Acute oesophageal necrosis is an uncommon condition characterised by images of diffuse black pigmentation of the oesophagus on endoscopy. It is caused by ischaemia and usually manifests as upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGB). The mortality rate is high and management varies from intensive medical treatment to surgery when associated with perforation.

We present a case of black oesophagus associated with mediastinitis after combined liver-kidney transplantation (CLKT).

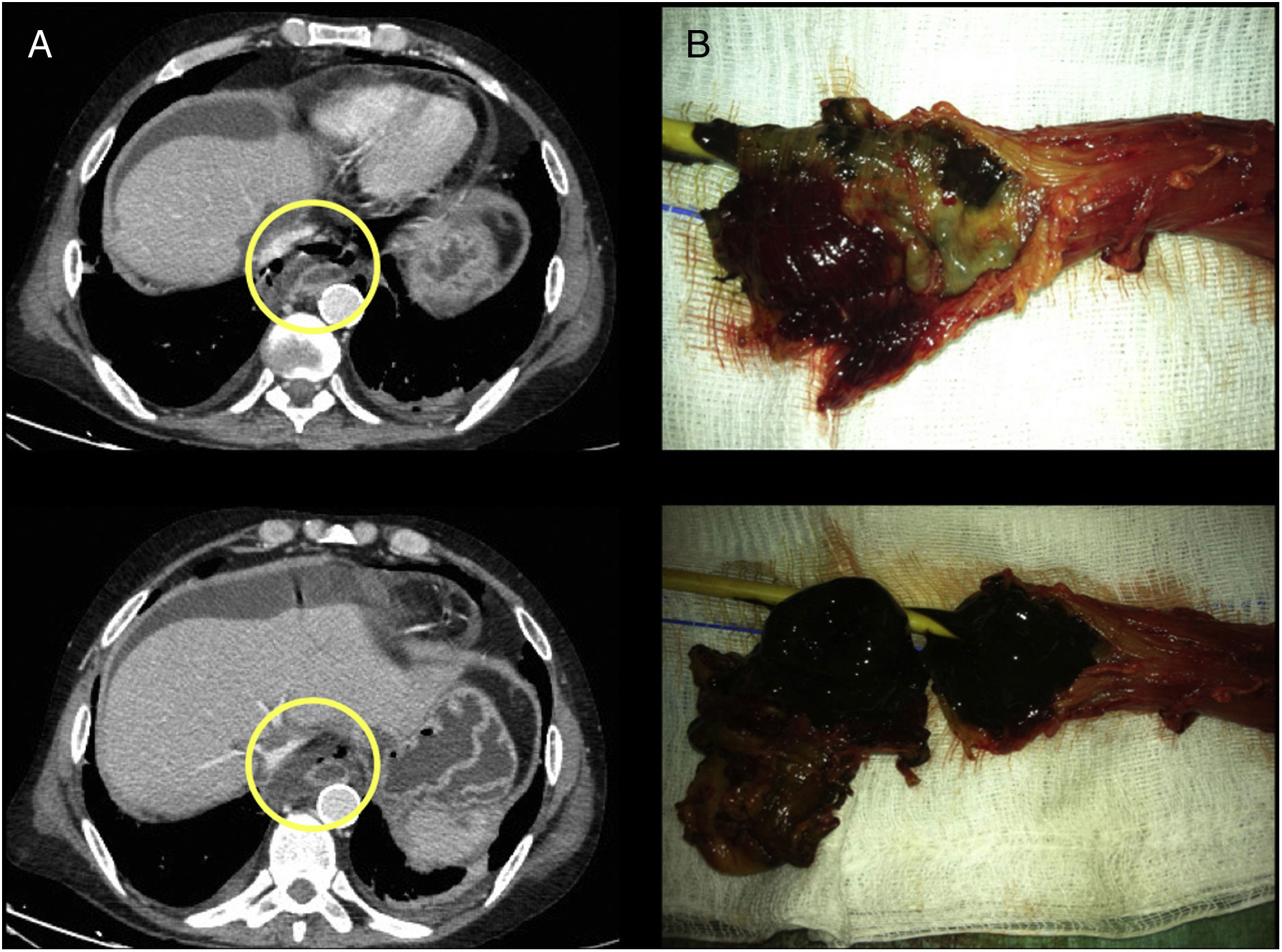

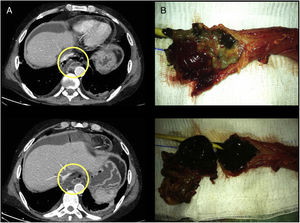

This was a 50-year old male diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis of liver, Child-Pugh A5, MELD 20, portal hypertension and chronic kidney failure on peritoneal dialysis. CLKT was indicated. During the procedure, the patient required multiple transfusions and suffered a cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity for 2min. In the immediate postoperative period, he was haemodynamically stable and the investigations performed (analyses, serial Doppler and cholangiogram) were normal. On postoperative day thirteen, the patient became haemodynamically unstable and had UGB. Gastroscopy showed black oesophagus due to circumferential necrosis along the entire length. CT scan showed pneumomediastinum and a mediastinal collection (Fig. 1A), with urgent surgical intervention indicated. The oesophagus was found to have transmural necrosis with a perforation in the lower segment causing mediastinitis. Transhiatal oesophagectomy, debridement and mediastinal lavage, cervical oesophagostomy and Witzel gastrostomy were performed. The pathology report revealed complete necrosis of the oesophageal mucosa secondary to acute necrotising oesophagitis (Fig. 1B). The patient made slow but satisfactory progress. One month after the transplant, he had a post-anastomotic thrombosis of the hepatic artery, but there were no clinical-analytical repercussions and it was managed conservatively. He was discharged home tolerating the gastrostomy tube well 72 days post-transplant. Just over three months after the transplant, the patient developed ischaemic cholangiopathy with the need for internal-external biliary drainage as bridging therapy for a re-transplant. At 14 months, due to the stability of his nutritional status and liver function, transit reconstruction was indicated prior to liver re-transplantation, with the aim of not hindering the mobilisation of the plasty afterwards. Retrosternal gastroplasty was performed with manual end-to-end oesophagogastric anastomosis and placement of a jejunal feeding tube. On day eight, he was found to have necrosis of the gastroplasty with cervical anastomotic dehiscence. He required re-intervention with resection of the plasty and new cervical oesophagostomy. The patient died as a result of multiorgan failure secondary to sepsis.

Black oesophagus is highly unusual, occurs predominantly in males (4:1) and has an estimated prevalence of 0.008–0.2%.1,2 The main risk factors are diabetes, cancer, high blood pressure, chronic lung disease, alcoholism, coronary heart disease, cirrhosis, kidney failure, post-operative, immunosuppression and malnutrition. Triggers include hypoperfusion, gastroesophageal reflux and infections. All this leads to insufficient function of the protective barriers of the mucosa and tissue ischaemia with the resulting macroscopic black oesophagus appearance.1–4 The main complication is oesophageal perforation and mediastinitis, with a mortality rate of around 40%.2

It usually manifests as UGB, with endoscopy findings of diffuse circumferential involvement, with friable and blackened mucosa. It characteristically affects the distal segment of the oesophagus, with abrupt cessation at the gastroesophageal mucosal junction.1,2,5 The differential diagnosis must be established with other disorders which can cause similar endoscopic images (such as melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, pseudomelanosis, pseudomembranous oesophagitis and the ingestion of corrosives).5

This case involved at least seven of the known risk factors: hypoperfusion, cirrhosis, post-operative, kidney failure, hypertension, immunosuppression and malnutrition.4 No concomitant infection was diagnosed. We would suggest that the hypoperfusion which occurred during surgery was the main determinant,3 with multiple transfusions and then cardiac arrest, causing tissue ischaemia, in a patient with little physiological reserve.

Initial treatment consists of aggressive resuscitation, the use of proton pump inhibitors and the correction of trigger factors. In the event of complications, such as perforation or mediastinitis,1–3,5 emergency surgery may be necessary.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of black oesophagus in a CLKT recipient with successful treatment. Despite the perforation and mediastinitis in a patient who was immunocompromised because of the CLKT, the cause of death was the complications deriving from the transit reconstruction 14 months after the combined transplant.

FundingNo funding was received.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Aranda Escaño E, Prieto Calvo M, Perfecto Valero A, Tellaeche de la Iglesia M, Gastaca Mateo M, Valdivieso López A. Esófago negro tras doble trasplante hepatorrenal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:25–27.