According to existing evidence, parental educational practices and social anxiety are to some degree connected. However, the possibility that this relationship is an indirect one and is mediated by individual factors such as self-esteem or emotional regulation has not yet been explored. The aim of this study was therefore to explore the relationship between maternal and paternal educational practices and social anxiety, and test both the direct and the indirect pathways. Method: The representative sample consisted of 2,060 Andalusian students (47.7% girls, Mage=14.34) who filled in various self-reports. Results: The structural equation models confirmed that a direct relationship, with a low effect size, exists between parental educational practices and social anxiety and that there is also an indirect relationship, mediated by negative self-esteem and emotional suppression (the emotional regulation strategy), which accounted here for 49.1% of the variance in social anxiety. Conclusions: Parental education practices seem to act as a family asset which either promotes or hinders the development of basic attitudes and competencies such as self-esteem or emotional regulation and, by doing this, either encourages or prevents the emergence of problems such as social anxiety.

La evidencia previa ha demostrado una modesta relación entre las prácticas educativas parentales y la ansiedad social. No se ha explorado, sin embargo, la posibilidad de que dicha relación sea indirecta y se encuentre mediada por factores individuales como la autoestima o la regulación emocional. Consecuentemente, el objetivo de este estudio ha sido conocer la relación entre las prácticas educativas maternas y paternas y la ansiedad social, testando tanto la vía directa, como la indirecta. Método: La muestra representativa estuvo compuesta por 2.060 estudiantes andaluces (47,7% chicas; Medad=14,34) que completaron distintos autoinformes. Resultados: Los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales confirmaron una relación directa entre las prácticas educativas parentales y la ansiedad social con un bajo tamaño del efecto y también una relación indirecta mediada por la autoestima negativa y la estrategia de regulación emocional, supresión emocional, que consiguió explicar hasta un 49,1% de la varianza de la ansiedad social. Conclusiones: Las prácticas educativas parentales parecen actuar como un activo familiar que promueve o dificulta el desarrollo de actitudes y competencias fundamentales como son la autoestima o la regulación emocional y, a través de ellas, favorece o previene la aparición de problemas como la ansiedad social.

The defining feature of social anxiety disorder is an excessive fear in response to social situations in which the person believes they may be judged and negatively evaluated by others (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). It is one of commonest disorders among young people (Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, 2015) and its implications reach further than the distress it causes – it is a serious problem which limits the social adaptation of young people who are affected by making them avoid different social interactions (Knappe, Sasagawa, & Creswell, 2015). However, the problem is often undiagnosed and, therefore, often goes undertreated: knowing the factors associated with the etiology and development of social anxiety would therefore help us to establish the key steps towards preventing it.

Although the determining factors are individual in nature (Nunes, Ayala-Nunes, Pechorro, & La Greca, 2018; Olivares-Olivares, Ortiz-González, & Olivares, 2019), a number of contextual factors are undoubtedly involved, too. Here, special attention has been paid to the family, and most of the studies have been focused on examining the parents’ mental health or the parental behaviour which is linked to organising their social life (Knappe et al., 2009). The literature available on the educational practices of parents of children with social anxiety stresses the important role of overprotection, excessive criticism or rejection, as well as lack of parental affection. These factors have been studied both individually and jointly, through the construct of “expressed emotion”, in a sample of subjects who have been clinically diagnosed with social anxiety (García-López, Díaz-Castela, Muela-Martínez, & Espinosa- Fernández, 2014).

When each of these is analysed individually, the importance of maternal overprotection is highlighted (Knappe, Beesdo-Baum, Fehm, Lieb, & Wittchen, 2012; Rork & Morris, 2009; Xu, Ni, Ran, & Zhang, 2017). Some authors, in fact, consider that this factor outweighs the importance of the deficit of affection in the development and suffering of anxiety problems, and makes them chronic (Rapee, 1997). The role of constant criticism as a potential parental predictor of social anxiety has also been stressed (Rork & Morris, 2009). Here, it is common to find parents of young people with social anxiety who put more emphasis on telling them what not to do than on guiding them to use socially appropriate behaviour, which has been called a negativist style (Gulley, Oppenheimer, & Hankin, 2014). These practices are often accompanied by deficient, negative communication patterns (Hummel & Gross, 2001) and less emotional warmth, especially from the father figure (Knappe et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2017).

The study by Gómez-Ortiz, Casas, and Ortega-Ruiz (2016) looks into other less commonly studied parental practices, such as behavioural and psychological control (the former refers to obtaining information about the child through direct questions seeking to impose obligatory boundaries, while the latter appears in the use of manipulative and intrusive strategies such as inducing a feeling of guilt or withdrawing their affection as a way of controlling the child). The study focuses on practices in which the child is made to voluntarily disclose information to the parent and on the discipline practices involved in maternal supervision. All of these, especially psychological control, are described as risk factors related to the presence of social anxiety - apart from those which encourage disclosure, which is interpreted as a protection factor.

The available evidence seems to suggest that the family is an important study context in the development of social anxiety. However, it is necessary to define the role played by the different parental educational practices. Although previous studies have examined the direct relationship between the latter and social anxiety, showing a low effect size in the relationship (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2016), the possible indirect relationship between parental practices and anxiety, mediated by individual qualities such as self-esteem or emotional regulation, has not been explored so far. These factors have revealed a close relationship with both social anxiety (Caballo, Salazar, & CISO-A research team in Spain, 2018; Gómez-Ortiz, Roldán, Ortega-Ruiz, & García-López, 2018; Jazaieri, Morrison, Goldin, & Gross, 2015; Kivity & Huppert, 2018; Tuijl, de Jong, Sportel, de Hullu, & Nauta, 2014Van Tuijl et al., (2014)) and parental educational styles (García, Serra, Zacarés, & García, 2018; Turpyn, Chaplin, Cook, & Martelli, 2015). In fact, these variables seem to play a mediating role in explaining various problems of psychosocial adjustment in children and adolescents, such as depression, anxiety or aggression, and seem to be a result of parental styles which condition the adjustment indicators evaluated (Bozicevic et al., 2016; Wouters, Colpin, Luyckx, & Verschueren, 2018). However, the role this pathway of influence plays in adolescent social anxiety has not been tested. In addition, previous studies have also shown that the parent's gender is an important factor which conditions the results obtained in the relationship between parental practices and social anxiety (Knappe et al., 2012; Rapee, 1997, Rork & Morris, 2009; Xu et al., 2017). This stresses the importance of clarifying the possible differences apparent in this relationship depending on the type of educational practice observed and the parent's gender.

The purpose of this study was to explore the possible relationship between maternal and paternal educational practices from the viewpoint of an adolescent and their own social anxiety. This leads us to two specific objectives: (1) to analyse the direct relationship between maternal and paternal practices and social anxiety, and (2) to explore the mediating nature of negative self-esteem and emotional suppression in this relationship. To achieve this, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: We expect there to be a direct relationship, with a medium-low effect size, between maternal and paternal practices and suffering social anxiety, in line with the findings of previous studies (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2016).

H2: We expect that an indirect relationship can be established between maternal and paternal educational practices and adolescent social anxiety, which is mediated through negative self-esteem and emotional suppression. A considerable body of research, focused on the study of depression, general anxiety or aggression, supports the existence of such a pathway of influence (Bozicevic et al., 2016; Wouters et al., 2018), although it has not been tested in relation to social anxiety. We expect that affect and communication, the promotion of autonomy and humour are all negatively associated with the mediating variables and that parental psychological control is positively related to them. These relationships have already been mentioned in previous research (García et al., 2018, Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2016, Turpyn et al., 2015). Similarly, we expect to find that these mediating variables are linked positively to social anxiety, as shown in the studies by Gómez-Ortiz et al. (2018), Kivity and Huppert (2018) and Van Tuijl et al., (2014) .

H3: We predict that the parent's gender will condition the results obtained, as suggested by previous evidence (Knappe et al., 2012; Rapee, 1997; Rork & Morris, 2009; Xu et al., 2017).

MethodParticipantsThis study was carried out in a reference population of a group of schoolchildren (368,838 students) attending Obligatory Secondary Education (ESO, in Spanish) in Andalusia, a region in southern Spain. We carried out a probabilistic, stratified random sampling by conglomerates, with a single stage with proportional allocation. The strata established were the geographical area (Eastern Andalusia vs. Western Andalusia), the type of school ownership (private vs. public) and the size of population of the town where the school was located (<10,000 inhabitants, 10,001-100,000 inhabitants and> 100,000 inhabitants). A 95.5% confidence level and a 2.5% sampling error were set, assuming the greatest variability (p=q=0.5) (Cea D́Ancona, 1996). The final sample was made up of 2,060 schoolchildren from Obligatory Secondary Education (52.1% boys). The participants were aged between 12 and 19 years old (M=14.34, SD=1.34). 48.2% of the schoolchildren belonged to the eastern area of Andalusia and 51.8% to the west. 37.1% attended schools in towns with under 10,000 inhabitants; 30.9% in towns with between 10,001 and 100,000 inhabitants and 32% in cities with over 100,000 inhabitants. Finally, 66.8% went to state schools and 33.2% private schools.

InstrumentsThe Scale of Social Anxiety for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998): this instrument, which has been validated for the Spanish adolescent population by Olivares, Ruiz, Hidalgo, García-López, Rosa, and Piqueras (2005), consists of 22 items with answers on a Likert scale, with five response options to mark how often the symptoms appear (1=not at all, 5=all the time). It evaluates three dimensions of social anxiety: Fear of negative evaluation (FNE; e.g., “I’m worried about what other people think of me”); Social avoidance and anguish in new situations (AANS; e.g., “I get nervous when I meet new people”); and Social avoidance and general anguish (AGA, e.g., “I feel shy even when I’m with classmates I know very well”). The scale has shown sound internal consistency in this study, both on a general level (α=.90) as well as in its dimensions: αFNE=.87; αAANS=.83; y αAGA=.77.

The Evaluation Scale of the Educational Style of Fathers and Mothers of Adolescents (Oliva, Parra, Sanchez-Queija, & López, 2007): this scale consists of 82 items (41 on the mother's educational style and 41 on the father's), answered on a Likert scale with six response options (1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree). It assesses six dimensions of educational style: Affection and communication (e.g., “He/she enjoy talking with me about things”), Behavioural control (e.g., “He/she asks me what I spend my money on”), Psychological control (e.g., “He/she's always telling me what to do”), promotion of autonomy, (e.g., “He/she encourages me to take my own decisions”), Humour (e.g., “He/she usually shares jokes with me”) and Filial disclosure (e.g., “I tell him/her what I get up to in my free time”). In this study, the scale has shown a sound internal consistency both on a general level (α=.94) and in each of the dimensions: Affection and communication (αmother=.89; αfather=.90), Behavioural control (αmother=.82; αfather=.84), Psychological control (αmother=.78; αfather=.81), Promotion of autonomy (αmother=.83; αfather=.81), Humour (αmother=.81; αfather=.84) and Filial disclosure (αmother=.87; αfather=.86).

The Scale of Negative Self-esteem, adapted from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965): this scale consists of four items related to negative self-assessment, answered on a Likert scale 1-4 (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). In the current study, the scale showed an acceptable internal consistency (α=.76) and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indices reflected a good fit: X2S-B=6.43; G.L.=2; p=.04; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.03 (IC:.006–.064).

The Emotional Suppression Scale, adapted from the Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003), consisting of four items answered on a Likert scale which offer seven response options (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree). In the current study, the scale showed an acceptable internal consistency (α=.70) and the CFA indices reflected a good fit: X2S-B=6.43; G.L.=2; p=.04; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.03 (IC:0.006–0.064).

ProcedureThe research has a retrospective ex-post-facto design (Montero & León, 2007). The study was approved by the University of Córdoba Bioethics and Biosafety Committee and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical standards. We asked the school heads for permission and the participant's families gave their consent. The average time taken to complete the items ranged between 45 and 60minutes.

Data analysisTo confirm the factorial structure of the negative self-esteem and emotional suppression scale, we carried out a CFA. The results of this analysis can be seen in the ‘Instruments’ section. To check the hypotheses, Spearman correlations were performed between the different study variables, and structural equation models (SEM) were made up differentially, according to the educational practices of the parents, following the recommendations given by Oliva et al. (2007). Taking into account the ordinal nature of the questionnaire variables, the Weighted Least Square estimation method with robust correction was used in the SEM and CFA (Bryant & Satorrra, 2012). To assess the adjustment of the model, the following indices were considered: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) (values equal to or over .95 indicate a good adjustment), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (values below .08 indicate a good fit) (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

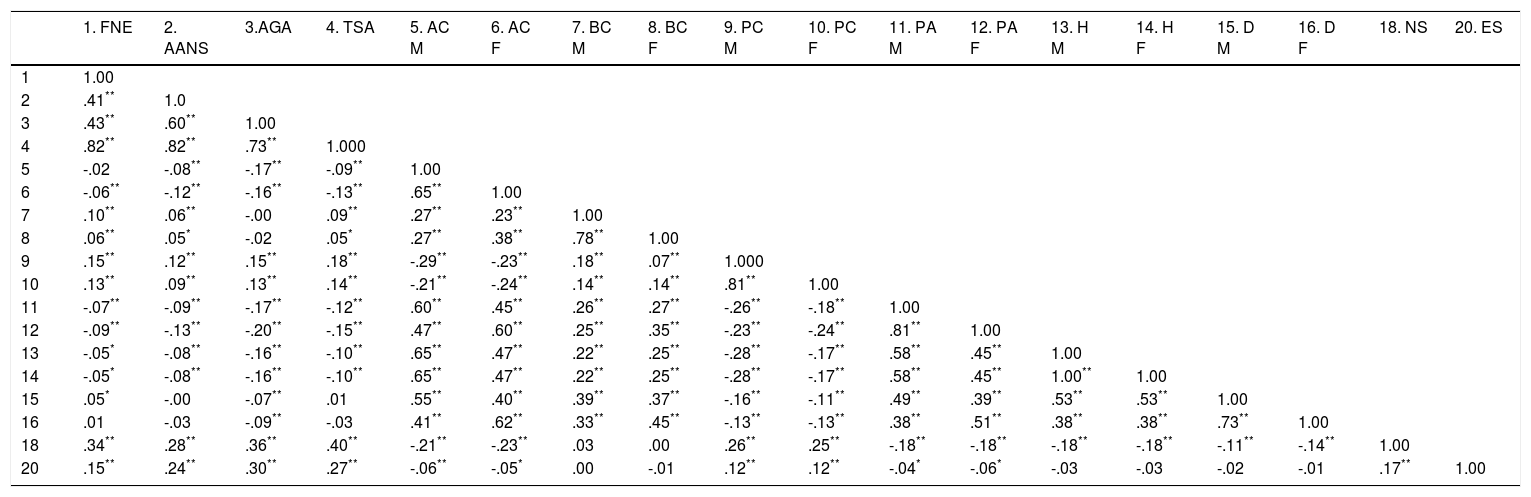

ResultsThe correlation analysis showed a negative relationship between affection and communication, the promotion of autonomy and humour and social anxiety. There was also a positive relationship between behavioural and psychological control and the responses given for social anxiety. On the other hand, a positive relationship was found between negative self-esteem and emotional suppression on the one hand, and social anxiety on the other. Negative self-esteem and emotional suppression were also linked positively to psychological control, and negatively to affection and communication and the promotion of autonomy. In addition, negative self-esteem was inversely related to parental humour and disclosure. There was a similar relationship between maternal and paternal educational practices and the rest of the variables. These results can be seen in Table 1.

Spearman correlation between the dimensions of social anxiety, parental educational practices, negative self-esteem and emotional suppression.

| 1. FNE | 2. AANS | 3.AGA | 4. TSA | 5. AC M | 6. AC F | 7. BC M | 8. BC F | 9. PC M | 10. PC F | 11. PA M | 12. PA F | 13. H M | 14. H F | 15. D M | 16. D F | 18. NS | 20. ES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | .41** | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | .43** | .60** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | .82** | .82** | .73** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | -.02 | -.08** | -.17** | -.09** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 6 | -.06** | -.12** | -.16** | -.13** | .65** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | .10** | .06** | -.00 | .09** | .27** | .23** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 8 | .06** | .05* | -.02 | .05* | .27** | .38** | .78** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 9 | .15** | .12** | .15** | .18** | -.29** | -.23** | .18** | .07** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 10 | .13** | .09** | .13** | .14** | -.21** | -.24** | .14** | .14** | .81** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 11 | -.07** | -.09** | -.17** | -.12** | .60** | .45** | .26** | .27** | -.26** | -.18** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 12 | -.09** | -.13** | -.20** | -.15** | .47** | .60** | .25** | .35** | -.23** | -.24** | .81** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 13 | -.05* | -.08** | -.16** | -.10** | .65** | .47** | .22** | .25** | -.28** | -.17** | .58** | .45** | 1.00 | |||||

| 14 | -.05* | -.08** | -.16** | -.10** | .65** | .47** | .22** | .25** | -.28** | -.17** | .58** | .45** | 1.00** | 1.00 | ||||

| 15 | .05* | -.00 | -.07** | .01 | .55** | .40** | .39** | .37** | -.16** | -.11** | .49** | .39** | .53** | .53** | 1.00 | |||

| 16 | .01 | -.03 | -.09** | -.03 | .41** | .62** | .33** | .45** | -.13** | -.13** | .38** | .51** | .38** | .38** | .73** | 1.00 | ||

| 18 | .34** | .28** | .36** | .40** | -.21** | -.23** | .03 | .00 | .26** | .25** | -.18** | -.18** | -.18** | -.18** | -.11** | -.14** | 1.00 | |

| 20 | .15** | .24** | .30** | .27** | -.06** | -.05* | .00 | -.01 | .12** | .12** | -.04* | -.06* | -.03 | -.03 | -.02 | -.01 | .17** | 1.00 |

Note. FNE=Fear of negative evaluation; AANS=Social avoidance and social anguish in new situations; AGA=Social avoidance and general anguish; TSA=Total social anxiety; AC=Affection and communication; BC=Behavioural control; PC=Psychological control; PA=Promotion of autonomy; H=Humour; D=Children Disclosure; M=Mother; F=Father; NS=Negative self-esteem; ES=Emotional suppression

To examine the direct relationship between parental educational practices and social anxiety, two independent SEMs were created, based on the maternal and paternal educational style. In both the maternal and parental model for educational practices, we found a significant, direct relationship between social anxiety and psychological control (βmother=.23; p <.05; βfather=.20; p <.05), affection and communication (βmother=-.15; p <.05; βfather=-.20; p <.05), humour (βmother=-.15; p <.05; βfather=-.21; p <.05), promotion of autonomy (βmother=-.14; p <.05; βfather=-.20; p <.05) and behavioural control (βmother=.12; p <.05; βfather=.08; p <.05). There was no significant relationship between disclosure to the mother and social anxiety, but there was in the case of the father (β=-.08; p <.05). Both models showed a good fit (mother: X2S-B=62775.27; G.L.=1643; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.014–.017); father: X2S-B=8417061.27; G.L.=1643; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.007–.017)). The direct effect of the parental dimensions accounted for 13.2% and 17.2% of the variance of social anxiety in the case of maternal and paternal educational practices, respectively.

To explore the indirect relationship between parental practices and social anxiety, mediated by negative self-esteem and emotional suppression, several independent SEMs were created according to the maternal and paternal educational style. First, we examined the direct relationship between negative self-esteem, emotional suppression and social anxiety. The model showed a good fit: X2S-B=3001.23; G.L.=294; p=.00; NNFI=.96; CFI=.97; RMSEA=.04 (IC:.042–.047), and both variables accounted for 44.1% of the variance in social anxiety. Both negative self-esteem (β=.54; p <.05) and emotional suppression (β=.37; p <.05) showed a significant positive relationship with the dependent variable.

Next, we examined the direct relationship between educational practices and negative self-esteem. Both the model for maternal educational practices (X2S-B=37145.49; G.L.=735; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.013–.018)) as well as the one based on paternal practices (X2S-B=37807.34; G.L.=523; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.010–.016)) showed a good fit. In both models, psychological control (βmother=.33; p <.05; βfather=.29; p <.05), affection and communication (βmother=-.25; p <.05; βfather=-.27; p <.05), humour (βmother=-.23; p <.05; βfather=-.30; p <.05) and the promotion of autonomy (βmother=-.22; p <.05; βfather=-.20; p <.05) showed a significant relationship with negative self-esteem. The maternal model accounted for 27.8% of the variance in negative self-esteem and the paternal model, 29.4%.

Thirdly, we evaluated the direct relationship between educational practices and emotional suppression. In both the mother's and the father's cases, only the dimension of psychological control showed a significant influence on emotional suppression (βmother=.18; p <.05; βfather=.14; p <.05). Both models showed a good fit (mother: X2S-B=31090.09; G.L.=735; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.010–.015); father: X2S-B=31353.36; G.L.=523; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.007–.014)), accounting for 3.5% of the variance in the maternal model and 2.7% in the paternal model.

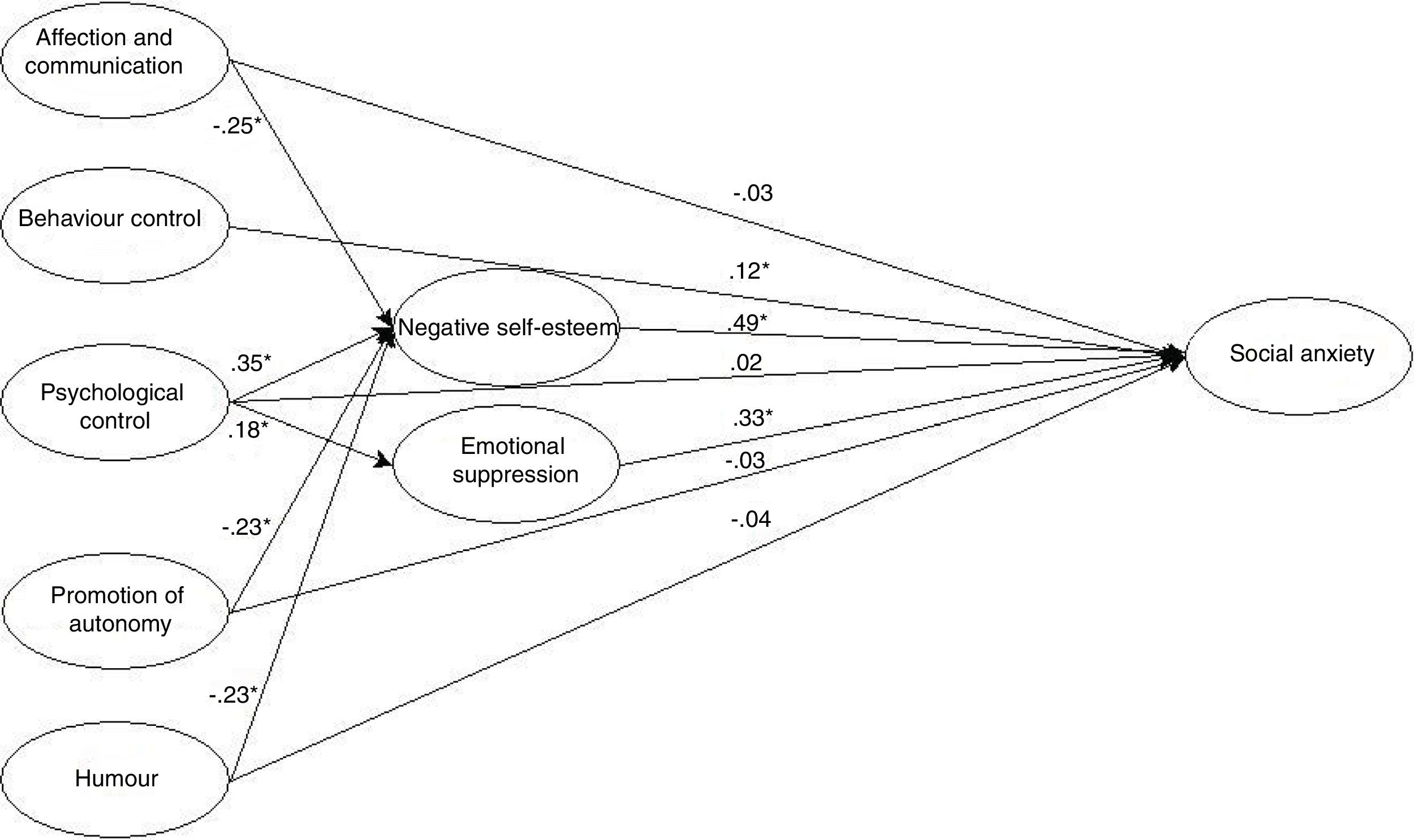

Based on the results obtained, we proposed a model which linked educational practices to social anxiety directly, but also indirectly, through their relationship with negative self-esteem and emotional suppression. The variables which were not found to be significant in the previous models were not included in the model.

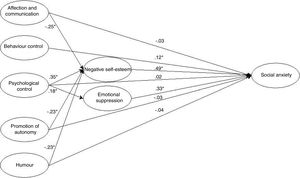

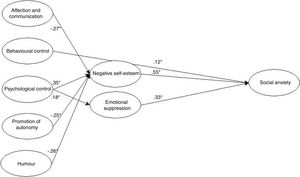

The maternal model (see Figure 1) showed a good fit: X2S-B=46467.2; G.L.=1814; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.011 (IC:.009–.013). Behavioural control showed a significant relationship with social anxiety (β=.12; p <.05). The rest of the parental practices did not show any significant direct effects. However, they were directly and significantly linked to negative self-esteem (βpsychologicalcontrol=.35; p <.05; βaffectionandcommunication=-.25; p <.05; βpromotionofautonomy=-.23; p <.05; βhumour=-.23; p <.05), accounting for 28.7% of its variance. Psychological control, the only dimension which was significant in the previous models, was directly and significantly linked to emotional suppression (β=.18; p <.05) accounting for 3.2% of the variance in this variable. Negative self-esteem (β=.49; p <.05) and emotional suppression (β=.33; p <.05) showed significant relationships with social anxiety. These effects accounted for 41.9% of the variance of the latter variable.

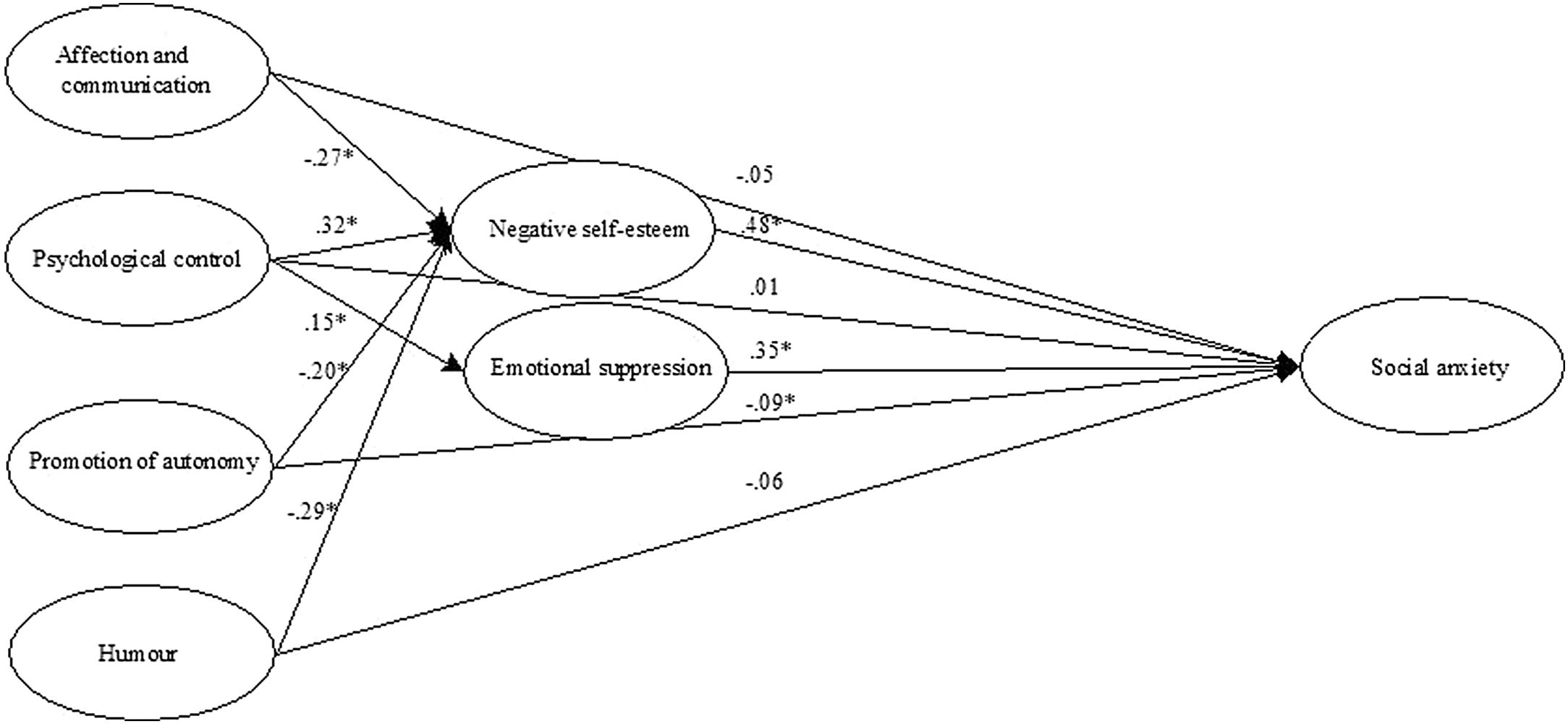

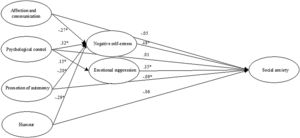

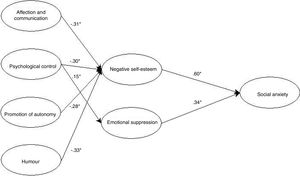

The paternal model (see Figure 2) also showed a good fit: X2S-B=50506.93; G.L.=1470; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.007–.012). Promotion of autonomy showed a significant relationship with social anxiety (β=-.09; p <.05). The other parental dimensions did not show any significant direct effects with social anxiety, but were directly and significantly linked to negative self-esteem (βpsychologicalcontrol=.32, p <.05; βhumour=-.29, p <.05; βaffectionandcommunication=-.27; p <.05; βpromotionofautonomy=-.20; p <.05), accounting for 30.3% of its variance. Psychological control was directly and significantly linked to emotional suppression (β=.15, p <.05), accounting for 2.4% of the variance. Negative self-esteem (β=.48; p <.05) and emotional suppression (β=.35; p <.05) showed significant relationships with social anxiety. These effects accounted for 43.5% of the variance in the latter variable.

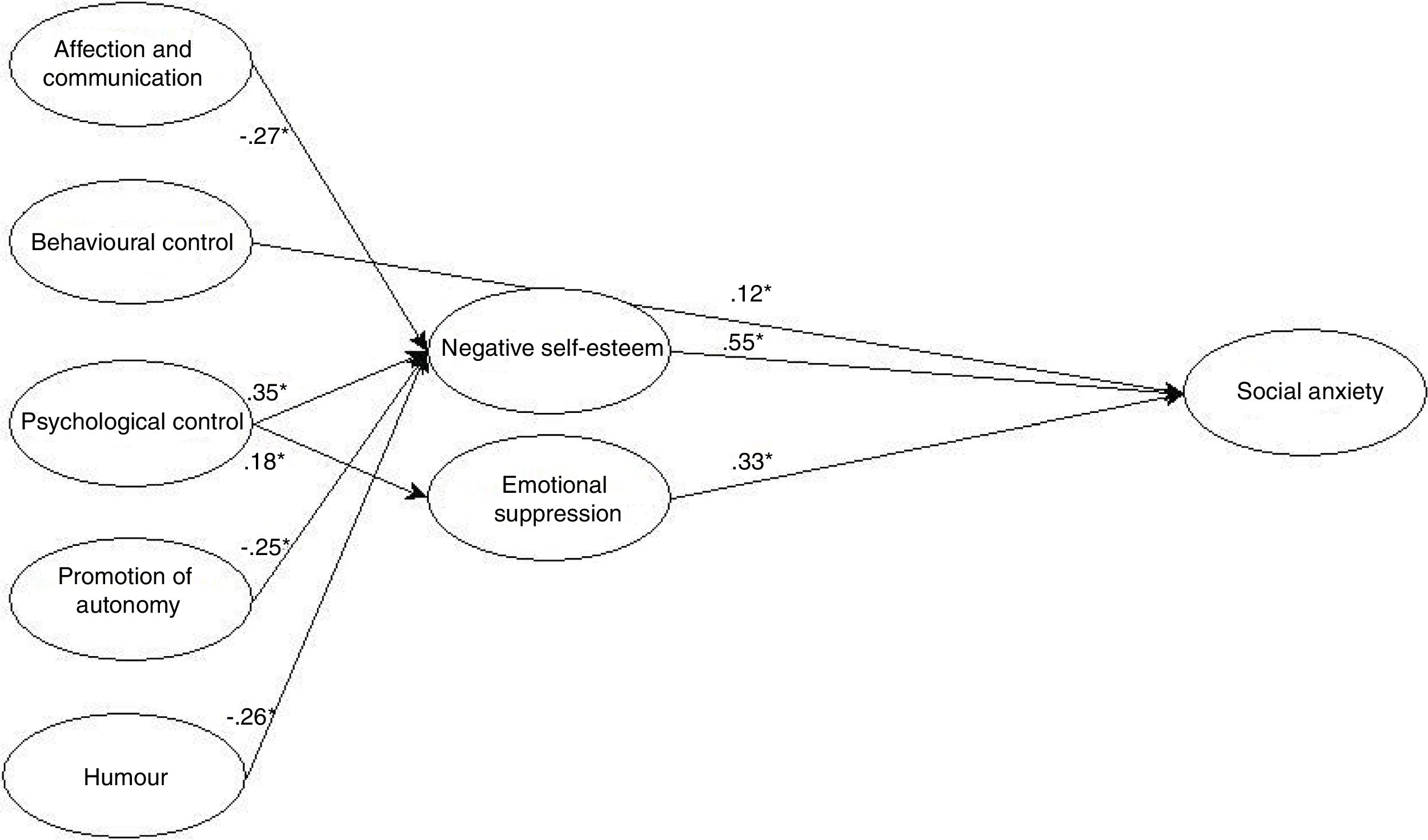

The definitive models were shaped by the relationships which were significant in the previous models, and a good adjustment was obtained. The maternal model (see Figure 3) showed a good fit: X2S-B=46044.16; G.L.=1818; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.01 (IC:.007–.012). The educational practice which showed a direct, significant relationship with social anxiety was behavioural control (β=.12; p <.05). The other parental dimensions were indirectly linked to social anxiety through their relationship with negative self-esteem (βpsychologicalcontrol=.35, p <.05; βaffectionandcommunication=-.27, p <.05; βhumour=-.26, p <.05, βpromotiondeautonomy=-.25, p <.05) and emotional suppression (βpsychologicalcontrol=.18, p <.05). These relationships accounted for 32.6% and 3.2% of the variance of negative self-esteem and emotional suppression, respectively. Both negative self-esteem (β=.55; p <.05) and emotional suppression (β=.33; p <.05) showed significant relationships with social anxiety. These effects accounted for 44.8% of the variance of social anxiety.

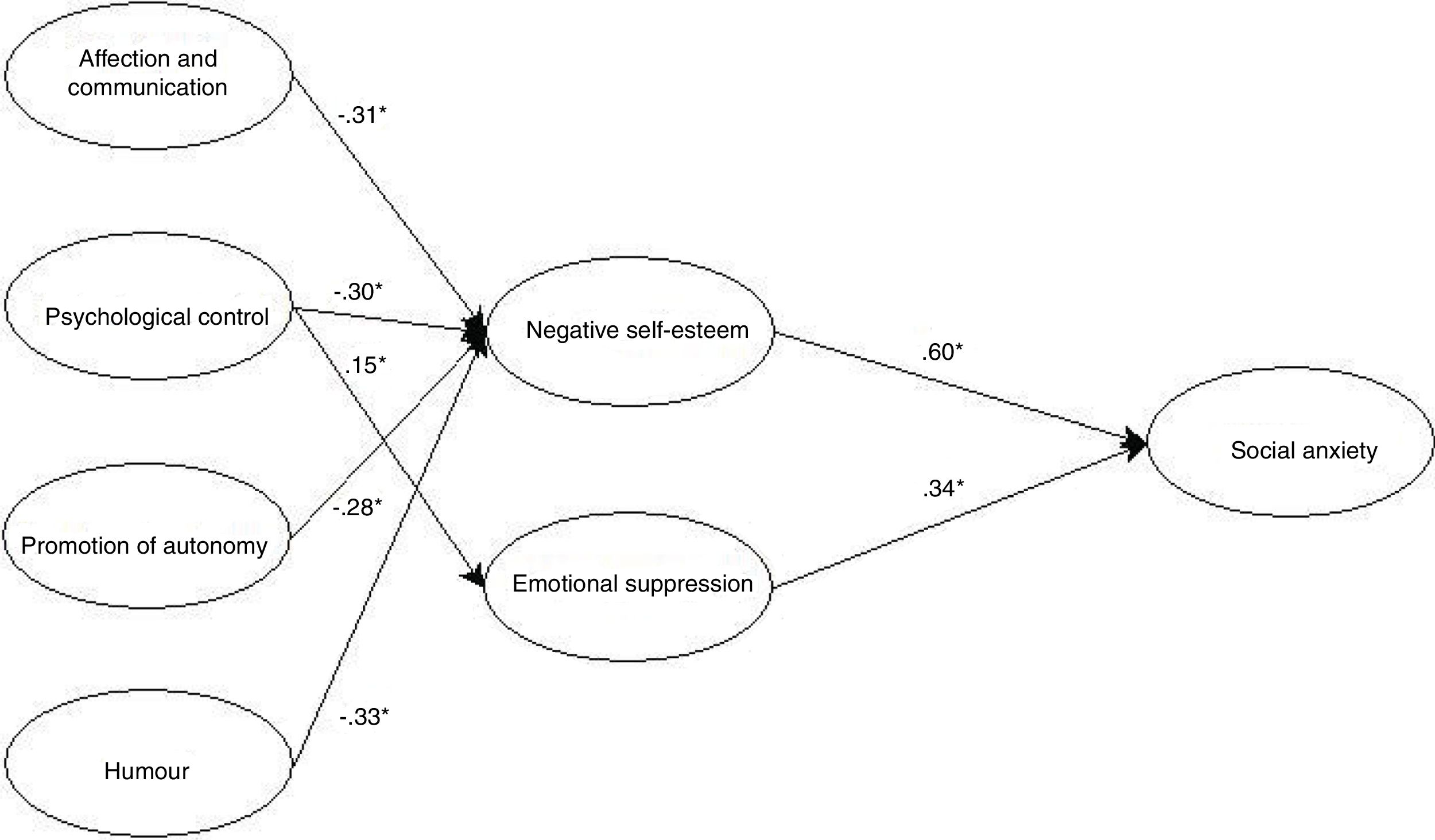

The paternal model (see Figure 4) which showed a good fit (X2S-B=50032.98; G.L.=18474; p=.00; NNFI=.99; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.008 (IC:.005–.011)), was the one made up of all the relationships of the previous model which were significant, except for the direct relationship between promotion of autonomy and social anxiety, which made the adjustment inappropriate and decreased the percentage of variance accounted for by social anxiety to 47.5%. In the final model, parental practices were indirectly linked to social anxiety through their relationship with negative self-esteem (βhumour=-.33, p <.05, βaffectionandcommunication=-.31; p <.05; βpsychologicalcontrol=.30; p <.05; βpromotiondeautonomy=-.28; p <.05;) and emotional suppression (β psychologicalcontrol=.15; p <.05). These relationships accounted for 37% and 2.1% of the variance in negative self-esteem and emotional suppression, respectively. Both negative self-esteem (β=.60; p <.05) and emotional suppression (β=.34; p <.05) showed significant relationships with social anxiety. These effects accounted for 49.1% of the variance in the latter variable.

DiscussionThis study has aimed to explore the direct and indirect relationships between maternal and paternal educational practices and adolescent social anxiety, assessing the mediating influence of individual factors such as negative self-esteem and emotional suppression. The results confirm a direct relationship between maternal and paternal educational practices and social anxiety, albeit with a low effect size, as we predicted in the hypothesis, which was also in line with previous evidence (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2016; Knappe et al., 2012). We noted that in both parents, the dimension of psychological control was the variable which had the highest relationship coefficient with social anxiety. This appears to suggest that, although the other parental dimensions may contribute to the development of social anxiety, the problem is mainly linked to the low self-esteem and insecurity which arises when the parents employ intrusive and manipulative procedures, which rather than serving simply as a means of parental control over the child, end up forcing them give in and lose their identity (Barber & Xia, 2013).

The results of the models confirmed the second hypothesis, which predicted an indirect relationship between parental practices and social anxiety, mediated by negative self-esteem and emotional suppression. The lack of affection and communication, the limited promotion of autonomy, a lack of humour and psychological control are the parental practices which seem to contribute most towards social anxiety in young people, stimulating the perception of low self-esteem and encouraging the use of ineffective emotional regulation strategies, such as emotional suppression. These results are in line with those of previous studies, which have already demonstrated the mediating role of self-esteem and emotional regulation between the educational style and infant-juvenile adjustment (Bozicevic et al., 2016; Wouters et al., 2018).

The mediating variable which showed the closest relationship with social anxiety was negative self-esteem, rather than emotional suppression. This relationship is consistent with the results of other studies which also highlight the prominent role played by self-esteem in the development of this problem, compared to other variables (Caballo et al., 2018; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2018). This result seems to indicate that the problem of social anxiety, despite being closely linked to the emotional world (Jazaieri et al., 2015; Kivity & Huppert, 2018), is mainly a problem of self-confidence, in which the individual constantly questions their own worth, leading to the cognitive interferences which are so characteristic of this problem and which seem to form the cornerstone it is built on: the fear of negative evaluation (American Psychiatric Association, 2014; Van Tuijl et al., 2014).

Contrary to our hypothesis, the results of this study did not reveal major differences in the relative influence of each educational practice on social anxiety, but they did attach greater importance to parental practices in accounting for this problem. Further research into the differentiated influence of both parents in the development of social anxiety during adolescence would be needed to enable us to draw any clear conclusions about it.

To sum up, the results of this research show that, despite the growing importance of other contexts, the family continues to be a fundamental reference point during adolescence. It constitutes a context which helps the child socialize and develop, and its key tools are the educational style adopted by the parents and the practices and attitudes displayed within it (Oliva et al., 2007). Parents must therefore provide a source of affection, while promoting communication, a healthy degree of autonomy and a warm, positive rapport within the family. These practices must be accompanied by a necessary degree of supervision, but this should not entail the use of manipulative and intrusive strategies, whose effect has been shown to be extremely harmful. This will encourage the child to internalize their feeling of worth and help them to manage their emotions by resorting to effective procedures, rather than simply suppressing unpleasant emotions, which, in turn, may contribute to the prevention of problems such as social anxiety.

This study has several limitations. It uses a cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to establish the causal relationships between parental educational practices and social anxiety. Another limitation is the use of the adolescent as the sole source of information, thus providing only one point of view in what is essentially a dyadic relationship. Despite this, some studies show that the adolescent's viewpoint tends to be more objective than that of their parents, who tend to be more biased by the influence of social desirability (Oliva et al., 2007). On the other hand, it is also a limitation to use a single test to evaluate a phenomenon as complex as social anxiety, although this test is widely used in many different languages and cultures. To confirm the causality of the model, future longitudinal research would be required to reveal the temporal relationship between parental practices, the mediating variables and social anxiety, and, as a result, to clarify the real influence of these factors on this social phenomenon.

FundingThis work is part of the following projects funded by the Spanish Government (R & D Plan): PSI2016-74871-R and PSI2015-64114-R; it is also part of the H2020 project, which is funded by the European Research Council: 755175.