Pancreatitis is a common disease with varied aetiology, and can give rise to various complications. We present a previously unreported complication: portal vein thrombosis (PVT) associated with necrosis of liver segments II/III.

A 76 year-old man seen in the emergency room for abdominal pain lasting 48h accompanied by nausea, choluria and acholia. Personal history: hypertension and HLA-B27 ankylosing spondylitis, denies alcohol abuse. Examination: T: 36.4°C; BP: 135/85mmHg: HR: 129bpm; conjunctival icterus and diaphoresis; abdominal pain in epigastrium and both hypochondria with positive Murphy sign. Preliminary laboratory results: white blood cells: 18,000/¿L (92% neutrophils); haemoglobin 16.6g/dL; serum amylase 3549U/L; ALT: 259U/L; AST: 326U/L; alkaline phosphatase: 182U/L; total bilirubin: 9.8mg/dL (direct: 7.2mg/dL); C-reactive protein: 53.6mg/dL and plasma lactate: 2.3mg/dL.

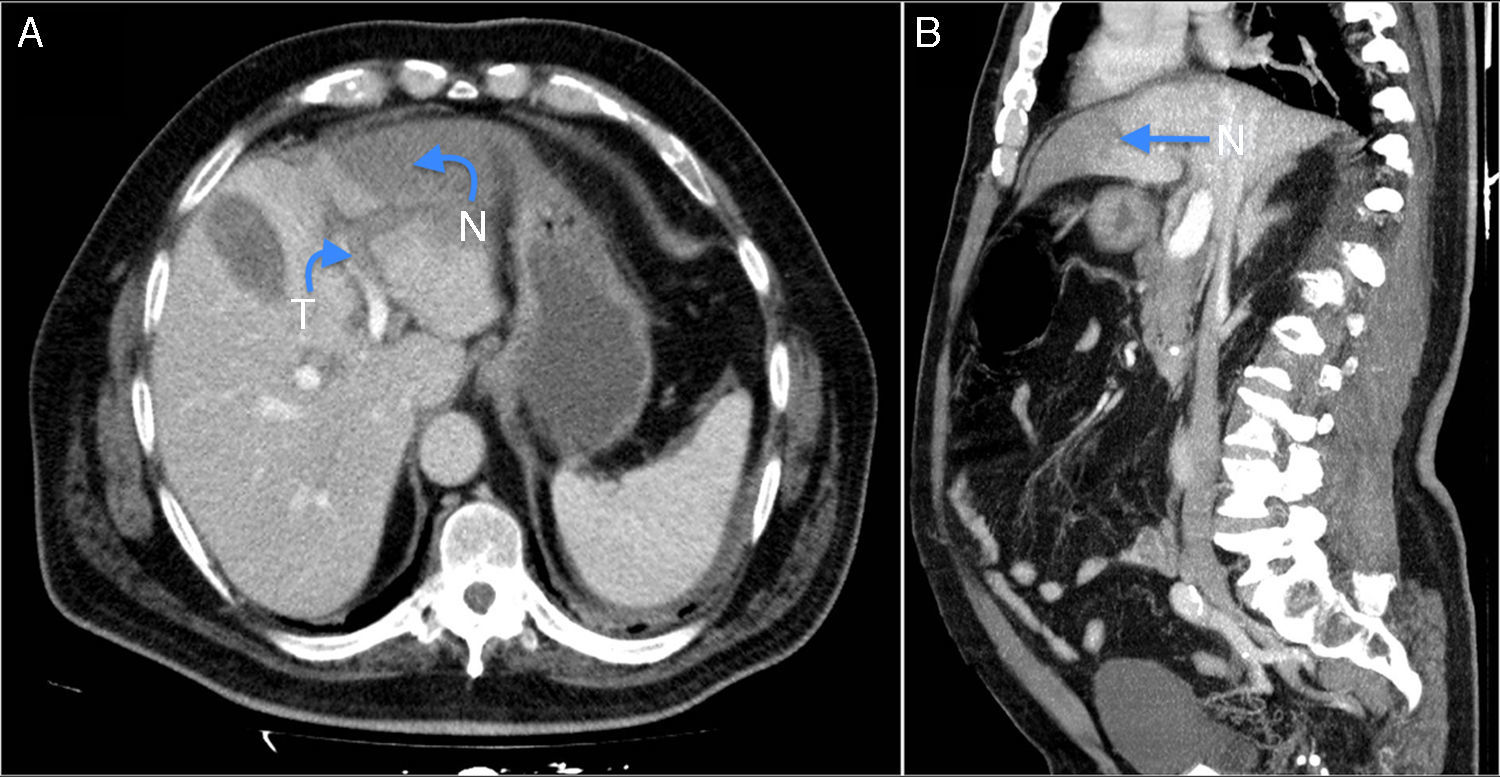

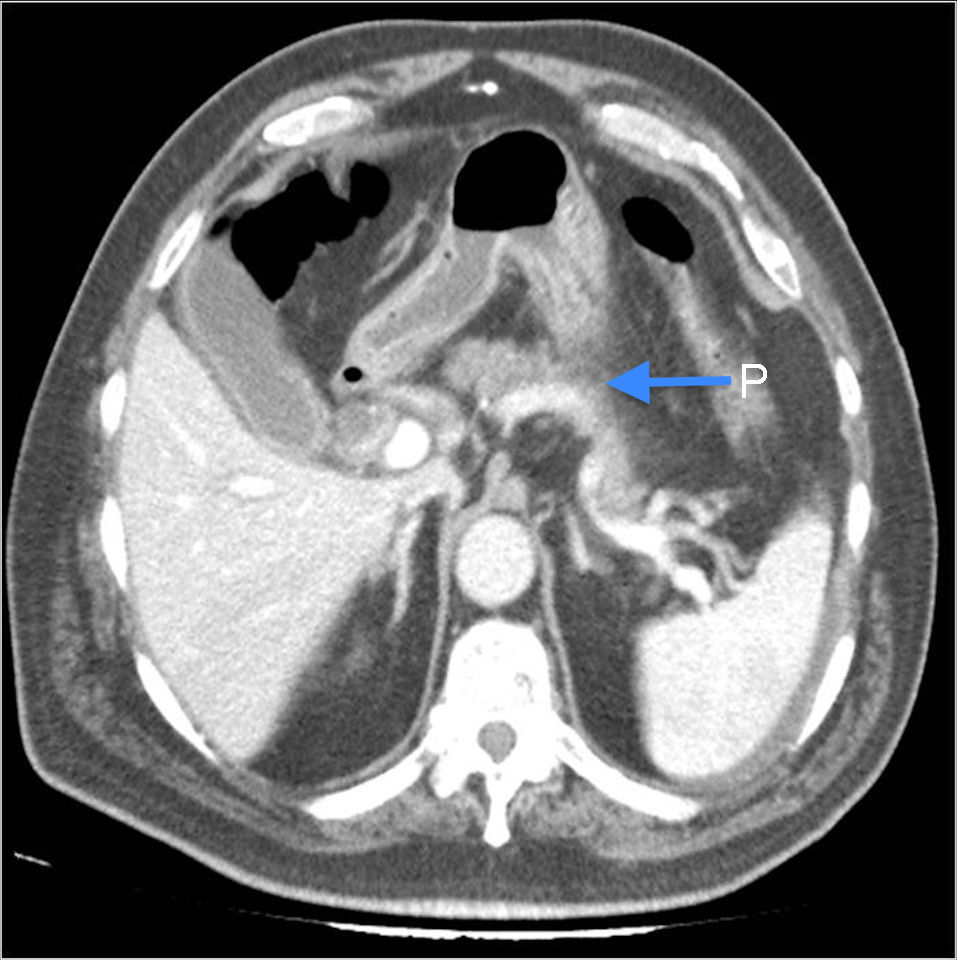

Abdominal ultrasound showed gallbladder sludge and gallbladder wall thickening of 4mm. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed signs of left portal vein thrombosis with lateral hepatic infarction (Fig. 1); small amount of perihepatic and perivesicular ascites; dilated common bile duct (13mm) and pancreatic oedema (Fig. 2).

Treatment was started with sodium heparin and empirical antibiotic treatment (Imipenem®). At 48h the patient presented fever, hypotension, leukocytosis and increased CRP. A new CT scan showed increased amounts of intraabdominal free fluid associated with clinical worsening and haemodynamic instability, despite intensive treatment. Emergency surgical treatment was decided, showing, 2.5L choleperitoneum, necrosis of liver segments II/III; canilicular perforation on the surface of the liver with release of bile. Left lateral hepatectomy was performed with cholecystectomy and exploration of the bile duct, which showed gallbladder sludge. Choledochotomy was closed after placement of a Kehr T-tube. Peritoneal fluid culture was sterile. Histology revealed extensive hepatic necrosis. After surgery, improvement was observed in symptoms, and pathological analytical parameters were normalized.

During his hospital stay the patient presented pneumonia and kidney and heart failure. He was discharged 95 days after surgery. Systemic causes of the thrombosis were ruled out. One year after discharge, the patient died suddenly at home while still receiving acenocoumarol therapy. No autopsy was performed.

Partial or complete PVT is a relatively common complication in patients with liver cirrhosis, although it can also occur in the absence of underlying liver disease.1 Non-cirrhotic PVT can be caused by local (surgery, pancreatitis, pancreatic tumour)2 or systemic factors (coagulation disorders, myeloproliferative disorders and prothrombotic conditions, such as Factor V Leiden mutation and protein C deficiency).1,2 Prevalence of PVT in acute pancreatitis is estimated at 8%.3

The aetiology of PVT in acute pancreatitis is multifactorial: cross-talk between coagulation and inflammatory pathways, elevation of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1 and IL-6), which in turn regulate the increase in thrombin formation and reduce antithrombotic mechanisms,4 and pancreatic neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into the portal vein.

PVT can be acute or chronic, and depends on re-canalisation to permit collateral circulation. Acute PVT is characterized by intestinal congestion that can progress to ischaemia, causing pain or bloating, diarrhoea, bleeding, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fever, lactic acidosis, splenomegaly and sepsis. Chronic PVT can be almost asymptomatic due to re-canalisation, but the presence of oesophageal varices can cause gastrointestinal bleeding in 20–40% of cases.1 The highest diagnostic yield in PVT is obtained with Doppler ultrasound (81% sensitivity and 93% specificity) and CT or MRI angiogram, which show the extent and characteristics of PVT (sensitivity 96% and specificity close to 100%).1 The best method for diagnosing hepatic infarction is gadoxetate disodium contrast-enhanced MRI, which shows the extent of the infarction, hepatic haemodynamics and hepatocellular function, differentiating between areas of hepatic infarction and reduced perfusion.4,5

Few studies have described the complications associated with acute pancreatitis.6 We searched the PubMed database updated to 25-10-2015, with no language or date limitations, using the following string: (Pancreatitis) AND (Portal Thrombosis) AND (Hepatic Necrosis), and retrieved only 11 articles. After reading the studies, we found one case of hepatic infarction associated with portal vein thrombosis in a patient with chronic pancreatitis who died from liver failure.4 Another article described a case of hepatic necrosis and portal vein thrombosis in a patient with chronic pancreatitis after placement of a pancreatic stent,7 while another study discussed a case of hepatic necrosis and portal vein thrombosis in a patient with liver cirrhosis following variceal ligation and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy.8 A less restrictive search using the string (Pancreatitis) AND (Portal Thrombosis) returned 260 studies in venous thrombosis (splenic, portal and mesenteric) associated with acute pancreatitis, include a meta-analysis of 947 studies, published in 2015, none of which associate portal thrombosis with hepatic necrosis.3

There are no randomized trials on the treatment of acute PVT, but anticoagulation therapy is the most widely accepted strategy. Re-canalization rate is 70% if anticoagulation is initiated in the first week of diagnosis, and 25% if started later.1 Anticoagulation should be maintained for at least 2–4 weeks, and later replaced with oral anticoagulants, which should be maintained for a year. Other therapeutic strategies, such as local or systemic administration of thrombolytic agents should only be used in the event of total or partial therapeutic failure.9 However, we could find no recommendations in the literature regarding patients like ours, in whom the cause (pancreatitis) has resolved, and who have undergone hepatic and portal vein resection, removing the thrombus. We are unsure whether anticoagulation is necessary in these cases, and if so, how long it should be maintained. In hepatic infarction, treatment and prognosis depends on the extent of injury; partial infarction should be treated conservatively, while lobar or more complicated infarction require hepatectomy of the affected area.10

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Gonzales Aguilar JD, Ramia Angel JM, de la Plaza Llamas R, Kuhnhardt Barrantes AW, Ramiro Perez C, Valenzuela Torres JC, et al. Trombosis portal y necrosis hepática: complicación excepcional de la pancreatitis aguda. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:88–90.