Crowdfunding is an Internet-based fundraising method that relies on contributions from a large crowd of investors to fund innovative and risky projects. The aim of this paper is to analyse which combinations of signals commonly studied for crowdfunding success lead to overfunding. Based on the information asymmetries between fund-seeking entrepreneurs and the crowd, this paper draws on signalling theory to explore the elements of campaign design that contribute to overfunding (i.e. raising at least 10 % above the funding target). The paper focuses on the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation, pitch video length, budget explanation length, number of images, project abstract length, and number of updates by the entrepreneur. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is performed using publicly available data sourced from 257 socially oriented projects from a reward-based crowdfunding platform. The results show the importance for entrepreneurs of using images and constantly communicating with the crowd. The results also reveal a series of configurations of design features that result in overfunding. These findings have practical implications for the design of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns and contribute to a better understanding of how economic agents interact within crowdfunding.

Born out of the credit shortage following the 2008 financial crisis (Pichler & Tezza, 2016), crowdfunding soon emerged as a financing method that democratises innovation and access to capital, especially for early-stage startups. As Mollick & Robb (2016) noted, crowdfunding allows the creation of a global, agile, and dynamic funding market that interconnects geographically distant funders and entrepreneurs thanks to its use of the Internet and social media, while also allowing the crowd to act as a feedback mechanism to inform on market preferences that can aid in the innovation generation process.

Despite many studies have addressed the dynamics of the crowdfunding process (e.g. Belleflamme, Lambert, & Schwienbacher, 2019; Kuppuswamy & Bayus, 2018; Mollick, 2014), campaign design factors that contribute to crowdfunding optimal performance still require thorough analysis, especially from a configurational perspective, given the existing variety of crowdfunding platforms settings and rewards dynamics as well as the evolving way in which the crowd interacts in online environments.

The dynamics of engaging new funders has been widely studied using signalling theory, which was initially devised by Spence (1973) in the field of contract theory. For example, Davies & Giovannetti (2018) analysed a sample of 10,000 crowdfunding successes and failures on the Kickstarter platform, concluding that on-platform information contributes to overcoming moral hazard and adverse selection, signalling further quality. In turn, Huang et al. (2022) conducted qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), employing the signalling theory model to address the interaction of different cues, including entrepreneur credibility and project quality, using data sourced from Kickstarter and Indiegogo. The results suggest two configurational patterns: one based only on entrepreneur credibility when seeking funding and the other combining this form of credibility with project quality.

Similarly, De Crescenzo et al. (2022) examined the role of content communication (namely text, visual content and updates) and third-party endorsement as information asymmetry mitigators in reward-based crowdfunding campaigns using a configurational approach. However, recent papers have paid attention to the understudied phenomenon of overfunding (i.e. raising funds above the funding target) in reward-based (Pinkow, 2023) and equity crowdfunding (Sendra-Pons et al., 2024; Wasti & Ahmed, 2023). This has highlighted a research gap that this paper aims to address.

The rationale for studying the drivers of success of a crowdfunding campaign (or overfunding) through the lens of signalling theory rests largely on the information asymmetries that exist between entrepreneurs as fund seekers and prospective project backers, who can only rely on the information provided by entrepreneurs to make funding allocation decisions (Courtney et al., 2017). Accordingly, whereas entrepreneurs have privileged information about their projects and hence a better understanding of their chances of success, backers confronted with a catalogue of projects soliciting investment must infer project quality from the limited available information (Comeig et al., 2020; Miglo, 2021).

This paper analyses the combinations of signals within reward-based crowdfunding campaigns that result in overfunding (operationalised as exceeding the funding goal by at least 10 %): the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation [IDEN], pitch video length [LVIDE], budget explanation length [LBUDG], number of images [NIMAG], project abstract length [LEXP], and number of updates by the entrepreneur [NUPD]. The analysis is based on qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). The sample consists of data from 257 socially oriented projects launched on Goteo.org, a reward-based crowdfunding platform.

Ultimately, the goal of this study is to shed light on the phenomenon of overfunding, which has been relatively understudied in comparison to the extensive research conducted on crowdfunding success. It contributes to developing the theories of asymmetric information and signalling and provides a series of practical insights for fund-seeking entrepreneurs, potential backers, and reward-based crowdfunding platforms as regards the information disclosure strategies that lead to overfunding. The methodological approach of this study captures the underlying equifinality and multifinality of overfunding drivers and provides fresh insights into the combinations of information elements that are conducive to particularly high levels of fundraising. In short, the study improves the understanding of an increasingly critical phenomenon for entrepreneurs from both a theoretical and a practical perspective.

In the next section, a theoretical framework is built around the dynamics of crowdfunding, its risks, information asymmetries, the role of signalling, incentive misalignment, and information disclosure. Next, the data and method are described. Following the method section, the results are presented. Then, a discussion is developed, paying special attention to managerial implications for entrepreneurs. Lastly, the conclusions, limitations and ideas for further research are presented.

2Theoretical framework2.1Crowdfunding as an alternative to traditional funding channels: dynamics and risksAccording to Belleflamme et al. (2015), there are two major crowdfunding business models (see Table 1). Investment-based crowdfunding includes equity-based, royalty-based, and lending-based crowdfunding, in which every backer receives financial compensation (Gierczak et al., 2016). Non-financial-based crowdfunding, in contrast, includes reward-based and donation-based crowdfunding, which is characterised by compensation in the form of products (Steigenberger, 2017) or personal satisfaction for supporting a cause (Bagheri et al., 2019).

Major crowdfunding business models.

| Business model | Reward | |

|---|---|---|

| Investment-based crowdfunding models | Equity-based | Shares |

| Royalty-based | Royalties | |

| Lending-based | Interest | |

| Non-financial-based crowdfunding models | Reward-based | Sample product |

| Donation-based | Personal satisfaction |

Source: Adapted from Belleflamme et al. (2015). Note: ‘Non-financial-based crowdfunding models’ is a term coined by the authors of the present paper as an extension of the initial characterisation.

In terms of crowdfunding dynamics, there is an important distinction between the behaviour of fund-seeking entrepreneurs and that of prospective backers. Initially, entrepreneurs register on a crowdfunding platform and decide on the type of reward they want to offer the crowd. At this stage, they provide the information they deem appropriate (e.g. images, minimum project budget, description, videos, and expert opinions) to justify their ability to complete the project. They thus try to mitigate information asymmetries. Then, the crowd plays its role by funding the project before the last day of the campaign.

In all-or-nothing campaigns, investment is not possible after the last day of the campaign. Moreover, any funds that have been pledged are returned to the crowd if the funding goal is not met, incurring an opportunity cost (Cumming et al., 2020). During the fundraising process, entrepreneurs can take actions to encourage investment. For example, they can send messages to prospective backers via their campaign page (Dorfleitner et al., 2018). Upon successful completion of the funding process, entrepreneurs implement the project, rewarding the crowd in a timely fashion as previously agreed with products, interest on investment, shares, or explicit recognition as project funders (Kuppuswamy & Bayus, 2018).

As explained by Meyskens & Bird (2015), the process essentially has five phases: (i) an entrepreneur designs a campaign and (ii) chooses a platform; (iii) the crowd funds the project and interacts with the entrepreneur; (iv) the entrepreneur implements the project and (v) distributes the rewards, if any, to the backers. Phase (iii) has three subphases: ‘friend funding’, where contributions come mainly from the entrepreneur's immediate circle, ‘getting crowded’, where the herding or cascade process begins to grow, providing a reinforcing cycle of investments, and the ‘race to the goal’, in which momentum builds and investments accelerate until the goal is achieved (Kim et al., 2020). This study aims to shed light on the campaign design phase, a crucial juncture in the subsequent fundraising process. The campaign design phase influences all other phases of the fundraising process (i.e. ‘friend funding’, ‘getting crowded’, and ‘race to the goal’). An optimal design is especially relevant in the early stages of the campaign, when there are few backers, because information asymmetries are at their greatest.

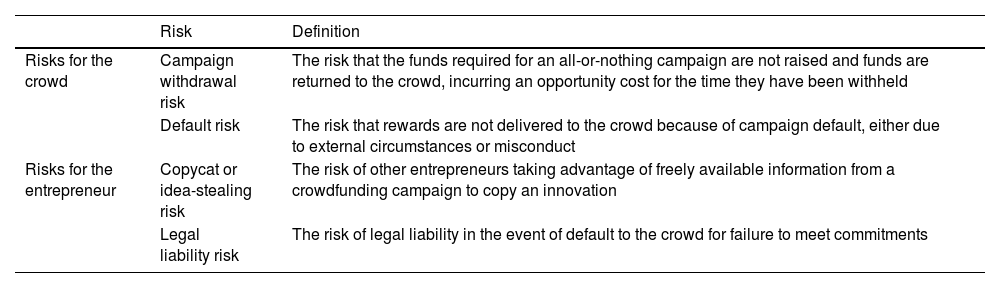

Perhaps surprisingly, crowdfunding entails a series of risks summarised in Table 2 that are compounded by information asymmetries between entrepreneurs and potential backers. On the funder side, one risk is that the campaign will not achieve its funding goal. In an all-or-nothing campaign, as advanced earlier, this failure to achieve the funding goal would mean that funds would be returned to the crowd, thus incurring an opportunity cost (Comeig et al., 2020). There is also the risk of entrepreneur default as a result of external circumstances that cause the venture to collapse once the crowd's funds have been employed or because of intentional misconduct (Cumming et al., 2023).

Main risks for entrepreneurs and the crowd.

| Risk | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Risks for the crowd | Campaign withdrawal risk | The risk that the funds required for an all-or-nothing campaign are not raised and funds are returned to the crowd, incurring an opportunity cost for the time they have been withheld |

| Default risk | The risk that rewards are not delivered to the crowd because of campaign default, either due to external circumstances or misconduct | |

| Risks for the entrepreneur | Copycat or idea-stealing risk | The risk of other entrepreneurs taking advantage of freely available information from a crowdfunding campaign to copy an innovation |

| Legal liability risk | The risk of legal liability in the event of default to the crowd for failure to meet commitments |

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Comeig et al. (2020), Cowden & Young (2020), and Cumming et al. (2023).

On the entrepreneur side, although crowd-based systems favour innovation by providing the entrepreneur with real market feedback when designing, producing, and marketing a product or service, there is a risk of imitation by third parties. This risk increases if the goods or services are not subject to intellectual property protection (Cowden & Young, 2020). Another risk, which is closely related to the risk of default, is the legal liability that entrepreneurs may have to the crowd for non-compliance with their commitments.

This paper focuses on the elements of crowdfunding campaign design that help mitigate information asymmetries between entrepreneurs and the crowd. These elements are described in the next section. Campaign withdrawal risk can thus be reduced by activating a reinforcing cycle of capital raising that results in high fundraising rates. By revealing configurational strategies that increase the crowd's engagement in campaign fundraising, this research has practical implications for promoting overfunding.

2.2Asymmetric information in the crowd-based funding model: the role of signallingDrawing on the arguments of Akerlof (1970) in ‘Market for “Lemons”’, any entrepreneur possesses, ex-ante, the most accurate information available about the unbiased likelihood of success of the entrepreneur's campaign. In contrast, the crowd, under a veil of ignorance, can only infer the assumed quality of the project, and thus the likelihood that it will be financed, based on the limited information offered by the entrepreneur. The principal-agent relationship occurs both ex-ante and ex-post the beginning of the funding transaction between the crowd and the entrepreneur. This paper focuses on the ex-ante stage by exploring which strategies minimise the information asymmetries between principal and agent prior to the transaction and thus support completion of the transaction.

Principal-agent theory refers to the relationship between two parties: the principal and the agent. The principal delegates work to the agent according to pre-established conditions (Chaney, 2019; Eisenhardt, 1989). Two information problems occur under this theory. The first is a pre-contractual or ex-ante problem, whereby adverse selection can occur when the agent has information about the quality of the project that the principal lacks. The second is a post-contractual or ex-post problem, whereby moral hazard occurs when the principal selects an agent that does not deliver what was promised (Jensen & Meckling, 1976, as cited in Miglo & Miglo, 2019; Rothschild & Stiglitz, 1978).

Signalling theory was introduced by Spence (1973). It was initially grounded in the job market, where hiring was likened to buying a lottery ticket. In this context, Spence (1973) suggested the importance of signals in decision-making processes under uncertainty. Since then, this theory has been a fundamental part of academic research in a variety of fields, including anthropology, management, and psychology. It has also been extensively employed as a theoretical model in crowdfunding research (e.g. Ahlers et al., 2015; De Crescenzo, Monfort et al., 2022; Vismara, 2018). As accurately portrayed by Courtney et al. (2017), because backers in entrepreneurial crowd-based fundraising have incomplete and imperfect information, they are exposed to the economic risk of investing in a lemon, in terms of Akerlof's original theory. Therefore, entrepreneurs must provide credible information to the less-informed party (i.e. the crowd of backers) to aid with the transaction's completion.

Of all the theories used to study situations of incomplete and asymmetrically distributed information, signalling theory (Spence, 1973; 2002) is perhaps the most widely used in the context of entrepreneurial finance and, specifically, crowdfunding. As explained by Vismara (2018), crowdfunders are faced with high information-processing costs that they have neither the ability nor the incentive to cope with, either because they invest too little, making the investment economically inefficient, or because they are unable to decide who should pay for the due diligence and thus suffer free riding if they invest a larger amount. This entire situation may result in a reluctance to invest in crowdfunding projects, which ‘could eventually produce an Akerlof-type market failure, resulting in vanishing markets because the only equilibrium price would be zero’ (Vismara, 2018, p. 30). Furthermore, as an extension to classical signalling theory, Steigenberger and Wilhelm (2018) point out that potential backers, far from processing signals in isolation, see bundles of signals as a complement to substantive signals. This emphasises the importance of the configurational approach (i.e. studying combinations of signals) considered in this research. In addition to signalling theory, information disclosure in a crowdfunding campaign can be viewed from the perspective of organizational legitimacy, i.e. ‘a favorable judgment on the acceptability of an organization's actions, based on their utility, justice, and appropriateness’ (Díez-Martín et al., 2021, p. 3). In this sense, Chen (2023) argues that in crowdfunding environments, moral legitimacy as well as pragmatic, associational, and consequential legitimacy may play a relevant role in driving pledge amount, success, and number of backers, although the results are mixed. Additionally, data from Frydrych et al. (2014) showed that project characteristics are associated to such legitimacy and success in reward-based crowdfunding.

2.3Incentive misalignment and information disclosureReward-based crowdfunding is a sort of Internet-based fundraising in which an entrepreneur usually compensates the crowd by providing a sample of the final product once it has been manufactured (Steigenberger, 2017).

According to Wessel et al. (2021), four strategies can be implemented when there is incentive misalignment: (i) a contracting strategy, in which a reward scheme is implemented; (ii) a voluntary disclosure strategy, in which trust is generated through voluntary disclosure of information; (iii) a feedback strategy, in which an iterative process of communication between principal and agent occurs in bilateral negotiation; and (iv) a deferred compensation strategy, in which an effortful attitude of the agent is encouraged, thereby moving away from opportunism by sharing costs or benefits.

Arguably, campaign design strategies aimed at favouring overfunding would be directly aligned with Wessel et al.’s (2021) strategies (ii) and (iii): a voluntary disclosure of textual and visual information and feedback through updates, respectively. Specifically, these design strategies would seek to build trust by displaying detailed information about the campaign and establishing an effective, fast, and agile communication channel in which uncertainty is reduced as the entrepreneur builds a sense of trust and reassurance with the crowd. The design elements of a campaign considered in this study are the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation [IDEN], pitch video length [LVIDE], budget explanation length [LBUDG], number of images [NIMAG], project abstract length [LEXP], and number of updates by the entrepreneur [NUPD].

Because of the uncertainty that dominates reward-based crowdfunding campaigns, information disclosure strategies by entrepreneurs to prospective backers are powerful marketing tools to build trust (Baah-Peprah & Shneor, 2022). Accordingly, a reward-based crowdfunding campaign should be seen not only as a mere fundraising transaction but also as an opportunity to increase product visibility and assess whether there is a market for that product (Giones & Brem, 2019). The relevance of awareness of what information disclosure strategies result in overfunding stems not only from their potential for gathering large amounts of money but also from their potential value as marketing tools to position a product in the marketplace and attract early adopters (Allegreni, 2017).

The following subsections present theoretical background on the influence of the information elements considered (IDEN, LVIDE, LBUDG, NIMAG, LEXP, and NUPD) on the outcome of interest (i.e. overfunding or OVERF). These conditions are then arranged into configurations (logically feasible combinations of conditions) based on the results of the QCA.

2.3.1The entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation [IDEN]The entrepreneur's identity as either an individual or a corporation is included in the model to explore whether the fact that the fund seeker is a human or a company influences the achievement of campaign overfunding. While other papers, for instance, have explored whether the crowdfunding projects are led by an individual or a team (Frydrych et al., 2014), current research focuses on whether the project is led by an individual or corporate entrepreneur1. From a legal point of view, the fact that the entrepreneur is a human and not a corporate entity entails greater individual liabilities than those that could arise from criminal conduct by a limited liability company (Khandekar & Young, 1985). Beyond the tax implications or the costs associated with business creation, the fact that an entrepreneur is not incorporated as a company with limited liability may demonstrate her or his degree of confidence in the success of the entrepreneurial project. On the other hand, however, it signals a lower level of formalisation or maturity of the project, which can translate into a higher probability of failure. From the point of view of the emotional bonds that potential backers can forge with entrepreneurs, there is evidence that individual entrepreneurs, as human entities, are capable of fostering trust among potential backers (Boeuf et al., 2014) as well as that brands can also generate attachment through trust, familiarity and experience (Chinomona & Maziriri, 2017). Given this mixed evidence, one might argue that whether the entrepreneur's identity matters for overfunding might depend on the interplay of the different information elements that make up the information disclosure process.

2.3.2Pitch video length [LVIDE]Courtney et al. (2017) have found that using videos and images in a crowdfunding campaign can mitigate the problems arising from information asymmetries in such digital financial environments. As noted by Yang et al. (2020), a number of studies have indicated that using rich multimedia for information disclosure can signal fund seeker credibility (Calic & Mosakowski, 2016; Courtney et al., 2017; Parhankangas & Ehrlich, 2014). Indeed, the use of videos in entrepreneurial crowdfunding campaigns has been found to increasingly play a role in raising psychological capital (Anglin et al., 2018). Videos that are especially enthusiastic raise the most investment (Li et al., 2017), whereas those that narrate real testimonials are preferred (Appiah, 2006; Yang et al., 2020). Unsurprisingly, Bi et al. (2017) concluded that videos can make backers infer higher project quality. In line with this research, Wheat et al. (2013) identified the use of a video as the most relevant resource in attracting potential backers, not only because it demonstrates a minimum level of preparation when launching the fundraising campaign, but also because it allows to introduce both the project and team of entrepreneurs leading it.

However, as Sundar (2000) warn, excessive video content in a campaign might hinder cognition, losing the attention of prospective backers. This favours the use of informative and concise videos, thus maximising their signalling power. In addition, a recent study by Kolbe et al. (2022) showed that the use of video pitches in crowdfunding campaigns resulted in higher amounts of funds raised in crowdfunding. Ultimately, videos mitigate existing information asymmetries by providing relevant information to potential backers and signalling project quality (Honisch et al., 2019). This is consistent with Blanchard et al. (2023), who, by revising the literature, emphasise the role of visual content (and specifically the number of images and videos) as a cornerstone in the study of crowdfunding success predictors.

2.3.3Budget explanation length [LBUDG]Financial and economic metrics regarding an entrepreneurial venture seeking funding offer pivotal information to decide where to invest. As noticed by Hobbs et al. (2016), it is essential to provide detailed information on how the funds raised will be used. Given that crowdfunding is a highly asymmetric environment, it is vital for potential backers to identify those signals that allow them to infer the entrepreneurs’ commitment to reward them as previously agreed. The budget explanation, as a financial literacy signalling device, allows the crowd of potential backers to infer such financial commitment. According to Mason & Stark (2004), the economic-financial rationale of a business proposal, together with other aspects such as the competitive environment, is fundamental in an investment decision-making process. In fact, financial aspects are of importance whether for bankers, equity investors, venture capital fund managers and business angels, although the latter give more importance to the specific knowledge they may have on the industry or market involved. This only reinforces the ‘“hard evidence”-oriented, “substance”-based’ nature of the decision-making process by investors (Clark, 2008).

However, it is important to consider the non-professional nature of potential backers in some types of crowdfunding, such as reward-based crowdfunding, that requires financial information to be reported in a more accessible jargon (Leboeuf & Schwienbacher, 2018). In any case, financial projections, including budgeting or financial forecasts, help to better understand the entrepreneurial project's potential risks, allowing the crowd of investors to form better expectations about its attractiveness (Ahlers et al., 2015). While financial disclosure is essential in equity-based crowdfunding due to the need to report accounting metrics that provide insight into key aspects of a company's financial management (Axelton & Chandna, 2023), it may be less important in crowdfunding environments that are plagued by non-specialist investors. However, this does not mean that there may not be a signalling effect if the information is intended for non-professional backers who may be deterred by its complexity.

2.3.4Number of images [NIMAG]Like videos, images are another type of multimedia content that have been found to be crucial for campaign success. A higher number of images has been linked to more funding (Chan & Park, 2015) by mitigating information asymmetries (Courtney et al., 2017). More specifically, image attributes can influence emotions, with a resulting relationship with pledge intention. In Chen et al. (2023), images are evaluated from the perspective of the first impression of potential backers on the reward-based crowdfunding platform Indiegogo, and the number of human faces in images is found to incentivise fundraising. On the other hand, images make it possible to overcome the limitations of written information, with which it would be highly complex to show prototypes or designs, and to offer much more easily interpretable information (Koch & Siering, 2015). In addition, images can convey moods as well as a certain wealth or poverty status which could influence perceived borrower trustworthiness and, ultimately, the fundraising campaign success (see Anderson & Saxton, 2016).

In the words of Xiao et al. (2021, p. 3216), ‘more picture postings may signal the creator's diligence and preparation (…) enhancing creator's perceived credibility’. Indeed, preparedness and commitment can in turn give the impression of a better qualified and more determined entrepreneur, gathering more contributions (Colombo, 2021). However, when considering the interaction between different types of information, Yang et al. (2020) found that the positive influence of text length on fundraising success might decrease when videos and images become redundant. Drawing on cognitive load theory, they suggest the existence of an ‘overshadowing effect’ by which ‘redundant media can obscure the effects of other media in working memory’ (Yang et al., 2020, p. 13). However, QCA allows to observe combinations of conditions that result in a given outcome so that the effect of images will be examined in different scenarios together with other information elements. Ultimately, the effect of images on crowdfunding performance is far from conclusive, with recent papers even pointing out a significant negative effect on crowdfunding performance (Elrashidy et al., 2024).

2.3.5Project abstract length [LEXP]In online financial environments where information asymmetries are even more pronounced, the project explanation is essential. When an entrepreneur joins a crowdfunding platform, regardless of its nature, s/he is required to provide basic written information to communicate what her/his entrepreneurial project is about (Xiao et al., 2021). Based on Zhou et al. (2018), it can be assumed that a more detailed explanatory text means greater success in terms of reducing information asymmetries and increasing investment. When comparing the signalling capacity of videos with that of textual information, Lagazio & Querci (2018), making use of narrative theory, found that texts of a descriptive nature are even more persuasive than videos. Additionally, as more textual information is provided, these texts are perceived as more helpful (Mudambi & Schuff, 2010). Length, a recurring measure in crowdfunding research (Koch & Siering, 2019), offers a proxy for quality of information. Moreover, Adamska-Mieruszewska et al. (2021) find that text length and its readability significantly affect crowdfunding success and argue that longer texts are able to develop a greater number of arguments in support of the entrepreneurial venture, favouring persuasion.

Further, Moy et al. (2018), after studying a reward-based crowdfunding platform, reported an inverted U-shape relationship between text length and campaign success meaning that there is an optimal text length that translates into higher quality signalling, smaller information asymmetries and a greater chance of success. Recent findings by Gallucci et al. (2023) for equity crowdfunding also show that qualitative business information (e.g. about the project's business model and competitive strategy) is related to success in an inverted U-shaped manner. In an alternative approach, De Crescenzo, Bonfanti et al. (2022) analysed crowdfunding narratives thematically and lexically, identifying as strategic the information on the entrepreneurial project and its characteristics, along with the skills, competencies, and work dynamics of the team members responsible for the project.

2.3.6Number of updates by the entrepreneur [NUPD]In any business transaction, a continuous communication between parties is crucial, mainly for generating confidence. Updates provided by entrepreneurs to the crowd are a form of one-sided communication that could signal value to the crowd by providing additional information beyond what is available on the crowdfunding website (Block et al., 2018). This is also clear from the study by Xu et al. (2014), which not only asserts the unequivocal role of updates by entrepreneurs in leading to the success of the fundraising campaign, but also concludes that the interaction between entrepreneurs and potential backers is even more relevant than the explanation of the project itself. In the same direction, Mejia et al. (2019) also report a correlation between campaign updates and backer contributions.

This is also mentioned by Xiao et al. (2021) who, after concluding that a large number of updates are effective in getting more backers to fund, warn that the information presented in these updates must add to the information already available to these backers. It should be noted that the specific sequence through which the updates would lead to a better fundraising performance involves generating higher levels of attention towards the campaign, namely more visits from potential backers, and leveraging this increased visibility to create enthusiasm around the entrepreneurial idea to be funded (Kuppuswamy & Bayus, 2018). Updates are also more likely to occur when there is strong competition (Dorfleitner et al., 2018) since campaign information normally remains static while updates can be used by mutually exclusive competing campaigns to try to convince potential backers towards one of them. Ultimately, as De Larrea et al. (2019) concluded, success can be enhanced through frequent communication in the form of timely updates. Chen's (2023) results also suggest that a higher number of updates is associated with higher funding, as entrepreneurs who update potential backers on the progress of the campaign help to build consequential legitimacy.

Based on the previous theoretical framework rooted in signalling theory and the impact of the various information elements included in the analysis, the study's proposition is defined as follows.

Proposition: Multiple alternative information disclosure strategies that combine the signals used in the study (the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation, pitch video length, budget explanation length, number of images, project abstract length, and number of updates by the entrepreneur) are conducive to the overfunding phenomenon in reward-based crowdfunding.

3Data and methodThe data for this study were hand-collected from the Goteo.org website. The data covered 257 socially oriented projects for which data were publicly available. This reward-based crowdfunding platform2 was chosen because of its strong social facet and large amount of fundraising, which, at the time of writing, amounted to €16.356.496, according to the statistics reported by Goteo.org. Their social character is reflected in the fact that the projects are oriented towards the achievement of certain sustainable development goals. For each project, data were gathered on a number of design factors, namely the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation [IDEN], pitch video length [LVIDE], budget explanation length [LBUDG], number of images [NIMAG], project abstract length [LEXP], and number of updates by the entrepreneur [NUPD]. These design factors were then employed as conditions in the subsequent analyses. The outcome in the analysis was campaign overfunding [OVERF]. For this dichotomous condition, a value of 1 denoted that the campaign achieved funding at least 10 % above target (Sendra-Pons et al., 2024), and 0 indicated that it failed to do so. Table 3 shows the outcome and conditions used in the study, also denoting whether they were crisp (dichotomous) or fuzzy (continuous). The LVIDE, LBUDG, NIMAG and LEXP conditions follow the operationalisation procedure described in Geiger and Moore (2022) for text and images (Kim et al., 2016; Tafesse, 2021) while extending the operationalisation of videos to its length, measured in seconds, rather than just the number of videos (Bi et al., 2017).

Outcome and conditions used in the study.

| Type | Acronym | Definition | Codification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | OVERF | Project raising at least 10 % above target funding (overfunding = 1, otherwise = 0) | Crisp value |

| Condition | IDEN | Entrepreneur's identity as individual (1) or corporation (0) | Crisp value |

| Condition | LVIDE | Pitch video length (seconds) | Fuzzy value |

| Condition | LBUDG | Budget explanation length (words) | Fuzzy value |

| Condition | NIMAG | Number of images in the project description | Fuzzy value |

| Condition | LEXP | Project abstract length (words) | Fuzzy value |

| Condition | NUPD | Number of updates by entrepreneur | Fuzzy value |

Note: Crisp values refer to dichotomous data (0, 1), whereas fuzzy values refer to continuous data.

Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) was used for the study. This person-centred approach to management scholarship can reveal configurations of conditions leading to a certain outcome (Rey-Martí et al., 2022). Rather than establishing one-directional relationships between a single variable and a given outcome, fsQCA examines combinations of conditions (i.e. configurational paths). The advantage is that this approach can get closer to reality. FsQCA is built around the principle of equifinality, whereby an outcome can be achieved through different combinations of causally heterogeneous conditions (Ragin, 2008). It has been used extensively in organisational research (Fiss, 2011), including the study of crowdfunding as a fundraising method (e.g. De Crescenzo, Monfort et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Ribeiro-Navarrete et al., 2021).

Data calibration was carried out using fsQCA software to establish the three anchors associated with this method: full membership, maximum ambiguity, and full non-membership (Woodside et al., 2015). It must determine when a case has full set membership, full set non-membership, and ambiguity in set membership (Ragin, 2008). To calibrate conditions based on fuzzy values (LVIDE, LBUDG, NIMAG, LEXP and NUPD), the breakpoints for full membership, the cross over point and full non-membership are set at 20 % above mean, mean, and 50 % below mean, respectively (Berné-Martínez et al., 2021). From the aforementioned theoretical foundation, the model to be tested using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is defined as follows:

OVERF refers to overfunding (i.e. achieving funding at least 10 % above target), and IDEN,LVIDE,LBUDG,NIMAG,LEXP, and NUPD are conditions capturing crowdfunding design elements.4ResultsThe results reflect the analysis of necessary conditions, as well as the parsimonious solution of configurations of conditions that result in the outcome (i.e. overfunding).

4.1Analysis of necessary conditionsFirst, an analysis of the necessary conditions for overfunding was performed (see Table 4). Necessary conditions are those that are always present when the outcome occurs. According to Schneider and Wagemann (2012), for a condition to be necessary, consistency must exceed 0.9. No condition reached or exceeded a consistency of 0.9, so no condition was considered necessary. However, the ones that came closest to this value were ∼IDEN (0.762712) and ∼LBUDG (0.617427).

Analysis of necessary conditions.

| Condition | Outcome: OVERF | |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | |

| IDEN | 0.218447 | 0.762712 |

| ∼IDEN | 0.762712 | 0.817259 |

| LVIDE | 0.454660 | 0.815143 |

| ∼LVIDE | 0.545340 | 0.796173 |

| LBUDG | 0.382573 | 0.802301 |

| ∼LBUDG | 0.617427 | 0.806174 |

| NIMAG | 0.436748 | 0.804237 |

| ∼NIMAG | 0.563252 | 0.805037 |

| LEXP | 0.435777 | 0.787663 |

| ∼LEXP | 0.564223 | 0.818348 |

| NUPD | 0.451456 | 0.857143 |

| ∼NUPD | 0.548544 | 0.766102 |

Note: The symbol ‘∼’ refers to the negation of a condition.

The three possible solutions to the analysis of the fsQCA model are the complex, intermediate, and parsimonious solutions. The parsimonious solution, which includes all simplifying assumptions made in line with the researchers’ specific knowledge (Rey-Martí et al., 2022), is reported. Raw coverage shows the proportion of the outcome explained by a specific solution, whereas unique coverage shows the proportion of the outcome explained by each condition of a causal configuration (Florea et al., 2019). A configuration with low coverage is not always less relevant because it might be useful to explain a particular outcome (Ragin, 1987).

The results for the parsimonious solution that can be seen in Table 5 show six configurational paths. The coverage of the solution is 0.378932, indicating that the six causal configurations explain roughly 40 % of the empirical cases. The first and second causal configurations consist of three conditions: the negation of LEXP and the presence of NUPD for both configurations, and the negation of LVIDE and IDEN, respectively. The third causal configuration also contains three conditions: the negation of LBUDG and the presence of NIMAG and NUPD. The other configurations contain four conditions each: the negation of IDEN and LBUDG, and the presence of LVIDE and NUPD for the fourth configuration; the presence of IDEN, LBUDG, NIMAG, and LEXP for the fifth configuration; and the negation of IDEN and the presence of LVIDE, NIMAG, and NUPD for the sixth configuration.

Parsimonious solution.

| Causal configuration | Raw coverage | Unique coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| ∼LVIDE*∼LEXP*NUPD | 0.216116 | 0.0182038 | 0.842225 |

| ∼IDEN*∼LEXP*NUPD | 0.223447 | 0.0134466 | 0.875261 |

| ∼LBUDG*NIMAG*NUPD | 0.208592 | 0.0269417 | 0.879272 |

| ∼IDEN*LVIDE*∼LBUDG*NUPD | 0.158204 | 0.00917467 | 0.882959 |

| IDEN*LBUDG*NIMAG*LEXP | 0.0453884 | 0.0197086 | 0.873016 |

| ∼IDEN*LVIDE*NIMAG*NUPD | 0.145728 | 0.0174271 | 0.859926 |

Solution coverage: 0.378932 Solution consistency: 0.875014

Results are in line with the initial proposition, pointing to multiple alternative information disclosure strategies resulting in overfunding. Specifically, NIMAG always appears to be present (i.e. a high number of images favours campaign overfunding) and NUPD also always appears in the form of presence (i.e. a high number of updates by the entrepreneur favours campaign overfunding). For the other conditions, the results are mixed, as was particularly expected for the influence of the entrepreneur's identity on campaign overfunding. That is, both presence and absence of the condition can be found in the causal configurations.

5.1Detailed analysis of causal configurationsOf all causal configurations in the parsimonious solution, four are specific to a particular identity of the entrepreneur (individual or corporate). For the other two, identity is irrelevant. For corporate entrepreneurs, a concise explanation of the project and continuous communication with the crowd (Configuration 2), a concise budget explanation, long video, and continuous communication (Configuration 4), and a long video, large number of images, and continuous communication (Configuration 6) result in overfunding.

In the case of individual entrepreneurs, both the budget and the entrepreneurial project should be explained extensively and should be accompanied by a large number of images (Configuration 5). Thus, the results show that information disclosure should be more extensive for individual fund-seeking entrepreneurs. Finally, two causal configurations have no reference to the entrepreneur identity as a condition. In the first, overfunding is achieved through a concise explanation of the project and a concise video pitch, together with continuous communication from the entrepreneur to the crowd (Configuration 1). In the other, the budget must be concise, communication continuous, and the number of images high (Configuration 3).

5.2Overall findingsOverall, the following findings can be derived from the above causal configurations. However, their meaning only makes sense when considering the interrelationship of each condition with others in the form of configurations. They should not be interpreted as unidirectional relationships.

Finding 1. Maintaining a continuous communication with the crowd during the campaign matters.

The NUPD condition is present in five of the six causal configurations. This finding confirms the importance for entrepreneurs to maintain a fluid communication channel with the crowd through which they can resolve their queries and provide additional information to reduce information asymmetries.

Finding 2. The identity of the entrepreneur seeking funding matters.

This identity is a condition in four of the six causal configurations. In three causal configurations, being a corporate entrepreneur is identified as a success factor, while in another, being an individual entrepreneur is identified as a success factor. According to the results, individual fund-seeking entrepreneurs are expected to provide more extensive information in terms of images and the project and budget explanation.

Finding 3. In a number of pathways, the shorter the text, the better.

Both the LEXP and LBUDG conditions, which refer to the length of the project abstract and budget explanation, respectively, appear in two causal configurations each in the form of negation. Because the presence of these conditions would refer to having a long text, their negation (absence) suggests that the brevity of texts matters for campaign success.

Finding 4. Images about the project are relevant.

The NIMAG condition is present in three of the six causal configurations, suggesting that the greater the number of images, the greater the success.

The results reveal the central importance of maintaining ongoing communication with the crowd of prospective backers to mitigate information asymmetries and encourage overfunding in reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. This finding is in line with previous insights from De Larrea et al. (2019) and Xiao et al. (2021). It demonstrates the value of updating prospective backers with new information that may be relevant to them. The results also show that the specific information disclosure strategies depend on the identity of the fund-seeking entrepreneur, and that individual fund seekers must disclose more extensive information. Finally, as Koch & Siering (2019) noted for crowdfunding success, overfunding is also driven by a higher number of images. Concerning the text, although one information disclosure strategy suggests that longer texts might be preferred (for individual entrepreneurs), short texts are generally recommended.

The results also highlight the complexity of overfunding drivers in reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. This feature of the results suggests that further studies should include other elements of information disclosure that may influence a campaign's ability to raise large sums of funds. Accordingly, there may be evidence of omitted conditions (De Crescenzo et al., 2022; Radaelli & Wagemann, 2019).

5.3Theoretical contributions and practical implicationsThe implications of this study are of particular importance in relation to the design of crowdfunding campaigns that signal quality and result in overfunding. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of which information elements are behind campaigns that obtain high levels of funding (i.e. overfunding). In so doing, it adds to the theories of asymmetric information and signalling in digital fundraising environments. The findings highlight the critical role of updates in driving overfunding in reward-based crowdfunding. They also suggest that the phenomenon of overfunding can be explained by multiple information disclosure strategies, revealing the underlying complexity of the signalling process between entrepreneurs and potential backers.

From a practical point of view, the study offers a series of practical guidelines for fund-seeking entrepreneurs, potential backers, and intermediary platforms. For entrepreneurs, it is advisable to stay in constant communication with the crowd of potential backers. Images are likewise crucial in achieving overfunding. The results also point to the brevity of texts as an overfunding driver, although for individual entrepreneurs, longer texts are required. Finally, both individual entrepreneurs and corporations can achieve overfunding in reward-based crowdfunding, albeit through different information disclosure strategies.

These practical guidelines are also relevant for potential backers willing to invest in highly successful projects. Crucially, in all-or-nothing campaigns, backers have a special interest in ensuring that the project secures its target funding to avoid bearing an opportunity cost for the time the funds have been withheld if the campaign fails. Finally, the results provide insights to intermediary platforms, indicating which information elements should be prioritised to ensure that these platforms offer optimal tools for entrepreneurs to raise funds from the crowd. In this regard, it is recommended that intermediary platforms provide an intuitive updates section and facilitate the creation of image galleries so that entrepreneurs can visually convey relevant information about their entrepreneurial ideas.

6Conclusions, limitations and future lines of researchThe present study used fsQCA to explore the configurations of conditions that result in overfunding, which refers to achieving funding at least 10 % above target. The conditions employed in the study were campaign design factors associated with information disclosure by entrepreneurs to reduce information asymmetries. The conditions were the entrepreneur's identity as an individual or corporation [IDEN], pitch video length [LVIDE], budget explanation length [LBUDG], number of images [NIMAG], project abstract length [LEXP], and number of updates by the entrepreneur [NUPD].

The study offers two core findings. First, the configurations of conditions that result in overfunding suggest that the role of continuous communication from the entrepreneur to the crowd is especially relevant. Updates by entrepreneurs to the crowd of potential backers seem to serve as a mechanism to provide additional information about the entrepreneurial idea and campaign status with which to attract further contributions. Therefore, updates offer a dynamic way of engaging with potential backers to enhance the initial static information that entrepreneurs display when creating a reward-based crowdfunding campaign.

Second, a series of exploratory findings, which must always be interpreted under a configurational logic, suggest the importance of the identity of the entrepreneur, the brevity of the texts included on the campaign website, and the amount of visual content in the form of images. In addition to these findings, the study also provides evidence of the underlying causal complexity of the phenomenon of overfunding.

The study was limited by the sample size and the choice of conditions, which did not account for specific types of images, videos, or texts. Accordingly, the information elements considered in this study could be operationalised in a more qualitative manner by using techniques such as sentiment analysis or discourse analysis. In addition, there may be an issue in relation to omitted conditions of overfunding that were not considered in this study (De Crescenzo et al., 2022; Radaelli & Wagemann, 2019). Finally, the fact that the data were sourced from a single platform for a specific period limits the generalisability of the findings.

Further research could include a more detailed study of text content using text mining, given that this study only considered text length. Similarly, discourse analysis could be applied to videos to explore how the entrepreneurial idea is conveyed by fund seekers. This line of study could be further developed by analysing overfunding for different forms of crowdfunding (e.g. equity-based crowdfunding or crowdlending) and fundraising dynamics (e.g. all-or-nothing and keep-it-all campaigns), as well as by using data sourced from platforms in different geographic markets. Furthermore, this research area would benefit from economic experiments aimed at monitoring human behaviour in crowdfunding environments. Additionally, the use of complementary methods (e.g. regression analysis) would be interesting, especially in terms of validating the identified causal paths and assessing their predictive capabilities.

CRediT authorship contribution statementPau Sendra-Pons: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Dolores Garzon: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. María-Ángeles Revilla-Camacho: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Pau Sendra-Pons acknowledges the Spanish Ministry of Universities for funding under FPU2019/00867 to support this research. Dolores Garzon and Pau Sendra-Pons acknowledge Generalitat Valenciana for funding under Project GV/2021/121 to support this research.

Throughout this study, the term corporate entrepreneur is used to refer to a fund-seeking entrepreneur (or team of entrepreneurs) constituted as a company. It should not be confused with the phenomenon of intrapreneurship.

This platform is categorised as reward-based crowdfunding because each campaign offers a number of rewards to potential contributors (e.g. a sample product). However, the platform shares with the donation-based crowdfunding model the fact that often one of these rewards is simply explicit recognition for a monetary contribution to the project.