Symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular colon disease (SUDCD) is a highly prevalent disease in our setting, which significantly affects the quality of life of patients. Recent changes in understanding the natural history of this disease and technological and pharmacological advances have increased the available options for both diagnosis and treatment. However, consensus regarding the use of these options is scarce and sometimes lacks scientific evidence. The objective of this systematic review is to clarify the existing scientific evidence and analyse the use of the different diagnostic and therapeutic options for SUDCD, comparing their advantages and disadvantages, to finally suggest a diagnostic–therapeutic algorithm for this pathology and, at the same time, propose new research questions.

La enfermedad diverticular de colon (EDC) no complicada sintomática (EDCNCS) es una patología con elevada prevalencia en nuestro medio, que afecta de manera importante la calidad de vida de los pacientes que la padecen. Los cambios recientes en la comprensión de la historia natural de esta enfermedad y los avances tecnológicos y farmacológicos han incrementado sustancialmente las opciones disponibles tanto para su diagnóstico, como para el tratamiento. Sin embargo, el consenso que existe en cuanto al uso de estas opciones es pobre y en algunas ocasiones carente de evidencia científica. El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática es esclarecer la evidencia científica existente y fundamentar la utilización de las diferentes opciones diagnósticas y terapéuticas en la EDCNCS, comparando las ventajas y desventajas entre estas, para sugerir finalmente un algoritmo diagnostico-terapéutico para esta patología y al mismo tiempo proponer nuevas preguntas de investigación.

Diverticular disease of the colon (DDC) can be classified as complicated or uncomplicated depending on its clinical presentation.1 Despite a lack of significant clinical complications, uncomplicated DDC may still be symptomatic, manifesting as recurrent or chronic mild abdominal pain, abdominal distension, irregular bowel movements (alternating episodes of diarrhoea and constipation) and/or tenesmus, all caused by the presence of diverticula in the colon.1

Its non-specific symptoms can make it difficult to distinguish from other conditions, yet it significantly affects patients’ quality of life.1 Complicated DDC has been and continues to be studied based on the complications that manifest, and the existing literature supports the different clinical standards and guidelines. For this reason, this review of the literature will focus specifically on symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon (SUDDC).

The prevalence of SUDDC has risen in Western countries over the last 20 years.2–4 In Spain, more than 50% of adults over the age of 50 have diverticular disease (DD).5 The prevalence of DD has been shown to increase with age6, but it is also important to note that incidence among the active population (30–60 years of age) is growing. This entails a risk of complications and may affect the quality of life of these patients.2–4 In total, 10%–25% of people with DD develop complications, such as acute diverticulitis (AD).7 An analysis conducted by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) in the United States between 1998 and 2005 (267,000 admissions) revealed that the incidence of AD-related hospital admissions increased primarily in the 18–44 and 45–64 age ranges, but remained stable in the 65–74 and over-75 age groups.2

The pathophysiology of DD is progressive and goes through several stages associated with the form of clinical presentation (symptoms and presence of complications): (a) development of diverticula; (b) generation of symptoms in uncomplicated DDC; and (c) development of complications, such as AD and other associated conditions.8–12 The aetiology of SUDDC is appears to be multifactorial. Lifestyle is believed to be a key factor in the development of DD and its complications.8 Prospective studies found that a low-fibre diet was associated with DD.9 Genetic factors also play a significant role, attested to by the fact that studies of migratory populations found no changes in the incidence of DD despite these populations adopting new habits.9 Although the pathogenesis of SUDDC is not fully understood, dysbiosis and microscopic inflammation seem to play an important role.10 Moreover, it has been postulated that it may be related to an interaction between colonic microbiota alterations, and immune, enteric nerve and muscular system dysfunction.11 Up to 20% of people with diverticula-associated abdominal pain also have abnormal motor function and a reduced visceral sensitivity threshold.11 An increase in the number of mast cells in all layers of the colon wall can also contribute to the onset of pain.12 The results of a cohort study of more than 9116 patients suggested that a vitamin D (25-OH) deficiency could increase the risk of complicated AD. The risk of AD was found to decrease with levels of 25–30 ng/mL, and to fall yet further with levels in excess of 30 ng/mL.13 In short, although the pathogenesis of SUDDC is believed to be multifactorial, it is not yet fully understood. As a result, there is no established consensus on the diagnosis, follow-up or treatment of patients with uncomplicated DDC, which is reflected by the wide variety of requested complementary tests, symptomatic treatments prescribed and follow-up seen in clinical practice.

Our objective is to systematically review the literature to make sense of the existing scientific evidence and to justify the use of different diagnostic and therapeutic options in SUDDC by comparing their respective benefits and drawbacks. Based on the above, a diagnostic–therapeutic algorithm for this disease will be drawn up and new working hypotheses and research questions proposed.

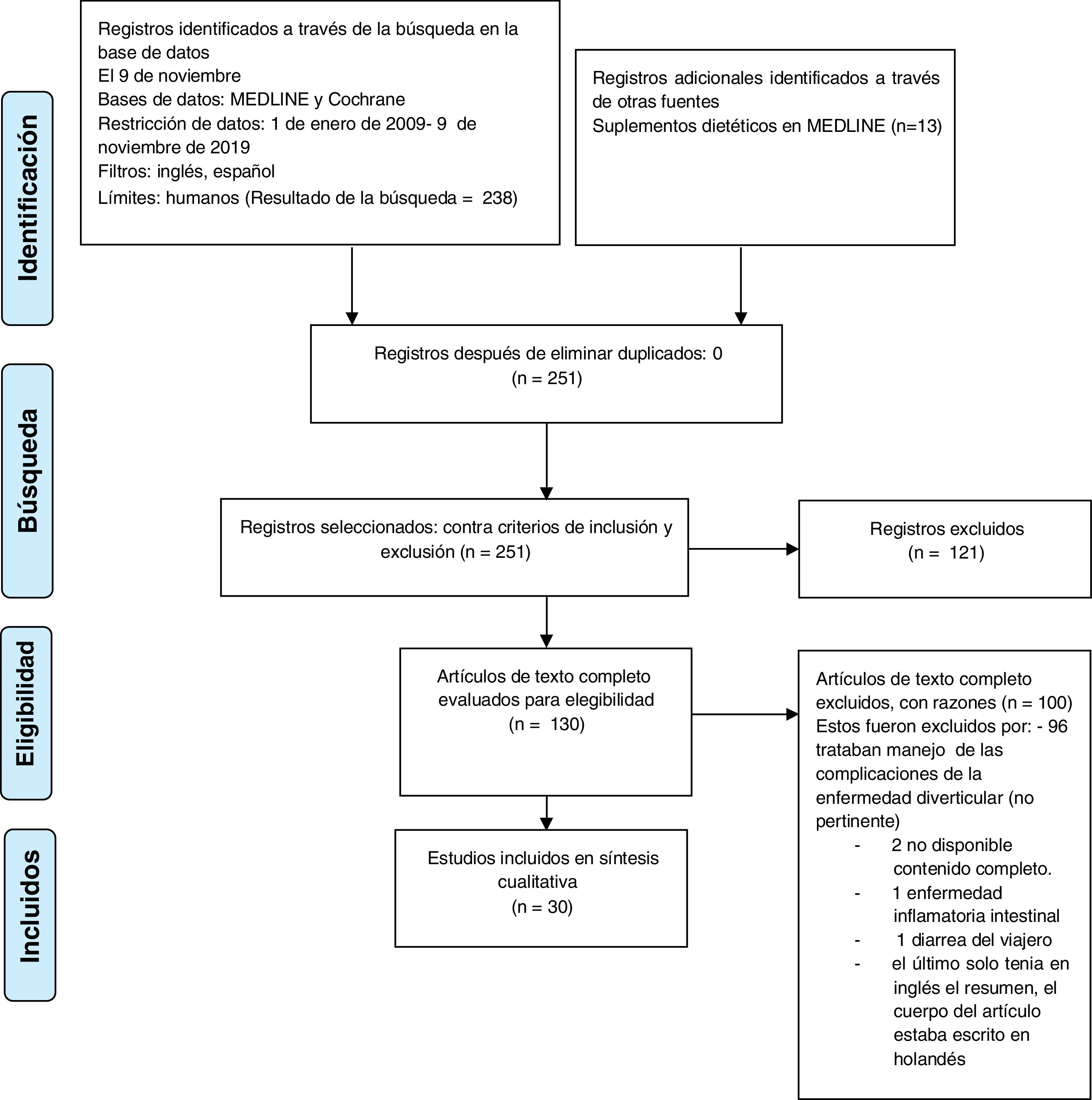

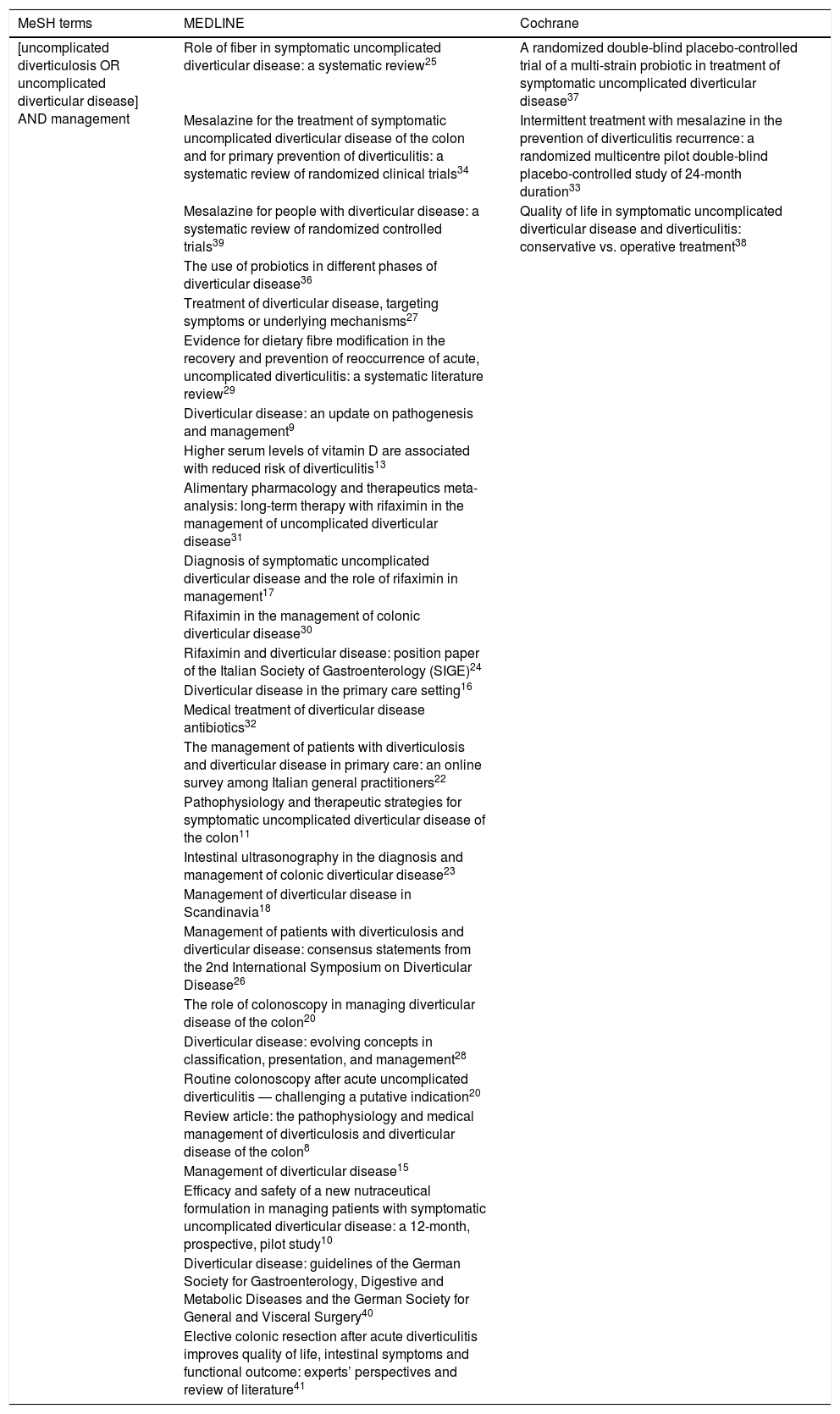

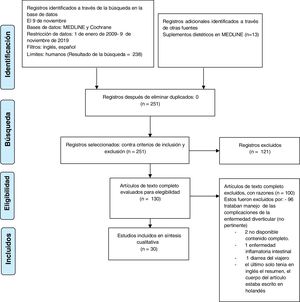

MethodsSearch strategyA systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA protocol. The relevant literature up to December 2019 was selected from the MEDLINE and Cochrane databases by searching for the keywords that included the following MeSH terminology: “uncomplicated diverticular disease” or “uncomplicated diverticulosis”, together with the term “management”. A parallel search was performed using the Dietary supplements section to complete the search in MEDLINE. The complementary keywords used were: “treatment” and “follow up” (Table 1).

Database search by MeSH terminology used.

| MeSH terms | MEDLINE | Cochrane |

|---|---|---|

| [uncomplicated diverticulosis OR uncomplicated diverticular disease] AND management | Role of fiber in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a systematic review25 | A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease37 |

| Mesalazine for the treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon and for primary prevention of diverticulitis: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials34 | Intermittent treatment with mesalazine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence: a randomized multicentre pilot double-blind placebo-controlled study of 24-month duration33 | |

| Mesalazine for people with diverticular disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials39 | Quality of life in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and diverticulitis: conservative vs. operative treatment38 | |

| The use of probiotics in different phases of diverticular disease36 | ||

| Treatment of diverticular disease, targeting symptoms or underlying mechanisms27 | ||

| Evidence for dietary fibre modification in the recovery and prevention of reoccurrence of acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis: a systematic literature review29 | ||

| Diverticular disease: an update on pathogenesis and management9 | ||

| Higher serum levels of vitamin D are associated with reduced risk of diverticulitis13 | ||

| Alimentary pharmacology and therapeutics meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease31 | ||

| Diagnosis of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and the role of rifaximin in management17 | ||

| Rifaximin in the management of colonic diverticular disease30 | ||

| Rifaximin and diverticular disease: position paper of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE)24 | ||

| Diverticular disease in the primary care setting16 | ||

| Medical treatment of diverticular disease antibiotics32 | ||

| The management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease in primary care: an online survey among Italian general practitioners22 | ||

| Pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies for symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon11 | ||

| Intestinal ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of colonic diverticular disease23 | ||

| Management of diverticular disease in Scandinavia18 | ||

| Management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease: consensus statements from the 2nd International Symposium on Diverticular Disease26 | ||

| The role of colonoscopy in managing diverticular disease of the colon20 | ||

| Diverticular disease: evolving concepts in classification, presentation, and management28 | ||

| Routine colonoscopy after acute uncomplicated diverticulitis — challenging a putative indication20 | ||

| Review article: the pathophysiology and medical management of diverticulosis and diverticular disease of the colon8 | ||

| Management of diverticular disease15 | ||

| Efficacy and safety of a new nutraceutical formulation in managing patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a 12-month, prospective, pilot study10 | ||

| Diverticular disease: guidelines of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery40 | ||

| Elective colonic resection after acute diverticulitis improves quality of life, intestinal symptoms and functional outcome: experts’ perspectives and review of literature41 |

The inclusion criteria were: studies published between 1 January 2009 and 8 November 2019, in English or Spanish, in humans, containing at least one of the aforementioned keywords and with a level of evidence between I and IV.14 Duplicates were removed and articles based on data collected prior to 2009 were excluded.

The results were displayed in tables in accordance with their recommendations and level of scientific evidence.

ResultsThe initial search in MEDLINE and the Cochrane library with the aforementioned keywords generated 251 potential articles (238 in MEDLINE, 4 in Cochrane and 13 in MEDLINE’s Dietary supplements section). After restricting the search to virtual libraries and applying the inclusion criteria, 130 preliminary articles were sourced (127 in MEDLINE and 3 in Cochrane).

After manually assessing the full text of these 130 articles against the inclusion criteria, 30 articles (27 in MEDLINE and 3 in Cochrane) were considered the primary references (Fig. 1).

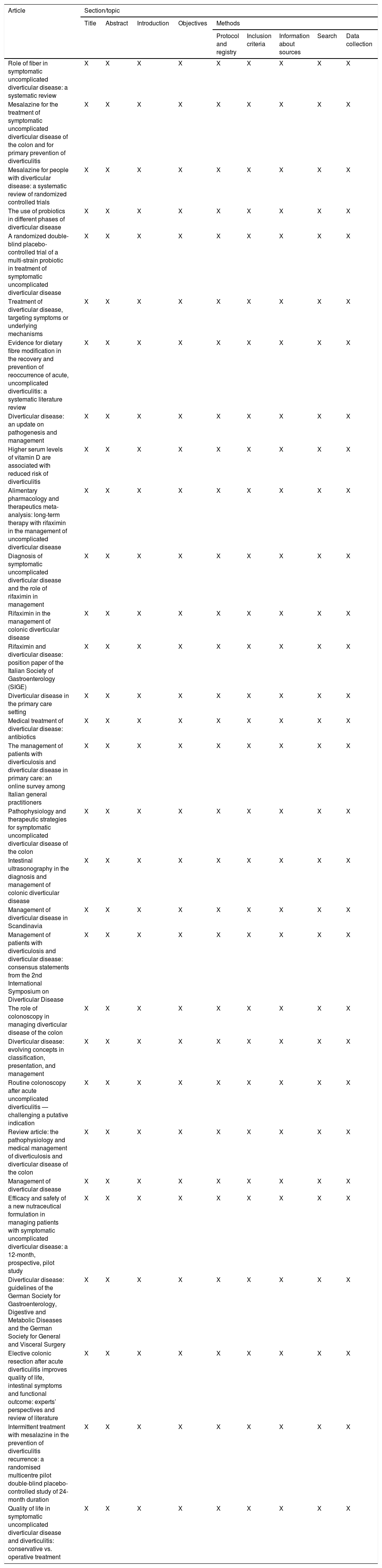

The 30 articles included two meta-analyses, three multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled clinical trials, three analytical, observational prospective studies, two prospective cohort studies, one retrospective cohort study, five systematic reviews, one clinical guideline, two expert consensus statements and 11 reviews (Tables 2 and 3).

Checklist of the selection of relevant reviewed articles as per the PRISMA protocol.

| Article | Section/topic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Abstract | Introduction | Objectives | Methods | |||||

| Protocol and registry | Inclusion criteria | Information about sources | Search | Data collection | |||||

| Role of fiber in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a systematic review | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Mesalazine for the treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon and for primary prevention of diverticulitis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Mesalazine for people with diverticular disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| The use of probiotics in different phases of diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Treatment of diverticular disease, targeting symptoms or underlying mechanisms | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Evidence for dietary fibre modification in the recovery and prevention of reoccurrence of acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis: a systematic literature review | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Diverticular disease: an update on pathogenesis and management | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Higher serum levels of vitamin D are associated with reduced risk of diverticulitis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Alimentary pharmacology and therapeutics meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Diagnosis of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and the role of rifaximin in management | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Rifaximin in the management of colonic diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Rifaximin and diverticular disease: position paper of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Diverticular disease in the primary care setting | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Medical treatment of diverticular disease: antibiotics | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| The management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease in primary care: an online survey among Italian general practitioners | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies for symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Intestinal ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of colonic diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Management of diverticular disease in Scandinavia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease: consensus statements from the 2nd International Symposium on Diverticular Disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| The role of colonoscopy in managing diverticular disease of the colon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Diverticular disease: evolving concepts in classification, presentation, and management | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Routine colonoscopy after acute uncomplicated diverticulitis — challenging a putative indication | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Review article: the pathophysiology and medical management of diverticulosis and diverticular disease of the colon | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Management of diverticular disease | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Efficacy and safety of a new nutraceutical formulation in managing patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a 12-month, prospective, pilot study | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Diverticular disease: guidelines of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Elective colonic resection after acute diverticulitis improves quality of life, intestinal symptoms and functional outcome: experts’ perspectives and review of literature | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Intermittent treatment with mesalazine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence: a randomised multicentre pilot double-blind placebo-controlled study of 24-month duration | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Quality of life in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and diverticulitis: conservative vs. operative treatment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

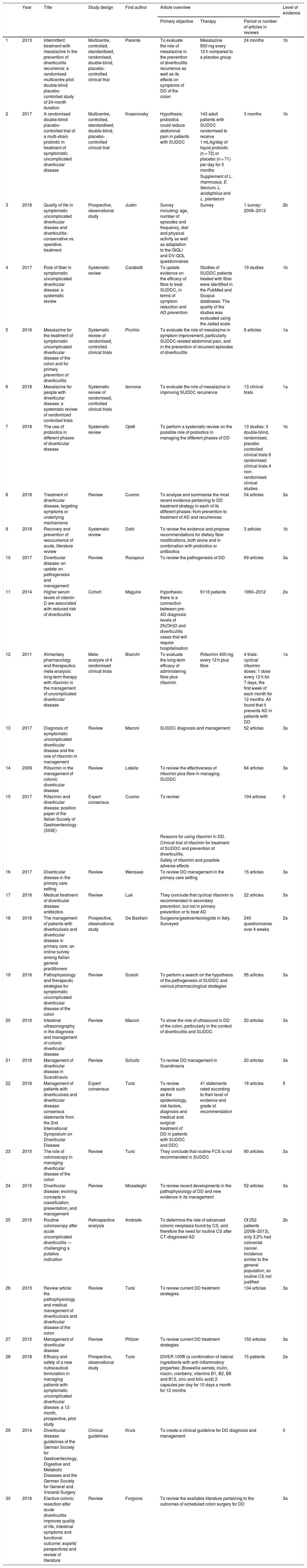

Description of the articles selected.

| Year | Title | Study design | First author | Article overview | Level of evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary objective | Therapy | Period or number of articles in reviews | ||||||

| 1 | 2013 | Intermittent treatment with mesalazine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence: a randomised multicentre pilot double-blind placebo-controlled study of 24-month duration | Multicentre, controlled, standardised, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Parente | To evaluate the role of mesalazine in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence as well as its effects on symptoms of DD of the colon | Mesalazine 800 mg every 12 h compared to a placebo group | 24 months | 1b |

| 2 | 2017 | A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease | Multicentre, controlled, standardised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Kvasnovsky | Hypothesis: probiotics could reduce abdominal pain in patients with SUDDC | 143 adult patients with SUDDC randomised to receive 1 mL/kg/day of liquid probiotic (n = 72) or placebo (n = 71) per day for 3 months | 3 months | 1b |

| Supplement of L. rhamnosus, E. faecium, L. acidophilus and L. plantarum | ||||||||

| 3 | 2016 | Quality of life in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and diverticulitis: conservative vs. operative treatment | Prospective, observational study | Justin | Survey including: age, number of episodes and frequency, diet and physical activity as well as adaptation to the GIQLI and DV-QOL questionnaires | Survey | 1 survey: 2008–2013 | 2b |

| 4 | 2017 | Role of fiber in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a systematic review | Systematic review | Carabotti | To update evidence on the efficacy of fibre to treat SUDDC, in terms of symptom reduction and AD prevention | Studies of SUDDC patients treated with fibre were identified in the PubMed and Scopus databases. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Jadad scale | 19 studies | 1b |

| 5 | 2016 | Mesalazine for the treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon and for primary prevention of diverticulitis | Systematic review of randomised, controlled clinical trials | Picchio | To evaluate the role of mesalazine in symptom improvement, particularly SUDDC-related abdominal pain, and in the prevention of recurrent episodes of diverticulitis | 6 articles | 1a | |

| 6 | 2018 | Mesalazine for people with diverticular disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials | Systematic review of randomised, controlled clinical trials | Iannone | To evaluate the role of mesalazine in improving SUDDC recurrence | 13 clinical trials | 1a | |

| 7 | 2018 | The use of probiotics in different phases of diverticular disease | Systematic review | Ojetti | To perform a systematic review on the possible role of probiotics in managing the different phases of DD | 13 studies: 3 double-blind, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trials 6 randomised clinical trials 4 non-randomised clinical studies | 1b | |

| 8 | 2018 | Treatment of diverticular disease, targeting symptoms or underlying mechanisms | Review | Cuomo | To analyse and summarise the most recent evidence pertaining to DD treatment strategy in each of its different phases: from prevention to treatment of AD and recurrences | 54 articles | 3a | |

| 9 | 2018 | Recovery and prevention of reoccurrence of acute, literature review | Systematic review | Dahl | To review the evidence and propose recommendations for dietary fibre modifications, both alone and in combination with probiotics or antibiotics | 3 articles | 1b | |

| 10 | 2017 | Diverticular disease: an update on pathogenesis and management | Review | Rezapour | To review the pathogenesis of DD | 69 articles | 3a | |

| 11 | 2014 | Higher serum levels of vitamin D are associated with reduced risk of diverticulitis | Cohort | Maguire | Hypothesis: there is a connection between pre-AD diagnosis levels of 25(OH)D and diverticulitis cases that will require hospitalisation | 9116 patients | 1993–2012 | 2a |

| 12 | 2011 | Alimentary pharmacology and therapeutics meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease | Meta-analysis of 4 randomised clinical trials | Bianchi | To evaluate the long-term efficacy of administering fibre plus rifaximin | Rifaximin 400 mg every 12 h plus fibre | 4 trials: cyclical rifaximin doses: 1 dose every 12 h for 7 days, the first week of each month for 12 months. All found that it prevents AD in patients with DD | 1a |

| 13 | 2017 | Diagnosis of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and the role of rifaximin in management | Review | Maconi | SUDDC diagnosis and management | 52 articles | 3a | |

| 14 | 2009 | Rifaximin in the management of colonic diverticular disease | Review | Latella | To review the effectiveness of rifaximin plus fibre in managing SUDDC | 84 articles | 3a | |

| 15 | 2017 | Rifaximin and diverticular disease: position paper of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) | Expert consensus | Cuomo | To review: | 104 articles | 5 | |

| Reasons for using rifaximin in DD. | ||||||||

| Clinical trial of rifaximin for treatment of SUDDC and prevention of diverticulitis. | ||||||||

| Safety of rifaximin and possible adverse effects | ||||||||

| 16 | 2017 | Diverticular disease in the primary care setting | Review | Wensaas | To review DD management in the primary care setting | 15 articles | 3a | |

| 17 | 2016 | Medical treatment of diverticular disease: antibiotics | Review | Lué | They conclude that cyclical rifaximin is recommended in secondary prevention, but not in primary prevention or to treat AD | 22 articles | 3a | |

| 18 | 2016 | The management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease in primary care: an online survey among Italian general practitioners | Prospective, observational study | De Bastiani | Surgeons/gastroenterologists in Italy. Surveyed | 245 questionnaires over 4 weeks | 2a | |

| 19 | 2016 | Pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies for symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon | Review | Scaioli | To perform a search on the hypothesis of the pathogenesis of SUDDC and various pharmacological strategies | 95 articles | 3a | |

| 20 | 2016 | Intestinal ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of colonic diverticular disease | Review | Maconi | To show the role of ultrasound in DD of the colon, particularly in the context of diverticulitis and SUDDC | 20 articles | 3a | |

| 21 | 2016 | Management of diverticular disease in Scandinavia | Review | Schultz | To review DD management in Scandinavia | 20 articles | 3a | |

| 22 | 2016 | Management of patients with diverticulosis and diverticular disease: consensus statements from the 2nd International Symposium on Diverticular Disease | Expert consensus | Tursi | To review aspects such as the epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and medical and surgical treatment of DD in patients with SUDDC and DDC | 41 statements rated according to their level of evidence and grade of recommendation | 18 articles | 5 |

| 23 | 2015 | The role of colonoscopy in managing diverticular disease of the colon | Review | Tursi | They conclude that routine FCS is not recommended in SUDDC | 90 articles | 3a | |

| 24 | 2015 | Diverticular disease: evolving concepts in classification, presentation, and management | Review | Mosadeghi | To review recent developments in the pathophysiology of DD and new evidence in its management | 52 articles | 3a | |

| 25 | 2015 | Routine colonoscopy after acute uncomplicated diverticulitis — challenging a putative indication | Retrospective analysis | Andrade | To determine the rate of advanced colonic neoplasia found by CS, and therefore the need for routine CS after CT-diagnosed AD | Of 252 patients (2008–2013), only 3.2% had colorectal cancer. Incidence similar to the general population, so routine CS not justified | 2b | |

| 26 | 2015 | Review article: the pathophysiology and medical management of diverticulosis and diverticular disease of the colon | Review | Tursi | To review current DD treatment strategies | 134 articles | 3a | |

| 27 | 2015 | Management of diverticular disease | Review | Pfützer | To review current DD treatment strategies | 150 articles | 3a | |

| 28 | 2018 | Efficacy and safety of a new nutraceutical formulation in managing patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a 12-month, prospective, pilot study | Prospective, observational study | Tursi | DIVER 100® (a combination of natural ingredients with anti-inflammatory properties: Boswellia serrata, inulin, niacin, cranberry, vitamins B1, B2, B6 and B12, zinc and folic acid) 2 capsules per day for 10 days a month for 12 months | 15 patients | 2a | |

| 29 | 2014 | Diverticular disease: guidelines of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery | Clinical guidelines | Kruis | To create a clinical guideline for DD diagnosis and management | 5 | ||

| 30 | 2016 | Elective colonic resection after acute diverticulitis improves quality of life, intestinal symptoms and functional outcome: experts’ perspectives and review of literature | Review | Forgione | To review the available literature pertaining to the outcomes of scheduled colon surgery for DD | 3a | ||

AD: acute diverticulitis; CS: colonoscopy; CT: Clinical trial; DD: diverticular disease; SUDDC: symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon.

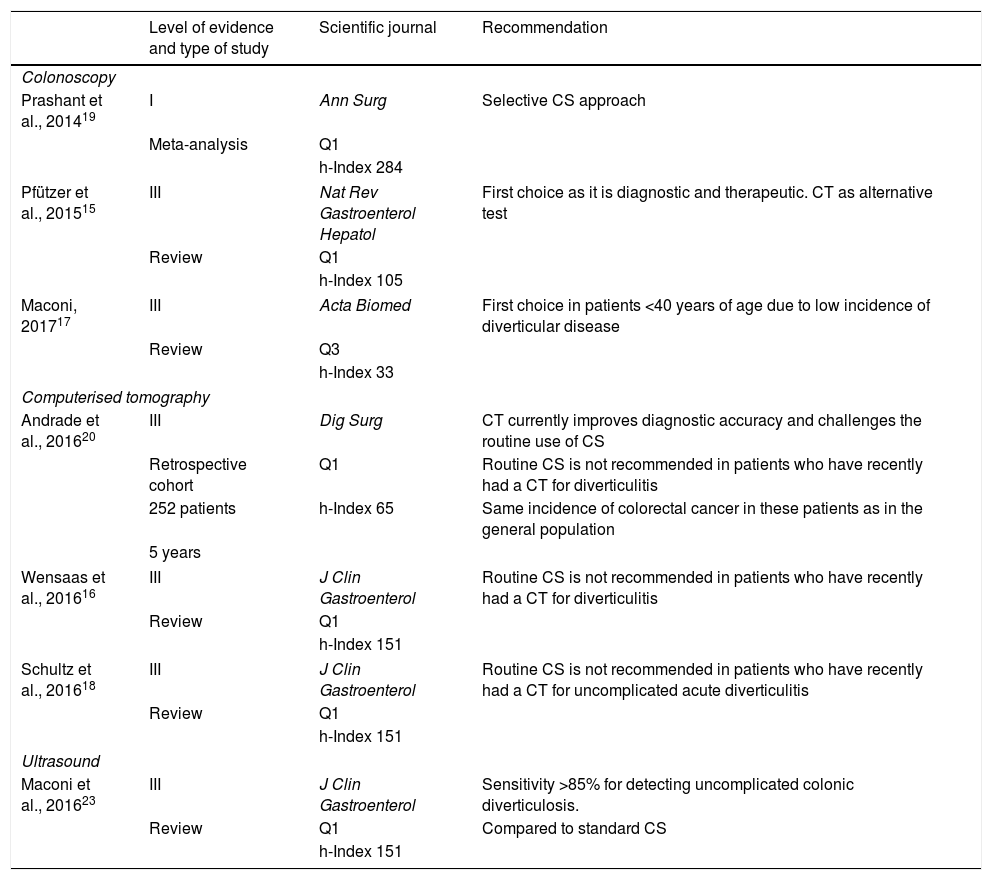

The most accurate diagnostic tests for DD are colonoscopy (CS) and computed tomographic colonography (CTC). The choice of one over the other depends on patient preference, age, clinical status and colorectal cancer risk factors. Double-contrast barium enema is only an option if CTC is not available.

ColonoscopyBoth CS and CTC offer all the benefits of a diagnostic–therapeutic test, but CS carries a higher risk of complications, such as perforation and haemorrhage.15 Routine CS is not recommended in primary care for patients with a recent history of AD (<1 month).16 CS could be the option of choice in young patients (≤40 years) with a low prevalence of DD and a greater risk of inflammatory bowel disease.17 Routine CS is not recommended in Scandinavia as it is assumed that patients with an episode of AD have already undergone computerised tomography (CT).18 According to international clinical guidelines and best practice, CS has until now been considered the diagnostic test of choice after an episode of AD to confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancy. However, the routine use of CS after an episode of AD is disputed.19 Although there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that patients with DDC are at greater risk of cancer, the overlapping characteristics of diverticulitis and colon cancer have historically made a differential diagnosis extremely difficult. As a result, it is only recommended to perform a CS after conservatively treating AD. Despite this, contradictory evidence has been published in recent years that promotes a more selective approach.19 Andrade et al.20 conducted a retrospective analysis between 2008 and 2013 to determine the rate of advanced colonic neoplasia identified by CS and the need to perform a routine CS after an episode of CT-diagnosed AD. Of the 252 patients included, colorectal cancer was detected by CS in 3.2%. Given that these findings were similar to the prevalence among the general population, it was concluded that routine CS after AD should not be recommended (Table 4).21

Diagnostic tests for SUDDC, publication recommendations ordered by level of scientific evidence.

| Level of evidence and type of study | Scientific journal | Recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy | |||

| Prashant et al., 201419 | I | Ann Surg | Selective CS approach |

| Meta-analysis | Q1 | ||

| h-Index 284 | |||

| Pfützer et al., 201515 | III | Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol | First choice as it is diagnostic and therapeutic. CT as alternative test |

| Review | Q1 | ||

| h-Index 105 | |||

| Maconi, 201717 | III | Acta Biomed | First choice in patients <40 years of age due to low incidence of diverticular disease |

| Review | Q3 | ||

| h-Index 33 | |||

| Computerised tomography | |||

| Andrade et al., 201620 | III | Dig Surg | CT currently improves diagnostic accuracy and challenges the routine use of CS |

| Retrospective cohort | Q1 | Routine CS is not recommended in patients who have recently had a CT for diverticulitis | |

| 252 patients | h-Index 65 | Same incidence of colorectal cancer in these patients as in the general population | |

| 5 years | |||

| Wensaas et al., 201616 | III | J Clin Gastroenterol | Routine CS is not recommended in patients who have recently had a CT for diverticulitis |

| Review | Q1 | ||

| h-Index 151 | |||

| Schultz et al., 201618 | III | J Clin Gastroenterol | Routine CS is not recommended in patients who have recently had a CT for uncomplicated acute diverticulitis |

| Review | Q1 | ||

| h-Index 151 | |||

| Ultrasound | |||

| Maconi et al., 201623 | III | J Clin Gastroenterol | Sensitivity >85% for detecting uncomplicated colonic diverticulosis. |

| Review | Q1 | Compared to standard CS | |

| h-Index 151 | |||

Given that CTC offers greater diagnostic accuracy, a lower rate of complications and is less invasive than CS, it may be the test of choice in elderly and frail patients, and/or in patients with potential contraindications for CS and sedation.17 However, indicating this test is dependent on the availability of high-resolution, multislice, helical CT with image reconstruction and, most importantly, radiologists trained to interpret them. The arrival of high-resolution CT has improved diagnostic accuracy and has challenged the requirement for a routine CS after CT-diagnosed AD.20 Despite this, according to a prospective study conducted in Italy by a group led by Bastiani et al.22, CS continues to be the first diagnostic test requested by most physicians (77%) (Table 4).

Abdominal ultrasoundA non-inflamed diverticular wall cannot usually be detected by ultrasound. However, the muscularis propria of the wall of the colon is often found to be hypertrophic, which can be a sign of diverticula. A prospective study that used CS as the reference standard found that its sensitivity and specificity for detecting uncomplicated colonic diverticulosis were greater than 85% (Table 4).23

Biochemical markersNon-specific markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (protein produced by neutrophils) increase in the event of intestinal inflammation. Faecal calprotectin significantly increases in inflammatory bowel disease, but it can also increase in symptomatic uncomplicated DD, raising the need for a differential diagnosis.17 It is negative in irritable bowel syndrome.17 However, absolute cut-off values for these markers in SUDDC have not yet been established. A prospective study of physicians found that 77% request laboratory tests as part of DDC patient follow-up, but only 14% include faecal calprotectin.22

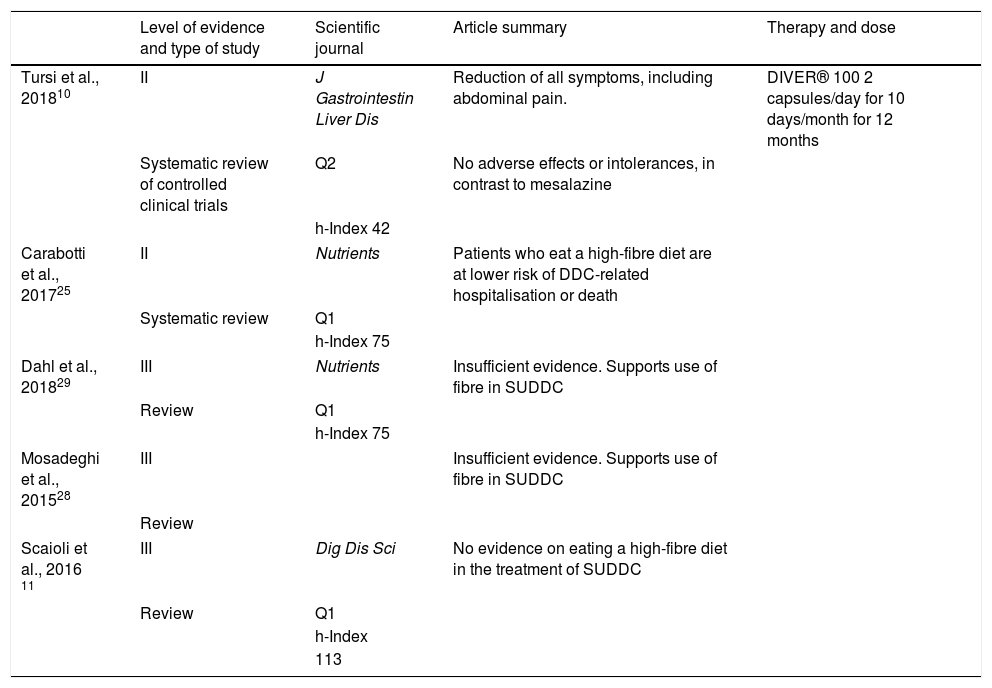

TreatmentThe first-line treatment for DDC should not be pharmacological.24 A high-fibre diet is recommended for these patients. Patients who eat a high-fibre diet have a lower risk of DDC-related hospital admission or death. This effect is attributed to the high intake of insoluble fibre.25 However, there is no standard treatment for SUDDC. As well as making changes in hygiene and dietary habits, it can also be treated in combination with non-absorbable antibiotics, anti-inflammatories or probiotics.26 Although DDC does not require a specific therapy, the treatment of SUDDC is based on combinations of different options. All of the above underlines the lack of progress made in terms of primary prevention, and that, in managing secondary prevention, there is currently insufficient evidence to endorse a specific strategy, considering the healthcare costs of recurrences.27

DietA systematic review of 19 manuscripts published in 2017 by Carabotti et al.25 provided an update on the effect of fibre (both dietary and from supplements). Despite seeming to be beneficial, the role of fibre in SUDDC symptom control and its effect on recurrences could not be determined due to the poor scientific quality of articles and studies published to date.28 A high-fibre diet has been defined as the intake of at least 30 g of fibre per day. However, with regard to fibre supplements, a meta-analysis on the merits of this treatment could not be conducted due to the heterogeneity of the manuscripts reviewed. As such, no specific dosage could be recommended. It was also not possible to recommend soluble fibre over insoluble fibre, or vice versa, for the same reasons.25 The recent systematic review by Mosadeghi et al.28 is based on three studies that modified dietary fibre intake after an episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis and that recorded gastrointestinal symptoms and recurrences, each without a control group.29 It concluded that evidence in support of a diet high in dietary fibre and/or dietary fibre supplements, for both recurrence prevention and gastrointestinal symptom improvement, was of poor quality. Although there seems to be little consensus on the role that a low-fibre diet plays in the development of DDC, increasing fibre intake is nevertheless likely to have some benefit in reducing the complications of DDC. That is why the latest guidelines issued by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) on DDC openly recommend high dietary fibre intake in patients with a history of AD (Table 5).9

High-fibre diet and/or diet with fibre supplements in SUDDC, publication recommendations ordered by level of scientific evidence.

| Level of evidence and type of study | Scientific journal | Article summary | Therapy and dose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tursi et al., 201810 | II | J Gastrointestin Liver Dis | Reduction of all symptoms, including abdominal pain. | DIVER® 100 2 capsules/day for 10 days/month for 12 months |

| Systematic review of controlled clinical trials | Q2 | No adverse effects or intolerances, in contrast to mesalazine | ||

| h-Index 42 | ||||

| Carabotti et al., 201725 | II | Nutrients | Patients who eat a high-fibre diet are at lower risk of DDC-related hospitalisation or death | |

| Systematic review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index 75 | ||||

| Dahl et al., 201829 | III | Nutrients | Insufficient evidence. Supports use of fibre in SUDDC | |

| Review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index 75 | ||||

| Mosadeghi et al., 201528 | III | Insufficient evidence. Supports use of fibre in SUDDC | ||

| Review | ||||

| Scaioli et al., 2016 11 | III | Dig Dis Sci | No evidence on eating a high-fibre diet in the treatment of SUDDC | |

| Review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index | ||||

| 113 | ||||

The rationale for using non-absorbable antibiotics like rifaximin to treat DDC is that stasis of the luminal contents of the colon can lead to bacterial overgrowth, which can in turn cause chronic low-grade inflammation of the mucosa.30 A meta-analysis of four randomised clinical trials determined the efficacy of rifaximin (400 mg twice daily, one week every month, for one year, together with fibre supplements) in preventing AD in patients with DD of the colon. This meta-analysis found that 64% of patients treated with rifaximin and standard fibre supplements exhibited no symptoms at one year of follow-up, compared to 34.9% of patients treated with fibre alone.31 Another systematic review of the results of four controlled clinical trials also found rifaximin (800–1200 mg/day, 7 days per month for 12 months) plus fibre supplements to be more beneficial than the use of one of these on its own.30 Other literature reviews also support these findings.32 A recent position paper also recommended the use of cyclical rifaximin therapy in secondary prevention, but not for primary prevention or for treating complicated DDC.24

However, the level of evidence pertaining to the superiority of non-absorbable antibiotics over dietary fibre or fibre supplements is poor. Moreover, both the cost and the efficacy of long-term cyclical non-absorbable antibiotic treatment to prevent AD in all patients with symptoms consistent with DD has been questioned.33 A systematic review published by Maconi17 points to the potential utility of rifaximin, mesalazine, fibre and probiotics, and their possible combinations, in treating SUDDC symptoms, but this has not been backed up by controlled clinical trials (Table 6).17

Use of antibiotics to treat SUDDC, publication recommendations ordered by level of scientific evidence.

| Antibiotics | Type of study | Scientific journal | Article summary | Therapy and dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bianchi et al., 201131 | I | Aliment Pharmacol Ther | 64% of patients receiving rifaximin + fibre were symptom-free after one year of treatment. | 400 mg every 12 h for one week per month for one year |

| Meta-analysis | Q1 | Compared to 34% treated with fibre alone | ||

| h-Index 159 | ||||

| Latella et al., 200930 | II | Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol | Rifaximin + fibre supplements is better than fibre alone | 800–1,200 mg/day for 7 days per month for 12 months |

| Systematic review (4 controlled clinical trials) | Q2 | |||

| h-Index 41 | ||||

| Scaioli et al., 201611 | III | Dig Dis Sci | Improves SUDDC symptoms but does not improve diverticulitis | Fibre plus rifaximin improves SUDDC symptoms |

| Review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index | ||||

| 113 | ||||

| Cuomo et al., 201724 | IV | Dig Liver Dis | Cyclical rifaximin + fibre prevents diverticulitis recurrence in patients with DD | |

| Expert consensus | Q2 | |||

| h-Index 84 | ||||

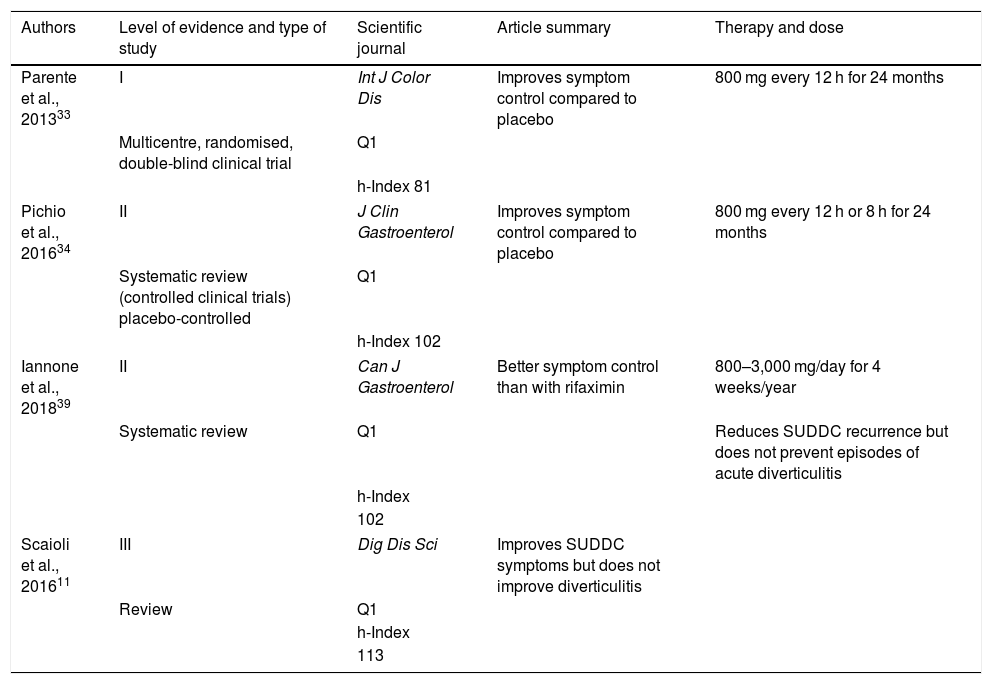

It has been proposed that chronic inflammation in DD is similar to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). That is why medicines containing 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), which are commonly used to treat IBD, have been studied in the management of DD. Parente et al.33 published the results of a multicentre, randomised, double-blind controlled clinical trial, which found that the administration of 800 mg twice a day for 24 months to patients with DD reduced the recurrence of AD episodes and improved symptomatic control compared to patients receiving placebo. The systematic review by Picchio et al.34 reached the same conclusion. It included two placebo-controlled trials of mesalazine 800 mg administered every 12 h and mesalazine 1 g administered every 8 h, respectively, with both finding improved symptom control and fewer recurrences. The reviews conducted by Iannone et al.35 and Scaioli et al.11 found that treatment with mesalazine can reduce SUDDC recurrences, but does not prevent episodes of AD (Table 7).

Use of mesalazine to treat SUDDC, publication recommendations ordered by level of scientific evidence.

| Authors | Level of evidence and type of study | Scientific journal | Article summary | Therapy and dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parente et al., 201333 | I | Int J Color Dis | Improves symptom control compared to placebo | 800 mg every 12 h for 24 months |

| Multicentre, randomised, double-blind clinical trial | Q1 | |||

| h-Index 81 | ||||

| Pichio et al., 201634 | II | J Clin Gastroenterol | Improves symptom control compared to placebo | 800 mg every 12 h or 8 h for 24 months |

| Systematic review (controlled clinical trials) placebo-controlled | Q1 | |||

| h-Index 102 | ||||

| Iannone et al., 201839 | II | Can J Gastroenterol | Better symptom control than with rifaximin | 800–3,000 mg/day for 4 weeks/year |

| Systematic review | Q1 | Reduces SUDDC recurrence but does not prevent episodes of acute diverticulitis | ||

| h-Index | ||||

| 102 | ||||

| Scaioli et al., 201611 | III | Dig Dis Sci | Improves SUDDC symptoms but does not improve diverticulitis | |

| Review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index | ||||

| 113 | ||||

Some studies suggest that certain patients could benefit from the administration of rifaximin or mesalazine in combination with fibre.28 However, optimal treatment duration and the number of doses has not yet been determined, and evidence is limited to two years of follow-up (Table 7).24

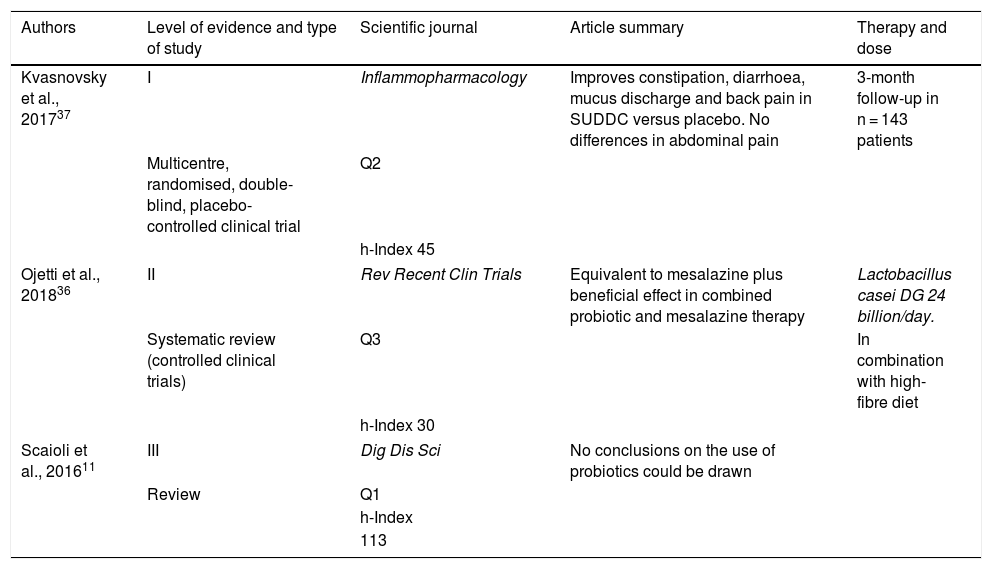

ProbioticsThe main reasons for using probiotics in SUDDC are their potential anti-inflammatory effects and their capacity to improve local immune response. Some reviews suggest that treatment with probiotics is safe and potentially effective in managing patients with SUDDC.30 Three studies have investigated the efficacy of Lactobacillus casei (L. casei DG 24 billion/day) in combination with mesalazine in reducing abdominal symptoms in patients with DD. They found that the use of probiotics was at least equivalent to the use of the anti-inflammatory, and that their administration in combination yielded an even greater beneficial effect.36 A group led by Kvasnovsky et al.37 recently published a placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the daily administration of probiotics. It found that the use of probiotics improved constipation, diarrhoea, mucus discharge and back pain, but no significant differences in terms of abdominal pain were identified compared to placebo (p = 0.11). A recent review concluded that the deficient design and small sample size of most published studies prevent a definitive conclusion on the therapeutic use of probiotics from being reached. In light of the above, large-scale, placebo-controlled clinical trials are still required before probiotics can be conclusively recommended for the management of DDC (Table 8).11

Use of probiotics to treat SUDDC, publication recommendations ordered by level of scientific evidence.

| Authors | Level of evidence and type of study | Scientific journal | Article summary | Therapy and dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kvasnovsky et al., 201737 | I | Inflammopharmacology | Improves constipation, diarrhoea, mucus discharge and back pain in SUDDC versus placebo. No differences in abdominal pain | 3-month follow-up in n = 143 patients |

| Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Q2 | |||

| h-Index 45 | ||||

| Ojetti et al., 201836 | II | Rev Recent Clin Trials | Equivalent to mesalazine plus beneficial effect in combined probiotic and mesalazine therapy | Lactobacillus casei DG 24 billion/day. |

| Systematic review (controlled clinical trials) | Q3 | In combination with high-fibre diet | ||

| h-Index 30 | ||||

| Scaioli et al., 201611 | III | Dig Dis Sci | No conclusions on the use of probiotics could be drawn | |

| Review | Q1 | |||

| h-Index | ||||

| 113 | ||||

In recent years, nutraceutical supplements have come to be accepted as a safer alternative/supplement to conventional therapy. A prospective study demonstrated their efficacy in reducing all symptoms, including abdominal pain, the most common and characteristic symptom of the disease. The drug used in this study was DIVER® (combination of natural ingredients with anti-inflammatory properties: pinaverium bromide, inulin, niacin, cranberry, vitamins B1, B2, B6 and B12, zinc and folic acid). Its international equivalent marketed in Spain is ELDICET®, with a dosage regimen of 2 capsules/day for 10 days/month for 12 months. The authors proposed that these results were due to the specific anti-inflammatory role of this formulation. Furthermore, as no adverse events were reported, they also recommend their use in patients with comorbidities or intolerance to other treatments, such as mesalazine.10 This anti-inflammatory effect could be due to its ingredients. For example, folic acid can help to enhance the activity of regulatory T cells, while vitamin B6 can reduce inflammation both by increasing the activity of interleukin 10 as well as by promoting the growth of Lactobacilli strains, a species of bacteria that appears to be effective in controlling SUDDC symptoms.10

Elective surgeryIt has historically been postulated that, with each additional episode of diverticulitis, the probability of recurrent episodes and the risk of complications increases, while the likelihood of responding to medical treatment decreases. Elective sigmoidectomy should not be based on the number of AD episodes. Experts recommend that the analysis be based on the personalised study of each case, taking into account the time elapsed between the last episode of diverticulitis and surgery, and prioritising minimally-invasive approaches.26 Each clinical situation should be carefully evaluated (persistence of symptoms and signs of complication, age, degree of diverticulitis, immunosuppressed patients, etc.). The severity of any DD-related symptoms or complications must be weighed up against the surgical risk (age, body mass index, comorbidities and specific surgical complications) as well as the risk of severe complications. Age should not be considered an indication for a more aggressive surgical approach. In terms of patients’ quality of life, Justin et al.38 conducted a 200-patient satisfaction survey from 2008 to 2013. The quality of life index score was slightly higher (1.2%; p = 0.77) in the group treated surgically for DD recurrence. In total, 92% of surgically-managed patients were satisfied or completely satisfied with the outcome after the operation. However, the difference in quality of life was only slightly higher (and not statistically significant) for the surgical group. Nevertheless, these results, together with the high rate of patient satisfaction, could support a surgical indication in patients with recurrent episodes of diverticulosis. The duration, but not the severity, of diverticulitis may be associated with an increased risk of recurrence, but this is not an independent risk factor.26 In conclusion, there is insufficient evidence to consider a single risk factor as an independent indication for elective surgery in DD patients.26

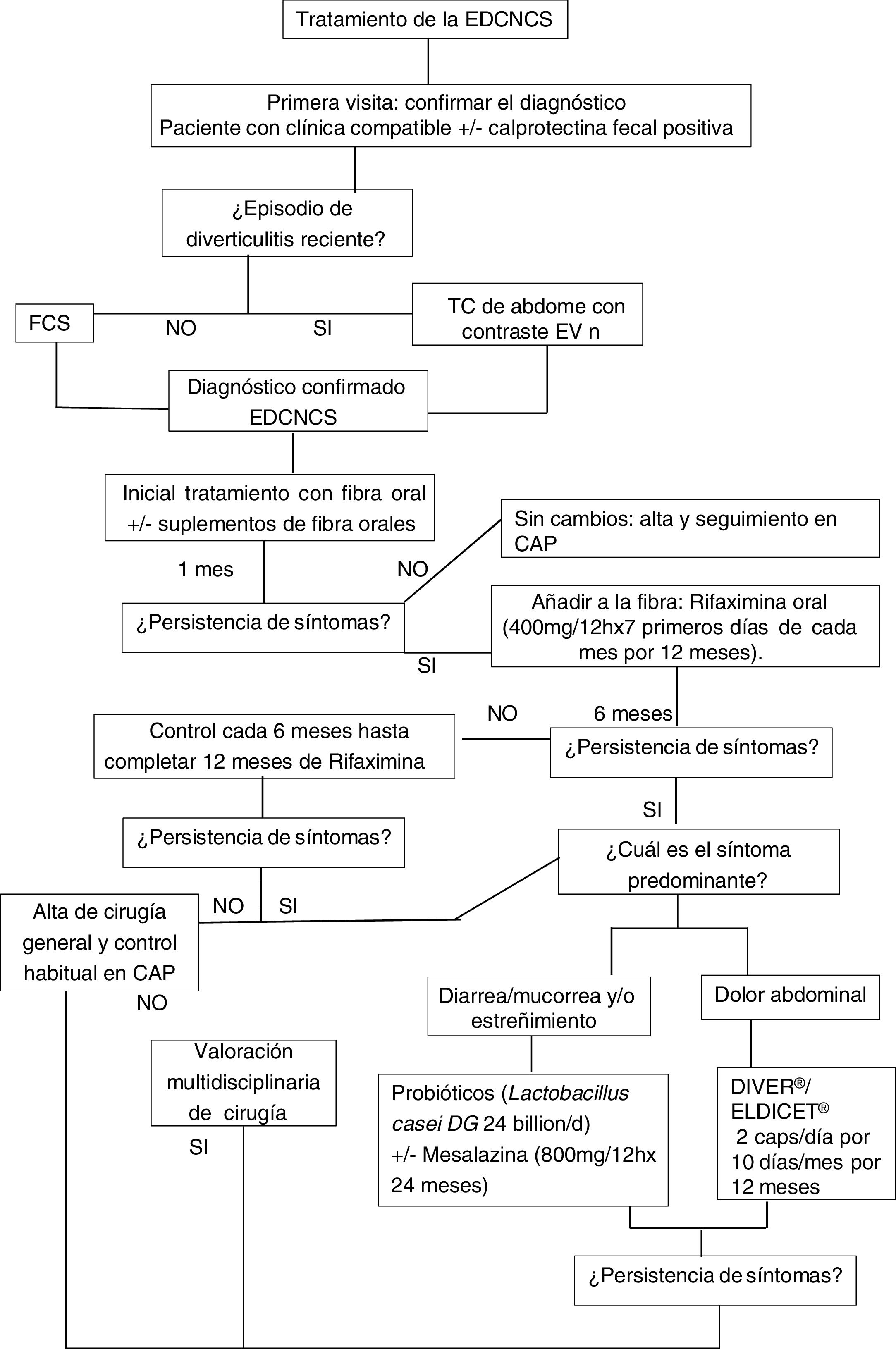

Follow-upIn terms of patient follow-up, no consensus has been reached on how these patients should be managed. However, based on the results of our study, we propose a treatment algorithm that can be summarised as follows (Fig. 2):

- •

During the first visit with a SUDDC patient, a CS or CTC (if available) should be requested/performed to confirm the diagnosis (see “Diagnosis” section). The differential diagnosis with other diseases should be complemented by CRP and faecal calprotectin. It is also important to prescribe a high-fibre diet or daily oral fibre supplements.

- •

Outpatient follow-up to determine the need to add a new treatment, such as rifaximin, as per the patient’s clinical course, prescribing cyclical therapy for the first seven days of each month for 12 months. A six-monthly visit should be scheduled throughout this period to monitor the treatment. Treatment should be combined with fibre throughout this period.

- •

In cases where symptoms are not well controlled, particularly abdominal pain, nutraceuticals should be included as an alternative to conventional treatment.

- •

In patients with predominantly diarrhoea- and/or constipation-like symptoms, consider probiotics ± mesalazine.

- •

At each visit, remember the warning signs for referral to the emergency room to prevent complications.

- •

In terms of elective surgery for patients with SUDDC, no consensus has yet been reached. The decision should be assessed by the treating physicians taking into account the risk of complications and/or the impact on quality of life in each case. We recommend a multidisciplinary approach (general surgeon and gastroenterologists).

SUDDC treatment is based on a multidisciplinary approach and long-term patient follow up (years), taking into account the different available strategies: fibre, rifaximin, mesalazine and nutraceuticals. Surgery should be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Recommendations for SUDDC management may change with the publication of new evidence of higher scientific quality, which is much needed to improve clinical practice. New prospective and randomised studies are required to standardise combined treatment regimens.

AuthorsAll the authors participated in the writing this article and agree to its submission.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Dr David Saavedra-Perez and Dr Yuhamy Curbelo-Peña contributed equally in carrying out this systematic review.

Please cite this article as: Saavedra-Perez D, Curbelo-Peña Y, Sampson-Davila J, Albertos S, Serrano A, Ibañez L, et al. Enfermedad diverticular de colon no complicada sintomática: revisión sistemática del diagnóstico y tratamiento. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:497–518.