This study investigates board characteristics, including board leadership structure, which explain the human capital disclosure (HCD) provided by companies. It uses a self-constructed disclosure index to quantify the level of human capital information using content analysis. Generalized method of moment is employed to estimate a dynamic model of the relationship between HCD and the characteristics of boards of directors. The results show that companies are adapting to the new European Union (EU) Regulation Directive 2014/95/EU by increasing their HCD. There has been a change in the topics disclosed by companies that signal a commitment to social responsibility toward their employees and stakeholders. The level of HCD is significantly associated with board leadership structure, and independent directors play a moderating role when a chief executive officer (CEO) duality exists. Additionally, factors such as gender diversity, board size, board activity, company size and age, and the EU Directive approved in 2014 are all associated with HCD. This study enriches the debate on the role of independent directors in HCD because they can exercise a moderating role when CEO duality is present.

Human capital (HC) is considered an essential intangible resource in companies’ value-creation processes (Abeysekera, 2008; Khan & Khan, 2010; García-Zambrano et al., 2018). This reinforces the importance of concern and awareness in applying responsible and sustainable HC management practices (GRI, 2013; McCracken et al., 2018; Moussa & El Arbi, 2020; Ramírez & Tejada, 2022; Tejedo-Romero & Araújo, 2022). Some scholars, such as Abeysekera (2008), Jindal and Kumar (2012), Gamerschlag (2013), and Tejedo-Romero et al. (2017b), have pointed out the relevance of intellectual resources, such as knowledge, skills, experience, expertise, and people's abilities to drive value generation (intellectual capital perspective; IC). Others, such as Vuontisjärvi (2006), Kent and Zunker (2013), Tejedo-Romero et al. (2017b), Celma et al. (2018), Parsa et al. (2018), and Castilla-Polo and Ruiz-Rodríguez (2021), have considered the importance of companies’ ethical and responsible behaviour towards their employees, avoiding discrimination and promoting equality, participation, and employees’ learning, amongst other social issues, because these attitudes increase companies’ value and reputation, and ensure their sustainability (social responsibility perspective; SR). Employee well-being means that employees will be more satisfied and motivated, which will improve their performance and productivity (Abeysekera, 2008; Álvarez-Domínguez, 2012; Rodrigues et al., 2017; Tejedo-Romero, 2016; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2018). Hence, incorporating socially responsible and sustainable strategies into HC management can generate intangible resources and create sustainable competitive advantages (Gamerschlag, 2013).

Despite the growing relevance of HC, traditional accounting systems have lost their credibility to accurately depict an adequate picture of companies’ values because of the existence of restrictive accounting standards (Khan & Khan, 2010; Jindal & Kumar, 2012; Tejedo, 2016). Lev et al. (2012) and others have severely criticised the treatment of certain intangible resources in accounting standards, such as HC, arguing that accounting systems that do not recognise value-creating intangible resources as assets in their financial statements, fail to state the true value of companies. This is the reason for the loss of the usefulness and relevance of financial statements (Abeysekera, 2008; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021). This loss of relevance as prompted stakeholders to request that companies voluntarily disclose HC information so that they can judge company performance and value-creation processes in a complex manner. Therefore, the issue of human capital disclosure (HCD) has become a key issue for organisations, shareholders, potential investors, current and potential employees (Vuontisjärvi, 2006; Abhayawansa & Abeysekera, 2008; McCracken et al., 2018), and the remaining stakeholders with legitimate interest in the company (Moneva et al., 2006; Branco & Rodrigues, 2008). The disclosure of these intangible resources is voluntarily reflected in corporate reports, allowing for a complete reflection on the company's value. Therefore, they are considered a necessary complement to traditional financial statements (Guthrie et al., 2008; Kent & Zunker, 2013; Ramírez & Tejada, 2022; Tejedo-Romero & Araújo, 2022). Such reports are mostly known as corporate annual reports or integrated reports, and concern corporate responsibility (CR), sustainability, the environment, corporate governance (CG), and IC reports, in addition to financial statements. Some researchers have analysed voluntary information disclosure in these reports (e.g., Abeysekera, 2008; Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Tejedo-Romero, 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2017; Cea, 2019; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021). amongst the different types of corporate disclosure, social issues are prioritised (McCracken et al., 2018; Brooks & Oikonomou, 2018; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021; Tejedo-Romero & Araújo, 2022). Some types of corporate disclosure can be mandatory, such as the information that accounting standards and legislation require companies to provide (Campbell et al., 2003; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021; Aguado-Correa et al., 2023). However, others may be non-mandatory, also called voluntary disclosures (Lim et al., 2007; Rodrigues et al., 2017; Pucheta & Gallego, 2019), in which companies make disclosures beyond what is mandated (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Sierra et al., 2018; Doni et al., 2020). According to previous researchers, there are potential benefits associated with voluntary disclosure, ranging from improving transparency, enhancing reputation, brand value, motivation of employees, to supporting the internal control processes of the company. In this context, companies provide HC information as part of their voluntary disclosure of corporate reports (Álvarez-Domínguez, 2012; Gamerschlag, 2013; Tejedo-Romero, 2016; Parsa et al., 2018).

Accounting systems have been the main sources of information for assessing business risks. However, the information provided by these systems, typically of an economic-financial nature, is complemented by other types of financial and non-financial information. In many cases, this information is provided on a voluntary basis to promote transparency, sustainability, and the long-term development of companies. This complementarity between mandatory and voluntary disclosures, both financial and non-financial, provides a comprehensive understanding of a company's risks. This increases the confidence of investors’, consumers’, and society’ confidence in a company. Thus, the evolution of reporting systems that incorporate other types of information, such as social and environmental information, allows companies to gain, maintain, or restore their legitimacy (Campbell et al., 2003; Kilian & Hennigs, 2014; Nègre et al., 2017; Parsa et al., 2018; Aguado-Correa et al., 2023).

Research on HCD has focused on either SR or IC in isolation (Abeysekera, 2008; Gamerschlag, 2013; Kent & Zunker, 2013; Parsa et al., 2018). However, these studies have provided inconclusive and heterogeneous results with respect to the themes or areas revealed (training and development, entrepreneurial skills, equity issues, employee safety, employee relations, employee welfare, employee-related measurements, injury rates, and absenteeism). To improve the understanding of disclosure practices, there have been calls for further research on HCD (e.g.: Abhayawansa & Abeysekera, 2008; McCracken et al., 2018). For instance, McCracken et al. (2018) report pressure from regulators, communities, and other stakeholders to enhance HC information disclosure. The European Commission (2014) announced the adoption of Directive 2014/95/EU for the disclosure of diverse non-financial information by large companies, highlighting the revelation of social and employee-related aspects. In this study, HCD is defined as any type of information related to the characteristics of workers that contribute to the generation of wealth in companies (knowledge, experience, values, competences, abilities, attitude, and commitment) and is relative to employers’ policies (equal opportunities and diversity, health and workplace safety, training and education, labour relations, and trade union activity). As CR reports enable companies to voluntarily meet the demands of their stakeholders (Gray et al., 2014; Tejedo-Romero, 2016), the objective of this study is to determine the level of HCD in such reports (i.e. the amount of HC information disclosed).

Hence, following Aguilera (2005), Michelon and Parbonetti (2012), and Rao and Tilt (2016), the role of boards of directors (BDs), their composition, leadership, and structure, as well as independent directors, can be examined in terms of best practices in CG, sustainability, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure. The composition and quality of BDs influence the extent to which managers disclose corporate information (Gul & Leung, 2004). Thus, it is important to identify the factors that prevent or lead companies from becoming involved in HCD, particularly if these practices are influenced by the way companies are governed. There is reasonable consensus in the literature that CG, particularly BDs, plays an important role in disclosure and transparency (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Li et al., 2008; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017a). The BD is involved in addressing company disclosures and related practices because its effectiveness depends on its ability to manage the demands of key stakeholders who provide the support and resources the company needs. As important control mechanisms in a company, they are accountable to a wide group of stakeholders. The board is seen as a monitoring and controlling device whose job is to review and evaluate the performance of management in running the firm and is ultimately responsible for ensuring that shareholder wealth is maximised (Donnelly & Mulcahy, 2008). This makes them play an important role in ensuring a company's legitimacy and reputation, thereby significantly influencing the improvement of information disclosure to stakeholders.

However, little attention has been paid to how specific board attributes—mainly the role of independent directors—influence HCD. Michelon and Parbonetti (2012), p. 400 argue that disclosure policies emanate from the BD, which is the ‘apex of the decision-making process’ and ultimately responsible for social strategy. Based on this background and the postulates of legitimacy, stakeholder, and resource dependence theories, this study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by investigating the influence of BD on HCD in corporate reports over a ten-year period in Spanish companies, while controlling for other company characteristics.

This study has two closely related aims. First, we explore whether HC-related information changed over time in response to the call of Jindal and Kumar (2012) regarding the need for longitudinal studies for determining the pattern of changes in HCD over time. Second, we aim to determine the effects of BD characteristics on HCD as few studies have examined this. Abeysekera (2010), who studied the influence of board size on the disclosure of IC by listed companies in Kenya, suggests that future research should focus on other board attributes. Hence, this study attempts to fill this gap by examining the impact of board leadership structure (wherein the chief executive officer (CEO) also holds the position of the chairman of the BD, such that CEO duality results in an intensification of managerial power) on HCD. To extend this analysis, we examine whether the effect of CEO duality on HCD is moderated by independent directors (a relationship that previous research has not examined). To achieve these aims, we conducted a manual content analysis (using disclosure indexes) on 210 corporate reports from the Spanish stock exchange's benchmark index (Ibex35) companies for the period 2007–2016. We employed a system generalized method of moments (GMM) to estimate a dynamic model of the relationship between HCD and BD characteristics.

Spain is a relevant country for the analysis of HCD and BD characteristics for several reasons. On one hand, the country is characterised by its commitment to sustainability, promoting the preparation of CR reports (Sierra et al., 2013; KPMG, 2013; Reverte, 2015; Romero et al., 2019; Aguado-Correa et al., 2023). The recognition that Spanish society, and investors in particular, has increasingly demanded more information on CSR has led directly to the adoption of measures to expand non-financial reporting, which is aligned with what is occurring throughout the rest of Europe (Sierra-García et al., 2018; Fernandez-Feijoo, Romero, & Ruiz Blanco, 2019). The Spanish government has implemented initiatives to promote the voluntary revelation of IC and social information (ICAC, 2002; Spanish, 2011). The tendency of Spanish companies to present themselves as socially responsible, moving together towards greater transparency and the desire to improve communication with stakeholders, are key aspects that justify Spanish companies achieving high scores on various sustainability indices (García-Benau et al., 2022; Sierra-García et al., 2022). Directive 2014/95/EU has been recently adapted into Spanish legislation, effective from the end of December 2018 under Law 11/2018 on Non-financial Information and Diversity (Spanish, 2018). According to Spanish legislation, the requirements on disclosure of non-financial information are only applicable to publicly limited companies, limited liability companies, and limited partnerships by shares that simultaneously have the status of public interest entities whose average number of employees during the financial year exceeds 500. These companies are considered large companies, as defined by Directive 2013/34/EU, whose net turnover, total assets, and average number of employees determine their qualifications. On the other hand, empirical studies on CG and the disclosure of listed companies have generally been conducted in Anglo-Saxon settings, with a prevalence of shareholders’ rights over the rights of other stakeholders (Garcia et al., 2011; Fuente et al., 2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017a). In this sense, Prado-Lorenzo and Garcia-Sanchez (2010) highlight the need for further studies to analyse the role of BD in countries that are more orientated towards stakeholders. This requires extending previous empirical evidence by analysing Spanish companies, in which the legal protection of shareholders is not as extensive as that of Anglo-Saxon markets. According to Fuente et al. (2017), Spain has low market activity in terms of corporate control as compared to the Anglo-Saxon context and follows a stakeholder-centred government model (Aguilera, 2005; Garcia et al., 2011). Therefore, it is necessary to disclose more information to improve stakeholders’ knowledge and trust in companies. Moreover, Spanish companies do not have an organisational separation between management and supervision, and their powers are attributed to BDs. Therefore, BD members manage the company and supervise its activities, which provides additional motivation for analysing the role of CG in companies’ disclosure practices (Garcia et al., 2011). Under this premise, BD in Spanish companies can be understood as guaranteeing information and protecting stakeholder interests by increasing transparency through HCD information.

This study provides new insights into how certain characteristics associated with BD affect HC-related communication performance. Additionally, it sheds light on the relationship between HCD and board leadership structures. This finding highlights the moderating effect of independent directors on the CEO duality–HCD relationship.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews existing literature and addresses hypothesis development. Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 presents the most relevant results and discussion of the same. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper.

2Literature review and hypotheses developmentHC is defined as a critical intangible resource for companies; it is a knowledge resource that, because of employees’ knowledge, experience, values, skills, abilities, attitude, commitment, satisfaction, and creativity, contributes to generating wealth in companies (Ramírez & Tejada, 2022; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2022). Thus, companies must behave ethically and responsibly towards their employees, implementing SR policies such as equal opportunities and diversity, health and work safety, training and education, labour relations, and union activities. This contributes to the creation of sustainable competitive advantage.

According to Branco and Rodrigues (2008), socially responsible human resource management practices, such as fair wages, a clean and safe working environment, training opportunities, health and educational benefits for workers and their families, provision of childcare facilities, flexible working hours, and work sharing, can direct companies by increasing morale and productivity, while reducing absenteeism and staff turnover. Generally, companies with a strong commitment to CSR have a greater capacity to attract better candidates, retain them after hiring, and maintain high employee morale (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Tejedo-Romero & Araújo, 2022).

However, these resources are not adequately reflected in traditional accounting systems because of the existence of strict accounting criteria for the recognition of intangible assets, which do not allow HC to be shown as assets on the balance sheet (Abhayawansa & Abeysekera, 2008; Khan & Khan, 2010; McCracken et al., 2018; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2018). Therefore, a company's true value is not reflected, decreasing the usefulness of accounting-based information (Bozzolan et al., 2003). To reflect their true value, companies resort to the voluntary use of HCD in their corporate reports.

Companies voluntarily disclose information in their corporate reports for several reasons, such as to reduce conflicts of interest, mitigate information asymmetry problems, meet community expectations in response to certain threats to the company's legitimacy, control specific groups of stakeholders, or improve access to critical resources, such as finance. According to An et al. (2011), HCD can be expected to reduce information asymmetry between companies and their stakeholders (e.g. employees, customers, supplier loyalty, and labour unions), consequently improving the relationship between them. Many firms (particularly large quoted companies) use CSR information and communication tools to foster their reputation, image, consumer loyalty, and social recognition (Cea, 2019).

2.1Board leadership structure and human capital disclosureCompanies may use information disclosure to gain or maintain the support of powerful stakeholders. Li et al. (2008) indicate that because BD manages information disclosure in corporate reports, board composition may be an important factor in deciding the type of information revealed. In this context, the present study considers BD an essential element for promoting HCD. No single theory explains the general pattern of the links between BD and disclosure. Therefore, this study uses three theories—resource dependence, stakeholder, and legitimacy—to determine how board leadership structure (CEO duality) affects HCD.

Resource dependence theory highlights the role of BD in ensuring the flow of critical resources (knowledge, personal ties, or legitimacy) into a company (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). BD provides the following four types of benefits: advice and counsel; legitimacy; channels for communicating information between external organisations and the company; and preferential access to resources (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005). Linking this theory with the stakeholder theory, a board's effectiveness depends on its ability to manage the demands of the main stakeholders who provide the support and resources required by the company (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Garcia et al., 2011; Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). Rao and Tilt (2016) suggest that BDs, being major control mechanisms in the company, are responsible for and accountable to a wider group of stakeholders. Similarly, from the legitimacy theory perspective, it is also a way of ensuring that decisions are made in the best interests of the society that provides resources. Michelon and Parbonetti (2012) and Mallin et al. (2013) consider BD a mechanism of legitimacy and reputation to enhance corporate disclosure to stakeholders.

CEO Duality. Duality occurs when the CEO holds the chair position as well (Appuhami & Bhuyan, 2015). CEO duality contributes to a concentration of power in decision-making that may harm the board's governance role regarding disclosure policies (Gul & Leung, 2004; Li et al., 2008; Rashid et al., 2020; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017a), and can negatively affect the information available to stakeholders. Powerful CEOs may be reluctant to disclose HC-related information because they fear improving the effectiveness of external controls through informed shareholders, financial analysts, key stakeholders, or society (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). This behaviour may negatively impact the legitimacy of management decisions (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005) and damage the company's relationship with the broader group of stakeholders. The CEO has access to privileged information that addresses the company's competitive advantages and internal conditions. This superior knowledge makes CEOs less motivated to share information with various stakeholders or board members. Therefore, CEOs tend to restrict voluntary corporate disclosure. Empirical studies have found varying results regarding the influence of duality on voluntary disclosure. Cerbioni and Parbonetti (2007) find that CEO duality is negatively associated with IC disclosure, while Allegrinig and Greco (2013) and Rashid (2020) report similar results for voluntary disclosure and CSR, respectively. However, Li et al. (2008) report no evidence of a significant relationship between IC disclosure and CEO duality, while Michelon and Parbonetti (2012) find no relationship between CEO duality and sustainability disclosure. Finally, Tejedo-Romero and Araujo (2022) indicate that CEO duality is negatively correlated with HCD. This is because CEO duality may lead to inefficient board functioning and reduce the motivation to improve transparency. This supports the premises based on resource dependence, legitimacy, and the stakeholder theory. Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: There is a negative relationship between CEO duality and HCD level.

Board Independence. It is often associated with a high presence of non-executive or independent directors (Prado-Lorenzo & García-Sánchez, 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Hidalgo et al., 2011) and is a tool that links a company with its stakeholders and the society (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). According to García‐Sánchez and Martínez‐Ferrero (2018), independent directors are external professionals with no other relationships with the company. They represent the interests of the shareholders and other stakeholders. CG reformers are increasingly focusing on independent directors (non-executive directors) in the hope that they will increase transparency and accountability (Aguilera, 2005; Amran et al., 2014). BDs are often argued to benefit from non-executive members possessing diverse views, skills, and professional experience (Rodrigues et al., 2017). Board independence is considered a key feature of good governance in companies (Khan et al., 2013; Khaireddine et al., 2020), in which decisions are made without bias or personal interests (Jizi, 2017; Romano et al., 2020). Theoretically, independent directors have closer relationships with various groups of stakeholders, know their expectations better, and are more likely to satisfy their interests (Ibrahim & Angelidis, 1995). According to the resource dependence theory and stakeholder legitimacy perspective, independent directors can provide knowledge, prestige, and broader contacts (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005; Appuhami & Bhuyan, 2015; Rao & Tilt, 2016). The stakeholder theory emphasises the importance of having independent directors on the board to protect investors’ interests (Arayssi et al., 2016). Thus, independent outside directors can enhance legitimacy by acting as representatives of different stakeholder groups (Ntim & Soobaroyen, 2013). Independent directors can also attract valuable resources to companies through external dialogues with stakeholders and other organisations and enhance companies’ reputation (Mallin et al., 2013). In this context, independent directors could play a key role in corporate information disclosure (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Li et al., 2008), showing responsible behaviour that protects the interests of all stakeholders (García et al., 2011), encouraging companies to react positively to social pressure, and consequently increasing the level of HCD.

Empirical research has produced mixed results regarding the influence of board independence on information disclosure. Most studies have found a positive relationship between board independence and voluntary disclosure (Aguilera, 2005; Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2015; Ortas et al., 2017; Wang, 2017; Khaireddine et al., 2020; Amosh & Khatib, 2022), supporting one of the major roles of the board- its control functions (Fama, 1980). Others (Eng & Mak, 2003; Gul & Leung, 2004; Haniffa & Cooke, 2005; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2017) have found a negative relationship, showing that an increase in the number of independent directors reduces the need to disclose more information. Finally, some studies (Hidalgo et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2013; Allergrini & Greco, 2013; Rao & Tilt, 2016; Bueno et al., 2018; Miras-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Pucheta & Gallego, 2019) have argued that the independence of the board of directors does not motivate companies to disclose, and no such relationship can be found. The mixed results for independent boards and online disclosures show that independent directors’ individual preferences and interests may also influence the decision-making process (Bansal et al., 2018). Furthermore, Li et al. (2008), p. 139 note that independent directors do not influence information disclosure because they are not necessarily independent.

Based on the arguments of the resource dependence theory and legitimacy perspective, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: There is a positive relationship between board independence and HCD level.

The moderating role of board independence. The CG literature suggests that a variety of control mechanisms can weaken the negative association between CEO duality and corporate disclosure (Zaid et al., 2020). These include a higher proportion of non-executive directors (Gul & Leung, 2004). Independent directors are typically individuals with relevant expertise and professional reputation to be protected, with no management functions or ties to the company. It is likely that when CEO duality exists, independent directors play a moderating role in corporate information disclosure (Gul & Leung, 2004; Aguilera, 2005). Moreover, independent directors do not have any relationship with the firm and tend to engage in more CSR-related activities (Pucheta et al., 2019) to avoid negative media exposure (Johnson & Greening, 1999). Consequently, independent directors devote special attention to disclosure issues. Thus, independent boards limit the negative impact of ownership on disclosure practices (Chau & Gray, 2010). This enhances transparency and trust and ensures that stakeholders’ demands are considered. A higher proportion of independent directors results in more effective board-monitoring and limits opportunistic behaviour by top management or dominant shareholders (Fama, 1980; Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). According to the legitimacy perspective, the independence of the BD stimulates social disclosure. Accordingly, a more independent BD is expected to meet the aspirations of various stakeholders and consider means to guarantee the company's legitimacy in the environment in which it operates. Li et al. (2008) argue that independent directors encourage management to assume a proactive position of disclosure, in addition to ritualistic, uncritical adherence to prescribed standards, that reflects the relevance of the HC value to stakeholders. However, few empirical studies have examined the relationship between CEO duality and independent boards in terms of information disclosure. For example, Gul and Leung (2004) find that the negative association between CEO duality and voluntary disclosure is weaker for firms with more expert outside directors on the BD, suggesting that the expertise of non-executive directors moderates this relationship. Additionally, Amosh and Khatib (2022) suggest that an independent board limits the negative role of ownership structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Finally, Zaid et al. (2020) indicate that the effect of ownership structure on CSR disclosure is more positive under conditions of high board independence.

Therefore, we expect the negative association between CEO duality and HCD to be weaker for firms with non-executive directors. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The effect of CEO duality on the HCD level is moderated by independent board members.

Sample covers the most representative Spanish companies listed on the Ibex35 index (Sierra et al., 2013). Ibex35 is an index comprising 35 large companies that represent 90% of all shares (by value) listed on the Spanish stock market; accordingly, the results of this research are expected to be robust. Non-probabilistic sampling was performed to select the companies included in Ibex35 from 31 December 2007 to 31 December 2016. Over the years, 26 companies have been listed on the Ibex35. It was possible to obtain CSR or integrated annual reports for the 10 years for 21 companies from 2007 to 2016. A total of 210 observations (21 companies over 10 years old) were used for the balanced panel data.

3.2Spanish regulatory contextThe reporting of CG and non-financial information in Spain followed international trends and the recommendations and requirements of international and EU organisations. In the mid-1990s, there was a consensus on the need to rethink the role and nature of the BD structure in accordance to CG codes. Subsequently, the Unified Code of Corporate Governance (CNMV, 2006) distinguished the following types of directors: internal, executive, and external. These codes were updated in 2015 and characterised by the adoption of the comply or explain principles (CNMV, 2015).

Regarding non-financial information reports, the first Spanish document to refer to the importance of social information and IC disclosure was the White Paper for the Reform of Accounting in Spain ICAC (2002). This document recommends that memory contains information from both social and intangible resources. In Spain, the annual financial statements include the balance sheet, profit and loss account, statement of changes in net patrimony, current flow statement, and explanatory notes called ‘memory’. Annual financial statements and management comments are mandatory while all other reports are voluntary, such as the CR and IC Reports (Tejedo-Romero, 2016; Castilla-Polo & Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2021). Management comments should contain, amongst other items, information about the company's human resources, provided it is relevant to evolution of the business. The Spanish Government and Parliament pledged to promote the development of socially responsible practices, supporting a major debate in 2007 at a national forum of experts from the public sector and business world. In the Parliament, a SR Sub-Commission was created to discuss SR trends in companies and develop appropriate legislative measures. Recently, the European Commission introduced new requirements for non-financial information and reporting on social and employee issues through European Directive 2014/95/UE. The directive was aimed at public-interest entities with more than 500 employees, requiring them to publish information on environmental, social, and employee-related issues (García-Benau et al., 2022; Aguado-Correa et al., 2023). In this context, the Spanish Government anticipated the possible outcomes of Directive 2014/95/EU, approving Law 2/2011, the Sustainable Economy Law (Spanish, 2011). Accordingly, it aimed to promote responsible practices that could become significant drivers of Spain's competitiveness and transformation into a more sustainable society (Reverte, 2015; Luque-Vílchez & Larrinaga, 2016). Although the Spanish Government plays a pivotal role in the development of socially responsible practices, the disclosure of social information is not mandatory for Spanish companies. The transposition of Directive 2014/95/EU by Royal Decree-Law 18/2017 established new mandatory requirements for non-financial reporting, which were enforced on 1 January 2017. The new law obliges public limited, private limited, and public-interest entities (defined as large companies employing at least 500 workers) to disclose non-financial information on environmental, social, and employee-related issues related to human rights, anti-corruption, and bribery matters (Sierra-Garcia et al., 2018).

3.3Variables and data collection3.3.1Dependent variableThe dependant variable was the HCD index. It was constructed using the content analysis methodology (Krippendorff, 2004). This methodology involved gathering data in which qualitative and quantitative information was codified into 24 items within five predefined categories based on the selected framework (see Appendix 1). This framework included elements and categories used in previous studies (Sveiby, 1997; Guthrie & Petty, 2000; Abeysekera & Guthrie, 2004; Abeysekera, 2008; Abhayawansa & Abeysekera, 2008; Jindal & Kumar, 2012; GRI, 2013; Cui et al., 2018; McCracken et al., 2018; Rashid et al., 2020; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2022).

The sampling units followed the terminology described by Krippendorff (2004), that is, CR or integrated reports. As CR reports1 are a way for companies to voluntarily meet the demands of their stakeholders (Gray et al., 2014), our objective was to study these reports. They are important for companies to communicate with different stakeholders because they provide a complete analysis of voluntary disclosure and are similar to IC reports. The companies in the sample opted for alternative reports, such as the stand-alone CR report, which was included within the annual report, and IR. For this study, the stand-alone CR report prevailed in the research analysis whenever companies jointly elaborated on the stand-alone CR report and IR or the annual report with the CR report section. On one hand, standalone CR reports provide more extensive and detailed information. On the other hand, the information disclosed in annual reports and IRs overlaps with stand-alone CR reports. The context units were sentences and the registration units included the presence or absence of information in the sentences. Therefore, if the same information was repeated in the report, it was considered only once (Bozzolan et al., 2003); if information about different elements of the HC was disclosed in the same sentence, the different elements disclosed were considered and codified (Rodrigues et al., 2017).

The HCD index was used to quantify the presence or absence of information regarding an item or element. Each sentence was coded using the following score: 1 if the report disclosed information on the item, and 0 otherwise. An unweighted index was developed by assigning a score to each item (Rodrigues et al., 2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017b). Considering that there is no universally accepted table of weights and because of the degree of subjectivity attached to them, weighted indexes were not used. For each company, the total disclosure index score was calculated as the ratio between the total disclosure score and maximum disclosure possible. Considering that all items were equally weighted, the adjustment did not penalise companies that, for some reason, did not disclose any of the items considered. The HC index took values between 0 and 1.

A concern with the content analysis method is its reliability (Krippendorff, 2004). Three types of reliability, accuracy, reproducibility, and stability were examined in this study (Bozzolan et al., 2003; Beattie & Thomson, 2007).

First, accuracy was guaranteed during the coding process conducted by the authors (all with graduate degrees and previous experience with content analysis), who followed the following coding procedure: a) in the initial coordination phase, a set of coding rules was discussed and established; b) subsequently, the authors carried out an in-depth analysis of five reports issued by two pilot companies. It was found that there were less than 5% discrepancies in the coding process; c) controversial points were discussed and new coding rules were introduced. Second, the reproducibility of content analysis was assessed using Krippendorff's alpha. After the second round, the authors independently completed the coding and obtained a value of 0.80 which is an acceptable level of agreement (Milne & Adler, 1999). Third, to examine the stability, a sample of four corporate reports issued by two pilot companies was reanalysed after one month. The results for the two coding round were relatively similar, with no major differences. Therefore, stability can be guaranteed, because the coding process was invariable over time (Abeysekera, 2008).

3.3.2Independent, moderating and control variablesCEO Duality is an independent variable. It is a dummy variable that takes the value of one when both functions are carried out by the same person, and zero when the functions are separated (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Li et al., 2008).

Board Independence is a moderating variable. It is the ratio of the number of independent directors to the total number of directors (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Li et al., 2008).

Independence*Duality is an interaction term. It is used to assess the moderating influence of board independence on duality.

Consistent with previous literature, several control variables were considered to avoid bias in the results.

Gender Diversity. This is the ratio of the number of female board members to the total number of board members (Prado-Lorenzo & Garcia-Sanchez, 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2017). Gender diversity is a valuable resource that provides a competitive advantage to a company (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2017). According to Tejedo-Romero et al. (2017b), it enhances the collective intelligence of a board and contributes to increasing the pool of talent available for the company's highest management and oversight functions. According to the resource dependence theory, the skills, personal attributes, and gender-related values of female directors improve disclosure and transparency of companies. Therefore, gender diversity amongst directors influences HCD decisions (Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017b; Pucheta et al., 2019).

Board Size. This was measured as the number of members on the board (Rodrigues et al., 2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017b). Board size significantly influences management efficiency, effectiveness, and supervision (Hidalgo et al., 2011). Therefore, a large board may lead to a) an increase in diversity, experience, and knowledge (Hidalgo et al., 2011; Fuentes et al., 2017) and b) an improvement in the decision-making process given the level of provided information (Pucheta & Gallego, 2019; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2022).

Board Activity. This is measured as the number of board meetings held during the financial year (Prado-Lorenzo & Garcia-Sanchez, 2010). The resource-based theory suggests that the frequency of board meetings is important for improving board effectiveness (Tejedo-Romero, 2022). Prior empirical research has found that more meetings make boards more diligent and encourage them to satisfy stakeholder needs (Allegrini & Greco, 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2017; Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017b). Thus, a company with an active board is likely to increase its disclosure level to publicise the work undertaken (Rodrigues et al., 2017). However, according to Tejedo-Romero et al. (2017b), an inverted U relationship exists, with optimal board activity identified in terms of the mid-point number of meetings. To control for the potential diminishing marginal effects on IC disclosure after the optimal level of board activity is passed, the square of the board activity variable is also considered.

Sector. Previous studies have argued that industrial sectors, such as financial services and real estate, oil and energy, and technology and telecommunications, exhibit high environmental and social sensitivity (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Sierra et al., 2013; Tejedo et al., 2017). Based on the six sectors established by the National Stock Market Commission, this variable is represented by a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a company belongs to a sensitive sector (financial services and real estate, oil and energy, and technology and telecommunication), and 0 otherwise (basic materials, industry and construction, and consumer goods).

Company Size. Company size can be a determining factor in providing voluntary information (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Hidalgo et al., 2011). Larger companies are subjected to greater pressure from stakeholders and subsequently expected to disclose more HC issues to address stakeholders’ needs (Tejedo-Romero et al., 2017b; Sierra-Garcia et al., 2018; Pucheta & Gallego, 2019; García-Benau et al., 2022). Therefore, the logarithm of the number of employees is used as a proxy for size (Rodrigues et al., 2017).

Age. Several studies have found that a company's age can be a determining factor in its provision of voluntary information (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). A mature company is concerned about its reputation and voluntarily discloses more information (Cui et al., 2018). This variable represents the seniority of the company in the market and is measured as the number of years since its establishment.

Profitability. According to Haniffa and Cooke (2005) and Li et al. (2008), profitability is a determining factor in the provision of voluntary information. Several previous studies have analysed how profitability affects information disclosure (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005; Pucheta & Gallego, 2019; Tejedo-Romero & Araujo, 2022). In this sense, profitability can be the result of continuous investment in HC; therefore, companies can participate in greater disclosure to indicate their importance in creating long-term value. We use return on assets (ROA) to measure company profitability (Li et al., 2008; Pucheta & Gallego, 2019; García-Benau et al., 2022).

Directive. This is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for 2015 and 2016, and 0 for other years. This variable controls for the influence of Directive 2014/95/UE, approved in 2014, on HCD before it became compulsory for Spanish companies (from 2017). It aims to determine whether companies, following the approval of the Directive, have generated a greater amount of HCD as a prelude to the mandatory disclosure, which took place in 2017.

Data were collected from CG reports, annual reports, and the SABI database (Bureau Van Dijk).

3.4Research modelThe following dynamic specification was considered to examine the relationship between HCD and the structure, composition, and function of the BD:

Some of the limitations of previous research include the problem of endogeneity in the relationship between voluntary disclosure and CG (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012; Rashid et al., 2020). To solve the endogeneity issue, the model was estimated using the system GMM, which combines the equations in the first differences and levels of the system of equations. It employs both lagged levels and differences as its own internal instruments and assumes that the error terms are independently and identically distributed across the dataset. The efficiency of the system GMM depends on the assumption that the dependant and other explanatory variables are valid instruments, and that the error terms do not exhibit serial correlation (Roodman, 2009). To limit small-sample problems, the number of lags was limited to one or two periods for the equations in difference. A collapsed instrument matrix was used to avoid problems arising from the presence of excessive instruments. Robust standard errors were estimated using a two-step approach from Windmeijer's (2005) small-sample correction to avoid biased results. As an additional instrumental variable, ownership concentration, which is not in the model, is included to complement the instruments generated using the GMM procedure.

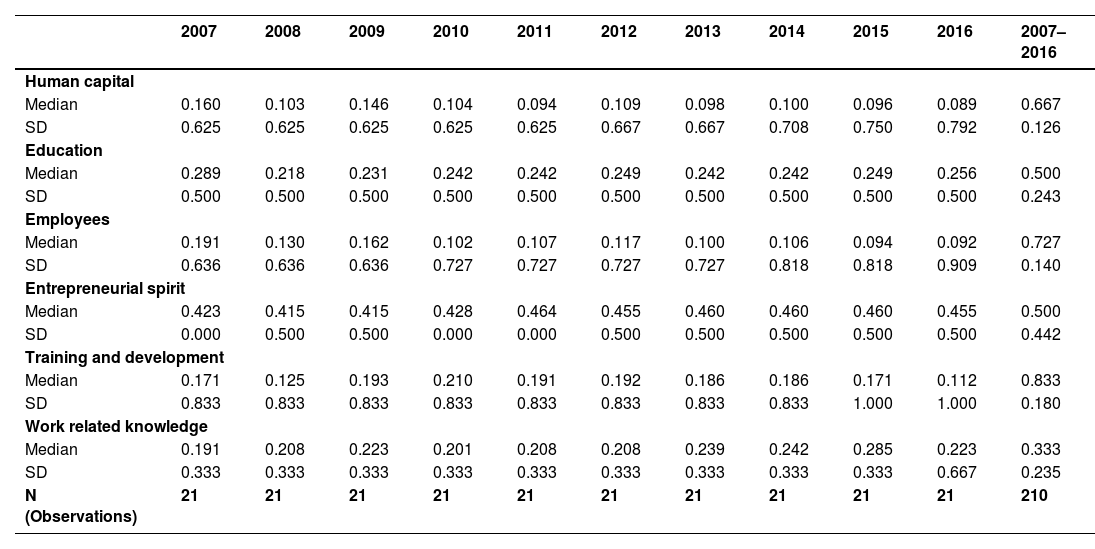

4Results and discussion4.1Descriptive analysis and correlationsTable 1 shows that the extension of the HCD for the 10-year period examined ranges from 0.160 to 0.089 (median), with a mean score of 0.667, suggesting a high HC score. The increase in HCD scores slightly changed from 2007 to 2014. According to the legitimacy and stakeholder theories, the pressure exerted by Spanish Government initiatives to promote social reporting had a slightly positive influence on HCD practices. In 2014, there was an encouraging increase in HCD. This finding is similar to that obtained by McCracken et al. (2018) for the UK's FTSE 100 companies. This suggests that, following the approval of Directive 2014/95/EU, companies began to increase their HCD levels. By voluntarily adding new information to corporate reports, they anticipated the new requirements of Directive 2014/95/EU, which became mandatory in 2017. This behaviour of companies, that is, anticipating future mandatory regulation for non-financial reporting, can be considered as a mechanism of external legitimation that can help align the interests of stakeholders, meet certain expectations of society, and improve access to critical resources. This increase in HCD confirms the growing awareness and understanding of companies to value their employees through explicit disclosure.

Descriptive statistics for the human capital and sub-indexes.

Overall, Table 1 indicates that the most frequently reported dimension was training and development, with a median of 0.833 during the study period. Previous studies, such as Jindal and Kumar (2012) and McCracken et al. (2018), have considered this dimension to be the most revealing. However, this result differs from that reported by Kent and Zunker (2013), who indicate that employee-related dimensions are most frequently disclosed. The employee-related dimension was the second most revealed by Spanish companies, with a median value of 0.727. This type of information can be considered strategic by companies to attract the best potential employees and motivate and retain existing employees. According to the legitimacy, stakeholder, and resource dependence theories, companies try to legitimise their actions toward employees and the society because the success and survival of companies are subject to approval by stakeholders. Additionally, companies are interested in having stakeholders realise the true value of their employees to gain access to external resources. Parsa et al. (2018) suggest that companies are increasingly under pressure to provide an account of how fairly and ethically they treat their workforce. In summary, the disclosure of these dimensions aims to legitimise companies’ behaviour, providing information intended to influence stakeholders, and eventually, society's perceptions of the company.

Other dimensions, such as education, entrepreneurial spirit, and work-related knowledge, were least disclosed by Spanish companies, with median scores of 0.5, 0.5, and 0.33, respectively. It is possible that aspects related to employees’ knowledge and skills are the main sources of competitive advantage, and companies are not interested in revealing them. Khan and Khan (2010) and McCracken et al. (2018) report similar results for Bangladeshi and UK companies. According to Álvarez-Domínguez (2012), companies consider HC the most valuable resource amongst all value drivers. Retaining information about HC could protect against competitors and ‘headhunters’, who could use this information to acquire more skilful employees. In this sense, the dimension of the entrepreneurial spirit reflects the HC's capacity for innovation. Typically, companies report little on this topic to protect the confidentiality of their businesses because they can be quickly imitated by competitors (Abeysekera, 2008). However, Guthrie and Petty (2000) demonstrate that the entrepreneurial spirit dimension is the most frequently reported attribute of HC in Australia.

The descriptive statistics of the independent, moderating, and control variables are shown in Table 2. The continuous variables of age, company size, and profitability were winsorised at the top and bottom 5% of the distribution to eliminate the influence of outliers. The relationships between the variables are consistent with the results presented in previous studies (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Allegrini & Greco, 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2017; Rashid et al., 2020). These values did not indicate collinearity. A collinearity problem is considered severe if the pairwise correlation coefficient is greater than 0.80 (Rodrigues et al., 2017; Rashid et al., 2020).

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Note: Superscript asterisks are as follows: **significance at the 1% level; *significance at the 5% level.

Table 3 show the results of the system GMM estimation. The F-test showed that the overall regression was significant (F(14, 21)=196.23, p = 0.000). The Arellano-Bond AR(1) test identified a high first-order autocorrelation (AR(1)=−2.38; p-value=0.017), and the Arellano-Bond AR(2) test accepted the hypothesis of no second-order autocorrelation (AR(2)=−0.73; p-value=0.468). The Hansen tests, conducted to test over-identifying restrictions, indicated that the instrument set could be considered valid (Hansen test=2.95; p-value=0.708). These tests confirmed the correct specifications of the research model.

Results of dynamic panel-data estimation, two-step system GMM.

Note: Robust standard errors with Windemeijer's finite sample correction are in parentheses. *p<0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Data show that the lagged value of HCD was significant at the 1% level. In other words, the amount of HC disclosed depended on the level of HC revealed in previous years. Additionally, CEO duality was negatively related to HCD (at the 1% level). This is consistent with results from previous studies (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Allegrini & Greco, 2013; Rashid et al., 2020). According to Li et al. (2008), this concentration of power results in board inefficiency, which affects companies’ disclosure policies and reduces the information available to stakeholders. This may negatively affect the legitimacy of management decisions and damage a company's relationships with stakeholders. Moreover, according to the resource dependence theory, reducing information disclosure could worsen access to external resources. Thus, H1 is confirmed.

Furthermore, there is a negative relationship, significant at the 5% level, between board independence and HCD. These results indicate that an increase in the number of independent directors reduces the need to disclose more information. This is contrary to some studies (Cerbioni & Parbonetti, 2007; Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2015; Wang, 2017; Khaireddine et al., 2020; Amosh & Khatib, 2022), confirming that an increase in board independence increases the level of disclosure. Hence, H2 is rejected. Nevertheless, this finding is similar to those of Eng and Mak (2003), Gul and Leung (2004), Haniffa and Cooke (2005), Rodrigues et al. (2017), and Bansal et al. (2018). This is explicable because independent directors offer their services to companies that are at the centre of media attention (García‐Sánchez & Martínez‐Ferrero, 2018); therefore, they can resist HCD because they are not specialists on the issue and may also fear that their professional reputation will be affected by HCD. According to Frias-Aceituno et al. (2013), independent directors do not encourage information disclosure because of the fear of damaging their image and reputation. This affects future job prospects (Zaman et al., 2018). Moreover, they lack sufficient information on how a company manages its human resources. This lack of information is particularly relevant in the case of HCD, which deals with useful topics for a wide range of stakeholders, such as social contributions, human rights, and health at work. This suggests that independent directors may not be able to exert sufficient influence on HCD, probably because they lack the privileged information possessed by executive directors (Li et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2011).

In companies with a strong leadership structure, more independent members are expected to compensate for the CEO's concentration of power and positively influence disclosure (Haniffa & Cooke, 2005). To verify this argument, the interaction between independent directors is constructed using the CEO duality variable. The interaction variable indicates that independent directors play a moderating role in the relationship between CEO duality and HCD. Therefore, CEO duality negatively impacts HCD when board independence is equal to zero; that is, when there are no independent directors on the board. However, this effect is moderated by an increase in the proportion of independent directors. This is consistent with the resource dependence, legitimacy, and stakeholder theories, and the literature, which has argued that the advising role of independent boards acts as a moderating mechanism in the relationship between CEO duality and HCD (Gul & Leung, 2004; Aguilera, 2005). Hence, H3 was confirmed at the significance level of 1%. We recognise the importance of independent board members in overseeing and guiding CEO actions. CEO duality, in which an individual simultaneously holds the positions of CEO and chairperson, has been associated with potential conflicts of interest and reduced accountability. However, when an independent board is in place, it acts as a safeguard, mitigating the negative effects of CEO duality on organisations’ HCD.

Regarding the control variables, gender diversity has a significantly positive relationship at the 1% level. Therefore, BDs with more women provide more information about HC. This suggests that women are more responsible than men for voluntary disclosure of information (Prado-Lorenzo & Garcia-Sanchez, 2010). Board size also has a significantly positive influence on HCD at the 10% level. These results have been confirmed by Abeysekera (2010), Hidalgo et al. (2011), and Allegrini and Greco (2013). Board activity shows that the coefficients of the activity2 variables are positive and negative, respectively, significant at the 10% level. This shows the existence of a quadratic, inverse U-shaped relationship between BD activity and HCD. The positive relationship between size and age was significant at the 10% level (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012; Sierra et al., 2013). Sensitive sectors are more exposed to stakeholders’ opinions on social issues and disclose more information about HC. Similarly, age is another key factor in the literature (Michelon & Parbonetti, 2012). The sector and profitability variables are insignificant. The approval of Directive 2014/95/EU had a significant impact (significance level of 1%). Voluntary disclosure of HC information has increased since 2014. This was an attempt to prepare for the obligation to reveal HC information in 2017 through the transposition of Directive 2014/95/EU into Spain.

5ConclusionsThis study explores the influence of the HCD policy on CR and integrated reports in Spanish companies from 2007 to 2016. The HCD depends on the BD's disclosure policies. This study analysed the effect of the BD leadership structure on HCD using a system-GMM estimator to address endogeneity concerns.

The findings suggest that Spanish companies are adapting to new EU regulations, which have been mandatory for certain companies in 2017, increasing their HCD since 2014. Information disclosure about training and development was the most relevant signal that companies had responsible attitudes towards their HC. However, less disclosed information was available on work-related knowledge. Companies seem to resist disclosing information concerning their stock of knowledge, which is a critical resource for competitive advantage because this information can be used by competitors. The results indicate a change in the topics that companies have disclosed over time.

There is also evidence that the BD structure influences HCD. The data indicate that CEO duality and independent directors negatively affect HCD. However, independent directors play a moderating role in the presence of CEO duality, positively and significantly influencing HCD. Additionally, female directors and board size have significant positive influences on HCD. Additionally, the data suggest that after reaching the optimum number of BD meetings, additional board meetings have little effect on reducing disclosure. More meetings do not necessarily imply more BD effectiveness. A significant relationships were found between HCD and size, age, and Directive 2014/95/EU, approved in 2014. There was no significant relationship between sector and profitability.

In terms of practical, social, and political implications, the results could be significant to stakeholders, shareholders, and governments because they can contribute to enhancing the decision-making processes regarding employment, investment, and regulatory issues. As more information about companies’ responsible practices concerning HC becomes available, the relationships amongst employees, unions, and the government can improve. Greater transparency of information regarding the stock of knowledge, which is a critical resource for the company's competitive advantage and the employees themselves, can also be used to attract talented employees. This is because it signals the importance of existing employees as intangible resources, which could help attract and retain them. Furthermore, the results could have social implications for managers and other stakeholders, such as labour unions. HCD can be used as a mechanism to control the management of human resources by companies, which encompasses labour practices and fulfilment of good working conditions. Trade unions are important pressure groups in the labour market and in the political field in most developed countries, such as Spain. They have significant power to influence responsible HR management practices, emphasising why the importance of HCD acquires great relevance. Finally, the findings suggest that independent members play an important role in CG, especially when CEO duality exists because they can moderate a strong leadership structure, helping to increase HCD. Therefore, the contributions and expertise of these independent members are recommended to ensure greater transparency of CG information. This research is useful for governments and decision-makers proposing changes to CG codes. This finding suggests that non-mandatory recommendations do not have the same effect as mandatory recommendations in terms of corporate disclosure.

Overall, to strengthen CG, the following recommendations can be made: a) Enhance board independence: establish a board of directors with a majority of independent members who possess knowledge about HCD issues, ideally with accounting expertise and who awareness of the relevance of disclosing these issues. b) Separate CEO and chairman roles: consider separating the roles of CEO and chairman to promote a system of checks and balances. This separation helps ensure that no single individual has unchecked power and that decision-making is subject to objective scrutiny. c) Foster a culture of transparency and accountability: promote a corporate culture that emphasises transparency, integrity, and accountability across all levels of the organisation. This can be achieved by clearly defining ethical standards, regular reporting, and mechanisms for employees to raise concerns without fear of retaliation. d) Regular evaluation and assessment: conduct periodic evaluations of the board's performance, including its independence and effectiveness in overseeing the CEO's actions. This evaluation should encompass the board's composition, diversity, expertise, and adherence to CG best practices. e) Shareholder engagement: encourage the active participation of shareholders to ensure that their interests are represented in the corporate decision-making processes. This may involve regular communication, meetings with shareholders, and including shareholder perspectives in strategic discussions. From a stakeholder theory perspective, shareholder engagement is critical for ensuring that corporate decisions consider the interests of all relevant stakeholders. By proactively engaging shareholders, a company can gain a more complete understanding of the different views and needs of its stakeholders, which can subsequently influence strategic decision-making to achieve balance and mutual benefit.

By implementing these suggestions, organisations can enhance their CG standards, reduce the risk of conflicts of interest, and establish a supportive atmosphere to foster the growth and development of their HC.

Although these studies provide important theoretical and practical contributions, the findings of this study have some limitations. First, by referring to an applied dynamic model, several control variables were considered in the analysis; however, other variables could have been included, such as those related to debt or CEO and board tenure. Second, regarding the sample selected, we are aware of the limitations of the typology of companies included in Ibex35 (large companies listed on the Spanish stock market). Additionally, we were limited by the fact that we had information on only 21 companies whose CR reports were elaborated on and disclosed over the entire study period (10 years). Third, the choice of our index, which only examined the presence or absence of information in sentences (quantity of HCD), did not allow us to study the depth of the information provided (quality of HCD). Fourth, our sample consists only of large Spanish companies included in Ibex 35 because of data constraints, which could limit the extension of our findings to smaller companies.

Considering the aforementioned limitations, future research could study other firms, preferably smaller ones, with different problems than those analysed in this study. Additionally, analyses can address whether these companies voluntarily disclose less information. Efforts can then be focused on defining which mechanisms, if any, can reduce information asymmetry in smaller companies, considering the disclosure costs that the companies may incur.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.