This paper contributes to a better understanding of the complex phenomenon of institutions and the moderation of the main antecedents of business customer experience. Following a combination of literature review and three fieldworks, the main antecedents of business customer experience have emerged: interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and participation in the co-design of services. The role of institutions (level of formalisation) has also been considered as a possible moderator. Consequently, a conceptual framework has been developed which includes seven research propositions. The first four research propositions are related to the main elements of the model and suggest new relationships among constructs. The other three research propositions are suggested and empirically examined using Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to find causal configurations and to identify pathways that lead to business customer experience. Necessity and sufficiency of conditions that lead to a positive business customer experience are discussed for both scenarios of high and low formalisation of institutions.

Service is understood as the application of resources for the benefit of others (Vargo & Lusch, 2004) and can be regarded as the fundamental unit of exchange (Siltaloppi & Vargo, 2014; Vargo & Lusch, 2017). The conceptualisation of value as co-created by multiple actors requires high levels of coordination and resource integration (Koskela-Huotari & Vargo, 2016; Peters, 2016; Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2008; Vargo & Lusch, 2011). This co-creation of value is coordinated by institutions and institutional arrangements that are considered as collectively developed elements that guide, constrain and coordinate value co-creation within service ecosystems (Vargo & Lusch, 2016). Although there is a consensus about the significance of institutions, there is, however, yet a lack of models for a better understanding of the role of institutions on other key elements of value co-creation. This complexity is understandable due to the nature of institutions that can be comprehended as “invisible structures” (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021), that is, assemblages of enduring norms, rules, assumptions, and beliefs that can be shared by actors of the service ecosystems.

After a methodical review of the literature, we have identified two main gaps: the first one is related to institutions and the second about business customer experience. In relation to the first, this paper seeks to contribute to the theoretical gap that connects the role of institutions in improving actor resourceness in interfunctional coordination management. Koskela-Huotari et al. (2020, p.383) refer to this perspective as “institutions inhabited by actors” and catalogue it as a neglected aspect of institutions in service research as well as a future research area.

There is a consensus about the need for a deeper investigation on the role of institutions, and to develop mid-range theories and frameworks that can help academics and service practitioners to improve the understanding of its strategic role in relation to customer experience enhancement, as “numerous institutional arrangements work simultaneously as sense-making frames for actors in the process of potential resources gaining their “resourceness”” (Koskela-Huotari & Vargo, 2016, p. 174). The role of institutions as a resource context (Caridá et al., 2022; Koskela-Huotari & Siltaloppi, 2020) plays a critical role in defining shortcuts, rules, standards, language, meanings and many similar phenomena that influence relationships, behaviours and business practices, consciously or unconsciously, and determines the degree of resource integration among actors. Therefore, it is relevant to examine how institutions can contribute to develop coordinated behaviours with special attention to the level of formalisation of institutions, as highlighted by recent literature (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020; Bocconelli et al., 2020; Peters, 2016).

The second important gap is framed in the context: the lack of conceptual frameworks about business customer experience (BCX) and specifically with the perspective of institutions has been highlighted in recent literature (McColl-Kennedy et al., 2019). Scholars agree that CX can be considered a key driver of behaviours in the B2B context (Kuppelwiesser et al., 2021) and, therefore, more insights are needed in B2B settings to provide a better service experience (De Jong et al., 2021). It is noteworthy to highlight that there is not a clear conceptualisation of the role of institutions on customer experience that manifest unexplored connections between constructs (Jaakkola, 2020). In this sense, Becker & Jaakkola (2020, p. 642) posit the third premise of customer experience characterising CX as “subjective and context-specific” and propose institutions and institutional arrangements and its impact on CX as a potential new research topic.

In this perspective, the ‘actor-to-actor’ (A2A) view (Caridá et al., 2022; Polese et al., 2017; Vargo, 2009) arises to avoid the simplistic perspective of considering value creation just as a linear process in which hypothetically value is created only in a unidirectional (summative) flow from service provider to consumer. The reality is more complex than such assumption, and the ecosystem perspective of Service Dominant (S-D) logic can offer a more appropriate perspective to shed light on the role of institutions as a moderating factor on CX configuration, capable to connect resources in a integrative way (Bocconelli et al., 2020, Peters, 2016; Peters et al., 2014), in which results exceed the sum of resources of all the actors in the system Consequently, still more sophisticated research is needed on the development of midrange theoretical frameworks that can guide and support additional empirical investigations with further managerial contributions (Brodie & Peters, 2020) that can also bridge the theory-practice gap (Gummesson, 2017; Nenonen et al., 2017).

According to the four-type classification of conceptual articles, this current research could be considered as a model (Jaakkola, 2020), as we aim to develop a theoretical framework that represents relations between constructs. The framework will be developed integrating findings and insights from our fieldworks and obviously in combination with critical discussion of the relevant literature which allows an open dialogue between theory and practice.

Consequently, to achieve these two aims, the following research questions will be addressed:

RQ1: What are the main antecedents of business customer experience and their relationships?

RQ2: How can institutions moderate the relationships between the antecedents and business customer experience?

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies investigating antecedents of BCX using fsQCA. All previous investigations were conducted with linear approaches but none using causal configurations (non-linear), which would justify the following research questions:

RQ3: Are there any necessary and sufficient conditions or casual configurations and which specific pathways can enhance business customer experience?

RQ4: How will practitioners adopt the identified pathways?

In this regard, the aim of the present work is to develop a conceptual framework capable to give a theoretical and empirical support to the connections between interfunctional coordination (IC), service co-design (SD), and business customer experience (BCX). This will be done with analytical rigour (Jaakkola, 2020). Adopting the S-D logic approach, our contribution is framed on foundational premise and axiom: FP11/A5 of service dominant logic: Value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements (Vargo & Lusch, 2016), giving institutions a moderator role in these relationships, capable to influence BCX with the appropriate institutions and institutional arrangements that make possible the service co-design through interfuctional coordination and a high level of actor engagement. The second aim is to disentangle the complexity that can describe different pathways to enhance customer experience and give answer to the demand for research that calls for the identification of subjective and context-specific factors that determines CX. This contribution is framed on premise 3 of CX, that highlights the context-specific character of CX (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020, p.640).

The remainder of the article is organised as follows: in the second section we describe in-depth the context of the research and the application of Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. In Section 3, the theoretical approach to institutions and customer experience are developed in connection with interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and service co-design. Sections 4 and 5 go through the research propositions. Finally, Sections 6 and 7 conclude with the discussion of the study with theoretical and managerial contributions, limitations and suggest strategies for future research.

2Institutions and customer experience2.1InstitutionsThe role of institutions has grown and increased in the last years, fostered by the ever-evolving business models that, in an open economy context, need to be in a continuous process of change. The rules that connect actors in this context can facilitate engaged actors to improve resource density though value co-creation, making cross-functional coordination a keystone to connect actors and resources (Akaka et al., 2013), resulting in an improved service co-design that accounts with the collaboration of all the actors in the organisation (Chandler & Vargo, 2011; Patrício et al., 2019; Storbacka et al., 2016).

From the S-D logic perspective, institutions represent the context for interaction in service ecosystems (Brodie et al., 2019). Vargo and Lusch (2016, p.11) emphasise the role of institutional arrangements as “keys to understanding humans’ systems and social activity such as value co-creation”. The current research contributes to the Fundamental Premise 11/Axiom 5 of S-D logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2017 p.47): “value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements”. Husmann, Kleinaltenkamp, and Hanmer-Lloyd highlight the role of actors exchanging resources in service system and posit “Resource integration is thus the key mechanism to co-create value” (2019, p. 1582). The consideration of institutions as a resource context can help to facilitate the potential resources to arise and improve the resource density in the ecosystem (Fehrer et al., 2020; Koskela-Huotari & Vargo, 2016; Wieland et al., 2016). Still, this terrain is a recent area of research and there are very limited contributions regarding the role of actors as facilitators to improve resource integration through value co-creation (Koskela-Huotari & Siltaloppi, 2020; Mele et al., 2018; Nenonen & Storbacka, 2018). In this perspective, Koskela-Huotari et al. (2020, p.31) propose “Institutional arrangements act as sense-making frames for determining the “resourceness” of potential resources”. We adopt this perspective and consider institutions (formal and informal) as the sense-making frame to connect resources in an ecosystem. Regarding institution´s formalization, Zhao et al. (2021, p. 16), conceptualise it as “the extent to which the focal firm/partner dyad is coordinated and controlled by detailed contractual terms” and Barry et al. (2021) consider the moderating effect of institutional formalisation on commercial communication and exchange. Following the organisational perspective of institutions, Ostrom (2005, p. 3) conceives institutions as “the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structure interactions including those within families, markets, firms and governments”. Scott (2014) identifies three institutional pillars: (1) regulative institutions, manifested by the existence of rules, laws, sanctions that constrain and regulative behaviour; (2) normative institutions that define what is appropriate, what the goals are, and the way to achieve them, and (3) cultural or cognitive institutions, referring to culturally supported practices that are taken for granted. More recently, Jaakkola et al. (2019, p. 499) note that “it is fruitful to examine how diverse actors with differing institutional logics achieve directions for joint actions, and key obstacles therein” and Edvardsson et al. (2021, p. 296) place the emphasis on the need to understand institutional connections among actors in an ecosystem. In this sense they posit: “institutional logic matter as they ultimately enforce and shape actor´s behaviours”.

The present research puts the focus on the level of formalisation of institutions and its capability to connect actors in B2B context to facilitate resource integration that makes possible service design to be the result of a collaborative action (service co-design) and involving the whole organisation to develop this systemic approach (cross-functional coordination).

2.2Customer experienceFollowing the S-D logic ecosystem approach, and the role of value-in context in the strategy to co-create value, Becker & Jaakkola (2020, p.640) propose as the third premise of customer experience that “customer experience is subjective and context-specific” and highlights the need for research in this specific perspective that we develop in the present paper (p.641): “Future research could look beyond customer experience research to identify potentially relevant contingencies for customer experience formation”. This perspective connects with, FP10 of S-D logic: “value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary” (Vargo & Lusch, 2017, p. 47). Following that premise as the customer is a key beneficiary, the evaluation of service experience becomes a critical challenge. Therefore, customer experience has to be framed in a context in which value is co-created by the actors and institutions (formal and informal) moderate the capability of the environment (cross-functional coordination) to facilitate service co-design though engaged actor´s co-creation.

In this perspective, Ostrom et al. (2021) also identified that customer experience (CX) has become a dominant marketing concept. In their recent study, they show that over 90% of business leaders believe that delivering a relevant and reliable CX is critical to business performance. Holbrook & Hirschman (1982) suggest that the experiential dimension is crucial to understand consumer behaviour. Customers are rational and emotional animals (Schmitt, 1999) and experiences provide sensory, emotional, cognitive behavioural and relational values which makes the understanding of the phenomenon extremely complex. This complexity, which is intrinsic to the nature of any experience, represents a special challenge when it comes to disentangle the comprehension of the evaluation of service experiences (Jaakkola et al., 2015).

De Jong et al. (2021) recently identified five important trends shaping B2B services. The second theme was the personalisation of service experiences being one of the main challenges that can be addressed in multiple forms, but an efficient way is the co-design of service experience.

In that sense, according to FP10: “value is always uniquely and phenomenologically determined by the beneficiary” (Vargo & Lusch, 2017, pp. 47). Following that premise as the customer is a key beneficiary, the evaluation of service experience becomes a critical challenge. Therefore, customer experience should never be overlooked when understanding the dynamics of value co-creation.

3Research design and methodology3.1ContextThe present investigation addresses these research questions adopting an S-D logic approach trying to provide answers that focus on the customer experience in a specific context. Chandler & Vargo (2011) were pioneers to propose the need to introduce contextualisation and value-in-context to shed light on how resource integration takes place because idiosyncratic situations in which resources are brought together need to be considered and the way their uses and limitations are understood. This will affect their “value” in those interactions (Quero et al., 2017; Siltaloppi & Vargo, 2014). Regarding the context, we have incorporated other actors rather than just the “focal actors”, such as service providers and service beneficiaries (Vargo & Lusch, 2011) because the network of resource-providing actors can support comprehensive analysis of the service ecosystem. This gains prominence for a better understanding of the role of institutions and institutional arrangements. For that purpose, pharmaceutical distribution is the chosen sector as it is under severe reconfiguration (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2019) and can constitute a clear case of service system transformation (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021). Another relevant characteristic of this sector is that it allows researchers to avoid the traditional dyadic interaction customer-service provider for the design of services as it is part of the healthcare ecosystem where there are many interdependencies between actors and system levels (Patrício et al., 2020), being considered an ecosystem (Sahasranamam et al., 2019) and an example of service system transformation (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021). Therefore, the identification of focal actors has been conducted with the perspective of the application of the variables under investigation: interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and service co-design. In fact, there are other actors interplaying in this ecosystem such as pharmaceutical laboratories, suppliers of laboratories, national and regional governments, professional bodies, regulatory institutions, healthcare providers, private distributors, pharmacy stores and direct service providers of pharmacy stores. Thus, for a better fit with the purpose of this current research pharmaceutical distributors were selected as key actors due to their demonstrated predominant and active role in co-creation of value with other actors of the ecosystem (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2019).

The research was developed in a region of Spain (Andalucía), with more than 8 million inhabitants and a health system with a big scope that resulted appropriate to frame the empirical approach.

3.2MethodsAll these previous considerations lead us to carefully develop a solid strategy for the research design, which is always important, but mainly for conceptual articles as they must be grounded in a clear research design (Jaakkola, 2020). Table 1 (See in Appendix) illustrates the overall research design of this paper.

We have used an iterative process from theory to data, and vice versa, with an abductive approach. In fact, our proposed model was improved five times based on the empirical findings that were emerging during our discussions considering the literature (Dubois & Gadde, 2002, 2014; Reichertz, 2004) obtained from three fieldworks; Studies 1, 2 and 3.

3.2.1Study 1. online focus group-1Study 1 consisted of an online focus group following methodology developed by Stewart & Shamdasani (2017). Before conducting this focus group, we reviewed the relevant literature about the antecedents of BCX. There is limited research about customer experience in business contexts; however, some antecedents of customer experience have been found. In that sense, Kim et al. (2013) investigated user engagement. Customisation has been identified as a critical antecedent for customer experience (Chang, Yuan, & Hsu, 2010) and this requires interfunctional coordination (Auh & Menguc, 2005; Ruiz-Alba et al., 2019). Service offering and the design of services are also considered as antecedents of customer experience (Kamaladevi, 2010) connecting with co-designing of services .

Collection of data from expert sources is facilitated by this method in better conditions than other alternatives which make it more difficult to meet face-to-face. In this case anonymity was not required; therefore, it was designed with a synchronous approach where all participants could interact. The profile of participants selected were six in total: two of them were business customers; two were service providers and the other two business consultants. The tool used was video conference using Microsoft Teams solution. The session lasted 75 min and was moderated by one of the researchers of this paper. The objective of Study 1 as indicated in Table 1 was the identification of main antecedents of BCX. Data collected were stored as Data set 1 and thematic analysis was conducted using NVivo 12. The main results will be presented in the relevant section, but we can anticipate that the main antecedents of BCX were identified as: interfunctional coordination, customer engagement, participation in the service co-design and institutions (level of formalisation) that was suggested to be more as a moderator rather than just an antecedent.

3.2.2Study 2. InterviewsStudy 2 consisted of in-depth interviews. Qualitative methodology was appropriate (Yin, 2014) due to the nature of the main objective that was to identify themes, relationships between antecedents of BCX, develop matrices and ultimately to facilitate data that could contribute to the development of a conceptual framework in discussion with relevant literature. Sample was selected with the intention to cover different segments of business customers (Flick, 2010). In total, 25 participants were interviewed, all of them being business customers. The interview protocol was developed based on the main findings from Study 1: the three mentioned antecedents and a possible moderator. Data collected constituted Data set 2 and was analysed using NVivo 12.

3.2.3Study 3. online focus group-2We invited five participants. All of them were business customers of pharmaceutical distributors and none of them had participated either in the online focus Group-1 or in the in-depth interviews. We used Google Groups (asynchronous). Before participating we explained to each one of them the conditions (interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and participation in service co-design) and the outcome of BCX. For the evaluation of the pathways, we focused only on those found in the scenario of high level of institutional formalisation and we explained them the meaning of these two pathways. Once they joined the online focus group, they had to rate each pathway based on the following criteria: a) complexity of implementation, b) economic cost of implementation for the firm; d) predisposition to each solution; e) positive impact on customer experience.

4Research propositions and conceptual frameworkThe most relevant results from Studies 1 and 2 will be presented in this section in critical dialogue with relevant literature. We present those results that are pertinent to the development of the research propositions and consequently of the proposed conceptual framework.

4.1Interfunctional coordination and customer experienceIn addition to the analysis of the unexplored connection between constructs, we introduce a new construct (Jaakkola, 2020) in this framework: interfunctional coordination, which will contribute to the systematic nature of value which is co-created by multiple actors connected through the exchange, integration, and application of resources (Lusch & Vargo, 2014).

A recent article published in the Journal of Marketing has identified the 10 most relevant academic articles on marketing journals. The top one from that list is "Marketing Organization: An Integrative Framework of Dimensions and Determinants" published also in the Journal of Marketing in 1991. It is interesting to mention that this paper begins with this sentence: “Over the past few years, there has been growing interest in marketing's cross-functional relationships with other departments…” (Workman et al., 1998 p.21) and they clearly focused their study “on the non-structural dimensions of cross- functional dispersion of marketing activities, the power of marketing, and cross-functional interaction” (p.27). It gives us an idea about how interfunctional coordination is at the heart of the marketing discipline.

Interfunctional coordination allows actors to leverage all available resources across departmental boundaries to create superior customer value (Narver & Slater, 1990).

All actors co-create value through resource integration and service exchange (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). Due to the collaborative nature of value creation (Vargo & Lusch, 2011) it is expected that interfunctional coordination can play an important role at firm level in resource integration and value co-creation in a combination of resources integrated (Vargo & Lusch, 2011). For that reason, the activities of the different actors involved in value co-creation is not something that happens spontaneously, but conversely, needs to be coordinated.

Coordination is essential but it can generate conflicts. In that sense, negotiation is at the heart of interfunctional coordination as it can resolve the tension between actors when dealing with limited resources. According to the resource integration framework (Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2012) the role of integrating resources is critical. Kleinaltenkamp et al. (2012) identify as integrating resources: process(es); cooperation and collaboration. These authors suggest that effectuation theory (Read et al., 2009) can help to explore how collaboration occurs through commitments between networked actors. Following that line of argumentation, we understand that interfunctional coordination could be included within the category of integrating resources, as is responsible for providing a context that improves actor engagement (Storbacka, 2019), actor disposition and resource density. Storbacka et al. (2016, p. 3012) propose actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation and propose the concept “actor disposition” to bridge the process from theory to practice: “actor disposition is defined as a capacity of an actor to appropriate, reproduce or, potentially innovate upon connections in the current time and place in response to a specific past and/or toward a specific future”. In this perspective, interfunctional coordination improves both actor disposition and resource density, making possible the collaborative connection among actors in the ecosystem.

Information and knowledge kept in functional silos does not make a positive contribution to firm's performance (Javalgi et al., 2014). Most of the participants manifested that they have observed clear cases of lack of coordination. One participant said: “The greatest lack of coordination happens mainly between sales and operation with negative impact on our experience as customers”. In similar vein, another participant said: “I am not concerned about the lack of coordination that is visible. I guess that the invisible lack of coordination is more detrimental for us. In particular, I think that in our providers, the departments of marketing and finance don´t get along well. But I have no evidence to prove it”.

Customer demands require that all functions of a firm become more involved in the customer relationship (Flint & Mentzer, 2000). Moreover, one of the benefits of a good level of interfunctional coordination (Inglis, 2008) is that it increases the speed and quality of communications between departments, which can enhance resource integration.

Related to speed, one participant manifested: “My experience when the solutions take longer than expected is that the main excuse they give is related to latent conflicts between their departments. They don´t clearly tell you but it is implicit in the way they tell you”.

One important aspect of interfunctional coordination is the role of institutional processes and collaborative processes that are clearly orientated to secure interfunctional coordination within firms for an efficient resource integration (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2019). In that sense Frow & Payne (2011) found five processes for resource integration, one of them being knowledge sharing (third process) that is facilitated by the interfunctional coordination and can clearly contribute to “value alignment”, which will consequently enable all actors to offer value propositions efficiently (Siltaloppi & Vargo, 2014).

Value is always co-created (FP6) and this value co-creation is made possible by resource integration (Peters, 2016; Storbacka et al. 2016; Vargo & Lusch, 2011) and resource integration needs to be coordinated. Therefore, interfunctional coordination can be regarded as an important element for value co-creation. In this sense Rather et al. (2022, p.560) propose the need for introducing the employee´s perspective when analysing CE, CX and co-creation, given its “interactive nature”. A positive customer experience is a tangible expression of the value for the customer and ultimately for the firm because what is beneficial for the customer, in most cases, should be also beneficial for the service provider. Therefore, customer experience as a form of value co-creation, needs to be coordinated. Accordingly, this leads to the first proposition:

Research Proposition 1: Interfunctional coordination has a positive influence on business customer experience.

4.2Customer engagement and customer experienceCustomer engagement is theoretically rooted in two interrelated research streams: relationship marketing (Gummesson, 2008; Harmeling, 2017; Kumar et al., 2010) and S-D Logic (Chandler & Lusch, 2015; Vargo & Lusch, 2017), resulting in an active conceptualisation of the customer, that co-creates value through connections to other actors in business markets. The value of engaging customers in co-creation activities amongst service ecosystems is a growing field that demands for research to improve knowledge in this context (Peltier et al., 2020; Rather et al., 2022). The role of actors in general and business customers’ engagement (BCE) demands a specific analysis and research (Ekman et al., 2021). SDL (Vargo & Lusch, 2017, p.47) posits in its fundamental premise number nine (FP9) that “all social and economic actors are resource integrators” and FP 6 refers to how resources become value for the actors involved in the transaction by setting that “value is co-created by multiple actors”.

“The level of personal interactions has been decreasing during the last three years. They commercial representatives used to visit me, but I have experienced that since the last few years they tend to communicate with me via WhatsApp”.

Another manifested: “I feel quite disengaged. The relationship with them has turned to be rather impersonal”.

Regarding this process of value co-creation, Brodie et al. (2019, p. 2) define actor engagement as “a dynamic and iterative process that reflects actor dispositions to invest resources in their interactions with other connected actors in a service ecosystem”. These connections have a positive influence on customer experience, and literature increasingly demands “to explore how extant marketing constructs like customer engagement (…) relate to customer experience and interact with each other, resulting in the overall CX” (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016, p.85). In that sense, Brodie et al. (2011) were pioneers in building on relationship marketing and SDL to distinguish CE from other relational concepts and formulate the fundamental propositions defining the conceptual domain of CE. In our research it is of special relevance regarding the FP 1 which posits: “CE reflects a psychological state, which occurs by virtue of interactive customer experiences with a focal agent/object within specific service relationships” (p. 258). The emotional dimension is also critical. One participant said: “My emotional bonds with the provider are barrier to swift to other providers. As simple as that. It is not rational, I know, but it is the way it is”. Building on this FP, Chandler & Lush (2015, p. 9) assert “engagement is based on both: the connections of an actor and the psychological dispositions of an actor” making an interesting distinction between two properties of engagement: internal (i.e. dispositions) and external (i.e. connections). In this same sense, Bolton et al. (2014) put the focus on customer engagement behaviours as a driver to improve service experience, highlighting it represents a strategy for organisations to incorporate customer participation into the joint creation of value.

“My attitude has changed from being enthusiastic and collaborative to a more passive a reactive disposition. I can assure that this is not my fault”.

Adopting this perspective, we consider that customer engagement manifests through behaviours, whereby market actors influence each other´s dispositions and behaviours (Alexander et al., 2018; Fehrer et al., 2020). In the B2B context, there is an explicit demand for research on the connection between customer engagement and service experience. Ostrom et al. (2021, p. 335) frame the research proposition priority in “Technology and the customer experience” under the topic “Critical importance of connections, evolving actor roles and context in the customer experience”. Ekman et al. (2021, p. 186) combine a theoretical and empirical approach to analyse BAE and conclude that “the second manifestation of BAE disposition is experience”. In their research, framed in a B2B context, actor engagement disposition presents two attributes: strategic fit (which is primarily behavioural) and experience (which is mainly emotional). In this line, Kharouf et al. (2020) use the online events context to connect actor engagement with customer experience using structural equations analysis to support the connection with empirical evidence.

The connection between CE and CX has a recent theoretical development and empirical approaches to shed light on this relationship is highlighted in recent literature (Ng et al., 2020; Ostrom et al., 2021). Regarding this connection, Alvarez-Millan et al. (2018) view CE from a managerial perspective, where CE is initiated by the firm and CX is proactively managed. This represents a customer engagement management perspective (CEM) in which customers are seen to have resources that can contribute to the firm's marketing functions (Hollebeek et al., 2019; Jaakkola & Alexander, 2014). Therefore, we formulate:

Research Proposition 2: Customer engagement has a positive influence on business customer experience.

4.3Participation in the service design and customer experienceGiving customers what they want (at a profit) is perhaps the most basic principle of marketing (Simonson, 2005), but to offer them what they want or need, service providers should develop firstly their ability to acquire, internalise, and deploy knowledge effectively as a crucial element to the success of the firm (Grant, 1996). For that reason, companies should not neglect to acquire knowledge from their business customers for the design of new services, which can be considered a type of absorptive capacity through the acquisition and assimilation of knowledge (Zhara & George, 2002). Service design is increasingly viewed as an intentional pathway to service system transformation (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021). A critical aspect in services is co-design by service providers and customers (Kristensson et al., 2008). Chae (2012) proposed three dimensions to understand service co-design: supply-side, customer-side, and geographical/institutional. This current research will consider these three dimensions.

The incorporation of customer knowledge will facilitate understanding individual customer preferences and, consequently, to respond to designing tailored offers which has been a routine in many services (Simonson, 2005) but not always. Thus, customised offerings may provide superior customer value but, in many cases, customers may not have well-defined preferences. Furthermore, they can have just a fuzzy view about what they want or prefer but possibly they are not totally sure about what level of service is more convenient for them. Here is when they might realise that they need support and advice from the service provider. This can happen is they invite business customers to participate in the design of a service (co-design). But surprisingly, we found in our fieldwork that 70% of business customers showed a low participation in service co-design of core services. To illustrate how they perceive the impact of this low level of co-design, here is a statement from one of the business customers: “I am sorry to say that our knowledge and experience is wasted: they are losing business as they don´t count on us. They don´t listen to us”.

Personalisation of the service is a key element to enhance customer experience (De Jong et al., 2021). In that sense, Jaakkola & Tehro (2021) developed a new scale to measure service journey quality (SJQ) and the first dimension was journey personalisation. One of the items of that scale was “X's service process is designed to consider my specific situation”. In our Study 2, we found that 30% of business customers had a high level of participation in the co-design of services. One of the participants manifested: “I am one of the chosen customers that has joined what they name as active customers. This means a commitment from both parties to get involved any time they decide to launch a new service. My experience since I joined the scheme is that the specific needs of my business are really take into consideration when a new service is designed. It does not mean that they will implement 100% our suggestions or initiatives, but the fact that we are involved has changed completely our loyalty to our service provider”.

In addition, previous studies reveal the importance of customer participation in the service co-design (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2021). In that sense, Ruiz-Alba et al. (2019) found that, when the level of participation of business customers in the design of services is high, then there are significant effects of servitisation on firm performance. These authors showed that there is a positive impact of advanced services on firm financial and market performance through the mediating effect of servitisation when the degree of customer participation in the co-design of services is high.

The notion that services beneficiaries should play some role in the integrative value-creation process (Vargo & Lusch, 2011) is assumed by most researchers, but this might not always be the case in real business practice; in that sense it is surprising how many service providers have been flying blind without involving their business customers in the co-design of services (Ruiz-Alba et al., 2019). To enhance customer experience, active participation of actors in service co-design has developed multilevel approaches from designing dyadic touchpoints, to customer journeys across service systems (Patrício et al., 2018). As such, one of the participants suggested some conditions to enhance BCX: “The mere fact of designing services together doesn´t guarantee success, I have also told my providers that the experience has to be at the core of service co-design and that if not all the relevant stakeholders are involved, then it will not work at all”.

Therefore, Research Proposition 3: Customer participation in the service design has a positive influence on business customer experience.

4.4Moderating role of institutionsInstitutions considered as rules, norms, and beliefs that enable and constrain action (Scott, 2008) can explain how ecosystems are structured and governed. Institutions can be considered the rules of the game (North, 1990). Most behavioural patterns are guided by the rules of engagement (Jacobides et al., 2018; Kleinaltenkamp et al., 2019) and the level of control within an ecosystem has clear implications for all actors. It can be said that institutions represent the “glue that enables and constrains value co-creation within these social systems” (Wieland et al., 2016, p. 221) and determine how resources are integrated in service ecosystems (Vargo & Akaka, 2012). Formalisation of processes and rules is important but can bring negative side effects. One business customer said: “In the last two years, our service providers are trying to formalise and standardise almost everything and this is backfiring them. They are becoming so impersonal that we are losing sense of proximity and emotional engagement”.

Although the definition of institutions is widely accepted at least with some consensus about the main elements, it can be rather challenging to specify the concept and to make it more tangible and illustrated with examples of non-abstract concepts. As such, one of the business customers expressed: “It is quite shocking to see the lack of clarity about processes and standards from our service providers. Sometimes they seem amateurs. This is specially surprising as we are in a sector that is very much regulated (pharma) with many legal restrictions, our clients need a prescription; the price is also regulated, etc., but our providers are improvising and working with rules of the game outdated”.

Akaka & Vargo (2015) manifested the importance of socio-historic contexts of value creation and the influence of institutions on experience and offered a broader service-ecosystems approach that has been defined as “relatively self-contained, self-adjusting system[s] of resource-integrating actors connected by shared institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchange” (Lusch & Vargo, 2014, p. 161).

One of the findings from our Study 2 was the trend to highlight compliance. “Audit of processes and compliance initiatives are gaining momentum in our service providers, but my view is that it is just fashionable and a pure cosmetic matter that is not adding value to us as customers”.

Some practices diffuse unchanged across firms from promoters to relative passive adopters (Ansari et al., 2010). And it is important to understand the role of communication to avoid that vagueness. One of the participants said: “Policies are mainly found randomly (exist but not properly communicated)”.

Institutions are subject to reconfiguration and rethinking taken-for-granted norms and beliefs, and this is related to service co-design (Kostela-Huotari et al., 2021) and this reconfiguration happens in a context of coopetition. One participant expressed: “Most of our business beliefs are shaped by interaction with our competitors rather than with providers”.

The role of institutions is critical in value propositions, providing both rules and resources for value co-creation (Siltaloppi & Vargo, 2014). In that sense, we found that, although new generations of family members were taking the reins of the business, old assumptions were still constraining their decisions. Illustrating these assumptions one participant manifested: “the influence of first generation is very strong. It is like Hamlet's father: Hamlet's Ghost father King Hamlet from the other life was giving instructions to his son Prince Hamlet. I know many cases on which they are still loyal to the pharmaceutical cooperative that their parents co-founded and they will not swift to other providers for respect to their ancestors”.

Consequently, we suggest:

Research Proposition 4: The level of formalisation of institutions can moderate the relationships between interfunctional coordination, customer engagement, service design and business customer experience.

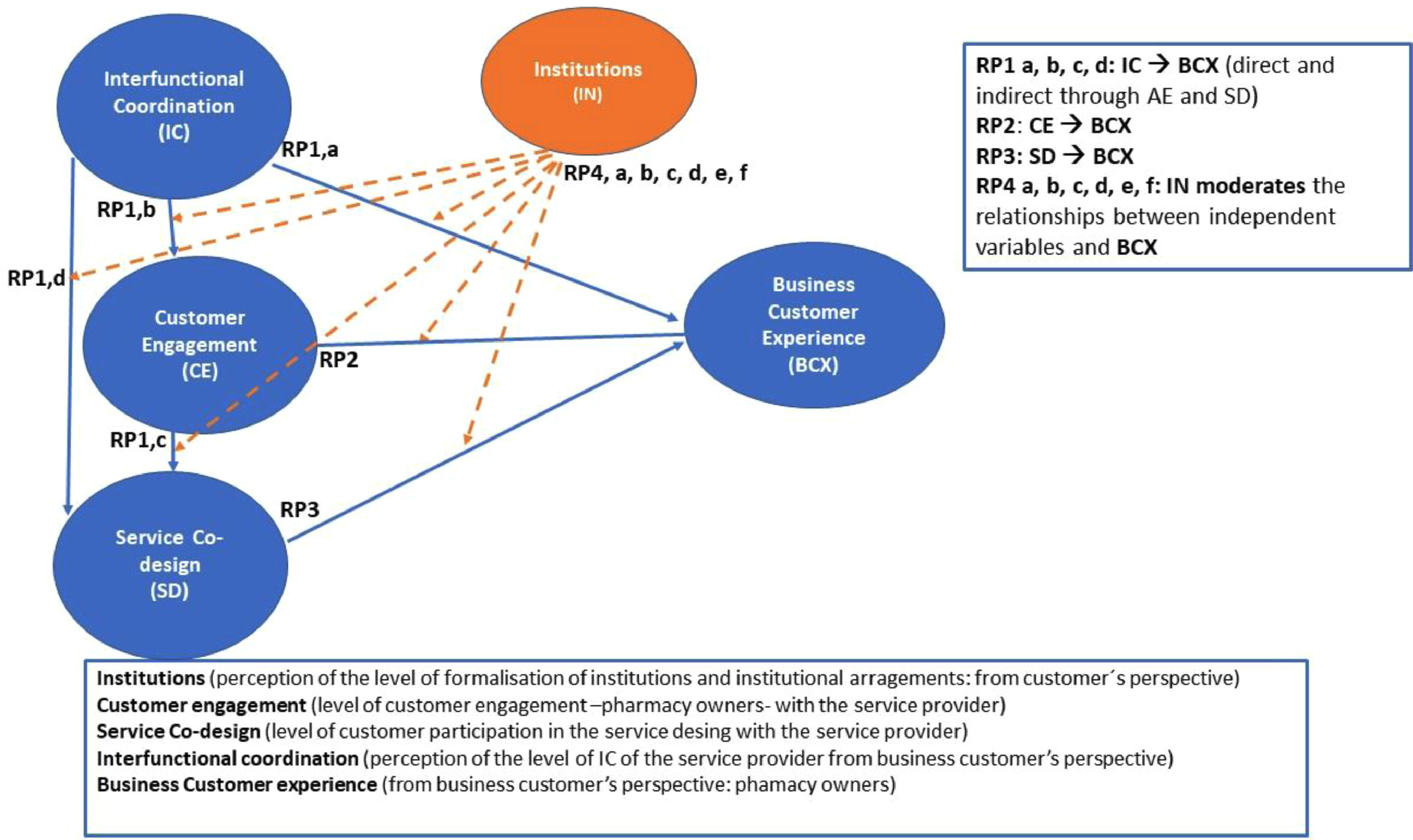

4.5Conceptual frameworkBased on the previous research propositions (RP1, RP2, RP3 and RP4), in this section we present in Fig. 1 a conceptual framework that shows the antecedents of BCX and the moderating role of institutions in the theoretical context of SD-logic.

The three antecedents, interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and participation in the service co-design, should have a direct impact on the outcome business customer experience. Institutions (the level of formalisation) can moderate the five relationships shown in the model (See Fig. 1). Customer engagement and participation in the service design mediate the relationship between interfunctional coordination and customer experience. Thus, this model is designed to be tested in future studies collecting quantitative data via survey for a further analysis using structural equation models. But, as indicated before, for the purpose of this research, this model tries to understand and represent the underlying relationships and to propose the use of this model to be empirically assessed in future studies.

4.6Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): additional research propositions and analysisOnce the conceptual framework has been developed, we will use fsQCA. We seek to find if there are any necessary conditions, and, regarding the sufficient conditions, which are these conditions and/or causal configurations and subsequently to identify the main pathways that lead to customer experience.

Therefore, a question that arises is under which conditions business customer experience can be enhanced. Therefore, three new research propositions are suggested:

Research Proposition 5: Neither interfunctional coordination, customer engagement, nor participation in the service co-design alone are necessary conditions to create a positive business customer experience (BCX).

Research Proposition 6: Sufficient conditions and causal configurations of the antecedents of BCX lead to positive BCX.

Research Proposition 7: Causal conditions and causal configurations that lead to BCX will be moderated by the level of formalisation of institutions.

5Results and discussion from fsQCA analysis5.1Data calibrationAs we explained in a previous section, the data for this analysis were collected in Study 2 via interviews. For the calibration of qualitative data, we followed the six steps developed by Basurto & Speer (2012).

The first procedure in fsQCA requires transforming the original measures into fuzzy-set scores, the input data for fsQCA. Fuzzy-set scores range from 0 to 1 and reflect the degree of membership in the target set. Thus, the three causal conditions (IC: interfunctional coordination, CEG: customer engagement and SD: service co-design) and the outcome (BCX: business customer experience) should be calibrated, and fuzzy scores created.

Fuzzy-set calibration needs the specification of three breakpoints or anchor points, which define the level of membership in the fuzzy-set for each case. Following Ragin's (2008) recommendation, we use fuzzy values of 0.95 for full membership, 0.50 for the crossover point or point of maximum ambiguity, and 0.05 for the full non-membership. To assign which values in our data set correspond to the three anchor points, we fixed the calibration measures on the end points and mid-point following Wu et al.’s (2014) recommendation.

Once all variables were calibrated, we proceeded to identify which causal conditions were necessary and sufficient for business customer experience. But, before performing this analysis, we used the variable Formalisation Institutions (FI) as a moderating variable. To test the moderating role of this variable, we divided the sample (25 cases) into two subsamples. Subsample 1 included 13 cases with low level of formalisation, and subsample 2 consisted of 12 cases with high level of formalisation.

5.2Necessity of the conditionsA condition is necessary if the condition is present every time the outcome is present, i.e., the condition must be present for an outcome to occur. Empirically, a condition is necessary when its consistency and coverage values are above the 0.90 and 0.50 thresholds, respectively (Ragin, 2008).

Table 2 displays the results of the analysis of necessary conditions for each subsample. The results indicate that the consistency of the conditions was below 0.90 in all cases. Thus, none of the conditions were considered necessary to lead BCX in any of the subsamples (i.e., independently of the level of formalisation of the institution).

Analysis of necessary conditions.

Outcome variable: BCX

Source: Own compilation

A condition is considered sufficient if the outcome is present each time the condition is present. Sufficient conditions analysis includes three steps (Schneider & Wagemann, 2010): create a truth table, simplify the truth table, and obtain the final solution.

First, fsQCA applies Boolean algebra rules to build a truth table which includes the membership scores for all the possible configurations of causal conditions (Ragin, 2008). In our case, the truth table for both subsamples, contains eight rows (= 2k, where k corresponds to the number of causal conditions considered for the analysis).

Second, to simplify the truth table, we selected the configurations of conditions that were relevant and consistent with the outcome (customer experience) based on frequency and consistency criteria. In this study, we set the cut-off points for frequency at 2 and the minimum consistency threshold was set at 0.80 for both subsamples (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008).

Finally, fsQCA evaluates which configurations of causal conditions (pathways) constantly lead to high levels of the outcome of interest, i.e., sufficient conditions. FsQCA software provides three solutions: complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions. Following Ragin's (2008) recommendation, we report the last one that is the most interpretable. Thus, Tables 3 and 4 display the intermediate solution for the analysis of sufficient conditions for low and high formalisation of institutions subsamples, respectively.

Sufficient configurations of conditions for BCX (Subsample 1: Low Formalisation of Institutions).

| The configurations leading BCX | Raw coverage | Unique coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC * CEG * SD | 0.538 | 0.538 | 0.876 |

| Solution coverage: 0.538 | |||

| Solution consistency: 0.876 |

Note: IC = interfunctional coordination; CEG = engagement; SD = service co-design ∼ = absence of the condition.

Source: Own compilation

Sufficient configurations of conditions for BCX (Subsample 2: High Formalisation of Institutions).

| The configurations leading BCX | Raw coverage | Unique coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC * CEG * SD | 0.486 | 0.288 | 1.000 |

| IC * ∼CEG * ∼SD | 0.341 | 0.143 | 1.000 |

| Solution coverage: 0.629 | |||

| Solution consistency: 1.000 |

Note: IC = interfunctional coordination; CEG = customer engagement; SD = service co-design ∼ = absence of the condition.

Observing the results, we can see how, in subsample 1 (Low level of formalisation of institutions), there is a unique pathway to reach BCX. However, in subsample 2 (High level of formalisation of institutions) there are two ways to lead BCX. This means that, when the level of formalisation of institutions is high, there is no single way to achieve BCX confirming equifinality (Fiss, 2011).

5.3.1Sufficient conditions for subsample 1: low level of formalisation of institutionsThe solution's overall consistency (= 0.876) and coverage (0.538) presented in Table 3 surpass Ragin's (2008) thresholds; 0.740 and 0.450 for the consistency and coverage indicators, respectively.

Formulae of pathways (low formalisation of institutions)

Positive business customer experience exists under a unique configuration of causal conditions:

Pathway 1 (raw coverage = 0.538, unique coverage = 0.538, consistency = 0.876) consists of a combination of interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and service co-design that is a consistently sufficient pathway to achieve a positive level of Positive business customer experience.

5.3.2Sufficient conditions for subsample 2: high level of formalisation of institutionsWhen the level of formalisation of institutions is high (Table 4), the solution's overall consistency for positive BCX presence is 0.629 (> 0.740), and the overall solution coverage is 1.000 (> 0.450), both indicators above Ragin's (2008) recommended thresholds.

Formulae of pathways (high formalisation of institutions): (IC and CEG and SD) or (IC and ∼CEG and ∼SD) => BCX. A positive BCX exists under two equifinal configurations of causal conditions:

In pathway 1 (raw coverage = 0.486, unique coverage = 0.288, consistency = 1.000) a combination of interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and service co-design is sufficient to lead high levels of customer experience.

Pathway 2 (raw coverage = 0. 341, unique coverage = 0.143, consistency = 1.000) combines the presence of interfunctional coordination with the absence of customer engagement and service co-design. In this pathway, interfunctional coordination seems to play a significant role to achieve customer experience in compensating for the absence of customer engagement and service co-design.

The consistencies of the two complex configurations of causal conditions are above 0.75, indicating consistently sufficient pathways to BCX. Raw coverage score helps to assess the empirical relevance of each pathway (Table 4).

5.4Evaluation of the pathways (results of Study 3 and discussion)To assess the adoption by practitioners of the different pathways, we conducted a third study (Study 3: Online Focus Group-2) as indicated in the table of research design (Table 1. Appendix).

Results can be found in Table 5 (See Appendix). Based on the results, it can be concluded that the second pathway with the condition of interfunctional coordination and absence of customer engagement and absence of participation of service design is the solution that would be preferred based on these rating of the criteria: low complexity of implementation, low economic cost of implementation for the firm; high predisposition to the solution and medium positive impact on customer experience.

6Overall discussionThe first research question was related to the main antecedents of business customer experience and their relationships. We have found that the main antecedents are: interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and co-design of service and the relationships between these antecedents have been presented in a conceptual model.

The second research question referred to how institutions can moderate the antecedents of BCX, in that sense the moderator role of institutions has been demonstrated. This clearly reinforces the statement that value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements (Vargo & Lusch, 2016).

The third research question has been addressed using fsQCA with the identification of the main pathways to achieve BCX. Finally, the fourth research question related to how practitioners could adopt the different pathways has allowed us to shed light on the assessment of these pathways based on multicriteria analysis.

An interesting finding is the surprisingly high homogeneity of practices. This can confirm how institutional norms create similarities, or isomorphism (Dacin, 1997). This affects different actors of the analysed ecosystem in this paper. Regarding pharmacy stores as actors and beneficiaries of service provided by pharmaceutical distributors, this isomorphism mainly happened in the previous generation of pharmacy owners but, during the last five years, the opposite process is gaining momentum. In that sense, one of the most fascinating results is that what the previous generations of pharmacy owners (in most cases parents who started the business as first generation or a few cases that were second generation) might think is strongly influencing their business decisions towards service innovation. Another type of actors that are considered predominant key players in this ecosystem are the pharmaceutical distributors and this can be better understood considering contributions from Siltaloppi & Vargo (2014) who claim that institutional structures are often perceived as coercive forces that limit “free” agency. Moreover, it can be a signal of a radical transformation where the system of beliefs, assumptions, and ideas of the actors within the service system might be currently experiencing a total reconfiguration (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021).

Another finding, in further attempt to contribute to a better understanding of actors and resources in this ecosystem is the identification of four segments of customers, using a matrix awareness/participation in the service co-design (Table 6 Appendix). Segment 3 is the highest with 60% of customers (they are aware of their needs and level of knowledge and expertise about the co-design of core services, but surprisingly they are not actively participating in the design of those services). This finding can be interpreted considering previous findings from Simonson (2005) who demonstrated that customers who believe that they have strong, well-defined, and informed preferences are likely to place greater value on their participation in the process than are customers who are less sure that they know what they want.

Segment customers matrix

Another interesting finding that deserves further discussion is the concept formalisation/no formalisation of institutions. Hereto, contribution on this specific aspect of institutions has had little recognition. Recently Zhao et al. (2021) highlighted the need for improving the understanding of formalisation in relationships and Barry et al. (2021) also consider formalisation as a force affecting exchanges. Our contribution from the S-D logic perspective represents a theoretical contribution that we have been able to develop in collaboration with business experts and practitioners with managers to identify how the forms of human action are shaped, by social processes in which formal rules and informal social norms affect the way actors collaborate in value creation (Berger & Luckman, 1967; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2008).

It has been empirically proven that the level of formalisation of institutions moderates the causal configurations to enhance customer experience.

7Contributions, limitations and future researchOur contributions are twofold: first we develop an analytical framework of institutions and business customer experience in which the antecedents of BCX are: interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and participation in the service co-design. This model also incorporates institutions (the level of formalisation) as a possible moderator between the antecedents and BCX. The model contributes to the gap related to the need of midrange theories and models related to institutions and institutional arrangements. This model includes four research propositions. Second, using fsQCA, we empirically found pathways and conditions that can enhance business customer experience in two scenarios: low and high level of formalisations of institutions. In this sense, none of the antecedents of BCX can be considered necessary to lead BCX in either scenario. Additionally, the combination of interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and service co-design constitutes a sufficient pathway to achieve BCX (independently of the level of formalisation of the institution). On the other hand, the presence of interfunctional coordination with the absence of customer engagement and service co-design is a sufficient pathway to lead BCX only when the level of formalisation of institutions is high.

There are specific contributions to theory, to management and methodological.

7.1Contributions to theoryWe found in our critical review of the literature on the theme under investigation: (a) a lack of an integrative framework; (b) an absence of dialogue between theoretical contributions and data collected in field work research.

Although there are substantial contributions to comprehend the complex nature of value co-creation, literature has lacked an integrative framework to understand the role of institutions on customer experience and the relationships generated by customer engagement, interfunctional coordination and the participation in service co-design. Therefore, this paper contributes to expanding the understanding of customer experience in a B2B context.

The conceptual model as explained before can be considered per se a solid theoretical contribution.

In addition to the main contribution, which is the conceptual framework, this current research contributes to the notion of customer experience, with the identification of pathways using fsQCA (conditions and causal configuration) that lead to an enhancement of BCX.

Another contribution has been the identification of specific institutions in the pharmaceutical distribution sector that helps to make “visible” what Kostela-Huotari et al. (2021) coined as “invisible structure” within service systems.

In addition, this research contributes with the identification of three dimensions of institutions that require special attention: (1) the degree of formalisation (high/low or explicit/implicit); (2) degree of intentionality of the institutionalisation (intentional/nonintentional); (3) degree of how these institutions are relevant for the business (core vs peripheral).

Following Brodie and Peters (2020, p.2), the empirical approach frames the midrange theory, which is “context specific (…) and provides frameworks that can be used to undertake empirical observation and models to guide managerial practices”. This perspective builds the theory-practice gap (Fendt et al., 2008; Gummesson, 2017; Nenonen et al., 2017; Vargo & Lush, 2017), and frames the theoretical – empirical approach adopted in our work.

7.2Contributions to practitionersIn line with our first contribution to theory of the three identified dimensions of institutions, practitioners could firstly analyse their level of institutionalisation using the three dimensions (formalisation, intentionality, and relevance) and in a second stage focus on those who have already been formalised, that are intentional and, what is more important, that are core for their business.

Another interesting contribution to practitioners is the identification of four segments of business customers in relation to their participation on service co-design (see matrix awareness/participation shown in Table 6. Appendix) that should also contribute to expanding the conceptualisation of service systems transformations through service co-design. We suggest practitioners, especially to service providers, should give special consideration to segment 3 that can be described as having a high level of knowledge about what they need, the co-design of core services and low level of participation service co-design. It happens that is the biggest segment (60%) and with a huge opportunity cost.

Although none of the identified pathways seems to have a straightforward implementation, based on the third study of this research we found that the second pathway of the high level of formalisation of institutions is the one than could be preferred by practitioners.

Consultants may play a relevant role in the diffusion of best practices and institutions that can enhance customer experience.

7.3Methodological contributionsThis paper contributes also with a methodological novelty. There are no previous studies using moderation in fsQCA. A first attempt by Ragin & Fiss (2016) conducted separate analysis with four groups, black females, black males, white females, and white males, but it was not a non-dichotomous variable that they used as a moderator. To the best of our knowledge, our research is the first one conducting fsQCA using a moderating variable. It can be accepted that the division of our sample in two groups is parallel to the use of moderators in quantitative research. Therefore, it can be considered as a methodological contribution.

7.4LimitationsOne of the limitations of this research is that data were collected only from the pharmaceutical distributions sector. Another limitation is that, although the view from business customers and sector experts is important, future studies could include the perspective of service providers. And regarding the process to divide the samples for the moderation in a paper focused on methodological perspective, this could be discussed in more detail.

Another limitation may come from the use of fsQCA which, although it presents many benefits, there are no symmetric inferences like other symmetric traditional methods.

7.5Future researchOne first suggestion would be to investigate in different service sectors.

This research has utilised one of the dimensions of institutions that we have identified: the degree of formalisation. Future studies could also consider exploring the moderating role of institutions but using one or two of the other dimensions: degree of intentionality (Koskela-Huotari et al., 2021) and degree of relevance (core/peripheral).

Future studies could investigate customer experience also from the perspective of end customers and not only from business customers’ view.

The benefits of interfunctional coordination for resource integration seem clear from the results of this current work and from previous studies; however, the challenges and barriers of adoption should not be overlooked in future studies. In that sense, we suggest further investigations to examine how firms can minimise these barriers to increase interfunctional coordination that, consequently, as also shown is this paper, will have a positive effect on customer experience.

Another important area of research regarding interfunctional coordination is the effect of Covid-19 on workplaces practices as it was found (pre-pandemic) that working in physical proximity of colleagues allows for the development of informal networks and interactions (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007. This landscape has substantially changed with the pandemic. Therefore, firms need to adapt to address this new scenario and with the help of technological solutions to continue promotion interfunctional coordination for a better resource integration and, consequently, for value co-creation through institutions and institutional arrangements (Vargo & Lusch, 2016).

Siltaloppi & Vargo (2014) suggest that resource integration happens “here and now”, shaping the value proposition in a specific context. In our view, this clearly can relate to the Aristotelian concept of phronesis (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2011). As such, future studies could address from a virtue ethics perspective (Sison et al., 2017) how managers, and other key actors, develop and apply the virtue of prudence to integrate resources combining the benefit of all stakeholders.

In that sense, the study of business ethics from an S-D logic perspective would need to incorporate the institutions and institutional arrangements that will definitively contribute and facilitate the coordination amongst actors (Vargo & Lusch, 2017). This connects with virtue ethics as we should not forget that we are all human beings serving each other, through exchange, for mutual wellbeing (Vargo & Lusch, 2011); therefore, this interesting concept of virtue clearly leads to the concept of “attitude of service” of business leaders who can make a positive contribution to society if they understand service as an act of assistance that is done to help others through work (Guitian, 2015) and, in doing so, service can become a virtue, i.e., the habitual disposition to assist or help others. This author suggests a list of virtues that can enrich the quality of the service provided. It would be worth to investigate how these virtues or other similar ones can contribute to enhance customer experience.

8ConclusionIn conclusion, our research has developed a conceptual framework to understand the antecedents of business customer experience (BCX): interfunctional coordination, customer engagement and participation in co-design of services. Also, this model suggests institutions as a moderator of the antecedents and BCX. It can be concluded that relevant actors can enhance customer experience and co-create value. However, as happens with any attempt to develop a conceptual framework, there are always some questions that remain unanswered. What specific scale should be developed or adapted to measure and empirically test the different construct of our model? How significant are the proposed relationships between the variables? To what extent are institutions moderating the relationships between the variables? Is the chosen dimension of institutions (formalisation) comprehensive enough or should other dimensions be used to moderate? Are the identified pathways viable for practitioners? Will they find these pathways useful and feasible in terms of implementation?

We hope that future empirical studies can help to test and consequently improve this proposed model and the suggested research propositions.