Background/Objective Brief transdiagnostic psychotherapies are a possible treatment for emotional disorders. We aimed to determine their efficacy on mild/moderate emotional disorders compared with treatment as usual (TAU) based on pharmacological interventions. Method: This study was a single-blinded randomized controlled trial with parallel design of three groups. Patients (N = 102) were assigned to brief individual psychotherapy (n = 34), brief group psychotherapy (n = 34) or TAU (n = 34). Participants were assessed before and after the interventions with the following measures: PHQ-15, PHQ-9, PHQ-PD, GAD-7, STAI, BDI-II, BSI-18, and SCID. We conducted per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. Results: Brief psychotherapies were more effective than TAU for the reduction of emotional disorders symptoms and diagnoses with moderate/high effect sizes. TAU was only effective in reducing depressive symptoms. Conclusions: Brief transdiagnostic psychotherapies might be the treatment of choice for mild/moderate emotional disorders and they seem suitable to be implemented within health care systems.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: Las psicoterapias breves son un posible tratamiento para los trastornos emocionales. Nuestro propósito fue determinar su eficacia en los trastornos emocionales leves/moderados en comparación con el tratamiento habitual basado en intervenciones farmacológicas. Método: Este estudio fue un ensayo clínico aleatorizado simple ciego con diseño paralelo de tres grupos. Los pacientes (N = 102) fueron asignados a psicoterapia breve individual (n = 34), psicoterapia breve grupal (n = 34) o tratamiento habitual (n = 34). Los participantes fueron evaluados antes y después del tratamiento con los siguientes instrumentos: PHQ-15, PHQ-9, PHQ-PD, GAD-7, STAI, BDI-II, BSI-18 y SCID. Se realizaron análisis por protocolo y por intención de tratar. Resultados: Las psicoterapias breves fueron más efectivas que el tratamiento habitual para la reducción de síntomas y diagnósticos de los trastornos emocionales. El tratamiento habitual solo fue efectivo en reducir los síntomas depresivos. Conclusiones: Las psicoterapias breves pueden ser el tratamiento de elección para los trastornos emocionales leves/moderados y podrían implementarse en los sistemas de salud.

Emotional disorders (EDs) include diagnoses of depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE, 2011). They are the most prevalent mental disorders worldwide (World Health Organization WHO, 2017) and public health systems have pointed a concerning increase of them in the last decades (Chisholm et al., 2016). Scientific research indicates psychological therapies as the treatment of choice for EDs (Hollon et al., 2006; Joesch et al., 2011; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE, 2011; Watts et al., 2015). Although medication is recommended for severe cases, its use in patients with mild/moderate symptoms is usually unnecessary (Dunlop et al., 2019). In fact, it has been proven that psychotherapies promote higher rates of recovery for that patient profile (Wells et al., 2000). Individual and group psychological treatments have been two typical approaches to treat EDs, although there is not a clear consensus about whether there is a difference regarding their efficacy. In this sense, some studies claim the superiority of the individual approach (Gili et al., 2014; Hauksson et al., 2017; Moreno et al., 2013) while others conclude their equal efficacy (Cuijpers et al., 2008; Fawcett et al., 2019; Huntley et al., 2012; Neufeld et al., 2020; van Rijn & Wild, 2016). However, most of the patients are treated in primary care (PC) exclusively with medication, which might be a risk for their health (Bebbington et al., 2000). Moreover, even when patients are referred to specialized care, the adherence to psychological manualized treatments tends to be poor and incomplete (Gyani et al., 2015; Labrador et al., 2011).

For that reasons, “brief psychotherapies” emerged as a possible treatment for EDs, especially for those with mild/moderate symptoms (Shepardson et al., 2016). Following the meta-analysis of Cape et al. (2010), these therapies should have more than two and less than ten sessions and they have proven to be effective in reducing EDs symptoms (Bernhardsdottir et al., 2013; Koutra et al., 2010; Saravanan et al., 2017). Some works have shown that brief therapies obtain similar results to conventional therapies (Miller, 2000; Nieuwsma et al., 2012). Furthermore, brief psychotherapies appear to enhance the treatment adherence because of the use of time as a tool to develop therapeutic alliance (Bedics et al., 2005; Fosha, 2004). Due to the high comorbidity among EDs (González-Robles, Díaz-García, Miguel, García-Palacios, & Botella, 2018), transdiagnostic approaches have been developed to treat them simultaneously (Barlow et al., 2017; Sakiris & Berle, 2019). In fact, it has been pointed that most affective disorders share several underlying characteristics (McManus et al., 2011; Pascual-Vera et al., 2019). In this sense, one of the most important transdiagnostic treatment manuals is the Unified Protocol for the EDs (Barlow et al., 2014). It has been applied successfully in both individual (Barlow et al., 2017) and group formats (Bullis et al., 2015; Osma et al., 2018). Several studies have shown its effectiveness for the reduction of anxiety and depressive symptoms for patients with comorbid disorders (McManus et al, 2011; Norton, 2008; Sakiris & Berle, 2019). Furthermore, the recent review of Cassiello-Robins et al. (2020), suggests that the Unified Protocol can be applied in an abbreviated adaptation.

Due to the importance of implementing evidence-based interventions (Gálvez-Lara et al., 2018; Galvez-Lara, Corpas, Velasco et al., 2019; Moriana et al., 2017), more research about brief transdiagnostic therapies is needed. In this regard, the aim of this study is to determine the differential effects on EDs of brief individual and brief group psychotherapies compared with psychopharmacology interventions. It was hypothesized that patients receiving both types of brief psychotherapies would obtain greater clinical outcomes than patients being treated with psychotropic drugs. On the one hand, they would reduce more their EDs symptoms and, on the other hand, they would also remove more their diagnostic status for the different disorders. Furthermore, it was expected that patients receiving brief individual psychotherapy would obtain better clinical results (regarding both the severity of the symptoms and the loss of the diagnoses) than those receiving brief group psychotherapy.

MethodParticipantsThis was a randomized controlled trial conducted in PC and specialized care centers of Cordoba (Spain). Patients were recruited between November 2018 and November 2019 via their general practitioner when they consulted for the first time in PC with mild/moderate EDs symptoms. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 18-65 with at least one of the following EDs: depression disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and somatoform disorder. Predetermined cutoff points of different self-reported measures must be met: Generalized Anxiery Disorder Scale GAD-7 ≥ 5; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 PHQ-9 ≥ 10; Patient Health Questionnaire-15 PHQ-15 ≥ 5; Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder PHQ-PD ≥ 8 (Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Medrano et al., 2017; Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Moriana et al., 2017). Afterwards, a clinical assessment was developed using DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association APA, 2013) criteria according to SCID interview for anxiety, somatization and depression disorders in order to diagnose one or more EDs. Exclusion criteria included the presence severe mental disorders, severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 20), severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 15), recent suicide attempts, substance use disorders and intellectual disability. Participants that were already taking drugs that interfere with the Central Nervous System were also excluded. Patients were assigned randomly to one of the three following intervention according to a computer-generated allocation sequence (ratio 1:1:1):

- 1

Brief individual psychotherapy. Experimental group where patients received time-limited psychotherapy in an individual format. Treatment consisted in one session per week during eight weeks delivered by clinical psychologists in the Psychotherapy Unit of the Reina Sofia University Hospital of Cordoba (Spain). This intervention was designed according to an adaptation of the Unified Protocol for the transdiagnostic approach of EDs (Barlow et al., 2014; Ellard et al., 2010) and the NICE guideline "Common mental health disorders" (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE, 2011).

- S1

Motivation for change. Decisional balance techniques are used to defining therapeutic goals and increase commitment to treatment.

- S2

Emotional psychoeducation. Adaptive function of emotions and the concept of “emotion driven behaviors” are introduced.

- S3

Training in emotional awareness. Emotional awareness centered in the present without judging is taught and practiced.

- S4

Cognitive restructuring. Different techniques are used to detect and modify irrational ways of thinking.

- S5

Correct avoidant behaviors. The role of avoidant behaviors for the development and maintenance of EDs are explained in order to change them.

- S6

Increase tolerance to physical sensations. Several exercises that cause physical sensations are performed and discussed.

- S7

Emotional exposure. Emotional habituation is developed by encouraging patients to face symptom’s triggers.

- S8

Relapse prevention. Learned skills are reviewed and instructions to face future situations are offered.

- 2

Brief group psychotherapy. Experimental group where patients received the same intervention described above, but in a group format with approximately 10 participants. It was delivered by clinical psychologists in PC centers of Cordoba (Spain).

- 3

Treatment as Usual (TAU). Active comparator group where patients received pharmacological treatment (mainly anxiolytics and antidepressants) delivered by their general practitioner in the PC centers involved in the study. The consultations consisted in 5-7 minutes during a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 8 months (according to the general practitioner criteria) in which EDs symptoms were evaluated and drugs were prescribed.

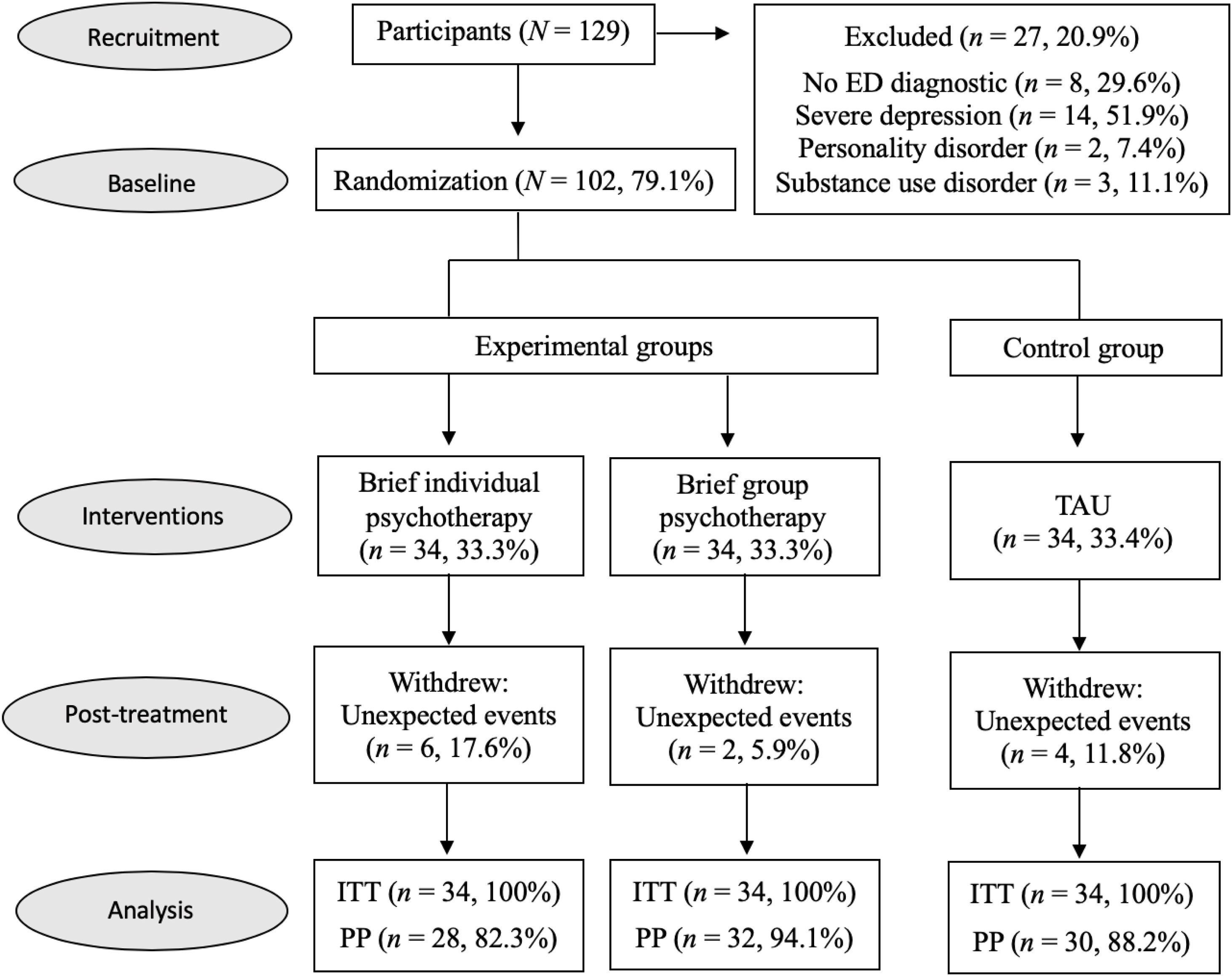

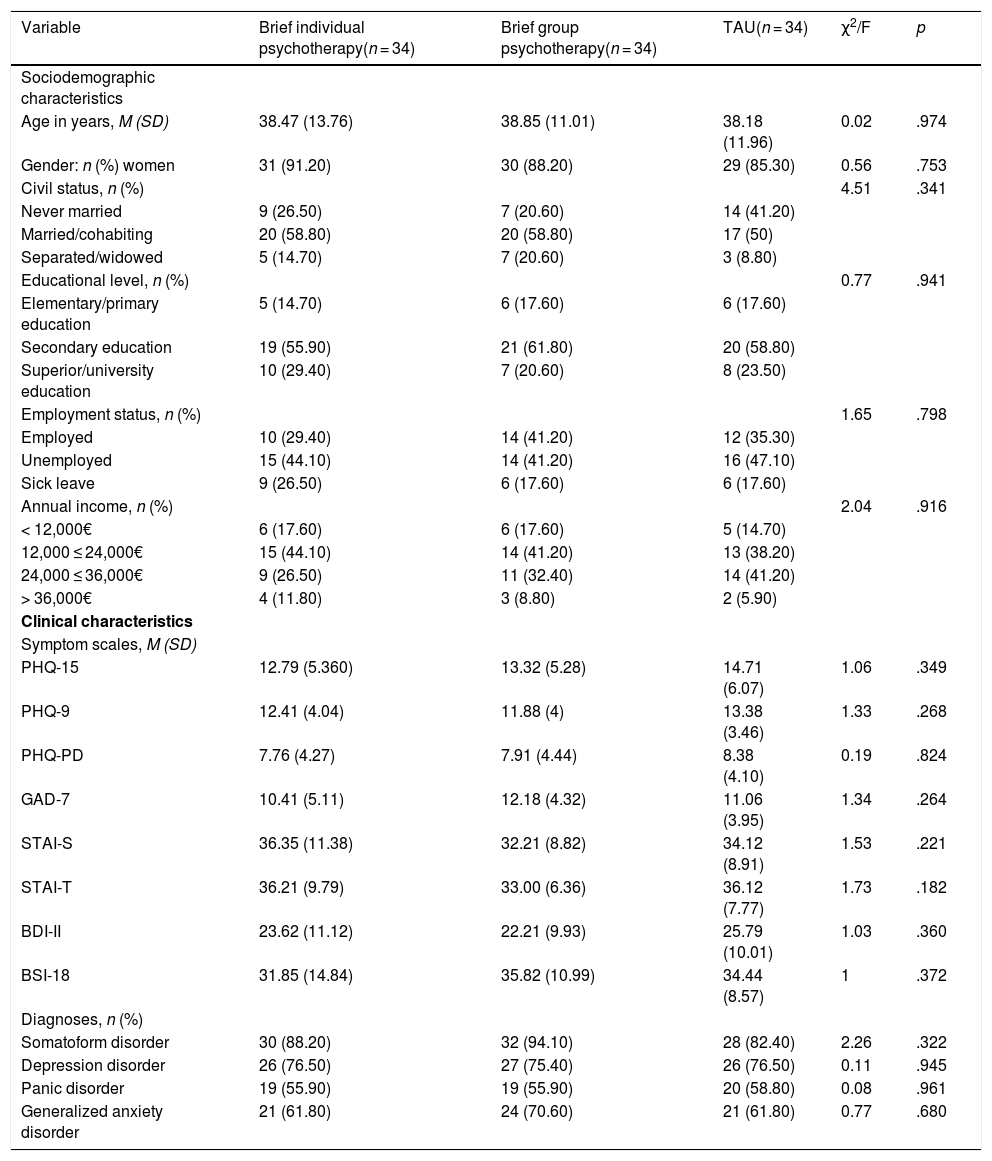

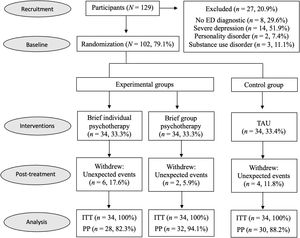

From the 129 participants recluted, 102 (79.10%) met inclusion criteria. Following the study design, they were randomized to brief individudal psychotherapy (n = 34), brief group psychotherapy (n = 34) and TAU (n = 34). Twelve (11.80%) patients abandoned their correspondent intervention. No demographic or clinical variables were related to this experimental mortality. Reasons participants gave for leaving the treatments were related to unexpected events in their lives such as city changes and family structural modifications. Flow diagram can be observed in Fig. 1. The most common patient profile was a married woman in her late thirties (M = 38.50, SD = 12.20), unemployed, earning less than €24.000 annually and presenting multiple EDs. No clinical or sociodemographic differences between the groups were observed (see Table 1).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the different groups at baseline (N = 102).

| Variable | Brief individual psychotherapy(n = 34) | Brief group psychotherapy(n = 34) | TAU(n = 34) | χ2/F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Age in years, M (SD) | 38.47 (13.76) | 38.85 (11.01) | 38.18 (11.96) | 0.02 | .974 |

| Gender: n (%) women | 31 (91.20) | 30 (88.20) | 29 (85.30) | 0.56 | .753 |

| Civil status, n (%) | 4.51 | .341 | |||

| Never married | 9 (26.50) | 7 (20.60) | 14 (41.20) | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 20 (58.80) | 20 (58.80) | 17 (50) | ||

| Separated/widowed | 5 (14.70) | 7 (20.60) | 3 (8.80) | ||

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.77 | .941 | |||

| Elementary/primary education | 5 (14.70) | 6 (17.60) | 6 (17.60) | ||

| Secondary education | 19 (55.90) | 21 (61.80) | 20 (58.80) | ||

| Superior/university education | 10 (29.40) | 7 (20.60) | 8 (23.50) | ||

| Employment status, n (%) | 1.65 | .798 | |||

| Employed | 10 (29.40) | 14 (41.20) | 12 (35.30) | ||

| Unemployed | 15 (44.10) | 14 (41.20) | 16 (47.10) | ||

| Sick leave | 9 (26.50) | 6 (17.60) | 6 (17.60) | ||

| Annual income, n (%) | 2.04 | .916 | |||

| < 12,000€ | 6 (17.60) | 6 (17.60) | 5 (14.70) | ||

| 12,000 ≤ 24,000€ | 15 (44.10) | 14 (41.20) | 13 (38.20) | ||

| 24,000 ≤ 36,000€ | 9 (26.50) | 11 (32.40) | 14 (41.20) | ||

| > 36,000€ | 4 (11.80) | 3 (8.80) | 2 (5.90) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Symptom scales, M (SD) | |||||

| PHQ-15 | 12.79 (5.360) | 13.32 (5.28) | 14.71 (6.07) | 1.06 | .349 |

| PHQ-9 | 12.41 (4.04) | 11.88 (4) | 13.38 (3.46) | 1.33 | .268 |

| PHQ-PD | 7.76 (4.27) | 7.91 (4.44) | 8.38 (4.10) | 0.19 | .824 |

| GAD-7 | 10.41 (5.11) | 12.18 (4.32) | 11.06 (3.95) | 1.34 | .264 |

| STAI-S | 36.35 (11.38) | 32.21 (8.82) | 34.12 (8.91) | 1.53 | .221 |

| STAI-T | 36.21 (9.79) | 33.00 (6.36) | 36.12 (7.77) | 1.73 | .182 |

| BDI-II | 23.62 (11.12) | 22.21 (9.93) | 25.79 (10.01) | 1.03 | .360 |

| BSI-18 | 31.85 (14.84) | 35.82 (10.99) | 34.44 (8.57) | 1 | .372 |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | |||||

| Somatoform disorder | 30 (88.20) | 32 (94.10) | 28 (82.40) | 2.26 | .322 |

| Depression disorder | 26 (76.50) | 27 (75.40) | 26 (76.50) | 0.11 | .945 |

| Panic disorder | 19 (55.90) | 19 (55.90) | 20 (58.80) | 0.08 | .961 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 21 (61.80) | 24 (70.60) | 21 (61.80) | 0.77 | .680 |

Notes. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; PHQ-PD = Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder; STAI-S/T = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State/Trait; TAU = Treatment as Usual.

Generalized Anxiery Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006). It measures anxiety symptoms between 0-21 points. Higher scores indicate higher severity. It has 7 items and patients rate the frequency of their anxiety symptoms in a 4-point Likert scale during the past 15 days. The scale has good internal consistency (α = .93) (García-Campayo et al., 2010).

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1983). It is a measure of state and trait anxiety. It has 40 items (20 for trait and 20 for state) with a 4-point Likert scale. We used and reported the two anxiety subscales (state and trait) independently. Scores vary between 0-60 points and higher scores indicate higher anxiety. It has good internal consistency (α = .86) (Spielberger et al., 1983).

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001). It is a screening tool for mayor depressive disorder. It has 9 items and patients rate their depresive symptoms using a 4-point Likert scale during the last 15 days. Scores vary between 0-27 and higher scores indicate higher severity. It has good internal consistency (α = .86 to .89) (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996). It measures the severity of depressive symptoms. It has 21 items with a 3-point Likert scale. Scores vary from 0-63 points and higher scores indicate worse mood. It has excellent internal consistency (α = .94) (Arnau et al., 2001).

Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15; Kroenke et al., 2002). It asseses somatoform disorder. Patients are asked to rate the frequency of their somatic symptoms through 15 items with a 3-points Likert scale. Scores vary from 0-30 points and higher scores indicate higher severity. It has good internal consistency (α = .78) (Montalban et al., 2010).

Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder (PHQ-PD; Spitzer et al., 1999). It is an assesement instrument for panic disorder. It has 15 items and patients respond affirmatively or negatively to the different symptoms. Scores vary from 0-15 points and higher scores indicate higher severity.

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2000). It asseses the severity EDs symptoms (anxiety, somatizations and depression). It has 18 items with a 4-point Likert scale. Scores vary between 0-72 points and higher scores indicate higher distress. It has excellent internal consistency (α = .93) (Franke et al., 2017).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID; First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015). It is a widely used clinical interview to diagnose mental disorders according to DSM-5 criteria. We focused on the studied disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, somatoform disorder and mayor depressive disorder.

ProcedureThis randomized controlled trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier NCT03286881 and its protocol was previously published (Gálvez-Lara, Corpas, Venceslá et al., 2019). Four experimental groups were originally planned, but due to the functioning of the public health system clinicians were not able to treat patients as indicated in two of them (combined treatment and minimum psychological intervention). Another of the experimental groups was changed from conventional psychotherapy to brief group psychotherapy to be able to evaluate one psychological intervention in PC.

Post-treatment assessments were developed between January 2019 and January 2020. They were in charge of a single independent clinical researcher. Follow-up assessments were planned to be performed between June 2019 and June 2020, but they were interrupted in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time the number of patients with follow-up data was less than the 30% for each group and, therefore, it was considered insufficient to be reported.

In order to guarantee the adherence to the psychological treatments, patients had to attend, at least, to seven of the eight sessions to be finally included in the study. The adherence to the medication was monitored by the general practitioners. For their part, the clinicians involved in the psychological treatments were previously trained in the abbreviated version of the Unified Protocol and they were systematically supervised to ensure they deliver the same intervention.

The sample size calculation process was described elsewhere (Gálvez-Lara, Corpas, Venceslá et al., 2019). In short, we assumed an effect size of 0.60 (Cohen´s d), which is equivalent to an f index of 0.30. Using G*Power program, with a statistical power of 0.80 and α = .05, we determited the need of 28 subjects per group. Since we assumed an abandonment rate of 15%, 33 participant in each group were finally requiered.

The study was authorized by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the Ministry of Health of the Andalusian Government (Spain) (code: PSI-2014-56368-R). Participants provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study. Data was treated according to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDRP) of the European Union. Participants received all relevant information about the study, including the possibility of ending their engagement at any time. The interventions did not suppose any danger for the patients except the one related with psychotropic drugs that could have effect sides. A single-blinded process was applied where only the researcher involved in the post-treatment assessments was blinded to the intervention condition. For their part, clinicians and patients knew their treatment allocation.

Statistical analysesData was analyzed following both intention-to-treat (all patients randomized are included in the analyses) and per protocol (only patients with post-treatment assesment are included in the analyses) approaches. Missing data in the intention-to-treat sample was completed using the maximum likelihood estimation method. Firstly, ANOVA or chi-squared analyses were performed to compare the sociodemographic and baseline clinical variables of the different groups. Secondly, linear mixed models were performed to determine intra and inter-group longitudinal changes in EDs symptoms. We used linear mixed models instead of ANOVAs because of their accuracy in handling missing data and incorporate random effects (Gueorguieva & Krystal, 2004). Specific comparisions by pairs of groups were also performed with the same statistical test. The effect sizes were calculated by Cohen´s d (bias corrected) (Hedges, 1981) as a measure of the differences between standardized mean changes (pre-post) of the respective groups (Becker, 1988). According to Cohen (1988), d values close to 0.20, 0.50 and 0.80 indicate low, moderate and high effect, respectively. The 95% confidence intervals for every effect size were also calculated. Lastly, chi-squared tests were performed to determine intra and inter-group longitudinal changes in patients meeting criteria for each disorder, as well as the specific group comparisons. The effect sizes were calculated by Cramér’s V statistical (Cramér, 1946) in order to delucidate the differences between the diagnoses percentage changes of the respective groups. According to Cohen (1988), V values close to 0.10, 0.30 and 0.50 indicate small, medium and large effect, respectively.

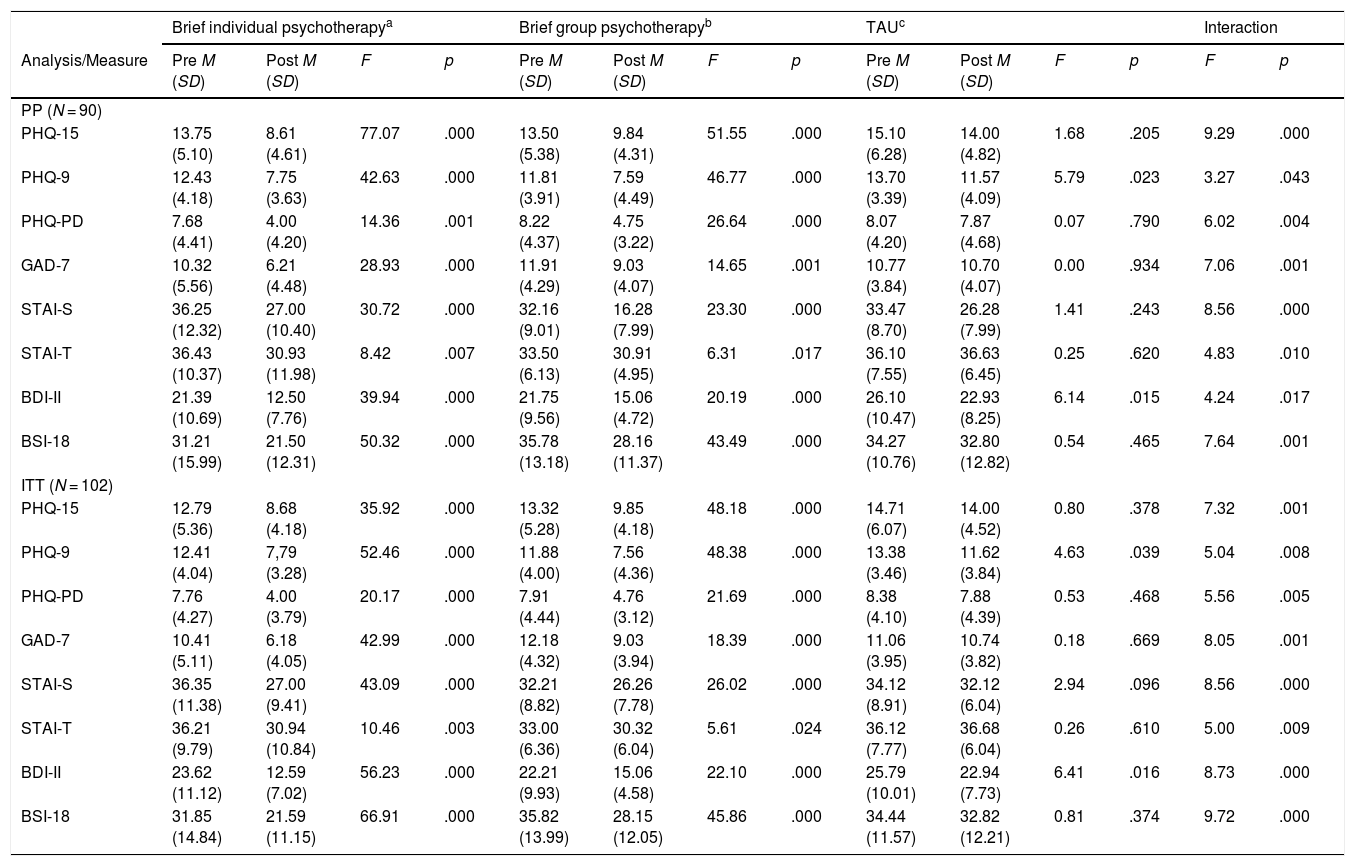

ResultsEffect on EDs symptomsBrief individual psychotherapy showed a significant reduction for all EDs symptoms in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. Brief group psychotherapy also showed a significant reduction for all EDs symptoms in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. TAU only showed a significant reduction for depressive symptoms in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. We found significant differences in the reduction of all EDs symptoms when comparing the three groups in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. Further information can be found on Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of the different groups and measures of EDs symptoms at baseline and post-treatment and linear mixed model intra and inter-group analyses for both per protocol and intention-to-treat samples.

| Brief individual psychotherapya | Brief group psychotherapyb | TAUc | Interaction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis/Measure | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | F | p | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | F | p | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | F | p | F | p |

| PP (N = 90) | ||||||||||||||

| PHQ-15 | 13.75 (5.10) | 8.61 (4.61) | 77.07 | .000 | 13.50 (5.38) | 9.84 (4.31) | 51.55 | .000 | 15.10 (6.28) | 14.00 (4.82) | 1.68 | .205 | 9.29 | .000 |

| PHQ-9 | 12.43 (4.18) | 7.75 (3.63) | 42.63 | .000 | 11.81 (3.91) | 7.59 (4.49) | 46.77 | .000 | 13.70 (3.39) | 11.57 (4.09) | 5.79 | .023 | 3.27 | .043 |

| PHQ-PD | 7.68 (4.41) | 4.00 (4.20) | 14.36 | .001 | 8.22 (4.37) | 4.75 (3.22) | 26.64 | .000 | 8.07 (4.20) | 7.87 (4.68) | 0.07 | .790 | 6.02 | .004 |

| GAD-7 | 10.32 (5.56) | 6.21 (4.48) | 28.93 | .000 | 11.91 (4.29) | 9.03 (4.07) | 14.65 | .001 | 10.77 (3.84) | 10.70 (4.07) | 0.00 | .934 | 7.06 | .001 |

| STAI-S | 36.25 (12.32) | 27.00 (10.40) | 30.72 | .000 | 32.16 (9.01) | 16.28 (7.99) | 23.30 | .000 | 33.47 (8.70) | 26.28 (7.99) | 1.41 | .243 | 8.56 | .000 |

| STAI-T | 36.43 (10.37) | 30.93 (11.98) | 8.42 | .007 | 33.50 (6.13) | 30.91 (4.95) | 6.31 | .017 | 36.10 (7.55) | 36.63 (6.45) | 0.25 | .620 | 4.83 | .010 |

| BDI-II | 21.39 (10.69) | 12.50 (7.76) | 39.94 | .000 | 21.75 (9.56) | 15.06 (4.72) | 20.19 | .000 | 26.10 (10.47) | 22.93 (8.25) | 6.14 | .015 | 4.24 | .017 |

| BSI-18 | 31.21 (15.99) | 21.50 (12.31) | 50.32 | .000 | 35.78 (13.18) | 28.16 (11.37) | 43.49 | .000 | 34.27 (10.76) | 32.80 (12.82) | 0.54 | .465 | 7.64 | .001 |

| ITT (N = 102) | ||||||||||||||

| PHQ-15 | 12.79 (5.36) | 8.68 (4.18) | 35.92 | .000 | 13.32 (5.28) | 9.85 (4.18) | 48.18 | .000 | 14.71 (6.07) | 14.00 (4.52) | 0.80 | .378 | 7.32 | .001 |

| PHQ-9 | 12.41 (4.04) | 7,79 (3.28) | 52.46 | .000 | 11.88 (4.00) | 7.56 (4.36) | 48.38 | .000 | 13.38 (3.46) | 11.62 (3.84) | 4.63 | .039 | 5.04 | .008 |

| PHQ-PD | 7.76 (4.27) | 4.00 (3.79) | 20.17 | .000 | 7.91 (4.44) | 4.76 (3.12) | 21.69 | .000 | 8.38 (4.10) | 7.88 (4.39) | 0.53 | .468 | 5.56 | .005 |

| GAD-7 | 10.41 (5.11) | 6.18 (4.05) | 42.99 | .000 | 12.18 (4.32) | 9.03 (3.94) | 18.39 | .000 | 11.06 (3.95) | 10.74 (3.82) | 0.18 | .669 | 8.05 | .001 |

| STAI-S | 36.35 (11.38) | 27.00 (9.41) | 43.09 | .000 | 32.21 (8.82) | 26.26 (7.78) | 26.02 | .000 | 34.12 (8.91) | 32.12 (6.04) | 2.94 | .096 | 8.56 | .000 |

| STAI-T | 36.21 (9.79) | 30.94 (10.84) | 10.46 | .003 | 33.00 (6.36) | 30.32 (6.04) | 5.61 | .024 | 36.12 (7.77) | 36.68 (6.04) | 0.26 | .610 | 5.00 | .009 |

| BDI-II | 23.62 (11.12) | 12.59 (7.02) | 56.23 | .000 | 22.21 (9.93) | 15.06 (4.58) | 22.10 | .000 | 25.79 (10.01) | 22.94 (7.73) | 6.41 | .016 | 8.73 | .000 |

| BSI-18 | 31.85 (14.84) | 21.59 (11.15) | 66.91 | .000 | 35.82 (13.99) | 28.15 (12.05) | 45.86 | .000 | 34.44 (11.57) | 32.82 (12.21) | 0.81 | .374 | 9.72 | .000 |

Notes. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; ITT = Intention-to-Treat; PHQ-PD = Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorders; PP = Per Protocol; STAI-S/T = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State/Trait; TAU = Treatment as Usual an = 28 for PP / 34 for ITT; bn = 32 for PP / 34 for ITT; cn = 30 for PP / 34 for ITT.

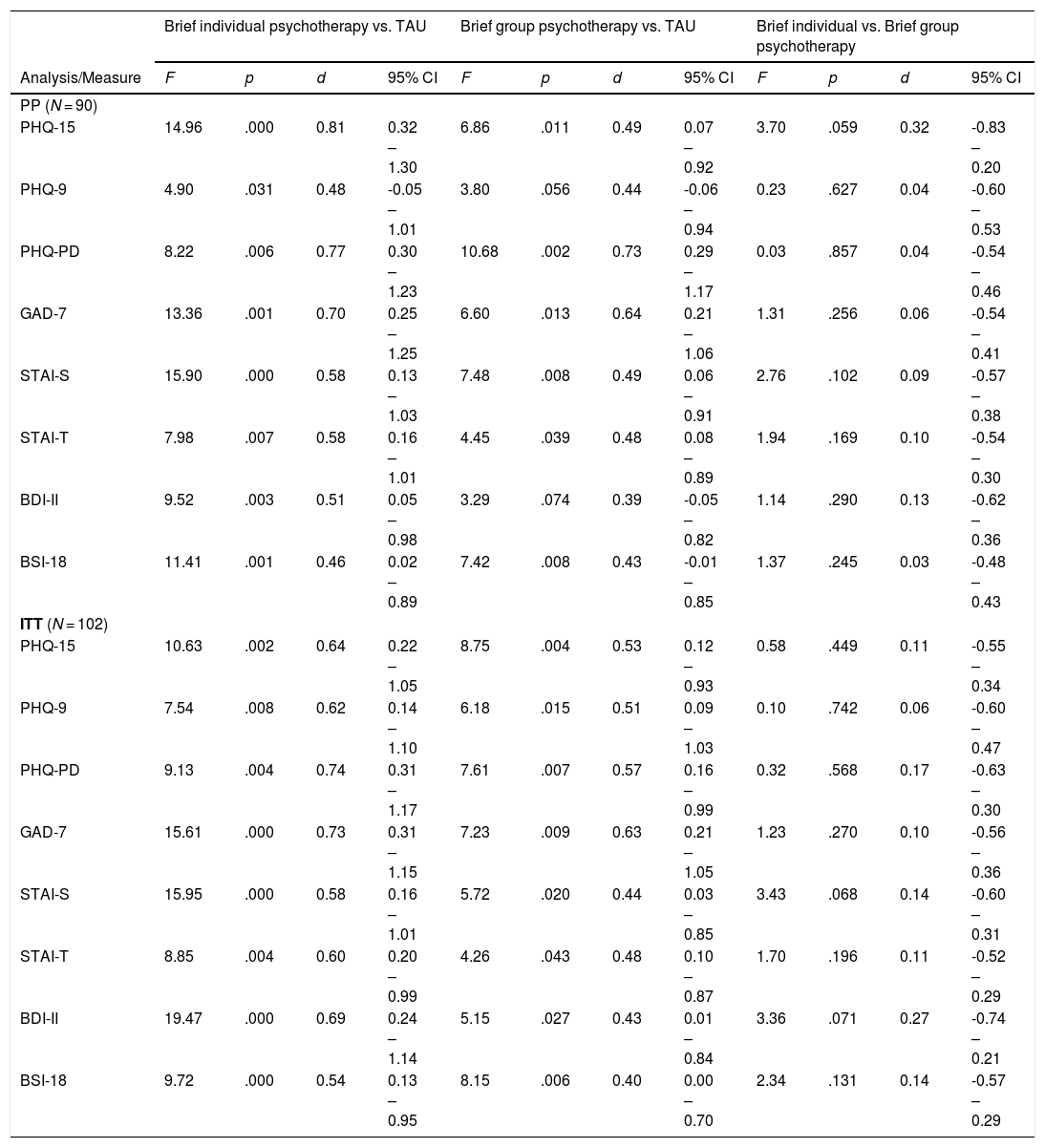

When comparing brief individual psychotherapy and TAU we obtained significant differences for all EDs symptoms with high/moderate effect sizes favorable to brief individual psychotherapy in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. When comparing brief group psychotherapy with TAU we obtained significant differences for all EDs symptoms except for depressive ones in per protocol analyses and for all EDs symptoms in intention-to-treat analyses. The effect sizes were moderate favorable to brief group psychotherapy. When comparing brief individual with brief group psychotherapies no significant differences were obtained for any EDs symptoms neither in per protocol nor in intention-to-treat analyses. The effect sizes for this comparison were low (see Table 3).

Multiple comparations analyses between groups of the pre-post differences in the measures of EDs symptoms and effect sizes for both per protocol and intention-to-treat samples.

| Brief individual psychotherapy vs. TAU | Brief group psychotherapy vs. TAU | Brief individual vs. Brief group psychotherapy | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis/Measure | F | p | d | 95% CI | F | p | d | 95% CI | F | p | d | 95% CI |

| PP (N = 90) | ||||||||||||

| PHQ-15 | 14.96 | .000 | 0.81 | 0.32 – 1.30 | 6.86 | .011 | 0.49 | 0.07 – 0.92 | 3.70 | .059 | 0.32 | -0.83 – 0.20 |

| PHQ-9 | 4.90 | .031 | 0.48 | -0.05 – 1.01 | 3.80 | .056 | 0.44 | -0.06 – 0.94 | 0.23 | .627 | 0.04 | -0.60 – 0.53 |

| PHQ-PD | 8.22 | .006 | 0.77 | 0.30 – 1.23 | 10.68 | .002 | 0.73 | 0.29 – 1.17 | 0.03 | .857 | 0.04 | -0.54 – 0.46 |

| GAD-7 | 13.36 | .001 | 0.70 | 0.25 – 1.25 | 6.60 | .013 | 0.64 | 0.21 – 1.06 | 1.31 | .256 | 0.06 | -0.54 – 0.41 |

| STAI-S | 15.90 | .000 | 0.58 | 0.13 – 1.03 | 7.48 | .008 | 0.49 | 0.06 – 0.91 | 2.76 | .102 | 0.09 | -0.57 – 0.38 |

| STAI-T | 7.98 | .007 | 0.58 | 0.16 – 1.01 | 4.45 | .039 | 0.48 | 0.08 – 0.89 | 1.94 | .169 | 0.10 | -0.54 – 0.30 |

| BDI-II | 9.52 | .003 | 0.51 | 0.05 – 0.98 | 3.29 | .074 | 0.39 | -0.05 – 0.82 | 1.14 | .290 | 0.13 | -0.62 – 0.36 |

| BSI-18 | 11.41 | .001 | 0.46 | 0.02 – 0.89 | 7.42 | .008 | 0.43 | -0.01 – 0.85 | 1.37 | .245 | 0.03 | -0.48 – 0.43 |

| ITT (N = 102) | ||||||||||||

| PHQ-15 | 10.63 | .002 | 0.64 | 0.22 – 1.05 | 8.75 | .004 | 0.53 | 0.12 – 0.93 | 0.58 | .449 | 0.11 | -0.55 – 0.34 |

| PHQ-9 | 7.54 | .008 | 0.62 | 0.14 – 1.10 | 6.18 | .015 | 0.51 | 0.09 – 1.03 | 0.10 | .742 | 0.06 | -0.60 – 0.47 |

| PHQ-PD | 9.13 | .004 | 0.74 | 0.31 – 1.17 | 7.61 | .007 | 0.57 | 0.16 – 0.99 | 0.32 | .568 | 0.17 | -0.63 – 0.30 |

| GAD-7 | 15.61 | .000 | 0.73 | 0.31 – 1.15 | 7.23 | .009 | 0.63 | 0.21 – 1.05 | 1.23 | .270 | 0.10 | -0.56 – 0.36 |

| STAI-S | 15.95 | .000 | 0.58 | 0.16 – 1.01 | 5.72 | .020 | 0.44 | 0.03 – 0.85 | 3.43 | .068 | 0.14 | -0.60 – 0.31 |

| STAI-T | 8.85 | .004 | 0.60 | 0.20 – 0.99 | 4.26 | .043 | 0.48 | 0.10 – 0.87 | 1.70 | .196 | 0.11 | -0.52 – 0.29 |

| BDI-II | 19.47 | .000 | 0.69 | 0.24 – 1.14 | 5.15 | .027 | 0.43 | 0.01 – 0.84 | 3.36 | .071 | 0.27 | -0.74 – 0.21 |

| BSI-18 | 9.72 | .000 | 0.54 | 0.13 – 0.95 | 8.15 | .006 | 0.40 | 0.00 – 0.70 | 2.34 | .131 | 0.14 | -0.57 – 0.29 |

Notes. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; ITT = Intention-to-Treat; PHQ-PD = Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder; PP = Per Protocol; STAI-S/T = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State/Trait; TAU = Treatment as Usual.

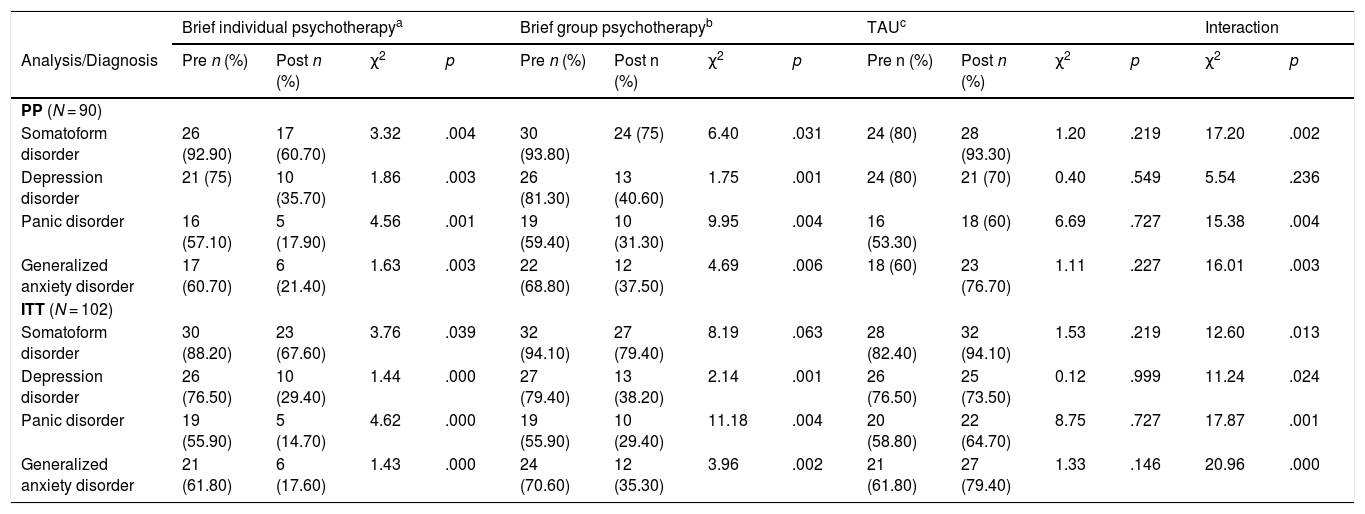

Brief individual psychotherapy showed a significant reduction for all the EDs diagnoses in both per protocol and intention-to-treat analyses. Brief group psychotherapy also showed a significant reduction for all EDs diagnoses in per protocol analyses and for all the diagnoses except for somatoform disorder in intention-to-treat analyses. TAU showed no significant increasement/reduction for any ED diagnosis neither in per protocol nor in intention-to-treat analyses. When comparing the three groups, we found significant differences in the reduction of all EDs diagnoses except for mayor depression in per protocol analyses and for all EDs diagnoses in intention-to-treat analyses. Further information can be found on see Table 4.

Frequency and percentage of patients meeting DSM-5 criteria for each disorder at baseline and post-treatment and chi-squared intra and inter-group analyses for both per protocol and intention-to-treat samples.

| Brief individual psychotherapya | Brief group psychotherapyb | TAUc | Interaction | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis/Diagnosis | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | χ2 | p | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | χ2 | p | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) | χ2 | p | χ2 | p |

| PP (N = 90) | ||||||||||||||

| Somatoform disorder | 26 (92.90) | 17 (60.70) | 3.32 | .004 | 30 (93.80) | 24 (75) | 6.40 | .031 | 24 (80) | 28 (93.30) | 1.20 | .219 | 17.20 | .002 |

| Depression disorder | 21 (75) | 10 (35.70) | 1.86 | .003 | 26 (81.30) | 13 (40.60) | 1.75 | .001 | 24 (80) | 21 (70) | 0.40 | .549 | 5.54 | .236 |

| Panic disorder | 16 (57.10) | 5 (17.90) | 4.56 | .001 | 19 (59.40) | 10 (31.30) | 9.95 | .004 | 16 (53.30) | 18 (60) | 6.69 | .727 | 15.38 | .004 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 17 (60.70) | 6 (21.40) | 1.63 | .003 | 22 (68.80) | 12 (37.50) | 4.69 | .006 | 18 (60) | 23 (76.70) | 1.11 | .227 | 16.01 | .003 |

| ITT (N = 102) | ||||||||||||||

| Somatoform disorder | 30 (88.20) | 23 (67.60) | 3.76 | .039 | 32 (94.10) | 27 (79.40) | 8.19 | .063 | 28 (82.40) | 32 (94.10) | 1.53 | .219 | 12.60 | .013 |

| Depression disorder | 26 (76.50) | 10 (29.40) | 1.44 | .000 | 27 (79.40) | 13 (38.20) | 2.14 | .001 | 26 (76.50) | 25 (73.50) | 0.12 | .999 | 11.24 | .024 |

| Panic disorder | 19 (55.90) | 5 (14.70) | 4.62 | .000 | 19 (55.90) | 10 (29.40) | 11.18 | .004 | 20 (58.80) | 22 (64.70) | 8.75 | .727 | 17.87 | .001 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 21 (61.80) | 6 (17.60) | 1.43 | .000 | 24 (70.60) | 12 (35.30) | 3.96 | .002 | 21 (61.80) | 27 (79.40) | 1.33 | .146 | 20.96 | .000 |

Notes. ITT = Intention-to-Treat; PP = Per Protocol; TAU = Treatment as Usual. an = 28 for PP / 34 for ITT; bn = 32 for PP / 34 for ITT; cn = 30 for PP / 34 for ITT.

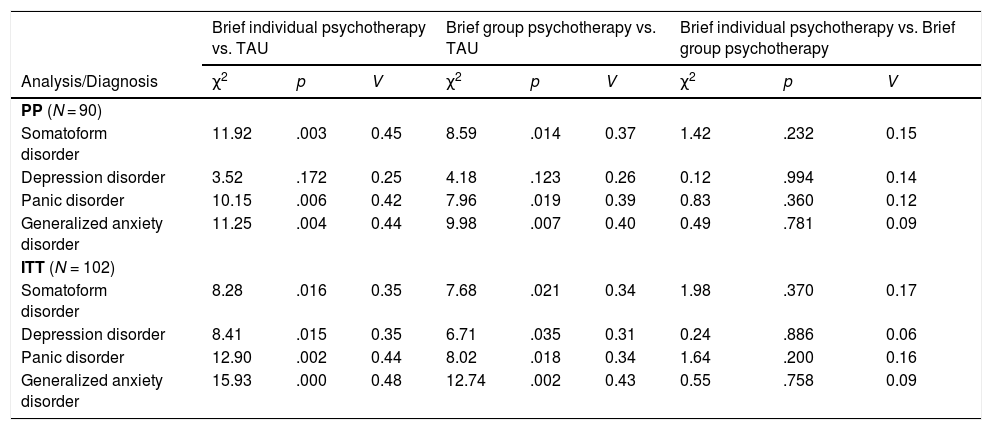

When comparing brief individual psychotherapy and TAU we obtained significant differences for every ED diagnosis, except for depression disorder in per protocol analyses and for every EDs diagnosis in intention-to-treat analyses. Large effect sizes favorable to brief individual psychotherapy were obtained. When comparing brief group psychotherapy with TAU we obtained significant differences for every ED diagnosis, expect for depression disorder in per protocol analyses and for every ED diagnosis in intention-to-treat analyses. Moderate effect sizes favorable to brief group psychotherapy were obtained. When comparing brief individual and brief group psychotherapies no significant differences were found for any ED diagnosis neither in per protocol nor in intention-to-treat analyses (see Table 5).

Multiple comparations analyses between groups of the pre-post differences in meeting DSM-5 criteria for the different diagnoses and effect sizes for both per protocol and intention-to-treat samples.

| Brief individual psychotherapy vs. TAU | Brief group psychotherapy vs. TAU | Brief individual psychotherapy vs. Brief group psychotherapy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis/Diagnosis | χ2 | p | V | χ2 | p | V | χ2 | p | V |

| PP (N = 90) | |||||||||

| Somatoform disorder | 11.92 | .003 | 0.45 | 8.59 | .014 | 0.37 | 1.42 | .232 | 0.15 |

| Depression disorder | 3.52 | .172 | 0.25 | 4.18 | .123 | 0.26 | 0.12 | .994 | 0.14 |

| Panic disorder | 10.15 | .006 | 0.42 | 7.96 | .019 | 0.39 | 0.83 | .360 | 0.12 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 11.25 | .004 | 0.44 | 9.98 | .007 | 0.40 | 0.49 | .781 | 0.09 |

| ITT (N = 102) | |||||||||

| Somatoform disorder | 8.28 | .016 | 0.35 | 7.68 | .021 | 0.34 | 1.98 | .370 | 0.17 |

| Depression disorder | 8.41 | .015 | 0.35 | 6.71 | .035 | 0.31 | 0.24 | .886 | 0.06 |

| Panic disorder | 12.90 | .002 | 0.44 | 8.02 | .018 | 0.34 | 1.64 | .200 | 0.16 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 15.93 | .000 | 0.48 | 12.74 | .002 | 0.43 | 0.55 | .758 | 0.09 |

Notes. ITT = Intention-to-Treat; PP = Per Protocol; TAU = Treatment as Usual.

According to our results, both individual and group psychotherapies were effective for the reduction of EDs symptoms. This outcome would be in the line of other studies that have pointed satisfactory clinical results of transdiagnostic and brief psychological treatments for anxiety and depression disorders (Cape et al., 2010; Sakiris & Berle, 2019; Saravanan et al., 2017). We found that the pharmacological intervention was only effective in reducing depressive symptoms, which is also consistent with previous research (Cuijpers et al., 2020). It has been noted that most patients are unsatisfied with an exclusively medication approach for their EDs (Prins et al., 2009). That might be the reason why they are prone to consult repeatedly in PC, which causes deterioration of health systems (Gili et al., 2011). Similarly, both brief psychotherapies were effective in removing the diagnoses of somatoform disorder, depression disorder, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Despite brief group psychotherapy was not statistically significant for the reduction of somatoform disorder in intention-to-treat analysis, a recent clinical guide suggests this treatment as the first therapeutic step (Agarwal et al., 2020). This outcome supports the utility of the transdiagnostic approach to treat different EDs at the same time (Barlow et al., 2014; Brown & Barlow, 2009; Rosellini et al., 2015). The pharmacological intervention was not effective in removing any of the diagnoses. It appears that when patients are treated with medication alone their diagnoses tend to persist. Therefore, it is likely that they respond more to a psychological issue than to a strictly medical affection (Gili et al., 2011).

Both brief individual and group psychotherapies were more effective than TAU for the reduction of EDs symptoms. Although no statistically significant differences were found between the effects of brief group psychotherapy and TAU for depressive symptoms in per protocol analysis, it might be explained by the sample size. In fact, this comparison showed a moderate effect size and statistically significant differences were indeed found afterwards in intention-to-treat analysis. This outcome would be consistent with several studies that have pointed the superiority of psychological therapies over pharmacological ones for the treatment of EDs (Hollon et al., 2006; Joesch et al., 2012; Watts et al., 2015). However, a recent meta-analysis of Cuijpers et al. (2020) points that there are no differences in the efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacological interventions for depression. This statement would be opposite to our results if it was not because the majority of the randomized controlled trials of that study included patients with severe depression. On the contrary, we only accepted patients with mild/moderate depressive symptoms. Regarding the removal of the diagnostic status, both brief psychotherapies were more effective than TAU in reducing all the EDs diagnoses. Although no statistically differences were found between the effects of any of the two brief psychotherapies and TAU for the diagnosis of depression in per protocol analyses, those effects were indeed statistically significant in intention-to-treat analysis with moderate effect sizes. In view of the results, we confirmed our first hypothesis since patients randomized to the experimental groups showed better clinical results than those randomized to TAU.

No differences were found between individual and group psychotherapies approaches for any of the EDs symptoms or diagnoses, which was unexpected but consistent with previous research (Fawcett et al., 2019; van Rijn & Wild, 2016). This result might be explained by our restrictive inclusion criteria (such as no other comorbid mental disorders). It would be plausible that the individual approach showed some superiority in more complicated circumstances (Hauksson et al., 2017). Although the individual approach showed higher effect sizes in the reduction of EDs symptoms and diagnoses, we rejected our second hypothesis since patients receiving brief individual psychotherapy did not obtain better beneficial outcomes than those receiving brief group psychotherapy. In this sense, some complications of group psychological therapies have been pointed like the reluctance to share personal information with other patients (Shechtman & Kiezel, 2016). However, group therapies have greater cost-benefits ratios since they are able to reach more patients in less time, which would reduce wait-lists and would help health systems fluency (Koutra et al., 2010; Morrison, 2001).

The first limitation of this study was related to the impossibility of implementing follow-up assessments. Despite there is recent evidence that suggests that the improvement remains after receiving brief psychotherapies (Brent et al., 2020), their long-term efficacy have been questioned (Ali et al., 2017). For that reason, our findings might be restricted to the effects right after the interventions. Secondly, our results would be difficult to generalize to other populations like children, the elderly or patients with other mental disorders or disabilities. The present work is also limited to mild/moderate EDs. Therefore, we should be cautious about our results in more severe cases, where more intense psychological treatments and medication should be considered (Cuijpers et al., 2020; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE, 2011). Lastly, we only applied a single-blinded method and, therefore, patients and clinicians knew the allocation of the randomization process, what might produce outcome biases.

ConclusionsThis study shows that brief psychological interventions are more effective than pharmacological ones for mid/moderate EDs. Since most of the initial consultations in PC are related to non-severe symptoms of anxiety and depression (Ansseau et al., 2004), their use would be recommended as the first therapeutic approach. Moreover, it proves how transdiagnostic interventions could be useful to treat a whole variety of disorders at a time. Finally, this work reinforces the effectiveness of the stepped care approach for the treatment of EDs within public health systems (Martín et al., 2017). In this sense, brief psychological therapies would be the optimal choice when symptoms are mild/moderate and more intense psychotherapies (with or without adding medication) would be applied when facing severe cases. Furthermore, clinicians may opt for brief group psychotherapies applied in PC when patients are willing to accept this approach and may choose brief individual psychotherapies applied in specialized care when more risks or difficulties are presented. In light of above, it is concluded that brief transdiagnostic psychological therapies seem to be suitable to be implemented in practical contexts. It is our hope that this work contributes to the development and dissemination of brief psychological therapies within health systems in order to offer patients the best treatment possible.

FundingThis work was supported by a Grant from the Government of Spain (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad) (Grant Number PSI2014-56368-R).