Approximately 25% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) will develop, either initially or during its evolution, an episode of severe UC.1 Multidisciplinary and protocolised management with an early evaluation (days three to five) of the response to steroids and the use of rescue therapies (infliximab [IFX] and calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus), have led to an improvement in the prognosis of these patients and avoidance of the need for early colectomy.1

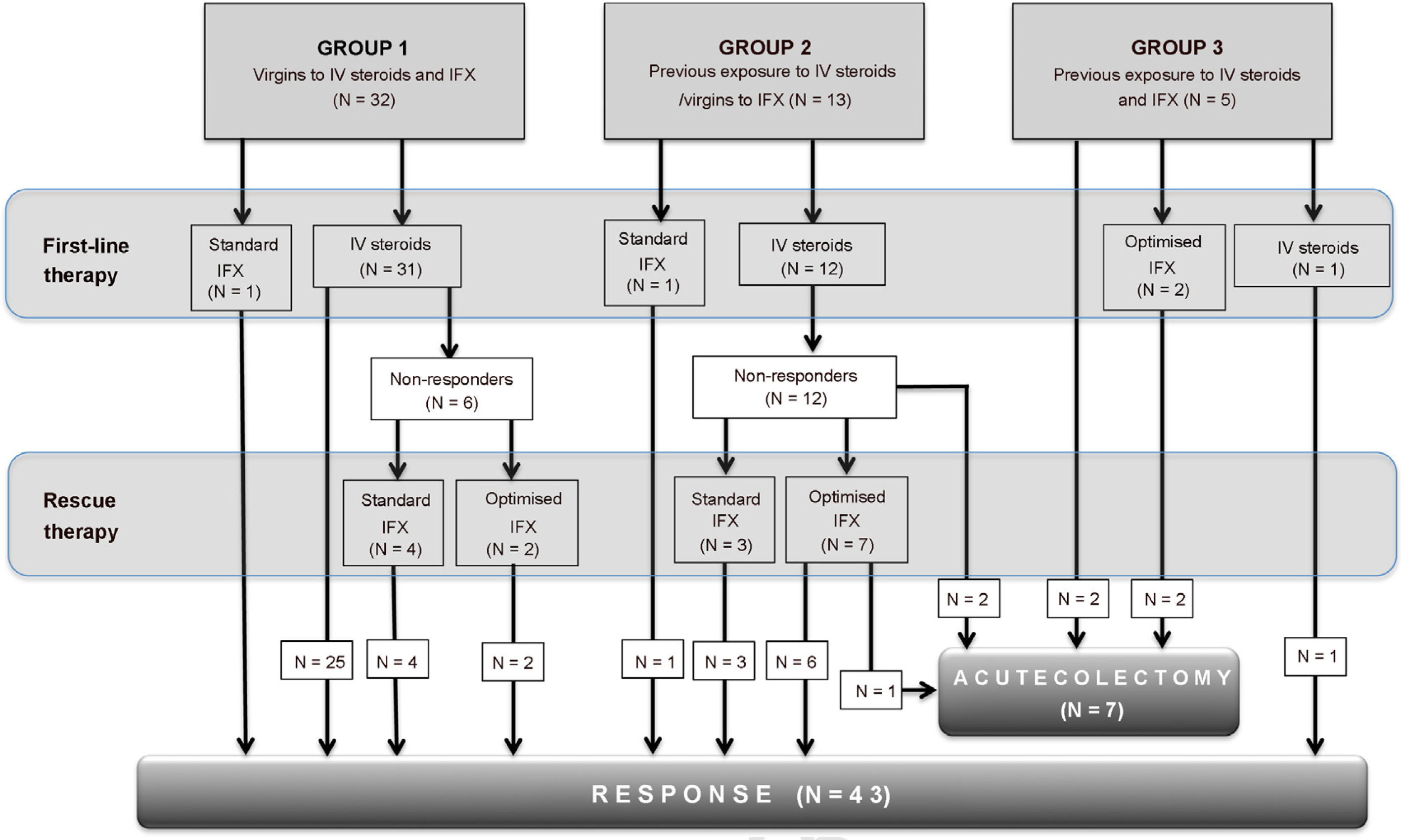

Below we describe the short-term results of multidisciplinary management, through an observational, descriptive and retrospective study of severe UC flare-ups, according to the Truelove and Witts criteria of patients discharged between January 2014 and June 2019. For analysis purposes, the flare-ups were divided into three groups, according to the history of previous treatment with intravenous (IV) steroids and IFX: Group 1: virgins to IV steroids and IFX; Group 2: prior exposure to IV steroids/virgin to IFX; and Group 3: prior exposure to IV steroids and maintenance IFX (Fig. 1). Failure of steroid therapy (corticosteroid-refractoriness) was defined according to the Oxford criteria,1 between the third and fifth days. We carried out a descriptive and association statistical analysis (χ2; P < .05).

Fifty episodes of severe UC were included in 41 patients, 21 were in women (42%) and the median age was 27 years (range 14–64). Six patients had more than one flare-up. In 22% of the episodes, the patients had previous exposure to thiopurines and 14% to anti-TNF (IFX: five, adalimumab: two). Infection by Clostridioides difficile was evaluated in 48 flare-ups (96%), six of which were positive (12.5%). Colonoscopy was performed in 98% of the episodes: 27 and 73% corresponded to an endoscopic Mayo Score of two and three, respectively. Study for cytomegalovirus in biopsies was performed in 58% of the flare-ups, with high-grade infection found in two. All patients were evaluated by a gastroenterologist belonging to the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) programme from admission, and 70% had an evaluation by a coloproctologist specialising in IBD (median 1.5 days; range 1–7) from admission. In addition, nutritional and psychological assessment occurred in 70% and 14% of crises, respectively.

88% of the flare-ups were treated with IV as first-line therapy (median: three days; range: 1–7), with corticosteroid-refractoriness in 41% of them. The IV steroids virgin group (group 1) had a greater response to steroids than those with a history of previous use (group 2) (100 vs. 19%, P < .001). Rescue therapy with IFX was given in 89% of corticosteroid-refractory flare-ups, with a response in 94%. 56% received an optimised induction regimen (intensified, accelerated or intensified/accelerated), with a response rate of 89%. The median hospital stay was seven days and the rate of early colectomy was 14%. No mortality was reported at three months.

The standardisation of the determination of infection by Clostridioides difficile, performance of endoscopy, evaluation of corticosteroid-refractoriness on the third and fifth days and early evaluation by the coloproctologist confirm that a multidisciplinary and protocolised approach is essential for the management of severe UC.1 Although in our study the evaluation of cytomegalovirus infection is greater than that published in the literature,2 this was only 58%, and should be improved.

The response rate to IV steroids was 59%, similar to that reported in the prebiological era.1 However, when breaking down our results, it was significantly lower in patients with previous exposure to IV steroids, but not to IFX, which suggests that, in this group, the start of treatment for a severe flare-up should be directly with IFX. On the other hand, in patients with prior exposure to IV steroids and in the maintenance phase with IFX, the rate of colectomy was high (4/5), suggesting that in this scenario other therapeutic options such as calcineurin inhibitors, followed by a biological agent with a different mechanism of action (vedolizumab), or the use of small molecules could be evaluated.1 Future studies could better define the strategy in this group of patients.

56% of flare-ups received an optimised IFX induction regimen, with a colectomy rate of only 11% at 30 days. These results support the need to intensify and/or accelerate induction doses, given the greater clearance of IFX described in severe UC.3 Although some have not been able to confirm differences between an optimised vs. standard induction,4 a recent publication demonstrated that both intensified and accelerated induction are commonly used strategies in severe UC.5 Randomised prospective studies will allow for the personalisation of treatment in this scenario.

In conclusion, the management of severe UC requires a multidisciplinary and protocolised approach. Our results support the use of clinical guidelines to guide decision-making at the appropriate time.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pérez de Arce E, Quera R, Núñez P, Simian D, Ibáñez P, Lubascher J, et al. Manejo de la colitis ulcerosa aguda grave en Chile: Experiencia de un equipo multidisciplinario. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:206–207.