Tourism services are particularly vulnerable to crises because of their hedonic and transitory nature. Notably, external crises have destination-wide negative impacts, which require a collective response usually led by governments for a more effective recovery. Despite the consensus on governments’ role and legitimacy in mitigating crises recovery, there is a dearth of research identifying these tools facilitating intervention and their effectiveness. Thus, the paper aims to explore various government crises mitigation strategies for the tourism industry. This research is based on a mixed-method approach. First, it explores government responses to crises through semi-structured interviews with industry stakeholders. Then, we conduct a survey to target industry experts and measure the effectiveness of government responses and their impact on various key performance indicators during crises. From an academic point of view, the research contributes to an understanding of the efficiency of different government recovery intervention methods, which are overlooked in crisis management theory. Based on managerial contributions, the study provides an effective design of the public tools for more crisis-immune businesses, where governments should prioritise managing external crises by establishing processes, standards, support services, information and communication.

Because of the hedonic and transitory nature of their products, tourism organisations are particularly sensitive to crises. The term crisis in the tourism industry usually refers to an event that leads to a shock, resulting in the sudden emergence of an adverse situation (Laws & Prideaux, 2005). Thus, Beirman (2003) cites five main causes for tourism sector crises, specific to destination: (1) international war or conflict and prolonged manifestations of internal conflict; (2) specific act(s) of terrorism, especially those directed at or affecting tourists; (3) a major criminal act or crime wave, especially when tourists are targeted; (4) a natural disaster, and finally in relation to our study, (5) health concerns related to epidemics and diseases. In this sense, in contrast to previous crises, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the tourism industry was much stronger because of its global scale and the widespread shutdown of travel and leisure activities (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). Given its global scale and sudden spread, Covid-19 triggered a wide range of government responses (Hale et al., 2021). Different countries initiated their own recovery strategies based on their own risk analysis (La Marca et al., 2020). The unprecedented global impact, uncoordinated travel restrictions, and quarantines also led the tourism and hospitality industries to a global halt (Wen et al., 2021). Facing complete quarantine for an extended period due to the new variants, it became clear that the industry would not survive without public support.

Considering the increasing frequency and impact of crises, both the tourism industry and public policy makers acknowledge the significance of government-designed mitigation strategies. These strategies might include individual strategies at the business level, such as privatisation, or public responses at the regional and national levels. Specifically, privatisation often shifts responsibility from the public to the private sector, potentially leading to more efficient and innovative services, but also posing challenges in regulation and equity. Decentralisation, on the other hand, can enhance local governance and tailor responses to regional needs, but it might also result in inconsistencies and coordination issues.

Previous research focused on organisation-specific responses and neglected the role and legitimacy of public policy to mitigate crisis impact on the industry. Exploring the success of different government crisis management strategies might result in more effective crisis management, better utilisation of public resources, and more crisis resilient tourism. Similarly, Boin et al. (2017) express that crisis management is thus an important policy area for political leaders, administrative executives, and public administration in general. Major crises strike at the core of democracy and governance, and hence constitute challenges not only for capacity but also for legitimacy and trust. Legitimacy in this context refers to the acceptance and justification of governmental authority by the public, which is critical for effective crisis response and recovery. The concept of legitimacy, whether it pertains to the government, state, politicians, or the country, is vital in understanding public trust and support for crisis management strategies. Díez-Martín et al. (2016, 2021) discuss the legitimacy of the state in relation to entrepreneurial capacity, highlighting the importance of public trust and institutional effectiveness. Applying this framework to the tourism industry permits an examination of how government legitimacy influences the success of crisis-mitigation efforts. Moreover, planning and preparing for the unexpected and unknown, dealing with uncertainty and ambiguity, tackling urgent issues, and responding to citizens’ demands and expectations are crucial and difficult tasks for public authorities (Christensen & Lægreid, 2020). Legitimacy is a key factor in reducing uncertainty and risk perception (Desai, 2008).

The sweeping and sudden spread of the pandemic caught tourism businesses unprepared. Lack of knowledge about the virus, new variants, and an inability to create scenarios because of its unprecedented nature (Martínez et al., 2021; Vázquez-Martínez et al., 2021) resulted in short-term trial-and-error and ad-hoc responses to the pandemic. Privatisation and decentralisation also affected government responses and most governments struggled to control the virus while keeping the economy alive (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). Limited capacity, late decisions, bureaucracy, inefficient responses, weak coordination and delivery are among the critiques of government measures during Covid-19 (Christensen & Lægreid, 2020).

Tourism is one of the most vulnerable industries to pandemics, because it involves mobility and human interaction (Baker et al., 2020). However, crisis management literature overlooked government responses to crises and their effectiveness in the industry. Without knowledge about the impact of their interventions, governments are criticized as inefficient and slow to address the needs of tourism organisations. These interventions also need to be tailored to business characteristics, the nature of tourism products, and market size (OECD, 2020), rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. For instance, most employment support targets large businesses addressing the heavy human concentration aspect of tourism and SMEs (Jones & Comfort, 2020).

Hence, the tourism and hospitality industries require much more customised government responses. Despite a consensus on the governments’ role and legitimacy in mitigating tourism recovery, particularly after Covid-19, there is a lack of research identifying these tools facilitating intervention and their effectiveness in future, crises which may include epidemics from zoonotic pathogens that are considered inevitable (Smith, 2021).

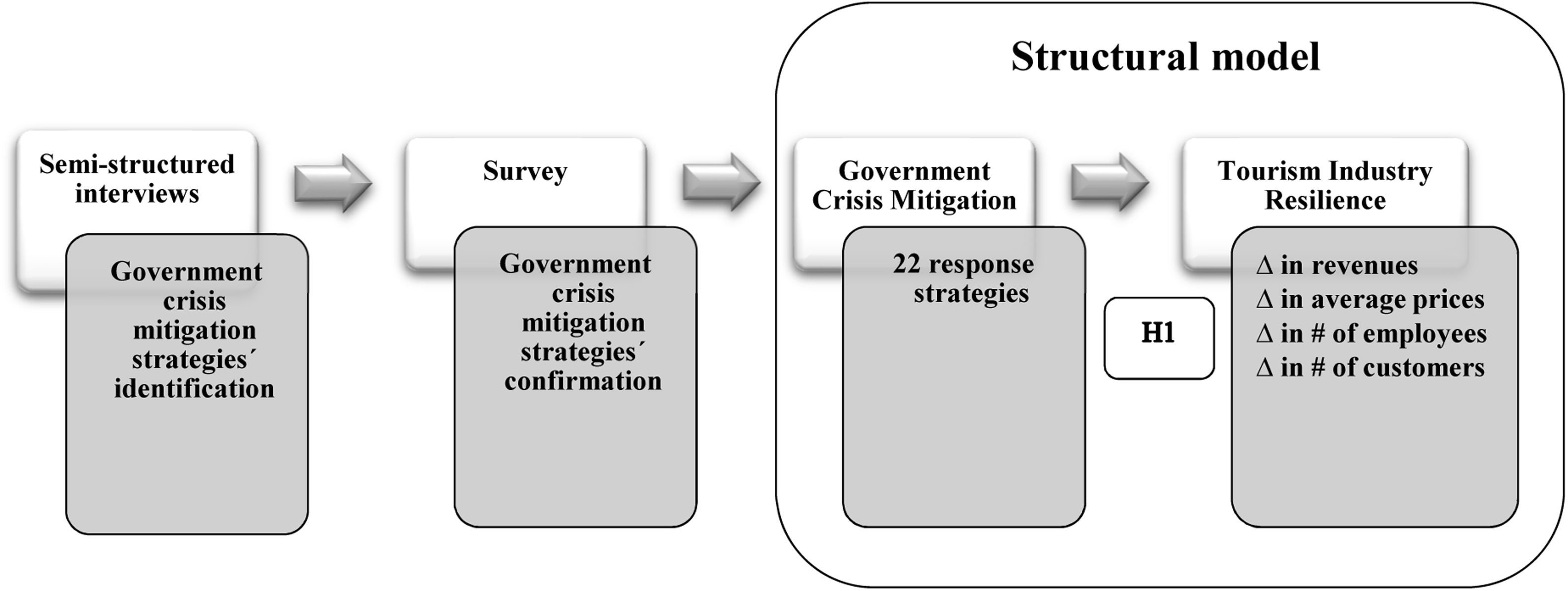

Thus, this paper aims to explore the government crisis-mitigation strategies for the tourism industry based on a mixed-method study. Covid-19 proved that some government responses may be more effective than others. In order measure their effectiveness, the first step is to identify an extensive list of alternative responses. At the initial qualitative stage, thirty tourism professionals were interviewed in three countries: Turkey, Malaysia, and Jordan, in order to identify government response strategies to crises.

These qualitative data were then used to create a questionnaire (inductive approach) using government interventions listed in the literature (deductive approach). The survey was than collected from 188 tourism experts, located in three different countries on four continents. Covid-19’s impact (on revenues, prices, customers, and employees) was also measured for each individual organisation, to measure the impact of government mitigation strategies. Despite the increasing frequency and magnitude of crises affecting tourism and the significance of government responses, little is known about the effectiveness of these mitigation strategies. Understanding the interface between government strategies and tourism organisations’ crisis performance will presumably inform crisis management theory and help governments design a more crises resilient and sustainable tourism industry.

The objective of this study is to explore how government crisis-mitigation strategies impact organisational performance within the tourism sector. It specifically aims to understand the effectiveness of these strategies in terms of changes in revenue, price, number of employees, and customer sales metrics between 2019 and 2022. Thus, the main research question is: how do government mitigation strategies affect organisational resilience and performance, as measured by changes in revenue, average daily room rates, number of employees, and occupancy? In other words, the paper focuses on a primary hypothesis (H1: Government crisis mitigation has a significant impact on organisational performance) and examines the loadings of each individual strategy. By concentrating on this single hypothesis, the study ensures clarity and precision, enabling rigorous testing of specific relationships, such as the impact of government crisis-mitigation strategies on the tourism sector's performance. This approach simplifies the research design by focusing on one hypothesis, making it easier to manage and control variables, thereby improving internal validity and reducing potential confounders. Consequently, the reliability of the conclusions is enhanced, as the findings are based on a clear and controlled examination, allowing for detailed analyses and robust insights that can directly inform and guide policy and decision-making processes.

In this context, the paper first provides a conceptual background and review of relevant and recent literature on crisis management, definition and types of crises, crisis management stages, and impacts on the tourism organisations. To follow, the governments’ role and legitimacy in crisis mitigation and its importance, processes, impacts, and strategies are discussed, based on the extant literature review. Qualitative and quantitative data collection tools, sampling, and analysis are described in the methodology section. Findings, theoretical and practical implications, and suggestions for future research are discussed at the end.

2Theoretical background2.1Tourism, crisis and recoveryNo matter their source, crises might trigger significant negative impacts on businesses depending on the scope, duration and size (Sonmez et al., 1994). The tourism industry has distinct characteristics (e.g., intangible, transitory, inseparable) and market structures (e.g., international, seasonality) with many interfaces among its stakeholders, creating an industry that is more vulnerable to crises. For the last decade, the countries we studied—Turkey, Malaysia, and Jordan—have been affected by different external crises. The global financial crisis in 2009 resulted in a 35 % devaluation of the Turkish lira (caused mainly by the US governments’ new tariffs and sanctions) with high inflation and interest rates, affecting the tourism sector in Turkey (Asgary & Ozdemir, 2020). The recent environmental crisis created by the earthquake on 6 February 2023 in central Turkey and northern Syria, which killed roughly 50,000 people, caused tourists to think twice before booking a trip to Turkey, a major Mediterranean holiday destination (Caglayan & Plucinska, 2023). Similarly, regional political instability in the Middle East and Ukraine has affected tourism demand in Turkey and Jordan (Oladipo & Plucinska, 2023). Jordan has always been a popular travel destination for people from all over the world because of its well-known historical sites, dynamic culture, and warm hospitality. However, due to surrounding regional wars and worldwide crises, the country's tourism industry is facing unheard-of difficulties (Mahadin, 2024). Since the late 1990s, the tourism industry in the Southeast Asian region has been subjected to several crises, accompanied by substantial declines in inbound tourism. Tourism in Malaysia emerged as vulnerable to regional and global events that act as triggers for tourism crises, demanding a response in which various strategies are employed (Zahed, Ahmad & Henderson, 2012). Consequently, the tourism industry in Malaysia also faced multiple challenges and difficulties during the pandemic crisis (Liu Zi Yuan, 2023).

Thus, governments are responsible not only for planning, regulation, legislation and facilitation of the tourism industry, but for managing and responding particularly to external crises. Considering the increasing frequency and magnitude of such global disruptions, political conflicts, natural disasters, epidemics and their economic outcomes (WTTC, 2019), governments should learn how to manage crises and mitigate their impact on the tourism industry (COMCEC, 2017).

Covid-19 proved the central role and legitimacy of the government in managing crises. Because crises have destination-level impacts on the tourism industry with various stakeholders and complex relationships, a collaborative response (e.g., hygiene standards) initiated by governments was required for a collective recovery at the destination level. On occasion, policymakers introduce immediate strict actions (9/11 in the US) or a wait-and-see reactive approach to avoid overreaction (Blake & Sinclair, 2003). During Covid, the majority of governments were criticised for poor judgement and timing, the duration of the crisis, and the outcome of public measures.

Acknowledging the inability of individual organisations to respond to such crises and withstand their impact in the long term, central management of such crises and the effectiveness of government initiatives become critical. Despite its significance, literature has so far failed to explore a comprehensive list of government crisis-mitigation strategies and measure their effectiveness for different businesses. Most research focuses on organisational responses, despite the inability of individual organisations to mitigate the impact of sudden, massive, external events.

Crisis-response strategies usually appear in three main phases: pre-crisis, mid-crisis, and post-crisis (Christensen et al., 2016). The government's role and legitimacy in preventative risk management (pre-crisis) is rarely acknowledged because of their subtler impacts (Moss, 2009). Because crisis-prevention is usually ignored, the government's role and legitimacy mid- and post-crisis and during recovery measures becomes essential. Yet, tourism crisis-management literature focuses either on the responses of individual destinations and sectors of the tourism industry (e.g., Aydogan et al., 2024) or the conceptual (ie., Jiang et al., 2019), neglecting the actual role and legitimacy of central governments. Some of these studies also list government support as an organisational strategy without detailing what is meant by government support, leaving a void in alternative government-mitigation strategies.

Scant research addressing government assistance (conducted before Covid-19) considers them part of the organisational response (e.g., Israeli & Reichel, 2003), overlooking the interface between their importance and organisational performance. Government response is also affected by the extent of the crisis impact (Denis & McConnell, 2003). No previous crisis matched the magnitude, duration, and global reach of Covid-19. Hence, most Covid-19 government-mitigation strategies are not included in scant crisis-management literature.

Focusing specifically on the COVID-19 crisis, Table 1 outlines various government responses related to tourism during the pandemic.

Literature references focusing on the government actions of managing Covid-19 impact in tourism industry.

| Authors | Year | Focus | Government actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Sharma et al., 2021) | 2021 | Reviving tourism post-COVID-19 | Financial aid, infrastructure development, marketing campaigns |

| (Carr, 2020) | 2020 | Impact on indigenous tourism in New Zealand | Emergency funding, cultural heritage preservation programs |

| (Gössling et al., 2020) | 2020 | Global impact assessment of COVID-19 on tourism | Travel restrictions, border controls, stimulus packages |

| (Hall et al., 2020) | 2020 | Promoting sustainable tourism practices | Sustainability incentives, destination management plans, crisis response protocols |

| (Sigala, 2020) | 2020 | Industry advancements and research resets | Research grants funding, industry regulations, public-private partnerships |

| (Zenker and Kock, 2020) | 2020 | Shaping future tourism research | Data collection initiatives, policy evaluations, collaborative research projects |

| (Brouder, 2020) | 2020 | Sustainable tourism transformations | Eco-certifications, tourism development grants, community-based tourism programs |

Source: own elaboration.

Considering government involvement, its duration, coverage and impact, the pandemic is one of the most suitable cases through which to explore governmental mitigation strategies and their effectiveness. The paper also examines these relationships across three major tourism destinations as the impact of Covid-19 began to wane, and the effectiveness of government responses. Therefore, this research provides more transferable knowledge than its few prior congeners, focusing on a single destination. Such knowledge is also important for a more sustainable tourism industry and a more effective use of public funds. Hence, the paper will not only identify these interventions, but also measure their effectiveness by matching them to organisations’ crisis performance.

2.2Legitimacy, crisis and recovery of the tourism sectorCovid-19 triggered an unprecedented spike in international tourism volume unseen since WWII. Including various epidemics, previous crises had regional, short-term complications for international tourism post-WWII. The mortgage crises of 2008-2009 evolved into an international economic crisis as well, but international global volume continued growing until 2020 (Yozcu & Cetin, 2019).

In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic posed unprecedented challenges to the tourism sector globally, necessitating swift and effective responses from governments to manage the crisis. The legitimacy of these governmental responses plays a crucial role in shaping public perception and compliance, which in turn affects the recovery and resilience of the tourism industry. Two new key studies underscore the importance of this legitimacy. First, Plaza-Casado et al. (2024) investigate the influence of country legitimacy on the internationalisation of emerging market multinationals. Their findings suggest that the perceived legitimacy of a country's actions significantly impacts its global economic engagements and trustworthiness, which are crucial for attracting international tourists during and after a crisis. When governments are seen as legitimate, it boosts international confidence and encourages travel, thus aiding in the recovery of the tourism sector.

Second, Blanco-González et al. (2023) examine the effects of social responsibility on legitimacy and revisit intention, with a focus on anxiety as a moderating factor. Their study examines how responsible and transparent government actions can enhance legitimacy, reduce public anxiety, and increase tourists' willingness to return. This framework is particularly relevant in understanding the dynamics of tourism recovery in the aftermath of Covid-19. Governments that act transparently and responsibly not only foster a sense of safety and trust among potential visitors, but also ensure long-term resilience of the tourism industry.

Large-scale quarantines, social distancing measures, closure of public spaces and travel bans prompted a major downturn in tourism activities (Bakar & Rosbi, 2020). One hundred fifty-seven destinations closed their borders in the wake of this historical, existential threat not only for individual organisations, but for the tourism industry. Optimistic calculations infer that at least 25 % of tourism businesses were bankrupt during Covid-19 (Crespí-Cladera et al., 2021). Tourism arrivals declined 72 % and 69 % in 2020 and 2021, respectively, compared to 2019. Though 2022 showed some signs of recovery, statistics reveal tourism volume was still well below 2019 numbers (-42%) (UNWTO, 2023). Based on predictions, international tourism is not expected to return to pre-Covid levels before 2024 (UNTWO, 2021). No tourism organisation can withstand such pressure indefinitely without government support. Moreover, legitimacy stands as a pivotal, sustainable, competitive advantage for both industrial and service-oriented enterprises, as highlighted by Miotto et al. (2020). It represents a dynamic capability that companies must adeptly manage to ensure success in their internationalisation endeavours, as emphasised by Rivero-Gutiérrez et al. (2023).

Hence, governments around the world have taken various initiatives in order to manage crises and eliminate the negative effects created by Covid-19 to protect the tourism industry and sustain its benefits to economy (e.g., employment, foreign exchange, multipliers, infrastructure development) (Aratuo et al., 2019). For example, with its indirect effects, tourism accounts for 19 % of the workforce in Jordan, 12 % in Malaysia, and 7 % in Turkey (COMCEC, 2019).

Pandemic crises, such as Covid-19, have multiplier effects through individual, organisational and societal shock channels, resulting in much deeper crises than previous pandemic episodes (Skare et al., 2021). However, the general trend in government response strategies was to implement short-term, local solutions, which is understandable given that no country can dictate inbound and outbound tourism unilaterally (Collins-Kreiner & Ram, 2021). Governments played an important role in the fight against Covid-19 on different levels, including the survival of the tourism industry. The size of a country's tourism sector typically correlated to the amount of economic stimulus aimed at mitigating the negative effects of Covid-19 (Khalid et al., 2021). Economic stimulus packages allow destinations to seize opportunities, support innovation, and redirect tourism in order to facilitate long-term favourable changes in both supply and demand.

Because tourism is a human-intensive activity, based on service interaction, the pandemic had an unprecedented impact on tourism relative to other industries and previous crises. Both governments and businesses took urgent measures due to the contagious nature of the pandemic (Huynh, 2020). The rapid spread of Covid-19 globally, its scope and length created a wide range of public responses (Hale et al., 2021) from governments, including very large interventions and support packages (e.g., tax reliefs, subsidies, deferrals of payments) (Prideaux et al., 2020) and employment contributions to prevent job losses (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). For example, the US released a USD 2 trillion recovery package to fund organisations who were hit the hardest, including airlines (OECD, 2020). Yet, the majority of tourism businesses are SMEs that are often not eligible for these recovery funds (Jones & Comfort, 2020). Moreover, conventional policy measures have changed the perception of the public health risks associated with travel (Hassan & Soliman, 2021). In particular, the business travel and MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Events) sector are still suffering even after the lifting of restrictions.

These government mitigation measures can be grouped into four clusters. Financial and fiscal measures (i) include credit and loan facilitation, credit holidays, grants and cashflow support, deferrals of payments, rent subsidies, government guarantees on loans, deferrals of energy/communication/utilities charges, tax exemptions, conversion of distressed loans into tax credits, waiving of cancellation fees, and acceleration of depreciation. Many governments focused on providing financial relief to tourism organisations, in order to help them survive the crisis in the short-term (AIEST, 2020; OECD, 2020).

As a human-intensive sector, tourism is also an important source of employment, particularly in developing countries. In order to protect tourism jobs, governments also introduced (ii) employment subsidies, such as unemployment support, salary subsidies, and social security fee waivers. Some support was provided for the self-employed in tourism, where SMEs account for a large portion of the industry.

Various strategies were also utilized by governments in order facilitate demand (iii); subsidised recreational vouchers, promoting domestic travel, facilitating travel insurance systems, creating travel bubbles, information provision, product and market diversification, promoting and restoring the image of safe destinations were among the strategies adopted in this respect.

Finally, there is operational and non-financial support (iv), such as establishing hygiene standards, providing protective supplies, issuing safe tourism certificates, disinfecting and sanitising facilities, emergency medical support, establishing crises response committees, and providing information and contact tracing services (AIEST, 2020; OECD, 2020).

Government recovery measures can also be grouped under direct and indirect responses. For example, social distance measures can be considered an indirect measure as it does not directly target the tourism industry. However, some of these measures had significant impact on tourism volume. On the other hand, some responses directly targeted the tourism industry, such as creating travel bubbles or prioritising vaccinations for tourism staff. Beyond the immediate measures to contain the virus, governments introduced measures targeting first survival, then recovery, and finally resilience. Hence, government interventions may be divided into short-term survival (e.g., cancellation refund delays), mid-term recovery (e.g., cheap credits), and long-term immunity responses (e.g., market diversification) (COMCEC, 2021). These strategies are displayed as a matrix in Fig. 1.

Government Mitigation Matrix (Reactive – Recovery - Immunity). Source: Adapted from COMCEC (2021); OECD (2020)

Despite the numerous government mitigation strategies employed during the crisis to aid tourism recovery, these strategies have not been consolidated in a single study, nor has their importance or impact on organisational performance been assessed. Identifying and measuring the effectiveness of these strategies could inform public crisis-management policies and align them with organisational performance, leading to a more selective use of crisis-management resources.

3MethodologyThis research aims first to identify an extensive list of actual and potential government crisis-mitigation strategies affecting the tourism industry, and second to measure their effectiveness based on the perspectives of tourism professionals and organisational performance. Because theoretical foundations of government crisis-management strategies are scant, the study takes both an inductive (interviews with experts) and a deductive approach (reviewing literature) to identify these central mitigation strategies. The effectiveness of the recovery strategies was measured with a survey, designed according to the content analysis of semi-structured interviews with experts.

Turkey, Malaysia, and Jordan were selected given their sizeable tourism sectors and frequent experience with crises, making them exemplary cases for studying government-mitigation strategies. In the initial qualitative stage, 30 interviews with industry stakeholders in these countries examined government crisis interventions. As displayed in Table 2, most respondents were male (21); they were 46 years old, and had an average of 23 years’ experience in the tourism industry. Respondents worked in different sectors of the tourism industry, including lodging (10), tour operation (6), catering (6), event management (5), and transportation (3). They were mainly located in Turkey (14), Jordan (9), and Malaysia (7).

Interview respondent profile.

Source: own elaboration.

These nations generate a substantial portion of their GDP from tourism and frequently face economic crises, natural disasters, military coups, terrorism, and epidemics. Additionally, their geopolitical positions in conflict-prone regions lead to frequent external political unrest. Despite these challenges, they have succeeded in becoming major international tourist destinations, a success that can be partially attributed to effective government crisis-management strategies (COMCEC, 2021). The impact of Covid-19 on these countries, including sharp declines in tourism revenue, job losses, and business closures, underscores the relevance of this study. The insights gained are valuable for informing global tourism crisis-management, with findings applicable to other countries facing similar challenges. By incorporating a broader range of crises, including economic downturns and natural disasters, this study enhances the theoretical framework, making the research relevant to a wide array of tourism-dependent nations.

In addition to demographic (e.g. age, gender, experience) and organisational (e.g. sector) enquiries, the semi-structured interviews include questions about the impact of Covid-19, the government's role in short and long term, public response strategies and their effectiveness, crisis resiliency and its indicators. Interviews were conducted both online (21) and in person (9), depending on the availability and preference of the participants. A mix of purposive and snowball sampling was used and respondents were asked to suggest other potential participants at the end of each interview.

All interviews were digitally recorded with informed consent and transcribed verbatim after each interview. Respondents were also given numbers (i.e. R1) to protect their anonymity. After 30 interviews, the data started to repeat itself and the authors agreed, due to data saturation, that no new interview would result in additional mitigation strategies (Saunders et al., 2018). The interviews were conducted between March and May 2022 and took 42 min on average. Ten years of tourism industry experience was set as a criterion for executives, in order to collect deeper insights on government mitigation strategies, based on the respondents’ experiences and previous crises. This phenomenological approach helped the authors collect a rich and diverse set of government mitigation strategies based on the real expertise of the respondents.

Data was then content-analysed based on open-coding procedures, colour coded by each author, and a pool of government strategies were identified. These strategies were then merged with the strategies identified from the literature review (e.g. Baker et al., 2020; Boin et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2016; Blanco-González et al., 2023; Plaza-Casado et al., 2024) and reports, such as WTTC (2021); COMCEC (2021); OECD (2020). After the pool of government strategies were identified based both on interview findings and related literature, some of these were found irrelevant, addressing general economy or health measures (e.g. lock downs); some were considered too similar and merged into one strategy. At the end of this process (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), a total of 30 government crisis-mitigation strategies were identified. The interviews (inductive approach) offered novel strategies that were missed in the literature during the deductive process, such as seat support for airlines, low-set exchange rate policies, vaccination priority for tourism staff, and so on. Hence, the paper also introduces these overlooked strategies into the theory of risk and crisis management in tourism.

After the identification of these actual and potential interventions, a self-administered survey was designed to measure their importance on different types of tourism organisations. During this second stage, questionnaires were first pilot-tested on 50 tourism executives in order to receive their feedback, improve face validity, and investigate for loading of the items. Based on feedback from the pilot test, some re-wording suggestions (banning layoffs vs. suspension of layoffs) from the respondents, were honoured. Because of their high covariance, two strategies (cheap credits and loan guarantees) were also merged into one (subsidised credits), generating a final list of 29 strategies to be used in the survey.

The quantitative data was collected in the case countries from tourism professionals representing different sectors of the industry (lodging, transportation, tour operation, restaurants, and events). Quantitative data collection took two stages and two months, between May and July 2022. During the first stage, a total of 143 valid responses were received. In addition to the authors’ own networks, the questionnaires were also distributed by NTOs in Turkey, Jordan, and Malaysia and sent as an online survey to their stakeholders printed in several newsletters and/or published on their official websites. In the second stage, professional associations were also involved (e.g., Hotel & Restaurant Associations) and an additional 45 responses were recorded, for a total of 188 valid questionnaires collected from three major tourism destinations: Malaysia (76), Turkey (74) and Jordan (38). The respondents represented tour operation (88), lodging (76), food and beverage (10), and other (14) (e.g., conference centres, attractions, events) sectors. Eighty-six respondents were from SMEs with less than 50 employees, 82 represented mid-size tourism organisations employing between 51-250 employees, and finally 20 organisations had more than 250 employees, qualifying as large tourism companies.

A five-point Likert-type scale was used to measure the effectiveness of the 29 government strategies. Organisational crisis resiliency was measured by the percentage change in four indicators, including (i) revenue, (ii) price, (iii) no. of employees, and (iv) no. of customers. Because the respondents were asked to compare these indicators based on 2019 (peak tourism demand) and 2022 (base tourism demand) numbers, all four performance indicators experienced a decline with negative percentage changes. These performance indicators were also identified based on interviews and extant literature (ie. Aydogan et al., 2024). Structural equation modelling was used to test the hypothesis. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) method was used to estimate the model and structural model. The PLS method is sufficient to determine structural equation modelling and is recognised as more suitable for analysing small samples and complex models with multiple constructs, making it well-suited for the 188 responses gathered (Hair et al., 2017). PLS was performed to determine the significance levels of factor loadings and path coefficients, and bootstrapping was performed to identify the significance of the hypothesis.

The model examines the impact of 29 government crisis-mitigation strategies on organisational performance in the tourism sector, specifically looking at changes in revenue, price, number of employees, and customers between 2019 and 2022. PLS was chosen over traditional regression techniques due to its ability to manage multiple independent and dependent variables, handle latent constructs, and facilitate the path analysis of both direct and indirect effects (Chin et al., 2008). This approach provides a robust and comprehensive analysis of the interrelationships between government strategies and organisational performance.

Finally, blindfolding was used to determine the Q2 values (Ali et al., 2018). The conceptual framework of the paper to analyse the interrelationships of the investigated government-mitigation variables is displayed in Fig. 2.

4Results4.1Qualitative findingsBased on a thematic content analysis of the interviews and extant literature, a pool of 30 strategies was identified. These strategies can be grouped into four main categories. The first group of government crisis-mitigation actions aim to (i) facilitate demand and include such strategies as providing holiday credits and extending bank holidays to encourage local domestic travel among citizens; international lobbying activities and destination promotion activities were also used to enhance overall tourism demand during the crisis.

Also important is (ii) public financial support, considering the extended periods of lock-down during the crises. These government strategies include tax holidays and discounts, bank loan guarantees, low exchange rate policies to attract international demand, seat support for flights, rent support for facilities, deferrals of utility (i.e. water, energy) charges, accelerated depreciation options, renovation support, digitisation and automation support to minimise human contact, the advanced purchase of travel services to be used later by governments, and cheap credits.

Tourism is also a human-intensive service, and interaction with staff is an important part of the travel experience (Yarcan & Cetin, 2021). In order to (iii) maintain and train the tourism personnel during the crisis, various government subsidies were offered to tourism organisations, such as salary contributions, wage subsidies, reduced social security contributions, suspension of layoffs, and human resources training support.

Various (iv) operational and legislative actions were also adopted by governments to minimise the impact of the crisis and keep the tourism industry afloat. These included holiday insurances, softening legislation on bankruptcy, introducing vaccine passports to facilitate travel, cancellation refund delay opportunities for advanced payments, safe tourism certifications, medical support services, hygiene and capacity audits, safe travel bubbles, vaccination priority for tourism staff, and advisory and information services.

Finally, respondents were also asked about crisis resiliency indicators. Various keywords including sales, revenue, occupancy rates, number of customers served, capacity utilisation, table turnover, number of employees, average daily rates, prices, net operating income, and profit were mentioned as potential crisis resiliency indicators, some of which (e.g. table turnover, room occupancy) are industry specific. For the sake of universal measurement applicable to all tourism organisations, these were also merged into four main crisis resiliency indicators: (i) revenue, (ii) price, (iii) number of customers, and (iv) number of employees.

4.2Quantitative findingsTable 2 demonstrates the descriptive statistics for the items and constructs. Overall, the mean score for government response strategies (role and legitimacy) was calculated at 3.89. Vaccine priority for tourism staff (M: 4.23), wage subsidies (M: 4.09), medical support services (M: 4.05), safe travel bubbles (M: 4.05), and vaccine passports (M: 4.03) received the highest ratings, while accelerated depreciation (M: 3.46), renovation support (M: 3.47), favourable exchange rate policy (M: 3.67), advanced public purchase of travel (M: 3.70), and holiday insurance (3 M:.72) were calculated as the least effective government strategies. Considering crisis resiliency, the average of four crisis resiliency indicators declined by 56.3 % during Covid-19. Revenue (DR) experienced a 68.8 % decline, whereas the number of customers (DNC) decreased by 67.8 %. The number of employees (DNE) (48.1) and average prices (DAP) (40.5 %) also experienced significant downturns considering pre- and post-crisis performance.

In order to identify the contribution of individual strategies on government mitigation (GOV) and measure the impact of those strategies on the crisis resiliency (CS) indicators of organisations, a structural model was also designed, as displayed in Fig. 3. To evaluate the measurement model, outer loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability were examined. Convergent validity was tested through factor loadings, AVE and CR (Hair et al., 2017). During the path analysis, seven items from government mitigation strategies were dropped because of their weak loadings. Factor loading greater than 0.70 is believed to provide statistical significance and the model fit (Hair et al., 2017). Table 3 shows that all outer loadings are above 0.722 and thus within the recommended values (Hair et al., 2017). AVE values are also higher than the 0.5 threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), as displayed in Table 3. Cronbach's Alpha values are above 0.8 and CR values (min. 0.862) are within the recommended margins (Hair et al., 2017).

Measurement model.

Source: own elaboration.

Considering the size of government mitigation strategies, outer loadings indicate the reliability of strategies and their commonalities with the government mitigation strategies construct, these were also reported. Digitisation/automation support (0.894), medical support services (0.888), subsidised credits (0.871), deferrals of utility charges (0.870), tax holidays and discounts (0.868), advisory and information services (0.855), advanced public purchase of travel services (0.853), and wage subsidies (0.845) retained the highest commonalities under the government mitigation strategies construct. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) (Ali et al., 2018). HTMT values should be below 0.9 (Gold et al., 2001). As shown in Table 4, all HTMT values (0.165) are well below the threshold, indicating that discriminant validity is established.

To test the significance of path coefficients and assess the hypothesised relationship, the bootstrapping method was conducted with 5,000 iterations. As shown in Table 5, government mitigation strategies have a significant impact on the crisis resiliency of tourism organisations (β = -0.202, p < 0.05). Because the resiliency was measured using pre- and post-crisis changes in revenue, price, number of employees and customers, the beta coefficient is negative. In addition, the f2 size effect was medium (0.15 < f2 < 0.35).

Hypothesis testing.

| Hypotheses | β | t- Statistics | Decision | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: GOV → RC | -0.202 | 1.987* | Supported | 0.032 |

Source: own elaboration.

Criterion for predictive relevance was tested with the predictive sample reuse technique (Chin et al., 2008). As seen in Fig. 3, Q2 for tourism industry resilience is 0.013, within the recommended values (Hair et al., 2017). Government mitigation strategies also explain around three percent of tourism industry resilience (R2 = 0.031).

5DiscussionDuring Covid-19, economies and businesses relied heavily on government stimulus packages and interventions to survive (Kuscer et al., 2022). The tourism and hospitality industries were no exception. Various governmental supports were introduced to keep the industry afloat, while introducing social-distancing measures and restrictions on mobility (Nunkoo et al., 2022). The strengthening of organisational resilience is important for the tourism industry to better respond to the impact of crises, such as Covid-19 and, therefore recover better from the fallout (Okafor et al., 2021). Economies can enhance the resilience of their tourism industries by implementing targeted crisis-mitigation strategies.

This research not only identifies a comprehensive list of potential government responses to crises, but also measures their effectiveness and impact on organisational resiliency within the tourism industry. Findings suggest government mitigation strategies affect resiliency in tourism at the individual business level. Understanding which response strategies are more effective under what conditions might improve the use of public resources and result in more effective central crisis management and a resilient tourism industry. Based on the responses to a qualitative enquiry, 30 mitigation measures were identified, which were pilot-tested and reduced to 29. After quantitative data collection and analysis, seven of these were dropped and the remaining 22 strategies were grouped into government mitigation strategies.

Operational measures such as vaccination priority provided for tourism staff, medical support services, such as hotlines, safe travel bubbles, and vaccine passports received the highest ratings from respondents. Stimulus packages targeting employment, such as wage subsidies, were also considered important in tourism as a human-intensive service. The rest of the interventions also received above average ratings. The study also measured organisational crisis resiliency by surveying declines in revenue, price, number of staff and customers. The findings suggest significant declines in all of these measures. In the final stage, the impact of government intervention on organisational resiliency was measured through path analysis, producing significant results. The theoretical and practical contributions are discussed in the next sections.

6Conclusions: contributions, future studies, and limitations6.1Theoretical contributionsRealising the importance of government mitigation, some international organisations prepared various industry reports (e.g., COMCEC, 2021; OECD, 2020; WTTC, 2021) on the subject based on secondary data, yet these merely list organisational responses at best, without providing any real insight about their effectiveness. Scarce academic research mentioning government response strategies focused on the lodging sector (e.g., Israeli & Reichel, 2003).

This paper collected its data from a wide range of tourism organisations (lodging, tour operation, catering, event management, transportation). Despite various industry reports and literature mentioning these strategies in some degree, no empirical study has been conducted post-Covid on government mitigation strategies from a holistic perspective, nor has their effectiveness based on user data been assessed. In addition to offering a much more representative list of government mitigation strategies based on inductive (interviews) and deductive (literature and industry reports) approaches, this research also evaluates the effectiveness of government strategies by matching them with organisational performance and comparing the pre- and post-Covid performance indicators based on a survey.

Crises in tourism can also be seen as opportunities, and can lead to transformations and positive results by creating new experiences, knowledge, relationships, networks, innovations, and policies (e.g. Bulchand-Gidumal, 2022). Just like malfunctioning machinery, we must first turn tourism off to identify and fix its problems. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic prompted governments to reassess their tourism industries, catalysing a transition towards sustainable development. Destinations are actively diversifying their market focus, enhancing governmental support and financial allocations, and pioneering innovative products and policies (Blackman & Ritchie, 2008). Notably, the scrutiny of cultural tourism policies sheds light on how Covid-19 shaped the behaviour of cultural tourists, providing indispensable knowledge for creating customised tourism strategies. Through the implementation of highly customised marketing approaches, especially tailored to heritage destinations, satisfaction levels within this demographic can be notably enhanced, even in challenging crisis scenarios (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2024).

Some unhealthy operations and organisations that undermine the development and competitiveness of destinations were eliminated. For example, informal organisations, disturbing market dynamics were not permitted to benefit from government support and ceased their operations. That being said, government support should not create competitive advantages by favouring some organisations over others. There may be instances where government support is abused and used to create unfair advantages. This happened in the airline industry where most governments favoured their flag carriers, while overlooking the needs of their low-cost counterparts, disturbing the market economy.

The paper offers some clues about the impact of Covid-19 on the tourism business. Revenue (68.8 %), number of customers (67.8 %), number of employees (48.1), and average prices (40.5 %) all declined relative to pre- and post-crisis performance. This is also a novel finding, as previous papers focused on secondary performance indicators (e.g., Ribeiro et al., 2019) published elsewhere (e.g., sales, ROI). Although these might be considered more objective measures, they fail to provide real insight into the impact of crises on tourism. For example, although it is self-reported and somewhat subjective, our study shows that despite significant declines in revenue and number of customers, tourism organisations preferred to conserve their HR and restrain price discounts. Qualified and experienced employees are seen as a competitive advantage in the tourism industry (Lai & Wong, 2020). Loosing such a workforce proved very challenging after Covid-19. Moreover, price declines had long-term effects on brand image. An inability to create incremental demand resulted in a surplus (Cetin et al., 2016) for a limited existing customer base given mobility restrictions. Hence, price and the number of staff decreased less than revenue and the number of customers. This distinction in the type of impact on tourism is also novel in crisis management literature.

Most government mitigation research was conducted in developed countries and usually on the overall economy (e.g., Kapeller et al., 2018) prior to Covid-19. There is scant research addressing government recovery strategies in developing countries. Since developed countries tend to have large financial resources and advanced administrative capabilities, they were more able than emerging economies to design and implement programmes to combat the effects of the Covid-19 (Khalid et al., 2021). Most tourism-dependent economies adopted greater economic incentives to reduce the negative effects of the Covid-19 epidemic on employment, income generation, standard of living, and economic growth. Using data from Jordan, Malaysia, and Turkey, as emerging destinations and developing economies, this study sheds light on government responses to Covid-19 in the tourism industry of developing countries.

Our study also integrates the concept of legitimacy into the tourism crisis and recovery literature. By incorporating theoretical insights from Plaza-Casado et al. (2024) and Blanco-González et al. (2023), we expand the understanding of how the perceived legitimacy of government actions influences tourism recovery and resilience.

6.2Practical implicationsConsidering the increasing frequency and magnitude of external crises, exploring different government interventions and their effectiveness is critical. Even if individual businesses have established crisis-management plans and processes, only a few organisations can resist the impact of global crisis like Covid-19. Hence, an effective public response would not only result in the better use of public resources, but would also promote the creation of crisis-resilient destinations. Informed by the literature and empirical research, this paper includes an extensive list of government crisis intervention measures as regards their duration (short-mid-long term, survival/recovery/immunity) and impact (direct and indirect) on the tourism industry. Moreover, this research confirmed the positive impact of government interventions on the crisis resiliency of the tourism industry.

The effectiveness of government mitigation strategies was also measured based on ratings from tourism industry stakeholders. The findings revealed that all government mitigation strategies were considered significant by experts. However, they rated operational measures (e.g., vaccination priority for tourism staff) and mitigation strategies targeting human resources (e.g., wage subsidies) as most effective. Most financial (e.g., accelerated depreciation) and promotional (e.g., holiday insurance) mitigation strategies were deemed less important. Hence, professionals recognise the government's role and legitimacy in overseeing the collective management and operation of crises. By examining the impact of legitimacy in governmental responses, our research provides actionable insights for policymakers in the tourism sector. It highlights the necessity for transparent and responsible actions to build trust and ensure compliance among the public, which is crucial for the effective management of tourism crises (Blanco-González et al., 2023; Plaza-Casado et al., 2024).

Considering tourism is a human-intensive service, facilities designed to preserve existing human resources were also recognised as important. Most financial instruments were earmarked and postponed collection rather than defer payments altogether. For example, accelerated depreciation meant organisations could deduct full depreciation expenses within the same year instead of future terms. Although such tools were still rated important and provided some relief, they were considered less effective. Finally, some strategies focusing on encouraging demand were also perceived less important, like holiday insurances, as they did not have much impact on overall demand, given mobility restrictions.

Thus, governments should prioritise the management of external crises by setting up comprehensive processes, standards, support services, information provision, and communication channels. Immediate response measures, such as wage subsidies, salary, and social security contributions are essential for maintaining the workforce. Financial support mechanisms, including subsidised credits, loan guarantees, tax holidays, and deferrals, are crucial for short-term recovery. Long-term strategies, such as favourable exchange policies, advanced public purchase of travel services, destination promotion, and facilitation of demand, should be considered to build resilience. Because crises rarely happen in isolation (Marine-Roig & Huertas, 2020), countries need to be able to design and implement a collective response. Though the WTO (World Tourism Organisation) is an international organisation represented by countries on governmental level, the efficiency of collective responses compared to other international organisations (e.g., WHO) is questionable. Consequently, a more coordinated response on an international level is needed.

Though our study did not include an examination of the social dimension, specifically, inclusive politics for the government's future mitigation strategies for the tourism industry amid crisis management, it is important to consider some inclusive politics, such as collaborative frameworks, in order to foster cooperation between government agencies, tourism organisations, and local communities by establishing crisis management groups, inclusive decision-making involving marginalised groups and vulnerable populations in crisis planning, capacity building for training tourism reps and local communities in crisis response, and effective communication channels that establish clear and transparent communication during crises with the media, travellers, tourism organisations, and local residents.

Several factors can affect the nature of government support for tourism during crises. These may relate to the nature of the crisis or the features of the destination. In the case of Covid-19, for example, the spread of the virus and the health service's infrastructure affected most government attempts to contain the crisis (Cambra-Fierro et al., 2022). The characteristics of the tourism product at the destination (e.g. urban – rural), the target markets, the share of tourism in GDP, the organisational structure of supply (e.g. SMEs) and so on, should all be considered.

During Covid-19, the tourism industry experienced an unprecedented crisis, resulting in sharp and significant declines in demand (-72 %). Some organisations had to cease their operations and liquidate; hence, they are not included in the study. Future longitudinal research could explore the impact of government recovery strategies by utilizing secondary data to assess the long-term effects of government support on organisational and destination performance. This approach underscores the importance of continuous research and monitoring to evaluate the effectiveness of implemented strategies. By engaging in ongoing research, governments can better assess the impact of their interventions, adapt to evolving circumstances, and make evidence-based decisions. Encouraging investment in data collection and analysis will enable governments to refine and adapt their interventions based on empirical evidence, ultimately enhancing the overall effectiveness of their response.

Thus, individual solutions and strategies may be implemented for different regions and crisis characteristics. Other criteria also affect organisational performance during crises (Paraskevas et al., 2021). In particular, organisational characteristics, such as size (Brown et al., 2018), location (Ngin et al., 2020), organisational culture (Liu-Lastres et al., 2023), target markets (Do et al., 2022), capital structure (Whitman et al., 2014), and so on may significantly influence how crises affect the performance of tourism organisations. Hence, future studies might look into the mediating and moderating effects of such organisational and market characteristics on the relationship between government mitigation and organisational performance. This approach is essential because it allows for a deeper understanding of how factors such as organisational structure, size, and market dynamics influence the effectiveness of government interventions on organisational outcomes. By exploring these mechanisms, researchers can uncover the intricate pathways through which government actions impact performance metrics like profitability, innovation, and resilience. Understanding these dynamics is critical for both academics and practitioners, as it provides actionable insights for optimising organisational strategies in response to government policies. Similar studies might also be conducted in other industries (e.g., manufacturing) to identify government mitigation strategies and measure their effectiveness.

As a final remark, it is worth mentioning that one of the limitations of our study is the small R-squared value observed in our model. This low explanatory power indicates that the model does not capture a significant portion of the variance in the dependent variable, suggesting that other unmeasured factors may play a substantial role. While this highlights the complexity of the research problem, it also underscores the need for future research to incorporate additional variables or employ more sophisticated modelling techniques to better understand the underlying dynamics.

Disclosure statementThere are no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

All authors have approved the final article.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSevinc Goktepe: Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Gurel Cetin: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Arta Antonovica: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Javier de Esteban Curiel: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

This study was supported by TUBITAK (BIDEB-2219) and Istanbul University Scientific Research Coordination Unit (IU-BAP / SBG-2020-36800). TUBITAK fund was approved based on a proposal designed for a generic call for international projects and IU-BAP fund was used to finance mainly the national data collection.