Background/Objective: Diseases of the cardiovascular system and depression are common, and they often coexist, significantly deteriorating the quality of life. Another factor influencing vital functions is impairment of cognitive functions occurring in patients with heart failure (HF). Deficits of different degrees of severity have been observed within a variety of cognitive domains. Cognitive deficits, which may impair daily functioning, hinder adaptation to the disease and worsen prognosis, are also observed in depression. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between the quality of life, the severity of depressive disorders and disorders of certain executive functions, and memory in patients with severe, stable heart failure. Method: The study group consisted of 50 patients with stable, severe heart failure and 50 appropriately selected patients with coronary heart disease, without heart failure. Results: The results of cognitive tests are significantly lower in the HF group than in the control group. In the HF group, a significantly lower quality of life, as well as a higher result in the BDI-II test, was observed. No influence of cognitive disorders on the reduction in the quality of life was demonstrated. The factor that significantly affects the quality of life is the intensification of depression symptoms. Conclusions: The factor that significantly affects the quality of life is the intensification of depression symptoms.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: Las enfermedades cardiovasculares y la depresión son comunes, y muchas veces coexistentes, empeorando la calidad de vida. Además, existen trastornos de funciones cognitivas omnipresentes en pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca. Se observan deficiencias de distinto nivel de severidad en varios dominios cognitivos. Asimismo, en la depresión existen problemas cognitivos que podrían perjudicar el funcionamiento cotidiano, obstaculizar la adaptación a la enfermedad y empeorar los pronósticos. El objetivo del trabajo fue evaluar la relación entre calidad de vida, intensificación de trastornos depresivos y trastornos de ciertos aspectos de las funciones ejecutivas y memoria en pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca grave y estable. Método: Los estudios se realizaron en un grupo de 50 pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca grave y estable y otro de 50 pacientes con enfermedad coronaria, pero sin insuficiencia cardiaca. Resultados: Los resultados de las pruebas cognitivas son notablemente peores en el grupo con insuficiencia cardiaca en comparación con el grupo de control. Se observó una calidad de vida considerablemente peor y puntuaciones significativamente más altas en el BDI-II. No se demostró que los trastornos cognitivos influyeran en el empeoramiento de la calidad de vida. Sin embargo, se observó que los síntomas de depresión influían en la calidad de vida. Conclusiones: El factor que afecta significativamente a la calidad de vida es la intensificación de los síntomas depresivos.

Together with the development of medicine and its diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities, life expectancy has been considerably extended. Nowadays, effective medical intervention enables patients to survive situations that once inevitably ended in death. One consequence of this success in medicine is, however, an increase in the proportion of people suffering from various chronic diseases that significantly affect their quality of life. Currently, prevalent lifestyle diseases, such as coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, diabetes and depression, considerably limit the functioning of humans and hinder their adaptation to the requirements related to the situation of the disease and everyday life (Arrebola-Moreno et al., 2014; Granados-Gámez, Roales-Nieto, Gil-Luciano, Moreno-San Pedro, & Márquez-Hernández, 2015). The diseases interfere with functioning on many levels: physical, social and emotional.

Cognitive impairment is prevalent in heart failure (HF), with ranges from 30-89%, depending on the type of measurements used and characteristics of the studied sample (Stetkiewicz-Lewandowicz & Borkowska, 2013). Cognitive deficits in patients with HF are often subtle and difficult to detect with standard screening instruments (Pressler, 2008). Studies using neuropsychological instruments indicate that deficits of varying severity are observed in several cognitive domains, including memory, attention, executive function and psychomotor speed. These deficits have been found to be independent of age, sex, comorbidities, alcohol consumption and education level (Pressler et al., 2010a). People with HF have a more than four-fold risk of cognitive deficits compared to people without HF, after other factors such as age, gender and comorbidities have been taken into account (Sauve, Lewis, Blankenbiller, Rickabaugh, & Pressler, 2009). Quite often, the decline does not cause any significant functional impairment, and thus it does not meet the criteria for diagnosing dementia. It is defined as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), but approx. 25% of patients may have moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment (CI) (Kim, Hwang, Shim, & Jeong, 2015).

The mechanisms that contribute to cognitive deficits in HF still remain unclear. Studies have provided evidence that the clinically detected impairments in patients with HF may be the outcome of structural or neurodegenerative changes which cannot be reversed, and/or functional neuronal dysfunctions which may progress to neuronal cell death or improve in response to treatment (Dardiotis et al., 2012). Cerebral and systemic haemodynamics seem to influence the development of CI in patients with HF. Cerebral blood flow (CBF), estimated with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), was reduced by about 30% in patients with severe HF (NYHA class III/IV) (Gruhn et al., 2001), and may suggest that cognitive performance in patients with HF is related to cerebral perfusion. Cerebral perfusion is mediated by a number of factors, including cardiac output and cerebrovascular reactivity (Dardiotis et al., 2012). Another aspect of the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment in HF is the development of cerebral abnormalities as a result of chronic hypoperfusion or stroke (Ampadu & Morley, 2015). MRI studies revealed (Woo et al., 2015) that HF patients have an increased frequency of focal brain abnormality, ranging from multiple cortical or subcortical infarcts to small vessel disease with white-matter lesions and lacunar infarcts, with cerebral embolism and hypoperfusion being the most plausible mechanisms.

Depression and heart disease are common, and they frequently coexist, often worsening both the quality of life and prognosis of the patient due to poorer adherence to treatment (Muller, Hess, & Hager, 2012). The relationship between depression and heart disease is multidimensional. Depression is associated with several physiological derangements that could contribute to adverse cardiac outcomes. Patients with depression have high sympathetic tone, hypercortisolemia, elevated catecholamine levels, abnormal platelet activation, increased inflammatory markers and endothelial dysfunction (Rumsfeld & Ho, 2005), which further increase the risk of coronary events. Additionally, subjectively experienced problems with concentration, memory, problem solving and thinking occur and are likely to impair daily functioning (Evans, Iverson, Yatham, & Lam, 2014; Iverson & Lam, 2013).

There is compelling evidence that depression is the best predictor of quality of life in patients with CHD, both in short- and long-term CHD. While the relationship between depression and coronary heart disease has been extensively researched over the years, it is the role of health-related quality of life in this relationship that has recently become of interest. Patients with CHD experience numerous symptoms, including fatigue, dyspnoea, stenocardia and oedema, and it is important to assess how the disease impacts the patient's physical, emotional and social well-being. It is known that a low quality of life decreases the patient's motivation to adhere to recommendations, which is conducive to depression and significantly worsens the prognosis (Ubiegło, Uchmanowicz, Wleklik, Jankowka-Polańska, & Kuśmierz, 2015).

The main objective of the study was to assess the relationship between the quality of life, severity of depressive disorders, and memory impairment, as well as some aspects of the executive functions in patients listed for elective heart transplant. The study was conducted in a very specific and rare group of patients. These were patients with extreme but stable heart failure and without any other severe comorbidities or multiple organ inefficiency, which often occurs in patients with heart failure. Another objective was to assess cognitive impairment patterns in this group of patients.

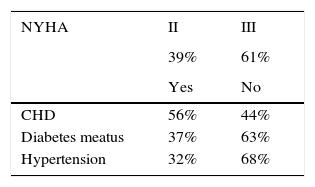

MethodParticipantsThe convenience cohort study consisted of 50 patients with severe heart failure (age range: 34-68 years) among patients listed for elective heart transplant (HTx), recruited from the Clinical Cardiology Centre, and 50 age-, gender- and level of education- matched volunteers (age range: 43-68 years) with stable coronary artery disease without HF, recruited from the Department of Rehabilitation and Department of Cardiology and Cardiac Rehabilitation of the University Clinical Centre in Gdańsk. The study group consisted of highly-selected patients who met the procedure HTx eligibility criteria, which means no multiple organ inefficiency or severe comorbidities such as poorly controlled/uncontrolled diabetes. All consecutive patients eligible for HTx procedures were included in the study. The clinical characteristics of patients with HF are presented in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with severe HF.

| NYHA | II | III |

|---|---|---|

| 39% | 61% | |

| Yes | No | |

| CHD | 56% | 44% |

| Diabetes meatus | 37% | 63% |

| Hypertension | 32% | 68% |

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF | 18 | 5 | 10 | 30 |

| creatinine | 1.12 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| VO2max | 9.8 | 2.7 | 6 | 15 |

| 6MWT | 296 | 91 | 150 | 503 |

Note. NYHA: New York Heart Association Functional Classification; CHD: coronary heart disease; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; VO2max: maximal oxygen uptake; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test.

The average age of the HF subjects (42 males and 8 females) was 56 years (SD=8), and the average age for the control group (44 males and 6 females) was also 56 years (SD=9). The differences in the mean ages and gender of the examined and control groups were found to be statistically insignificant. The study group included patients with heart failure (EF <20%) who achieved at least 24 points in the MMSE, were able to understand questions/tasks, and agreed to participate in the study. The following were excluded from participation in the study: people with a diagnosis of a major depressive disorder, history of an affective disorder or schizophrenia, disorders of cerebral circulation, craniocerebral trauma, renal insufficiency, alcoholism, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy, disorders of consciousness, and serious somatic disorders, especially during decompensation. The control group included patients without heart failure, with stable coronary artery disease found by angiography, and with no apparent abnormalities which are indicated for exclusion from the HF group.

ProcedureThe study was conducted from 01 January 2013 to 31 March 2015. The study protocol included medical history (Table 1), assessment of cognitive functions, quality of life (MacNew questionnaire) and screening for depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II, BDI-II). Each patient underwent a psychiatric examination. Patients diagnosed with mental disorders were excluded from subsequent studies. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdańsk approved the study protocols (NKEBN/180/2013). Upon entering the study, each participant gave his or her informed consent.

Measures- -

Assessment of HRQL. Group differences in perception of quality of life were determined by an analysis based on the MacNew health-related quality of life questionnaire (MacNew HRQL) (Lim et al., 1993). This was designed to assess cardiac patients’ feelings concerning how their daily functioning is affected by heart disease. The questionnaire contains 27 items with a global HRQL score, and physical, emotional and social subscales. The MacNew questionnaire has a 2-week timeframe to assess a patient's feelings about daily functioning, with each item scored from 1 (low HRQL) to 7 (high HRQL). In our study we used a Polish version of the MacNew questionnaire, validated in a cardiac cohort by Moryś, Höfer, Rynkiewicz, & Oldridge (2015).

- -

Neuropsychological assessment. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is effective as a screening tool for cognitive impairment, and it tests five areas of cognitive function: orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall and language (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). In our study, we used a Polish version drawn up by Stańczak (Folstein, Folstein, & Fanjiang, 2009). Verbal fluency was tested with the use of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, 1983). The task was to list, within 60seconds, as many words beginning with the letter “k”, and animals and objects beginning with the letter “m” that can be bought in a supermarket. The digit span test from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-R, PL) served to test attention span and reversing operation (mental double-tracking) (Brzeziński et al., 2004; Wechsler, 1981). The Color Trails Test (CTT) (D’Elia, Satz, Uchiyama, & White, 1996; Łojek & Stańczak, 2012) was used for the evaluation of attention, visual search and scanning, sequencing and shifting, psychomotor speed, and the ability to maintain two trains of thought simultaneously (executive functions). The spatial span from the Wechsler Memory Scale - III (WMS-III) was used as an indicator of working memory and visuospatial processing, while Logical Memory (LM) was used to assess short- and long-term organised verbal memory (Wechsler, 1997). The California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Ober, 1987; Łojek & Stańczak, 2010) served to measure verbal learning abilities and memory.

- -

Evaluation of depressive symptoms. BDI-II is the gold standard of self-rating scales, designed to measure the severity of symptoms of depression in patients experienced in the past two weeks (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). In screening, a total score of 14 or higher is the most widely used cut-off for clinically significant depression. The following guidelines have been suggested to interpret BDI-II: scores of 0 to 13 indicate no depression, 14 to 19 mild depression, 20 to 28 moderate depression and 29 to 63 indicate severe depression. In our study, we used a Polish version of the BDI drawn up by Parnowski and Jernajczyk (1977).

All results are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Distribution of continuous variables was assessed in terms of its compliance with normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Statistical significance of differences between the means of continuous variables with normal distribution were evaluated using Student's t test, and the average distributed variables different from the normal Mann-Whitney U test. To determine the correlation between the different parameters, the Spearman correlation index (r) was used. Values of p<.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using the commercial statistical package STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 10, by StatSoft, Inc. (2011) Tulsa, United States.

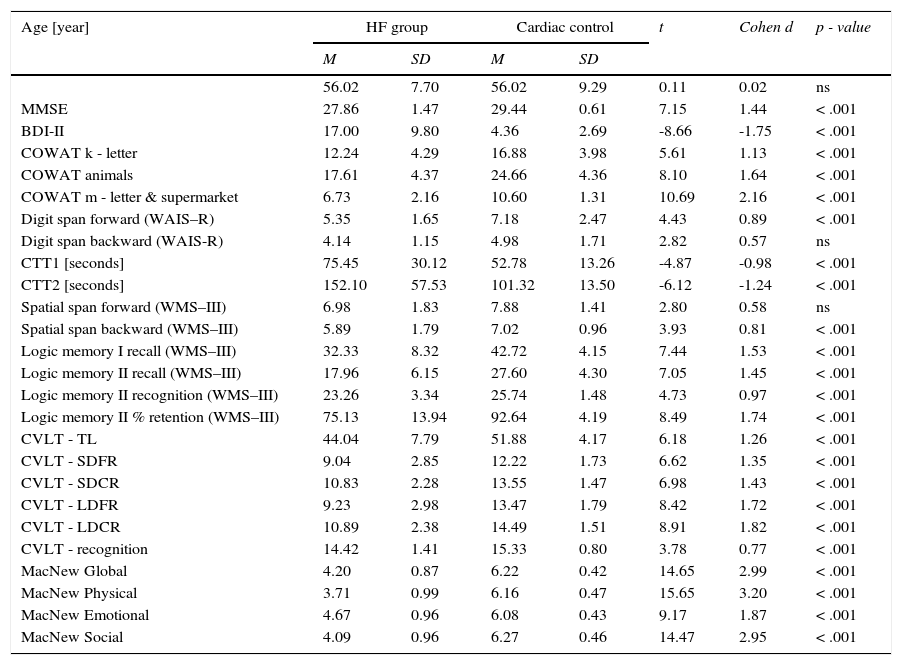

ResultsCognitive performance in the HF group was significantly lower than in the cardiac control group (Table 2). Poorer results were observed both during the general screening (MMSE) and in almost all the tests. Only in the case of digit span backward and spatial span forward was there no statistically significant difference between the HF and cardiac control groups.

Descriptive statistics of the cognitive performance and the symptoms of depression in the HF and cardiac control groups.

| Age [year] | HF group | Cardiac control | t | Cohen d | p - value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| 56.02 | 7.70 | 56.02 | 9.29 | 0.11 | 0.02 | ns | |

| MMSE | 27.86 | 1.47 | 29.44 | 0.61 | 7.15 | 1.44 | < .001 |

| BDI-II | 17.00 | 9.80 | 4.36 | 2.69 | -8.66 | -1.75 | < .001 |

| COWAT k - letter | 12.24 | 4.29 | 16.88 | 3.98 | 5.61 | 1.13 | < .001 |

| COWAT animals | 17.61 | 4.37 | 24.66 | 4.36 | 8.10 | 1.64 | < .001 |

| COWAT m - letter & supermarket | 6.73 | 2.16 | 10.60 | 1.31 | 10.69 | 2.16 | < .001 |

| Digit span forward (WAIS–R) | 5.35 | 1.65 | 7.18 | 2.47 | 4.43 | 0.89 | < .001 |

| Digit span backward (WAIS-R) | 4.14 | 1.15 | 4.98 | 1.71 | 2.82 | 0.57 | ns |

| CTT1 [seconds] | 75.45 | 30.12 | 52.78 | 13.26 | -4.87 | -0.98 | < .001 |

| CTT2 [seconds] | 152.10 | 57.53 | 101.32 | 13.50 | -6.12 | -1.24 | < .001 |

| Spatial span forward (WMS–III) | 6.98 | 1.83 | 7.88 | 1.41 | 2.80 | 0.58 | ns |

| Spatial span backward (WMS–III) | 5.89 | 1.79 | 7.02 | 0.96 | 3.93 | 0.81 | < .001 |

| Logic memory I recall (WMS–III) | 32.33 | 8.32 | 42.72 | 4.15 | 7.44 | 1.53 | < .001 |

| Logic memory II recall (WMS–III) | 17.96 | 6.15 | 27.60 | 4.30 | 7.05 | 1.45 | < .001 |

| Logic memory II recognition (WMS–III) | 23.26 | 3.34 | 25.74 | 1.48 | 4.73 | 0.97 | < .001 |

| Logic memory II % retention (WMS–III) | 75.13 | 13.94 | 92.64 | 4.19 | 8.49 | 1.74 | < .001 |

| CVLT - TL | 44.04 | 7.79 | 51.88 | 4.17 | 6.18 | 1.26 | < .001 |

| CVLT - SDFR | 9.04 | 2.85 | 12.22 | 1.73 | 6.62 | 1.35 | < .001 |

| CVLT - SDCR | 10.83 | 2.28 | 13.55 | 1.47 | 6.98 | 1.43 | < .001 |

| CVLT - LDFR | 9.23 | 2.98 | 13.47 | 1.79 | 8.42 | 1.72 | < .001 |

| CVLT - LDCR | 10.89 | 2.38 | 14.49 | 1.51 | 8.91 | 1.82 | < .001 |

| CVLT - recognition | 14.42 | 1.41 | 15.33 | 0.80 | 3.78 | 0.77 | < .001 |

| MacNew Global | 4.20 | 0.87 | 6.22 | 0.42 | 14.65 | 2.99 | < .001 |

| MacNew Physical | 3.71 | 0.99 | 6.16 | 0.47 | 15.65 | 3.20 | < .001 |

| MacNew Emotional | 4.67 | 0.96 | 6.08 | 0.43 | 9.17 | 1.87 | < .001 |

| MacNew Social | 4.09 | 0.96 | 6.27 | 0.46 | 14.47 | 2.95 | < .001 |

Note. MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory; COWAT: Controlled Oral Word Association Test; WAIS-R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised; CTT 1 & 2: Color Trails Test; WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale III; CVLT: California Verbal Learning Test; SDFR: Short-delay free recall; SDCR: Short-delay cued recall; LDFD: Long-delay free recall; LDCD: Long-delay cued recall.

Statistical significance was obtained between the examined groups in their perceptions of quality of life as evaluated by the MacNew global scale and each subscale (Table 2). In the HF patients, the best results were obtained on the MacNew emotional subscale, while the lowest rating was obtained on the subscale assessing physical limitations. In contrast, the cardiac control group assessed the highest social HRQL and the lowest emotional HRQL.

Despite the fact that patients with diagnosed depression were excluded from the study, mean scores in the BDI-II were significantly higher than in the cardiac control group (Table 2). The average result in the HF group was 17.00 points (SD=9.8), whereas in the cardiac control group, this was 4.36 points (SD=2.69).

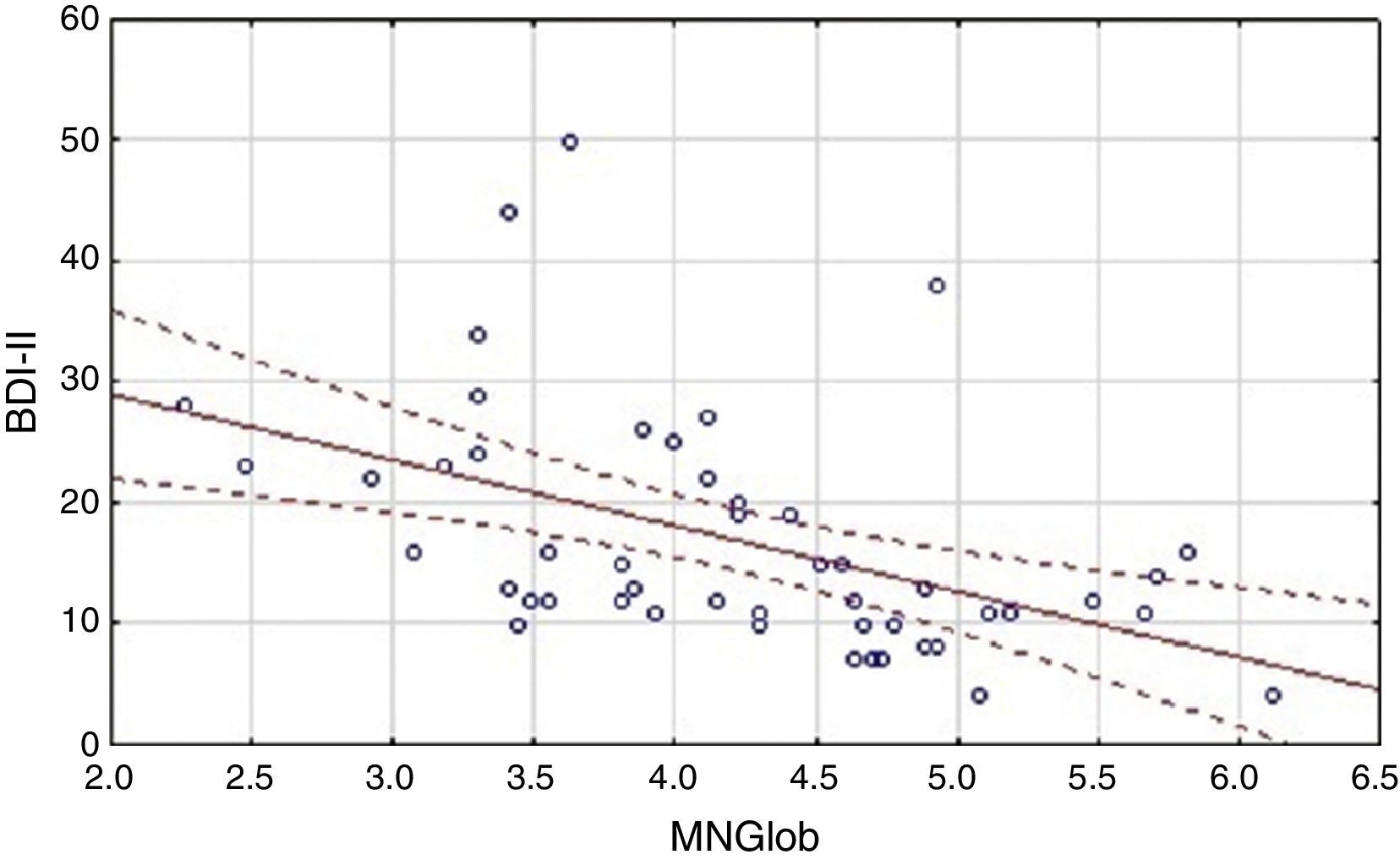

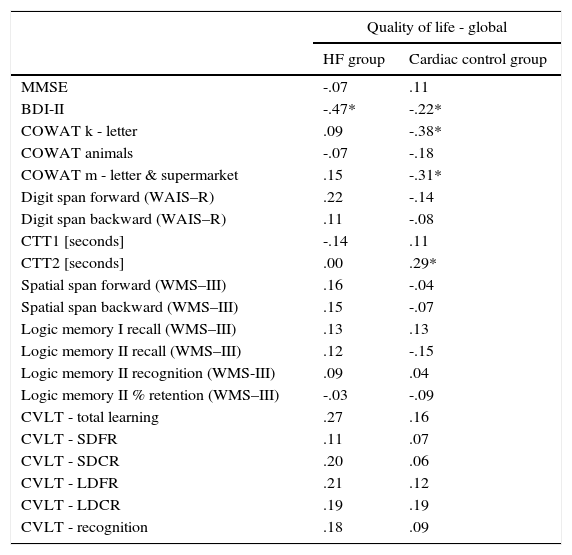

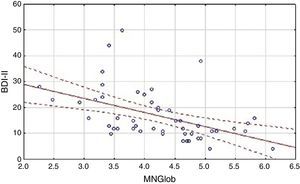

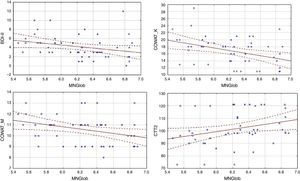

Analysis of the factors that affected an assessment of the quality of life showed differences between the HF group and the cardiac control group. Evaluation of the global quality of life in the HF group correlates negatively only with results obtained on the BDI-II scale (Table 3). Linear regressions are presented in Figure 1.

The relationship between the assessment of the quality of life and level of cognitive performance, as well as the symptoms of depression.

| Quality of life - global | ||

|---|---|---|

| HF group | Cardiac control group | |

| MMSE | -.07 | .11 |

| BDI-II | -.47* | -.22* |

| COWAT k - letter | .09 | -.38* |

| COWAT animals | -.07 | -.18 |

| COWAT m - letter & supermarket | .15 | -.31* |

| Digit span forward (WAIS–R) | .22 | -.14 |

| Digit span backward (WAIS–R) | .11 | -.08 |

| CTT1 [seconds] | -.14 | .11 |

| CTT2 [seconds] | .00 | .29* |

| Spatial span forward (WMS–III) | .16 | -.04 |

| Spatial span backward (WMS–III) | .15 | -.07 |

| Logic memory I recall (WMS–III) | .13 | .13 |

| Logic memory II recall (WMS–III) | .12 | -.15 |

| Logic memory II recognition (WMS-III) | .09 | .04 |

| Logic memory II % retention (WMS–III) | -.03 | -.09 |

| CVLT - total learning | .27 | .16 |

| CVLT - SDFR | .11 | .07 |

| CVLT - SDCR | .20 | .06 |

| CVLT - LDFR | .21 | .12 |

| CVLT - LDCR | .19 | .19 |

| CVLT - recognition | .18 | .09 |

Note. Correlation coefficient (95% correlations limits, * p< .05). MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory; COWAT: Controlled Oral Word Association Test; WAIS–R: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised; CTT 1 & 2: Color Trails Test; WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale III; CVLT: California Verbal Learning Test; SDFR: Short-delay free recall; SDCR: Short-delay cued recall; LDFD: Long-delay free recall; LDCR: Long-delay cued recall.

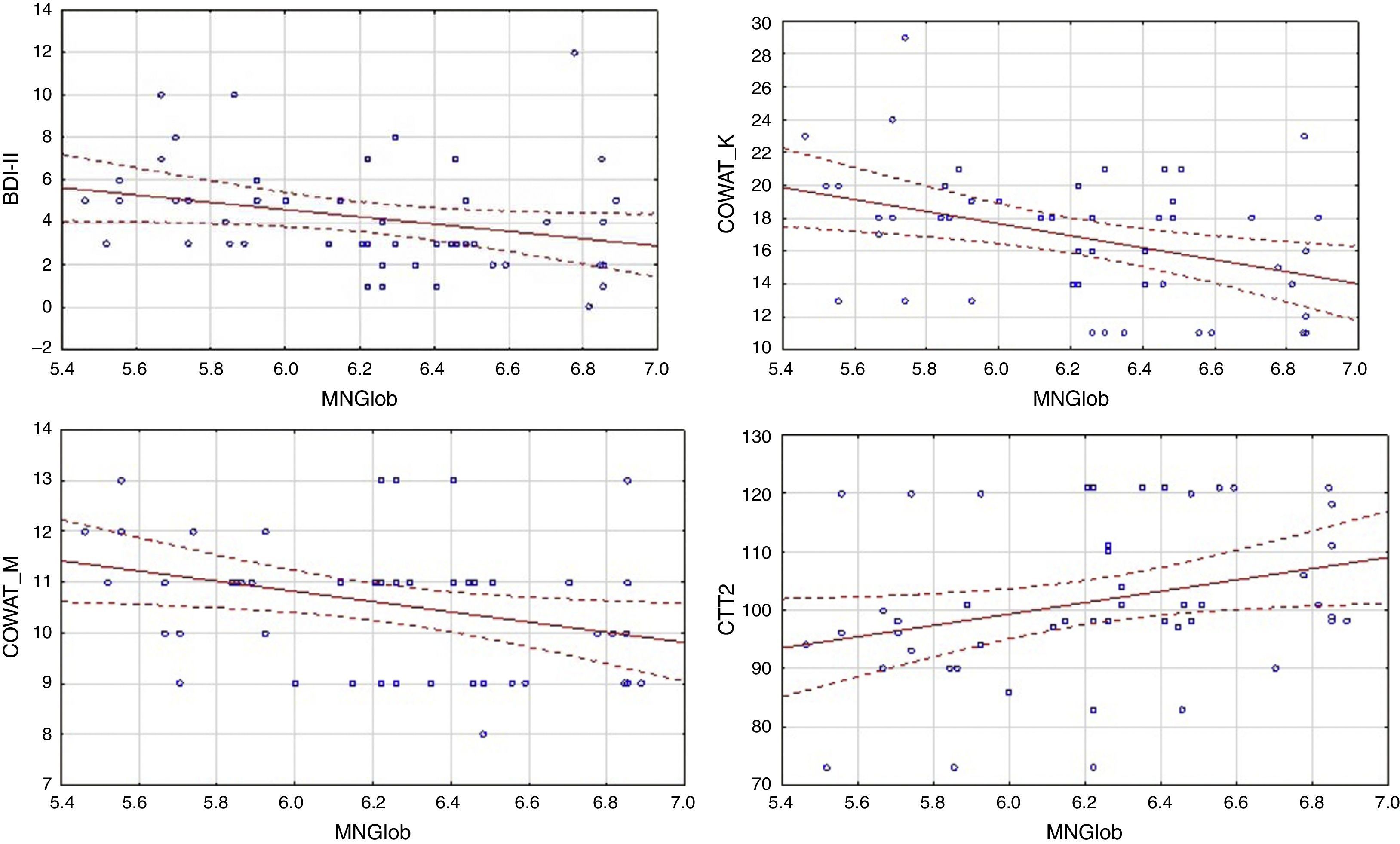

In the control group, global quality of life was associated with more factors. There was a negative correlation between global MacNew and BDI-II, as well as COWAT (k-letter), and a positive correlation with the results of CTT2 (Table 3). Linear regressions are presented in Figure 2.

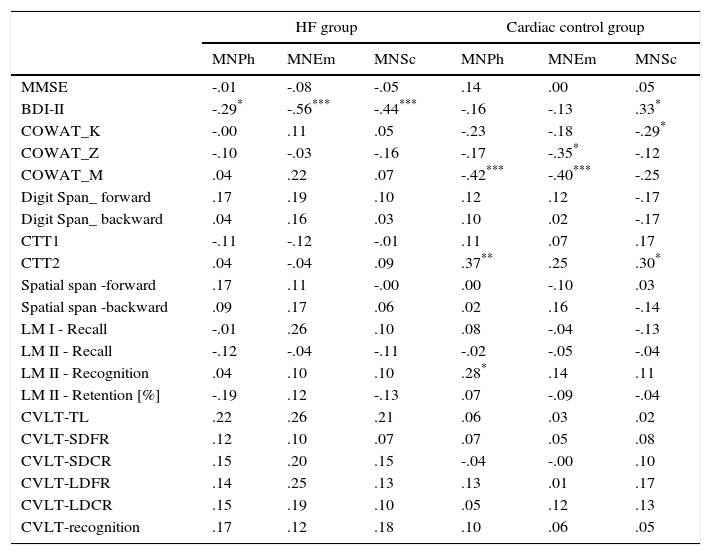

Analysis of the relationship between the results on the depression scale various dimensions of quality of life and results of the symptoms of depression, as well as cognitive tests, also showed differences between the HF group and the cardiac control group (Table 4). In the HF group, a negative correlation was observed between the results of BDI-II and all subscales of MacNew. In this group there was no relationship between the quality of life for both global performance as well as various dimensions of quality of life and cognitive performance (Tables 3 and 4). In the cardiac control group we found a correlation between the results for BDI-II and only one dimension of quality of life–the social subscale of quality of life. In this group of patients the relationship between the physical as well as emotional (but not social) dimensions of the quality of life and COWAT-M was observed. The social dimension correlated with COWAT-K. Furthermore, we found a relationship between CTT2 and the physical as well as social dimensions of quality of life. There was also a relationship between physical QoL and recognition in the logical memory test of WMS-III (Table 4).

Analysis of the relationship between the various dimensions of quality of life and results of the symptoms of depression, as well as cognitive tests in the HF group and in the cardiac control group.

| HF group | Cardiac control group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNPh | MNEm | MNSc | MNPh | MNEm | MNSc | |

| MMSE | -.01 | -.08 | -.05 | .14 | .00 | .05 |

| BDI-II | -.29* | -.56*** | -.44*** | -.16 | -.13 | .33* |

| COWAT_K | -.00 | .11 | .05 | -.23 | -.18 | -.29* |

| COWAT_Z | -.10 | -.03 | -.16 | -.17 | -.35* | -.12 |

| COWAT_M | .04 | .22 | .07 | -.42*** | -.40*** | -.25 |

| Digit Span_ forward | .17 | .19 | .10 | .12 | .12 | -.17 |

| Digit Span_ backward | .04 | .16 | .03 | .10 | .02 | -.17 |

| CTT1 | -.11 | -.12 | -.01 | .11 | .07 | .17 |

| CTT2 | .04 | -.04 | .09 | .37** | .25 | .30* |

| Spatial span -forward | .17 | .11 | -.00 | .00 | -.10 | .03 |

| Spatial span -backward | .09 | .17 | .06 | .02 | .16 | -.14 |

| LM I - Recall | -.01 | .26 | .10 | .08 | -.04 | -.13 |

| LM II - Recall | -.12 | -.04 | -.11 | -.02 | -.05 | -.04 |

| LM II - Recognition | .04 | .10 | .10 | .28* | .14 | .11 |

| LM II - Retention [%] | -.19 | .12 | -.13 | .07 | -.09 | -.04 |

| CVLT-TL | .22 | .26 | .21 | .06 | .03 | .02 |

| CVLT-SDFR | .12 | .10 | .07 | .07 | .05 | .08 |

| CVLT-SDCR | .15 | .20 | .15 | -.04 | -.00 | .10 |

| CVLT-LDFR | .14 | .25 | .13 | .13 | .01 | .17 |

| CVLT-LDCR | .15 | .19 | .10 | .05 | .12 | .13 |

| CVLT-recognition | .17 | .12 | .18 | .10 | .06 | .05 |

Note.

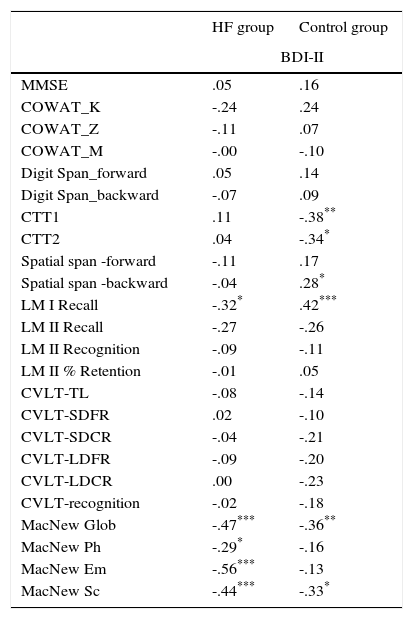

The BDI-II correlation analysis with other results has shown that in addition to a negative correlation with the scales of evaluating various aspects of quality of life, there is also a negative correlation between the BDI-II and LM-I Recall Total Score (Table 5).

Analysis of the relationship between the results of the symptoms of depression and tests of cognitive functions as well as quality of life in the heart failure group.

| HF group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| BDI-II | ||

| MMSE | .05 | .16 |

| COWAT_K | -.24 | .24 |

| COWAT_Z | -.11 | .07 |

| COWAT_M | -.00 | -.10 |

| Digit Span_forward | .05 | .14 |

| Digit Span_backward | -.07 | .09 |

| CTT1 | .11 | -.38** |

| CTT2 | .04 | -.34* |

| Spatial span -forward | -.11 | .17 |

| Spatial span -backward | -.04 | .28* |

| LM I Recall | -.32* | .42*** |

| LM II Recall | -.27 | -.26 |

| LM II Recognition | -.09 | -.11 |

| LM II % Retention | -.01 | .05 |

| CVLT-TL | -.08 | -.14 |

| CVLT-SDFR | .02 | -.10 |

| CVLT-SDCR | -.04 | -.21 |

| CVLT-LDFR | -.09 | -.20 |

| CVLT-LDCR | .00 | -.23 |

| CVLT-recognition | -.02 | -.18 |

| MacNew Glob | -.47*** | -.36** |

| MacNew Ph | -.29* | -.16 |

| MacNew Em | -.56*** | -.13 |

| MacNew Sc | -.44*** | -.33* |

Note.

In the 1970s heart failure was proposed as a possible cause of cognitive dysfunction. Soon afterwards, the term “cardiogenic dementia” appeared. Subsequently, the results of numerous studies suggested that decreased heart function, as measured by indices of low cardiac output, was independently associated with impairment in various cognitive domains (Almeida et al., 2012). These deficits are greater than those normally attributed to the normal ageing process. There are no other symptoms of dementia, such as impaired judgment or reasoning, or difficulties performing activities of daily life. Dementia usually represents a transitional state between the cognitive changes of ageing and the earliest clinical manifestations of dementia (Nordlund, Berggren, Holmstrom, Fu, & Wallin, 2015). Because of the heterogeneity of HF patients, where a variety of vascular risk factors and co-morbidity contribute to the development of cognitive decline, widely varied patterns of cognitive deficits are described in the literature (Athilingam, D’Aoust, Miller, & Chen, 2013).

In our study, we assessed memory and some aspects of the executive functions. Cognitive performance in the HF patients listed for HTx was significantly lower than in the control group made up of patients with stable CHD, without diagnosis of HF, regarding all tested functions. This is consistent with previous studies, where HF patients demonstrated poorer performance compared to healthy participants, as concerns memory, psychomotor speed and executive functioning (Levin et al., 2014; Nordlund et al., 2015). More severe HF was also associated with poorer visuospatial recall ability (Pressler et al., 2010b), which was confirmed in our study. This cognitive profile resembles the one seen in “vascular cognitive impairment”, which includes prominent executive dysfunction (Jokinen et al., 2006). But contrary to patients with vascular cognitive impairment, in the HF group, we also found extensive memory deficits. Although HF patients are at risk of cerebrovascular damage, subcortical ischemic vascular disease might therefore not be the sole explanation for the observed cognitive changes in HF patients. The finding that many patients with HF have cognitive deficits has important clinical implications, because these deficits can disrupt their ability to perform activities of daily life, and they comply with HF self-care behaviours. This is especially important in these patients, because even minor non-compliance could lead to acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) (Buck et al., 2012).

There are data highlighting the incidence of depression in patients with coronary heart disease, showing correlations between depression and mortality in patients with documented CHD, and between depression and mortality in populations with and without CHD (Dimos, Stougiannos, Kakkavas, & Trikas, 2009). In our study, patients who had been diagnosed by psychiatric assessment with depressive disorders were excluded from further study because of the impact of these disorders on cognitive functions. However, we found that the mean scores in BDI-II were higher than in the control group. This is consistent with information from other researchers, who indicated a higher incidence of depression in patients with CHD than in the general population. Significant depression has been reported in 15-22% of patients who suffer from cardiovascular disease, while 65% of the same population show mild symptoms of depression (Carney, Freedland, Sheline, & Weiss, 1997). In patients with chronic HF depression is common, with a prevalence that ranges from 13% to 77%, according to the diagnostic method used and the characteristics of the population (Angermann et al., 2011).

There is a lot of evidence to suggest that depression increases the risk of cognitive impairment regarding working memory, attention and executive dysfunction, and processing speed (Doumas, Smolders, Brunfaut, Bouckaert, & Krampe, 2012). In our study we observed that the relationship between an increase in points in BDI-II and cognitive testing concerns only the immediate memory (LM I Recall) in the HF group. However, in the cardiac control group there was a relationship between the results of BDI-II and CTT1, CTT2 and LM I Recall. Numerous studies indicate that depression may negatively impact different types of memory, including explicit, implicit, short-term, long-term and working memory (McClintock, Husain, Greer, & Cullum, 2010). Performance on verbal memory tasks may result from poor frontal-temporal lobe functioning, preoccupation with negative thoughts, or decreased processing speed (McClintock et al., 2010).

Heart failure seems to dramatically affect the quality of life in patients, since their quality of life is described as the lowest compared to patients with other chronic disorders (Garin et al., 2013; Höfer et al., 2012). A high proportion of patients with advanced HF suffer from refractory symptoms, such as breathlessness, persistent cough, fatigue, and limitation in physical activity. In addition, many patients suffer from pain, anxiety, depression, nausea and constipation (Jaarsma, Johansson, Agren, & Stromberg, 2010). Quality of life measures are useful when interventions or treatments are indicated for several reasons, such as improvement of physical functioning, pain relief, to estimate the effectiveness of therapies, and to predict mortality. Our research indicates that there is a close correlation between growing depression scale results and declining quality of life, both global and in all its dimensions in the HF group. This is consistent with the data available in the scientific literature (Gathright et al., 2015; Hwang, Liao, & Huang, 2013). Meanwhile, in the cardiac control group the results of BDI-II correlated only with global and social QoL. It seems that this reflects the negative impact of depression on social relations. It was surprising that while in the cardiac control group we observed a relationship between quality of life and executive functions, in the HF group there was no relationship between quality of life and impaired cognitive function. However, there is a relationship between quality of life and the results in BDI-II in both groups. In the case of the HF group, the presence of depressive symptoms among all the analysed symptoms is the only factor that affects quality of life.

A major limitation of the presented study is its relatively small sample size, which resulted from the fact that we aimed at a high homogeneity group, i.e. patients who had heart failure in the relative absence of other serious disorders due to HTx listing that could affect cognitive function. Additionally, we limited estimation only to certain cognitive functions. This was due to the high fatigability of patients and their poor physical condition.

In conclusion, cognitive deficits are a very common problem that affects patients with chronic HF. Memory deficits are the most common, followed by psychomotor slowing, decreased visuospatial ability and executive function. This disturbance can have a significant impact on daily functioning, and thus it should be continually monitored. There is a relationship between the severity of depressive symptoms, and the assessment of the quality of life of patients with heart failure.