Background/Objective: Literature shows that practicing physical activity improves the general health and quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities. However, there is little empirical research on the specific benefits physical activity provides and to what extent these benefits occur. The goal of this study was to examine the impact of perceptions of physical activity and the individualized support on each of eight quality of life-related domains and three higher-order quality of life factors. Method: The sample consisted of adults with intellectual disability (n=529), their assigned professionals (n=522), and a family member (n=462). Most participants attended day and residential services, and we applied the Personal Outcomes Scale and the Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale to all of them. Results: The structural model parameter estimation showed high values, especially for the factor of well-being. These data allowed us to confirm that perceptions of physical and individualized supports in the field of physical activity act as predictors of quality of life improvement. Conclusions: The results suggest that organizations devoted to enhancing personal outcomes should include physical activity in their programs, and revise both their own services and the use of physical activity resources available in the community.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: Practicar actividad física mejora la salud general y la calidad de vida de las personas con discapacidades intelectuales. Existe poca investigación sobre los beneficios específicos de la actividad física y hasta qué punto se dan. El objetivo de este estudio es examinar el impacto de las percepciones sobre la actividad física y el apoyo individualizado sobre los dominios que definen calidad de vida. Método: La muestra se compuso de 529 adultos con discapacidad intelectual, sus profesionales de referencia (n=522) y un familiar (n=462). La mayoría de los participantes asistían a servicios de día y residenciales, y se les aplicó la Escala de Resultados Personales y la Escala de Necesidades de Apoyo y Estrategias para la Actividad Física. Resultados: Se propone un modelo estructural para analizar la relación entre constructos que mostró valores altos, sobre todo para el factor del bienestar. Así, las percepciones sobre la actividad física y los apoyos individualizados en el campo de la actividad física actúan como predictores de la mejora de la calidad de vida. Conclusiones: Se sugiere que las organizaciones dedicadas a mejorar los resultados personales deberían incluir la actividad física en sus programas comunitarios.

In the field of intellectual disability (ID) the quality of life (QoL) concept has become a framework for the enhancement of personal outcomes as well as a basis for quality services and program accountability (Reinders & Schalock, 2014; Schalock, Gardner, & Bradley, 2007; Schalock, Verdugo, Bonham, Fantova, & van Loon, 2008). This study focused on components and premises of QoL outcomes widely discussed (e.g., Buntinx & Schalock, 2010; Luckasson & Schalock, 2013; Schalock et al., 2007). The purpose was to examine the relationship between physical activity (PA) and personal quality of life-related outcomes. These outcomes are understood as “person-defined and valued aspirations. Personal outcomes are generally defined in reference to QoL domains and indicators” (Schalock, Verdugo et al., 2008, p. 278) and can be used to assess the intervention of the supports and services that people with ID receive (Luckasson & Schalock, 2013; Schalock & Verdugo, 2012a; van Loon et al., 2013). In accordance with the aforementioned authors, we have kept in mind the fact that the improvement of QoL-related personal outcomes takes place when development opportunities as well as individualized supports are fostered in the individual's life environments. Hence, the research question addressed in this article is how PA impacts QoL-related personal outcomes.

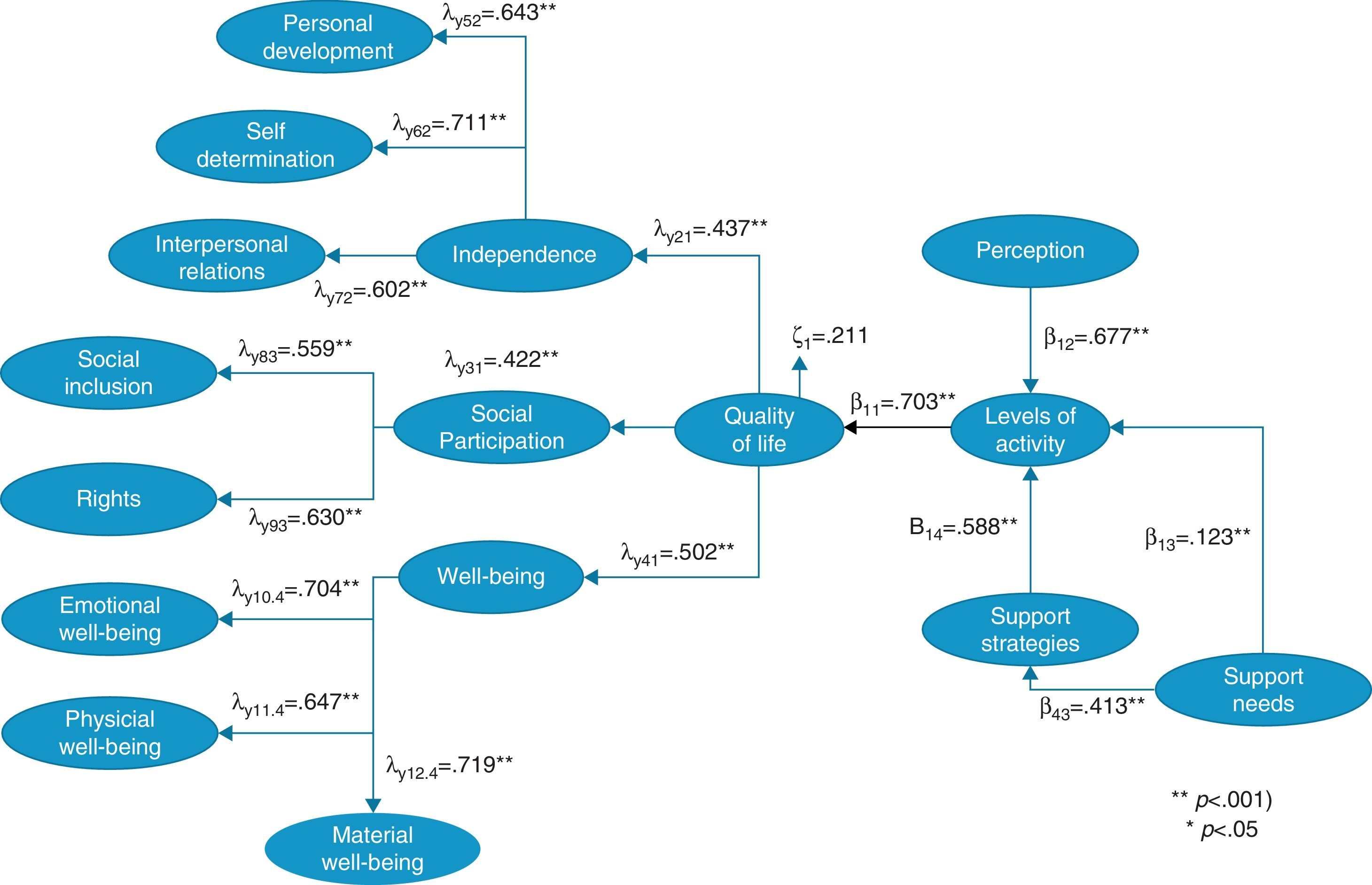

Quality of Life-related personal outcomesCurrently, the QoL construct provides a framework to evaluate personal outcomes. The assessment of QoL-related personal outcomes is based on three factors and eight domains validated in a series of cross-cultural studies: (1) Independence, comprised of Personal Development and Self-determination; (2) Social Participation, which includes Interpersonal Relations, Social Inclusion, and Rights; and (3) Well-being, which encompasses Emotional well-being, Physical well-being, and Material well-being (Jenaro et al., 2005; Schalock et al., 2005; Wang, Schalock, Verdugo, & Jenaro, 2010). The measurement of personal outcomes considers four QoL assessment principles proposed by a group of international experts of this field (Schalock et al., 2002). The QoL assessment: (a) includes the extent to which the person has life experiences they value; (b) identifies the dimensions contributing to a full life with connections between the different environments; (c) considers the physical, social, and cultural contexts which are important for the person; and (d) comprises measurements of both common experiences for all people as well as personal ones for each individual. For a correct assessment of personal outcomes, it is necessary to have measurement instruments with satisfactory psychometric properties, and ones that are based on the previously mentioned QoL empirically validated model composed of factors and domains. As stated in the QoL assessment principles, evaluating QoL involves the combination of the subjective well-being measurement (including individual preferences) and the objective circumstances and life experiences (Cummins, 2005; Schalock et al., 2007). The Personal Outcomes Scale (POS; van Loon, Van Hove, Schalock, & Claes, 2008) was developed on the basis of the eight domain model described above. In this study, we used the Spanish POS adaptation (Carbó-Carreté, Guàrdia-Olmos & Giné, 2015). The results obtained from this scale allow us to examine the impact of PA at an individual level. In addition, these results can be a guide for improvement at the organizational level as well as assist in the monitoring of socially inclusive practices in the PA field.

Physical activity in people with IDThe literature reveals that PA improves the general health conditions and QoL of people with ID (Bartlo & Klein, 2011; Heller, McCubbin, Drum, & Peterson, 2011). More specifically, it has been shown that PA (a) helps mitigate anxiety levels (Carraro & Gobbi, 2012) and enhances good physical appearance and the establishment of social relationships (Frey, Buchanan, & Rosser Sandt, 2005; Maneiro, Prado, & Soidan, 2014); (b) decreases maladaptive behaviors; and (c) improves the perception of well-being and functional skills (Carmeli, Zinger-Vaknin, Morad, & Merrick, 2005; Heller et al., 2011). These improvements have been measured via different methods. For example, some studies have used adapted measurement scales for people with ID (Carmeli et al., 2005), and others have used in-depth interviews, diaries, and informal observations (Frey et al., 2005). Systematic reviews have endorsed these results (Heller et al., 2011; Hutzler & Korsensky, 2010). In addition, positive physical effects of PA have been well documented in persons with ID by using fitness tests. Several studies have reported large positive results on cardiovascular endurance (Rimmer, Heller, Wang, & Valerio, 2004), as well as significant increases in muscle strength and balance (Carmeli et al., 2005; Shields et al., 2013).

Despite the demonstrated benefits of PA, certain articles note that individuals with ID show low levels of PA, insufficient to reach the health levels expected (Fernhall & Pitetti, 2001; Temple, Frey, & Stanish, 2006). To improve their living conditions, people with ID should engage in the advisable level of PA, which is five or more thirty-minute moderate PA sessions per week, according to the World Health Organization, WHO (2009). Given these unsatisfactory low levels, a large number of articles have focused on identifying the elements hindering PA practice in this population. Most of the articles reviewed identify factors such as the limitations in accessing PA practices due to transport difficulties, economic cost, lack of personalized support, lack of choices, and lack of community PA programs available (Frey et al., 2005; Hsieh, Heller, Bershadsky, & Taub, 2015; Howie et al., 2012; Mahy, Shields, Taylor, & Dodd, 2010; van Schijndel-Speet, Evenhuis, van Wijck, van Empelen, & Echteld, 2014).

Considering this reality, it becomes logical to ponder what the main needs in the field of PA are. The literature provides studies addressing this question. One remarkable work is the development of the self-efficacy and social support scales, which were developed to evaluate their role in leisure PA (e.g., Lee, Peterson, & Dixon, 2010). Recently, the Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale (Carbó-Carreté, Guàrdia-Olmos, & Giné, in press) was developed and is a useful tool to design and provide the support needed by people with ID to practice PA satisfactorily.

QoL-Related Physical Activity: An integrative structural equation modelAs mentioned previously, this study focused on the relationship between the levels of PA and the QoL of people with ID. The eight domain QoL model validated (Jenaro et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010) provides the appropriate framework to examine the impact of personal and environmental factors on the QoL-related personal results (Claes, van Hove, Vandevelde, van Loon, & Schalock, 2012; Reinders & Schalock, 2014; Schalock et al., 2007). This understanding is closely related to the ecologic view of disability, which explains human functioning according to the mismatch between the individual's capacities and the environment's requirements. Minimizing the discrepancy between these two elements implies identifying and providing the individualized support needed to enhance the person's performance (Luckasson & Schalock, 2013). Accordingly, the support paradigm has evolved as a key component in aligning individual support needs and the actual support strategies received to enhance personal outcomes (Buntinx & Schalock, 2010; Schalock & Verdugo, 2012b). The variable ‘support strategies’ represents what is understood as a System of Supports defined as “[t]he planned and integrated use of individualized support strategies and resources that encompass the multiple aspects of human performance in multiple settings” (Schalock & Luckasson, 2013 p. 91). This variable acts as a mediator, given that it conditions the impact someone's support needs may have.

According this framework, we proposed a model that includes the level of PA and the QoL. The level of PA is obtained using the individual's perceptions and their relation to the support strategies they receive. The perceptions and goals have to be examined according to the support needs to design Individualized Support Plans (ISP) to achieve personal outcomes (Schalock, Bonham & Verdugo, 2008). Thus, the PA related data allows us to examine the impact of the three factors and eight domains of QoL described above. Depending on to what extent the strategies meet the support needs, they will have a greater or smaller impact on the level of PA. Based on what has been set forth so far, we can hypothesize that this will be a significant, positive impact.

To examine the proposed model, we used two measurement instruments. For the personal outcome measures, we administered the Spanish adaptation of the Personal Outcomes Scale (Carbó-Carreté et al., 2015), and to evaluate the level of PA, we applied the Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale (Carbó-Carreté et al., in press). These two instruments are described in detail in the following section.

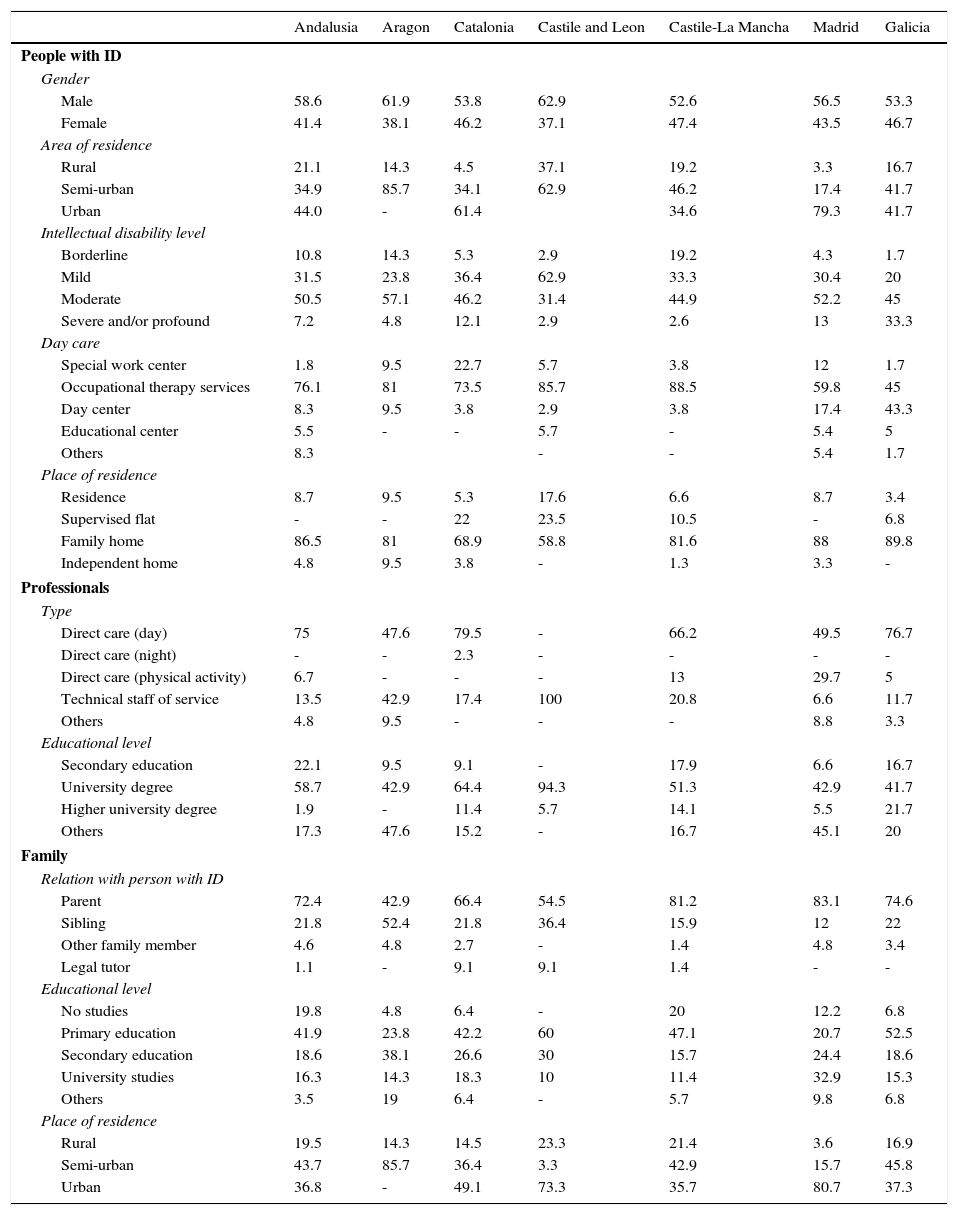

MethodParticipantsThe sample consisted of a total of 529 people with ID (296 men and 233 women), with Mage= 35.03, SD= 10.82, age range: 16-66, who came from seven Autonomous Communities in Spain: Andalusia (20.9%), Aragon (4%), Catalonia (25%), Castile and León (6.6%), Castile-La Mancha (14.8%), Madrid (17.4%), and Galicia (11.7%). Out of the total sample, 84.9% engaged in PA and, out of those who did not, 73% acknowledged no health or mobility problems preventing them from engaging in PA. Professionals (n=522) and family members (n=462) participated as well.

In this study, accidental, non-randomized sampling was carried out in every Autonomous Community. The following table (Table 1) shows the main descriptive data regarding the individual with ID, the professional and the family member who participated for every community. Given the characteristics of the population sampled, the inclusion criterion was that the level of severity of the limitations or other health problems the person with ID presented did not prevent them from conducting some PA.

Descriptive data of people with ID, professionals and family.

| Andalusia | Aragon | Catalonia | Castile and Leon | Castile-La Mancha | Madrid | Galicia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People with ID | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 58.6 | 61.9 | 53.8 | 62.9 | 52.6 | 56.5 | 53.3 |

| Female | 41.4 | 38.1 | 46.2 | 37.1 | 47.4 | 43.5 | 46.7 |

| Area of residence | |||||||

| Rural | 21.1 | 14.3 | 4.5 | 37.1 | 19.2 | 3.3 | 16.7 |

| Semi-urban | 34.9 | 85.7 | 34.1 | 62.9 | 46.2 | 17.4 | 41.7 |

| Urban | 44.0 | - | 61.4 | 34.6 | 79.3 | 41.7 | |

| Intellectual disability level | |||||||

| Borderline | 10.8 | 14.3 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 19.2 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Mild | 31.5 | 23.8 | 36.4 | 62.9 | 33.3 | 30.4 | 20 |

| Moderate | 50.5 | 57.1 | 46.2 | 31.4 | 44.9 | 52.2 | 45 |

| Severe and/or profound | 7.2 | 4.8 | 12.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 13 | 33.3 |

| Day care | |||||||

| Special work center | 1.8 | 9.5 | 22.7 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 12 | 1.7 |

| Occupational therapy services | 76.1 | 81 | 73.5 | 85.7 | 88.5 | 59.8 | 45 |

| Day center | 8.3 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 17.4 | 43.3 |

| Educational center | 5.5 | - | - | 5.7 | - | 5.4 | 5 |

| Others | 8.3 | - | - | 5.4 | 1.7 | ||

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Residence | 8.7 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 17.6 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 3.4 |

| Supervised flat | - | - | 22 | 23.5 | 10.5 | - | 6.8 |

| Family home | 86.5 | 81 | 68.9 | 58.8 | 81.6 | 88 | 89.8 |

| Independent home | 4.8 | 9.5 | 3.8 | - | 1.3 | 3.3 | - |

| Professionals | |||||||

| Type | |||||||

| Direct care (day) | 75 | 47.6 | 79.5 | - | 66.2 | 49.5 | 76.7 |

| Direct care (night) | - | - | 2.3 | - | - | - | - |

| Direct care (physical activity) | 6.7 | - | - | - | 13 | 29.7 | 5 |

| Technical staff of service | 13.5 | 42.9 | 17.4 | 100 | 20.8 | 6.6 | 11.7 |

| Others | 4.8 | 9.5 | - | - | - | 8.8 | 3.3 |

| Educational level | |||||||

| Secondary education | 22.1 | 9.5 | 9.1 | - | 17.9 | 6.6 | 16.7 |

| University degree | 58.7 | 42.9 | 64.4 | 94.3 | 51.3 | 42.9 | 41.7 |

| Higher university degree | 1.9 | - | 11.4 | 5.7 | 14.1 | 5.5 | 21.7 |

| Others | 17.3 | 47.6 | 15.2 | - | 16.7 | 45.1 | 20 |

| Family | |||||||

| Relation with person with ID | |||||||

| Parent | 72.4 | 42.9 | 66.4 | 54.5 | 81.2 | 83.1 | 74.6 |

| Sibling | 21.8 | 52.4 | 21.8 | 36.4 | 15.9 | 12 | 22 |

| Other family member | 4.6 | 4.8 | 2.7 | - | 1.4 | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| Legal tutor | 1.1 | - | 9.1 | 9.1 | 1.4 | - | - |

| Educational level | |||||||

| No studies | 19.8 | 4.8 | 6.4 | - | 20 | 12.2 | 6.8 |

| Primary education | 41.9 | 23.8 | 42.2 | 60 | 47.1 | 20.7 | 52.5 |

| Secondary education | 18.6 | 38.1 | 26.6 | 30 | 15.7 | 24.4 | 18.6 |

| University studies | 16.3 | 14.3 | 18.3 | 10 | 11.4 | 32.9 | 15.3 |

| Others | 3.5 | 19 | 6.4 | - | 5.7 | 9.8 | 6.8 |

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Rural | 19.5 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 23.3 | 21.4 | 3.6 | 16.9 |

| Semi-urban | 43.7 | 85.7 | 36.4 | 3.3 | 42.9 | 15.7 | 45.8 |

| Urban | 36.8 | - | 49.1 | 73.3 | 35.7 | 80.7 | 37.3 |

- -

Personal Outcomes Scale–Spanish Adaptation. The Personal Outcomes Scale–Spanish adaptation (Carbó-Carreté et al., 2015) is an adaptation of the Personal Outcomes Scale (van Loon et al., 2008) that aims to assess QoL in people with ID on the basis of the eight domain QoL model (Schalock & Verdugo, 2002), which was arranged into three higher-order factors: independence, social participation, and well-being (Wang et al., 2010). Because we had adapted the original scale for this study, expert translations conducted a back translation process before its administration. We also carried out a pilot test with a sample of 77 people with ID and their professionals whom we did not include in the final sample. This prior analysis showed a good reliability level in terms of internal consistency (α=.85 to α=.89) for the different factors and sources of information, and of appropriate discriminability values for the items (in all cases>.54). Afterwards, we validated the Spanish POS adaptation in the three information sources, each one of which was composed of the same domain-reference indicator items: (a) self-report, where the individual answered on his/her own; therefore, this assessed the subjective perspective of QoL; (b) report by professional, which assessed the individual's experiences and circumstances from the point of view of direct care staff or a service technician; and (c) report by family, where the indicators were given scores from a family member's perspective. If the person could not answer on his/her own, we only used the professional's report and the family member's report. In each version six items evaluate each QoL domain and every item is assessed through the use of a 3-point Likert scale. Likert-type scales are easily comprehensible for the interviewed and provide an efficient and reliable method for psychometric assessments of personal outcomes. Scores are obtained through an interview that is conducted by an interviewer who has previous training regarding the theoretical model of the scale and its proper administration. For the reports by the professional and the family member, the respondents needed to have known the person with ID for at least 3 months and needed to have had the opportunity to observe him/her in one or more environments over a period of 3 to 6 months. Outcomes were obtained for each of the eight domains and the three factors. For every domain, the sum of all of the scores from the 6 items is obtained by using the following metric: (3)=always, (2)=sometimes, and (1)=rarely or never. After summing the domains of every factor, a final score is calculated for each factor. The Spanish POS adaptation (Carbó-Carreté et al., 2015) is consistent with the multidimensionality of the QoL construct examined and with the three second-order factors. The reliability study provides appropriate values for the first-order domains and, particularly, for the second-order factors, with α values higher than .82. Moreover, the construct validity analysis provides an adjustment of the theoretical model with regard to the three sources of information, particularly regarding the professionals’ assessments. Pearson's correlations between factors are also coherent in the studied model. The lowest values for the first-order factor were between rights and social inclusion domains (r= 32, p<.001), and the highest between interpersonal relations and personal development (r=73, p<.001), both correlations in the self-report answered by the individual with ID. In the second-order factor the lowest values were between well-being and social participation (r=42, p<.001) for the self-report and the highest between social participation and independence (r=77, p<.001) for the family report.

- -

Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale. The Support Needs and Strategies Scale (Carbó-Carreté et al., in press) examines two factors: (1) the support needs of people with ID to allow them to adequately engage in PA and (2) the strategies provided for supporting these needs. This scale contains 15 dichotomic items for each factor. To ensure an accurate assessment of the presence of such strategies, the items are directly related to the support needs (e.g., If you want to engage in PA or a sport activity during your leisure time, do you need someone to go with you? If so, is there someone (e.g., staff, family member or friend) who can go with you?). The items pertaining to the support strategies are based on the elements organized in the support system, which encompass the aspects present in the multiple environments where the person lives (Schalock & Verdugo, 2012b). To obtain a thorough view of these two factors, this scale had three versions, one for each type of informer: the individual with ID, the professional, and the family member. Each version of this scale was administered by a professional interviewer who was familiar with the instrument and was able to answer any questions. This instrument features two descriptive scales that provide necessary data to describe the PA practice of people with ID. On one hand, the Level of Physical Activity Scale evaluates the frequency, the duration, and the intensity of PA based on 11 multiple-choice items. Five of the eleven items form a scale (items 2, 5, 7, 8, and 9) and the remaining items are descriptive variables. On the other hand, the Perceptions scale comprises nine dichotomic items that examine the perception, knowledge, and motivation of the individuals regarding their PA. This scale also examines factors pertaining to PA-related motivation and satisfaction in the individuals and is administered via an interview with the individual with ID. As the items are dichotomic, we considered the summation of the number of items with an affirmative answer a direct estimation of the positive perceptions of PA engagement. This instrument has acceptable psychometric properties that were analyzed previously (Carbó-Carreté et al., in press). The reliability values obtained for each of the scales and for each information source were α values between .70 and .80. A construct validity analysis indicated that the theoretical model fit the three information sources. Discrepancy indicators are used to examine the support needs and the strategies provided. In addition, a congruence index is used to analyze the degree of agreement between the three informers. To measure concurrent validity, we examined the correlations among scales and indicators. Regarding the values for the support needs and strategy indicators, the results showed highly significant correlations between support needs and each informer's assessment with regard to the strategies they received (r=.90, p<.001 for the individuals with ID and the family members, and r=.85, p<.001 for the professionals). The positive correlation between the Level of PA and Perceptions scales (r=.16, p<.001) confirmed that increased knowledge and a positive perception of PA favor the greater presence of related levels.

The service organizations were asked to participate through the Spanish Confederation of Organizations for the Persons with Intellectual Disability (FEAPS) and with the logistic support of each Autonomous Community's delegation. The organizations that agreed to take part in the research offered day services (i.e., special work centers, occupational therapy, and day centers) and most also had residential services (i.e., supervised flats and residences) for adult individuals with ID. The professionals who showed interest in being interviewers received specific information on the administration of the POS and the Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale. These training sessions took place at the FEAPS office in each Autonomous Community. They were taught by the authors of the project, who also gave support by answering questions throughout the application of the questionnaires. To obtain the necessary data for the goals set, we required the interviewers to apply the POS and the PA-related scale to the same sample. With the POS, we asked them to administer both parts of the Scale, that is, each interviewer applied the self-report part to the person with ID and the other parts to a professional and a family member. In total we asked the interviewer to apply the scales to the three informants for the POS. As for the Support Needs and Strategies for PA, the interviewers were asked to interview the same participants as they did for the POS. The same interviewer applied all scales to each participant. Moreover, the person acting as a professional was also asked to do so for the whole scale (for the Levels of PA scale and for the professionals’ version of the Support Needs and Strategies Scale). From a total of 670 eligible participants, 529 responded to complete questionnaires (without missing data) by following the established instructions. In addition to the questionnaires, informed consent forms were provided for all of the participants to read and sign.

Data analysisTo describe and explore the observed distribution of the variables in the model we used IBM SPSS (version 21). For structural parameter estimation, and in light of the distributions observed, we used a Maximum Likelihood solution (MLR) based on the minimization of differences (R-Σ) according to the characteristics of Mplus (5.0) (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) without any statistical correction due to the presence of missing data because all of the records were complete. We applied this estimation solution using the proposition by Ory and Mokhtarian (2010) for categorical variables, without any statistical correction due to the presence of unregistered data because all of the records were complete.

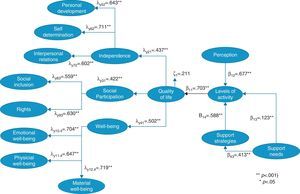

ResultsThe standardized results of each of the main structural parameters previously defined in the model are summarized in Figure 1.

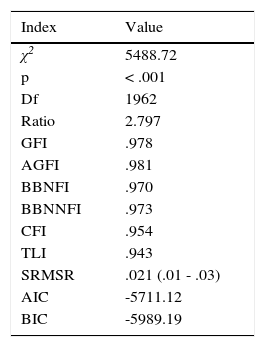

Additionally, Table 2 shows the global values of the proposed model's fit in its general form. A quick review of the values showed a good fit except for the χ2 statistic of fit, which was statistically significant (p<.001). However, the values of the ratio of χ2 estimated value and their degrees of freedom were excellent (2.797<3). The rest of the fit indices showed values between .943 to .981 and confidence intervals (95%) of standardized residuals between .01 and .03. To interpret these indices the following criteria were used: χ2/df ratio<2 (excellent); χ2/df<3 (good); χ2/df<5 (acceptable); good fit for GFI, AGFI, BBNFI, BBNNFI, CFI and TLI ≥ .90; SRMSR ≤ .05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Fit Index of Structural Equation Model of Figure 1.

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| χ2 | 5488.72 |

| p | < .001 |

| Df | 1962 |

| Ratio | 2.797 |

| GFI | .978 |

| AGFI | .981 |

| BBNFI | .970 |

| BBNNFI | .973 |

| CFI | .954 |

| TLI | .943 |

| SRMSR | .021 (.01 - .03) |

| AIC | -5711.12 |

| BIC | -5989.19 |

Note. GFI= Goodness of Fit Index, AGFI= Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index, BBNFI= Bentler Bonnet Normed Fit Index, BBNNFI= Bentler Bonnet Non Normed Fit Index, CFI= Comparative Fit Index, TLI= Tucker Lewis Index, SRMSR= Standardized Root Mean Standard Residual, AIC= Akaike Information Criteria, BIC= Bayesian Information Criteria.

A closer analysis of each of the parameters allowed us to establish some important results. The partial QoL model (as endogenous structure) was defined according to Schalock's model (Wang et al., 2010) and we obtained more than acceptable coefficients, both for the eight first-order factors (QoL domains) and for the three second-order factors (Independence, Social Participation, and Well-Being). The well-being factor was the one with the highest values (λy41=.502, p<.001) with a remarkable result in the material well-being domain (λy12.4=.719, p<.001). Apart from this, the high value obtained in Independence should also be noted, specifically in the self-determination domain (λy62=.711, p<.001). The lowest value, though only slightly so, appeared in the Social Participation factor, in the social inclusion domain (λy83=.559, p<.001), although it was deemed a significant result. The remaining coefficients were considered coherent and consistent with the examined model.

The PA level model (as an exogenous structure) determined by three variables described in the aforementioned literature showed more than acceptable results. As expected, the coefficient obtained in perceptions (β12= .677, p<.001) confirmed that the motivation for PA and knowledge of the persons themselves on the benefits of PA are essential. The direct effect of the Support strategies on the PA level also showed a statistically significant impact in the expected sense (β14= .588, p<.001). Therefore, along with the perceptions, they are the two highly significant direct effects. As for the indirect effect (β43· β14) on the level of PA derived from the Support Needs variable, it was also statistically significant (β43·β14= .243, p<.001). Lastly, the direct effect of this variable (needs) on the PA level was statistically significant but with a lesser intensity (β13= .123, p<.05). These results would favor the conception of the mediating role of the variable Support Strategies, in accordance with the papers by Farmer (2012) and Schalock, Verdugo, Gómez, and Reinders (in press).

Finally, regarding the structural model's parameter estimation, we obtained a high value (β11=.703, p<.001) that allows us to confirm that the PA variable has an impact on the QoL of the people with ID. Therefore, considering the variables, an important effect is guaranteed in each of the domains that define the QoL concept1.

DiscussionThe goal of this study was to examine the relationship between PA practice and the QoL of people with ID. The data confirmed that PA acts as an important predictor of QoL improvement. The authors assessed the PA level model by treating the perceptions and individualized supports as predicting components of QoL improvement. As for the Perceptions variable, we can confirm that it plays a relevant role in predicting the PA level of the person with ID. The results obtained, which are clearly linked to previous studies on the field at hand, show how the person's motivation and interests affect the practice of PA (Hutzler & Korsensky, 2010). These results support previous studies that emphasize the importance of conducting training programs on PA-related subjects as a complement to the PA specific sessions (Bazzano et al., 2009).

The Support Strategies variable seems to act as a mediator as it explains the relationship arising between the actual support needs and the results of the PA level. As expected, the Support Needs variable yielded a less significant value with respect to the strategies received, which is completely justified by the ecologic view of the disability and the role of individualized support for the person's functioning (Schalock & Luckasson, 2013).

Therefore, the results suggest that identifying the support needs and providing adequate strategies in the sphere of PA has an impact on the achievement of enhanced personal outcomes. The second-order factor that received the strongest impact is well-being, which is consistent with the literature reported in the field of PA (Bartlo & Klein, 2011; Heller et al., 2011; Hutzler & Korsensky, 2010). It is worth noting the importance of the domains of emotional and material well-being, both of them slightly higher than that of physical well-being. The fact that most empirically based studies contribute data on the improved physical condition (Carmeli et al., 2005; Shields et al., 2013) coul be interpreted that the other two domains do not receive the same degree of impact from PA. However, in the present study, the data clearly show that the improvement is similar in the three domains of the person's well-being.

As for the independence factor, the results obtained in the self-determination underscore a topic discussed in one of the most frequently cited papers in this field (Frey et al., 2005), which reveals that people with ID tend to choose sedentary leisure activities instead of those involving a certain amount of PA. Based on the impact of the self-determination domain, it is therefore advisable to put a special emphasis on revising the supports and orientations given to individuals with ID, since the lack of guidelines and a discouraged attitude by professionals in this field can determine AF options (Frey et al., 2005; van Schijndel-Speet et al., 2014).

The third factor, social participation, had the lowest effect, but that does not entail a smaller degree of relevance. Social inclusion is a key subject both in professional practices and social policies, and it is also present in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006), explicitly specified in article 19. The domains of social inclusion and rights are discussed in the papers dealing with the PA barriers for persons with ID, which highlight the lack of supports to access and participate in the choices available in the community (Frey et al., 2005; Mahy et al., 2010).

To our knowledge, the results obtained in the Independence and Social participation factors should be analyzed at two levels. First, it is necessary to examine the individualized supports and programs related to the area of PA supplied by the organizations. As we already mentioned, a great number of the participants in this study attended occupational therapy, and they probably carry out PA according to standard programs that fit into the organizations’ hours. Therefore, it is important that the organizations offer a PA service based on fulfilling each individual's support needs. Second, the data obtained prompt a review of the current situation regarding service accessibility in the community. As some authors discuss (e.g., Howie et al., 2012; Hsieh et al., 2015), it would be advisable to revise the choices persons with ID have to access PA facilities and community programs. These opportunities are necessary to promote social policies that defend the rights of persons with ID and social participation in the field at hand. As a consequence of all of the above, the need is justified to promote PA opportunities and programs for persons with ID in community environments, with the necessary supports, either to conduct PA in a general sense or in a more specific way.

Thus, our proposal is that data obtained through the Support Needs and Strategies for Physical Activity Scale should be included in the ISP, with the information gathered by the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS; Thompson et al., 2004) and use this information to provide individualized supports in the life activities. Additionally, like with the implementation of the ISP (van Loon, 2015), it is essential to identify what is important for the person and integrate their goals in the PA field into individualized plans. At the moment, we have no data on the funding for the provision of individualized support for PA. Future research will focus on this topic considering the previous works related to the SIS and resource allocation (Fortune et al., 2008; Giné et al., 2014).

This study has some limitations. First, the participating organizations from the different Autonomous Communities presented different levels of knowledge and application of the QoL model and of the directives defined in relation to the support paradigm. Therefore, despite having conducted specific training sessions on the theoretical foundations and the questionnaires’ administration, the degree of understanding of the items may have been different for different respondents. Second, most of the participants of the sample with ID lived with their families and there was a low presence of those living in tutored flats or independent homes. Accordingly, for future studies, it would be advisable to obtain a sample representative of the persons in the housing services to observe whether significant differences arise. Third, the fact that a large part of the sample attended day services and occupational therapy means they probably practiced PA within those hours and, in most cases, through programs set up by the organizations themselves. Future research should feature a larger presence of participants engaging in PA outside the service hours and using community resources. Likewise, it should be noted that studies on these topics ought to be undertaken; however, the limitations involved in the use of psychometric measurements should be improved. More specifically, measurements regarding PA should, at least, be complemented by behavioral, systematic, rigorous registers of the participants’ actual activity and frequency. Moreover, we must note the low participation of persons with severe and profound limitations due to their limited understanding and communication. It is true that the application of the instruments through an interview facilitated the participation of persons with highly limited understanding; however, the representation of this profile was smaller.

Finally, in summary, the eight domain QoL model allowed us to examine in detail the effect of PA practice on the personal, QoL-related outcomes. The values obtained allowed us to corroborate that, apart from the person's improved physical qualities, benefits are obtained in each domain. More specifically, the high results of the self-determination and the slightly lower values of social inclusion contributed previously unreported data. This study justifies the promotion of PA in everyday life for people with ID. In addition, the previous studies on the view of predicting components and mediating variables in the sphere of intellectual disability (Farmer, 2012; Schalock et al., in press) served as a framework to evaluate the way the variables described function.