Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) has been defined as the presence of gas/air in the portal venous system. It has been traditionally associated with ischemic bowel processes, and has been considered as an ominous finding with a mortality rate up to 75%.1

HPVG has been described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mostly in Crohn's Disease (CD).2,3 We present a case of HPVG and a literature review of the reported cases of HPVG in ulcerative colitis (UC).

A 45-year-old-woman was diagnosed with left-sided UC 15 years ago. She started treatment with azathioprine after a steroid-dependent flare-up in 2010, adding infliximab in 2012 due to the persistence of UC activity.

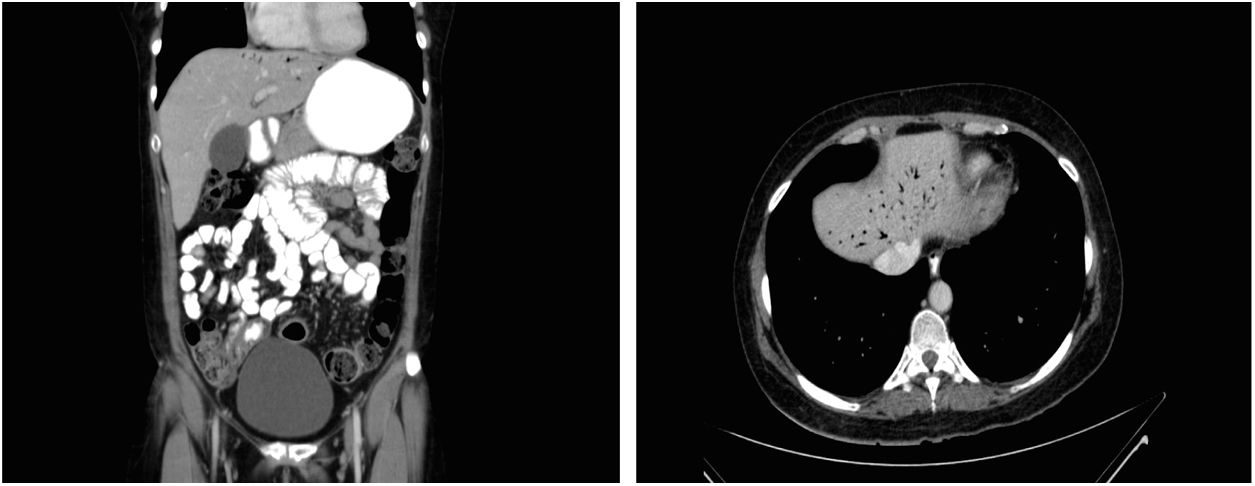

In October 2014, the patient was admitted in our emergency care unit presenting acute severe abdominal pain referred to epigastrium, nausea, tachycardia and fever (39.3°C). She did not report evidence of clinical UC activity in recent months. In serial blood samples an increase in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP], up to 63mg/L from normal values within the first 24h) was observed. Simple chest and abdominal X-rays showed no relevant findings. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed, and HPVG was observed in the left lobe of the liver (Fig. 1). Other intra-abdominal complications were ruled out and inflammatory changes in the rectum and sigma were observed, suggesting active UC. Immediately afterwards, a rectosigmoidoscopy was performed in which continuous mucosal damage with moderate inflammation up to 40cm from the anal verge was identified.

The patient was admitted in our department for conservative management. Endovenous antibiotics (metronidazole plus ceftriaxone) and steroids (metyl-prednisolone 1mg/kg daily) were initiated. Both azathioprine and infliximab treatment were discontinued.

The patient promptly reported feeling better and remained afebrile. Subsequent blood samples showed a progressive decrease of CRP (6.8mg/L at discharge). Urine and blood cultures, as well as stool samples studies, were negative. At the 7th day of admission, a control CT-scan was performed, with complete HPVG resolution. Thereafter, endovenous steroids were changed for oral steroids. The patient remained in our unit for a total of 10 days and at the time she was discharged, antibiotics were stopped.

Liebman1 reported 64 HPVG patients in which up to 72% cases were associated with bowel necrosis, with a global mortality rate of 75%, advocating for an aggressive management and urgent surgical exploration once this condition was diagnosed. More recently, an updated review of 182 patients with HPVG reported an overall mortality rate of 39%.2 Other apparently more benign conditions, such as gastric ulcer, complications of endoscopic procedures and IBD, were associated with HPVG.2 Some of these conditions reacted favorably to conservative management, suggesting that HPVG itself is not a predictor of poor outcome.1,2,4,5

Abdominal ultrasound and CT-scan are the radiological modalities used nowadays to diagnose HPVG.3,5 The classical appearance of this entity is that of branching lucencies within 2cm of the liver capsule, predominantly in the left lobe, which differs from biliary gas because the latter is associated with air within the central portion of the liver1–5 (Fig. 1).

The pathogenesis of HPVG could be explained as follows: (1) the passage of intraluminal air or gas-forming bacteria into the portomesenteric venous system due to mucosal disruption (2) increased bowel pressure that leads to bowel distension with mucosal disruption, described mainly in iatrogenic procedures such as colonoscopies and barium enemas; (3) the existence of abdominal infections.1,5

It seems that mucosal damage, as well as bowel distension secondary to increased bowel pressure in the setting of diagnostic studies, are the main factors that lead to the occurrence of HPVG in IBD patients.1,2,4,5

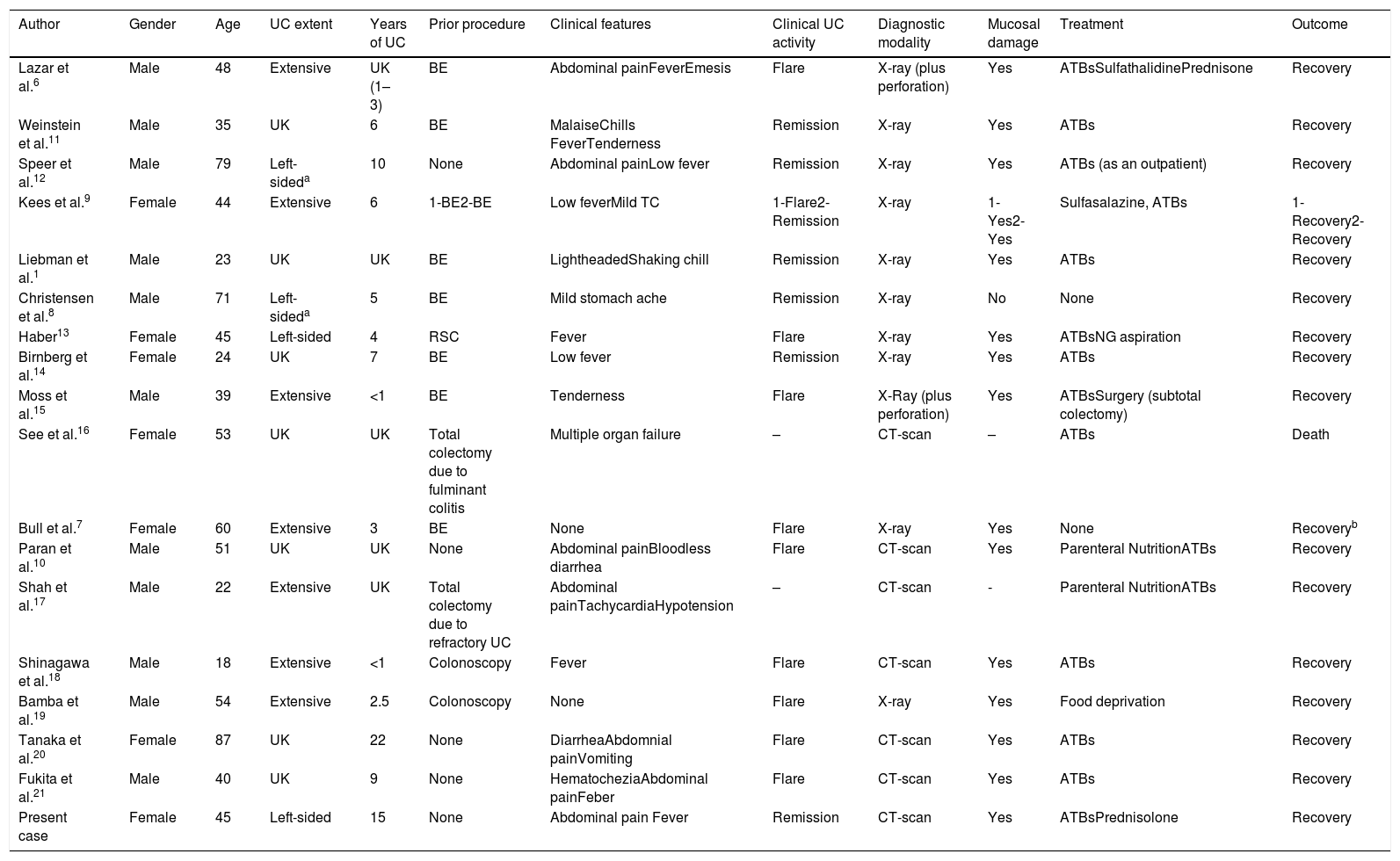

With the present case, only 18 cases of HPVG in patients with UC have been described in the English literature to date (Table 1).1,6,7–21 Sixty one percent of cases were found after a barium enema or a colonoscopy. The majority of cases (88%) were managed conservatively. The mortality rate was 5% (one out of 18 patients), although it seems that in this case the fatal outcome was due to a complications occurred after an emergency surgery in the setting of fulminant colitis.16

Cases of hepatic portal venous gas in ulcerative colitis.

| Author | Gender | Age | UC extent | Years of UC | Prior procedure | Clinical features | Clinical UC activity | Diagnostic modality | Mucosal damage | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lazar et al.6 | Male | 48 | Extensive | UK (1–3) | BE | Abdominal painFeverEmesis | Flare | X-ray (plus perforation) | Yes | ATBsSulfathalidinePrednisone | Recovery |

| Weinstein et al.11 | Male | 35 | UK | 6 | BE | MalaiseChills FeverTenderness | Remission | X-ray | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Speer et al.12 | Male | 79 | Left-sideda | 10 | None | Abdominal painLow fever | Remission | X-ray | Yes | ATBs (as an outpatient) | Recovery |

| Kees et al.9 | Female | 44 | Extensive | 6 | 1-BE2-BE | Low feverMild TC | 1-Flare2-Remission | X-ray | 1-Yes2-Yes | Sulfasalazine, ATBs | 1-Recovery2-Recovery |

| Liebman et al.1 | Male | 23 | UK | UK | BE | LightheadedShaking chill | Remission | X-ray | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Christensen et al.8 | Male | 71 | Left-sideda | 5 | BE | Mild stomach ache | Remission | X-ray | No | None | Recovery |

| Haber13 | Female | 45 | Left-sided | 4 | RSC | Fever | Flare | X-ray | Yes | ATBsNG aspiration | Recovery |

| Birnberg et al.14 | Female | 24 | UK | 7 | BE | Low fever | Remission | X-ray | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Moss et al.15 | Male | 39 | Extensive | <1 | BE | Tenderness | Flare | X-Ray (plus perforation) | Yes | ATBsSurgery (subtotal colectomy) | Recovery |

| See et al.16 | Female | 53 | UK | UK | Total colectomy due to fulminant colitis | Multiple organ failure | – | CT-scan | – | ATBs | Death |

| Bull et al.7 | Female | 60 | Extensive | 3 | BE | None | Flare | X-ray | Yes | None | Recoveryb |

| Paran et al.10 | Male | 51 | UK | UK | None | Abdominal painBloodless diarrhea | Flare | CT-scan | Yes | Parenteral NutritionATBs | Recovery |

| Shah et al.17 | Male | 22 | Extensive | UK | Total colectomy due to refractory UC | Abdominal painTachycardiaHypotension | – | CT-scan | - | Parenteral NutritionATBs | Recovery |

| Shinagawa et al.18 | Male | 18 | Extensive | <1 | Colonoscopy | Fever | Flare | CT-scan | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Bamba et al.19 | Male | 54 | Extensive | 2.5 | Colonoscopy | None | Flare | X-ray | Yes | Food deprivation | Recovery |

| Tanaka et al.20 | Female | 87 | UK | 22 | None | DiarrheaAbdomnial painVomiting | Flare | CT-scan | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Fukita et al.21 | Male | 40 | UK | 9 | None | HematocheziaAbdominal painFeber | Flare | CT-scan | Yes | ATBs | Recovery |

| Present case | Female | 45 | Left-sided | 15 | None | Abdominal pain Fever | Remission | CT-scan | Yes | ATBsPrednisolone | Recovery |

ATBs, Antibiotics; BE, Barium Enema; CT-scan, Computer Tomography-scan; NG, Naso-gastric; RSC, Rectoscopy; TC, Tachycardia; UC, Ulcerative Colitis; UK, Unknown, X-ray: plain film abdominal radiography.

Therefore, it seems that the management and treatment of HPVG has to be addressed to the underlying disease, which will determine the prognosis of the patients.

Author contributionsMurzi M, Oblitas E, Garcia-Planella E and Gordillo J designed the case report; Posso M provided advice on performing the systematic review and searched in the databases; Murzi M and Gordillo J screened the articles and selected the full texts; Murzi M wrote the paper; Soriano G, Gordillo J, Pernas JC and Garcia-Planella E provided clinical advice; Soriano G, Gordillo J and Garcia-Planella E revised the paper. All authors contributed and approved the last version of the manuscript.

FundingNo funding was provided for this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thanks German Soriano and David Bridgewater for the help with the translation of the present manuscript.