Actinomycetes are Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria that are part of the usual flora of the gastrointestinal tract, bronchial tree and female genital tract. Despite this, they sometimes act as pathogens. Chronic cervicofacial suppurative infections are common. Disruption of the mucosal barrier may promote penetration of the micro-organism into any organ in the body.1,2 Oesophageal involvement is rare and usually occurs in immunodepressed patients, although it has also been reported in people with no known immunological abnormalities.3 Other predisposing conditions such as alcoholism, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus and chronic pulmonary disease are found in other cases.4

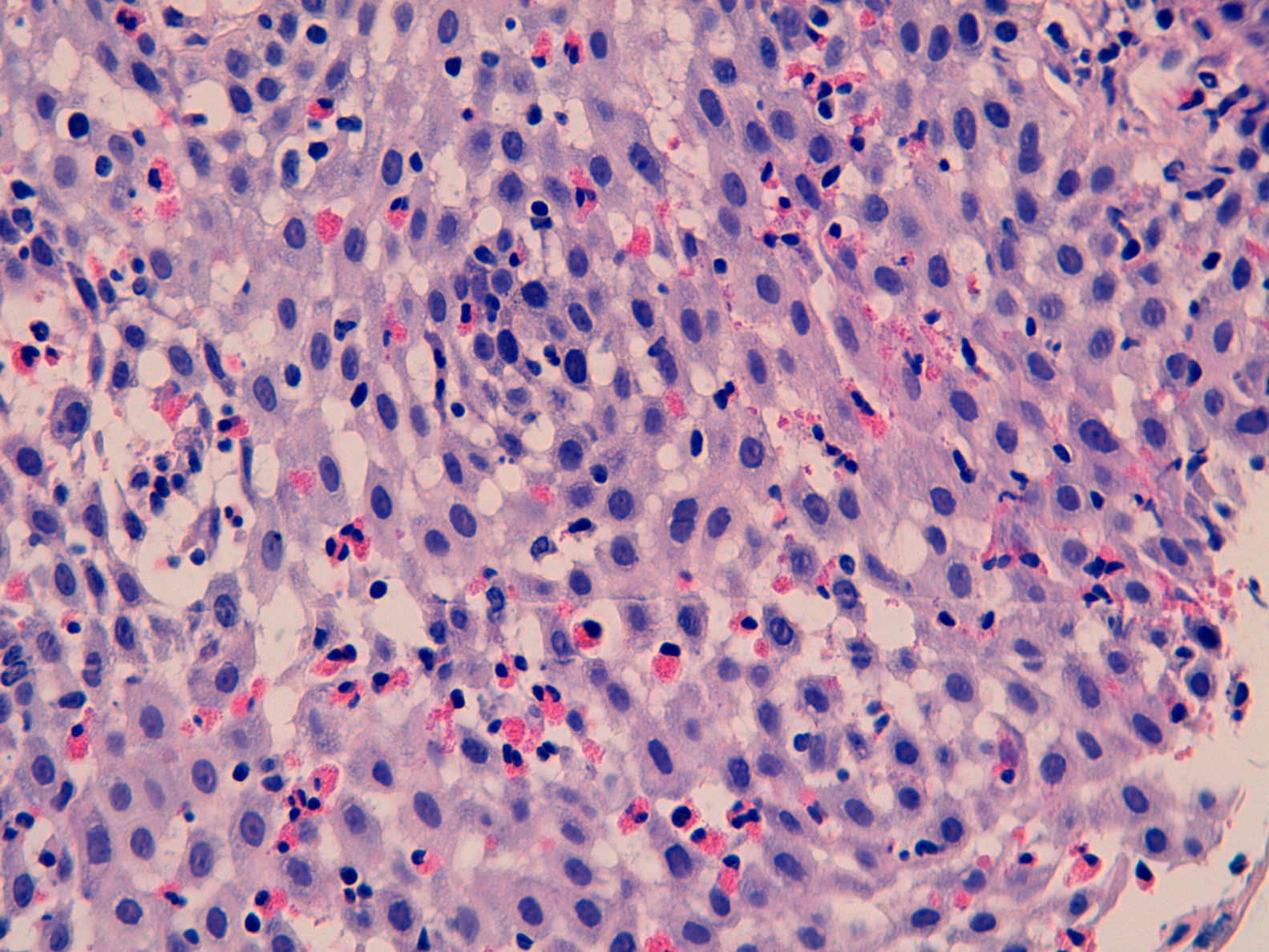

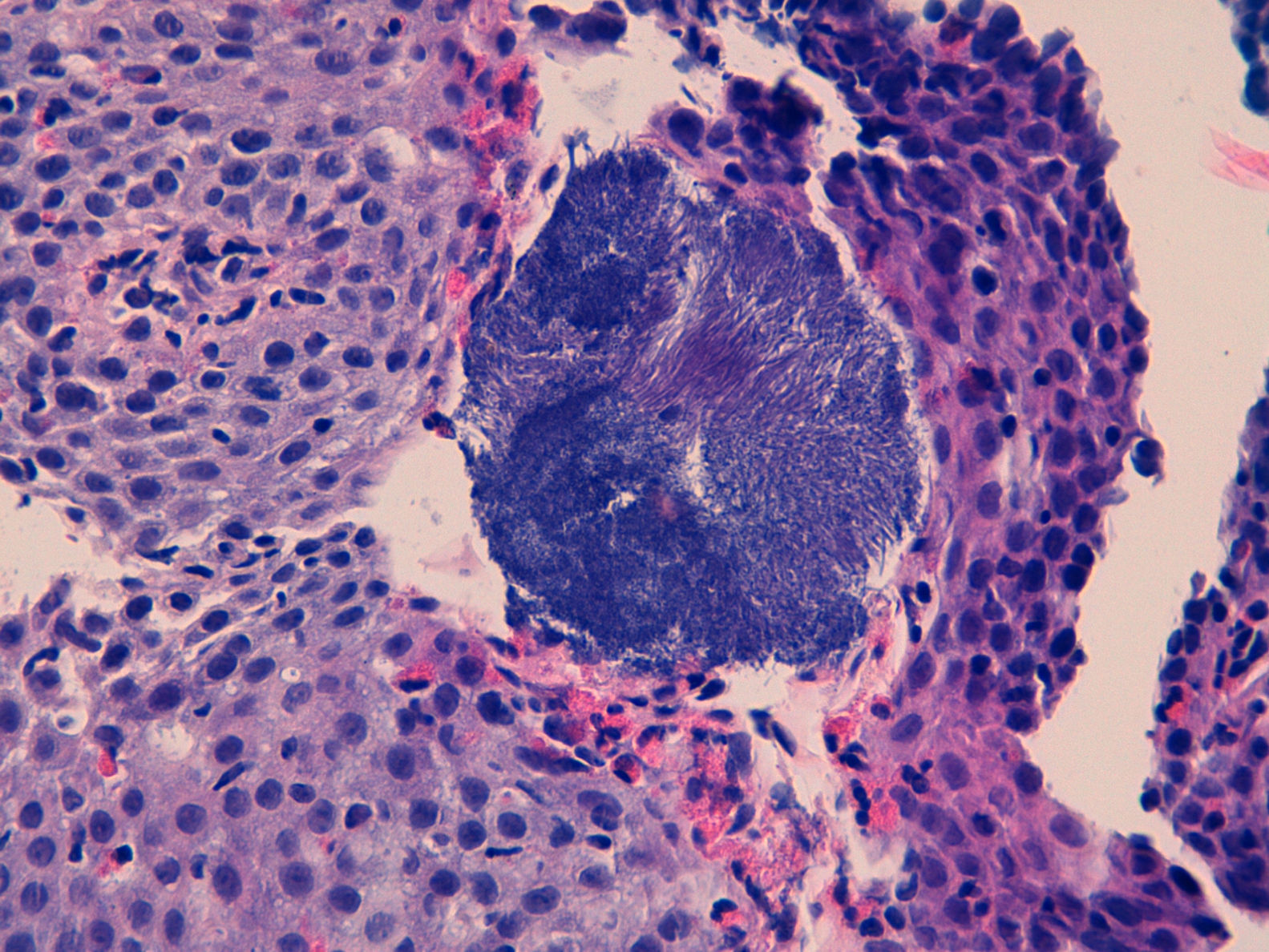

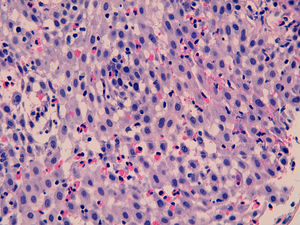

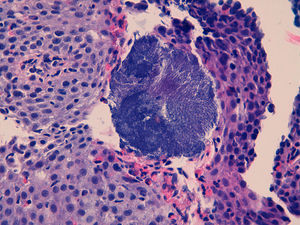

We report the case of a 30-year-old patient assessed due to dysphagia to solids. His history was limited to allergic asthma and hyperuricaemia. He was also an active smoker. In prior years, he had received inhaled budesonide 200–400μg/day for periods of up to 2 consecutive years. This treatment had been discontinued more than 3 years ago. Currently, he only used inhaled terbutaline as needed. He worked in ventilation duct maintenance. His physical examination showed no abnormalities. His laboratory tests did not show any significant abnormalities either. A gastroscopy was performed and revealed thin longitudinal striations, as well as faint rings in the distal third. All this was suggestive of eosinophilic oesophagitis. He also had a small sliding hiatal hernia. Biopsy findings were consistent with eosinophilic oesophagitis (>20 eosinophils per high-power field [Eo/HPF]) in addition to surface colonies of Actinomyces (Figs. 1 and 2). He was treated with doxycycline 100mg/12h for 4 weeks. Immunodeficiencies associated with normal immunoglobulins, complete blood count, antinuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and C3/C4 were ruled out. HIV serology was negative.

Following antibiotic treatment, his signs and symptoms of dysphagia clearly improved, although they did not entirely resolve. In a gastroscopy performed 5 months later, endoscopic signs of eosinophilic oesophagitis persisted with concentric rings and whitish exudate. The biopsy confirmed their presence (>20Eo/HPF) and showed no colonies of Actinomyces. An allergy study revealed only positivity for aeroallergens (mites, grasses, Plantago and cats). It did not detect any food allergies. The patient was treated with omeprazole 20mg/12h for 8 weeks, and a solution of swallowed fluticasone 400μg/12h for one month, which was decreased to 400μg per day for another month. When he failed to respond, he was switched to inhaled fluticasone 500μg/12h for 8 weeks. Histological remission was not confirmed following treatment. Despite clinical improvement with treatment, he had isolated, self-limiting episodes of dysphagia. Consequently, another endoscopic examination was performed a year later. That examination revealed endoscopic signs of eosinophilic oesophagitis (whitish exudate and longitudinal striae). The increased eosinophils (>15Eo/HPF), characteristic of this disorder, persisted on biopsy. When he did not improve, despite treatment with proton pump inhibitors and topical corticosteroids, he started an empirical elimination diet.

We report the first case of oesophageal actinomycosis associated with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Other infections such as candidiasis, mainly following treatment with corticosteroids, and herpes simplex virus infection have been reported in these patients.5,6 Oesophageal actinomycosis is a rare disorder, but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases of infectious oesophagitis. A. israelii is the most common type of infectious oesophagitis in humans, although there are other species (A. naeslundii, A. viscosus, A. odontolyticus and A. bovis).1,2,4 In general, they have a low pathogenic potential, although any mucosal disruption contributes to the development of the infection.1,2 It is commonly found in immunosuppressed patients and patients with neoplastic processes, and rare in immunocompetent patients.3,7 Certain diseases may predispose immunocompetent patients to its development. It has even been postulated that a hiatal hernia may play a role in its pathogenesis.3 The most common signs and symptoms are dysphagia and odynophagia. Progressive deep tissue involvement may be seen on X-ray.8 Imaging studies usually show non-specific findings, although they contribute to detecting associated complications, such as fistulas.8 Diagnosis consists of demonstrating the micro-organism on biopsy or culture. The histology study usually also reveals typical sulphur granules. The culture has low sensitivity and requires a long incubation time in enriched media. The usual empirical treatment consists of penicillin G for a prolonged period. It is also possible to use tetracyclines, erythromycin or clindamycin.

Oesophageal actinomycosis in a patient with eosinophilic oesophagitis had not been reported previously. Not only did it occur in an immunocompetent patient, but also there were no macroscopic mucosal disruptions promoting infection with Actinomyces. However, in active eosinophilic oesophagitis, it is known that there is an abnormality in the epithelial barrier, as well as inflammatory proliferation.9,10 Moreover, the immune and oesophageal motor disorders associated with this disorder may have contributed to superinfection with this micro-organism. Prolonged treatment with corticosteroids may also have altered the oral microbiota and contributed to the proliferation of Actinomyces. However, it is not known whether eosinophilic oesophagitis per se predisposes the patient to a higher risk of local infections. As this is the first report of this association between eosinophilic oesophagitis and oesophageal actinomycosis, clinicians should watch for the onset of new cases to accurately delimit risk factors, whether inherent to the disease or to its treatment with corticosteroids, that may predispose patients to local infection with Actinomyces.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Lago I, Calderón Á, Cazallas J, Camino ME, Barredo I, Cabriada JL. Primer caso clínico de actinomicosis esofágica en un paciente con esofagitis eosinofílica activa. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:404–406.