Acute cerebellitis is an inflammatory condition that often involves an infectious aetiology and usually follows a benign course. Cases of autoimmune origin are rare, and cases associated with inflammatory bowel disease are anecdotal. Clinical suspicion, as well as its correlation with complementary tests and a congruent therapeutic response, leads in these few cases to the diagnosis of the condition.

A 37-year-old-male with a personal history of Crohn’s disease in the ileum featuring a penetrating pattern with entero-enteric and ileo-vesical fistulas for which he had undergone surgery, on treatment with 40 mg of adalimumab weekly, went in for left hemicranial headache accompanied by paresthesia in his upper limbs and blurred vision in his left eye.

On examination, the patient was alert and orientated, presenting intermittent horizontal diplopia, paresis on abduction of his left eye with no associated diplopia, hyperreflexia and postural tremor in all four limbs, with no dysmetria or dysdiadochokinesia. While standing, he maintained his balance and presented a gait with a slight increase in base of support.

He underwent laboratory testing which showed: glucose 114 mg/dl; urea 18 mg/dl; creatinine 0.57 mg/dl; total bilirubin 0.46 mg/dl; GGT 55 U/l; GOT 17 U/l; GPT 36 U/l; alkaline phosphatase 86 U/l; Na 143 mEq/l; K 3.69 mEq/l; C-reactive protein 0.45 mg/dl; haemoglobin 12.5 g/dl; leukocytes 7,200/mm3; platelets 341,000/mm3; aPTT 24 s and D-dimer 0.70 mg/l. No abnormalities were found in thyroid hormones, immunoglobulins G, A and M, vitamin E, vitamin B12 or folic acid. Serology for HIV, syphilis, toxoplasma, CMV, Epstein–Barr virus, brucella, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae was negative.

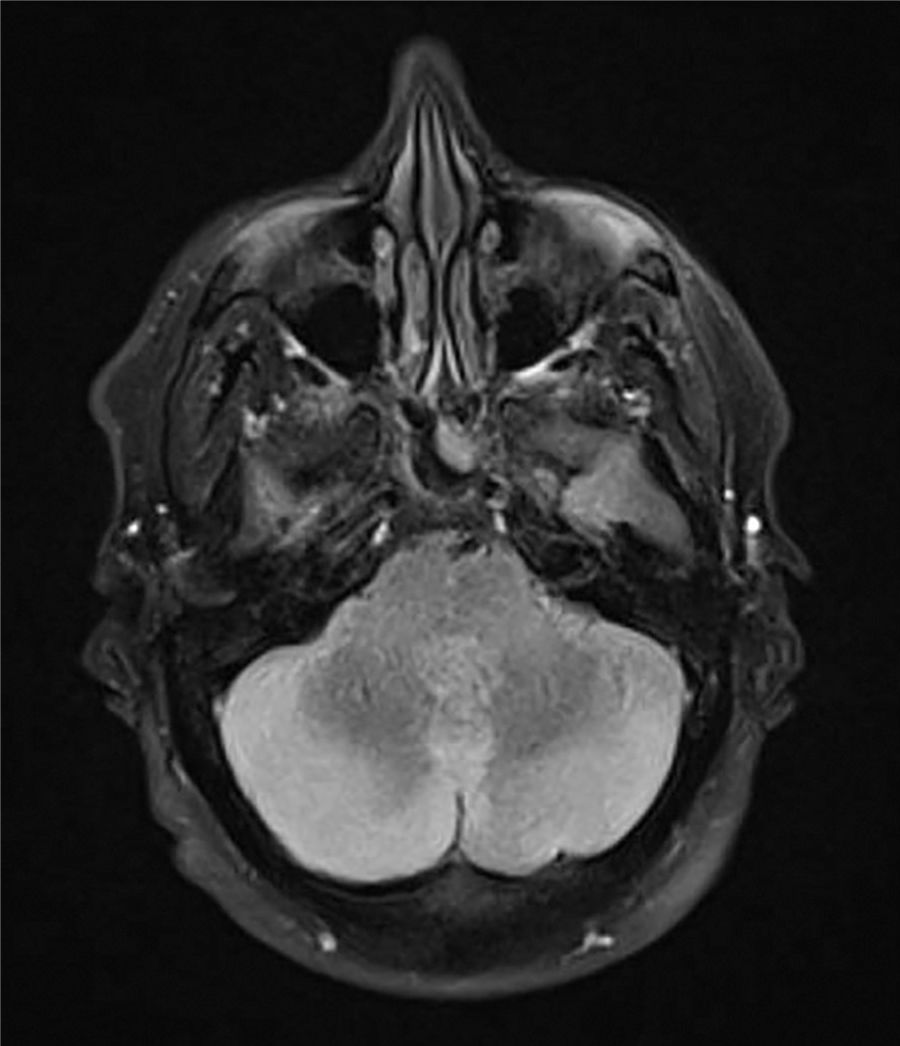

A CT scan of the head showed a slight diminishment of the extra-axial spaces in the posterior fossa with slight dilation of the third ventricle and lateral ventricles, whereupon cerebral venous thrombosis was ruled out. A thoracoabdominal CT scan and lumbar puncture showed no significant findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was ordered and reported an increased signal on T2 and flair in the cerebellar lobes, with a compression effect on the fourth ventricle, accompanied by a slight drop in the cerebellar tonsils in the context of signs of hypertension in the posterior fossa secondary to cerebellitis, of probable autoimmune aetiology (Fig. 1). Following empirical intravenous treatment with 50 mg of methylprednisolone every 24 h, the patient showed clinical improvement and remained asymptomatic following five days of treatment, with no signs of recurrence following six months of follow-up on an outpatient basis.

The search for an aetiology led to further blood testing, which revealed positive antinuclear antibodies (titre 1/160) with a mottled pattern. These things, together with the patient’s good clinical response to treatment and imaging test findings, led to a diagnosis of autoimmune cerebellitis in a patient with Crohn’s disease.

Acute cerebellitis is an isolated clinical syndrome that characteristically affects a paediatric population. In most cases, it involves an infectious, post-infectious or post-vaccine phenomenon, and its course is usually benign. This disorder is rare in adults and has a varied aetiology, with few cases of autoimmune origin,1 in which it is possible to distinguish cases associated with paraneoplastic syndromes from idiopathic cases.

The majority of neurological disorders associated with inflammatory bowel disease include cerebrovascular disease, peripheral neuropathies and demyelinating diseases; the finding of hypercoagulation phenomena promotes the development of venous sinus thrombosis.2

Clinically, it presents with varied manifestations ranging from mild cerebellar signs to signs and symptoms characteristic of brain stem impairment. Generally, the syndrome starts with ataxia, myoclonus and spontaneous abnormalities of eye movements, to which headache, nausea, fever, altered level of consciousness, seizures, meningeal signs and other cerebellar signs are added.3

Radiologic imaging of cerebellitis is variable: a CT scan may reveal modest low-density symmetrical and bilateral changes in the cerebellar hemispheres, which may be overlooked. Magnetic resonance imaging showed hypointense signals on T1 and hyperintense signals on T2 and sometimes cerebellar impairment may extend to the brain stem.4

Treatment varies by aetiology and clinical course, ranging from medical treatment to approaches that involve surgical decompression and external ventricular drainage in cases of obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to fulminant cerebellitis. In general, as in inflammatory bowel disease, management of this condition is based on the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants.5 However, the rarity of these cases makes it difficult to conduct studies on the potential benefits of immunosuppressive treatment for the condition’s course and recurrence.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Práxedes González E, Lázaro Sáez M, Hérnández Martínez Á, Vogt Sánchez EA, Arjona Padillo A, Vega Sáenz JL. Cerebelitis autoinmune en enfermedad de Crohn. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2019.06.002