Pancreatic tuberculosis (TB) is rare, especially in immunocompetent patients. Its manifestation as a pancreatic mass represents a diagnostic challenge as it may be falsely identified as a malignancy of the pancreas.1

We present the case of a 70-year-old man who attended our hospital following seven days of left abdominal pain, fever, anorexia and asthenia, with deteriorating general condition. His personal history of note included dilated cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation, receiving anticoagulant therapy with coumarin derivatives. The patient reported no substance abuse.

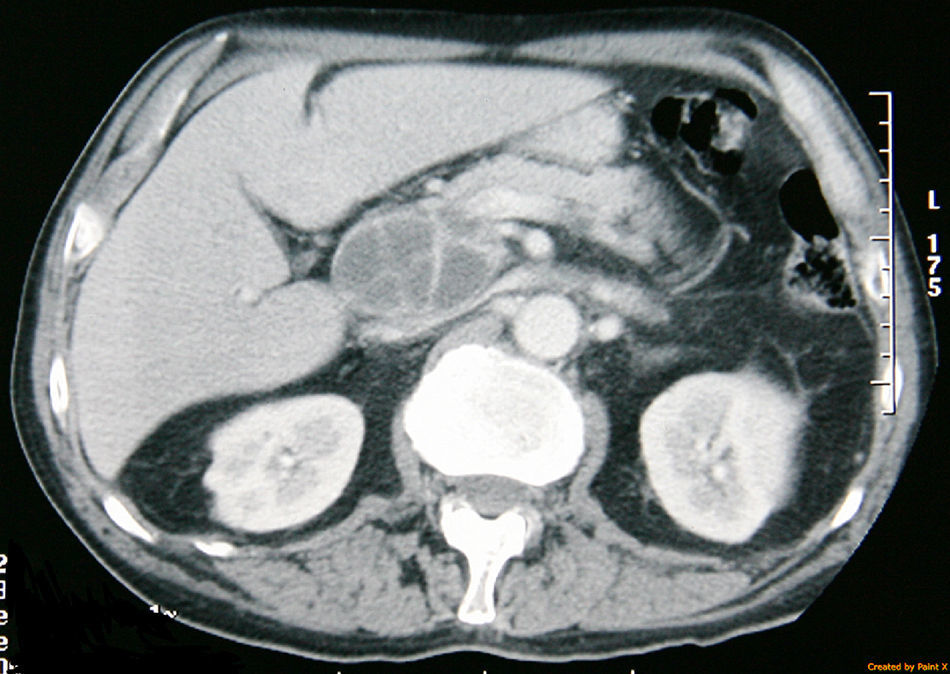

During the physical examination, the patient was sweaty, with BP 95/65mmHg and a temperature of 37.5°C. The patient experienced pain in the epigastrium and left upper quadrant upon abdominal palpation, with no signs of peritoneal irritation. The chest and abdominal X-rays found no relevant abnormalities. The blood tests revealed altered liver biochemistry levels (AST 114IU/l, ALT 94IU/l, ALP 371IU/l and GGT 877IU/l). The blood and urine cultures were negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a cystic mass in the head of the pancreas measuring 5×5cm in diameter, containing septa, as well as retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies and lymphadenopathies at the hepatic hilum and coeliac artery (Fig. 1). Serum amylase, lipase and CA 19-9 levels were normal. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed. Material that appeared purulent was extracted, which was found to be negative for malignant cells and consistent with an inflammatory process with polymorphonuclear leukocytes and cellular detritus. No bacterial or fungal growth was found.

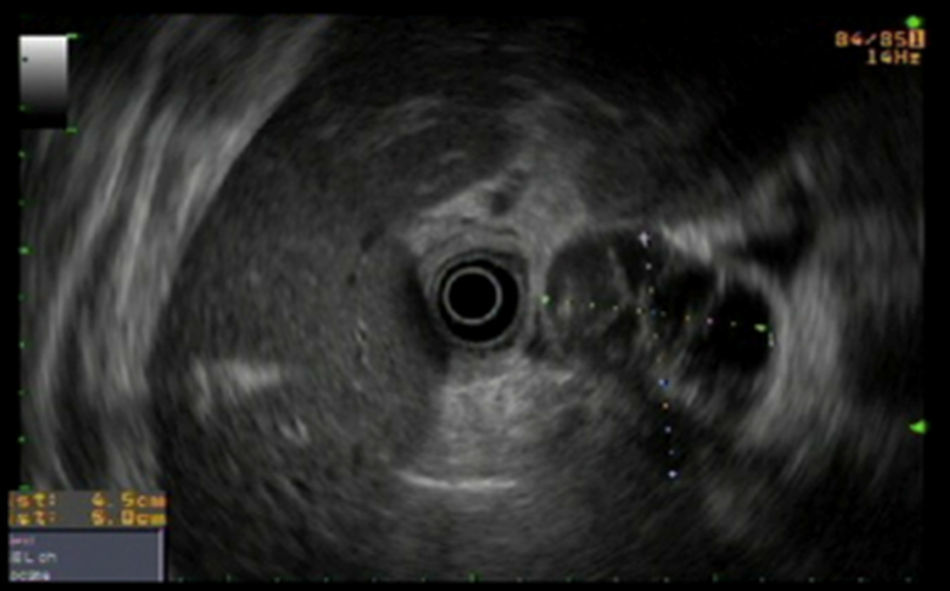

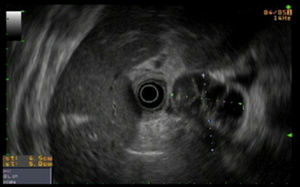

Despite treatment with imipenem and antipyretics, the clinical course was poor with persistent fever. As a result, it was decided to conduct endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage. A hypoechoic and heterogeneous mass measuring 5×4mm was identified adjacent to the wall of the duodenal bulb (Fig. 2) and a round lymphadenopathy measuring 8mm was found at the hepatic hilum. The mass was punctured from the duodenum and a metallic prosthesis and a nasopancreatic drain were placed.

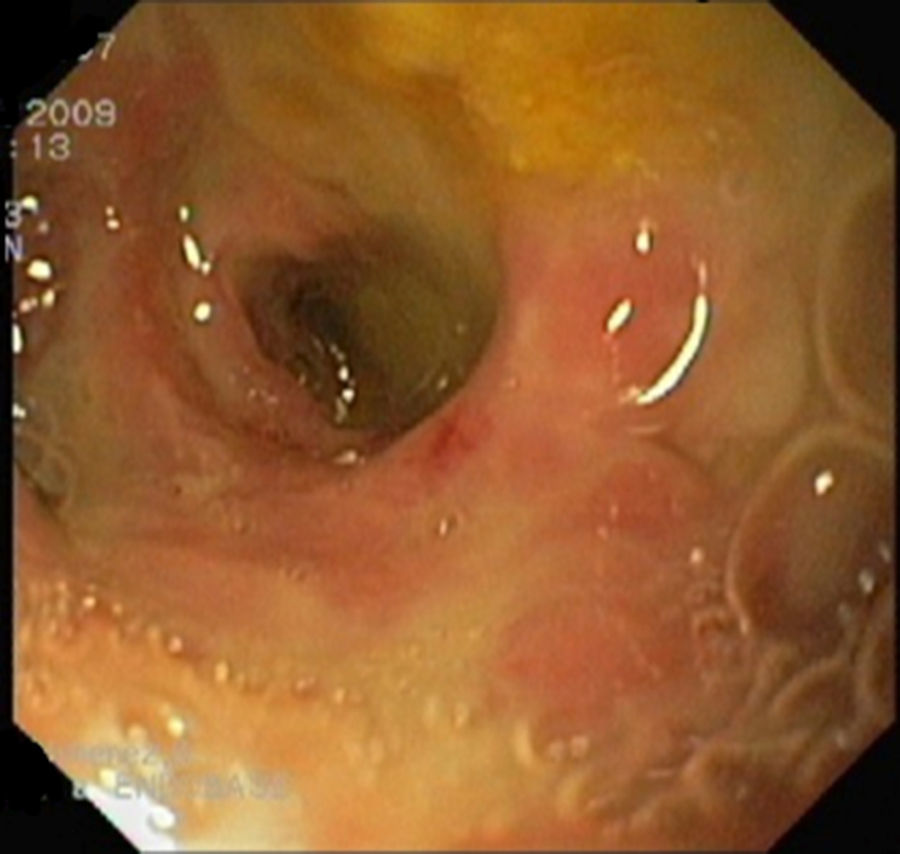

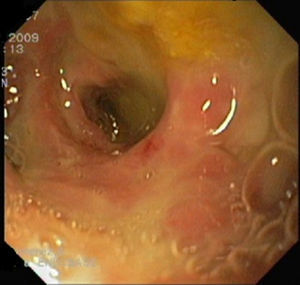

Given the patient's persistent fever despite modifying antibiotic therapy (tigecycline, ceftazidime, fluconazole) and poor drainage flow rate, the cystic duodenal fistula was reviewed by gastroscopy. The pancreas was accessed, which was found to contain detritus in its walls (Fig. 3), and biopsies were taken. During admission, a round, painful and palpable lymphadenopathy of the left laterocervical region, with a major axis measuring 3cm, was identified and subsequently resected.

The histological examination of the lymphadenopathy confirmed that it was necrotising granulomatous lymphadenitis. The histological examination of the pancreas biopsies confirmed the presence of necrotic inflammatory tissue. Both examinations found acid/alcohol-fast bacilli (AAFB). Given these findings, antituberculosis treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide was prescribed for two months, with rifampicin and isoniazid administered for a further nine months. The patient was asymptomatic by the end of treatment. No abnormalities of the pancreas were found on a CT scan conducted two years later for other reasons.

Pancreatic TB is rare and its isolated manifestation tends to be associated with miliary tuberculosis.2,3 Abdominal TB accounts for 12% of extrapulmonary TB cases.4 In order, from most common to least common, it may involve the ileocaecal junction, the peritoneum, the spleen, the liver or the pancreas.5 It is believed that infection of the pancreas may be caused by lymphatic or haematogenous dissemination, or by reactivation of a previous latent infection.6 It may manifest as acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic abscess, gastrointestinal bleeding or obstructive jaundice. It may also present as an isolated pancreatic mass mimicking pancreatic carcinoma. Some cases of pancreatic cancer with TB have been reported. This range of different manifestations makes pancreatic TB difficult to diagnose.3,6,7

Findings from imaging tests may be consistent with pancreatic TB, but no finding is unique to that disease. As a result, experience and a high level of suspicion are required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Histopathological, cytological or microbiological confirmation is required in all cases. Pancreatic biopsy techniques include ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous biopsy, endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNAB or surgical biopsy.5,7,8 Diagnosis is facilitated by granulomas, epithelioid histiocytes with plasma cells and lymphocytes, and, more rarely, acid/alcohol-fast bacilli. Although the culture is highly specific, it is slow and less sensitive.8

Once the diagnosis has been established, antituberculosis treatment should be administered for 6–12 months. The initial phase consists of two months of intensive TB treatment with multiple drugs (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol), followed by a continuation phase of rifampicin and isoniazid for at least four months.9

In conclusion, pancreatic TB is a rare condition that tends to arise in the context of miliary or disseminated tuberculosis. Like chronic pancreatitis or autoimmune pancreatitis, it may mimic a pancreatic malignancy, making it difficult to diagnose. As such, in patients with a space-occupying lesion of the pancreas and unexplained fever, a diagnosis of pancreatic TB should be considered.

Please cite this article as: Mora Cuadrado N, Berroa de la Rosa E, Velayos Jiménez B, Herreros Rodríguez J, Abril Vega CM, de la Serna Higuera C, et al. Tuberculosis, un diagnóstico más a tener en cuenta ante una masa pancreática. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:619–621.