The environmental, economic, and social impact of food value chains have attracted the attention of a wide range of stakeholders. However, only a few studies have focused on sustainability in the food industry in terms of social responsibility from a developing country perspective. Indeed, existing analysis has not adequately addressed the role of social responsibility on consumers’ preferences and purchasing decision. This paper intends to shed light on this nexus through qualitative research relying on in-depth interviews with decision-makers along the food value chain. Results suggest that consumers are sensitive to social abuse practices, but they face difficulties to access information in order to inform their decisions. Therefore, a higher investment in transparency instead of certifications is recommendable, as sometimes companies could be considered greenwashing. In this regard a number of opinion leaders, including retailers and wholesalers, unions, media, and governments, can play a key role to enhance awareness through information flows.

Modern food value chains (FVC) are comprised of complex sequences of resource-intensive operations, requiring workforce, financial and natural resources worldwide, which have strong social, economic, and environmental implications (FAO, 2017). Indeed, many food producing countries face serious human and labor rights problems (Higonnet, Bellantonio, & Hurowitz, 2017; Leiter & Harding, 2004), where the national economy is relatively weak and prices are volatile (Wessel & Quist-Wessel, 2015). In a scenario of increasing globalization, corporate social responsibility (CSR) can play a more significant role (Toussaint, Cabanelas, & Blanco-González, 2020).

While there is not an official definition (Eyasu & Endale, 2020; Morgan, Widmar, Wilcoxc, & Croney, 2018), the European Commission (2001) described CSR as “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis”. In 2011, the European Commission proposed a new definition where CSR is “the responsibility of enterprise for their impacts on society”. In the food industry, CSR has become increasingly important due to the interest of stakeholders in food production, and its impacts on the environment and society (Hartmann, 2011). In fact, many CSR studies have focused on environmental issues, such as environmental activism (Devinney, Auger, Eckhardt, & Birtchnell, 2006), the use of recycled materials and packaging (Auger, Devinney, & Louviere, 2007), impacts of food production (Lusk & Briggeman, 2009). In parallel, consumers are becoming more aware of the consequences of their purchasing decisions in terms of environmental and social sustainability (Grunert, 2011; Mohr & Webb, 2005; Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006). Faced with an information deficit, consumers value CSR as they feel better when they buy products from brands associated with socially responsible behaviors (Arvola et al., 2008; Brown & Dacin, 1997; Poortinga, Steg, & Vlek, 2004). This perspective is also reflected on consumers’ behavior literature when studying the relationship between consumers’ ethical behaviors and their willingness to pay (De Pelsmacker, Driesen, & Rayp, 2005), organic food products (Jitrawang & Krairit, 2019), food labels and urban consumers (Kaczorowska, Rejman, Halicka, Szczebylo, & Gorska-Warsewicz, 2019), among others.

However, a review of the current literature reveals a number of biases and deficits. First, the research on social issues within CSR are normally associated to safe food, food safety, environmental protection, and ensuring access to natural resources for future generations (Lamberti & Lettieri, 2009). Only a limited number of studies have focused on CSR regarding transparency and social responsibility in terms of social issues (Bhaduri & Ha-Brookshire, 2011; Kang & Hustvedt, 2014); particularly the analysis of core concepts of social responsibility along FVCs has not been subject of study (Toussaint et al., 2020).

Second, most studies analyzing CSR in the food sector are from a developed country perspective (Diddi & Niehm, 2017; Jitrawang & Krairit, 2019; Morgan et al., 2018), lacking the developing country perspective in order to be more inclusive in understanding the overall issue. This is a major point because FVCs are organized globally.

Third, the extent to which the social component of CSR influences consumers’ preferences is less understood, especially in the food and agriculture sector (Morgan et al., 2018). Despite concerns about human labor, social issues are becoming more relevant for consumers in developed countries; there is more awareness of the well-being and care of livestock animals in food production (Croney & Botheras, 2010). It becomes contradictory with Auger et al. (2007) findings, which suggest that social and ethical issues – i.e. labor and human rights- are consistently chosen as more important than other issues, regardless of the nationality.

This paper is based on different theories, particularly the Institutional, Legitimacy and Stakeholder theories (Mani & Gunasekaran, 2018; Toussaint et al., 2020). These theories help to understand why companies decide to adopt social sustainability criteria adopted by societies (Mani, Gunasekaran, & Delgado, 2018). It favors social conformity (Deegan, 2001). Social practices are a response to an exogenous pressure that sometimes is not internalized in the company. However, it has facilitated the appearance of greenwashing or window dressing activities by firms (De Jong, Harkink, & Barth, 2018). Greenwashing means that a company is making a false impression or providing misleading about environmental issues. In so doing, a company can appear to act responsibly while behaving without responsibility (Aji & Sutikno, 2015). If customers are aware of social issues, it can have its subsequent effects on brand equity and in the purchase intentions (Akturan, 2018).

A way to mitigate this weakness is resorting to the application of stakeholder theory, an approach not often applied in institutionalism (Gimenez & Tachizawa, 2012), and that provides an interesting control on CSR related activities. In this case, social issues, taking this approach means integrating multiple perspectives which can complicate analysis, but undoubtedly it enriches it. Again, such an analysis deepens understanding of the process as it incorporates intangible activities related to competitive strategies but can foster learning and the development of capabilities for the company and the whole value chain (Cabanelas-Lorenzo, Cabanelas-Omil, & González-Vázquez, 2008; Cabanelas, Omil, & Vázquez, 2013).

Through a dialog with policy makers and corporate strategists, this study aims at exploring the consumers’ behavior when purchasing food products, and the influence over such decisions of companies’ social practices within their CSR. It becomes an important issue from a theoretical perspective in terms of ethics and decision-making processes, due to the complexity of possible relationships between variables not yet identified or studied, making it challenging for other behavioral studies (Malhotra & Miller, 1998). This study applies exploratory and qualitative methods to its analysis based on the Grounded Theory (GT) analysis (Johnson, 2015). The study combines desk research with input from a panel of 19 high level decision-makers who are involved on sustainable development, CSR, and the food value chains. Given that the stakeholder perspective is often lacking in the existing literature, this paper can provide the basis for further studies targeting consumers.

As a first step it is relevant to collect and analyze information from decision-makers because their position and their experience allow them to understand consumer trends from an aggregated and global rather than an individual perspective. Also, the information extracted from interviews offers a global conception about consumers’ behavior in terms of preferences and attitudes. Results from these interviews can then be incorporated into future research to include the individual approach as a final consumer. Results aspire to reduce the gap regarding CSR in FVCs from a consumers’ purchasing decision (CPD), making the concept more inclusive in terms of social aspects.

This paper is structured as follows. The second section reviews the literature, including relevant concepts on this topic. The third details the methodology providing an explanation of the research approach. Later, the findings are described, including a discussion about the results obtained. Finally, the study finishes with conclusions integrating the main theoretical and practical implications, and the limitations and future directions of research.

2Literature review2.1CSR strategy and FVCsTransnational companies usually relocate their products within their value chain to third countries where the lack of protection of human and labor rights takes place, thus those companies generate more profit by reducing workforce costs (Prasad & Holzinger, 2013). Most food products are thus harvested in developing countries, where these situations occur (Higonnet et al., 2017; Leiter & Harding, 2004), mainly in the first steps of the FVC as the institutional environment and national enforcement are weak. Hence, the CSR and considerations of human rights are not likely to come into play until much further down the FVC (Toussaint et al., 2020). It is therefore the importance of applying the triple bottom line concept – i.e. economic, social and environmental sustainability (Elkington, 1998) – into the CSR as a requisite to avoid supply chains that only apply a “green” approach (Pagell & Shevchenko, 2014). Not only that, another problem related to employment is food fraud. As a globalized industry, food industry supply chains are complex. Thus, companies have less visibility and control of relevant stages of the value chain, and monitoring agencies have less capacity to detect fraudulent incidents. Rocchi, Romano, Sadiddin, and Stefani (2020) analyze the correlation between employment and fraud practices, particularly in agri-food products, where employment is directly and indirectly affected by this.

As part of CSR strategies, companies have engaged to ameliorate social and environmental impacts of their own activities (Dauvergne & Lister, 2012; Vogel, 2010), where in the last two decades food retailers and manufacturers have begun to commit deeply. These commitments focused particularly on environmental issues in their supply chains (Beghin, Maertens, & Swinnen, 2015; Lemos & Agrawal, 2006; Newell, Pattberg, & Schroeder, 2012; Waldman & Kerr, 2014). Managers decided to apply private certification schemes to accomplish food standards set by certification bodies linked to food safety and environmental issues, (Manning, Baines, & Chadd, 2006; Trienekens, Wognum, Beulens, & van der Vorst, 2012; von Geibler, 2013), rather than improving workers’ conditions or farmers’ livelihoods. Indeed, only a few scholars have analyzed specific activities of the food industry, e.g. palm oil (McCarthy, Gillespie, & Zen, 2012; von Geibler, 2013), chocolate (García-Herrero, De Menna, & Vittuari, 2019), black soybean and tomato (Sjauw-Koen-Fa, Blok, & Omta, 2018).

Although some CSR studies investigate developing countries in the food industry, social problems related to working conditions in the entire FVCs have not been addressed (Toussaint et al., 2020). In addition, CSR research has been focused on consumers’ behavior, food safety and sustainability issues, particularly linked to the environmental performance (Glover, Champion, Daniels, & Dainty, 2014; Zhu et al., 2018). However, there have been cases where a company's image and reputation were damaged due to unsustainable practices (Bhaduri & Ha-Brookshire, 2011). Therefore, consumers are becoming more interested about a company's overall corporate performance before decision-taking (Lee, 2020).

2.2CSR, brand value and CPD in the FVCCSR is considered by many businesses as a central element on brand differentiation policies (Hildebrand, Sen, & Bhattacharya, 2011; Maignan, Ferrell, & Ferrell, 2005). Managers tend to adopt social and environmental initiatives to differentiate their brands in a highly competitive marketplace (Boccia, Manzo, & Covino, 2019). Decision-makers are thus implementing branding strategies going from the product-level to communicating values and building a socially responsible brand (Golob & Podnar, 2019).

Ramesh, Saha, Goswami, Sekar and Dahiya (2019) have demonstrated that CSR initiatives strengthen brand image and consumers’ attitude toward the brand. At the same time, the company's reputation will be affected by the perception of its relevant actors linked to its activity and final consumers (Keh & Xie, 2009). So, having a positive reputation, a company becomes more attractive and trustworthy and economic benefits accrue (Walker, 2010). Although, stakeholders are key actors for companies, as they are becoming more informed about the CSR company's practices and activities (Moure, 2019). Hence, if a CSR of a company is intended to be used as a whitewashing strategy, this can be counterproductive for the company.

Therefore, sustainable and responsible products are getting more attention. Particularly, consumers from developed countries are considering the environmental and social impacts of companies’ actions (Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006). CSR studies and its influence on CPD have been conducted in several industries including organic food, health, apparel, energy, and water (Arvola et al., 2008; Dodd & Supa, 2011; Godin, Conner, & Sheeran, 2005). Scholars have shown a positive relationship between a company's CSR activities and CPD toward that company and its products (Lacey & Kennett-Hensel, 2010; Lii & Lee, 2012).

Specifically, the CPD depends on the level of consumers’ interest and information available to that consumer (Muruganantham & Bhakat, 2013; Schmitz, Lee, & Lilien, 2014; Shankar et al., 2016). Although consumers make numerous food decisions every day, food products are characterized by repetitive purchase behavior (Wansink & Sobal, 2007). Even though there are several private food certifications in order to promote sustainable food products by adding a label on a product, those labels are not fully understood by consumers, nor even create credibility or certainty whether a product is sustainably harvested or produced (Kaczorowska et al., 2019).

In summary, despite the fact that there are several studies analyzing the influence of CSR on consumers’ decisions and behavior – e.g. food choices among peers (Edenbrandt, Gamborg, & Thorsen, 2019), consumers’ intentions (Diddi & Niehm, 2017), including effects of CSR on consumers (Lacey & Kennett-Hensel, 2010), there is no study analyzing the relationship between food brands and the consumer per se. Furthermore, there is no study analyzing the CPD in relation with CSR and the brand value, addressing social implications in the food industry rather than the environmental ones. Considering the essential part food plays in our daily lives filling this gap would seem important.

3MethodsThe research follows an explanatory and qualitative approach to understand and analyze the role of CSR in FVCs and its relationship with final consumers. This study uses the Grounded Theory (GT), a common method applied for empirical analysis in social sciences (Cabanelas, Manfredi, González-Sánchez, & Lampón, 2020; Johnson, 2015). This approach allows the generation of new theories or conceptual propositions from data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987) by offering a logically-consistent set of data collection and analysis procedures aimed to develop theory (Charmaz, 2001: 245). Following the three basic elements of GT: concepts, categories, and propositions (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). According to Corbin and Strauss (1990, p. 7), the first element “concepts” refers to the basic units of analysis that comes from the data conceptualization, but it is not the actual data per se. The second, “categories” is more abstract than the “concepts” and becomes the cornerstone of theory development as it provides the meaning whereby theory can be integrated. Finally, “theory” provides the propositions, which suggest generalizable relationships between a category and its concepts, and between discrete categories. Originally, Glaser and Strauss (1967) called this element “hypotheses”.

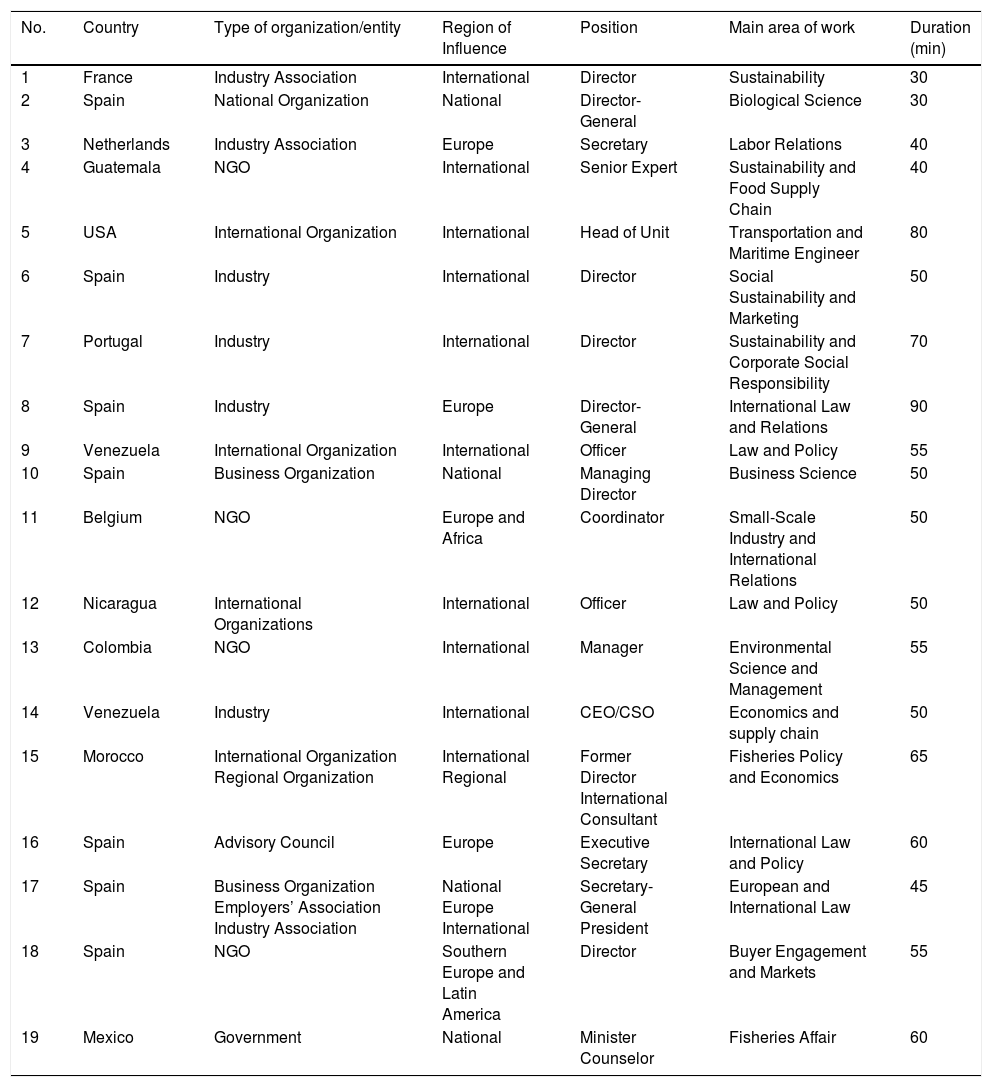

3.1Sampling and data collectionThis study conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews (Minten, Tamru, Engida, & Kuma, 2016) with open-ended questions, aiming to collect technical and practical information about social sustainability along the FVCs from a consumers’ perspective. The fieldwork and the further analysis include data and information from nineteen semi-structured interviews (Table 1). The sample selection was designated carefully based on their experience in relation with social responsibility, FVCs and social sustainability, as well as their job positions and professional career. Most interviewees are high-level representatives working in an international and national environment, in public and private entities. The breadth of the sample size was a key element for this paper as the focus is a holistic approach to understand trends and decisions in FVCs. The sample is fundamental for this study, as it is inclusive considering relevant stakeholders in FVCs.

Information of the interviewees.

| No. | Country | Type of organization/entity | Region of Influence | Position | Main area of work | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | Industry Association | International | Director | Sustainability | 30 |

| 2 | Spain | National Organization | National | Director-General | Biological Science | 30 |

| 3 | Netherlands | Industry Association | Europe | Secretary | Labor Relations | 40 |

| 4 | Guatemala | NGO | International | Senior Expert | Sustainability and Food Supply Chain | 40 |

| 5 | USA | International Organization | International | Head of Unit | Transportation and Maritime Engineer | 80 |

| 6 | Spain | Industry | International | Director | Social Sustainability and Marketing | 50 |

| 7 | Portugal | Industry | International | Director | Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility | 70 |

| 8 | Spain | Industry | Europe | Director-General | International Law and Relations | 90 |

| 9 | Venezuela | International Organization | International | Officer | Law and Policy | 55 |

| 10 | Spain | Business Organization | National | Managing Director | Business Science | 50 |

| 11 | Belgium | NGO | Europe and Africa | Coordinator | Small-Scale Industry and International Relations | 50 |

| 12 | Nicaragua | International Organizations | International | Officer | Law and Policy | 50 |

| 13 | Colombia | NGO | International | Manager | Environmental Science and Management | 55 |

| 14 | Venezuela | Industry | International | CEO/CSO | Economics and supply chain | 50 |

| 15 | Morocco | International Organization Regional Organization | International Regional | Former Director International Consultant | Fisheries Policy and Economics | 65 |

| 16 | Spain | Advisory Council | Europe | Executive Secretary | International Law and Policy | 60 |

| 17 | Spain | Business Organization Employers’ Association Industry Association | National Europe International | Secretary-General President | European and International Law | 45 |

| 18 | Spain | NGO | Southern Europe and Latin America | Director | Buyer Engagement and Markets | 55 |

| 19 | Mexico | Government | National | Minister Counselor | Fisheries Affair | 60 |

The interviews were conducted face-to-face and telematics from September to December 2019. Due to the lack of analysis on this topic, the sample selection is judgmental and composed by people working closely on social sustainability, value chains and sustainable food. This sample will help to analyze the level of knowledge and awareness of this topic. The diversity of the sample helped generate new insights regarding consumers’ behavior and decisions, examples of products made under deficient social responsibility guidelines, comparing and analyzing food products, possible solutions and who are the prescribers.1 Before conducting the interviews, it was agreed with interviewees an ex-ante anonymity to make them free to answer all the questions without compromising their positions and the organization or entity. All interviews were recorded with the proper authorization from each interviewee for its further analysis in order to provide the main source of information of this research. The comments were transcribed verbatim to avoid any lack of clarity making these transcriptions. To obtain maximum neutrality, this study considered all the point of views obtained from the content analysis in the conclusion. The main elements of the script intend to bring more clarity to understand CPD and behaviors on food products (in Appendix I the complete questions):

- •

The relevance and effect of CSR on final consumers.

- •

Analysis of CPD and behavior concerning products made under bad working conditions.

- •

Identifying food products, its relationship with consumers and with the brand.

- •

How to mitigate those bad practices and how are the prescribers of good practices.

This study used a qualitative tool for data analysis by using codes, relations, and annotating activities (Cabanelas et al., 2020; Johnson, 2015). The software Atlas.ti© was used for the content analysis where first participants’ quotations were coded using in vivo codes to analyze the data and develop codes based upon participants’ language (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). The codes into first-order themes reflective of the component code elements by using common threads connecting the initial codes (Johnson, 2015). Subsequently, it was axially coded these first-order categories to build the emergent framework of the findings (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Then, the selection of codes to unify the core categories, which need further explanation. Finally, the analysis concludes with the exhibition of the results in an extensive narrative form (Johnson, 2015).

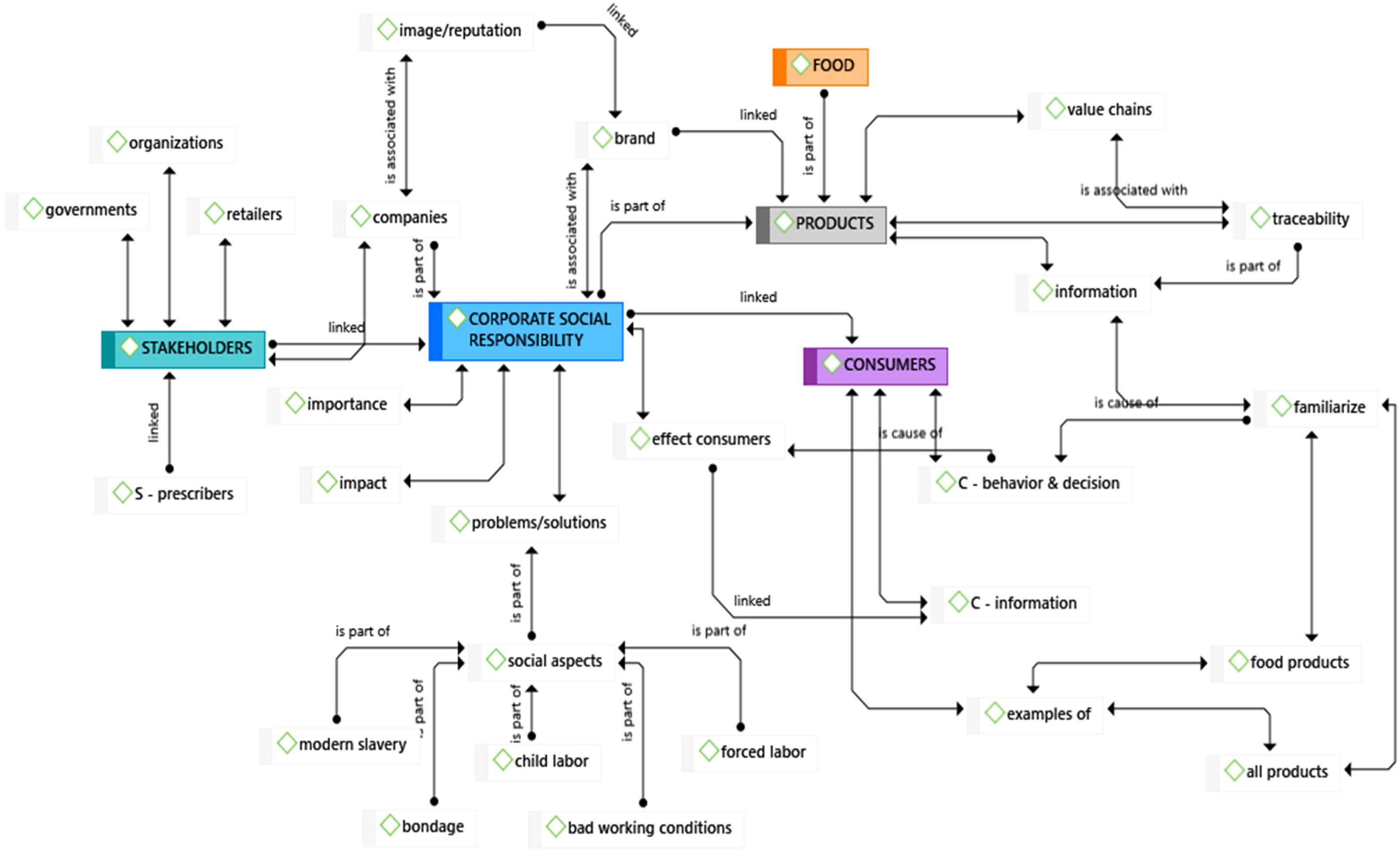

In this regard, this paper transcribed the nineteen semi-structured interviews and uploaded in the software to facilitate the analysis. While analyzing the transcriptions, codes were created based on interviewees’ language and the repetition of those keywords (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), such as social responsibility, social sustainability, CSR, consumers, value chains. Once having created the codes, first-order categories were established, which are the elements that compose one particular code (Johnson, 2015). In the case of CSR, Fig. 3 (Appendix II) shows the first-order categories. Then, after the analysis of the information, networks were created to enable understanding by providing linkages among the codes. During the analysis, memos were used as a support tool to keep relevant information.

4ResultsThis section provides a deeper understanding of CSR strategies on consumers. Fig. 1 reflects the interrelations among the main concepts identified during interviews that helps guiding this section. With this aim, results start exploring the importance and effect of CSR and how it influences the consumers’ insights from the managers’ perspective; it permitted a deeper understanding of those weaknesses on CSR implementation. Next, it assesses CPD regarding products made under situations where human and labor rights are being violated. Then, it refers to the specificities of food products compared to other products to evaluate consumers’ awareness of the main problems and its brand. Finally, it identifies mitigation measures to improve bad social practices in FVCs and to identify the opinion leaders from the consumers’ view.

Fig. 1 shows the main elements that influence CSR, which should be considered when referring to social sustainability in FVCs. CSR has an impact on consumers, mainly in their behavior and decisions. Thus, products produced by companies with CSR could have an influence on CPD. Moreover, serious problems such as child labor, modern slavery, forced labor, bondage and bad working conditions appeared during the interviews to raise awareness and tackle those situations. Also, there are companies addressing these issues within their CSR plus other social issues – i.e. gender balance, trainings, decent working conditions, among others. In order to achieve the main objective of this paper, the analysis highlights the main problems along the FVCs. In addition, Fig. 4 (Appendix III) provides a complete outlook of the interlinkages among codes and categories extracted from the analysis.

4.1CSR's influence on final consumersConsumers play a key role in the results of CSR as they have the power of buying a product. Through commercial preference and consumption, people are reflecting the type of society they want ought to live in. Although the problem is that they do not usually have adequate information to make an informed purchasing decision. It is thus important to create consumers’ awareness about the conditions of production regarding social issues where humans are involved: Consumers cannot guess what was behind the production of the product they want to buy.

Consumers choose products based on a variety of factors although price is often highly important (e.g. clothes, food, furniture, etc.). Therefore, it exists a need to change the system. It is important to make the right balance between the real price and the product. Educating the consumer on the real price of a product will require a change in the system of purchasing. However, if the final price is more expensive, consumers may not be able to afford these products. This occurs because there are consumers that cannot, even if they want to buy sustainable products, because they have other priorities and/or obligations where to spend their money.

Certainly, consumers expect that the products offered are safe and wholesome, respecting the environment and the people who made or produced them. They are sensitive to big scandals, as it has happened with environmental issues. Currently, people are focusing more on environmental issues, where NGOs have pushed retailers and wholesalers to change their operations and requirements to buy environmentally sustainable products. Meanwhile, there are a lot of food products where situations of slavery, child forced labor, and other type of abuses are taking place. Retailers and wholesalers might know about this situation and most of the time they still prefer to buy products at a lower price as long as it does not affect the retailers and wholesalers’ image or reputation. In addition, there is a relationship between the consumer and the supermarket, where the consumer trusts that a specific supermarket buys its products responsibly: The normal consumer goes into the supermarket and expects everything to be correct, even if they see the same products with different prices elsewhere. Consumers do not have to question themselves.

Therefore, if a consumer learns that a food product is made under situations that are not humane such as slavery, that consumer is likely to stop buying the product. This will have an impact on consumers, hence, the importance of raising awareness on these situations within FVCs. Some companies mislead consumers by saying that they have responsible and sustainable initiatives when they do not. Also, having a logo does not guarantee that human and labor rights are being respected. Thus, the next proposition comes up:

P1. Although CPD is influenced by multiple factors (i.e. income), the consumers are interested on receiving information about how a product was made to make a conscious decision.

4.2CPD and behavior concerning bad social practicesWhile asking interviewees about situations, such as indecent working conditions or violation of labor rights, etc., to produce a product, they agree that being aware of those situations will have an influence on their purchasing behavior and decision. Many relevant aspects should be noted. Despite interviewees’ familiarity with social sustainability, working conditions, among others, they stressed that the average consumer is not even aware that situations where there is modern slavery, child labor, forced labor, bad working conditions, among others, are still happening nowadays. If people know what is really happening in the industry and aware of the reality, they may adopt more conscious purchasing habits in their daily lives: As I work on issues related to this and I am more informed, this has affected my purchasing decision. Therefore, I prefer to buy in the local market this also helps the environmental impacts.

There is a strong connection between a company's reputation and the rejection of bad social practices. If a company lacks a good CSR and its implementation, the consumers’ behavior will be affected, and as a result, consumers will stop buying from that brand, store, or retail company. Moreover, retailers, wholesalers and distributors, or companies at the end of the value chains are accomplices for offering goods produced under bad working conditions. Usually, they are aware of the origin of their products and the circumstances in which products were made. Also, consumers may question themselves about companies having lower prices and their profitability: It is not only having the power of being consumer, it is the fact that that product should not arrive at the point-of-sale. If a company has the information about those cases, then the market should have the access to that information.

The lack of transparency and information available for consumers are key issues for them to make their own choices. Interviewees noted that the available information is not enough to differentiate whether a product is produced under bad working conditions, sometimes not even its origin.

Although it is quite difficult to buy products while being responsible and at the same time thinking of sustainability, consumers are keen to incorporate good practices into their daily lives. However, due to the lack of information, this is rather challenging for consumers. Another factor is that globalization has made value chains more complex, making it more difficult to monitor and track products in the supply chains. Therefore, large companies should implement good traceability systems. This will generate reliable and clear information for consumers, demonstrating their treatment to employees and social issues while taking into consideration their outsourcing partners (and their operations in terms of social and labor issues), because some large companies prefer to outsource seeking a cost reduction and selling products with unfair prices.

Subsequently,

P2. The reputation of the company influences CPD as customers are sensitive of human abuses. The FVC should provide accurate and reliable information about the traceability of their products to facilitate consumers decision-making.

4.3Food products and the relationships with the brandInterviewees easily identify products developed under bad conditions and working abuses (lacking good social practices): clothes, sport clothing and accessories, and technological devices as mobiles and computers. Most social problems are identified in developing countries, where law enforcement, conditions and capacity are weak; however, it also happens in developed countries but in a different context. While asking for products under these circumstances, interviewees were able to identify the brand with their bad practices providing examples about the product and the context: When there was a big scandal of a certain sports brand regarding workers abuses and bad working conditions, despite after that brand improved its practices, for me its reputation changed. If that brand was able to take advantage of that situation and of those vulnerable people, it is enough for me to reject that brand.

It was acknowledged that information is important to provide an overview of the reality, however, most consumers are not aware of this. Nevertheless, interviewees can identify the products above-mentioned due to the influence that the media has played. This means that consumers changed their purchasing behavior and decision-making because they were aware of those bad practices from companies. Although, it was noted that it is important to be careful with the information that the media published as sometimes could be biased publicity.

While referring to food products, interviewees recognize the agriculture industry – including fisheries – as the one affected by the lack of social issues. Therefore, within the agriculture sector, palm oil, sugar, cocoa, coffee, teas, and fish products are repeatedly mentioned. Situation of modern slavery, forced labor, child labor, bad working conditions, unsafety workspace, lack of legality regarding contracts and recruitment process, long working hours, exposed to chemical substances, abuses of any type, and human trafficking are referenced when talking about social issues in FVCs. In addition, in food products it is very difficult and complex to identify a brand since production is located, mostly in developing countries, where working conditions are not appropriate, and because FVCs are long and where many actors are involved making traceability difficult. Summarizing, the proposal is as follows:

P3. As the information on social issues in FVC is scarce, opinion leaders (i.e. media, governments, and so on) should reflect what happens in developing and developed countries in case of social abuses during food production.

4.4Mitigation measures and prescribers on social practicesTo mitigate the situations above-mentioned, what consumers can do is to stop buying a product that they are aware to be produced under intolerable circumstances. From a consumers’ perspective, they can buy from the local market and support cooperatives. Although, it was stressed that this is not the most efficient nor most effective way to address the problem, and here lies the importance of CSR: CSR should be promoted by all actors involved in the FVCs. Companies should be able to demonstrate that they are being socially responsible, giving the rights to employees, respecting them, and acting in a legal way. Companies should be transparent with their information and in the way they operate.

To improve and ensure better working conditions, the responsibility comes from all the actors along the FVCs, particularly the last actor (i.e. retailers and wholesalers) shall secure that. Interviewees emphasized that the responsibility does not fall on the final consumer as some actors within the value chain noted. Indeed, the importance of guaranteeing good social practices and decent working conditions to ensuring human and labor rights along the entire value chain requires the involvement of all actors. Every actor along the chain should be responsible for their actions. In this way, if all actors are responsible this will be extended throughout the entire value chain up to its origin ensuring decent working conditions. To accomplish this outcome, there is a need to increase transparency and to improve traceability. Companies should provide clear information about their products, their processes and origin. Furthermore, if a company is not acting responsible, here is where the role of the media, trade unions and some NGOs is important. They could expose situations where people are working under indecent conditions is necessary to raise awareness and have an impact on people, as well as to create a reputational risk for the company selling those products while engaging in unfair competition. This will force companies to comply with national law and policies, improving their practices to protect its people: You need to push to make sure that people are protected and to be sure that laws are enforced. Otherwise it is important to expose the company which is acting unethical by violating human and labor rights.

Fig. 2 shows the word cloud results from the analysis about the responsible authorities of good social practices in FVCs. Besides companies’ responsibility, interviewees include the responsibility of governments to enforce national laws and execution. Also, governments should fight against any sort of corruption to increase transparency in their national systems. Governments should increase and improve labor inspections, to ensure that companies are fulfilling the standards related to these issues, and to have more stringent legislation to ensure workers are being protected. It reflects that governments, companies, and retailers (including wholesalers) should be the ones working toward it. This means that stakeholders should work together along the entire FVC to secure products made under socially responsible practices.

Albeit some interviewees mention consumers as the main prescribers regarding social practices in the industry because a change on their buying habits could impact the markets. It is especially important the relationship between the final retailer and consumer as retailers and wholesalers are the last actor of the value chain and they have high purchase power. Thus, they should ensure the compliance of standards and good practices along its entire supply chain. Although, retailers should not have the total power on that as they should collaborate with governments and mainly with trade unions: We cannot blame consumers for not being socially responsible. A product that is elaborated in bad working conditions and having involved human abuses should not even be offered as a final product in a store or supermarket.

It is the industry that knows what good social practices are and what should not be allowed to take place. Companies at all stages of the value chain should take a responsible attitude in order to develop good practices and call out those companies acting with unethical behavior. Companies should consider workers’ views while developing their activities. Likewise, the lack of enforcement by governments is key to ensure decent working conditions. Governments should ensure this through public policies and normativity, where companies should take the initiative to adopt those practices. In addition, governments should develop social sustainability policies to be implemented in their own national legislation. The role of international organizations is important as they can provide technical assistance and guidelines to support developing countries. The next proposal is suggested as:

P4. All actors in the FVC should ensure social responsibility, not only for consumers but for workers. The compliance of international and national policies and standards, and collaboration among stakeholders is important to work toward social responsibility in FVCs.

5Discussion5.1Theoretical implicationsThis study adds new insights to social responsibility in FVCs by including the consumers’ perspective into the analysis of policymakers and strategists. As there are many studies of CSR focused on environmental aspects (Auger et al., 2007; Devinney et al., 2006; Lusk & Briggeman, 2009), this study expands the debate by including social aspects, such as the importance of respecting human and labor rights, decent working conditions, taking into consideration of communities where companies are based, and their relationship with their business actors in their supply chains. It also provides more information about the consumers’ perception (De Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Jitrawang & Krairit, 2019; Kaczorowska et al., 2019) by including this concept as the consumers’ conception in connection with companies’ social practices in the food industry. This approach includes the cohabitation of different theories namely institutionalism, legitimacy, and stakeholders, as a pertinent approach to holistically analyze the problem that occurs in global value chains as FVCs are. This study highlights the need to analyze CSR in the food industry from a developing as well as a developed country view to fully understand the problems and challenges of these complex and global issues. Consumers are becoming more concerned about sustainable products (Arvola et al., 2008; Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006). This study provides an analysis of the possible factors that influence their purchasing decision, and that the average consumer is often not even aware of social issues along the value chain.

5.2Managerial implicationsAmong the managerial implication, first, it is interesting to highlight the need to explore more FVCs linked to CPD and CSR to improve and ensure the respect of labor rights at work. It is also important to note the complexity of addressing social issues, as there is not enough information nor even an official definition of what social sustainability encompasses. Nowadays, CSR of a company is getting more attention from the consumer side as they are becoming more aware and conscious of their purchasing decisions. Companies implement CSR to improve their reputation and their image to gain more profits, and, in some cases are greenwashing activities. ‘Greenwashing’ means that a company is making a false impression or providing misleading about environmental issues. Although there is not a term for social issues companies also apply the concept for working conditions. If a company is implementing a good CSR, it has to demonstrate those practices and communicate it through the annual report. With the inclusion of social issues of a company in the annual report will facilitate the auditing and monitoring regarding the company's activities. The company's information should be clear and transparent, and this information could be confirmed in future assessments.

Therefore, there is a strong link between the CPD and a company's image, where the CPD is predicated on corporate behavior. Most informed consumers would prefer to buy from a company (e.g. band, store, supermarket) that sells sustainable and responsible products. Although, not everything depends on the consumers’ preference because they buy a product whether they can afford it. Moreover, it should not be the consumer asking itself if a product is or not socially sustainable because it should be the last stage of the value chain to ensure that a product meets the minimum requirements in terms of sustainability. Of course, if a product is made under human abuses, rights violations and indecent working conditions consumers will not buy that product if they aware of those practices. There should be more information about these practices in the food industry to raise awareness and let people know what is happening.

However, the lack of information on social issues remains, where environmental issues have predominated over social problems. The collaboration between trade unions, some NGOs and media is important to address these problems as it happened with environmental problems worldwide. Likewise, the collaboration between governments, the industry and trade unions is important to counterbalance powers in order to take actions from both conceptual and practical perspectives. The importance of increasing traceability systems to monitor operations and activities related to who has been involved in the elaboration of a product is key, especially as FVCs are getting longer and more complex. Furthermore, the identification of food brands is hardly recognized, as well as food products made under bad working conditions. Thus, the relationship between food brands and food products is less acknowledged from the consumers’ perspective. Consumers hardly identify a food product with its brand. Moreover, consumers may change their habits to mitigate bad practices, and they can turn to local markets as well as places where they know are responsible in their operations. Although consumers have the purchasing power, the prescribers of good social practices are those actors involved in a product's chain (Cabanelas-Lorenzo et al., 2008), but particularly retailers, wholesalers and governments. Both in collaboration with trade unions, NGOs international organizations, institutions and with their business partners.

5.3Limitation and further researchFirst, one limitation of this study was that interviewees are more familiar with the industry they are working in, making it difficult to further explore other areas of the FVCs. This limited the research because it was difficult to identify specific food products outside of their sectors. Second, this study analyzes interviewees’ opinions that are familiar with this topic. It would be interesting to analyze an average consumer's behavior and decision about social issues in food products to deeply understand its implications. Third, as this research provides cross-sectorial insights and a picture in a specific moment, it would be interesting to analyze it longitudinally, as well as comparing situations in developing and developed countries. Finally, as this study takes global approaches, it would be useful to analyze the primary production where companies develop their activities in local communities and evaluate their involvement and commitments with them. Moreover, it would be interesting to analyze the interconnectivity between food products and consumers’ sensitiveness involving social issues, and their willingness to pay for those food products.

Funding sourceThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Script in-depth interview

- 1.

CSR effects on final consumers:

- •

Its relevance.

- •

What are its implications.

- •

- 2.

Consumers’ decision and behavior:

- •

Implications of being aware that a product is made under bad working conditions by not respecting human and labor rights, and not implementing international and national laws and standards.

- •

Example of products under those conditions.

- •

Comparison between food products and other products.

- •

Food products and the relationship with the brand value.

- •

- 3.

- Food products:•

Types of food products.

- •

Examples of food products made under bad working conditions.

- Food products:•

- 4.

Mitigations and prescribers:

- •

How those bad practices can be mitigated?

- •

Who could be the prescribers of good practices?

- •

Person or organization with expertise in the field that can act as consultant to describing problems and giving potential solutions (e.g. Cabanelas-Lorenzo et al., 2008; Cabanelas et al., 2013).