Rumination syndrome is a functional disorder characterized by the involuntary regurgitation of recently swallowed food from the stomach into the mouth, from where it can be re-chewed or expelled. Clinically, it is characterized by repeated episodes of effortless food regurgitation. The most usual complaint is frequent vomiting. The physical mechanism that generates regurgitation events is dependent on an involuntary process that alters abdominal and thoracic pressures accompanied by a permissive oesophageal-gastric junction. The diagnosis of rumination syndrome is clinical, highlighting the importance of performing an exhaustive anamnesis on the characteristics of the symptoms. Complementary tests are used to corroborate the diagnosis or rule out organic pathology. Treatment is focused on behavioural therapies as the first line, reserving pharmacological and surgical therapies for refractory cases.

El síndrome de rumiación es un trastorno funcional caracterizado por la regurgitación involuntaria de los alimentos recientemente ingeridos desde el estómago hacia la boca, donde puede ser remasticada o expulsada. Desde el punto de vista clínico, se caracteriza por episodios repetidos de regurgitación de alimentos sin esfuerzo, siendo la queja habitual los vómitos frecuentes. El mecanismo físico que genera los eventos de regurgitación es depende de un proceso involuntario que altera las presiones abdominal y torácica acompañado de una unión esofágo-gástrica permisiva. El diagnóstico del síndrome de rumiación es clínico, destacando la importancia de realizar una anamnesis exhaustiva sobre las características de los síntomas. Las pruebas complementarias se utilizan para corroborar el diagnóstico o descartar otra patología orgánica. El tratamiento está enfocado a terapias conductuales como primera línea, reservando las terapias farmacológicas y quirúrgicas para casos refractarios.

Rumination syndrome is a functional disorder characterised by involuntary regurgitation of recently ingested foods from the stomach to the mouth, where they may be rechewed or spat out. In modern medicine, the first reports of rumination in humans date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.1 Rumination syndrome was initially believed to be a disease exclusively limited to paediatric patients and people with cognitive developmental abnormalities2; however, it is now known that it can be seen in any age group. Although it is considered an uncommon disease, there is little epidemiological information on its incidence and prevalence.3 In recent years, rumination syndrome has been classified as two entities: as a functional disorder, according to the Rome IV criteria,4 and as an eating disorder, according to the DSM-5.5 This classification has the following limitations: the Rome IV criteria do not require mucosal lesion or obstructive organic disease to be ruled out, and the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria require an eating disorder to be ruled out.

From a clinical point of view, rumination syndrome is characterised by repeated episodes of regurgitation without effort of both solid and liquid foods that is neither preceded by nausea nor accompanied by retching3 or acid regurgitation. Indeed, the appearance of the latter rules out episodes of regurgitation. Another significant clinical characteristic is that water intake facilitates episodes of regurgitation. The clinical significance of rumination syndrome ranges from minor social inconveniences to co-occurrence with significant nutritional abnormalities.6

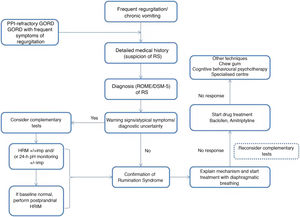

Patients usually complain of frequent vomiting. The vast majority are erroneously diagnosed with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), gastroparesis or functional vomiting. It is important to note that diagnostic delays are common: patients are subjected to multiple unnecessary tests and administered ineffective treatments, entailing a significant increase in expenses, a decrease in quality of life and negative psychological effects.7–9

EpidemiologyThe exact prevalence of rumination syndrome in adults is unknown. Population studies of gastrointestinal diseases have estimated a prevalence of around 1%.10,11 Higher prevalences have been reported in various selected cohorts. A study of adult patients diagnosed with proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-refractory GORD found a prevalence of rumination syndrome of 20%.12 Another risk group consists of patients with psychiatric diseases, in which prevalences close to 8% have been reported in cases with fibromyalgia or eating disorders.13,14 In addition, rumination syndrome is more common in people with other functional disorders such as dyspepsia, dizziness or headaches of unknown aetiology.15 In a study of 438 patients with defecation disorders, 57 had concomitant rumination syndrome. Of them, 93% had a psychiatric comorbidity; figuring prominently among such comorbidities were eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia.16

There appears to be a higher prevalence in the paediatric and adolescent population versus the adult population. Population studies in different countries have reported a prevalence of around 5%.17–19 As in adults, certain risk groups have even higher prevalences. A study of paediatric patients with PPI-refractory GORD detected a prevalence of rumination syndrome of 43%.20 Another study, conducted in paediatric patients suffering from chronic vomiting with inconclusive initial diagnostic tests, found a prevalence of rumination syndrome of 60%.21 It is important to note that, as this entity is generally unknown, the actual prevalence of rumination syndrome is probably underestimated.

PathophysiologyRuminating consists of rechewing food that returns to the mouth from the chamber some animals have for this purpose to digest food by means of chewing, swallowing and regurgitating the ruminant matter, then rechewing it.22 In humans, rumination syndrome is considered an unnatural mode of eating and digesting.23 In some cases, symptom onset may be associated with an identifiable stress-related trigger, such as a viral infection, emotional event or traumatic physical injury. However, in up to one third of cases, it is not possible to identify a trigger of the onset of symptoms.9,15 Although the pathogenesis of rumination syndrome has not been thoroughly elucidated, in the past decade, the physical mechanism that causes regurgitation events has been described and psychological theories as to the possible disease-triggering mechanisms have been put forward.

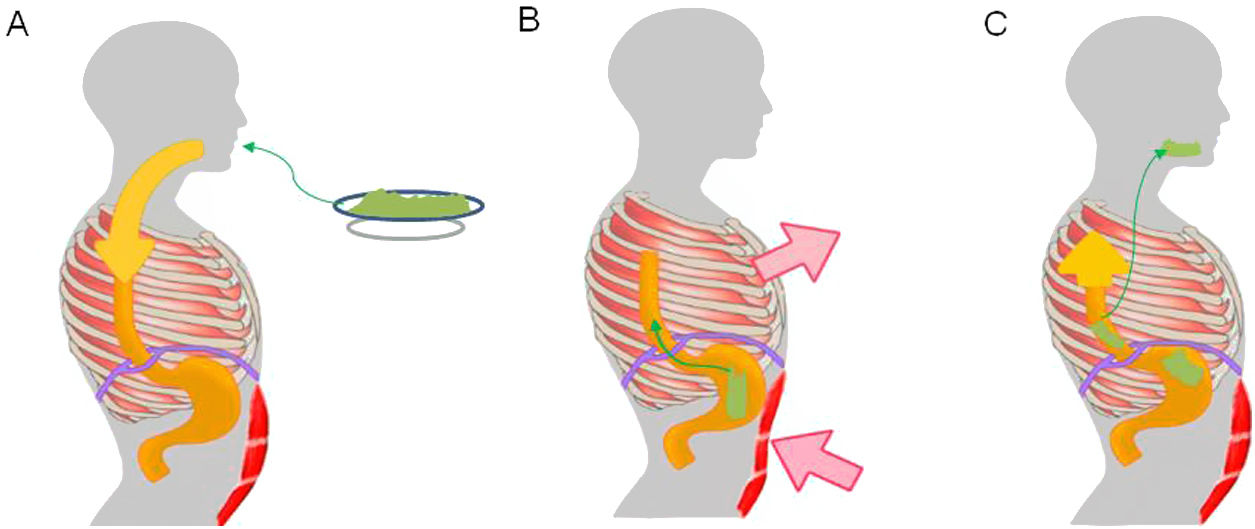

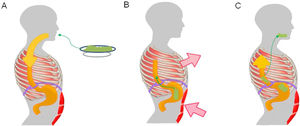

Regurgitation events in rumination syndrome occur when there is a gastro-oesophageal gradient that enables the stomach contents to flow towards the mouth. This gradient is produced when there is an increase in intra-abdominal pressure associated with negative intrathoracic pressure and a permissive gastro-oesophageal junction.24 A study conducted in patients with rumination syndrome using electromyography of the thoracoabdominal musculature found regurgitation events to be associated with contraction of the intercostal musculature (thoracic suction) accompanied by contraction of the anterior abdominal muscles (abdominal compression).24 This mechanism of muscle contraction is generally perceived neither by patients nor by their families.25 To enable the flow of contents from the gastric cavity, the gastro-oesophageal junction relaxes. One study, using fluoroscopy in patients with rumination, found displacement of the gastro-oesophageal junction towards the chest during episodes of regurgitation, causing a "pseudohernia".26 This phenomenon may account for the drops in baseline pressure of the gastro-oesophageal junction detected by oesophageal manometry during episodes of regurgitation.26–28 In addition, studies conducted with high-resolution oesophageal manometry have demonstrated that regurgitation events in rumination are associated with gastric pressurisation in excess of 30 mmHg.29,30 This phenomenon distinguishes regurgitation associated with rumination from regurgitation associated with GORD.

From a psychopathological point of view, rumination in humans acts as a habit or reflex that develops as a result of a stimulus. Affected patients usually report physical sensations prior to the start of rumination similar to the premonitory urges experienced by patients with motor tics.31 The sensation of regurgitation is believed to temporarily resolve the premonitory urge, thus reinforcing the phenomenon of involuntary thoracoabdominal contractions.

Furthermore, secondary behaviour mechanisms that positively reinforce regurgitation events have been reported,32 including: the association of symptoms with different foods in particular, the perception of postprandial abdominal discomfort (hypervigilance) and specific social situations (stress).31

Kessing et al.29 studied patients diagnosed with rumination syndrome and GORD who reported very frequent episodes of regurgitation using high-resolution oesophageal manometry and 24-h ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring. In their study, they reported three mechanisms leading to episodes of rumination. The first mechanism or primary rumination is that which occurs spontaneously, with no identifiable triggering factor. The second mechanism or secondary rumination syndrome is that which occurs almost exclusively after an episode of gastro-oesophageal reflux. A third mechanism was recently reported in which episodes of rumination are preceded by supragastric belching.33 Interestingly, supragastric belching is another gastrointestinal functional disorder of a behavioural nature that often results from feelings of abdominal discomfort.34

Clinical presentation and differential diagnosisThe main clinical symptom is postprandial regurgitation without effort of recently ingested foods towards the oral cavity. Food can be rechewed and reswallowed or spat out, depending in most cases on the social context.35 Rumination may start during food intake or 10−15 min after having finished eating and the events may persist for up to two hours. Rumination may present with fluids alone or with solid foods. Fluid intake characteristically facilitates rumination of solid foods.3 Regurgitation lacks the acidic, bitter taste of the gastric juices, and the flavour is usually described as similar to that of the recently ingested foods. Symptoms tend to remit once the ruminant matter takes on that acidic, bitter taste; due to its voluntary but unconscious origin, it does not occur during sleep.6 Therefore, if night-time regurgitation is present, other diseases such as GORD must be suspected. In some cases, it is accompanied by a feeling of early fullness and abdominal discomfort, as in dyspepsia.25 Increased dental caries and erosions have been reported in the paediatric population; however, in adults, these appear to be less common.36 It is important to note that up to half of patients with rumination syndrome report weight loss, which in some cases is very significant,30 although these patients rarely also have undernutrition or significant electrolyte imbalances.6

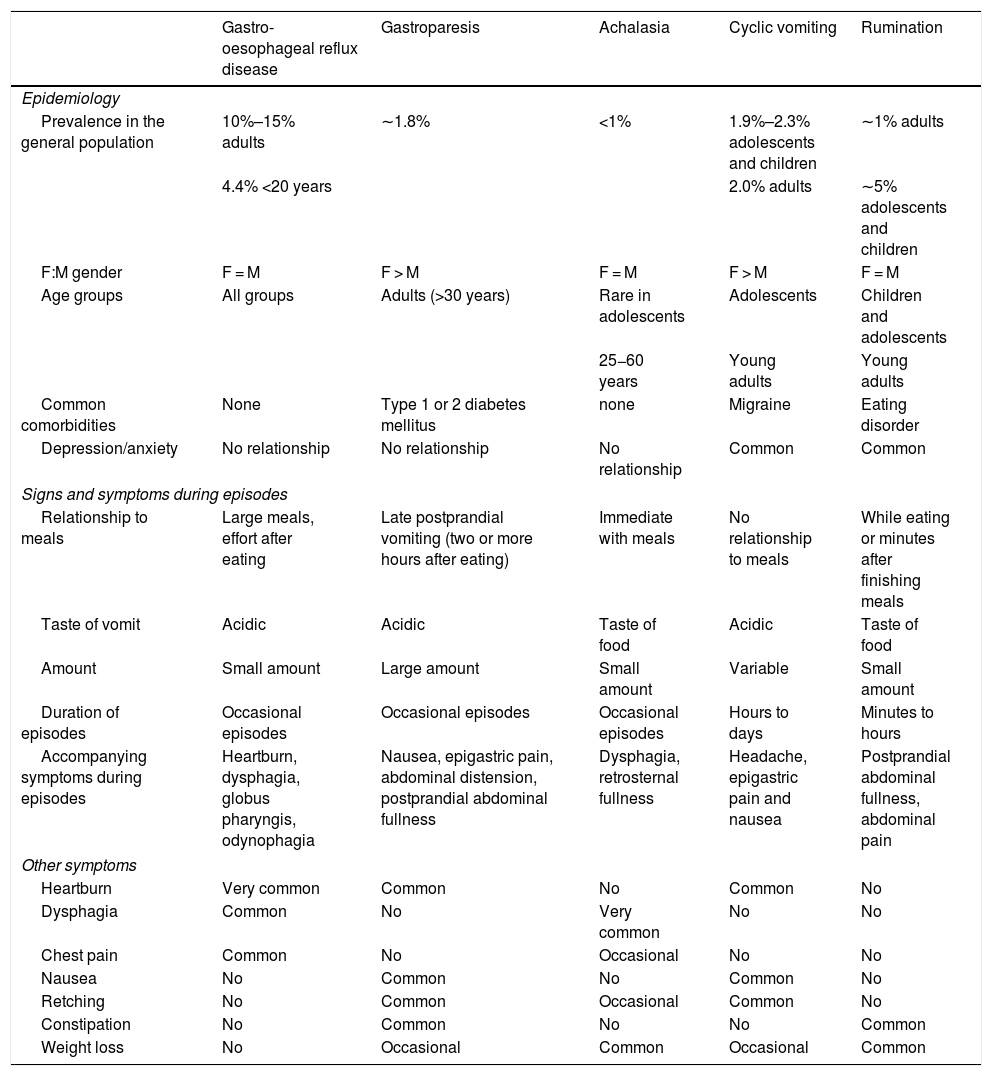

Patients with rumination syndrome describe their symptoms as "vomiting". Tests to evaluate disorders that involve chronic vomiting, such as upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy, intestinal transit studies and laboratory studies, usually yield inconclusive results.35 Rumination syndrome shares characteristics with other gastrointestinal disorders, especially GORD; gastro-oesophageal junction disorders such as achalasia; and disorders with nausea and vomiting, including gastroparesis and cyclic vomiting. Table 1 summarises the clinical characteristics that distinguish the above-mentioned disorders. The presence of oesophagitis in endoscopic studies is uncommon in patients with rumination, but it does not rule out the diagnosis.3 In fact, in a study conducted by Kessing et al.,29 episodes of gastro-oesophageal reflux were among the triggers of rumination in the patients studied. As mentioned, many patients with GORD refractory to treatment have rumination syndrome. It is important to be aware that these two entities may coexist, so that invasive treatments such as anti-reflux surgery may be avoided in patients with rumination syndrome.

Clinical characteristics of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastroparesis, achalasia, cyclic vomiting and rumination.

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Gastroparesis | Achalasia | Cyclic vomiting | Rumination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | |||||

| Prevalence in the general population | 10%–15% adults | ∼1.8% | <1% | 1.9%–2.3% adolescents and children | ∼1% adults |

| 4.4% <20 years | 2.0% adults | ∼5% adolescents and children | |||

| F:M gender | F = M | F > M | F = M | F > M | F = M |

| Age groups | All groups | Adults (>30 years) | Rare in adolescents | Adolescents | Children and adolescents |

| 25−60 years | Young adults | Young adults | |||

| Common comorbidities | None | Type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus | none | Migraine | Eating disorder |

| Depression/anxiety | No relationship | No relationship | No relationship | Common | Common |

| Signs and symptoms during episodes | |||||

| Relationship to meals | Large meals, effort after eating | Late postprandial vomiting (two or more hours after eating) | Immediate with meals | No relationship to meals | While eating or minutes after finishing meals |

| Taste of vomit | Acidic | Acidic | Taste of food | Acidic | Taste of food |

| Amount | Small amount | Large amount | Small amount | Variable | Small amount |

| Duration of episodes | Occasional episodes | Occasional episodes | Occasional episodes | Hours to days | Minutes to hours |

| Accompanying symptoms during episodes | Heartburn, dysphagia, globus pharyngis, odynophagia | Nausea, epigastric pain, abdominal distension, postprandial abdominal fullness | Dysphagia, retrosternal fullness | Headache, epigastric pain and nausea | Postprandial abdominal fullness, abdominal pain |

| Other symptoms | |||||

| Heartburn | Very common | Common | No | Common | No |

| Dysphagia | Common | No | Very common | No | No |

| Chest pain | Common | No | Occasional | No | No |

| Nausea | No | Common | No | Common | No |

| Retching | No | Common | Occasional | Common | No |

| Constipation | No | Common | No | No | Common |

| Weight loss | No | Occasional | Common | Occasional | Common |

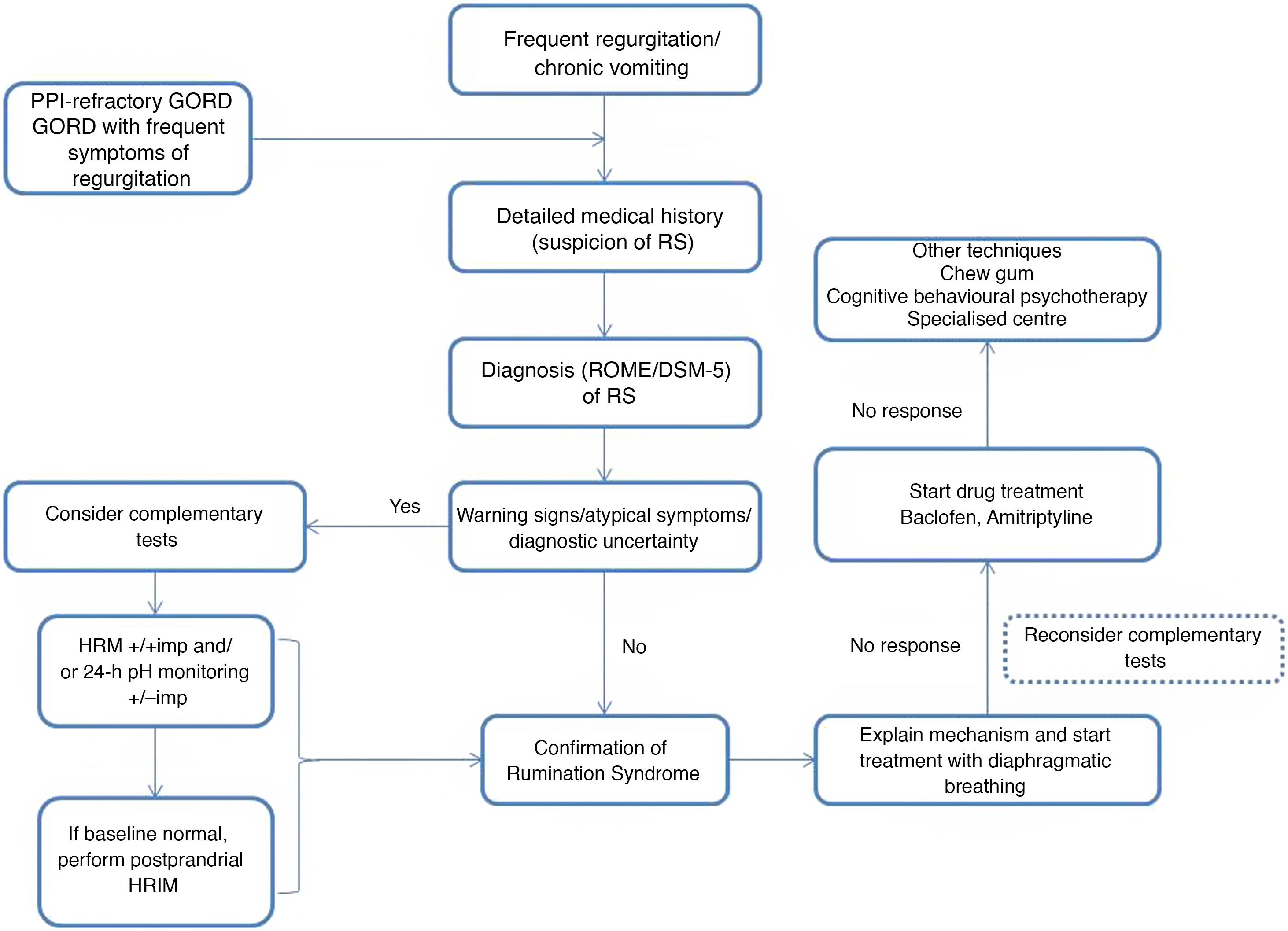

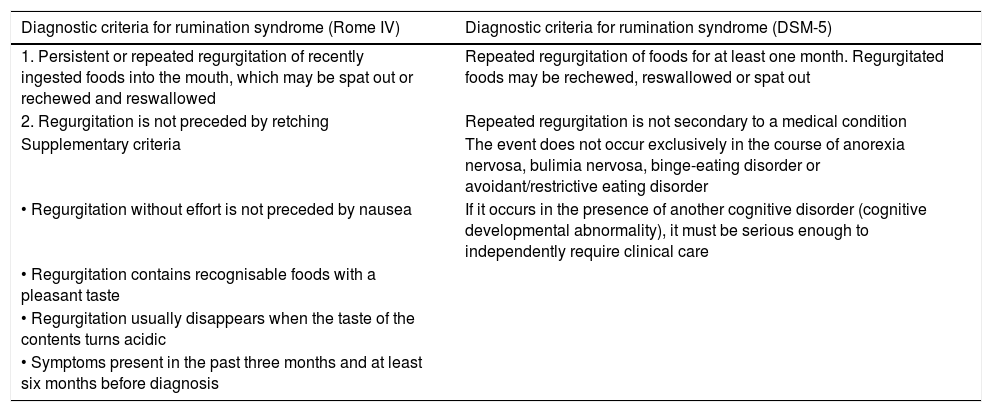

Rumination syndrome is clinically diagnosed. A comprehensive medical history on the characteristics of the symptoms must be taken. It is essential to pose questions to both the patient and the patient's immediate family, especially when caring for minor patients. The Rome IV4 and DSM-55 criteria set out in Table 2 are useful. The Rome criteria specify that diagnostic tests to rule out an organic disorder are not essential when the clinical diagnostic criteria are met. It should be noted that, in clinical practice, observation of patient behaviour is useful when the patient is exposed to foods that cause symptoms, even though this point is not taken into consideration in the diagnostic algorithms. However, due to a general lack of awareness of the disease, patients are often subjected to a battery of invasive tests, such as upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy and radiological studies,23 resulting in a diagnostic delay ranging from 2.7 to 4.9 years.24

Diagnostic criteria for rumination syndrome according to the Rome IV and DSM-5 criteria.

| Diagnostic criteria for rumination syndrome (Rome IV) | Diagnostic criteria for rumination syndrome (DSM-5) |

|---|---|

| 1. Persistent or repeated regurgitation of recently ingested foods into the mouth, which may be spat out or rechewed and reswallowed | Repeated regurgitation of foods for at least one month. Regurgitated foods may be rechewed, reswallowed or spat out |

| 2. Regurgitation is not preceded by retching | Repeated regurgitation is not secondary to a medical condition |

| Supplementary criteria | The event does not occur exclusively in the course of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder or avoidant/restrictive eating disorder |

| • Regurgitation without effort is not preceded by nausea | If it occurs in the presence of another cognitive disorder (cognitive developmental abnormality), it must be serious enough to independently require clinical care |

| • Regurgitation contains recognisable foods with a pleasant taste | |

| • Regurgitation usually disappears when the taste of the contents turns acidic | |

| • Symptoms present in the past three months and at least six months before diagnosis |

There are various complementary tests of motility with patterns suggestive of rumination syndrome. The indications for performing complementary tests in patients with suspected rumination syndrome are: the presence of uncommon symptoms in rumination such as dysphagia or heartburn, the persistence of many symptoms despite initial treatment and the need to demonstrate the origin of the symptoms to patients and their families.23 One of the main limiting factors restricting the use of such tests is their limited availability, as they tend to be concentrated at leading centres and it takes time to perform and interpret them.

For diagnosis, four types of tests are available; two of them are complex and limited to few centres. One of them is gastrointestinal manometry, which detects a generalised increase in intra-abdominal pressure, translating to a simultaneous pressure peak along the stomach and small intestine (R wave).37 However, it is a complex, uncomfortable and invasive test available at very few highly specialised centres; this has such negative repercussions for its availability that it has now lapsed into disuse.

Another test is electromyography, which is used to directly visualise the rumination mechanism and observe, during episodes of regurgitation, an abrupt, simultaneous increase in the activity of the intercostal muscles and the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, associated with the phenomena of thoracic suction and abdominal compression, respectively. This process is correlated with episodes of regurgitation.24 Limited access to this test must be cited as a disadvantage thereof.

The other two tests used for objective diagnosis of rumination syndrome are oesophageal high-resolution impedance manometry (HRIM) and 24-h ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring. It is important to note that these tests are validated in particular for diagnosing GORD, and so their results should be interpreted with caution.

HRIM simultaneously evaluates the directionality of the movement of fluid or gas in the body of the stomach and pressure changes in cavities and sphincters.29 Postprandial HRIM serves to assess the manometric response to a potentially aversive gastrointestinal stimulus and consists of a standard study subsequent to food intake.12 Unlike episodes of gastro-oesophageal reflux, episodes of rumination are characterised by an increase in gastric pressure in excess of 30 mmHg, which distinguishes the two entities.29 Characteristically, intragastric pressure increases immediately after swallowing begins: it is possible to observe, concomitantly in the impedance channel, the retrograde movement of the bolus.38 In some cases, manometric abnormality is only seen to be triggered following intake of solid food and not during the standard protocol for HRIM with the multiple swallow test;39 hence, baseline HRIM seems less useful for distinguishing rumination syndrome from GORD. However, there are no standardised protocols for evaluating suspected rumination syndrome.

Twenty-four-hour ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring using a multichannel catheter distinguishes the direction and acidity of the gastric contents, which move proximally towards the oesophagus. Yadlapati et al.12 studied a cohort of 94 patients diagnosed with PPI-refractory GORD using postprandial oesophageal HRIM and 24-h ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring, and reclassified patients based on their results: 76% of cases had an abnormal postprandial manometric pattern and 20% of them met criteria for rumination syndrome. Under this premise, Nakagawa et al.40 designed a scoring system for rumination syndrome used in patients with a provisional diagnosis of PPI-refractory GORD, who were studied with 24-h pH/impedance monitoring. This scoring system served to diagnose rumination syndrome in 46% of patients with PPI-refractory GORD and to distinguish it from persistent regurgitation with high reliability (sensitivity 91.7% and specificity 78.6%). Notably, ruminant patients had more episodes of non-acidic reflux in the early postprandial period with higher oesophageal movement than patients with PPI-refractory GORD (Figs. 1 and 2).

Pathophysiological mechanism of rumination. Food intake initiates a conditioned response, which consists of involuntary contraction of the muscles of the abdominal wall (A), an increase in intra-abdominal pressure and contraction of the intercostal muscles (thoracic suction) (B), associated with relaxation of the diaphragm, which enables reflux of recently ingested foods from the stomach to the mouth (C).

Treatment options in rumination syndrome can be divided into behavioural therapy, drug treatment and surgery. Information on efficacy, safety and long-term results is limited, and most of the evidence to date has come from observational studies, retrospective studies and case series.35

The success of behavioural therapy depends on a detailed explanation of the disease and the underlying pathophysiological mechanism. It should be noted that most patients are unaware and unconscious of the process that leads to the episode of regurgitation, which is determined by coordination of different muscle groups, contributed to by the speed and facility of the manoeuvre leading to regurgitation.3 At present, diaphragmatic breathing (with or without biofeedback) is considered a first-line treatment due to the high quality of the evidence on its use, ease of outpatient implementation and low cost.31

The evidence to date has shown diaphragmatic breathing to be an effective treatment in decreasing episodes of regurgitation. Diaphragmatic breathing consists of placing one hand on the chest and the other on the abdomen during breathing.41 The patient is instructed in moving the abdomen outwards during thoracic breathing and in maintaining the position of the chest, using the hand on the chest to make sure that it remains as still as possible. Breaths should be slow and complete, with an average of six to eight respirations per minute. It is recommended that diaphragmatic breathing be practised for 15 min after each meal; it should also be done between meals if the patient has any episodes of regurgitation, to rehabilitate the rumination. In an observational study with 16 patients guided with postprandial oesophageal HRIM, diaphragmatic breathing led to a drop in gastric pressure and an increase in gastro-oesophageal pressure, translating to lower numbers of postprandial regurgitation events.30 These findings indicate that increased gastro-oesophageal junction pressure plays a role in the therapeutic effects of behavioural therapy in rumination syndrome. The limitation was that the episodes of rumination recurred when the patients resumed their usual breathing pattern.

Rehabilitation therapy using biofeedback-guided diaphragmatic breathing with electromyography decreases the activity of the intercostal musculature and of the musculature of the anterior wall and achieves a reduction in episodes of regurgitation.24 The soundest evidence comes from a randomised study with 24 patients that demonstrated the superiority of electromyography-guided biofeedback compared to placebo.42 All patients in the intervention group received three sessions over a 10-day period. Those who received biofeedback not only effectively learned to reduce the activity of the intercostal muscles and muscles of the anterior wall, but also showed a significant long-term decrease in rumination events.

To date, no studies directly comparing diaphragmatic breathing with or without biofeedback have been conducted. Given the low availability of biofeedback in most clinical practice settings, some authors have recommended taking a stepwise approach to treatment and reserving biofeedback for cases with partial response or failure to diaphragmatic breathing.31

Due to the pathophysiological mechanism of rumination syndrome, drugs that improve gastric accommodation or emptying or that increase lower oesophageal sphincter tone may be helpful.43

Baclofen is a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonist that acts by increasing lower oesophageal sphincter tone and suppressing transient relaxation of that sphincter. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with 20 patients, baclofen 10 mg 3 times daily was associated with a modest decrease in episodes of regurgitation seen in postprandial oesophageal HRIM, probably due to its effects on the lower oesophageal sphincter.44 In an open-label study, 12 patients with rumination syndrome completed one week of treatment with baclofen, with a marked reduction in their episodes of postprandial regurgitation.43 The long-term impact of baclofen with regard to clinical efficacy and tolerability is unknown. In clinical practice, baclofen's safety profile may severely limit its use, especially in the elderly, who is more likely to experience its adverse effects (sedation, drowsiness, confusion, dizziness, fatigue and insomnia).

An open-label study with 21 patients evaluated the effects of psychotherapy with levosulpiride, a selective dopamine D2 receptor antagonist with prokinetic activity, over an eight-month period.45 Just 38% of patients showed clinical improvement, compared to 48% who experienced no changes and 14% whose symptoms worsened.

There are no controlled clinical studies evaluating the role of neuromodulators as a sole treatment in rumination syndrome. Just one uncontrolled prospective study46 evaluated the adjuvant effects of tricyclic antidepressants plus behaviour therapy, with promising results. The role of neuromodulators is better established in the management of comorbid conditions, such as psychiatric disorders, highlighting the probable effects on the phenomenon of visceral hypersensitivity.31 Anecdotally, the benefits of chewing gum have been reported in two cases in the paediatric and adolescent population with psychiatric comorbidity.47 A small case series reported resolution of symptoms in five patients with rumination syndrome refractory to medical treatment and behavioural therapy, who were treated by means of Nissen fundoplication.48 Clinical improvement has also been reported with subtotal gastrectomy in a single refractory case.49 However, in view of the absence of high-quality information from randomised clinical studies, as well as the risks inherent to major surgery, surgical treatment is not included in the therapeutic algorithm for rumination syndrome, and its role should be limited to research.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alcala-Gonzalez LG, Serra X, Barba E. Síndrome de rumiación, revisión crítica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:155–163.