This paper seeks to develop a theoretical model to explain the role of knowledge integration and knowledge options in the case of external knowledge acquisition via employee training.

It considers types of knowledge acquired through specific or general training and heterogeneous or homogeneous production processes at companies. It also considers the possibility of opportunistic behaviour by trained employees. We propose key conditions that companies should consider when they acquire external knowledge by means of training.

Insights are given into the process of and success conditions for dynamic value creation due to the adoption and the internal sharing of knowledge. Even at this early stage our theoretical model provides guidelines for decision-makers as to how to improve investments in training issues. The model leads to several propositions and provides a starting point for developing hypotheses that can be contrasted empirically in further research.

Companies need to develop innovation in products, processes and organisational structures to obtain and maintain a competitive advantage. A company can thus be considered as a knowledge producer, or a learning organisation (Kushwaha & Rao, 2017; Tsoukas & Mylonopoulos, 2004).

Small and medium-sized enterprises often lack the critical mass needed to create the knowledge that can enable them to maintain their businesses sustainably, but large companies also frequently find themselves unable to develop by themselves all the knowledge that need to be competitive in all activities in which they are involved. One solution to these problems is to obtain external knowledge (Barney, 1991). So to perform better in terms of innovation, companies must cooperate with knowledge providers (Emden-Grand, Calantone, & Droge, 2006) or obtain knowledge externally by sourcing (Kogut & Zander, 1992) or by acquisition (Veugelers & Cassiman, 1999). One way to acquire external knowledge is employee training. Knowledge-oriented human resource policies such as training have a moderating effect in the relationship between knowledge exploitation and innovation performance (Akay & Kunday, 2018; Donate & Guadamillas, 2015). Moreover, several empirical studies (e.g., Bartel, 2000; Huselid & Becker, 1996) show that the contribution of employee training to the results of companies is even greater than expected under the human capital models developed by Mincer (1962) and Schultz (1963). One reason for this may be that knowledge may represent a real option for companies. The knowledge acquired by means of training therefore enables other knowledge and skill-sets to be developed in the future (Berk & Kaše, 2010; Wang & Lim, 2008).

We focus here on the joint analysis of these aspects: a theoretical model is developed that includes the effects of integrating new knowledge acquired via training into the range of knowledge already in place in the firm and the consequences of the real options generated by that new knowledge. A distinction is drawn between two types of acquired knowledge, specific and general and two types of companies, depending on whether their production processes are heterogeneous or homogeneous. Our model identifies key factors and conditions for a company to consider when investing in training courses for its employees.

The next section addresses the problems to be considered, particularly the importance of training as a source of competitive advantage. It also reflects the real options generated using the new knowledge acquired through training. Our model is set out in Section 3. The results are then discussed by applying them to four hypothetical cases of firms that differ in their production processes and in the types of knowledge provided by training. Finally the conclusions are set out, along with the managerial implications as regards training policies that increase their possibilities of generating competitive advantages. Possible areas for future research are also discussed.

2Employee training, competitive advantage and knowledge optionsNumerous studies have found a positive relationship between training and different variables representative of company success, such as sales (Bartel, 2000), employee productivity (Bartel, 1994), profitability (Bartel, 2000; D’Arcimocles, 1997; Huselid & Becker, 1996), stock market performance (García-Zambrano, Rodríguez-Castellanos, & García-Merino, 2018; Molina & Ortega, 2003), above average profits for the sector (Calzarrosa & Gelenbe, 2004; McGahan & Porter, 2003) and a combination of variables (Aragón, Barba, & Sanz, 2003; Danvila & Sastre, 2009; Goval & Welch, 2004).

In particular specific knowledge has become more important, given ever-greater pressure to increase productivity. Several authors propose that companies should mainly invest in training that provides specific knowledge, as it is difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991). However, companies could be reluctant to invest in either specific or generic training because training can increase employees’ bargaining power with a view to obtaining higher salaries (Rajan & Zingales, 1998).

Nevertheless, certain empirical studies show that the contribution of training to the results of companies is in reality even greater than expected according to human capital models (e.g., Bartel, 2000; Huselid & Becker, 1996). This can be explained by the fact that certain knowledge may represent – according to the Real Options Approach (Amram & Kulatilaka, 1999) which is based on the option pricing methodology (Black & Scholes, 1973) – a real option for companies. The knowledge acquired by means of training therefore enables other knowledge and skill-sets to be developed in the future. Different option categories can also be found in assets of any type, and this is especially so in the case of knowledge. In fact, the training of human resources has option characteristics (Berk & Kaše, 2010; Jacobs, 2007; Nembhard, Nembhard, & Qin, 2005). A knowledge option due to training is based on the possibility of companies using the additional productivity of their employees that results from the new knowledge and skill-sets that can be generated as a result of their investments in employee training.

There are, of course several important differences that must be taken into account between knowledge options and financial options, and also many real options on physical assets (Adner & Levinthal, 2004; Coff & Laverty, 2007).

A model is set out here that takes into account the above considerations.

3A model to explain the role of knowledge integration and knowledge options in a company's value creation by means of employee trainingThe starting point for our analysis is a simple microeconomic production model of a company. We assume that it has no production factors other than its own employees, and that it is in equilibrium. The net earnings of a company comprise the difference between the revenue from its operations and the salaries paid to its employees in a given period. Expression (1) shows this relationship.

where πt−2 is the net earnings of the company in t−2, μ the result of the activities of the company, Ei the labour costs to the company of employee i and n is the number of employees.

In the following period, t−1, the values of the variables are not modified, except that the firm invests in a training course for an employee, so that he or she acquires external knowledge with a view to improving his/her productivity and sharing his/her new knowledge with other employees, who can thus also improve their productivity. This investment is only made in one period and is irreversible, as shown by expression (2).

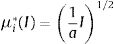

where I is the investment in an external training course.We define “training course” as a structured, planned action over a limited time, intended to acquire new knowledge from an external source. We thus assume that the greater the employee's initial productivity is the less additional effect the investment will have on the outcomes of training. Expression (3) describes by way of example the additional outcome of such an investment in employee training.

where a is the initial productivity and μi* is the result of the investment in training for employee i.We take the possibility of sharing knowledge acquired with other employees into account. The success of knowledge sharing is positively related to the degree to which the new knowledge can be combined with the knowledge of each of the other employees (Minbaeva, 2005) and is expressed by means of an integration factor gi (gi≥0).

Furthermore, the model includes a knowledge option Ci (Ci≥0), generated by the possible future acquisition and/or generation of new knowledge, as any investment in improving the knowledge stock of an employee in a company can positively influence its future (Berk & Kaše, 2010). We assume that investment in a training course has a decreasing marginal productivity on the option as per the example shown in expression (4).

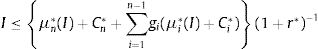

where Ci* is the value for the company of knowledge option Ci generated by investment I in training.Expression (5) combines these points and describes the result of the company in period t after having invested in a training course for employee n. Thus, this net result is the sum of the following elements: the result of the company's operations in the previous period, prior to the investment in training (μ); the sum of the results of the training course for employee n and for the other employees due to their receipt of the new knowledge acquired by employee n; the value of the knowledge options generated through this training course for employee n and for all the other employees of the company; and, with a negative sign, the labour costs of the employees for the company (∑i=1nEi).

where Ci*=Ci ln I→Ci=f(V,S,τ,σ,r,D) and gi is the Integration factor→gi=f(c,R,p,T,k).Assuming that gi≥0, and taking into account that Ci*≥0, a condition is that the discounted results of the training are greater than the investment made:

where r* is a risk adjusted discount rate.Since a knowledge option can be considered as American call option (Brealey, Myers, & Allen, 2017; Damodaran, 2018) its value depends on the following variables:

Value of the underlying asset (V) (+). The “underlying asset” can be any identifiable new knowledge, skill-set, competence, project, etc., that may be generated or started in the future due to the knowledge acquired via the current training of employee i. Accordingly, the value of the underlying asset can be interpreted as the expected effective value of the cash flows due to one or more of these future assets. Its value is positively related to the value of the option.

Exercise price (S) (−). The exercise price can be interpreted as the outlays that the firm will have to assume in the future to be able to “exercise” the knowledge option with respect to employee i. Those outlays may consist of additional training to develop existing knowledge held by employees, costs relating to R&D projects, etc. and negatively influence the value of the option.

Volatility (σ) (+). Volatility can be interpreted as the uncertainty associated with the value of the underlying asset. The value of the option increases when volatility increases, as do the possibilities of the value of the underlying asset being higher (Kulatilaka & Perotti, 1998).

Volatility is, in turn, a function of different variables: σ=f(s;l;d), where:

- (a)

The specificity of the acquired knowledge (s) (−). We assume that its impact is negative, as it reduces volatility, i.e. uncertainty with respect to the value of the underlying asset. This is because very specific knowledge has a very specific utility, while general knowledge can be used on many more occasions and therefore increases the variability of the future value of the underlying asset.

- (b)

The complexity of the production processes and markets (l) (+). Complex markets and processes tend to be knowledge-intensive. High knowledge intensity means that the outcomes and needs of the production processes of the firm are relatively more unpredictable. Thus, this variable positively influences volatility and, therefore, the value of the option.

- (c)

The dynamics of the environment (d) (+). The more dynamic the environment of the firm is, the more uncertainty it generates, but that higher uncertainty means that new business opportunities can be developed.

- (a)

Lifetime of the option (τ) (+). The lifetime of the option can be interpreted as the time interval in which the knowledge acquired by training can be used to generate or start the underlying asset. In this case, this period can be interpreted as the time remaining until the new knowledge acquired by the employees loses all its value. The value of the option increases with the lifetime of the option.

Risk-free interest rate (r) (+). As with financial options, we assume that the risk-free interest rate positively influences the value of the option.

Depreciation factor (D) (–). The depreciation factor reflects the dividends in the case of a financial option. It includes all the factors capable of reducing the value of the underlying asset over time. The devaluation of any knowledge over time likewise reduces the value of the option.

Another determinant variable of the model is the integration factor gi (gi≥0). This factor indicates the value of the point up to which the knowledge is shared successfully between one employee and another. Assume that gi, i.e. the value of g for employee i, depends on the following factors, which represent an aggregation of factors recognised in literature in regard to the integration and sharing of knowledge (Abu-Shanab, Haddad, & Knight, 2014; Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Laursen & Mahnke, 2001; Razmerita, Kirchner, & Nielsen, 2016; Yahya & Goh, 2002):

Organisational culture (c) (+).Bleicher (1986) asserts that an organisation is a culture. Consequently, an organisation can foster the internal adoption and sharing of knowledge by implementing an appropriate organisational culture based on its intra-organisational social capital (Al-Alawi, Al-Marzooqi, & Mohammed, 2007; Kathiravelu, Mansor, Ramayah, & Idris, 2014; Maurer, Bartsch, & Ebers, 2011; Poul, Khanlarzadeh, & Samiei, 2016; Rezaei et al., 2016). We assume that the more those processes are supported by the organisational culture, the greater the value of gi will be.

Knowledge transfer mechanisms and knowledge management routines (R) (+). Suitable knowledge transfer mechanisms and routines, defined as “[…] relatively simple decision rules and procedures […] used to guide actions” (Nelson & Winter, 1982, p. 14), may foster the internal adoption and sharing of knowledge by stabilising organisational behaviour. Their effectiveness is therefore assumed to be correlated positively with the value of gi.

Personal capabilities of employees (p) (+). This category includes all the factors that influence the ability of an employee to apply knowledge acquired and share it with others. The personal capabilities of each employee p are assumed to influence gi positively.

Technology infrastructure (T) (+). The technology infrastructure, particularly ICTs, can foster the flow of information within an organisation, thus facilitating the sharing of knowledge. So this factor also positively influences gi.

Knowledge compatibility (k) (+). Another aspect is the compatibility of the new knowledge acquired with the production factors and processes within an organisation. The more compatible the new knowledge is with the production processes, the greater the value of gi is.

A differentiating characteristic of knowledge as a production factor that should not be forgotten is that knowledge evolves with the transfer from the issuer to the recipient, i.e. the recipient combines the knowledge received with his/her own knowledge, thus creating new knowledge (Nonaka, 1991). Of course, the more specific the new knowledge obtained is, the fewer possibilities there are for its combination and, therefore, evolution. This possible evolution of knowledge turns it into a production factor with increasing returns to scale, at least to some extent. Consequently, the gi factor can even reach values above 1.

We now apply this model to four different hypothetical cases for discussion.

4Application to cases and discussionWe distinguish between the results that the model provides for training exclusively involving fully specific knowledge and those for training on totally general knowledge; we likewise assume fully heterogeneous production processes each employee performs a different process or totally homogenous ones within a firm. Naturally, these are extreme cases. In reality, knowledge and processes are found at an intermediate level. Nevertheless we believe that considering the extremes may be useful to gain a better understanding of the effects of the variables on the results of investment in training.

4.1Case I: a firm with totally heterogeneous production processes investing in fully specific knowledgeWe begin with the hypothetical case (Case I) of a firm with totally heterogeneous production processes that invests in a training course on fully specific knowledge. Thus, the specific knowledge acquired by employee n is not compatible with the processes performed by other employees and it cannot be combined with other types of knowledge. Therefore, knowledge option Cn has a value close to zero, as the volatility (σ) should be relatively low and the exercise price (S) is very high. Furthermore, due to the lack of compatibility of the knowledge acquired by employee n with the production processes executed by the other employees, the value of variable k is zero. Accordingly the integration factors gi also have values close to zero and there are either no knowledge options for other employees or they have much lower values. Expression (5) transforms into expression (6).

Expression (7) shows that in this case the effects on the earnings of the firm of a hypothetical investment in a training course depend fundamentally on the initial productivity of the employee, with an inverse effect (see e.g., Marquardt, Robelski, & Jenkins, 2011).

4.2Case II: a firm with totally homogeneous production processes investing in fully general knowledgeA similar case is that of a firm with homogeneous production processes that invests in a training course, also for employee n, but on general knowledge (Case II). In this case, the firm has totally homogeneous production processes, which means that the production processes to be performed by employee n are the same as those executed by each other employee in the firm. Therefore, the firm's competitiveness is based essentially on specific knowledge relating to processes executed by employees. Consequently, only a small part, if any, of the general knowledge acquired by training is compatible with and valuable to the production processes. As a result, the exercise price of the option becomes very high and the value of the option becomes very low. Furthermore, the high degree of incompatibility of the general knowledge acquired by training with the production process means that the integration factor is also low. If the firm provides training in knowledge not applicable to the production processes run by the employee(s) the training does not help to increase productivity beyond any possible improvement in employee n. Therefore, the result in this case can also be expressed by (6) and (7).

Case I+Case II. (where Ci≅0;gi≅0;I≤μn*(I)(1+r*))−1

4.3Case III: a firm with totally homogeneous production processes investing in fully specific knowledgeThe third case (Case III) corresponds to a situation where a firm with totally homogeneous production processes, as in Case II, invests in a training course on specific knowledge for employee n. Unlike the previous cases, we assume a high compatibility k of the new knowledge obtained and the processes executed by the remaining employees. If we also assume, reasonably, that the other variables that influence gi have positive values, the integration factors become positive. Yet the knowledge is specific, so the value of the knowledge option will be close to zero. Expression (5) transforms into expression (8).

Case III. (where Ci≅0;gi>0;I≤[μn*(I)+∑i=1n−1μi*(I)](1+r*)−1)

We now add the possibility of opportunistic behaviour by the employee(s) after training. Opportunistic behaviour by an employee can be displayed by means of intention to renegotiate his/her salary or to leave the company in order to get another job. In Case I and Case III the specific nature of the knowledge means that his/her external employability does not increase due to the new knowledge acquired. However in Case III the specific knowledge may have substantial value for the firm, so the best risk-management attitude would be to train several people simultaneously, while taking into account that spending on any individual employee may not exceed the additional productivity that he/she gains through training μi*(I).Taking the foregoing into account, considering expression (9) and also those factors other than k that influence gi – i.e. organisational culture, knowledge transfer mechanisms and knowledge management routines, employee personal capabilities and technology infrastructure, we put forward the following Proposition 1:Proposition 1 In companies with homogeneous production processes, investment in training employees in specific knowledge will provide better results if: The organisational culture of the firm fosters the sharing of knowledge. The company has developed an effective set of formal mechanisms and routines for internal knowledge adopting and sharing. Employees are better able and willing to absorb and share knowledge. There is greater development of technological knowledge adoption and sharing tools. The relative proportion of the workforce trained simultaneously in relevant knowledge is higher. The share of knowledge linked to the production processes is higher.

Finally, Case IV considers a firm with heterogeneous production processes that invests in a training course for employee n in order to equip him/her with general knowledge.

Thus, the availability of certain general knowledge is not only a condition for executing a certain work process (for example, a commercial agent who has to work a new market must learn an appropriate language to be able to communicate with the agents in that market), but also forms a basis for acquiring new knowledge in the future (for example, after the new language has been learned new business opportunities may be discovered that only exist in this market and which had not previously been imagined). Consequently, the exercise price (S) has a low value. If we also assume that general knowledge depreciates more slowly, the value of the depreciation factor D is also low. Furthermore the volatility (σ) is expected to be high. Therefore, knowledge options Ci have comparatively high values. As in Case III, we assume positive values for the integration factors gi. Thus, expression (10), corresponding to this case, is identical to (5).

Case IV. (where Ci>0;gi>0;I≤{μn*(I)+Cn*+∑i=1n−1gi(μi*(I)+Ci*)}(1+r*)−1)

What happens with opportunistic behaviour by an employee? In Case IV, unlike the cases I, II and III, the results depend positively on the knowledge options Ci. But despite the great benefits that investing in external knowledge may provide for the firm, the employability of the person who receives that training will also increase given the existence of markets for his/her general knowledge gained along with his/her power to renegotiate his/her salary. Thus, the firm may lose both the increase in productivity and the value of the knowledge option. Given the difficulty of determining the value of Cn and the nature of general knowledge, which not only needs a comparatively long time to acquire it but also requires comparatively strong efforts to combine it with existing knowledge in order to exploit it, we need alternative risk management instruments: selecting the most suitable employees to receive the knowledge becomes decisive, as does binding them to the company by means of pecuniary or non-pecuniary incentives.Considering the above procedure, and taking expression (11) into account, the factors that influence gi and also, as the main determinant of Ci, the factors other than the specificity of knowledge that influence volatility (σ) complexity of the production processes, complexity of markets and dynamics of the environment we suggest Proposition 2:Proposition 2 In companies with heterogeneous production processes, investment in training of employees in general knowledge will provide better results if: The organisational culture of the firm fosters the sharing of knowledge. The company has developed an effective set of formal mechanisms and routines for internal knowledge adopting and sharing. Employees are better able and willing to absorb and share knowledge. There is greater development of technological knowledge adoption and sharing tools. Production processes are more complex. The markets in which the firm operates are more complex. The environment is more dynamic. There is an incentive system that associates incentives with training. The share of knowledge that is compatible with the production processes is higher.

This paper demonstrates that it is possible to develop a model that integrates knowledge management and real options approaches to explain the environmental conditions and factors for successful employee training. These conditions and factors are associated with the type of production processes at companies homogeneous or heterogeneous and with the type of knowledge specific or general obtained by means of training. Along with the immediate effect of training on the knowledge of the employee, and therefore on his/her productivity, the effect of the integration of the new knowledge held by the employee with that of other employees ought to be considered, as it gives reason for the values of the knowledge options generated by these processes. In this way, the proposed model conducts to an explanation about the results of several empirical studies in that the contribution of training to the results of companies is greater than expected under classic human capital models. Thus, we conclude that Knowledge Management and Real Option approaches supplement each other.

Our model identifies factors for the successful adoption and sharing of knowledge. It shows that different kinds of knowledge acquired by training (specific or general) require different management strategies to secure investments in training, and also provides decision criteria on whether an investment in knowledge acquisition is helpful and how to improve its results.

Thus, several managerial implications can be deduced from Proposition 1 (Section 4.3) and Proposition 2 (Section 4.4) such as the importance to be aware of the production processes and the nature of the knowledge to be acquired as long as these two dimensions influence in particular in order to maximize training measures out. In any case, managers are encouraged to take efforts to implement an appropriate knowledge adoption and sharing culture, and technology infrastructure within their companies since these actions support the exploitation of training measures on any combination of production process and type of knowledge. Furthermore, the handling of differences in the mentioned dimensions becomes emphasised to be able to comply with the challenges of opportunistic behaviour on the part of employees and of unforeseen business opportunities. Specifically, as indicated by Proposition 2, if a company has heterogeneous production processes and the conditions laid down in this proposition are met, it is expected to be able to exploit its knowledge options comparatively better resulting in higher returns of the investments in training measures with the aim to acquire general knowledge.

The paper has its limitations. The factors on which the success of training depends are likely to be more diverse and interrelated in more complex ways than reflected in the model presented here. It may be necessary to develop more complex models that enable broader sets of factors and links between them to be identified.

Secondly, this paper presents a model that uses mathematical equations from which a series of propositions have been deduced. Using appropriate measurement scales, these can be transformed into empirically testable hypotheses. Obviously, the effective relevance of the factors identified in this paper can only be verified by means of empirical analysis. Finally, most of the factors presented are not directly observable and prior work is needed to construct measurement scales that enable them to be satisfactorily identified.