Diverticular bleeding (DB) is a common cause for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Its incidence is increasing due to the aging of population, as colonic diverticula are more frequent in the elderly.1 The pathogenesis of DB is related to proliferation and weakening of the associated vas rectum of the diverticula conditioned by colonic luminal factors.1 Hypertension, arteriosclerotic disease and regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with higher risk of DB.1 In the majority of the patients DB stops spontaneously and the bleeding diverticulum is not identified in colonoscopy. However, in about 10–20% of the cases, bleeding reoccurs.2 This can be a serious condition, particularly in old patients with comorbidities. Proposed therapeutic options for DB encompass endoscopic hemostasis, embolization and surgery. Endoscopic hemostatic methods may include clipping and endoscopic band ligation (EBL). In a series of 100 patients, EBL was superior to endoscopic clipping (EC) in the treatment of colonic DB.3 We present a case of major colonic DB controlled with EBL.

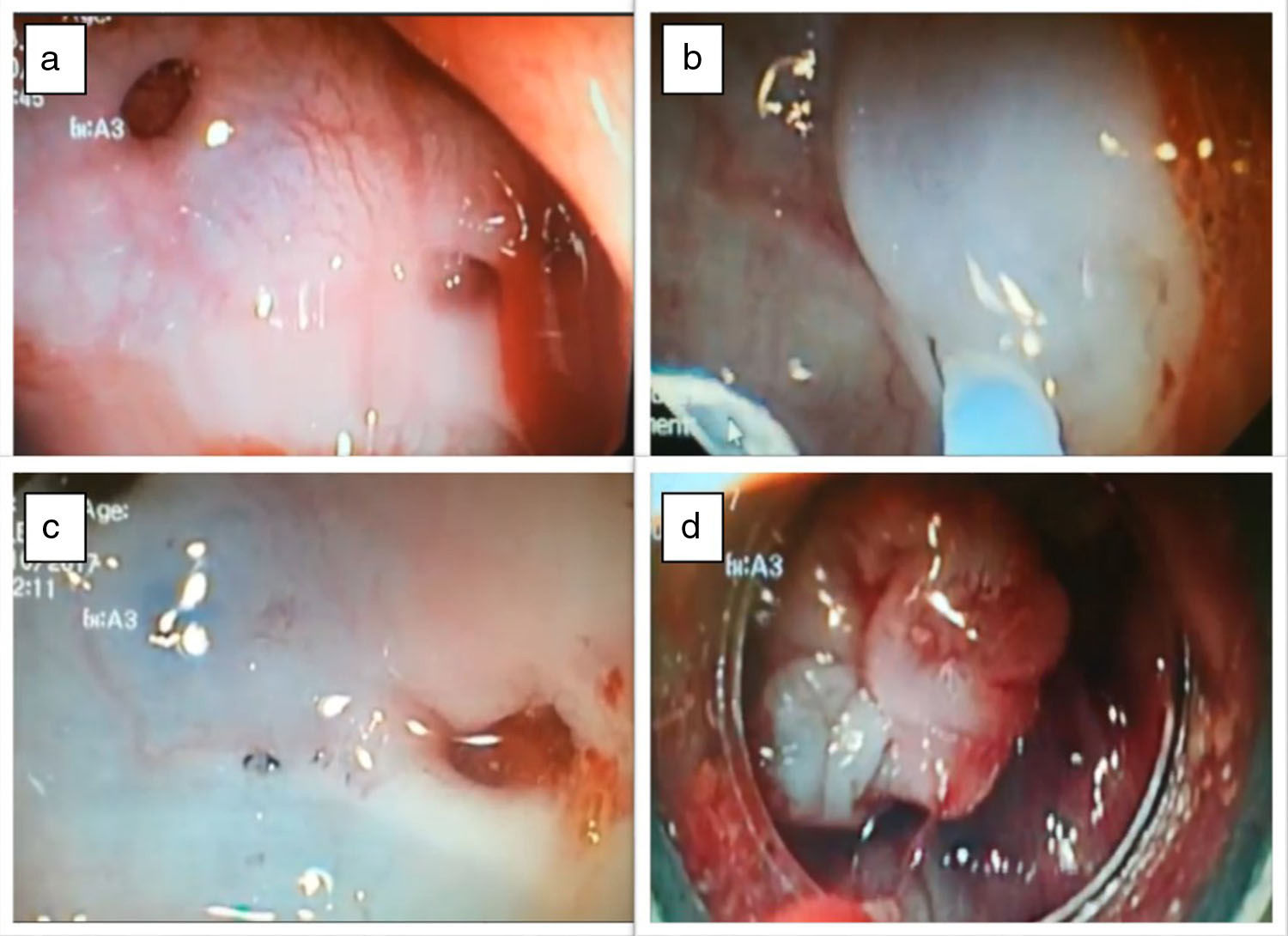

A 69-year-old male patient with coronary disease under clopidogrel, was admitted to our emergency room with bright red blood hematochezia and syncope. On admission, he was pale, hypotensive and tachycardic. Abdominal examination was unremarkable and nasogastric aspirate was bilious, without blood. Laboratory revealed acute normocytic anemia of 6.1g/dl (previous value 13g/dl) and no elevated markers of acute ischemic heart disease. He was stabilized with fluids and blood transfusion, and an urgent upper endoscopy was performed, showing no alterations, namely blood or the cause of bleeding. Bowel preparation was started and a total colonoscopy was performed, within the first 24h after admission; it showed no blood and multiple non bleeding left side colonic diverticula. In the next 24h, the patient presented again with hemodynamic instability and was admitted to our ICU. He was submitted to a second colonoscopy (after fast intestinal preparation) which showed fresh blood along the left colon and colonic diverticula. It was possible to identify the bleeding diverticula, with pulsatile hemorrhage in the sigmoid colon (Fig. 1a). Adrenaline (dilution 1:1000) was injected around the bleeding diverticula, conditioning mucosal elevation in the diverticular area (Fig. 1b); the bleeding was temporarily controlled. After that, endoscopic tattooing was performed to allow identification of the bleeding diverticula (Fig. 1c). Upper variceal band ligation kit was prepared and a conventional gastroscope was introduced; the marked diverticula was easily identified and a rubber ligation band was placed, surrounding and everting the diverticula (Fig. 1d). No active bleeding was seen by the end of the procedure. In the next 2 days, the patient remained stable, without blood loss despite reintroduction of clopidogrel. He was discharged 5 days after the admission, asymptomatic. One year after hospitalization, the patient remains asymptomatic and no rebleeding events or complication have occurred.

(a) Bleeding diverticula in the sigmoid colon; (b) Adrenaline injection around the bleeding diverticula, conditioning mucosal elevation in the diverticular area; (c) endoscopic tattooing was performed to allow the identification of the bleeding diverticula; (d) EBL of the bleeding diverticula.

DB is mostly intermittent and resolves spontaneously; endoscopic diagnosis is usually presumptive, as the bleeding diverticula is not usually identified.2 Early colonoscopy (within 18h after the final hematochezia) was proved to significantly increase the detection rate of identifiable bleeding diverticula (40.5% versus 10.5%, p<0.01).4 Moreover, Mizuki et al. found higher detection rates of colonoscopy with preparation with polyethylene glycol compared to no preparation, though not statistically significant (28.2% versus 12.0%, p=0.11).4 Most series report higher rebleeding rates with endoscopic clipping when compared to EBL and therefore the latter should be used as a first choice for endoscopic hemostasis.3 In most of the reported series, EBL is a safe procedure without important associated complications.3–5 Nagata et al. recently published a series of 108 patients comparing EC versus EBL in colonic diverticular bleeding and found that the risk of rebleeding after 1 year was higher in the EC group (11.5% with EBL versus 37.0% in the clipping group – P Z .018) and, for EBL, more likely to occur if the diverticula was located in the left colon; also no cases of perforation or need for surgery were registered, although one patient experienced diverticulitis one day after EBL.6 In our case, one year after endoscopic band ligation, the patient remains asymptomatic, without record of rebleeding events or complications like diverticulitis or perforation. Also, in a series of 95 patients, Shimamura et al. concluded that EBL can be safely and effectively performed by non-expert endoscopists.5 It is of notice that, in our case, the endoscopist that performed the EBL had never done this procedure before, in the context of colonic DB. In this case, we believe that tattooing the bleeding area was important to identify the correct diverticulum, once the EBL kit was placed. Furthermore, the injection of adrenaline and mucosal elevation in the diverticular area might have facilitated following suction, rubber band placement and eversion of the bleeding diverticula.

In conclusion, this case illustrates that EBL can be an effective and safe procedure to control colonic DB, particularly in patients with comorbidities, avoiding surgery.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.