Background/Objective: The objective of this ex post facto study is to analyze both the direct relationships between perceived social support, self-concept, resilience, subjective well-being and school engagement. Method: To achieve this, a battery of instruments was applied to 1,250 Compulsory Secondary Education students from the Basque Country (49% boys and 51% girls), aged between 12 and 15 years (M=13.72, SD =1.09), randomly selected. We used a structural equation model to analyze the effects of perceived social support, self-concept and resilience on subjective well-being and school engagement. Results: The results provide evidence for the influence of the support of family, peer support and teacher support on self-concept. In addition, self-concept is shown as a mediating variable associated with resilience, subjective well-being and school engagement. Conclusions: We discuss the results in the context of positive psychology and their practical implications in the school context.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio ex post facto es analizar las relaciones entre apoyo social percibido, autoconcepto, resiliencia, bienestar subjetivo e implicación escolar. Método: Se aplicó una batería de instrumentos a 1.250 estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria del País Vasco (49% chicos y 51% chicas), de entre 12 y 15 años (M=13,72, DT =1,09), seleccionados aleatoriamente. Se sometió a prueba un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales para analizar los efectos del apoyo social percibido, el autoconcepto y la resiliencia sobre el bienestar subjetivo y la implicación escolar. Resultados: Los resultados aportan evidencias a favor de la influencia que ejercen el apoyo de la familia, el apoyo de los iguales y el apoyo del profesorado sobre el autoconcepto, que a su vez se muestra como variable mediadora asociada a la resiliencia, el bienestar subjetivo y la implicación escolar. Conclusiones: Se discuten los resultados obtenidos en el marco de la psicología positiva y sus implicaciones prácticas en el contexto escolar.

Traditionally, Psychology has shown more interest in identifying problematic behaviors and human limitations than in studying our strong points (Pemberton & Wainwright, 2014). However, a new model has emerged in recent years known as Positive Youth Development. This model focuses on optimal functioning and aims to determine the individual and contextual aspects of development necessary for a healthy adolescence (Masten, 2014). In accordance with the belief that every adolescent has the potential to become a well-adjusted individual, the approach highlights the need to foster psychosocial human development in educational contexts by promoting competences that enable young people to cope successfully with their personal lives and make a positive contribution to society (Madariaga & Goñi, 2009). To this end, this study argues in favor of the healthy, well-adjusted side of adolescent development, including only positive indicators of adaptation.

Many factors are involved in an individual's successful adaptation, but during adolescence, as Bird and Markle (2012) indicate, one particularly significant indicator of psychological adjustment is subjective well-being, which encompasses one cognitive element linked to the individual's life satisfaction and two affective ones, positive affect and negative affect (Pavot & Diener, 2013; Rodríguez-Fernández & Goñi-Grandmontagne, 2011). Life satisfaction is expressed in the form of an individual's global assessment of how their life has turned out to date (Campbell, Converse & Rogers, 1976; Diener, 1994), while positive and negative affect are emotional responses to different life events that are experienced independently (Bradburn, 1969). Although research into the subject of happiness has been the focus of little attention in the field of adolescent studies (Casas, 2011), our awareness of the consequences of inadequate psychological development has given rise to the analysis of factors related to optimal adolescent psychological adjustment (Fuentes, García, Gracia, & Alarcón, 2014).

The other type of adolescent adjustment, school adjustment, refers to students’ engagement in their school environment (Li & Lerner, 2011). There is, as yet, no consensus regarding the scope and limitations of this concept, and these issues are the subject of much debate between researchers (Veiga, Burden, Appleton, Céu, & Galvao, 2014). However, a consensus has been reached regarding the definition of school engagement as a meta-construct encompassing three dimensions: cognitive, emotional and behavioral (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, Friedel, & Paris, 2005; González & Verónica-Paoloni, 2014). This variable is of vital importance to our understanding of healthy adolescent behavior (Li & Lerner, 2011; Ros, Goikoetxea, Gairín, & Lekue, 2012), since the school environment is one in which teenagers spend a great deal of their time. Furthermore, recent research has gradually provided empirical evidence regarding the existence of psychological and contextual conditions that influence adolescents’ school engagement (Christenson, Reschly, & Wylie, 2012).

One variable which bestows a certain degree of continuity on adolescent psychosocial adjustment, despite the risks inherent to that stage, is resilience (Lerner et al., 2013), a concept which has attracted a considerable amount of attention in the school field due to the key role played by these institutions as promoters of well-being (Toland & Carrigan, 2011). Many interpretations have been offered regarding this construct, which has sometimes been understood not only as a variable that facilitates adaptation, but also as an indicator of adolescent development (Masten & Tellegen, 2012). Despite the lack of consensus regarding its definition (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013), researchers increasingly agree in defining resilience as the ability to cope adequately with the developmental tasks inherent to a specific development stage, despite the risks that same stage poses (Masten, 2014). During adolescence, young people develop a set of individual and contextual characteristics that help them cope positively with stressful life events (Wright, Masten, & Narayan, 2013).

A large number of different resources are involved in adolescents’ psychosocial adaptation (Lippman et al., 2014). One of the most important of these is self-concept, understood as the set of perceptions an individual has about him or herself, based on both a personal assessment and the evaluation of significant others (Shavelson, Hubner, & Stanton, 1976). Due to its importance in psychology, self-concept has been identified as a theoretical concept closely linked to adjustment in adolescence (Rodríguez-Fernández, Droguett, & Revuelta, 2012). Its association with resilience has been documented (Kidd & Shahar, 2008), as has the dependent relationship which exists between adolescents’ subjective well-being and their self-concept (Palomar-Lever & Victorio-Estrada, 2014). Less is known, however, about the role played by self-concept in school engagement, although empirical evidence indicates that it has a direct relationship with educational variables such as students’ engagement in the learning process (Inglés, Martínez-Monteagudo, García-Fernández, Valle, & Castejón, 2014).

One of the contextual factors that has a positive impact on positive adolescent development is perceived social support (Chu, Saucier, & Hafner, 2010), understood as the individual's subjective perception of the adequacy of the support provided by their social network. This concept is a complex and dynamic one which encompasses a series of elements that interact and evolve throughout the course of adolescence (Cohen, 2004). It has been found that adolescents who perceive a greater degree of support from their family, peers and school environment have a better self-concept (Demaray, Malecki, Rueger, Brown, & Summers, 2009), and some researchers have observed a connection between social support and resilience (Wright et al., 2013), subjective well-being (Piko & Hamvai, 2010) and school engagement (Anderson, Christenson, Sinclair, & Lehr, 2004).

Evidence also exists of the influence of social support on both subjective well-being and school engagement, but with self-concept as the mediating variable (Fall & Roberts, 2012; Kong & You, 2013; Rodríguez-Fernández, Ramos-Díaz, Madariaga, Arribillaga, & Galende, 2016). Nevertheless, research analyzing both adaptation indicators in relation to their contextual and psychological variables is limited. It is important to remember that adaptive behavior during adolescence is better explained when a broad range of different factors are analyzed (Moreno & Vera, 2011). Therefore, and in light of the multi-casual nature of human behavior, an adequate explanation of personal and school adjustment should take into account both contextual and psychological variables (Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2012). Only in this way, by proposing explanatory models that include different types of factors such as environmental and individual ones, can we hope to further our understanding of adaptive behavior. Determining both the direction and the degree to which contextual and intra-individual variables influence the prediction of subjective well-being and school engagement will enable us to design psychological interventions aimed specifically at achieving good psychological adjustment and active participation in the school environment during adolescence.

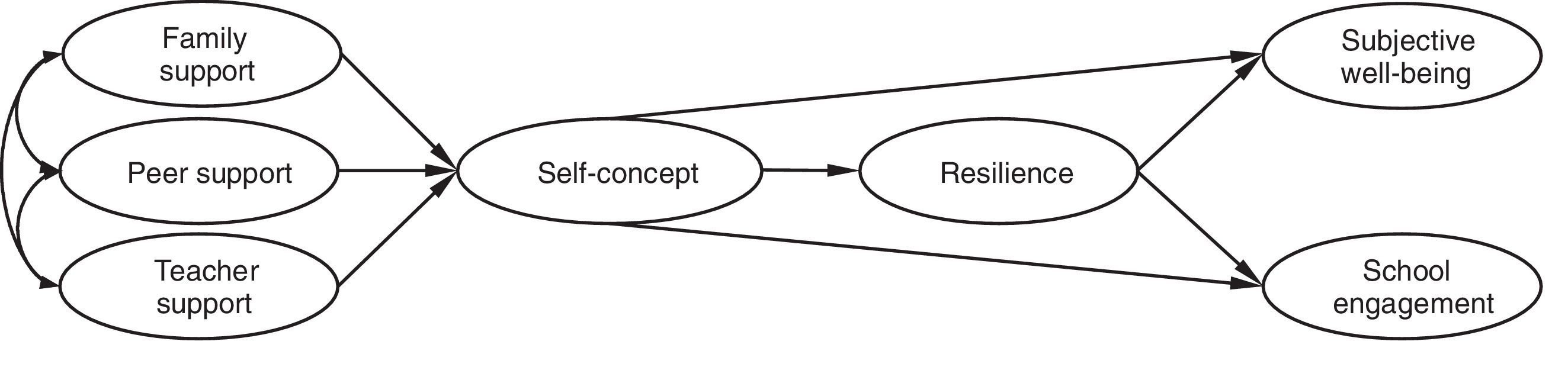

The aim of this study is therefore to test a hypothetical structural model (Figure 1) which assumes: a) the indirect influence of social support (family, friends and teachers) on subjective well-being and school engagement; b) the intervention of specific individual psychological characteristics (self-concept and resilience) as mediating elements of the influence of social support; and c) differences in the influence exerted on personal and school adjustment indicators.

MethodParticipantsA random sampling method was used, with the sample comprising a total of 1,250 secondary school students aged between 12 and 15 (Mage=13.72; SD=1.09). Of the sample, 612 (49%) were boys and 638 (51%) were girls. All participants attended schools in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country (Spain). Nine schools were selected (five public schools and four semi-private ones) with a total of 47 classes being analyzed. All school districts from which the families of participating students were drawn had a medium socioeconomic and cultural level. The students were distributed throughout the different school years as follows: 1st grade secondary school, 232 (18.6%); 2nd grade, 271 (21.8%); 3rd grade, 353 (28.2%) and 4th grade, 393 (32.4%). Pearson's chi-squared test revealed no differences in the distribution of each sex between the different grades (χ2(1)=4.66; p >.05).

InstrumentsPerceived social support was assessed on the basis of the responses given to the Family and Peer Social Support Scale (AFA-R; González & Landero, 2014), which consists of 15 statements to which participants respond on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 5=always). The scale measures social support made up of two dimensions, for which high internal consistency indexes were obtained: Family support (.84) and Peer support (.82).

Perceived support from teachers was measured using the HBSC-2006 Questionnaire by Moreno et al. (2008). The questionnaire comprises 10 factors which measure behaviors related to the health and development of adolescent school-goers. In this study, only the teacher support scale was used. The scale consists of 8 items with a 5-point Likert-type response format (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree). The Cronbach's alpha for this study was .84.

The CD-RISC 10 Resilience Scale (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) was used to measure resilience. The 10 items of this abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale Connor & Davidson, (2003) are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). When establishing the final version of the scale, the Spanish translation provided by the original authors was taken into account (Bobes et al., 2001). In this study, the internal consistency coefficient obtained was .78.

Self-concept was evaluated using the Dimensional Self-Concept Questionnaire (AUDIM; Fernández-Zabala, Goñi, Rodríguez-Fernández, & Goñi, 2015). The questionnaire has a 5-point Likert-type response scale (1=false, 5=true) and comprises 33 items. It has 12 scales which assess different dimensions of self-concept, as well as a general self-concept scale which was the one used in this analysis. The Cronbach's alpha for this study was .82.

The Spanish version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985), validated by Atienza, Pons, Balaguer and García-Merita (2000), was used to evaluate life satisfaction. This scale measures global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one's life on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree). The reliability coefficient obtained for the present study was .83.

Positive and negative affect were measured using the Affect Balance Scale (ABS; Bradburn, 1969) revised by Warr, Barter and Brownbridge (1983). The scale comprises 18 items (9 to assess positive affect and 9 to assess negative affect), to which responses are given on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 4=all the time). The Spanish version of the scale, validated by Godoy-Izquierdo, Martínez and Godoy (2008), was used here. The Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients obtained with our sample were: Positive affect (.80) and Negative affect (.78).

School engagement was evaluated using the authors’ Spanish translation of the School Engagement Measurement (SEM; Fredricks et al., 2005). The measure consists of 19 items to which participants respond on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=never, 5=very true) and comprises three factors which measure behavioral, emotional and cognitive engagement. In this study, the indexes obtained were: Behavioral engagement (α=74), Emotional engagement (α=81) and Cognitive engagement (α=77).

ProcedureParticipants were selected randomly. After a random selection of various secondary schools from the list of all secondary schools in the Autonomous Region of the Basque Country (ARBC), a number of classes were selected from each. The management teams of the selected schools were contacted in order to explain the research project and ask for their voluntary cooperation. Two schools declined the invitation to collaborate in the project, and two new schools were selected to replace them, using the same random selection procedure described above. Informed consent forms were sent out to parents and students, along with a letter explaining the research project. After obtaining the necessary authorization from the school management teams, two researchers administered the battery of tests to students during a regular class period. The tests were administered simultaneously to all students in each selected classroom, in order to ensure uniformity. The order in which the instruments were administered was counterbalanced in each school, and the mean time taken to respond to the full questionnaire was 45minutes. With the aim of mitigating the incidence of responses in keeping with the research hypothesis, the single blind criterion was employed (i.e. students were unaware of the purpose of the study). The anonymity of responses was guaranteed, and participation was on a strictly voluntary basis. None of the students refused to participate in the research project. The study met the standards set by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación y Docencia at the Universidad del País Vasco (UPV-EHU).

Data analysisThe structural regression model analysis indicated compliance with the assumptions of multivariate normality. In the case of missing values (2.1%), using the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm and the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), an approximate score was extracted for each missing item, based on the response pattern. The multivariate normality analysis was conducted and extreme values were eliminated (1.3%), with the normal distribution being verified using Mardia's coefficient, which was found to be adequate (M=37.12<70) in accordance with the criteria established by Rodríguez and Ruiz (2008).

To confirm the hypothesized model, the Structural Equations Model (SEM) technique was used, and the analyses were carried out using the maximum likelihood procedure. Various different indexes have been proposed for testing a model's fit (Byrne, 2001), including the chi-squared statistic (χ2) and its associated probability level. Due to the sensitivity of the χ2 statistic to sample size (Barrett, 2007), other indexes of fit have also been proposed, such as the GFI (Goodness of Fit Index), the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and the TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), the recommendation being that all should obtain values of over .90 (Kline, 2011). Moreover, the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) indexes were also used. In these indexes, values lower than .08 are indicative of acceptable fit, while values of .05 or less indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The complete structural regression model contains seven latent variables, the indicators of which are: a) in the case of social support (family support, peer support and teacher support variables), self-concept and resilience, the items of the corresponding test scales; and b) in the case of the subjective well-being variables (life satisfaction and positive and negative affect) and school engagement (cognitive, emotional and behavioral engagement), the scores obtained by participants in the different scales (parcels technique).

The following statistical programs were used: LISREL 8.8 for imputing missing values; SAS for the multivariate normality analysis and the detection of outliers and strange response patterns; SPSS 22 for the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients; and AMOS 21 for testing the structural regression model.

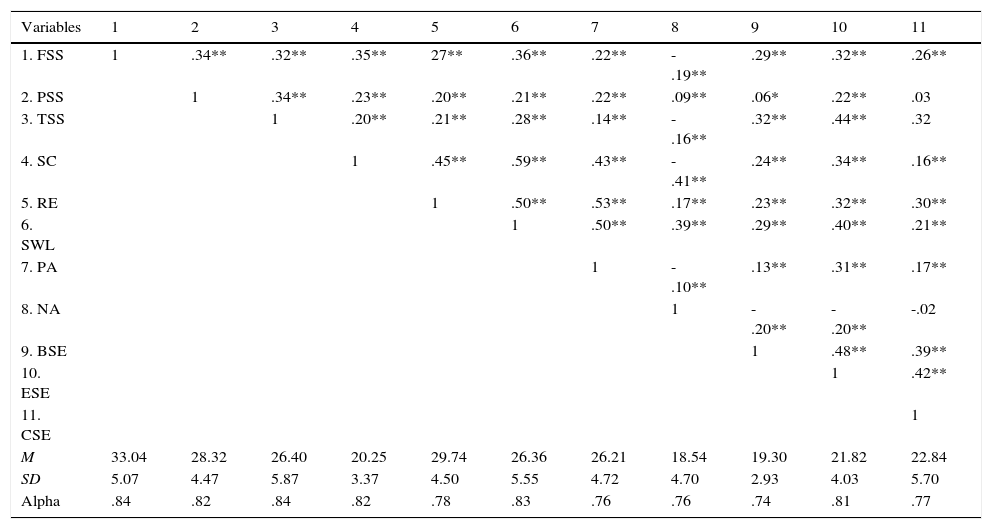

ResultsDescriptive statistics and correlations between the study variablesPrior to the analysis of the structural regression model, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between the study variables, as well as for the means and standard deviations. Of the data presented in Table 1, it is worth pointing out that the negative affect and behavioral engagement levels were fairly low, and that the highest score obtained was for family support. The correlation matrix reveals the existence of significant interrelations between all the variables at the p<.01 or p<.05 level, with the exception of cognitive engagement, which did not correlate significantly with either peer support (r=.03, p>.05) or teacher support (r=.32, p>.05). The highest direct relationship indexes were observed between self-concept and life satisfaction (r=.59, p<.01), and between resilience and life satisfaction (r=.50, p<.01). Taking the Pearson correlation coefficient as the effect size measure (Sánchez-Meca, 2008), the majority of the statistically significant correlations observed have a medium-high effect size.

Means, standard deviations, alphas and bivariate correlations between all study variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FSS | 1 | .34** | .32** | .35** | 27** | .36** | .22** | -.19** | .29** | .32** | .26** |

| 2. PSS | 1 | .34** | .23** | .20** | .21** | .22** | .09** | .06* | .22** | .03 | |

| 3. TSS | 1 | .20** | .21** | .28** | .14** | -.16** | .32** | .44** | .32 | ||

| 4. SC | 1 | .45** | .59** | .43** | -.41** | .24** | .34** | .16** | |||

| 5. RE | 1 | .50** | .53** | .17** | .23** | .32** | .30** | ||||

| 6. SWL | 1 | .50** | .39** | .29** | .40** | .21** | |||||

| 7. PA | 1 | -.10** | .13** | .31** | .17** | ||||||

| 8. NA | 1 | -.20** | -.20** | -.02 | |||||||

| 9. BSE | 1 | .48** | .39** | ||||||||

| 10. ESE | 1 | .42** | |||||||||

| 11. CSE | 1 | ||||||||||

| M | 33.04 | 28.32 | 26.40 | 20.25 | 29.74 | 26.36 | 26.21 | 18.54 | 19.30 | 21.82 | 22.84 |

| SD | 5.07 | 4.47 | 5.87 | 3.37 | 4.50 | 5.55 | 4.72 | 4.70 | 2.93 | 4.03 | 5.70 |

| Alpha | .84 | .82 | .84 | .82 | .78 | .83 | .76 | .76 | .74 | .81 | .77 |

Note. * p<.05; ** p<.01. FSS: Family social support. PSS: Peer social support. TSS: Teacher social support. SC: Self-concept. RE: Resilience. SWL: Satisfaction with life. PA: Positive affect. NA: Negative affect. BSE: Behavioral school engagement. ESE: Emotional school engagement. CSE: Cognitive school engagement.

The resulting parameters indicate that the initial model does not entirely fit the empirical data (Figure 2), although it is close to being reasonable bearing in mind its complexity (χ2(891)=3660.63; p<.001; GFI=.877; CFI=.848; TLI=.838; SRMR=.55; RMSEA=.50). The interpretation of these parameters and the resulting path analyses suggest that it would be a good idea to re-specify the model and evaluate it once again.

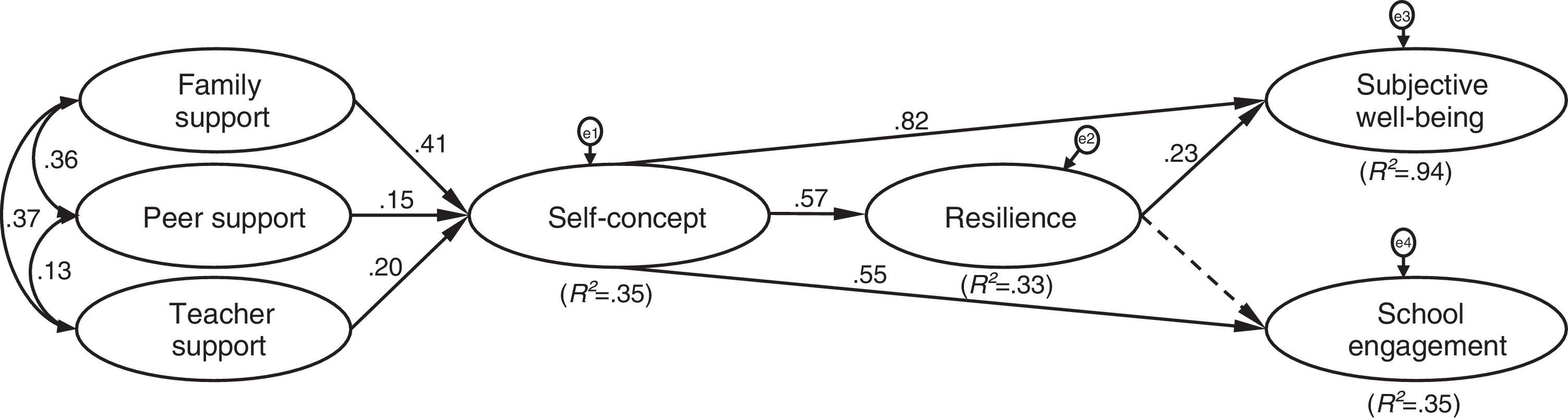

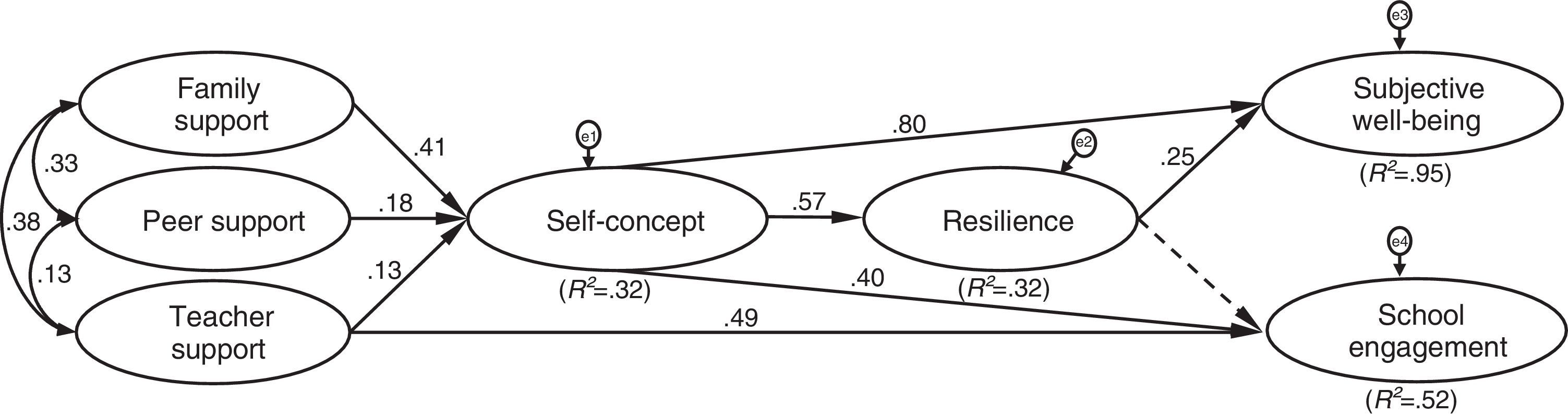

Firstly, items 9 (λ=.30; t=9.69, p<.01) and 10 (λ=.28; t=9.30, p<.01) were eliminated from the Social Support Questionnaire due to their low factor loading, along with the non-significant relationship between resilience and school engagement. Moreover, in accordance with the suggestions of the Lagrange Multiplier Test (Bentler, 2006), the teacher support-school engagement path, for which a theoretical basis has been found (García-Bacete, Ferrà, Monjas & Marande, 2014) was added. Finally, the analysis of the modification indexes suggested the incorporation of four error covariances that are justified by semantic similarities detected in the drafting of item pairs belonging to the Social Support Questionnaire, with a change in the standardized parameter of .21, .08, .12 and .23, respectively.

After incorporating the aforementioned re-specifications, the final model presented in Figure 3 was established. Once again, although the chi-squared value is significant (χ2(764)=2364.09 p<.001), indicating a lack of fit between the model and the data, the values obtained for the other indicators were adequate (GFI=.912; CFI=.908; TLI=.901; SRMR=.45; RMSEA=.041). Thus, given that the acceptance of any model is determined by multiple indicators (Hu & Bentler, 1999), we can assert that the proposed model correctly fits the empirical data.

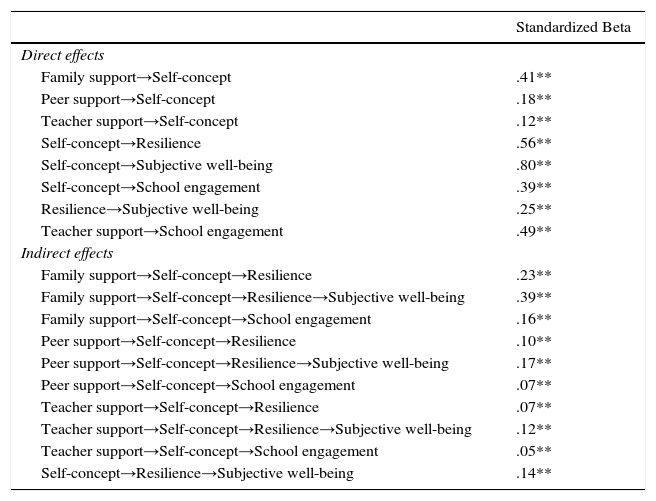

Direct and indirect effects between the study variablesIf the final model's regression coefficients are analyzed individually (Table 2), it becomes clear that almost all the proposed paths obtained significance level (p<.01), with the exception of the resilience-school engagement pair. Thus, the three sources of social support were found to predict 32% of the self-concept variable, with family support having the strongest predictive capacity (β=.41, p<.01). For its part, resilience is directly determined by self-concept (β=.56, p<01). As regards adaptation indicators, subjective well-being was observed to be directly explained by self-concept (β=.80, p<.01) and resilience (β=.25, p<.01); although school engagement was only explained by self-concept (β=.39, p<01), not by resilience (β=.00, p< .01). Teacher support, on the other hand, was observed to have a direct effect on school engagement (β=.49, p<01).

Standardized direct and indirect effects between study variables.

| Standardized Beta | |

|---|---|

| Direct effects | |

| Family support→Self-concept | .41** |

| Peer support→Self-concept | .18** |

| Teacher support→Self-concept | .12** |

| Self-concept→Resilience | .56** |

| Self-concept→Subjective well-being | .80** |

| Self-concept→School engagement | .39** |

| Resilience→Subjective well-being | .25** |

| Teacher support→School engagement | .49** |

| Indirect effects | |

| Family support→Self-concept→Resilience | .23** |

| Family support→Self-concept→Resilience→Subjective well-being | .39** |

| Family support→Self-concept→School engagement | .16** |

| Peer support→Self-concept→Resilience | .10** |

| Peer support→Self-concept→Resilience→Subjective well-being | .17** |

| Peer support→Self-concept→School engagement | .07** |

| Teacher support→Self-concept→Resilience | .07** |

| Teacher support→Self-concept→Resilience→Subjective well-being | .12** |

| Teacher support→Self-concept→School engagement | .05** |

| Self-concept→Resilience→Subjective well-being | .14** |

Note. **p<.01. R2(Self-concept)=.32; R2(Resilience)=.32; R2(Subjective well-being)=.95; R2(School engagement)=.52.

As regards the indirect effects on the adjustment indicators, the results indicate that family, peer and teacher support had an indirect effect on subjective well-being, mediated by the subject's level of positive self-concept. Moreover, if the resilience path is added to this, it functions as a mediating variable of self-concept, with there being a two-fold mediation effect between subjective well-being and family support (β=.39, p<.01), peer support (β=.17, p<01) and teacher support (β=.12, p<.01). Finally, the results reveal that school engagement is directly influenced by teacher support (β=0.49, p<0.01) and indirectly influenced by social support (family: β=.16, p<.01; peers: β=.07, p<.01; teacher: β=.05, p<.01), through self-concept.

In short, social support from family, peers and teachers, while not directly influencing psychosocial adjustment, does activate the psychological variables (self-concept, directly, and resilience, indirectly) that have a direct impact on subjective well-being (R2=.95) and school engagement (R2=.52), with the exception of resilience that does not directly explain school engagement. Self-concept also influences subjective well-being indirectly, through resilience. In other words, the relationship between the contextual factors studied and both adaptation indicators is mediated by self-concept, which also has a direct influence on resilience. Finally, teacher support has both a direct effect on school engagement and an indirect one through self-concept.

DiscussionGrowing interest in positive development during adolescence and the potential of schools for fostering this development have impacted the current predominant view of adolescent adaptive behavior as a multi-causal phenomenon (Masten, 2014). The aim of this study was to empirically verify a structural regression model in which psychological and contextual factors influence subjective well-being and school engagement, understood as measures of psychosocial adjustment.

The results reveal the important role played by self-concept and resilience, in combination with social support, in predicting well-adapted behavior, as suggested by the initial hypothetical model proposed. However, the intra-individual variables (self-concept and resilience) were found not to influence the two adjustment indicators in the hypothesized manner. The strongest relationship was observed between self-concept and subjective well-being, with self-perceptions having a positive influence on students’ engagement also, while resilience is particularly important for predicting personal adjustment, but appears to have no impact whatsoever on school adjustment. If the weight of the influence exerted by the factors included in the model are compared, it becomes clear that although the variables that best explain subjective well-being are psychological in nature, the same cannot be said of school engagement, which is mainly determined by teacher support. This direct effect (i.e. teacher support on school engagement) was not contemplated in the hypothetical model, which posited an influence of teacher support that was fully mediated by psychological variables.

People's psychological and social functioning is greatly influenced by their interactions with the environment or context in which they live. Within the ecological environment in which adolescents exist, close links have been confirmed between feeling supported by one's social network and the subjective perception of well-being (Ronen, Hamama, Rosenbaum, & Mishely-Yarlap, 2014). Similarly, research has also demonstrated the major impact of the contextual systems in adolescents’ most immediate environments on their engagement, with the family, peer and school systems being of particular importance (Estell & Perdue, 2013). Moreover, the influence of parents and teachers fosters adolescents’ engagement in healthy extracurricular activities (Olivares, Cossio-Bolaños, Gomez-Campos, Almonacid-Fierro, & Garcia-Rubio, 2015).

In this complex web of connections, the role played by these contextual variables regarding subjective well-being and school engagement has yet to be fully determined, as have their direct and indirect relationships with other variables linked to psychosocial adjustment. A previous piece of research in the same field (Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2012) found that family support indirectly explained life satisfaction and school adjustment through self-concept, while peer support mediated by the same psychological variable had no influence on either of the two adaptation indicators. The results of the present study partly confirm this finding, since they corroborate the indirect influence of both family and peer support on subjective well-being and school engagement, while at the same time adding a third source of social support, namely teachers, into the mix. Indeed, one of the most relevant contributions of this paper is the direct effect observed between teacher support and school engagement. This finding points to the need to recognize the key role played by teachers and provides empirical support for the need to help shape teachers’ attitudes towards their students, as well as to improve the help and support they provide during the learning process and adolescents’ adaptation to the school context.

Self-concept is known to serve as a mediating agent between the environment and adolescent development (Rodríguez-Fernández et al., 2012). This study not only provides evidence of the way in which self-concept mediates between social support and the indicators of personal and school adaptation, it also incorporates another new psychological variable into this relational structure, namely resilience. The fact that both intra-individual variables studied depend on social support systems and in turn exercise influence on subjective well-being (with self-concept also exercising an individual influence on school engagement), points to the need for both schools and families to provide adolescences with a good social support network in order to ensure their adaptive functioning. This improvement in psychological, contextual and educational variables would be accompanied by a reduction in aggressive behaviors such as cyberbullying (Álvarez García, Nuñez-Pérez, Dobarro González, & Rodríguez Pérez, 2015).

The results have educational implications that point to the importance of fostering psychosocial development in the school environment through education based on positive coping with adversity and acceptance of oneself in order to achieve happiness. They also highlight the importance of good teacher-student relations in fostering school adaptation. In general, the conclusions drawn offer some interesting ideas for professional practice, specifically as regards how to optimize psychological intervention programs in the educational field, placing greater emphasis on connecting context and intra-individual characteristics with the adaptive functioning of adolescents, in order to foster the competences required to improve students’ well-being.

As regards the limitations of the study, the use of self-report measures rather than objective tests may be something to be redressed in future work. In this sense, future research should include a design that takes into account the different effect of the variables analyzed when the information stems from other sources, such as teachers, classmates or parents. Similarly, it is worth highlighting the fact that the results presented here refer to adolescent students aged between 12 and 15. Consequently, the sample group used in the study precludes the generalization of the results to populations located outside this age range and educational level. With the aim of enabling the results to be generalized more widely and subjecting the model obtained to stricter testing, future research may wish to use a multi-sample analysis contemplating educational level, sex and/or socioeconomic-cultural stratum. This type of design will provide information about the weight of the variables in relation to adolescents’ psychological and social adjustment in each sample group analyzed. Finally, it should be made clear that the methodology used in the study, while advanced, is nevertheless still crosscutting, and the model needs to be subjected to testing with longitudinal data before we can begin to talk about true dependence between variables.

FundingThe authors of this study are part of the Consolidated Research Group IT701-13 of the Basque University System. The study was carried out as part of the research project EHUA 15/15 at the University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU).