | 0.586 | <0.001 | 0,528 | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.976 |

| α3 | ATSC -> Disposal | 0.697 | <0.001 | 0,486 | <0.001 | 0.211 | 3.303* |

| β1 | Net income -> CC | 0.026 | 0.547 | −0.044 | 0.311 | 0.070 | 1.064 |

| β2 | Net income -> SMSPS | 0.052 | 0.238 | 0.090⁎⁎ | 0.033 | −0.038 | −0.591 |

| β3 | Net income -> RISC | 0.032 | 0.470 | 0.011 | 0.788 | 0.021 | 0.337 |

| β4 | Net income -> Acquis. | 0.135⁎⁎ | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.647 | 0.115 | 1.786 |

| β5 | Net income -> Usage | 0.027 | 0.555 | 0.073 | 0.103 | −0.046 | −0.707 |

| β6 | Net income -> Disposal | 0.043 | 0.334 | −0.140⁎⁎ | 0.002 | 0.183 | 2.813* |

| Goodness of fit | IFI = 0.923RMSEA = 0.067 | IFI = 0.906RMSEA = 0.075 | |||||

No significant differences were observed in relations between ATSC and analysed consumption behaviours in either group of respondents, but their sensitivity to the changes in achieved net income was not the same (Table 6). The impact of income earned on both acceptance for spending more on sustainable products and services (β2) and sustainable acquisitions (β4) was significant only for men. For both parameters, the differences in estimated values were not significant (T statistic < 1.96), but more important for the study of disparity is whether the parameter itself was statistically relevant. If the parameters in both groups were significant, then the T-statistic to investigate differences between influence strengths would be considered.

Furthermore, in that group of respondents (men), net income effects also affected the disposal of needless goods (β6 = 0.095) and awareness of consumption consequences (β1 = 0.109) significantly. The goodness of fit of estimated SEM models for both groups of respondents was correct: IFI > 0.85) and RMSEA <0.08.

In the group of respondents <44 years old, the impact of attitude toward sustainable consumption on the acquisition and usage of products or services according to sustainable consumption was significantly stronger (α1 and α2) based on T-statistic values (higher than 1.96). Furthermore, in the group of younger respondents: if they earn more, they also more often acquire sustainably (β4 is significant only in that group of surveyed). In the group of respondents, 44 years or more achieved net income only impacts their acceptance to spend more (β2), but not for the real acquisition process (Table 7). The goodness of fit of the estimated SEM models for both groups of respondents was confirmed: IFI > 0.85 and RMSEA <0.08.

The differences in education level did not indicate significant disparities in relations between ATSC and analysed consumption behaviours in either group (Table 8). Only in respondents with primary or middle education levels was the impact of achieved net income crucial for their attitude toward sustainable consumption and sustainable consumption behaviours in almost all analysed aspects. If they earn more, they also have more ATSC and buy or dispose of goods sustainably. In this group, only the relationship between net income and usage was nonsignificant (β5). The IFI > 0.85 and RMSEA <0.08 indicators for estimated SEM models in both groups confirm their goodness of fit.

The impact of ATSC on the disposal process was significantly stronger among respondents who owned less asset value (α3). Furthermore, in this group of respondents (≤100,000 PLN), if they earn more, they also spend more on the acquisition of sustainable products and services (β4 was significant only in that group of surveyed). In the group of respondents who owned assets valued >100,000 PLN, net income influenced only their acceptance to spend more (β2) but not the acquisition process (Table 9). However, the most notable between-group difference was found in the relationship between net income and disposal of unnecessary goods (β6). For the respondents who owned >100,000 PLN assets, if they earned more, they also rarely disposed of goods according to sustainable consumption (β6 = −0.140 in this group). The goodness of fit of estimated SEM models for both groups of respondents was correct: IFI > 0.85 and RMSEA <0.08.

5Robustness checkWe further verified the results using a bootstrap procedure despite the correct statistics confirming the model's quality. A bootstrap procedure based on 5000 samples from 1200 observations was employed to re-estimate the model parameters with the maximum likelihood estimator. Bootstrap allowed us to calculate the biases’ estimation bias and standard errors and determine the bias-corrected confidence intervals of 95 % (Byrne, 2010). Table 10 summarises the results of the bootstrap procedure for the internal SEM model.

Results of SEM estimation using the bootstrap.

| Parameter | Estimate | Bias | S.E. Bias | Lower | Upper | p-value |

| α1 | 0.758* | −0.001 | <0.001 | 0.717 | 0.796 | <0.001 |

| α2 | 0.542* | −0.001 | <0.001 | 0.482 | 0.600 | <0.001 |

| α3 | 0.599* | −0.001 | <0.001 | 0.531 | 0.661 | <0.001 |

| β1 | 0.021 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.044 | 0.088 | 0.530 |

| β2 | 0.083* | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 0.147 | 0.011 |

| β3 | 0.035 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.025 | 0.098 | 0.269 |

| β4 | 0.079* | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.143 | 0.019 |

| β5 | 0.017 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.049 | 0.078 | 0.621 |

| β6 | 0.025 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.041 | 0.091 | 0.458 |

For all parameters that were significant in the maximum likelihood method (α1, α2, α3, β2, and β4) 95 % confidence interval does not include 0 value, so they are also statistically relevant according to the bootstrap procedure. Therefore, the maximum likelihood–estimated models verified with bootstrap allow reliable inference based on the models.

6Discussion and conclusionsWe analysed the effects of ATSC and sustainable behaviours, with income as the control variable, and gender, age, asset, and educational level as moderators. Given the scarcity of research on sustainable consumption and attitudes towards that phenomenon using the whole approach, we included three dimensions of ATSC and acquisition, usage, and disposal as three stages of sustainable consumption. We did not limit our analysis to any one sector, stage of consumption, or consumer group. Given the scarcity of research on sustainable consumption and attitudes towards that phenomenon on the whole rather than analysis of a specific area, this study fills a gap.

We first explored the constructs of ATSC and sustainable behaviours. The results of EFA implied including consumption consequences awareness, the real impact of sustainable consumption feeling, and spending more for sustainable products and services willingness into the ATSC construct. The results align with the TPB, the SCT, and the attribution theory (Bandura, 1986; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Heider, 1958; Weiner, 1985). Additionally, elements such as beliefs about consequences, reliability of real impact, and willingness to spend more on sustainable products are analysed in the literature in the context of sustainability (Akkaya, 2021; Auger et al., 2003; Esmaeilpour & Bahmiary, 2017; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). As a result of EFA, three stages of sustainable consumption were included as sustainable behaviours. Covering the three stages of consumption is coherent with the SCB cube model and approach used by researchers (Geiger et al., 2018; Lim, 2017).

Our da revealed that ATSC was positively associated with sustainable behaviours—both overall and each stage of sustainable consumption: acquisition, usage, and disposal. Therefore, H1 was supported. These findings indicate that consumers with a positive attitude towards sustainable behaviours acquire, use, and dispose of products sustainably. Our results are in line with those of previous studies (Ahamad & Ariffin, 2018; Esmaeilpour & Bahmiary, 2017; Razzaq et al., 2018) and the TPB. Together, these results indicate that attempts to create a positive ATSC are desired and impact sustainable practices. This encourages the effective promotion of the real impact of individual decisions, the severity of the consumption consequences, and spending more on sustainable products and services to achieve sustainable consumption behaviours and, consequently, sustainable development (Lubk, 2017).

We also analysed personal income as a control variable of ATSC dimensions and particular sustainable behaviours. We identified that net income positively influences acceptance of spending more money on sustainable products and services as one of three dimensions of attitude towards sustainable behaviour. This proves that wealthier people can donate more. However, we indicated that acquiring is influenced by income. Notably, practices such as buying certificated products and services belonging to the acquisition stage of consumption are usually more expensive than buying regular products or services. In turn, practices, such as sharing, borrowing, repairing, and segregating, are more time consuming. These activities belonging to sustainable consumption's usage and disposal stage were not significantly influenced by income. It justifies analysing sustainable behaviours at different stages to capture differences between expensive sustainable practices and those that are only time consuming. It takes special significance when promotional and educational campaigns are undertaken, primarily emphasising various sustainable behaviours and increasing the knowledge about practices that are not expensive but require only involvement. Education and promotion are consistent with target 12.8 of the SDGs, according to which education for sustainable development should be included in national education policies, curricula, teacher education, and student assessment. Our results are consistent with findings about the positive association between income and sustainable attitudes and behaviours (Franzen & Vogl, 2013; Kim & Wolinsky-Nahmias, 2014; Starr, 2009). Thus, H2 was supported, stating that income significantly determines the dimensions of ATSC and sustainable behaviours.

We identified significant differences between the consumer groups. When awareness of sustainable consumption and the three stages of consumption are included, age and assets significantly diversify the relationship. In the case of age, the association between attitude towards sustainable consumption and acquisition and usage is significantly different. According to our findings, the impact of awareness towards sustainable consumption on the mentioned two consumption stages is stronger for the younger group. This link is opposite to the positive relationship between age and forms of sustainable consumption (Diamantopoulos et al., 2003; Jain & Kaur, 2006; Starr, 2009). If respondents’ assets are included, the association between awareness towards sustainable consumption and the disposal stage differs considerably between groups. In the less affluent group, the attitude more robust corresponds with disposal in reference to the more affluent group. Notably, the disposal stage of consumption included practices such as avoiding throwing away, using as long as possible, repairing, and segregating. In other words, these practises require more commitment than financial resources. Studies such as those by Lo (2016) and Roberts (1996) indicate that consciousness and sustainable behaviours may be negatively associated with income.

When income was included, between-group differences were not significant in case of significant parameters in subgroups. However, we identified significant relationships in particular subgroups. Recognised relations between income and the dimension of awareness towards sustainable consumption and sustainable behaviours were, in almost all cases, positive, consistent with the literature (Franzen & Vogl, 2013; Starr, 2009). According to our findings, the awareness of consumption consequences is significantly influenced by income for men and less educated consumers. In turn, income significantly impacts acceptance of spending more on sustainable products in the group of men, older consumers, less educated, and wealthier. When the relationship between income and the reliability of the real impact on sustainable consumption is analysed, a significant influence was identified in the case of a less educated group. Among men, younger, less educated, and less affluent, we identified that income determines the acquisition stage of consumption. Notably, we did not find a significant relationship between income and usage stage by analysing gender, age, education level, and respondents’ assets. In the case of disposal, a significant link was observed among men, less educated, and more affluent groups. Among more affluent respondents, we observed a negative impact of income on disposal. Therefore, in the group of wealthier people, an increase in income determines less sustainable disposal practices. Thus, H3 was supported: gender, age, property ownership, and education level were noted to influence the strength of the relationship between income, ATSC, and its dimensions or particular sustainable behaviours.

Our findings elucidate the effects of ATSC and sustainable behaviours, with special consideration of income determinants and different consumer groups. Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, this survey could be replicated in multiple geographic locations in future studies to formulate broader conclusions. Additionally, more characteristics that enable extracting groups would be applied, for example, beyond socioeconomic and behavioural elements. Fig. 1