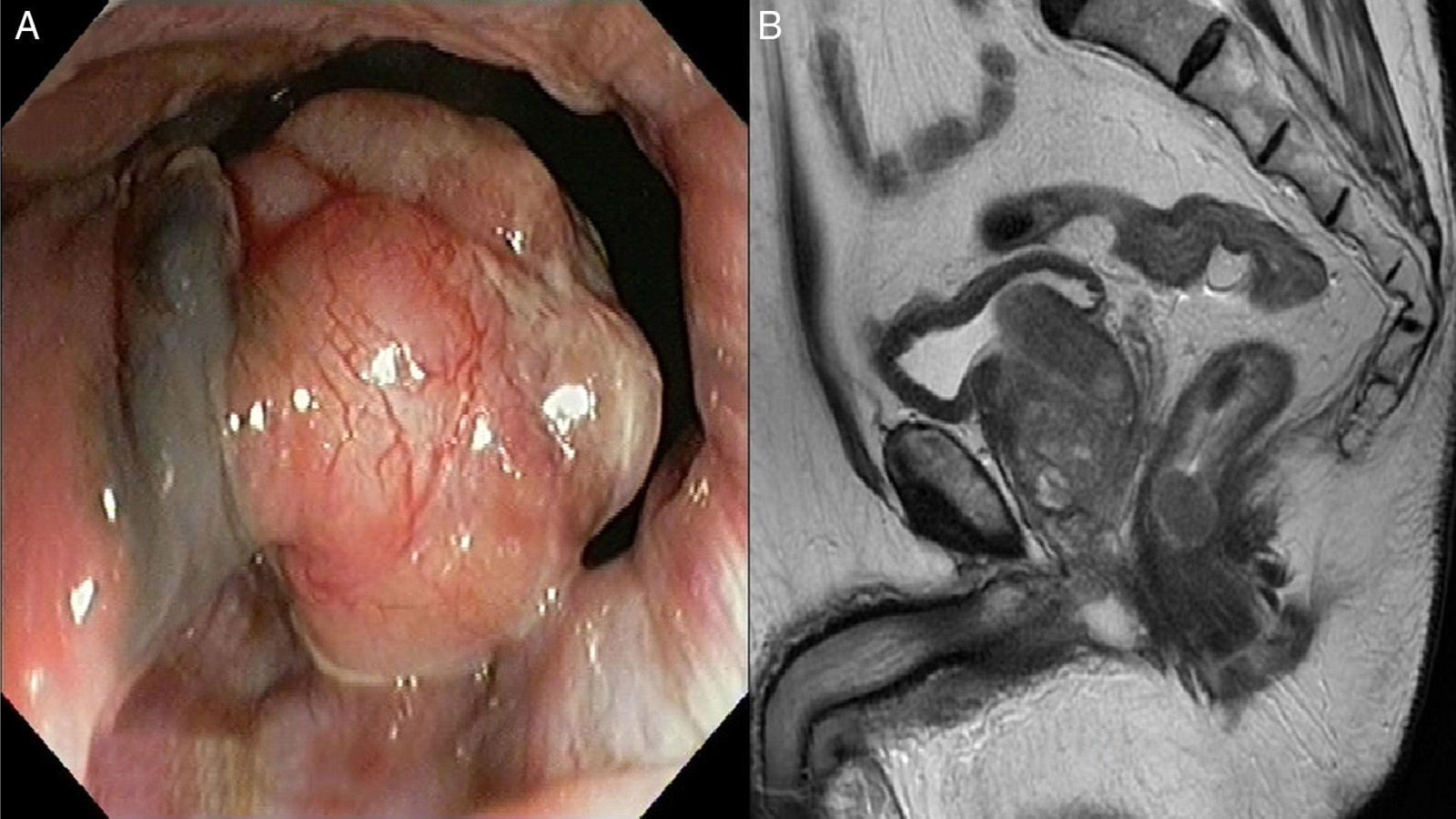

We present the case of an 81-year-old man with previous diagnose of hypercholesterolemia, benign prostate hyperplasia and seborrheic keratosis. He presented a two-months history of rectorrhagia episodes without any other symptoms. In the laboratory tests there was no anemia and the tumor markers were negative. A rectoscopy was performed identifying from the anus to 6cm beyond the dental line a pseudo-polyp mameloned tumor with hyperpigmented base evolving a quarter of the whole circumference of the rectum (Fig. 1A).

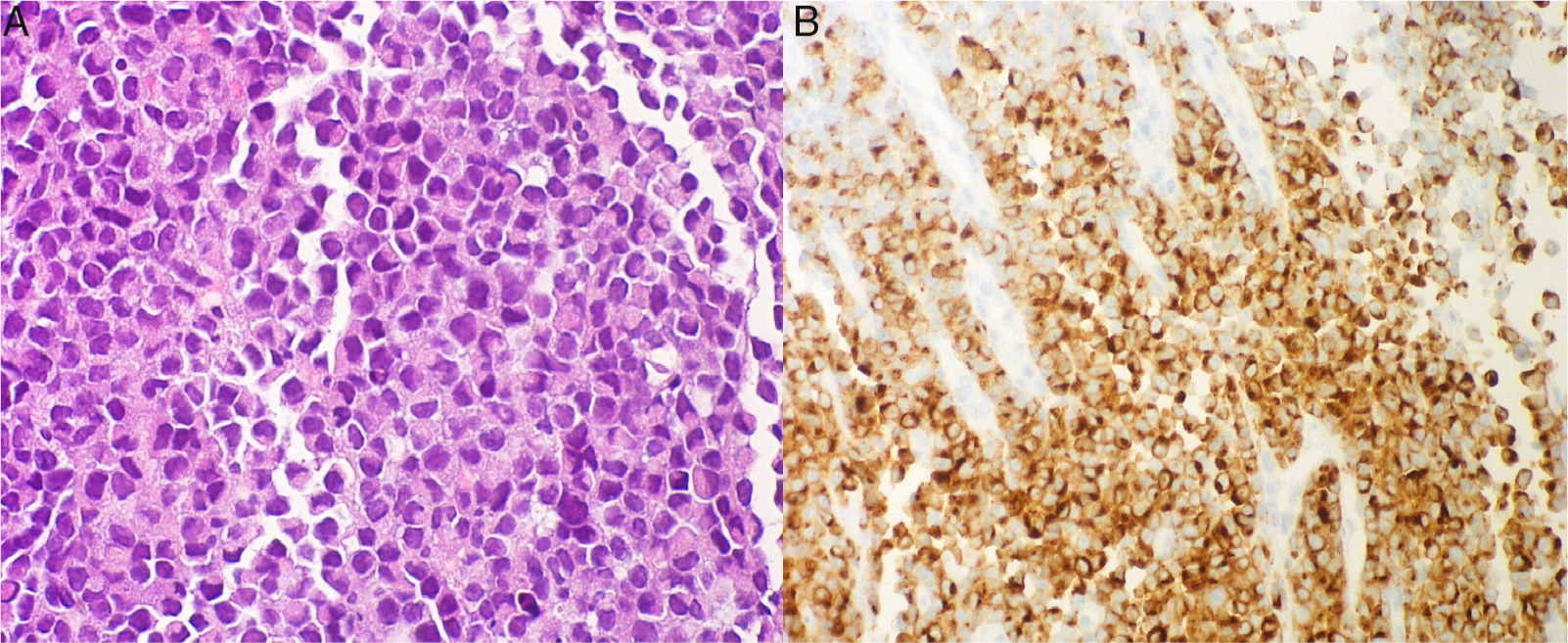

The biopsies showed extended small round cells proliferation with necrosis. Neither melanic pigment nor mucosa was observed probably because superficial biopses where taken on the surface of the tumor. The immunophenotype was negative to S-100 and positive to Melan-A and MITF (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) so the diagnose of a rectal melanoma was performed (Fig. 2A and B). The study was completed with colonoscopy (three adenomatous polyps were removed), pelvic magnetic resonance (Fig. 1B) and computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen without mesorectal lymph nodes or distal metastasis. The case was presented in the multidisciplinary comity and a surgical approach was chosen. An endoanal resection was performed, because of the absence of distal or local invasion and the patient age and comorbility, without complications. The surgical piece showed deep infiltration even throws muscular propia, an ulcerated mucosa and the presence of melanophages. The patient remains asymptomatic and with good quality of life.

Mucosal melanomas (MM) are rare (0.4–1.6% of total malignant melanomas). Both cutaneous and mucosal melanomas contain melanocytes, but have important differences such as the exposure of ultraviolet light (clearly related with cutaneous melanoma), localization, appearance (40% in MM are amelanotic) age of presentation and prognosis (poorly in the case of MM).1–5

The anus is the third most common location of melanomas after the skin and the eyes.1,3,4 MM arise primarily in the head and neck (55%), anorectal (24%) and vulvovaginal (18%) regions and are in 20% of cases multifocal.1,3,5 They are frequently found within 6cm of the anal rim: rectum (42%), anal canal (33%) or both. Other infrequent sites include urinary tract, gall bladder and small intestine. The median age of presentation is 70 years (except those located in oral cavity found in younger people). There is a female preponderance of cases and HIV infection has been implicated as a risk factor for anal localization in young male patients.1,2,6 The incidence of anorectal melanoma (AM) increases over time, and it remains highly lethal, with a 5-year survival rate of 6% to 22%. The simplified staging system which was originally developed for melanomas of the head and neck in 1970 by Ballantyne is used for the primary site including three stages Stage I: Localized disease; Stage II: Locoregional nodal involvement and Stage III: distant metastatic involvement.7 The most common presenting symptoms are nonspecific and include rectal bleeding followed by pain, the sensation of a mass, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and tenesmus. All of them present in such common conditions as are hemorrhoids, rectal polyp or prolapse. As the diagnose is usually late the tumors may attain a large size before being correctly diagnosed. Metastases are present at the time of diagnosis in more than half of patients.2,4,5,7-9 Although melanomas develop throughout the anus, two thirds arise in the proximal portion of the pecten and transitional zone around the dentate line (within 6cm of the anal rim). Twenty to fifty percent of tumors are pigmented but others remain amelanotic.1,2 Histologically the cells are often large with an epithelioid appearance and finely distributed pigment giving the cytoplasm a dusty-tan appearance. We can find large hyperchromatic nuclei with well-dispersed chromatin, multinucleated and polymorphic giant cells. Some melanomas (small round cell melanomas) contain atypical round cells resembling lymphocytes. Intraepithelial extensions of malignant melanoma may be confused with Paget disease. Immunohistochemistry studies can be useful, as AM stains positive for anti S-100 protein, HMB-45 (as the S-100 is a monoclonal antibody, HMB-45 that reacts against an antigen present in melanocytic tumors such as melanomas, and stands for human melanoma black 45) and Melan-A, while are usually negative for AE1/AE3 cytokeratines.4

A correct diagnose includes radiological exams including tomography scan (for the evaluation of distal dissemination), magnetic resonance (for local evolving) and even endoscopic procedures such as ecoendoscopy for a detailed examination of the area in order to a better surgical approach.8,9

Given the rarity of this neoplasia, optimal treatment is still controversial and surgery seems to be the only curative treatment. Surgical approaches include wide local excision (WLE) and abdominoperineal resection (APR), although no one has demonstrated survival advantage. However with the wide and complete resection (R0 oncological criteria) the surveillance of patients for 5 years rounds the 19% in contrast to the 6% if the margins are affected.7,8,10,11

WLE is the procedure of choice when the complete excision of the tumor is possible, as it is accompanied by a less morbidity rate and less functional limitations. In contrast, it presents higher rates of local recurrence. If is not possible the complete excision with WLE, in this situation, APR and local radiotherapy may improve loco-regional control, despite a lack of demonstrable impact upon overall survival.8–11

In conclusion, primary anorectal melanoma is an extremely rare and aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis that it is often misdiagnosed. High suspicious is mandatory to achieve early-diagnosis.2,8,9