Legitimacy is fundamental to business internationalization and access to new markets. This variable is particularly important for emerging market multinationals (EMNEs) as they face numerous obstacles, including the information that consumers in the host country have about these companies in addition to the legitimacy of the country of origin. Therefore, this study tests whether home country information and legitimacy affect the legitimacy of EMNEs and consumer purchase intentions. Specifically, this research focuses on EMNEs of Chinese origin due to their rapid growth at the international level and in the fast fashion sector because of the change in the positioning of large brands in favor of sustainability. The model is validated through an empirical study of 261 regular Shein shoppers using PLS-SEM. The academic and managerial implications of this research clarify the antecedents and consequences of the legitimacy of EMNEs and provide recommendations for the management of EMNEs and business success.

Legitimacy plays a key role in internationalization and access to new markets (Kostova et al., 2008). Companies must legitimize themselves to survive (Blanco-González et al., 2023; Butkeviciene & Sekliuckiene, 2022) and achieve business success in international markets (Del-Castillo-Feito et al., 2021). One of the most frequently asked questions in the legitimacy literature is how do companies achieve legitimacy in foreign markets? (Jiang et al., 2022; Park, 2018; Popli et al., 2021; Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022).

Legitimacy refers to the “perceived appropriateness of an organization to a social system in terms of rules, values, norms, and definitions” (Deephouse et al., 2018), p. 9). According to Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2022), the search for legitimacy involves recognizing the importance of the social system in which companies and individual evaluators reside, which may differ from country to country. The academic literature has shown that legitimacy facilitates access to essential resources (Beddewela et al., 2017), generates social identity (Buhmann & Schoeneborn, 2021; King & Whetten, 2008), and strengthens employee engagement and performance (Chaney & Martin, 2017; Decuypere & Schaufeli, 2020; Moisander et al., 2016). Legitimacy generates a feeling of trust and security that is essential in international environments to reduce uncertainty and risk perception (Desai, 2008) as well as to establish relationships with stakeholders in host countries (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). Companies that are legitimized increase stakeholders' willingness to accept the actions taken and decisions made (Haack et al., 2021; Tyler, 2006). This makes legitimacy a sustainable competitive advantage for the organization (Miotto et al., 2020) and a dynamic capability that companies must manage to achieve success in their internationalization (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023).

Emerging multinational enterprises (EMNEs) with a permanent presence abroad and whose home country is an emerging economy face the challenge of legitimizing themselves in international markets. Previous research has highlighted that Chinese EMNEs face numerous challenges when doing business on a global scale (Peng, 2005), especially in developed economies, due to their lack of legitimacy, among other reasons (Child & Rodrigues, 2005; Park, 2018); Popli et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2012). However, the likelihood of achieving the same level of legitimacy as enterprises in highly developed host countries is low (Bangara et al., 2012; Madhok & Keyhani, 2012; Ramachandran et al., 2012). Even if EMNEs manage to adapt their actions to the host country's social system (Zabala-Aguayo, 2022), they are often challenged by their origins, that is, the information consumers have about the EMNE's country of origin. Consumers use such information to form their first impressions of legitimacy (Haack et al., 2021). A country's legitimacy is a key resource for business environments because it contributes to institutional stability, reducing the concerns and fears of companies that want to operate in the country (Díez-Martín et al., 2016). Countries encourage entrepreneurial activity through state legitimacy, thereby providing an attractive framework for companies (Díez-Martín et al., 2021b).

However, the growth of some EMNEs at the international level is unquestionable (Zabala-Aguayo, 2022). For example, the market value of Shein (a Chinese EMNE) has been growing exponentially since 2019, with a market capitalization of US$5 billion. By the end of 2022, Shein's value had increased 20-fold, reaching US$100 billion (Statista, 2023). Can this penetration success be explained by the legitimacy of this EMNE? What role does the legitimacy of the country of origin play in the EMNE's legitimacy? Some gaps in this regard remain unexplored in literature. Responding to these questions would advance our understanding of the relationship between legitimacy and internationalization, the role of country legitimacy, and the development of more effective internationalization strategies.

The objectives of this research are 1) to determine the effect of country-of-origin legitimacy on the legitimacy of EMNEs in host countries, 2) to quantify the role of consumer information on country-of-origin legitimacy and the legitimacy of EMNEs, and 3) to analyze how consumer information and the legitimacy of EMNEs impact the purchase intention of host consumers. These objectives seek to advance the antecedents and consequences of the legitimacy of EMNEs. They have also made it possible to obtain new recommendations for EMNE management. Achieving legitimacy for EMNEs in host countries is a priority objective, and counteracting the disadvantages generated by the information available to consumers in host countries (Buckley & Ghauri, 2015; Madhok & Keyhani, 2012; Zaheer, 1995), which indicates whether the activity undertaken by EMNEs is good for society, is a challenge they must face not only to survive but also to increase their sales.

The structure of this paper is as follows. First, the theoretical framework is presented, justifying five hypotheses that suggest relationships among the legitimacy of EMNEs, the legitimacy of the country of origin, consumer information, and purchase intention. Second, the sample and methodology used in this study are explained. This study was conducted in the fast fashion sector, as this sector represents a competitive and dynamic industry in which changes are being implemented in business models and value chains toward ethical behavior (Miotto & Youn, 2020) and important cultural differences are observed among consumers in different countries. PLS-SEM multivariate analysis was used to test these hypotheses. Third, the results are presented, including validation of the measurement scales and evaluation of the structural model. Finally, the implications of this research are discussed, and future research directions are formulated.

2Theoretical framework2.1Country of origin legitimacy and legitimacy of EMNEsLegitimacy is one of the variables that is receiving the most attention in academia (Díez-Martín et al., 2021b) due to the fact that organizations need social support to survive and to be successful in the long term (Deephouse et al., 2016). According to Suchman (Suchman, 1995), p. 574), legitimacy is “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.” In the field of internationalization, the academic literature on legitimacy is often based on Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), as it focuses on how legitimacy may vary from country to country and thus has an impact on the expectations of a particular country's society and the business performance achieved.

The core principle of the Institutional Theory is that companies must gain and maintain legitimacy to survive in new markets (Gölgeci et al., 2017; McKague, 2011). This lack of legitimacy makes it difficult to obtain resources or support from stakeholders in host countries (Chen et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2022). When a company is devoid of legitimacy or demonstrates insufficiency, it frequently finds itself in a situation of social eviction, generally with no solution (Bronnenberg et al., 2000).

In contrast, firms that are perceived as legitimate are in a better position to compete for resources and have unrestricted access to markets (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978; Suchman, 1995). In this regard, the importance of studying legitimacy lies in the fact that it is a key factor that can lead to the success or failure of EMNEs (Díez-Martín et al., 2021b). Companies must maintain consistency with the social systems they face. Therefore, they must be clear about the countries in which they can operate without losing legitimacy (Zimmerman & Zeitz, 2002). Adaptation without consistency generates a lack of trust in a company (Cruz-Suárez et al., 2014). For example, Del-Castillo-Feito et al. (Del-Castillo-Feito et al., 2021) demonstrated that multinational companies that act in accordance with the values of developing countries obtain better levels of legitimacy, Kostova et al. (Kostova et al., 2008) identified that legitimacy positively impacts the internationalization of companies, and Chaney et al. (2016) pointed out that legitimacy increases repurchase intention.

When a multinational company expands into a new country, it is exposed to legitimacy assessments by a new audience. When forming legitimacy judgments (Bitektine & Haack, 2015), new evaluators seek information about how companies operate in their home countries to form opinions on how they will fit into the social and ethical context of the host country. If the home country's legislation and regulations are more lenient than those of the host country or if there is corruption, country risk, or political-economic uncertainty (Paule-Vianez et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2016), the legitimacy of EMNEs from these countries will be conditional. Similarly, if the accountability or ethical standards of home countries are perceived as less legitimate (Madhok & Keyhani, 2012), they impact the legitimacy of EMNEs (Luo & Tung, 2007). Moreover, the impact of the legitimacy of the country of origin is greater in host countries with high levels of development (Jamali & Karam, 2018). Along these lines, several scientific papers have shown that the perception of corporate social responsibility (directly related to legitimacy, e.g., (Blanco-González et al., 2020) helps EMNEs enter new markets (Bhattacharyya, 2020); Yan et al., 2020, (Zhang et al., 2022). However, based on a literature review (Jiang et al., 2022; Madhok & Keyhani, 2012; Tashman et al., 2019; Popli et al., 2021) and the impact of the country of origin on the legitimacy of EMNEs, the following hypothesis is established:

- •

Hypothesis 1: Country of origin legitimacy impacts the legitimacy of EMNEs in the host country.

Legitimacy is a perception, and as such, it is determined by a number of antecedents such as reputation (Miotto et al., 2020), image (Del-Castillo-Feito et al., 2019), or perceived uncertainty (Díez-Martín et al., 2022; Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). Bitektine (Bitektine, 2011) and Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2022) analyzed the importance of active cognitive processing, knowledge, information search efforts, and social interactions as antecedents of legitimacy. Legitimacy is a perception formed based on social and individual beliefs (Haack et al., 2022) and is, therefore, based on a series of antecedents, including consumer information. Consumer information refers to a network of associations that include brand-related beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions of aspects such as quality and image (Zhang et al., 2022). Stakeholders use consumer information to make appropriate legitimacy judgments (Tost, 2011); Zelditch, 2001).

Consumer information comes from direct sources such as previous personal experiences and indirect sources such as advertising, reference groups, and media (López-Balboa et al., 2021; Erdem & Swait, 1998). Etter et al. (Etter et al., 2018) and Illia et al. (Illia et al., 2023) considered social networks to be part of consumer information and a means of legitimacy measurement. Beyond the sources that constitute consumer information, the quality of this information and regular consultation with information sources that constitute valid knowledge must be considered (Zhang et al., 2022).

Several academic studies have identified that consumer information influences the legitimacy of EMNEs (Hu et al., 2020; Marano & Kostova, 2016) because it builds perceptions of how EMNEs act before they start operating in host countries, often due to cultural (Buccieri et al., 2021) or ethnic aspects (Prashantham et al., 2019), such as gender perceptions in the host country (Javadian et al., 2021), socially accepted forms of negotiation (McDougall & Oviatt, 2000), or the host country's own institutional pressures (Aksom & Tymchenko, 2020; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2019; Popli et al., 2021).

Consumer information is relevant because it helps determine where organizations can focus their efforts to improve their legitimacy without acting on it directly (Bitektine, 2011). Therefore, it is important to identify the different sources of information that can influence the perceptions of EMNEs, as legitimacy plays a fundamental role when faced with the uncertainty generated by new companies in markets (Díez-Martín et al., 2022); Jahn et al. 2020). Focusing on Chinese EMNEs, Wang and Laufer (Wang & Laufer, 2020) pointed out that Chinese social networks are very active and constitute an important source of information. Li et al. (Li et al., 2019) confirmed that a lack of transparency is critical in many business transactions. Kim (Kim, 2022) found that Chinese companies must adapt their communication processes to generate high-quality consumer information. Bai et al. (Bai et al., 2019) examined how EMNEs accumulated legitimacy after their formation in China. However, it is unknown how consumer information impacts the legitimacy of the country of origin and, therefore, how it impacts the legitimacy of EMNEs. Thus, the following hypotheses are established:

- •

Hypothesis 2.a: Consumer information impacts the legitimacy of EMNEs’ country of origin.

- •

Hypothesis 2.b: Consumer information impacts the legitimacy of EMNEs.

Considering the sequential process of the relationships established and justifying how consumer information is an antecedent to legitimacy, this study focuses on the objective of EMNEs entering international markets to achieve profitability by selling their products. Fig. 1 illustrates the hypotheses validated in this study (Fig. 1).

Consumer information, which impacts purchase intention (Chen et al., 2020), refers to the information, knowledge, and quality of information (Zhang, 2022) and is indicative of whether the purchase is appropriate. Consumer information considers the information consumers have about an EMNE before purchasing (Wang et al., 2014). Academic literature has shown that consumer information impacts purchase intention due to informed decision-making, a reduction in perceived risk, or the trust that this information generates (Zhang et al., 2014). Likewise, research has been conducted on the impact of consumer information on sales forecasting (Morwitz, 2014) and customer experience (Kranzbühler et al., 2018). However, as indicated by Godey et al. (Godey et al., 2012), Mishra et al. (Mishra et al., 2021) and Oberecker et al. (Oberecker et al., 2008), it is necessary to delve deeper into the impact of customer information on the purchase intention of EMNE products. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

- •

Hypothesis 3: Consumer information about EMNEs impacts the purchase intention of host-country consumers.

Legitimacy influences consumer behavior and attitudes (Alexiou & Wiggins, 2019), as it generates favorable assessments of companies and products (Brown & Dacin, 1997), even generating consumer loyalty and engagement (Guo et al., 2015). When consumers perceive that a company complies with institutional norms, they are willing to grant it legitimacy and continue to support its activities within society (Valor et al., 2021). Moreover, legitimacy affects not only purchase intention but also maintenance of a long-term relationship (Miotto & Youn, 2020; Payne et al., 2021).

However, especially in the retail market, consumer decisions are based on economic, functional, and sociocultural assessments (Yang et al., 2020). Handelman and Arnold (1999) stated that companies must achieve legitimacy if they want consumers to buy their products. Kim et al. (2014) identified the effect of legitimacy, which favors consumer support over other options in a multichannel environment. Blanco-Gonzalez et al. (Blanco-González et al., 2023) validated the impact of legitimacy on consumers’ repurchase intentions. To achieve the necessary consumer attraction, EMNEs must overcome several obstacles (Pattnaik et al., 2021), for which legitimacy is a competitive advantage (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

- •

Hypothesis 4: The legitimacy of EMNEs impacts the purchase intention of host-country consumers.

The fast fashion sector was selected as the research setting. This industry operates in a competitive and dynamic market characterized by complex brand perceptions and stakeholder activism (Joyner Armstrong et al., 2018; Miotto & Youn, 2020). The fast fashion sector is considered to be one of the most polluting and socially irresponsible industries (Bly et al., 2015; Garcia-Torres et al., 2017; Karaosman et al., 2020; Pal et al., 2019). The fast fashion industry is characterized by very short product lifecycles to meet consumer needs and the need for novelty and variety, which can generate impulse purchases of new garments and the irresponsible disposal of old garments (Joyner Armstrong et al., 2018). In this sector, there is a paradox between price and sustainability that can cause ethical problems for consumers (Miotto & Youn, 2020). This paradox requires EMNEs to adapt to the host country's regulatory and ethical context, which may differ from the regulatory and ethical context of the home country, to survive (Zhang, 2022).

Chinese EMNEs in the fast fashion sector were selected for the study because their growth and penetration into international markets have increased significantly. Chinese EMNEs face numerous challenges when conducting international business (Peng, 2005) due to their lack of legitimacy, especially in developed economies (Child & Rodrigues, 2005; Sun et al., 2018). As mentioned in the introduction, the international growth of these companies is unquestionable. However, they lack legitimizing elements, such as the dissemination of sustainability reports or the communication of transparent information on ESG criteria. In addition, the choice of China as a country of origin is an interesting option from an academic and management point of view because China is currently the largest contributor of global outward foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world, making it the third largest source of FDI (UNCTAD, 2012).

From the host country's perspective, Spain is an attractive destination for multinational companies because it provides access to the European Union and has government policies that favor FDI. It is the fourth largest economy in the EU and the 14th largest in the world, with a GDP of $1.2 billion. It ranks 13th globally in foreign investment. More than 14,600 foreign companies have chosen Spain to establish themselves. Of the 100 largest companies listed in Forbes Global 2000, 70 are already present in the Spanish market (ICEX 2022). Spain is the country from which the most internationally recognized fast fashion brand, Zara, arose. The change in the position of Spanish companies in the fast fashion sector toward sustainability and an increase in their prices have left a gap for new brands that want to occupy this position in the market, such as Shein and Mulaya.

The fieldwork was conducted from April to September 2023 and targeted consumers of the main Chinese EMNE of the fast fashion industry operating in Spain, which is also experiencing the strongest growth: Shein. Moreover, Shein is the leader in online sales in Spain's fast fashion sector (Nueno & Urien, 2023). An online questionnaire was distributed to 261 regular Shein consumer. The sample consisted of 196 women, 62 men, and three of non-binary gender, aged between 18 and 34 years. The frequency of purchase for the sample was 24.1 % weekly, 31.5 % monthly, 35.5 % every two months, and 8.9 % less frequently than once every two months. The average purchase expenditure was less than 25 euros per purchase for 31.5 %, between 26 and 50 euros for 40.3 %, and more than 50 euros for 28.5 % of respondents. In none of the cases was the average expenditure higher than 100 euros. Finally, we confirmed that the sample represented Shein's target audience. Shein sells its products in more than 220 countries. Its target audience is young people between 18 and 27 years old, and its pricing policy is centered on low cost (Statista, 2023). The typical profile of the fast fashion user who considers Shein a shopping option is a woman between 25 and 34 with an average income level who buys 3.4 times a month and has an average purchase amount of 38.7 euros (Nueno & Urien, 2023).

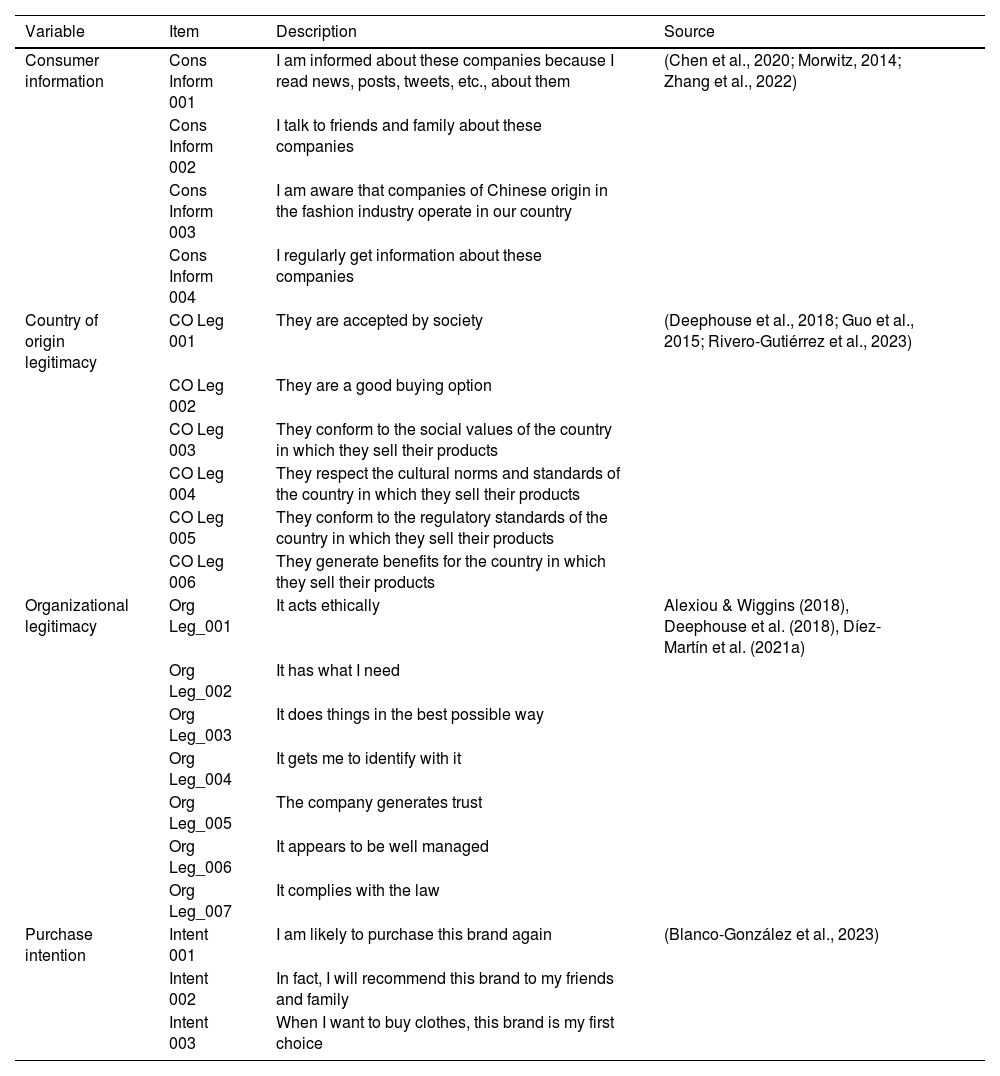

3.2Variable measurementThe questionnaire was composed of seven-point Likert scale questions, and all items were justified based on the existing literature. After testing the validity of the scales with a pre-test performed on 68 consumers in April 2023, information was collected based on the items listed in Table 1.

Items.

| Variable | Item | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer information | Cons Inform 001 | I am informed about these companies because I read news, posts, tweets, etc., about them | (Chen et al., 2020; Morwitz, 2014; Zhang et al., 2022) |

| Cons Inform 002 | I talk to friends and family about these companies | ||

| Cons Inform 003 | I am aware that companies of Chinese origin in the fashion industry operate in our country | ||

| Cons Inform 004 | I regularly get information about these companies | ||

| Country of origin legitimacy | CO Leg 001 | They are accepted by society | (Deephouse et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2015; Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023) |

| CO Leg 002 | They are a good buying option | ||

| CO Leg 003 | They conform to the social values of the country in which they sell their products | ||

| CO Leg 004 | They respect the cultural norms and standards of the country in which they sell their products | ||

| CO Leg 005 | They conform to the regulatory standards of the country in which they sell their products | ||

| CO Leg 006 | They generate benefits for the country in which they sell their products | ||

| Organizational legitimacy | Org Leg_001 | It acts ethically | Alexiou & Wiggins (2018), Deephouse et al. (2018), Díez-Martín et al. (2021a) |

| Org Leg_002 | It has what I need | ||

| Org Leg_003 | It does things in the best possible way | ||

| Org Leg_004 | It gets me to identify with it | ||

| Org Leg_005 | The company generates trust | ||

| Org Leg_006 | It appears to be well managed | ||

| Org Leg_007 | It complies with the law | ||

| Purchase intention | Intent 001 | I am likely to purchase this brand again | (Blanco-González et al., 2023) |

| Intent 002 | In fact, I will recommend this brand to my friends and family | ||

| Intent 003 | When I want to buy clothes, this brand is my first choice |

PLS-SEM was used to analyze the data described in the previous section. This analysis is based on the predictive capacity of the model for the final dependent variable according to the variance of the dependent variables (Chin, 2010). In addition, this type of analysis allows latent variables to be constructed from indicators or manifest variables so that a theoretical model can be represented and studied more easily (Hair et al., 2011).

PLS-SEM and SmartPLS4 were used for data processing. PLS-SEM is a multivariate analysis method that is comparable to other methods, such as CB-SEM or AMOS (covariance-based). The main goal is to predict dependent variables by estimating trajectory models (Hair et al., 2019; Henseler, 2017). PLS-SEM focuses on causal-predictive analysis in high-complexity and low-information-theory environments (Hair et al., 2019). While PLS-SEM has indicators that maximize the explained variance and are oriented toward prediction, covariance-based structural equation models aim to explain the fit based on the goodness of fit of a model to interpret the observations of different measurements performed through analysis of variance and covariance (Hair et al., 2019). PLS aims to avoid collinearity problems and the non-assumption of hypotheses regarding the distribution of variables (Henseler & Schuberth, 2020). Data processing using PLS-SEM first involves analyzing the reliability and validity of the measurement model (Chin, 1998). Second, we evaluated the structural model to test the hypotheses that answered the research questions.

4Results4.1Assessment of measurement scalesAssessment of the measurement model of the estimated constructs involved analyzing the individual reliability of its indicators observed through their loadings and the reliability of the latent variables through Cronbach's alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). The evaluation of the measurement model requires others to analyze convergent validity through AVE and discriminant validity through the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (Hair et al., 2019). For the values of the loadings of the individual indicators and CA, values above 0.7 (Hair et al., 2018) are recommended. CR values higher than 0.6 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988) or 0.7 (Chin, 2010) and AVE values greater than 0.5 are suggested (Chin, 2010). For discriminant validity analysis, HTMT ratio values lower than 0.90 are suggested by Kline (2015). Table 2 shows that all indicators met the required thresholds; thus, they showed good fit reliability, validity, and discriminant validity.

Convergent validity and reliability and discriminant analysis.

The second step involved the evaluation of the structural model. An analysis of collinearity of the structural model was performed using the invariance inflation factor (VIF) and the statistical significance of the effects of the path coefficients. Table 3 shows VIF values lower than 3.3 (Hair et al., 2019), so problems related to this indicator were ruled out. Similarly, the standardized betas and t-values confirm the significance of the established relationships.

VIF and hypothesis testing (mains effects).

| Relationship | VIF | Standardized beta | T-value | f2 | Accepted / Rejected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. Country of origin leg. → Organizational legitimacy | 1.298 | 0.617⁎⁎⁎ | 5.332 | 0.17 | Accepted |

| H2.a. Consumer information → Country of origin leg. | 1.000 | 0.479⁎⁎⁎ | 8.772 | 0.30 | Accepted |

| H2.b. Consumer information → Organizational leg. | 1.298 | 0.498⁎⁎⁎ | 9.395 | 0.13 | Accepted |

| H3. Consumer information → Purchase intention | 1.298 | 0.552⁎⁎⁎ | 11.868 | 0.14 | Accepted |

| H4. Organizational legitimacy → Purchase intention | 1.330 | 0.558⁎⁎⁎ | 12.573 | 0.51 | Accepted |

Country of origin legitimacy: R2 = 0.23; Q2 = 0.13; Organizational legitimacy: R2= 0.54; Q2 = 0.49; Purchase intention: R2 = 0.490; Q2 = 0.30.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Table 3 presents the hypothesis testing results using 5000 subsamples. In relation to H1, the legitimacy of the country of origin has a positive and significant influence on legitimacy (H1: β=0.617; p<0.000). The effect of consumer information is positive and direct for all three hypotheses: consumer information influences country of origin legitimacy (H2a: β=0.479; p<0.000), with a similar impact as on organizational legitimacy (H2b: β=0.498; p<0.000). Likewise, consumer information directly influences purchase intention (H3: β=0.552; p<0.000). Finally, organizational legitimacy positively and significantly influences purchase intention (H4: β=0.558; p<0.000).

Regarding the explanatory power of the model, on the one hand, the R2 values of 0.423 (country of origin legitimacy), 0.54 (organizational legitimacy), and 0.49 (purchase intention) indicate a substantial predictive effect of the hypotheses proposed. In contrast, the Stone-Geisser value (Q2) evaluates the predictive relevance of the dependent construct. Values of Q2 greater than zero indicate that the model has predictive capacity. As shown in Table 3, values of 0.128 (country-origin legitimacy), 0.238 (organizational legitimacy), and 0.391 (purchase intention) were obtained, indicating that the model had predictive capacity. Finally, the coefficient f2 evaluates the effect of an exogenous variable on explaining an endogenous variable in terms of R2. The guidelines for assessing f2 values higher than 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 depict small, medium, and large f2 effect sizes (Hair et al., 2019). Table 3 shows that the effect of organizational legitimacy on purchase intention is significant. The effect of the relationships among the other variables in the model was moderate.

5ImplicationsThis study analyzes the effect of the legitimacy of the country of origin on the legitimacy of EMNEs in host countries. In addition, the role of consumer information on the country-of-origin legitimacy and the legitimacy of EMNEs is quantified. Finally, we measure the impact of both the legitimacy of EMNEs and consumer information on the purchase intention of host consumers. The results of the hypothesis tests confirmed all relationships. Improving purchase intention during internationalization requires EMNEs to devote effort to managing consumer information, legitimacy, and the impact of the legitimacy of their home country.

On one hand, this research demonstrates that country-of-origin legitimacy in our empirical study of China directly and positively impacts organizational legitimacy (Hypothesis 1). If the home country norms differ from those of the host country, the legitimacy of EMNEs in these countries will be conditional (Paule-Vianez et al., 2021). EMNEs are affected by the halo effect (Calvo-Iriarte et al., 2023) generated by the legitimacy of their countries. Academically, this research is pioneering in measuring the impact of country-of-origin legitimacy on organizational legitimacy. Previous researchers have shown how EMNEs must develop legitimacy strategies to enter new markets (Jiang et al., 2022; Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022) as well as the need to adapt, for example, to cultural standards to gain legitimacy (Javadian et al., 2021). This study advances the legitimacy literature by quantifying the direct and positive impact of country-of-origin legitimacy on the legitimacy of EMNEs.

This study also demonstrates the impact of consumer information on country-of-origin legitimacy, organizational legitimacy, and purchase intention. Several authors, such as Bitektine (Bitektine, 2011) and Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2022), have analyzed the importance of active cognitive processing, knowledge, information search efforts, and social interactions as antecedents of legitimacy insofar as legitimacy is a perception and its formation is based on prior information (Blanco-González et al., 2023) and a series of social and individual beliefs (Haack et al., 2022). Marketing and business management scholars are aware that the information processed by consumers affects the sales or image of a company (Hu et al., 2020). In the case of EMNEs, consumer information has a direct and significant impact on the company because it reduces the uncertainty generated by the arrival of new companies in the host country (Bai et al., 2019). The impact of consumer information on country-of-origin legitimacy, organizational legitimacy, and purchase intention in EMNEs suggests the need to explore strategies to manage and control the information transmitted from and by these companies, as this can create an advantage or disadvantage when entering new markets. This finding also points to the need for public-private collaboration so that countries' foreign trade policy efforts reinforce information on the characteristics and strengths of the products of the country of origin.

This study provides new empirical evidence on the relationship between organizational legitimacy and purchase intention. Previous research (Miotto & Youn, 2020; Payne et al., 2021; Valor et al., 2021) has shown that, if consumers perceive that a company complies with institutional norms, they are willing to grant legitimacy, support their activities within society, and maintain long-term relationships. This research goes a step further by demonstrating the extent to which it is important for EMNEs to legitimize themselves to achieve sales, generate alliances with partners in host countries, and survive in international markets.

The relationships between variables were tested in the fast fashion sector in a developed country, in which EMNEs from other countries are regular competitors and where consumers, governments, and companies endure the tension between sustainability and low prices. The Chinese EMNE Shein has also been selected as one of the fastest growing EMNEs in this sector, occupying the market position that traditional fast fashion companies are abandoning in favor of a more sustainability-oriented strategy. At this point, it is important to ask whether consumers really want sustainable brands or whether they are more interested in the prices of products. These results show that it is necessary to academically test whether sustainability policies and adaptation to the SDGs of companies in the fast fashion sector respond to the demands of consumers in this sector or if, instead, it is the gateway for EMNEs that identify that there is a segment and, despite valuing sustainability, are driven by price as the determining factor (Zhang et al., 2022).

Furthermore, from the perspective of business management, this research suggests that managers should bear in mind that information is a determining factor of legitimacy. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of communication in the legitimacy of organizations (Prado-Roman et al., 2020). In this case, EMNEs have to consider what information the new market´s customers have about the new company and its country of origin because both aspects influence the legitimacy of the EMNE. Knowledge about the new market is a key element, and foreign companies need to understand the differences that exist with respect to the country of origin in the process of internationalization market demand (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). This involves identifying sources of information on the characteristics of the local market, managing the information, and transforming it into useful proposals for a new market (Gnizy, 2019). Better knowledge of new consumers will help establish appropriate communication channels to be closer to the target audience, which positively influences their opinion about the new foreign company (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). Moreover, it is essential for governments to intensify internationalization programs in which the country brand is positioned with respect to potential international markets.

The results suggest that managers' actions aimed at adapting to the values and social norms of host countries—that is, legitimizing themselves—will have an impact on the sales of EMNEs. Companies perceived as legitimate are more likely to access the required resources and enter new markets with fewer restrictions (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2023). These results are in line with previous research indicating that EMNEs that act in accordance with the values of developing countries obtain better legitimacy levels (Del-Castillo-Feito et al., 2021). Consumers are generally attracted to companies that focus on social issues (Blanco-González et al., 2020). If EMNEs, particularly in the fast fashion sector, provide more transparent information about their production processes without renouncing profits by maximizing market share, they can manage to increase their legitimacy, which, in turn, will impact their sales. Finally, it should be noted that this study was conducted on a company that markets products online. Therefore, managers should consider that intelligent management of information transmitted by a company and strengthening legitimacy can increase consumer engagement.

The main limitations of this study lie in focusing on a single EMNE of Chinese origin in a specific sector (Shein) and not considering other companies in this sector, personal sales, or another country of origin. This study focuses on Chinese EMNEs, which, as the literature has identified (Yang et al., 2022), face greater barriers derived from their country of origin in some countries. These limitations have led us to propose new lines of research. Future research should include EMNEs from other sectors, sales channels, and origins. By gathering this information, we will be able to conduct comparative studies to develop strategies for managing the legitimacy of the country of origin and of enterprises to reduce barriers to entry and survival in host countries, generate engaged relationships with consumers, and legitimize themselves as any other company. In addition, future lines of research include the development of a theoretical framework on how information processing impacts organizational legitimacy (Díez-Martín et al., 2021a), how the Multilevel Theory of Legitimacy (Haack et al., 2021) impacts the legitimacy of countries of origin and EMNEs, and how the ethical behavior of brands impacts legitimacy and helps EMNEs enter new markets.

Any interest or relationship, financial or otherwise, that might be perceived as influencing an author's objectivity is considered a potential source of conflict of interest.