Background/Objective: Most studies have evaluated victimization at a single time point, making it difficult to determine the impact of the time during which an individual is victimized. This longitudinal study aims to examine the differences in the levels of social status (social preference and perceived popularity) and friendship in peer victimization trajectories, and to analyse if there were changes over time in the levels of social status and friendship in each trajectory. Method: The final sample was composed of 1,239 students (49% girls) with ages between 9 and 18 (M = 12.23, SD = 1.73), from 22 schools in southern Spain. Peer nominations were collected. Results: The General Linear Model results associated the highest levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship with the sporadic victimization profile and the lowest levels of these dimensions with the stable profile. Conclusions:The results are discussed based on important personal aspects of stable victimization that confirms social rejection, unpopularity, and the low social support that victimization causes. This contribution is discussed in terms of health and social welfare in adolescence.

Antecedentes/Objetivo:La mayoría de los estudios han evaluado la victimización en un único momento temporal, lo que impide determinar el impacto del tiempo durante el que un individuo es victimizado. Este estudio longitudinal pretende examinar las diferencias en los niveles de estatus social (preferencia social y popularidad percibida) y amistad entre las diferentes trayectorias de las víctimas de iguales en función de su trayectoria de victimización, y explorar si existen cambios con el paso del tiempo en los niveles de estatus social y amistad de cada trayectoria. Método:La muestra se compuso por 1.239 estudiantes (49% chicas) entre 9 y 18 años (M = 12,23, DT = 1,73), pertenecientes a 22 centros educativos del sur de España. Se utilizaron las hetero-nominaciones de sus iguales dentro del grupo de clase. Resultados:Los resultados del Modelo Lineal General asociaron los niveles más altos de preferencia social, popularidad percibida y amistad a la victimización esporádica, y los niveles más bajos de estas dimensiones a la trayectoria estable. Conclusiones:Los resultados se discuten en base al rechazo social, la impopularidad y los escasos apoyos sociales que provoca la victimización. Se valora esta aportación a nivel de salud y bienestar social adolescente.

Bullying in schools is the occurrence of interpersonal violence among peers which is produced and sustained inside the group, and in which one or more aggressors display different types of behaviour which harm the victim physically, psychologically and morally. It does not refer to a one-off act of aggression, but rather to an intentional process sustained over a period of time (Smith, 2016). Many schoolchildren who are victims of intimidation, abuse or bullying manage to shake off this oppression and, although they may suffer temporarily, are not necessarily aware of having suffered victimization. Others, however, are so hurt by the experience that they feel victimized and suffer somatic conditions (Rey, Neto, & Extremera, 2020). These feelings lead the victim to believe that their aggressor is more powerful and socially dominant than them, thus distorting the accepted social balance between peers which should mark them, by their status, as equals (Ortega-Ruiz, 2020).

Around 36% of schoolchildren are bullied by their peers, according to the meta-analysis carried out with 80 studies from different countries (Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, 2014), and the percentage of severe cases ranges from 3 to 10% (Elgar et al., 2015). Over recent years, there has been a growing number of longitudinal studies which have explored the time period during which an individual has been bullied. In addition, the study by Zych et al. (2020) points out that the majority of the schoolchildren who are victims are trapped in the same role. A growing body of research has begun to explore through longitudinal designs the differences between chronic victims, who are exposed to sustained bullying over a long period of time, and those who are bullied for a limited time (Ouellet-Morin et al., 2020; Sheppard, Giletta, & Prinstein, 2019). According to these studies, chronic victims have higher levels of chronic stress, as well as externalizing and internalizing personality problems, which are not found in schoolchildren who are unaware bullying is taking place or who have suffered from bullying in a shorter or less traumatic way (Haltigan & Vaillancourt, 2014; Rosen, Beron, & Underwood, 2017; Sukhawathanakul & Leadbeater, 2020; Sumter, Baumgartner, Valkenburg, & Peter, 2012).

For a variety of reasons, the harassing behaviour of bullying affects the personal and social development of both victims and aggressors alike (Garcia-Hermoso, Oriol-Granado, Correa-Bautista, & Ramírez-Vélez, 2019), but it also impacts the social dynamics of the group/class (Romera, Bravo, Ortega-Ruiz, & Veenstra, 2019; Salmivalli, 2010). When this type of behaviour is tolerated by a group/class, the victimization processes are acknowledged by all the members of the group, who identify them with the unjustified, immoral acts of aggression known as bullying. Thus, when bullying is widely recognized in a peer group, the phenomenon of victimization and its effects are just as noticeable (Isaacs, Hodges, & Salmivalli, 2008; Pouwels, Lansu, & Cillessen, 2016; van der Ploeg, Steglich, Salmivalli, & Veenstra, 2015). Research which has explored the relationship between bullying and problems with peers has shown that victimization predicts problems of social adjustment among peers (see meta-analysis by Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010) and vice versa (see review by Prinstein & Giletta, 2016). In the recent meta-analysis by Casper, Card, and Barlow (2020), victimization associates negatively with acceptance and friendship, and positively with rejection among schoolchildren. Nevertheless, most longitudinal studies on victimization have measured social adjustment at a single point in time, which makes it difficult to measure how the variability of the levels of adjustment over time is associated with the degree of victimization. The aim of this study was to explore social adjustment, in terms of social status and friendship, associated with different patterns of victimization among peers in the pre-adolescent and adolescent stages, where very few studies of chronic victimization have been conducted. This research has particular relevance at this developmental stage, in which the relationships of friendship, acceptance and visibility within the peer group begin to play a more important role and the children are more vulnerable to bullying from other schoolchildren (Lam, Law, Chan, Wong, & Zhang, 2014; Romera, Herrera-López, Casas, Ortega-Ruiz, & Gómez-Ortiz, 2017).

In previous research, social status has been described as the social position an individual occupies within a group, which encompasses two dimensions: social preference and popularity (Saarento, Boulton, & Salmivalli, 2015). Social preference is a measure of affect and refers to maintaining a warm, friendly relationship with other group members (Pouwels et al., 2016; Pouwels, Salmivalli, Saarenyo, van den Berg, & Cillessen, 2018). Popularity, on the other hand, refers to a relative social position which involves visibility and social prestige, It is a hierarchical concept, in that occupying a prominent position relegates other members of the group to a lower position (Lafontana & Cillessen, 2010). Both social characteristics have been linked to schoolchildren’s behaviour, especially perceived popularity, which starts to play a key role during adolescence (Lafontana & Cillessen, 2010; Reijntjes et al., 2018).

As regards the occurrence of bullying, the research shows that victims of bullying tend to be unpopular and are rarely accepted by their peers (Isaacs et al., 2008; Pouwels et al., 2018). The study by Pouwels et al. (2018) argues that the social characteristics of unpopularity and rejection usually appear before bullying takes place. Other studies have shown that victimization is linked to a negative perception of others, which increases the victim's social distance from the group (Ladd, Ettekal, Kochenderfer‐Ladd, Rudolph, & Andrews, 2014; Romera et al., 2016Romera, Gómez-Ortiz, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016). It follows, therefore, that those who perceive the victim to be characterless and dull will not go out of their way to defend them against bullying (van den Berg, Burk, & Cillessen, 2015).

The longitudinal study by Sheppard et al. (2019) showed how victims evolve according to their social preference and perceived popularity, in four different categories: those who experience chronic, decreasing, increasing or low-stable levels of victimization. This longitudinal study, with 3 annual time points, showed that, at the third time point, chronic victims were less likely to be rated by their peers on indices of likeability and popularity. However, it did not look into how the social status levels of the different types of victims can also vary over time, which is the object of this research.

The few studies conducted which deal with friendship and victimization in adolescence stress that having friends, as well as the nature and quality of those friendships, can act as a protection factor against victimization, reducing the risk of getting involved in bullying and alleviating its consequences (Salmivalli, 2018). Although friendship can protect adolescents from victimization, most victims often have fewer friends than their non-victimized peers. Longitudinal studies on friendship and victimization show that schoolchildren without friends who are victimized are more likely to continue being victimized over time (Light, Rusby, Nies, & Snijders, 2014) and, in turn, that victimized adolescents who establish bonds of friendship are more likely to escape from this situation (Rosen et al., 2017). We need, then, to explore how friendship levels interact over time with changes in the evolution of victimization, in order to provide vital clues about how to prevent and take action in cases of bullying.

Given that time is an important factor in the phenomenon of bullying, there is a marked lack of longitudinal studies which deal with the victimization process. The present study has two main objectives: (1) to explore whether differences exist over time in each trajectory of victimization in levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship; and (2) to describe any time-based differences between the different trajectories of victimization in levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship. The following hypotheses were proposed: (1) the levels of social preference, popularity and friendship will be stable in sporadic and chronic victims; and (2) chronic victims will have the lowest levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship over time.

MethodParticipantsThree longitudinal cohorts were studied in order to observe the trajectories of victimization, and the students were classified according to the stability of their role. The first cohort consisted of 318 students from 5th year of Primary School (at T1 and T2), who by the time of T3 were mostly in 6th year of Primary School (3.60% repeated the course). The second cohort was made up of 514 students in 1 st year of Secondary school in T1 and T2, most of whom were in 2nd year of Secondary school by the time of T3 (8.30% repeaters). Finally, the third cohort was made up of 514 students who were in 3rd year of Secondary school in T1 and T2, most of whom were in 4th year of Secondary school by the time of T3 (10.10% of repeaters).

Of the total number of 1,346 students who took part, we excluded for whom any of the following conditions were true: students who abandoned the research at any time (change of school) or had started at the school at any time after the first year; also, students who at any of the three evaluation stages belonged to classes that had less than 80% of the sociometric data of the class group. In total, 107 students (7.20%) were removed. The final sample was made up of 1,239 schoolchildren (49% girls) aged between 9 and 18 years (M = 12.23, DT = 1.73), who belonged to 22 schools in the province of Córdoba, in southern Spain (12 of these were Secondary Schools, nine Primary and one which had both educational stages).

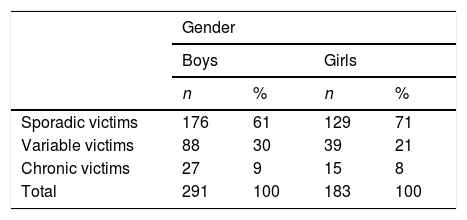

Of the total number of schoolchildren who took part, 477 (38.80%) were identified by their peers as having been victims at some time. Three of these were excluded as information about their gender was missing. The final sample consisted of 474 students, of whom 305 (64.40%) were categorized as sporadic victims, 127 (26.80%) as variable victims and 42 (8.80%) as chronic victims (Table 1). No differences were observed in the prevalence levels of these trajectories, either by gender or by school year (χ2 = 5.24, p = .073; χ2 = 6.03, p = .197, respectively).

Description by gender and school year of the trajectories of victimization.

| Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sporadic victims | 176 | 61 | 129 | 71 |

| Variable victims | 88 | 30 | 39 | 21 |

| Chronic victims | 27 | 9 | 15 | 8 |

| Total | 291 | 100 | 183 | 100 |

| School year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th year Primary | 1st year Secondary | 3rd year Secondary | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sporadic victims | 95 | 62 | 122 | 69 | 90 | 61 |

| Variable victims | 40 | 26 | 45 | 26 | 43 | 29 |

| Chronic victims | 18 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 15 | 10 |

| Total | 153 | 100 | 176 | 100 | 148 | 100 |

All data were collected using peer nomination, which is considered the most valid and reliable way of measuring social status and social behaviour within the peer group (Coie & Dodge, 1983).

Social preference, perceived popularity and friendship. The variables of friendship, social preference and perceived popularity were explored through five sociometric questions: (a) for perceived popularity: which children are popular? (positive popularity) and who is unpopular? (negative popularity); (b) for social preference: who do you like? (degree of acceptance) and who do you dislike? (degree of rejection); and (c) for friendship: who are your friends in class?

Victimization. The levels of victimization for each schoolchild were established based on the answers given by the classmates to the sociometric question: who are victims in your class? It had been explained to them previously that the definition of ‘a victim of their peers’ was someone who had been intentionally and repeatedly assaulted physically, verbally, psychologically or socially by their male or female schoolmates. Different examples were given of the way each of these kinds of behaviour was manifested.

They were told that the class was the reference group and each participant could select as many of their peers as they wished. They were not allowed to choose themselves or include terms such as “nearly everyone” or “hardly anyone”. The nominations made by each schoolchild were recorded and the data was standardized by class. The levels of social preference (levels of acceptance minus levels of rejection) and perceived popularity (levels of popularity minus levels of unpopularity) of each participant were calculated.

The ‘allocation to victimization’ variable was calculated for each time period, with two categories created within the variable: schoolchildren with a score above their class mean (z > 0) plus a deviation (z > .10) were assigned to the ‘victims’ category and the others to the ‘non-victims’ category. Schoolchildren who had been identified as victims were categorized as follows: those who were identified in a single time period were categorized as sporadic victims (and were assigned a value of 1); those who had been victims in 2 of the 3 time periods were categorized as variable victims (value: 2); and those who had been victims in all 3 time periods were categorized as stable victims (value: 3). Schoolchildren categorized as ‘non-victims’ were excluded from the present study, as in previous research (Rosen et al., 2017; Sheppard et al., 2019).

ProcedureIntentional non-probability sampling was used, for greater accessibility. The school management was informed about the aims of the research. The regional government authorized the research to be conducted in those schools which had shown interest in taking part. In addition, the families of the minors were asked for their signed consent to participate (which approximately 2% did not give). It was stressed that participation was entirely on a voluntary and anonymous basis. Data collection was carried out during school hours in one-hour sessions. In order to guarantee anonymity, the participants were required to nominate their peers using numbers on a list prepared by the class tutor. The data was collected at three time points, which spanned two school years. The first two were collected in the 2017-2018 academic year (T1: October; and T2: May) and the third during in the 2018-2019 academic year (T3: October). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the University of Córdoba Ethics Committee.

Data analysisThe statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS v.25 program. Transversal covariance analysis models (ANCOVA) were created separately to explore the possible effect of the trajectories of victimization on levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship in the three time periods measured, taking gender and school year as covariates. A General Linear Model (GLM) was created for each dependent variable (social preference, perceived popularity and friendship), with the different groups of the trajectories of victimization (sporadic, variable and chronic) as the variable between subject and time (three measuring times) as an intra-subject variable. The effect of time (as a longitudinal dimension) was examined, as was time by type of victimization trajectory (interaction effect). Gender and school year were included as covariates to avoid possible effects as confounding factors.

All post-hoc tests were subjected to the Bonferroni correction. Significance levels of p < .05 were accepted in all analyses.

ResultsThe results of the ANCOVA models showed significant differences in the levels of social preference (T1: F(2, 469) = 25.80, p < .001; T2: F(2, 469) = 28.68, p < .001; T3: F(2, 469) = 24.63, p < .001), perceived popularity (T1: F(2, 469) = 19.50, p < .001; T2: F(2, 469) = 21.59, p < .001; T3: F(2, 469) = 15.46, p < .001) and friendship (T1: F(2, 469) = 16.22, p < .001;T2: F(2, 469) = 16.42, p < .001; T3: F(2, 469) = 17.25, p < .001) for the different victimization trajectories at the three time points measured, and no differences in these levels of significance were found after controlling for the effects of gender and school year on each model. The results showed a significant effect of gender on the social preference variable at time point 2 (F(1, 469) = 28.11, p = .005) and on that of friendship at time points 2 and 3 (F(1, 469) = 5.59, p = 0,018; F(1, 469) = 4.04, p = .045, respectively).

Longitudinal differences in social preference, perceived popularity, and friendship in trajectories of victimizationTo find an answer to the first main objective of this study, we considered the intra-subject results of the three GLMs. No significant interaction was observed between trajectories of victimization (sporadic, variable and chronic) and time in the levels of social preference (F(4, 938) = 1.01, p = .398), perceived popularity (F(4, 938) = 1.13, p = .398), and friendship (F(4, 938) = 0.11, p = .978). The only significant relationship found was between gender and time in levels of social preference (F(2, 468) = 3.37, p = .035).

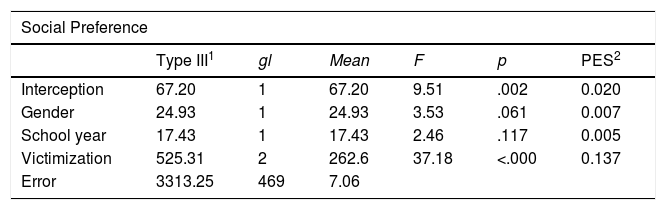

Longitudinal differences in social preference, perceived popularity, and friendship between the types of victimization trajectoriesTo answer the second of the study objectives, the inter-subject results of the three GLMs were considered. Differences were observed in the estimated mean scores for social preference (F(2, 469) = 37.18, p < .001), perceived popularity (F(2, 469) = 22.07, p < .001) and friendship (F(2, 469) = 24.91, p < .001) among the types of victimization trajectories (Table 2).

GLM test effects between subjects on the estimated levels of social preference, popularity and friendship in the trajectories of victimization.

| Social Preference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III1 | gl | Mean | F | p | PES2 | |

| Interception | 67.20 | 1 | 67.20 | 9.51 | .002 | 0.020 |

| Gender | 24.93 | 1 | 24.93 | 3.53 | .061 | 0.007 |

| School year | 17.43 | 1 | 17.43 | 2.46 | .117 | 0.005 |

| Victimization | 525.31 | 2 | 262.6 | 37.18 | <.000 | 0.137 |

| Error | 3313.25 | 469 | 7.06 | |||

| Perceived Popularity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III1 | gl | Mean | F | p | PES2 | |

| Interception | 24.70 | 1 | 24.70 | 2.92 | .088 | 0.006 |

| Gender | 23.65 | 1 | 23.65 | 8.80 | .095 | 0.006 |

| School year | 5.56 | 1 | 5.56 | 0.65 | .418 | 0.001 |

| Victimization | 372.60 | 2 | 186.30 | 22.07 | <.001 | 0.086 |

| Error | 3958.37 | 469 | 8.44 | |||

| Friendship | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type III1 | gl | Mean | F | p | PES2 | |

| Interception | 1.89 | 1 | 1.89 | 0.30 | .299 | 0.002 |

| Gender | 11.73 | 1 | 11.73 | 6.70 | .010 | 0.014 |

| School year | 0.56 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.32 | .571 | 0.001 |

| Victimization | 87.26 | 2 | 43.63 | 24.91 | <.001 | 0.096 |

| Error | 821.41 | 469 | 1.75 | |||

Note.1Sum of squares. 2 Partial eta square.

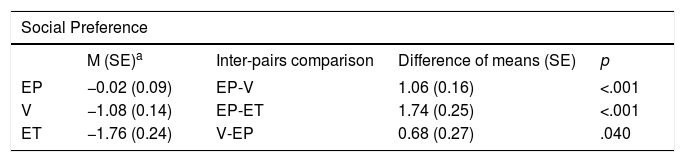

In particular, the post hoc tests showed, firstly, significant differences in the mean scores for social preference between all types of victimization trajectories; secondly, that schoolchildren with sporadic victimization trajectories had a higher estimated mean popularity score than students belonging to the other two trajectories (variable and stable); and thirdly, significant differences in the mean friendship scores between the three types of victimization trajectory. See Table 3.

Comparison of levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship between the different trajectories of victimization.

| Social Preference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE)a | Inter-pairs comparison | Difference of means (SE) | p | |

| EP | −0.02 (0.09) | EP-V | 1.06 (0.16) | <.001 |

| V | −1.08 (0.14) | EP-ET | 1.74 (0.25) | <.001 |

| ET | −1.76 (0.24) | V-EP | 0.68 (0.27) | .040 |

| Perceived Popularity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE)a | Inter-pairs comparison | Difference of means (SE) | p | |

| EP | 0.65 (0.10) | EP-V | 0.83 (0.18) | <.001 |

| V | −0.77 (0.15) | EP-ET | 1.54 (0.28) | <.001 |

| ET | −1.48 (0.26) | V-EP | 0.71 (0.30) | .053 |

| Friendship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE)a | Inter-pairs comparison | Difference of means (SE) | p | |

| EP | 0.03 (0.04) | EP-V | 0.41 (0.09) | <.001 |

| V | −0.38 (0.07) | EP-ET | 0.74 (0.13) | <.001 |

| ET | −0.71 (0.12) | V-EP | 0.33 (0.14) | .048 |

Note. EP: Sporadic; V: Variable; ET: Stable. a Based on estimated marginal means. Covariates of the model are evaluated at the following values: gender = 1.39, school year = 2.90.

Finally, the only significant relationship found was between the covariate of gender and the estimated mean levels of friendship (Table 2).

DiscussionThe idea behind this study was to explore the variability over time of the levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship in the different trajectories of victimization. The results showed that 38,80% of the participants had been victimized in one of the three study time periods. This prevalence is similar to the 36% found in the meta-analysis carried out in 80 studies from different countries by Modecki et al. (2014). Similarly, the prevalence of chronic victims (8,80%) was within the 3-10% range found by Elgar et al. (2015).

The first hypothesis of the study was confirmed by the General Linear Model, with the levels of social preference, popularity and friendship remaining stable over time in sporadic and chronic victims, but also in variable victims (a trajectory whose stability had not been hypothesized). These results emphasise the important role of social study variables in understanding the phenomenon of victimization, as they reveal the type of relationships schoolchildren have with their peers (Casper, Card, & Barlow, 2020). However, they also emphasize the social configuration of class groups, where schoolchildren assume roles and positions in the social hierarchy. These roles tend to remain fixed for a certain time and make it difficult for victims to break free from this destructive pattern of dominance and submission established within the peer network, a fact which could explain how victimization is prolonged over time.

These results support the idea that a key tactic when intervening in situations of bullying could be to try to break down certain harmful social structures in the classroom (Rambaran, van Duijn, Dijkstra, & Veenstra, 2019). The results observed for gender show the relevance of controlling the effect of this variable in these analyses. Indeed, schoolchildren’s gender seems to have a greater effect on aspects related to more affective and trust-based social interactions, such as friendship, and a lesser effect on variables based on status and hierarchical organization, such as popularity.

As for the second hypothesis, the results confirmed that chronic victims maintained the lowest levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship over time, which concurs with previous cross-sectional (Pouwels et al., 2016) and longitudinal studies (Sheppard et al., 2019; Sukhawathanakul & Leadbeater, 2020). The low levels of social status and friendship experienced by chronic victims highlight the situation of rejection and isolation to which they are subjected by their classmates as a group. This relational dynamic does not vary or change, but rather remains stable, as do the consequences associated with it (Pouwels et al., 2018; Romera, Casas, Gómez-Ortiz, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2019). Although the victim’s perception of harm already produces consequences for them, the results of this study point out that as victimization becomes chronic, levels of social adjustment, in all three categories, tend to decrease. This may be due to the fact that being deprived of opportunities to share positive experiences with others is associated with the development of dysfunctional styles of social interaction which could become fixed, producing negative feedback and making the situation chronic (Pouwels et al., 2018). Indeed, previous studies have shown how, as victimization stabilizes, schoolchildren suffer worse physical, psychological, social, and emotional consequences (Isaacs et al., 2008; van der Ploeg et al., 2015). Furthermore, the social situation which chronic victims find themselves in also makes it difficult for them to break free of victimization by themselves; while, on the other hand, maintaining quality friendships can act as a protection factor against it (Salmivalli, 2018).

Up to now, studies on the trajectories of victimization have explored their relationship with popularity and social preference (Sheppard et al., 2019). This is therefore the first study to show how this relation remains stable over the three time points recorded. The very low levels of social preference, perceived popularity and friendship received by chronic victims are especially alarming, as these levels are far below those obtained by sporadic and variable victims. These results suggest that the stabilization of victimization has highly negative social repercussions for schoolchildren, and prevention and intervention measures are required to alleviate not only the effects associated with victimization, but also the conditioning factors of the peer network which reinforces the practice of subjecting certain boys and girls to isolation and rejection from their peers. The fact that our study included a large number of participants and was able to follow the evolution of the variables over time has enabled us to draw conclusions which can be adjusted to the social reality in schools, in terms of bullying and relationships among peers during the transition to adolescence, which is such a crucial moment in their development.

However, this work also has its limitations. Our study takes into account only peer nominations within the class group, which, while avoiding social desirability bias, only takes the views of some of the informants into consideration. Future research should also take into account the perception of all their peers and should explore the victims’ social adjustment through self-reports. Similarly, it would be of great interest to include in the analysis of the victimization process not only the frequency and duration, but also the intensity, a variable which could help in the configuration of the schoolchildren’s psychological and social adjustment. At the methodological level, the classification of the trajectories would be optimal from a latent analysis of classes, although the classification criterion used here, based on the number of times in that time period when an individual was victimised, corresponds to previous research (Bogart et al., 2014; Bowes et al., 2013). Future studies should explore the characteristics within the micro-groups of a single class, which would help to give us a more adjusted view of the social reality experienced in the classroom.

This research aims to raise awareness among the entire educational community, especially teachers, about the vital role they have to play in preventing the rejection and avoidance behaviour suffered by victims, as well as their responsibility for encouraging and helping to manage relationships among the peer group. Schools are widely accepted as the main setting where most relationships between peers are established and they are therefore the ideal place to prevent and alleviate bullying. The results of this study emphasise that fostering a friendly climate of coexistence in the classroom and the school, as well as encouraging the development of key competences to prevent this problem, such as social, moral and emotional competence, should be key aspects in any prevention program. Not only should coexistence in the classroom and the school should be managed democratically, but programs should also be focused on educating emotions, morality and values (Sorrentino & Farrington, 2019). This should be carried out using resources which foster dialogue, conflict resolution, cooperation and the assertive expression of the children’s own opinions, as a positive way of managing interpersonal relationships.

FundingThis study was funded by the Government of Spain, R+D+i, Ministry of Science and Innovation (PSI2016-74871-R).