The schwannoma is a rare neoplasm with an incidence of 0.6 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.1 It has a plethora of synonyms (neurinoma, neurilemmoma, perineural fibroblastoma, peripheral nerve glioma, etc.). This has made it difficult to record in the medical literature. It was first reported by Verocay in 1910.2 Masson named this type of tumour a “schwannoma” in 1932,3 and Stout coined the term “neurilemmoma” to refer to the same lesion in 1935.4

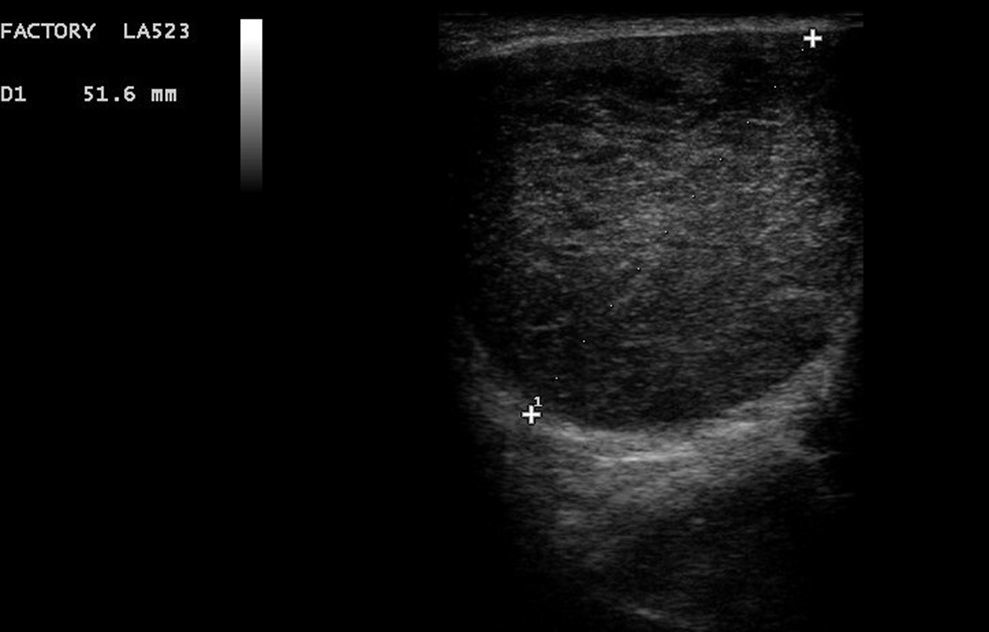

We present the case of a 36-year-old patient who visited the emergency department due to a painful right gluteal tumour, which, according to him, had developed a week earlier. He had no clear signs of infection and his laboratory tests were unremarkable. An ultrasound was performed in the consultation and revealed a gluteal tumour with heterogeneous contents, of approximately 5cm (Fig. 1). A perianal collection of material (probable abscess) was suspected on ultrasound. Consequently, despite the inconsistency between the patient's signs and symptoms and the ultrasound image, it was decided to perform an emergency anal examination under anaesthesia.

The mass was punctured in the operating theatre in several areas, without obtaining purulent contents. Anoscopy revealed no bulges in the anal canal. Subsequently, the perianal and gluteal skin was opened using a longitudinal incision over the mass. This revealed a gelatinous ovoid tumour, which was not consistent with the initial suspicion of a perianal abscess. It was approximately 10×5cm in size, with an elastic consistency and a smooth, bright surface (Fig. 2). The tumour was easily dissected and could be removed en bloc without problems as it was far from the sphincter plane. The patient was discharged after 48h, given that his clinical course was good. There were no recurrences.

The pathology of the specimen was a benign peripheral nerve tumour (schwannoma, neurilemmoma) with a positive S100 marker. All other markers used—c-kit, CD34, EMA, actin and desmin—were negative. The S100 family of proteins is essentially used as a set of tumour markers, since a marked deregulation of S100 proteins has been seen in various tumours such as breast cancer, melanomas and nervous system tumours. These proteins are associated with tumour progression.4,5

Schwannomas represent a type of benign neoplasm of the nerve sheath that originate from Schwann cells and lack axonal fibres. In most cases, they develop at the expense of cranial nerves (especially the vestibular nerve) or posterior roots of spinal nerves. They affect both sexes equally, and usually occur in adulthood (30–50 years of age). They are encapsulated tumours that cause symptoms of compression when they expand inside and outside of the spine. They are not invasive and rarely become malignant. Schwannomas are rarely located in the skin or organs. Solitary skin schwannomas tend to appear in the hypodermis, along the path of a peripheral nerve. They are slow-growing tumours with few symptoms, although they may cause pain and paraesthesia when compressed.6 They are generally located in the laterocervical region or the flexures of the limbs. They have a higher incidence in the upper limbs compared to the lower limbs, in a 2:1 ratio.7 Some syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1, are characterised by the onset of multiple skin schwannomas. This phenomenon is known as “schwannomatosis” or “neurilemomatosis”.

Schwannoma is a tumour encapsulated in a perineural sheath that should be distinguished from other neoplasms of the nerve sheath, especially neurofibroma, which is not encapsulated and has a mucoid component. Its diagnosis is suspected based on its typical appearance on magnetic resonance imaging and confirmed by a histology and immunohistochemistry study. FNAB of these lesions does not usually provide diagnostic certainty due to the cellular pleomorphism particular to these tumours, which may sometimes confuse the pathologist.8

The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal with preservation of the nerve fascicles. It is indicated when they cause discomfort or aesthetic problems.6 These tumours have a good prognosis, since they rarely become malignant (less than 0.001% in isolated schwannomas). In most cases, the malignant component exhibits an epithelioid morphology.9 In neurofibromatosis type 1, the rate at which the lesion becomes malignant increases to 18%.10

Please cite this article as: González Plo D, García Pavía A, León Gámez CL, Pueyo Rabanal A, Sánchez Turrión V. Tumoración perianal que simulaba ser un absceso. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:398–399.