The presence of portal venous gas (PVG) is a rare radiological finding secondary to a gastrointestinal problem. Management of PVG in the emergency department is challenging. The most common cause is intestinal ischaemia, which is associated with a high mortality rate.1 However, PVG can also occur in patients with diseases which have a more favourable prognosis, such as acute gastric dilatation (AGD).1,2 In these cases, it is difficult to choose the best therapeutic approach, and most clinicians opt for conservative management. We present a case in which conservative management was chosen, and review the literature on non-obstructive AGD with PVG.

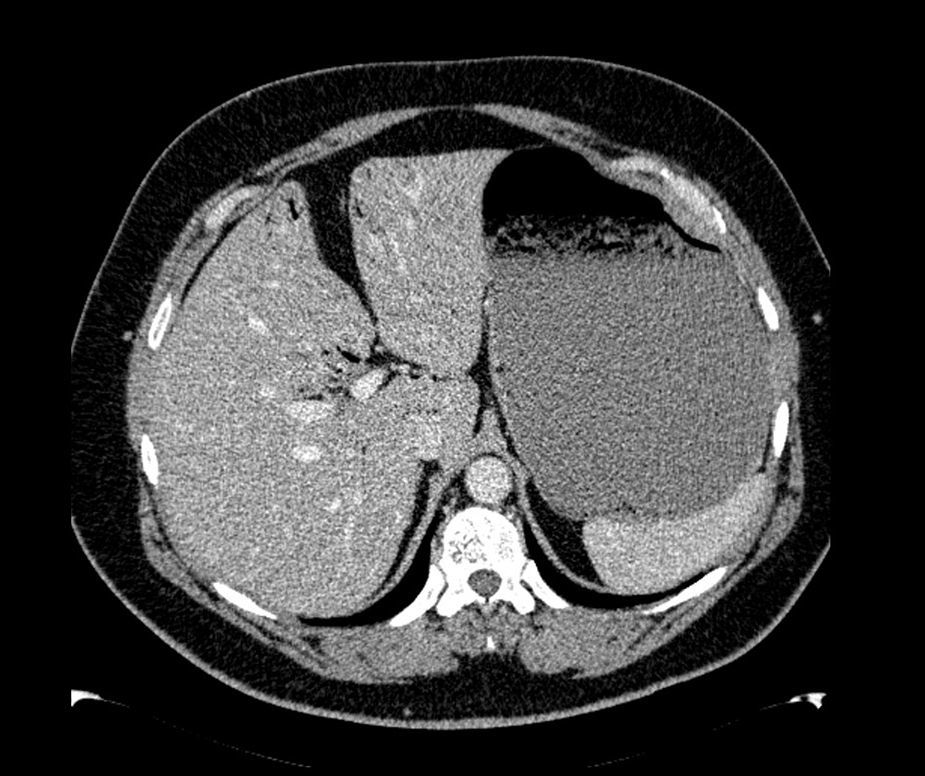

The patient was a 47-year-old man with a history of hypertension and personality disorder, with several previous suicide attempts, the last one occurring one week previously involving massive intake of benzodiazepines and gabapentin. He presented at the emergency department due to abdominal pain and diarrhoea lasting 4 days, with no fever or other associated symptoms. The physical examination showed good overall status, with a soft and depressible abdomen, pain in the suprapubic region and both iliac fossae, with no signs of peritoneal irritation. The only finding of note on laboratory tests was 11,300leukocytes/mm3, and slightly elevated C-reactive protein. Stool tests and Clostridium difficile culture were negative. Plain abdominal X-ray showed significant gastric dilatation. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed massive gastric dilatation with intrahepatic portal venous gas, with no evidence of gastric pneumatosis, pneumoperitoneum, free fluid, or intra-abdominal disease (Fig. 1). The patient improved both clinically and analytically after placement of a nasogastric tube. The study was completed with a gastroscopy, which showed gastropathy due to irritation. The biopsy showed mild chronic gastritis. The patient was discharged after 10 days with good overall status, asymptomatic, and with no evidence of portal gas in the follow-up CT scan.

PVG was reported for the first time in neonates with enterocolitis in 1955, followed by the first case in adults in 1960.1 Since then, the number of cases reported has increased steadily. The presence of PVG is secondary to different gastrointestinal disorders. The most frequent cause in adults is intestinal ischaemia (43–72%), intra-abdominal abscesses (6–11%), inflammatory bowel disease (8%) or digestive tract dilatation (3–12%).1 The main pathogenic factors associated with PVG are: intestinal mucosa defects, elevated gastrointestinal intraluminal pressure, and the presence of gas-forming bacteria.1–4

Although portal gas can sometimes be detected on a plain abdominal X-ray, the diagnostic technique of choice is CT, which can also evaluate the underlying cause. Radiologically, PVG differs from pneumobilia by the presence of gas in peripheral radicles extending to within 2cm of the liver capsule.3 The presence of PVG has hitherto been considered an ominous sign, although prognosis now depends on the severity of the associated underlying process. A review of 182 patients with PVG found that 46% underwent surgery, with an overall mortality rate of 39%:75% in patients with intestinal ischaemia, and 30% in PVG due to digestive tract dilatation, abscesses and gastric ulcer.1 Other gastric causes of PVG are emphysematous gastritis and acute dilatation. AGD is usually secondary to a gastric obstruction (pyloric stenosis, gastric cancer, volvulus, incarcerated hernia, superior mesenteric artery syndrome). Non-obstructive AGD, however, is very rare, and is usually related to eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia, psychogenic polyphagia). It has also been described in patients with cerebral palsy, diabetic gastropathy, autonomic neuropathy, alcoholism, multiple trauma, ingestion of caustic substances, tricyclic antidepressants and benzodiazepines, cannabis abuse and postoperative complications of antireflux surgery. It is also associated with oral intake after long periods of postoperative fasting and famine victims. The presence of PVG in patients with AGD is also exceptional, and is usually located exclusively in the portal vein and its intrahepatic branches, not in the region of the mesenteric axis, unlike other intestinal causes of PVG.5

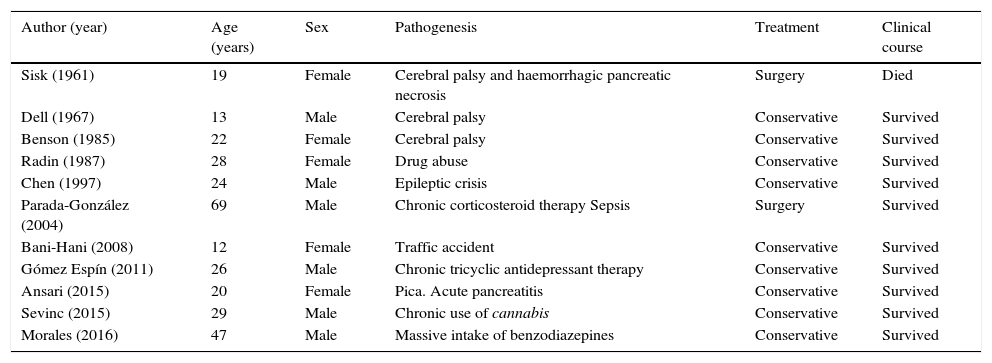

We conducted a review of the literature and obtained a further 10 published cases of PVG exclusively related to non-obstructive AGD (Table 1).2–10 The mean age of patients is 28 years (12–69 years), and there are no significant gender differences (6 men and 5 women). The only common pathogenic factor was elevated intra-abdominal pressure. Treatment was usually conservative (nasogastric tube, nil by mouth and fluid therapy). No cases of gastric perforation were reported, and only 2 patients underwent surgery (18.1%): the first in 1961, when few diagnostic techniques were available. This patient died due to associated haemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis.10 The second case underwent surgery due to diagnostic uncertainty; no intraoperative macroscopic abnormalities were observed.4 For this reason, we believe that exploratory laparotomy should be reserved for cases in which there is a suspicion of associated surgical abdominal disease (severe pancreatitis, ischaemia or intestinal obstruction), signs of peritoneal irritation, or a deteriorating clinical course. The mortality rate was 9%,10 far lower than that reported in historical reviews of PVG cases.

Published cases of PVG due to non-obstructive AGD.

| Author (year) | Age (years) | Sex | Pathogenesis | Treatment | Clinical course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sisk (1961) | 19 | Female | Cerebral palsy and haemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis | Surgery | Died |

| Dell (1967) | 13 | Male | Cerebral palsy | Conservative | Survived |

| Benson (1985) | 22 | Female | Cerebral palsy | Conservative | Survived |

| Radin (1987) | 28 | Female | Drug abuse | Conservative | Survived |

| Chen (1997) | 24 | Male | Epileptic crisis | Conservative | Survived |

| Parada-González (2004) | 69 | Male | Chronic corticosteroid therapy Sepsis | Surgery | Survived |

| Bani-Hani (2008) | 12 | Female | Traffic accident | Conservative | Survived |

| Gómez Espín (2011) | 26 | Male | Chronic tricyclic antidepressant therapy | Conservative | Survived |

| Ansari (2015) | 20 | Female | Pica. Acute pancreatitis | Conservative | Survived |

| Sevinc (2015) | 29 | Male | Chronic use of cannabis | Conservative | Survived |

| Morales (2016) | 47 | Male | Massive intake of benzodiazepines | Conservative | Survived |

In conclusion, the presence of PVG secondary to non-obstructive AGD is a very rare radiological finding caused by an unknown pathogenic mechanism. CT scan, which can also rule out other causes of PVG, is the diagnostic technique of choice. Conservative treatment is usually effective and avoids unnecessary surgery. Unlike other causes of PVG, the prognosis is usually very favourable, provided there is no other associated severe abdominal disease.

Please cite this article as: Morales Artero S, Castellón Pavón CJ, Cereceda Barbero P, Pérez Algar C, Larraz Mora E. Gas portal secundario a dilatación gástrica aguda no obstructiva. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:673–675.