Ingesting wrapped tablets is an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal bleeding.1–3 The risk groups for this complication would include children, patients with dementia, visual or swallowing conditions, alcoholics and psychiatric patients.1–6 We present a case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after the ingestion of a blister-wrapped tablet in a cirrhotic patient.

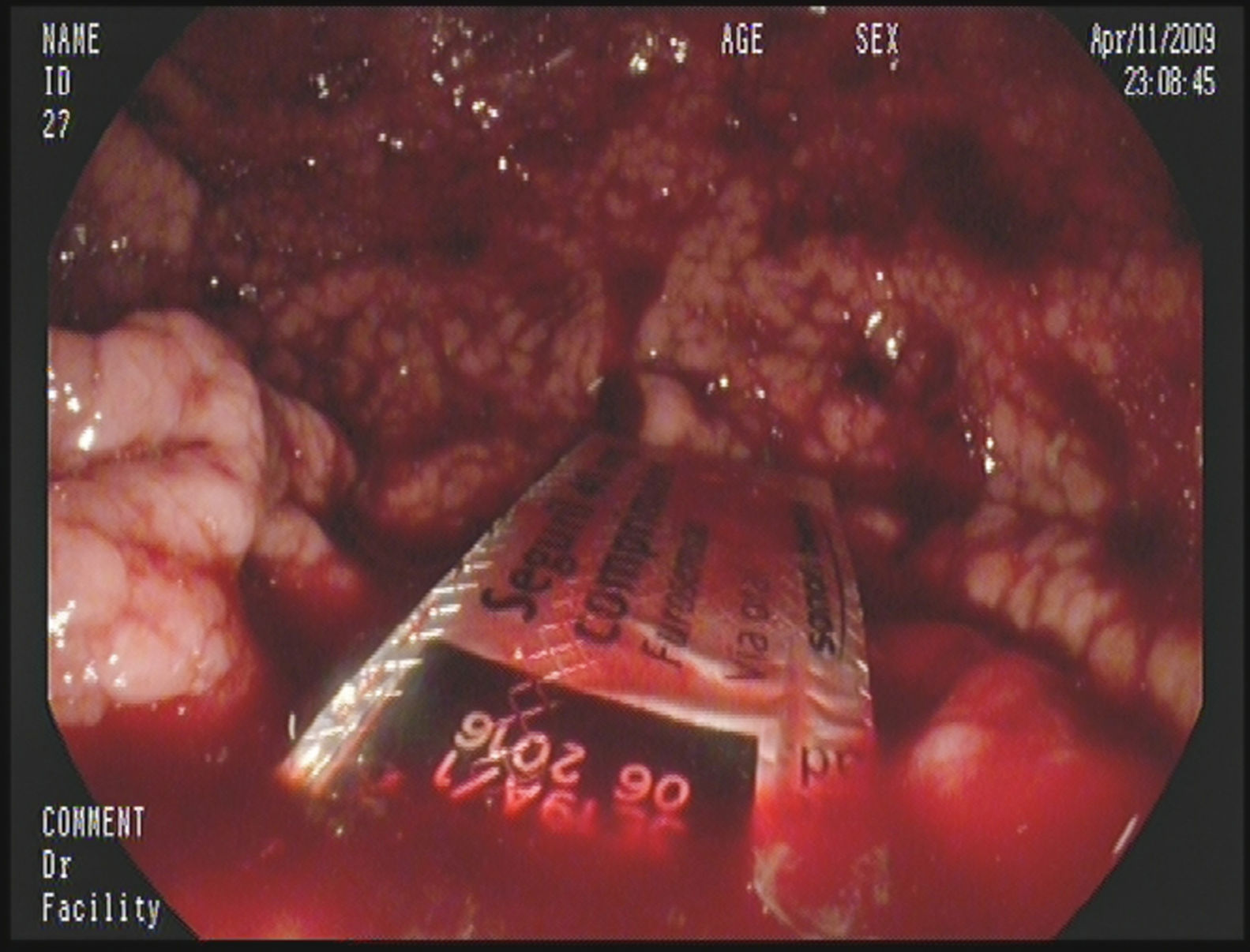

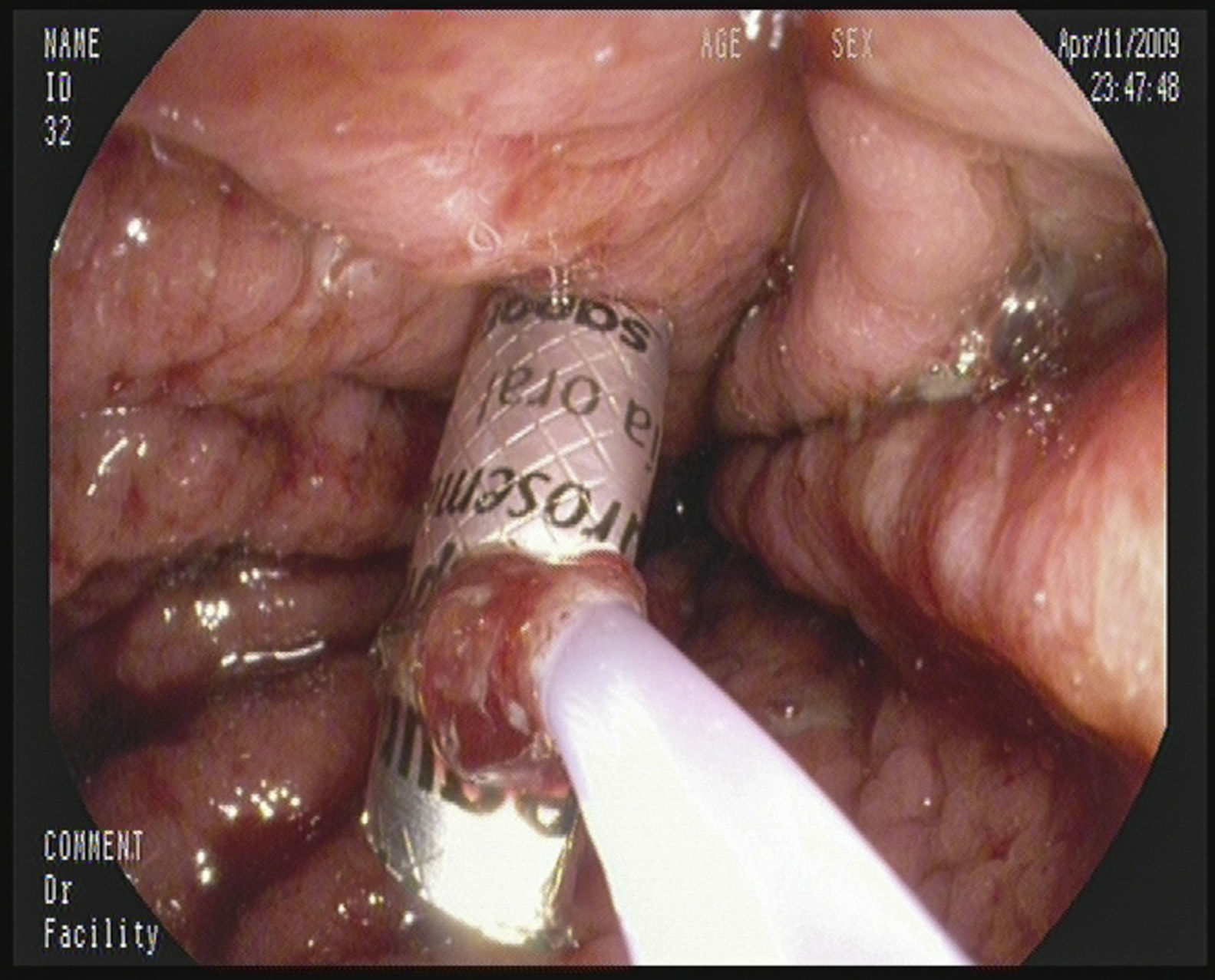

A 45-year-old male with a history of chronic hepatitis C, alcoholism (he consumes more than 140g of ethanol/day) and ex-user of parenteral drugs, who went to the emergency department due to increasing symptoms of the abdominal girth and swelling starting one month prior. On advice from his doctor, he had started treatment with spironolactone and had stopped consuming alcohol in the last 4 days without improvement. Upon physical examination, the following was noted: jaundice, telangiectasia, bilateral parathyroid hypertrophy, signs of ascites, a non-complicated umbilical hernia and pitting oedema in the lower limbs. The urgent blood test found the following: mild anaemia, thrombocytopenia, macrocytosis, total bilirubin 8mg/dl (direct 6.6mg/dl), AST 125IU/L, ALT 72U/L, GGT 152IU/L, albumin 1.6g/dl and Quick time 29s. The chest X-ray and urine sediment were normal. An urgent abdominal ultrasound revealed a liver with a scalloped edge, with no bile duct dilation, splenomegaly and abundant ascites. A diagnostic, evacuating paracentesis was carried out with albumin replacement and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was ruled out. The patient was admitted with the clinical diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis (discriminant function >32) grafted onto a cirrhosis of mixed origin (alcohol and hepatitis C) and fluid retention. Treatment was started with furosemide, spironolactone, thiamine, lactulose and prednisone. On the seventh day in hospital, spatio-temporal disorientation and asterixis was detected, and so anti-encephalopathy measures were prescribed. After 24h, the patient showed symptoms of haematemesis, and so treatment with somatostatin was started and an emergency endoscopy was carried out. The endoscopy showed small oesophageal varices, fresh traces of blood in the stomach, and the presence of a blister pack lodged in the antrum (Fig. 1). After several attempts, the blister pack was able to be folded with a polypectomy snare (Fig. 2) and it was extracted with an overtube. Once it was extracted, the blister pack was checked to see if it contained the furosemide tablet inside. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and after several complications he was discharged.

Blister packs are one of the most commonly used ways to package medicine. They are usually composed of a rigid, plastic, transparent film with several cavities or bubbles (blisters) that contain the tablets covered with a thin sheet of foil. This plastic film is usually perforated which allows each blister to be individually separated. Although, it may sometimes be necessary to cut them with scissors, which increases their hazardousness due to their sharp, angled edges. Once detected within the GI tract, they must be extracted due to the elevated risk of puncture.7 In the case that we present, a cirrhotic patient with severe coagulopathy and oesophageal varices, a successful outcome was possible due to the expertise and experience of the endoscopist.

The progressive ageing of the population, the increased number of dependent people, and the polypharmacy that these factors involve, makes an increase of accidental ingestion cases of wrapped tablets predictable. This complication could happen within the community and during a patient's stay in hospital.4 Although there are methodological variations amongst the different studies carried out, it is estimated that, globally, medication errors occur between 8% and 19% of all of the administered medicines in hospitals.8,9 On the other hand, the real magnitude of this problem may be underestimated given that a large number of mistakes are not reported.10 Approximately one third of these mistakes are made when preparing and administering the medication.8,9 Extracting the tablets from the blister pack before they are dispensed or administered under the supervision of health staff or family members would help to improve patient safety and prevent an accidental ingestion with serious consequences.1–6

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Campos-Franco J, Vallejo-Senra N, Martín Carreras-Presas FL, López-Rodríguez R, Domínguez-Santalla MJ, Alende-Sixto R. Hemorragia digestiva alta por ingestión de un comprimido en blíster. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:18–19.