In today's business environment, management of knowledge-intensive workers has become one of the most challenging elements to consider. To sustain a company's competitive advantage, highly skilled workers who are perfectly aligned and motivated in the organization are essential. However, happiness becomes essential for these type of employees. Happiness at work is a research topic that is growing in importance among academics, but requires further attention. Through a narrative synthesis method, we review, clarify and suggest future research lines to develop research on happiness at work in knowledge-intensive contexts.

It was Drucker (1959) who introduced the concept of knowledge-intensive workers, and since then the management of human resources has received increased attention. The ideas of knowledge-intensive companies, knowledge-intensive workers and knowledge-intensive contexts are difficult to separate, as all organizations and work require knowledge (Alvesson, 2001). Most knowledge is tacit and exists in the head of individuals (Polanyi, 1967), but the process of exchanging, combining, generating and acquiring external knowledge can be managed (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Different perspectives on knowledge management highlight that integrative complexity needs an effective atmosphere (Kogut & Zander, 1992), such as the affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). This paper focuses on knowledge-intensive workers, namely workers with the capacity to solve complex problems through creative and innovative solutions (Hedberg, 1990). Managing knowledge-intensive workers to reach organizational objectives is a difficult managerial aspect. Knowledge-intensive workers create, use and share knowledge, making them decisive to the success of their company, although some issues on how to best manage knowledge-intensive workers persist. Managers of knowledge-intensive companies normally fall into one of two types: scientists that have reconverted to become managers, or executives who have reached the scientific field with no research experience. The former managers conceive employees as equals, and the latter treats them as unskilled employees. The result is that workers become disappointed and unmotivated. Managers need to understand the needs and motivations of knowledge-intensive workers, as they are the basis of any firm's competitive advantage (Milne, 2007). However, this type of worker presents different characteristics and levels of output compared to normal personnel, and therefore needs different managerial approaches (Alvesson, 2001). The main issue concerning knowledge-intensive workers is to attract and retain them, generating commitment and loyalty. The motivation of intensive-knowledge workers becomes crucial for management (Boddy, 2008).

Knowledge-intensive workers need social interactions to communicate, collaborate and brainstorm with their intellectual peers. They also need to be treated as being different from other colleagues, in order to feel fully valued as being unique, and not merely as an interchangeable resource. They need their research projects to be customized according to their passions and skills, and closely matched to their main interests. Shaping a context that improves knowledge-intensive employees’ happiness at work might lead them to feel motivated. It is crucial for knowledge-intensive workers to feel happy at work for them to perform at their best. Nevertheless, there is still debate on exactly what is happiness at work and how helpful it could be in the work context (Barrena-Martínez, López-Fernández, & Romero-Fernández, 2017; Luthans & Avolio, 2009; Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, Alegre, & Fernández, 2017; Vila-Vázquez, Castro Casal, & Álvarez Pérez, 2016). In this sense, the number of positive attitudinal concepts in this field has greatly increased in recent years (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017). For example, a narrative review examined the concept of engagement, revealing an increasing interest in the positive attitudes’ field of research (Bailey, Madden, Alfes, & Fletcher, 2017). Job satisfaction, engagement, commitment and well-being, among others, are central concepts in positive attitude research that aims to improve an employee's quality of life at work. The aim of this paper is to advance knowledge on happiness at work, at individual level, based on Fisher's (2010) work, yet focusing on knowledge-intensive workers. In the following pages, we set forth the following questions about happiness at work:

- (1)

What are the key positive attitudinal constructs related to happiness at work?

- (2)

How can we define happiness at work?

- (3)

What are the antecedents and consequences of happiness at work?

- (4)

What are the future required research lines?

This paper is organized as follows. First, the methodological approach is described. Next, the concepts related to positive attitudes and happiness at work, as well as the main theoretical approaches to explain positive attitudes at work in knowledge-intensive contexts are reviewed. Then, the findings regarding to the antecedents and outcomes of happiness at work are presented. Finally, the conclusions and suggestions for practice are explained.

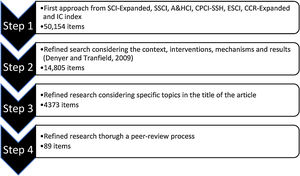

2Research methods2.1Data collectionThis paper used a narrative evidence synthesis method in line with the principles of organization, transparency, replicability, quality, credibility and relevance. We followed a five-step systematic review (Suárez, Calvo-Mora, Roldán, & Periáñez-Cristóbal, 2017) defined by Briner and Denyer (2012). Narrative synthesis is an accurate method to analyze the story grounded in a diverse body of research, by giving reviewers the chance to generate ideas that give consistency to the data (Briner & Denyer, 2012). This method is driven by a set of principles rather than a single rigid protocol: planning, structured search, evaluation of the material against agreed eligibility criteria, analysis and thematic coding, and reporting. The wide diversity of concepts related to positive attitudes makes this method particularly appropriate in this case. Evidenced-based and systematic reviews are an efficient way of understanding what we know and what we do not know about a specific topic (Briner & Denyer, 2012). In healthcare research it is a well established method, and we are convinced that it offers considerable value to management researchers.

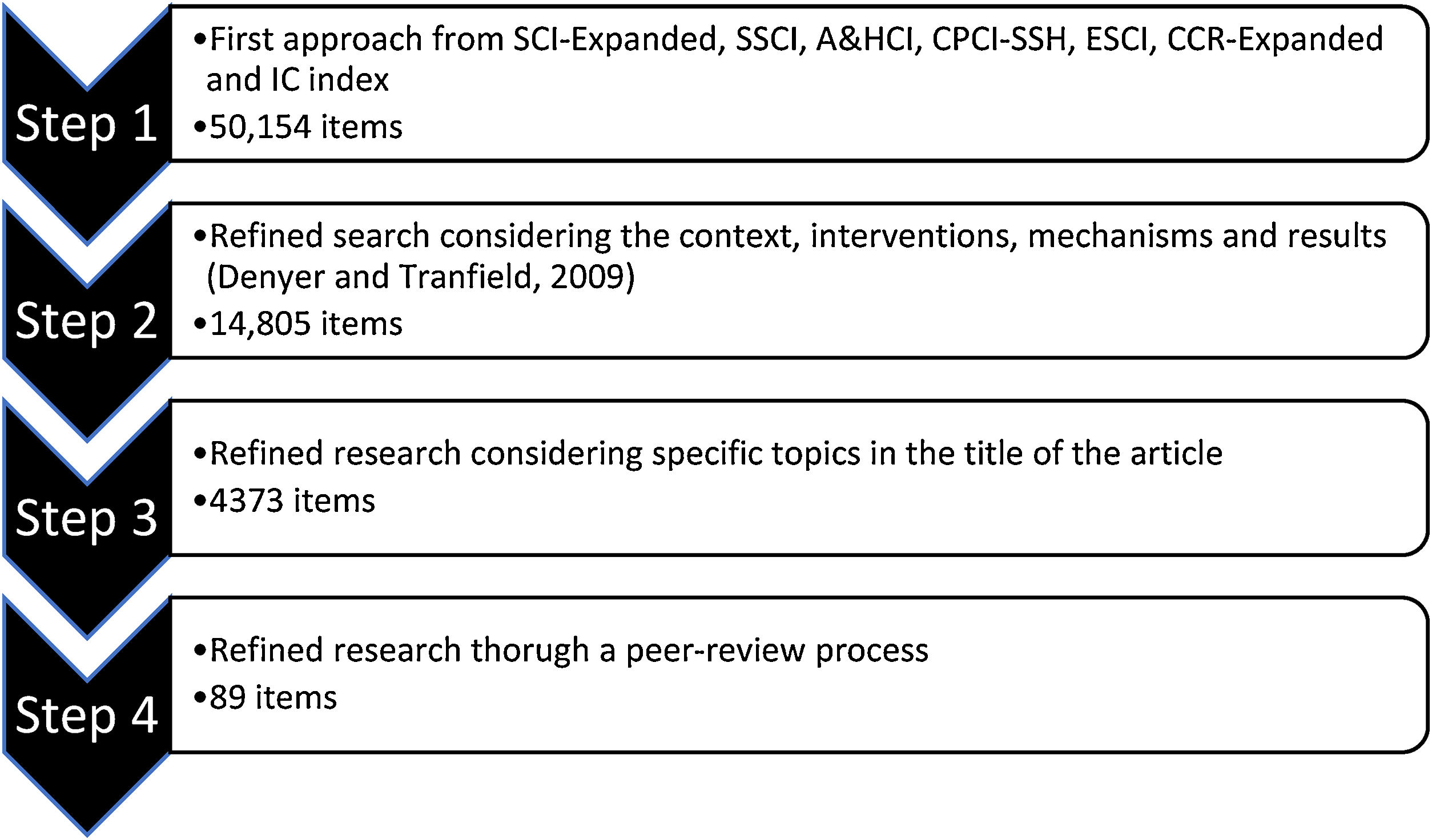

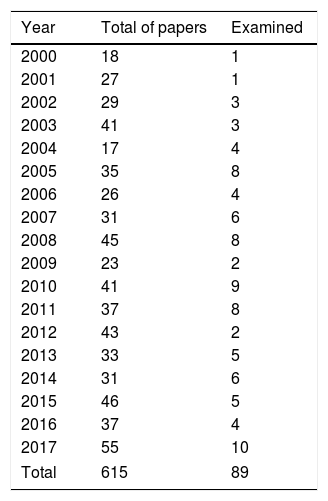

A first open-search approach brought 50,154 items from SCI-Expanded, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-Expanded and the IC index. Then, we produced and refined an inclusive long string of appropriate search terms belonging to diverse disciplinary fields, using the CIMO framework (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). For this purpose, we considered the research questions regarding the context in which data was collected, the interventions being assessed, the mechanisms through which the interventions would generate outcomes, and the outcomes as perceptible results. Taking this groundwork into account, we delimitated our search to items written in English, and published since 2000, when Seligman's article of positive psychology was published. This paper was cited 3162 times in the Web of Science Core Collection. The refined search generated 14,805 items.

A group of experts, consisting of senior professors with broad research experience in the management field, and specialized in positive attitudes, set the following topics: ‘happiness at work’ OR ‘employee happiness’ OR ‘work happiness’ OR ‘job happiness’ OR ‘organizational happiness’ OR ‘staff happiness’ OR ‘engagement’ OR ‘job satisfaction OR ‘commitment’, ranging from January 2000 to December 2017. The search criteria were defined so that at least one of these terms had to appear in the title of the research paper. This structured search produced a total of 4373 results from the seven databases. The abstracts were first evaluated by two new research experts, who determined their quality and relevance, starting from the most cited papers in each year (Web of Science can order the results by the number of citations). A rating was used to assess papers that had been subject to a peer-review process, were written in English, produced since 2000, framed in knowledge-intensive workers, classified in the management field, dealt with the study of employees, or were theoretical items that presented significant information on the definition of happiness at work. In addition, the abstracts of each of these papers were evaluated again by two experts using previously established quality and significance criteria to reduce selection bias (Briner & Denyer, 2012). At this stage, 4284 items were removed, leaving 89 items to be considered (Fig. 1).

2.2Data analysisWe followed the method of Popay et al. (2006), who suggested that a narrative synthesis should aim to examine the connections in the selected data within and between studies. In line with Nijmeijer, Fabbricotti, and Huijsman (2014), we first explored the main design characteristics of each piece of research and the implementation of the variables affected. Then, we generated factor clusters and produced sub-clusters through thematic examination. Of the 89 considered items, 10 were conceptual, 73 used empirical data and six were meta-analyses. 22 papers evaluated relevant outcomes, nine examined mediation effects, and 58 focused on key antecedents.

3Definitions and theories of happiness at work3.1DefinitionsThe literature as a whole revealed that definitions of happiness in the work context could be classified in the following main groups: job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, hedonia and eudaimonia, well-being, psychological capital and happiness at work.

3.1.1Job satisfactionLocke (1976) defined job satisfaction as a “positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job or job experiences”. Through the happy-productive worker model, job satisfaction has been connected to job performance (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Job satisfaction is a central concept in the management field (Chiva & Alegre, 2009), and refers to judgements about job characteristics, such as job conditions and opportunities (Moorman, 1993). This is the main difference compared to engagement, which refers to feelings of energy and passion at work (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017).

3.1.2EngagementThe concept of engagement has expanded because of its importance for positive implications in organizations (Extremera, Sánchez-García, Durán, & Rey, 2012). Kahn (1990) defined engaged employees as those who employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, emotionally and mentally during role performances, giving themselves to their work. Macey and Schneider (2008) defined engagement as feelings of persistence, vigor, energy, dedication, absorption, enthusiasm, alertness and pride.

Engaged employees enhance customer loyalty (Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2005), and make extra efforts toward success (Meyer & Janney, 1989).

3.1.3CommitmentEmployee commitment refers to the level of connection with an organization (Meyer & Allen, 1997), and comprises three dimensions: affective, continuance and normative commitment. Affective commitment is related to emotional links, identification and involvement in the organization (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002). Continuance commitment refers to the perceived costs to the employee if she or he leaves the organization (Meyer & Allen, 1984). Normative commitment is the obligation the employee feels to stay in the organization (Allen & Meyer, 1990). The terminology of engagement and commitment literature is confused by their interchangeable use (Mowday, 1998), but there are clear differences between them (Hallberg & Schaufeli, 2006). Both concepts refer to positive attachment to work, and have reciprocal theoretical references to each other. Engagement refers to “optimal functioning” at work in terms of well-being. Engagement is related to experiencing passion, energy, absorption (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002). In contrast, commitment, and particularly affective commitment, is more dependent on job characteristics than personal factors. Affective organizational commitment concerns attitudes toward the organization.

3.1.4Hedonia and eudaimoniaHedonia refers to feelings of pleasure, and can be defined as the positive feelings that accompany getting the material objects one wants or having the action opportunities one wishes for (Waterman, Schwartz, & Conti, 2008). Eudaimonia refers to living well or actualizing one's human potentials (Waterman, 1993). It is understood as a process of fulfilling one's virtuous potentials (Waterman et al., 2008).

3.1.5Well-beingTwo divergent positions represent the concept of well-being. Ryff (1989) understands well-being as ‘psychological well-being’ (PWB). This concept is related to the eudaimonic aspects of happiness, comprising six dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, and autonomy (Ryff, 1989). Other approaches capturing only eudaimonic aspects are the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), flourishing (Keyes, 2002), authentic happiness (Seligman, 2002), self-realization (Waterman, 1993) and flow (Vittersø, 2003). In contrast, Diener defines well-being as subjective well-being (SWB), which is widely accepted in academic literature (Kashdan, Biswas-Diener, & King, 2008), and captures both eudaimonic and hedonic aspects of happiness at work.

3.1.6Psychological capitalPsychological capital (PsyCap) is a higher-order construct that comprises four dimensions: optimism, efficacy, resiliency and hope. PsyCap can be considered as a personal resource (Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009) that facilitates job satisfaction (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, 2007), and therefore it might be an antecedent of positive attitudes, such as well-being and engagement (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017). PsyCap is a state-like construct, which differentiates it from other positive psychological constructs. State-like constructs are more malleable and open to development (Luthans et al., 2007).

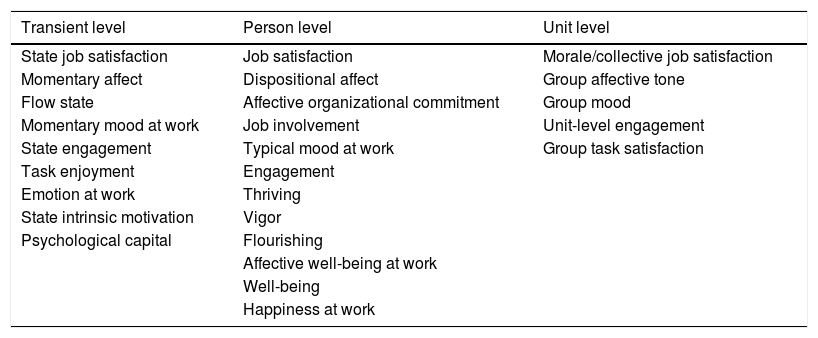

3.1.7Happiness at workPositive psychology is defined as ‘a science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions’ that aims to improve quality of life (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5). It is related to well-being, contentment and happiness, focusing on the positive aspects of human beings, rather on negative aspects. Under the perspective of positive psychology, people are motivated to maximize their positive experiences in everyday circumstances. First, we need to define what being positive means, or what a good life as (Waterman, 2007). The two main approaches of well-being are the hedonic and the eudaimonic points of view (Ryan & Deci, 2001). While well-being has been widely considered in academic research, the review made in this paper reveals that happiness has not been extensively used among scholars, at least in the workplace context. Paradoxically, there is clear evidence that researchers are interested in the concept of happiness at work (Fisher, 2010). Several concepts seem to overlap with the notion of happiness at work, as shown in Table 1. The individual level represents the largest number of constructs related to happiness at work. The main constructs examined include job satisfaction, engagement and commitment. At the transient level, happiness at work-related constructs vary at the within-person level, representing short-lived moods and emotions that individuals might experience. Unit-level happiness at work constructs are focused on teams and organizations. They are usually captured by aggregating the personal experiences of individuals in the collective. In this research, we focus on an individual level of analysis.

Literature has observed an excessive number of concepts surrounding happiness at work (Warr, 2007), some of which overlap each other (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012). Harrison, Newman, and Roth (2006) began the development of a higher-order construct to capture wide positive attitudes, by means of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and following Fisher (2010) suggested a three-dimension construct including the job itself, the job characteristics and the organization as a whole. Pan and Zhou (2015) suggested that happiness at work should be widely measured by means of two constructs, a global happiness approach and the positive affect and negative affect scale. Later, Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al. (2017) took up the baton and conceptualized and measured happiness at work (HAW) among knowledge-intensive workers, through engagement, job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment.

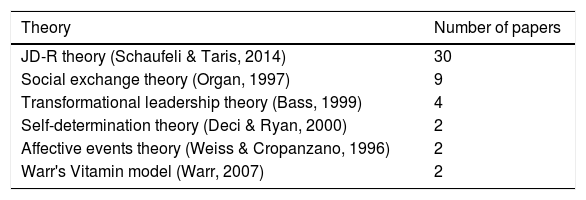

3.2Theoretical frameworksThe predominant theoretical framework of the papers examined to explain happiness at work and its related concepts is the Job Demands-Resources theory (JD-R) (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). 30 papers from a total of 89 were based on this theory, which argues that job resources, or the physical, psychological, social, or organizational characteristics of a job promote positive attitudes and positive behaviors, while job demands and lack of resources (such as lack of support from supervisors) result in negative states. Job resources might be particularly important in knowledge-intensive contexts, as employees need considerable general support for their complex tasks. Different resources have been considered to promote happiness at work and other positive attitudinal concepts. For example, transformational leadership has been revealed to act as a resource that promotes happiness at work (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017) and organizational commitment (Muchiri, Cooksey, & Walumbwa, 2012).

The Social Exchange Theory (Organ, 1977) shows through reciprocity norms how happier employees contribute more to the organization, as they relate their happiness to the organization. This theory was found in 8 of the examined papers, and argues that employees are motivated within the employment relationship to exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors when they understand that their employer values them (Kuvaas & Dysvik, 2010). These performance-enhanced spirals include self-efficacy, effort and rewards (Locke & Latham, 1990). Some studies argue that positive attitudes might mediate the relationship between HRM practices and performance, based on the Social Exchange Theory (Alfes, Shantz, Truss, & Soane, 2013; Alfes, Truss, Soane, Rees, & Gatenby, 2013).

The transformational leadership theory was used to develop 4 research papers, showing that this leadership style improves job satisfaction among academics (Braun, Peus, Weisweiler, & Frey, 2013), commitment among professionals (Muchiri et al., 2012) and nurses (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004), and demonstrated that transactional leadership has a weak effect on positive attitudes (Berson & Linton, 2005).

In addition, the self-determination theory helps to explain how individuals become happier in knowledge-intensive contexts. Basically, the self-determination theory is a general human motivation theory that describes the degree to which individuals are self-motivated (Deci & Ryan, 2000). This theory suggests that greater competence, autonomy and relatedness lead to higher motivation (Sheldon, Ryan, & Reis, 1996). Two papers were found to follow this theory. For example, Wright (2014), following this theoretical framework, argued that happiness improves job performance among R&D professionals.

Similarly, the affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996) argues that stable characteristics of work designs, for instance, organizational practices, produce momentary pleasant experiences, such as job satisfaction (Fisher, 2000). We argue that individuals that work under cognitive demanding tasks need stable work designs at work. Two papers followed this theory (Basch & Fisher, 2000; Rezvani et al., 2016).

Finally, Warr's Vitamin model (Warr, 2007) states that job characteristics can act as vitamins fostering well-being up to a recommended level, from which additional amounts are thought to have limited positive effects on happiness. Two papers, Horn, Taris, Schaufeli, and Schreurs (2004) and Wright, Cropanzano, and Bonett (2007), followed Warr's Vitamin model, explaining that autonomy positively affects well-being, and that control, skill use, variety, environmental clarity, equity, valued social position, pay and career issues are positively related to happiness at work. The remaining papers used a diverse range of theories which are less frequently used. Table 2 details the theoretical framework of the research papers found in knowledge-intensive contexts.

Concepts related to happiness at work (own development and Fisher, 2010).

| Transient level | Person level | Unit level |

|---|---|---|

| State job satisfaction | Job satisfaction | Morale/collective job satisfaction |

| Momentary affect | Dispositional affect | Group affective tone |

| Flow state | Affective organizational commitment | Group mood |

| Momentary mood at work | Job involvement | Unit-level engagement |

| State engagement | Typical mood at work | Group task satisfaction |

| Task enjoyment | Engagement | |

| Emotion at work | Thriving | |

| State intrinsic motivation | Vigor | |

| Psychological capital | Flourishing | |

| Affective well-being at work | ||

| Well-being | ||

| Happiness at work |

As knowledge intensive workers rely on their own judgment and work both independently or with peers (Alvesson, Blom, & Sveningsson, 2016), it seems that this theory is accurate for knowledge-intensive workers. However, these theories should be interpreted with caution. Some papers did not specify theories, and the underlying theory was not clear, whilst in other papers, we inferred theories based on the information provided. In any case, we have only reported the main theoretical frameworks (Table 3).

Most frequent theoretical frameworks in knowledge-intensive contexts.

| Theory | Number of papers |

|---|---|

| JD-R theory (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014) | 30 |

| Social exchange theory (Organ, 1997) | 9 |

| Transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1999) | 4 |

| Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) | 2 |

| Affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996) | 2 |

| Warr's Vitamin model (Warr, 2007) | 2 |

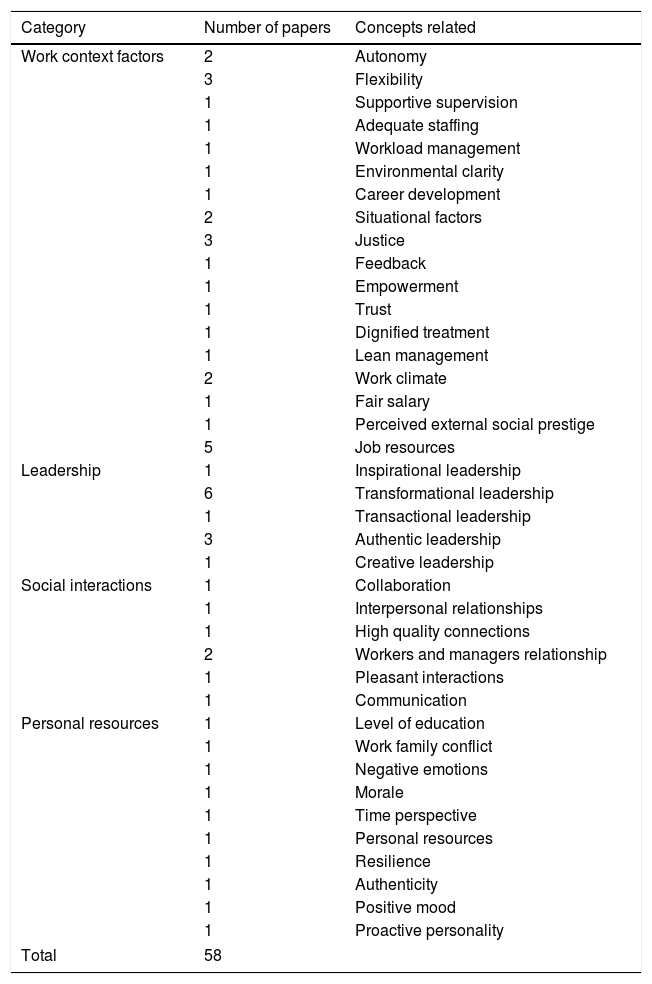

Fifty-eight empirical papers examined the antecedents of happiness at work at individual level. These papers were the results of the narrative synthesis method, as explained in section 2.2. We have grouped these results under four headings: work context factors, leadership styles, social interactions, and personal resources. Three underlying theories prevailed among these papers: the job demands-resources theory, the social exchange theory and Warr's Vitamin model. It is important to highlight that work context factors (i.e. Gevrek, Spencer, Hudgins, & Chambers, 2017) and personal resources (i.e. Tarcan, Tarcan, & Top, 2017) cover most of the recently published papers (between 2015 and 2017, five papers for each category) while we must go back to the year 2010 to find the most recent paper which can be grouped under the social interactions category (Hayes, Bonner, & Pryor, 2010) (Table 4).

Paper category, number of papers in the category and concepts related to positive attitude antecedents.

| Category | Number of papers | Concepts related |

|---|---|---|

| Work context factors | 2 | Autonomy |

| 3 | Flexibility | |

| 1 | Supportive supervision | |

| 1 | Adequate staffing | |

| 1 | Workload management | |

| 1 | Environmental clarity | |

| 1 | Career development | |

| 2 | Situational factors | |

| 3 | Justice | |

| 1 | Feedback | |

| 1 | Empowerment | |

| 1 | Trust | |

| 1 | Dignified treatment | |

| 1 | Lean management | |

| 2 | Work climate | |

| 1 | Fair salary | |

| 1 | Perceived external social prestige | |

| 5 | Job resources | |

| Leadership | 1 | Inspirational leadership |

| 6 | Transformational leadership | |

| 1 | Transactional leadership | |

| 3 | Authentic leadership | |

| 1 | Creative leadership | |

| Social interactions | 1 | Collaboration |

| 1 | Interpersonal relationships | |

| 1 | High quality connections | |

| 2 | Workers and managers relationship | |

| 1 | Pleasant interactions | |

| 1 | Communication | |

| Personal resources | 1 | Level of education |

| 1 | Work family conflict | |

| 1 | Negative emotions | |

| 1 | Morale | |

| 1 | Time perspective | |

| 1 | Personal resources | |

| 1 | Resilience | |

| 1 | Authenticity | |

| 1 | Positive mood | |

| 1 | Proactive personality | |

| Total | 58 | |

Many of the studies on happiness at work among knowledge-intensive workers examine how complex and challenging contexts affect employee happiness. For example, the opportunity for skill use, variety, environmental clarity, equity, valued social position, pay and career issues are positively related to happiness at work (Warr, 2007). Dignified treatment, fairness, pride in the company and camaraderie with colleagues make employees happier (Sirota, Mischkind, & Meltzer, 2005). A multilevel approach (De Koeijer, Paauwe, & Huijsman, 2014) also revealed that lean management improved healthcare professionals’ happiness at work.

Autonomy is particularly relevant for knowledge-intensive workers. Heijstra and Jónsdóttir (2011) examined how autonomy positively affects physicians’ well-being.

Maslach and Leiter (1997) highlighted the effects of autonomy on employee burnout. The job-strain model (Karasek, 1979) clearly explains how autonomy is necessary for jobs involving high demands, such as the knowledge-intensive workers context. This model states that a context with high demands and low control causes strain. On the contrary, jobs with high control generate low job-strain levels. Again following Warr's Vitamin model, Horn et al. (2004) showed that autonomy, understood as the degree to which people can resist environmental demands and follow their own opinions and actions, significantly affects well-being at work. Following the job demands-resources model, it was found that job resources promoted engagement among Dutch teachers (Bakker & Bal, 2010), job demands lead to burnout among physicians (Hakanen, Schaufeli, & Ahola, 2008), job resources improved engagement and helped to cope with job demands among Finnish teachers, (Bakker et al., 2008; Georgellis and Lange, 2007), and organizational support and justice predicted affective commitment among nurses (Sharma & Dhar, 2016). Implicitly, under the JD-R theory, the perceived organizational climate has also been related to satisfaction and commitment (Carr, Schmidt, Ford, & DeShon, 2003). These contexts that make individuals perceive the employment of their unique personal strengths generate positive attitudes (Seligman, 2005). Flexible working might also promote employee happiness. Golden and Veiga (2005) revealed that telecommuters, employees who can work outside their job location, adjust work activities to meet their own needs and balance work and family responsibilities. Employees who can control their work time experience higher levels of well-being at work (Berg, Applebaum, Bailey, & Kalleberg, 2004). This control over work is considered as a primary feature to promote happiness at work (Warr, 2007). In a case study, Atkinson and Hall (2011) revealed how flexible working positively affects employee happiness. As a result, worker flexibility has been proved to decrease stress levels and increase work well-being (Golden & Veiga, 2005).

Several studies found a relationship between leadership style and positive attitudes or happiness at work. Between 2015 and 2017, two papers evidenced the role of leadership in improving positive attitudes: inspirational leadership and transformational leadership positively affected medical specialists’ happiness at work (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017; Salas-Vallina & Fernandez, 2017). Creative leadership has also been found to facilitate others’ innovative thinking (Basadur, 2004). Authentic leadership was related to eudaimonic well-being, but most studies framed in knowledge-intensive contexts link transformational leadership and well-being. Interestingly, Braun et al. (2013) performed a multilevel analysis among academics and found that transformational leadership and trust in the supervisor promoted job satisfaction. Conversely, transactional leadership styles had a weaker effect on positive attitudes, according to Berson and Linton (2005). Considering the above review, it seems clear that strategic competencies, such as inspiration, have a stronger impact on workers with high cognitive tasks, compared with those who perform more mechanical tasks. Employees who need more reflection at work, give more value to leaders that provide them with higher autonomy, opportunity of growth and recognition.

Another source of happiness at work might be social interactions with other people. Past research has evidenced the essential role of interpersonal relationships in fostering happiness and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). We found that high-quality connections with others provide happiness and energy to employees (Dutton & Ragins, 2007). Pleasant interactions with others are also related to pleasant emotions (Basch & Fisher, 2000). Thompson and Heron (2005) revealed that the perceived quality of the relationship between knowledge workers and their manager can make a positive difference in the context of any breach of the psychological contract and this, in turn, can help maintain levels of commitment, which are important for knowledge creation. Hayes et al. (2010) found that collaboration among nurses and their managers was crucial to increase job satisfaction. Human being needs contact with others, but it seems that social interactions are particularly relevant for knowledge-intensive workers. This type of employees needs to share knowledge and exchange ideas to develop their knowledge. It would also seem logical that employees who feel socially detached at work might present feelings of dissatisfaction. By getting to know colleagues, workers can better understand each other and, as a consequence, work tasks become more effective in a more satisfying environment. People do not leave their job because of the company, but as a consequence of the social relationships at work.

It would also seem that personal resources have a direct impact on positive attitudes. The level of education among healthcare professionals significantly affected job satisfaction (Tarcan et al., 2017) and communication improved affective commitment in the same context (Tekingündüz, Top, Tengilimoğlu, & Karabulut, 2017). Resilience was found to improve nurses’ job satisfaction (McVicar, 2016) and positive moods promoted engagement among software developers (Bledow, Schmitt, Frese, & Kühnel, 2011). In an essential paper, Macey and Schneider (2008) argued that a proactive personality predicts work engagement.

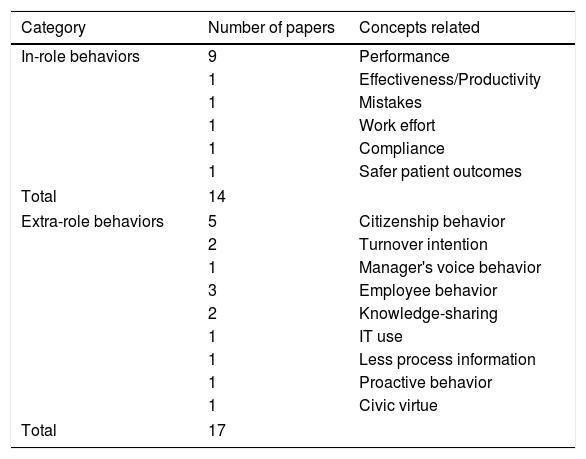

5Outcomes and mediation effects of happiness at workAn essential question to ask is whether individuals should improve their happiness at work. What are the expected benefits from happier employees in the job context? Using 22 outcome and 9 mediation papers from the narrative synthesis method used, we explored the consequences of happiness at work based on two main ideas: in-role performance behaviors and extra-role performance behaviors. The social exchange theory, JD-R theory, self-determination theory and positive organizational theory prevailed in these papers.

The relationship between positive attitudes, such as job satisfaction, and individual job performance has been defined as the ‘Holy Grail’ of research on organizational behavior (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Job performance can be defined as behavior that is under individual control and that has an effect on the objectives of the organization (Campbell, 1990). This relationship has been confirmed in strong meta-analyses. For example, Harrison et al. (2006) meta-analysis confirmed the predictive capacity of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on focal job performance (in-role performance) and contextual performance (extra-role performance). Interestingly, our review found that jobs in which knowledge is fundamental, present a clearer connection between positive attitudes and performance. In particular, Judge, Thoresen, Bono, and Patton (2001) showed that job complexity significantly moderated the job satisfaction-performance link, with a high relationship of 0.52 in highly complex jobs (job satisfaction is one dimension of HAW). Job satisfaction is an essential, widely accepted positive attitude which is close to HAW, and incorporates both cognitive and affective elements, and is a response to the “perception” of job characteristics (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017).

Routine or “Taylorist jobs”, with a fixed pool of inputs, have been considered to be positively related to in-role performance, and negatively related to extra-role performance (Hunt, 2002). Nevertheless, less routine, less rigidly defined jobs, such as knowledge-intensive jobs, can produce positive connections between in-role and extra-role performance (Harrison et al., 2006).

The relationship between job attitudes and job performance (both in-role and extra-role performance) follows the key principles of social psychologists. Fisher (1980) and Hulin (1991) argued that job attitudes do not accurately predict job behaviors because attitudes are defined with different criteria than those of behaviors (Harrison et al., 2006). This phenomenon is known as the ‘compatibility principle’ (Ajzen, 1988), and aims to respond to controversy in social psychology in predicting behaviors. Harrison et al. (2006), in their meta-analysis, theorized and examined the compatibility principle, treating multiple responses to job attitudes as unique behaviors (Table 5).

Paper category, number of papers in the category and concepts related to positive attitude outcomes.

| Category | Number of papers | Concepts related |

|---|---|---|

| In-role behaviors | 9 | Performance |

| 1 | Effectiveness/Productivity | |

| 1 | Mistakes | |

| 1 | Work effort | |

| 1 | Compliance | |

| 1 | Safer patient outcomes | |

| Total | 14 | |

| Extra-role behaviors | 5 | Citizenship behavior |

| 2 | Turnover intention | |

| 1 | Manager's voice behavior | |

| 3 | Employee behavior | |

| 2 | Knowledge-sharing | |

| 1 | IT use | |

| 1 | Less process information | |

| 1 | Proactive behavior | |

| 1 | Civic virtue | |

| Total | 17 | |

Fourteen papers were related to in-role behaviors centering on behaviors that are necessary for the completion of the responsible work (Williams and Anderson, 1991). In general, positive attitudes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment and well-being of employees are predictors of important organizational outcomes such as effectiveness and productivity (West & Dawson, 2012). For example, the research carried out by Edgar, Geare, Zhang, and McAndrew (2015) among knowledge-intensive professionals revealed that well-being improves performance. Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes's (2002) meta-analysis of 8000 business units and 36 companies showed that engagement positively affects performance. Cohen and Liu (2011), following the person–organization fit (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986) in a knowledge-intensive context, confirmed the link between positive attitudes and in-role behaviors among Israeli teachers. In healthcare, Prins et al. (2010), using a sample of 2115 Dutch resident physicians, found that those who were more engaged were less likely to make mistakes. Laschinger and Leiter (2006) in a study of 8597 hospital nurses revealed that higher levels of nurse engagement led to safer patient outcomes, where the JD-R model could be implicitly related. Wright (2014), following the self-determination theory, argued that happiness improves the job performance of R&D professionals, and Bakker and Bal (2010) demonstrated that Dutch teachers’ engagement improved their performance.

Happiness at work can also predict extra-role performance behaviors, which can be defined as those behaviors that support task performance by strengthening and maintaining the social and psychological context (Borman & Motowidlo, 1997). Seventeen papers included extra-role behaviors. There is wide evidence supporting the idea that positive attitudes increase a individual's proactive behavior (behavior that goes beyond their official job description and aim to improve a given job), such as citizenship behavior and knowledge-sharing (Chen & Chiu, 2009; Saks, 2006). Restubog, Bordia, and Tang (2006), in a sample of IT employees, showed that affective commitment increases supervisors’ civic virtue. Alfes, Shantz, et al. (2013) and Alfes, Truss, et al. (2013) highlighted the mediating effect of engagement in the relationship between HRM practices and employee behavior. Ekrot, Rank, and Gemünden (2016), using a sample of project managers and following the self-consistency theory, showed that affective commitment strengthens a project manager's voice behavior. Under the social capital theory, Camelo-Ordaz, Garcia-Cruz, Sousa-Ginel, and Valle-Cabrera (2011) examined a sample of R&D workers and found that affective commitment improves knowledge-sharing and innovation performance. Women social workers in healthcare also seem to improve their citizenship by means of affective commitment (Carmeli, Dutton, & Hardin, 2015). In a multilevel study, Salanova and Schaufeli (2008) evidenced the mediating role of engagement in the relationship between job resources and proactive behavior.

More recently, Salas-Vallina, Alegre, and Fernandez (2017) empirically found that happiness at work fosters organizational citizenship behavior through the mediating role of organizational learning capability. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment are negatively associated with the intention to quit (Meyer et al., 2002). In a study of 139 employees from two software development companies, Chen, Zhang, and Vogel (2011) found that engagement was positively related to knowledge-sharing.

6Conclusions and future research directionsPositive psychology has attracted the attention of researchers (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), although there is still some debate on how helpful happiness at work might be (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017) and what happiness at work depends on (Muchiri et al., 2012). Moreover, different positive attitudinal constructs appear to overlap with happiness at work (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012), which does not help to clarify this concept. To our knowledge, there are no previous reviews of the concept of happiness at work in knowledge-intensive contexts, and our aim is to shed light on this, its antecedents and its consequences, framed in work contexts where knowledge is crucial.

Being happy is fundamental for most people, and especially for employees who intensively use knowledge at work. These workers should be examined in isolation (Meyer, Stanley, & Vandenberg, 2013). Positive attitudes, such as HAW, which create an appropriate atmosphere at work (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017; Salas-Vallina, Alegre, et al., 2017), are essential in contexts in which the process of generating, acquiring, and combining knowledge are necessary (Kogut & Zander, 1992).

First, we have explained the wide range of positive attitudinal concepts, focusing on those that better represent positive attitudes at work namely, job satisfaction, engagement, commitment, hedonia and eudaimonia, well-being, psychological capital and happiness at work, to clarify the different aims and scopes. While all these concepts have been distinctively defined, further research needs to focus on wider positive attitudinal concepts. In general, most attitudinal concepts are too narrow to explain positive attitudes at work, and only the happiness at work concept (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017) attempts to broadly cover the territory of happiness at work.

Second, our study reveals that in knowledge-intensive contexts, happiness at work depends mainly on work context factors, leadership styles, social interactions, and personal resources. Three underlying theories prevailed among these papers: the job demands-resources theory, the social exchange theory and Warr's Vitamin model. The latest research (from 2015 until now) follows the JD-R model and examines the effect of the transformational leadership style and the inspirational leadership style on happiness at work. It seems that those leadership styles which focus on people, such as transformational, authentic and creative leadership, have greater impact on happiness at work, compared to transactional leadership styles (Berson & Linton, 2005). In addition, social interactions and high-quality connections foster knowledge-intensive workers’ happiness at work (Dutton & Ragins, 2007). One might wonder whether knowledge-intensive workers could work under different organizational structures beyond leadership, such as autonomous work and network relationships (Alvesson et al., 2016). Future research should address alternative organizational structures.

In addition, engagement is a key construct that has been analyzed in detail (see the narrative review of Bailey et al., 2017). For example, Van Wingerden, Derks, and Bakker (2017) examined the positive effects of personal resources on engagement. The work context is also a central construct, which includes managerial support, feedback and opportunities for career development, and a fair salary, and it has been related to higher well-being (Vakkayil, Della Torre, & Giangreco, 2017) and increased job satisfaction (Gevrek et al., 2017). Organizational support and justice also predict affective commitment (Sharma & Dhar, 2016). Opportunity for skill use, variety, environmental clarity (Warr, 2007), dignified treatment, fairness, pride in the company and camaraderie with colleagues (Sirota et al., 2005), autonomy (Heijstra & Jónsdóttir, 2011) and flexible working (Golden & Veiga, 2005) also seem to be contextual happiness at work antecedents for knowledge-intensive workers.

In addition, personal resources, such as resilience, have been recently examined as an antecedent of job satisfaction (McVicar, 2016).

Third, past research shows that promoting happiness at work is a worthy goal. The relationship between positive attitudes and performance has been defined as the ‘Holy Grail’ of research in organizational behavior (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). In-depth meta-analyses ratify the influence of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on both in-role and extra-role performance (Harrison et al., 2006; Harter et al., 2002), particularly in complex jobs (Judge et al., 2001). However, more research is required in the positive attitudes-performance relationship. This study concludes that the main outcomes of happiness at work are related to in-role performance behaviors and extra-role performance behaviors. Four main theories predominate in the happiness-outcomes analysis: the social exchange theory, the JD-R theory, the self-determination theory and the positive organizational theory. While some studies argue that positive attitudes positively mediate the HRM-performance, inconclusive findings are shown by others (Conway & Monks, 2009; Snape & Redman, 2010). Stronger consistence in the mediating/moderating role of happiness at work among knowledge-intensive workers is needed. The most recent research has focused on how happiness at work promotes organizational citizenship behaviors among medical specialists (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, et al., 2017), the effects of teachers’ commitment on intention to leave (Morin, Meyer, McInerney, Marsh, & Ganotice, 2015), and the impact of affective commitment on a project manager's voice behavior (Ekrot et al., 2016).

Harrison et al. (2006) developed a robust meta-analysis and concluded that job satisfaction and organizational commitment predict performance,

Fourth, Harrison et al. (2006) and Fisher (2010) suggested that a wider attitudinal measure should be developed to understand work behavior, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment and other related constructs. Our research highlights the need for a broad-based, global measurement of happiness at work, such as Salas-Vallina et al.’s happiness at work construct. This is a general, broad-based attitudinal concept that includes a large number of constructs, ranging from eudaimonic to hedonic attitudes at different levels of analysis. We argue that the concept of happiness at work needs to be understood as an umbrella concept that comprises diversified factors, namely, engagement, job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment (Fisher, 2010; Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017). This construct seems to work accurately in knowledge-intensive contexts (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017; Salas-Vallina, Alegre, et al., 2017), though needs further empirical evidence beyond the health sector.

Fifth, the predictive utility of happiness at work requires a wide attitudinal measure.

This research is focused at individual level, yet positive attitudes literature in general, and the knowledge-intensive research in this field in particular, show a tendency to use multilevel methods of analysis (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008), which might provide further advances for both theory and practice. Following the compatibility principle suggested by Harrison et al. (2006), and empirically checked in a knowledge-intensive context (Salas-Vallina, Alegre, et al., 2017), wider positive attitudinal measures predict better individual behaviors. We suggest moving forward in the conceptualization and measurements of happiness at work, toward a widely checked construct in different economic sectors and countries.

In conclusion, the motivation of knowledge-intensive workers is a highly challenging task for many managers and academics. Accessing and retaining highly skilled knowledge-intensive workers is very competitive, because of the amount of value they add. Jobs where this type of employees can gain autonomy, communication and recognition seem to facilitate employees’ happiness at work. Knowledge-intensive companies need worker commitment, satisfaction and engagement and therefore strategies must be focused on these areas. If the nature of a job is more challenging, with greater opportunities for growth and advancement, knowledge-intensive workers give their best to the organization, no matter how difficult the job is. Employment relationships are changing, the relationship between employers and employees needs to be strengthened, and happiness at work might be the clue for retaining the best employees in the future (Fisher, 2010).

7Implications for practiceDespite the number of studies, there is little evidence about happiness at work that could be maintained with a minimum of certainty. Limited knowledge has been developed about what happiness at work means, how to measure it, or what its antecedents and outcomes are. A first step was taken by Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al. (2017) in measuring and conceptualizing HAW in knowledge-intensive contexts, and revealing the important role of transformational leadership in driving levels of HAW. However, the wide range of attitudinal measures surrounding happiness at work requires further clarification. A selection and clarification of these concepts should be developed, as should the effects of more recent constructs, such as altruistic leadership and individual ambidexterity, on HAW.

We have provided evidence that research in knowledge-intensive contexts is scarce compared to other contexts. In this piece of research, 87 papers were selected from a total of 615, which means that 14.5% of the papers examined belonged to a knowledge-intensive context. Employees in knowledge-intensive contexts are more satisfied at work (Tarcan et al., 2017) and it seems that they should be examined in isolation (Meyer et al., 2013), compared to employees from other contexts. Therefore, we suggest further research framed around employees that intensively need knowledge to perform their job.

Although the JD-R model dominates the evidence base, the background theories are dispersed and fractured. A varied number of meanings are related to HAW, which make it difficult to understand it as a single construct. The emergent research emphasizes the need to conceptualize HAW as a wide construct in relation to individual energy and passion at work (engagement), the evaluation of job characteristics (job satisfaction) and the feelings of belonging to the organization (affective organizational commitment) (Salas-Vallina, López-Cabrales, et al., 2017) under the JD-R model. To suggest further research on the topic in knowledge-intensive contexts for practitioners, it is fundamental to go beyond the JD-R model and examine the antecedents and outcomes of HAW based on the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989). For example, which HRM practices have a positive impact on HAW? How can HAW foster work performance?

An interesting road for research would also be to combine different levels of analysis into a multilevel framework. This perspective could consider individual viewpoints (individual level), the contextual factors required to understanding the setting within which happiness at work is experienced (group/unit level), and the human resource strategies employed (organizational level). Little evidence from multi-level analyses has been found.

8LimitationsDespite the identification and comprehensive review of positive attitudes literature, our narrative review has its limitations which should be acknowledged. First, our review only considered papers published in English. Non-English language contributions were therefore omitted. Another limitation centers on the decision to discard publications that did not follow our criteria, and in consequence, papers based on other positive attitudes such as involvement were omitted. Although this decision is based on quality considerations, it limits the breadth of this research. In addition, we restricted our research to the individual level of analysis. Future research should consider a multi-level approach, in which the effect of general human resource practices on individuals’ happiness or vice versa is examined.

Conflict of interestNone.

This research is part of the Project ECO2015-69704-R funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness and the State Research Agency. Co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).