Background/Objective: This study explored the association between active school travel (AST) and suicide attempts among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Method: We used the data from the Global School-based Health Survey, including 127,097 adolescents aged 13-17 years from 34 LMICs. A self-reported survey was used to collect data on AST and suicide attempts as well as some variables. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess the association between AST and suicide attempts. A meta-analysis with random effects was undertaken to identify the difference in the association between AST and suicide attempts. Results: Across all the adolescents, the prevalence of AST was 37% and the prevalence of suicide attempts was 11.60%. Adolescents who engaged in AST were less likely to have suicide attempts irrespective of gender. The country-wise analysis indicated a large inconsistency in the association between AST and suicide attempt across the countries. Conclusions: AST would appear to be a protective factor for reducing suicide attempts among adolescents. However, the association between AST and suicide attempts varied greatly across the countries. Future studies should confirm the association between AST and suicide attempts.

Objetivo: Se exploró la asociación entre desplazamientos escolares activos (AST, por sus siglas en inglés) e intentos de suicidio entre adolescentes en países de ingresos bajos y medios. Método: Se utilizaron datos de la Global School-based Health Survey, que incluyó a 127.097 adolescentes de 13 a 17 años de 34 países de ingresos bajos y medios. Se utilizó una encuesta autoinformada para recopilar datos sobre AST e intentos de suicidio, así como otras variables. Se realizó una regresión logística multivariable para evaluar la asociación entre AST e intentos de suicidio. Se realizó un metanálisis con efectos aleatorios para identificar la diferencia en la asociación entre AST e intentos de suicidio. Resultados: La prevalencia de AST fue del 37% y la prevalencia de intentos de suicidio fue del 11,60%. Los adolescentes que participaron en AST tenían menos probabilidades de tener intentos de suicidio independientemente del sexo. El análisis por países indicó una gran inconsistencia en la asociación entre AST e intento de suicidio. Conclusiones: AST parece ser un factor protector para reducir los intentos de suicidio entre adolescentes. Sin embargo, la asociación entre AST e intentos de suicidio varió mucho entre países. Estudios futuros deberían confirmar la asociación entre AST e intentos de suicidio.

Suicide among school-aged children and adolescents represents the second biggest contributor to global mortality, with more than 200,000 deaths recorded (World Health Organization, 2019). Approximately 80% of suicidal cases among adolescents occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; Organization World Health, 2019). Notably, a history of previous suicide attempts represents one of the strongest predictors of further suicide attempts and completed suicide, and this association has been previously reported in some studies that included young populations (Bostwick, Pabbati, Geske, & McKean, 2016). Therefore, identifying potentially modifiable risk factors (e.g., behavioral, social, and psychological) to reduce suicide attempts among adolescents is a public health priority, particularly in LMICs (Geng et al., 2020; Jacob, Stubbs, Firth et al., 2020; Jacob, Stubbs, & Koyanagi, 2020; Lew et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; von Brachel et al., 2019).

A large body of data, collated over previous decades, has demonstrated well-established associations between lifestyle factors (e.g., physical activity [PA], sedentary behavior, and sexual behavior) and suicide attempts (Felez-Nobrega et al., 2020; Jacob, Stubbs, Firth et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Vancampfort et al., 2019). Some studies have focused on the role of PA in preventing suicide attempts, with one meta-analysis indicating that active participation in PA can be a protective factor against suicide attempts among adolescents (Vancampfort, Hallgren et al., 2018). For example, a US study with an adolescent sample (N = 13,583) found that students who reported exercising 4 to 5 days per week had significantly lower odds of suicide attempts than those who exercised 0 to 1 day per week (Sibold et al., 2015). In addition, Felez-Nobrega et al. (2020) reported that a higher level of habitual PA was less likely to be associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.70-0.86) in boys, but not girls. Conversely, some studies have indicated that PA does not have any protective effect on suicide attempts among adolescents. For example, a large-scale US study (N = 65,182 middle-school students) found no association between overall PA levels and suicide attempts (Southerland et al., 2016). Chinese researchers also reported similar findings and concluded that increased PA might not be a protective factor against suicide attempts (Tao et al., 2007). Counter-intuitively, one study reported that frequent high-intensity PA might be associated with an increased odds for suicide attempts among Korean adolescents (Lee et al., 2013). These differing results might due to the type of PA engaged or respective contexts. Against this background, it is urgently needed explore the clear associations between some specific types of PA and suicide attempts among adolescents. Explorations of this research issue would be valued because the evidence can provide more practical implications and effective strategies for suicide preventions. Furthermore, considering the complexity of PA, identifying its components with positive roles in reducing suicide attempts is critically valuable.

Active school travel (AST; i.e., walking or riding bicycles between home and school), is an important component of PA that commonly occurred in daily life, particularly among adolescents (Aubert et al., 2018; Tremblay et al., 2016). It is well-known that AST is associated with numerous physical health benefits among youths such as improvements in, or maintenance of, body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness (Lubans, Boreham, Kelly, & Foster, 2011; Schoeppe, Duncan, Badland, Oliver, & Curtis, 2013). Recently, both Eastern and Western researchers have started to investigate the association of AST with mental health outcome, suggesting that children and adolescents engaging in AST have lower odds of developing mental problems like depression (Gu & Chen, 2020; Sun et al., 2015). Because of the potential psychological benefits resultant from AST (Edward et al., 2017), especially in reducing depression which is one of the key predictors of suicide attempts (Klonsky et al., 2016), it is conceivable that AST could be an effective approach in regulating such predictors (e.g., depression, anxiety, and loneliness) that are closely associated with greater odds of suicide attempts among children and adolescents (Aubert et al., 2018; Koyanagi et al., 2019; Pengpid & Peltzer, 2019; Sharma et al., 2015), leading to a reduced probability of committing suicide. However, little research has directly established association between AST and suicide attempts among school-based children and adolescents who experience multifaceted pressures including academic stress and problems in interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, there is an absence of multi-country and LMIC research investigating associations between AST and suicide attempts. Owing to the rising number of suicides in LMICs in recent years (Nunez-Gonzalez et al., 2018), more feasible ways to prevent adolescent suicide attempts is needed.

Indeed, if the veracity of the association between AST and suicide attempts can be demonstrated, more effective and efficient interventions, for preventing suicide could be implemented. Therefore, given the dearth of research, the present study investigated the relationship between AST and suicide attempts by using data from 34 LMICs from the World Health Organization regions.

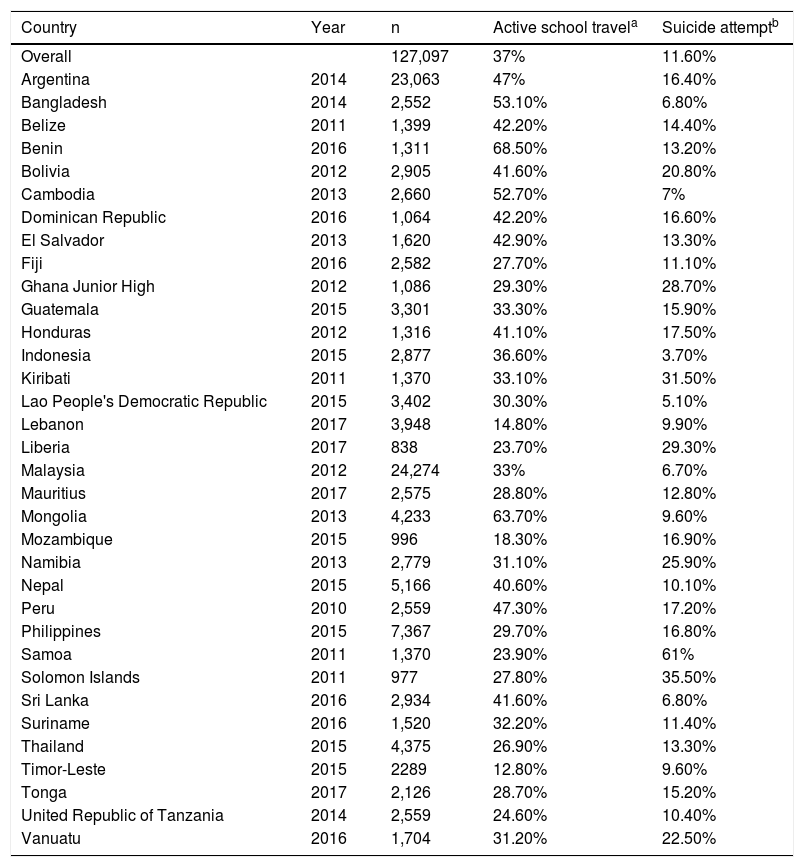

MethodParticipantsPublicly available data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) were analyzed in this study. Details on this survey can be found at http://www.who.int/chp/gshs and http://www.cdc.gov/gshs, respectively. Briefly, the GSHS was jointly developed by the World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other United Nations allies. The core aim of the survey was to assess and quantify risk and protective factors of major non-communicable diseases. The survey used a standardized two-stage probability sampling design for the selection process within each participating country. For the first stage, schools were selected with probability proportional to size sampling. The second stage involved the random selection of classrooms that included students, within each selected school. All students in the selected classrooms were eligible to participate in the survey, and data collection was performed during one regular class period. The questionnaire was translated into the local language in each country and consisted of multiple-choice response options. Students recorded their responses on computer scannable sheets. All GSHS surveys were approved, in each country, by both a national government administration (most often the Ministry of Health or Education) and an institutional review board or ethics committee. Student privacy was protected through anonymous and voluntary participation, and informed consent was obtained, as appropriate, from the students, parents, and/or school officials. Data were weighted for non-response and probability selection. From all the publicly available data, we selected all datasets that included the variables pertinent to our analysis. If there were more than two datasets from the same country during this period, we chose the most recent dataset. A total of 34 countries were included in the current study, and, based on the World Bank classification at the time of the survey, all countries were classed as LMICs. Data were nationally representative for all countries, with the exception of some countries. The characteristics of each country, including the sample size and the response rate are provided in Table 1.

Sample characteristics by each country included in this study.

| Country | Year | n | Active school travela | Suicide attemptb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 127,097 | 37% | 11.60% | |

| Argentina | 2014 | 23,063 | 47% | 16.40% |

| Bangladesh | 2014 | 2,552 | 53.10% | 6.80% |

| Belize | 2011 | 1,399 | 42.20% | 14.40% |

| Benin | 2016 | 1,311 | 68.50% | 13.20% |

| Bolivia | 2012 | 2,905 | 41.60% | 20.80% |

| Cambodia | 2013 | 2,660 | 52.70% | 7% |

| Dominican Republic | 2016 | 1,064 | 42.20% | 16.60% |

| El Salvador | 2013 | 1,620 | 42.90% | 13.30% |

| Fiji | 2016 | 2,582 | 27.70% | 11.10% |

| Ghana Junior High | 2012 | 1,086 | 29.30% | 28.70% |

| Guatemala | 2015 | 3,301 | 33.30% | 15.90% |

| Honduras | 2012 | 1,316 | 41.10% | 17.50% |

| Indonesia | 2015 | 2,877 | 36.60% | 3.70% |

| Kiribati | 2011 | 1,370 | 33.10% | 31.50% |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 2015 | 3,402 | 30.30% | 5.10% |

| Lebanon | 2017 | 3,948 | 14.80% | 9.90% |

| Liberia | 2017 | 838 | 23.70% | 29.30% |

| Malaysia | 2012 | 24,274 | 33% | 6.70% |

| Mauritius | 2017 | 2,575 | 28.80% | 12.80% |

| Mongolia | 2013 | 4,233 | 63.70% | 9.60% |

| Mozambique | 2015 | 996 | 18.30% | 16.90% |

| Namibia | 2013 | 2,779 | 31.10% | 25.90% |

| Nepal | 2015 | 5,166 | 40.60% | 10.10% |

| Peru | 2010 | 2,559 | 47.30% | 17.20% |

| Philippines | 2015 | 7,367 | 29.70% | 16.80% |

| Samoa | 2011 | 1,370 | 23.90% | 61% |

| Solomon Islands | 2011 | 977 | 27.80% | 35.50% |

| Sri Lanka | 2016 | 2,934 | 41.60% | 6.80% |

| Suriname | 2016 | 1,520 | 32.20% | 11.40% |

| Thailand | 2015 | 4,375 | 26.90% | 13.30% |

| Timor-Leste | 2015 | 2289 | 12.80% | 9.60% |

| Tonga | 2017 | 2,126 | 28.70% | 15.20% |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2014 | 2,559 | 24.60% | 10.40% |

| Vanuatu | 2016 | 1,704 | 31.20% | 22.50% |

Notes. a Having walked or cycled to school at least 5 days per week. b Having at least one suicide attempt during the past 12 months.

Active school travel was assessed by a single question: “How many days did you walk or ride a bicycle to and from school during the past 7 days?”. Participants self-reported their responses according to their actual situations (responses: 0–7 days, as integers). Participants having 5 days or more for walking or cycling were regarded as being active, whereas those not reporting 5 days or more for walking or cycling were regarded as being passive. The rationale for selecting 5 days or more, is that adolescents across different countries normally have a minimum of 5 days for schooling per week, which is in line with our previous (as yet unpublished) studies.

Suicide attempts were assessed by the question “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” , and was defined as at least one suicide attempt in the past 12 months, which is in line with previous research (Felez-Nobrega et al., 2020).

Gender, age, physical activity, sedentary behavior, presence of close friends, anxiety-induced insomnia, fruit and vegetable intake, fast food consumption, and alcohol consumption, as well as food insecurity, were used as control variables in the analysis, based on previous studies. To assess levels of physical activity, questions that represented the PACE + Adolescent Physical Activity Measure were asked, which has been shown to be reliable and valid Questions were asked to ascertain the number of days where at least 60 minutes of physical activity during the past 7 days, not including physical activity during physical education or gym classes, was achieved (Prochaska et al., 2001). Sedentary behavior was assessed with the question “How much time do you spend during a typical or usual day sitting and watching television, playing computer games, talking with friends, or doing other sitting activities?” with answer options: < 1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, or ≥ 8 h/day. The presence of close friends was defined as having at least one close friend. Anxiety-induced insomnia was assessed with the question: “During the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?” with answer options: ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘most of the time’, and ‘always’. Those who answered ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’ were considered to have anxiety-induced insomnia.

As in previous research using the GSHS datasets (Felez-Nobrega et al., 2020; Prochaska et al., 2001; Vancampfort, Stubbs et al., 2018), food insecurity was treated as a proxy for socioeconomic status as no variables on socioeconomic status were included in the GSHS datasets. Food insecurity was assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, how often did you go hungry because there was not enough food in your home?” Answer options were in five categories: “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time” and “always”.

Statistical analysesAll statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.6.1, 2019). Descriptive analysis was used to calculate the prevalence of AST (defined as occurring at least 5 days a week) and suicide attempt (defined as at least once over the past 12 months). The prevalence of AST and suicide attempts by country were also calculated. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was utilized to assess the association between AST and suicide attempts (overall, by gender and country). The variables of AST and suicide attempt were treated as binary. The regression analysis was adjusted for gender, age, food insecurity, presence of close friends, anxiety-induced insomnia, fruit and vegetable intake, fast food consumption, alcohol consumption, physical activity and sedentary behavior, as well as country, with the exception of the gender-stratified and country-wise analyses which were not adjusted for gender and country, respectively. To assess the level of between-country heterogeneity, the Higgin’s I2 statistic was calculated based on country-wise estimates. This represents the degree of heterogeneity that is not explained by sampling error with a value of < 40% often considered as negligible, and 40–60% as moderate heterogeneity (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). A pooled estimate was obtained by combining the estimates for each country into a random effect meta-analysis. All variables were included in the regression analyses as categorical variables, with the exception of age and PA which were treated as continuous variables. Less than 3.80% of the data were missing for all the variables used in the analysis. Complete case analysis was conducted, and Taylor linearization methods were used in all analyses to account for the sample weighting and complex study design. Results from the logistic regression analyses are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the statistical significance level was set at p < .05, a priori.

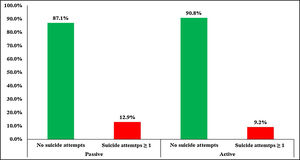

ResultsThe final sample included 127,097 adolescents aged 13-17 years (mean age = 14.60 years, SD = 1.20; 52% male). The sample of each country ranged from 838 (Liberia) to 24,274 (Malaysia) as provided in Table 1. Overall, the prevalence of AST and suicide attempts was 37% (5 or more days for walking or biking) and 11.60% (having at least one suicide attempt), respectively. The prevalence rates varied greatly across the included countries: AST: 12.80% (Timor-Leste) to 68.50% (Benin), suicide attempts: 3.70% (Indonesia) to 61% (Samoa).

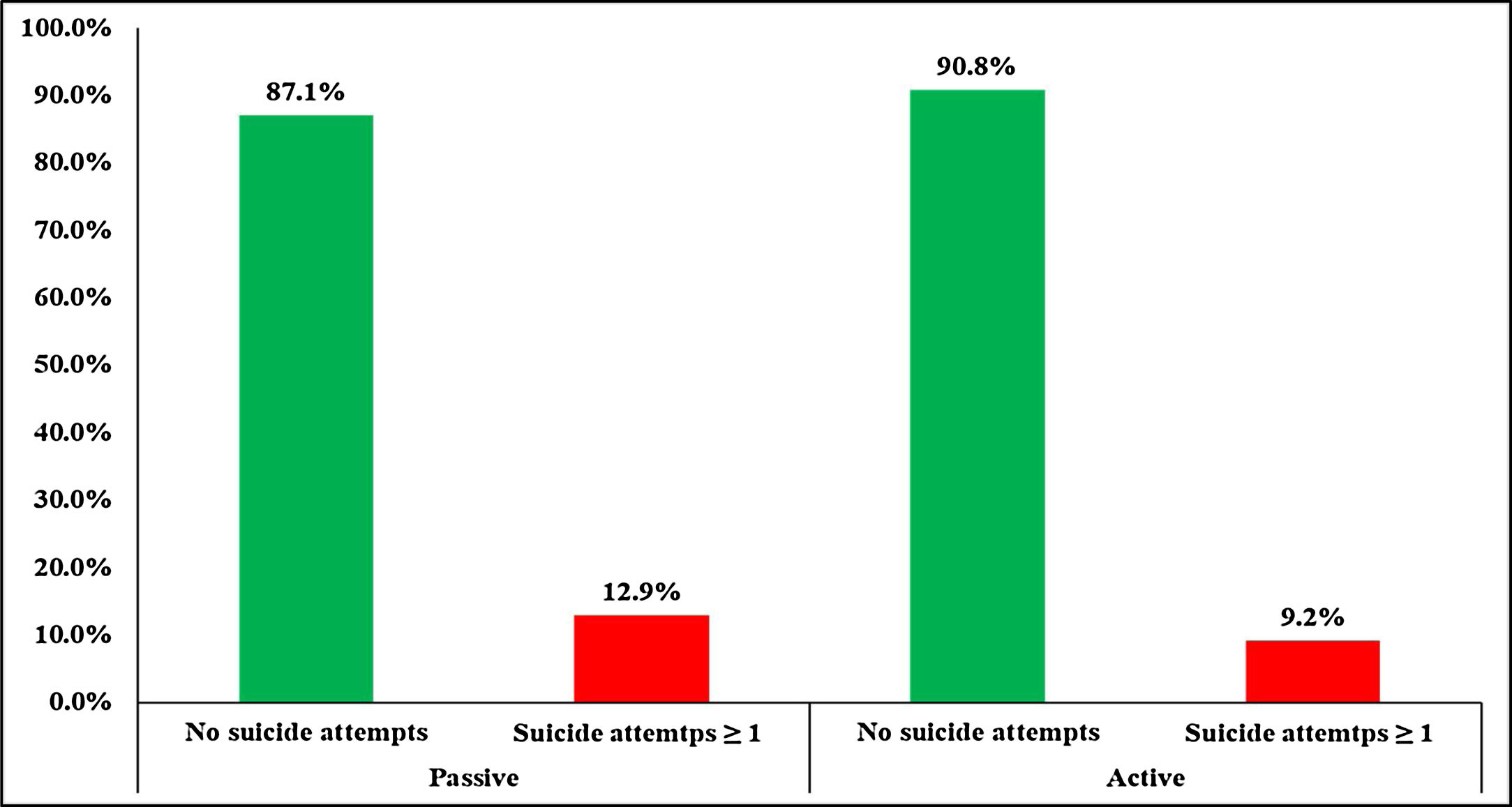

Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of suicide attempts by being active and passive in school travel, respectively. Specifically, in the samples with AST, the prevalence of having at least 1 suicide attempt was 9.20%, which was lower than passive in school travel counterparts (12.90%).

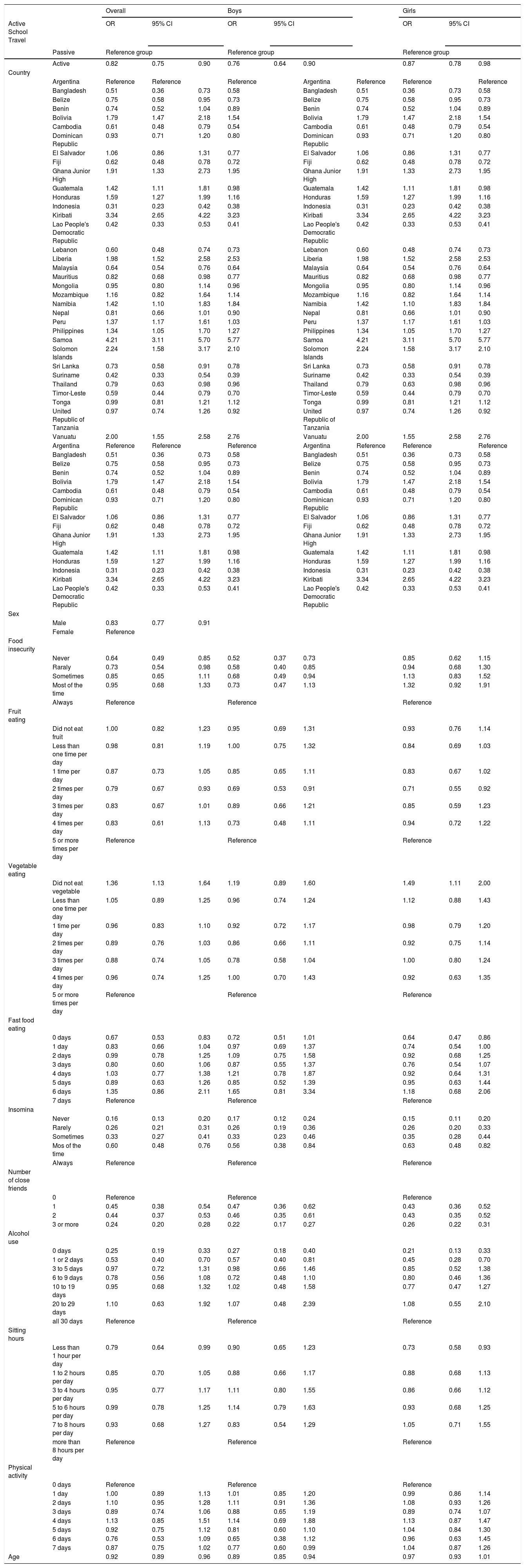

Table 2 details the association between AST and suicide attempts in the samples. In the fully adjusted model, adolescents with AST were less likely to attempt suicide (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.75-0.90, p < .001). Among boys, those who had AST also had a lower odds ratio for suicide attempts (OR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.64-0.90, p < .005). A similarly significant relationship was also observed in girls (OR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.78-0.98, p < .05). More information on the associations between other variables and suicide attempts can be found in Table 2.

Association between active school travel and suicide attempts over the past 12 months estimated by multivariable logistic regression (by overall and gender).

| Overall | Boys | Girls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active School Travel | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Passive | Reference group | Reference group | Reference group | ||||||||

| Active | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.98 | ||

| Country | |||||||||||

| Argentina | Reference | Reference | Reference | Argentina | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Bangladesh | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.58 | Bangladesh | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.58 | ||

| Belize | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 0.73 | Belize | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 0.73 | ||

| Benin | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.04 | 0.89 | Benin | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.04 | 0.89 | ||

| Bolivia | 1.79 | 1.47 | 2.18 | 1.54 | Bolivia | 1.79 | 1.47 | 2.18 | 1.54 | ||

| Cambodia | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.54 | Cambodia | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.54 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 0.80 | Dominican Republic | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 0.80 | ||

| El Salvador | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.77 | El Salvador | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.77 | ||

| Fiji | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.72 | Fiji | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.72 | ||

| Ghana Junior High | 1.91 | 1.33 | 2.73 | 1.95 | Ghana Junior High | 1.91 | 1.33 | 2.73 | 1.95 | ||

| Guatemala | 1.42 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 0.98 | Guatemala | 1.42 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 0.98 | ||

| Honduras | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.99 | 1.16 | Honduras | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.99 | 1.16 | ||

| Indonesia | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.38 | Indonesia | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.38 | ||

| Kiribati | 3.34 | 2.65 | 4.22 | 3.23 | Kiribati | 3.34 | 2.65 | 4.22 | 3.23 | ||

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.41 | Lao People's Democratic Republic | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.41 | ||

| Lebanon | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.74 | 0.73 | Lebanon | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.74 | 0.73 | ||

| Liberia | 1.98 | 1.52 | 2.58 | 2.53 | Liberia | 1.98 | 1.52 | 2.58 | 2.53 | ||

| Malaysia | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.64 | Malaysia | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.64 | ||

| Mauritius | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.77 | Mauritius | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.77 | ||

| Mongolia | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.14 | 0.96 | Mongolia | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.14 | 0.96 | ||

| Mozambique | 1.16 | 0.82 | 1.64 | 1.14 | Mozambique | 1.16 | 0.82 | 1.64 | 1.14 | ||

| Namibia | 1.42 | 1.10 | 1.83 | 1.84 | Namibia | 1.42 | 1.10 | 1.83 | 1.84 | ||

| Nepal | 0.81 | 0.66 | 1.01 | 0.90 | Nepal | 0.81 | 0.66 | 1.01 | 0.90 | ||

| Peru | 1.37 | 1.17 | 1.61 | 1.03 | Peru | 1.37 | 1.17 | 1.61 | 1.03 | ||

| Philippines | 1.34 | 1.05 | 1.70 | 1.27 | Philippines | 1.34 | 1.05 | 1.70 | 1.27 | ||

| Samoa | 4.21 | 3.11 | 5.70 | 5.77 | Samoa | 4.21 | 3.11 | 5.70 | 5.77 | ||

| Solomon Islands | 2.24 | 1.58 | 3.17 | 2.10 | Solomon Islands | 2.24 | 1.58 | 3.17 | 2.10 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.78 | Sri Lanka | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.78 | ||

| Suriname | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.39 | Suriname | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.39 | ||

| Thailand | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.96 | Thailand | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.96 | ||

| Timor-Leste | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.79 | 0.70 | Timor-Leste | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.79 | 0.70 | ||

| Tonga | 0.99 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 1.12 | Tonga | 0.99 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 1.12 | ||

| United Republic of Tanzania | 0.97 | 0.74 | 1.26 | 0.92 | United Republic of Tanzania | 0.97 | 0.74 | 1.26 | 0.92 | ||

| Vanuatu | 2.00 | 1.55 | 2.58 | 2.76 | Vanuatu | 2.00 | 1.55 | 2.58 | 2.76 | ||

| Argentina | Reference | Reference | Reference | Argentina | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Bangladesh | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.58 | Bangladesh | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.58 | ||

| Belize | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 0.73 | Belize | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 0.73 | ||

| Benin | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.04 | 0.89 | Benin | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.04 | 0.89 | ||

| Bolivia | 1.79 | 1.47 | 2.18 | 1.54 | Bolivia | 1.79 | 1.47 | 2.18 | 1.54 | ||

| Cambodia | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.54 | Cambodia | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.54 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 0.80 | Dominican Republic | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.20 | 0.80 | ||

| El Salvador | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.77 | El Salvador | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.31 | 0.77 | ||

| Fiji | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.72 | Fiji | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.72 | ||

| Ghana Junior High | 1.91 | 1.33 | 2.73 | 1.95 | Ghana Junior High | 1.91 | 1.33 | 2.73 | 1.95 | ||

| Guatemala | 1.42 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 0.98 | Guatemala | 1.42 | 1.11 | 1.81 | 0.98 | ||

| Honduras | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.99 | 1.16 | Honduras | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.99 | 1.16 | ||

| Indonesia | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.38 | Indonesia | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.38 | ||

| Kiribati | 3.34 | 2.65 | 4.22 | 3.23 | Kiribati | 3.34 | 2.65 | 4.22 | 3.23 | ||

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.41 | Lao People's Democratic Republic | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.41 | ||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.91 | ||||||||

| Female | Reference | ||||||||||

| Food insecurity | |||||||||||

| Never | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 1.15 | ||

| Raraly | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 1.30 | ||

| Sometimes | 0.85 | 0.65 | 1.11 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.94 | 1.13 | 0.83 | 1.52 | ||

| Most of the time | 0.95 | 0.68 | 1.33 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 1.13 | 1.32 | 0.92 | 1.91 | ||

| Always | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Fruit eating | |||||||||||

| Did not eat fruit | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.23 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 1.31 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 1.14 | ||

| Less than one time per day | 0.98 | 0.81 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.32 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 1.03 | ||

| 1 time per day | 0.87 | 0.73 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.02 | ||

| 2 times per day | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.92 | ||

| 3 times per day | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 1.21 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 1.23 | ||

| 4 times per day | 0.83 | 0.61 | 1.13 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 1.22 | ||

| 5 or more times per day | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Vegetable eating | |||||||||||

| Did not eat vegetable | 1.36 | 1.13 | 1.64 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 1.60 | 1.49 | 1.11 | 2.00 | ||

| Less than one time per day | 1.05 | 0.89 | 1.25 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.24 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 1.43 | ||

| 1 time per day | 0.96 | 0.83 | 1.10 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 1.20 | ||

| 2 times per day | 0.89 | 0.76 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.14 | ||

| 3 times per day | 0.88 | 0.74 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.24 | ||

| 4 times per day | 0.96 | 0.74 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 1.43 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.35 | ||

| 5 or more times per day | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Fast food eating | |||||||||||

| 0 days | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.01 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.86 | ||

| 1 day | 0.83 | 0.66 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 1.37 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 days | 0.99 | 0.78 | 1.25 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 1.58 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 1.25 | ||

| 3 days | 0.80 | 0.60 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.55 | 1.37 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 1.07 | ||

| 4 days | 1.03 | 0.77 | 1.38 | 1.21 | 0.78 | 1.87 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 1.31 | ||

| 5 days | 0.89 | 0.63 | 1.26 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 1.39 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 1.44 | ||

| 6 days | 1.35 | 0.86 | 2.11 | 1.65 | 0.81 | 3.34 | 1.18 | 0.68 | 2.06 | ||

| 7 days | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Insomina | |||||||||||

| Never | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.20 | ||

| Rarely | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.33 | ||

| Sometimes | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.44 | ||

| Mos of the time | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.82 | ||

| Always | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Number of close friends | |||||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.52 | ||

| 2 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.52 | ||

| 3 or more | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.31 | ||

| Alcohol use | |||||||||||

| 0 days | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.33 | ||

| 1 or 2 days | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.81 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.70 | ||

| 3 to 5 days | 0.97 | 0.72 | 1.31 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 1.38 | ||

| 6 to 9 days | 0.78 | 0.56 | 1.08 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 1.10 | 0.80 | 0.46 | 1.36 | ||

| 10 to 19 days | 0.95 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 1.02 | 0.48 | 1.58 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 1.27 | ||

| 20 to 29 days | 1.10 | 0.63 | 1.92 | 1.07 | 0.48 | 2.39 | 1.08 | 0.55 | 2.10 | ||

| all 30 days | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Sitting hours | |||||||||||

| Less than 1 hour per day | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.23 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.93 | ||

| 1 to 2 hours per day | 0.85 | 0.70 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 1.17 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 1.13 | ||

| 3 to 4 hours per day | 0.95 | 0.77 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 0.80 | 1.55 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 1.12 | ||

| 5 to 6 hours per day | 0.99 | 0.78 | 1.25 | 1.14 | 0.79 | 1.63 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 1.25 | ||

| 7 to 8 hours per day | 0.93 | 0.68 | 1.27 | 0.83 | 0.54 | 1.29 | 1.05 | 0.71 | 1.55 | ||

| more than 8 hours per day | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Physical activity | |||||||||||

| 0 days | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| 1 day | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 1.14 | ||

| 2 days | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 1.11 | 0.91 | 1.36 | 1.08 | 0.93 | 1.26 | ||

| 3 days | 0.89 | 0.74 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 1.07 | ||

| 4 days | 1.13 | 0.85 | 1.51 | 1.14 | 0.69 | 1.88 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.47 | ||

| 5 days | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.12 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.30 | ||

| 6 days | 0.76 | 0.53 | 1.09 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 1.12 | 0.96 | 0.63 | 1.45 | ||

| 7 days | 0.87 | 0.75 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 1.26 | ||

| Age | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 | ||

Notes. a Denotes controlling for country, gender, age, food insecurity, presence of close friends, anxiety-induced insomnia, fruit and vegetable intake, fast food consumption, alcohol consumption, physical activity and sedentary behavior. b Denotes controlling for country, age, food insecurity, presence of close friends, anxiety-induced insomnia, fruit and vegetable intake, fast food consumption, alcohol consumption, physical activity and sedentary behavior. c Denotes reporting at least 5 days of active school travel per week. ** p < .05, ** p < .005, *** p < .001.

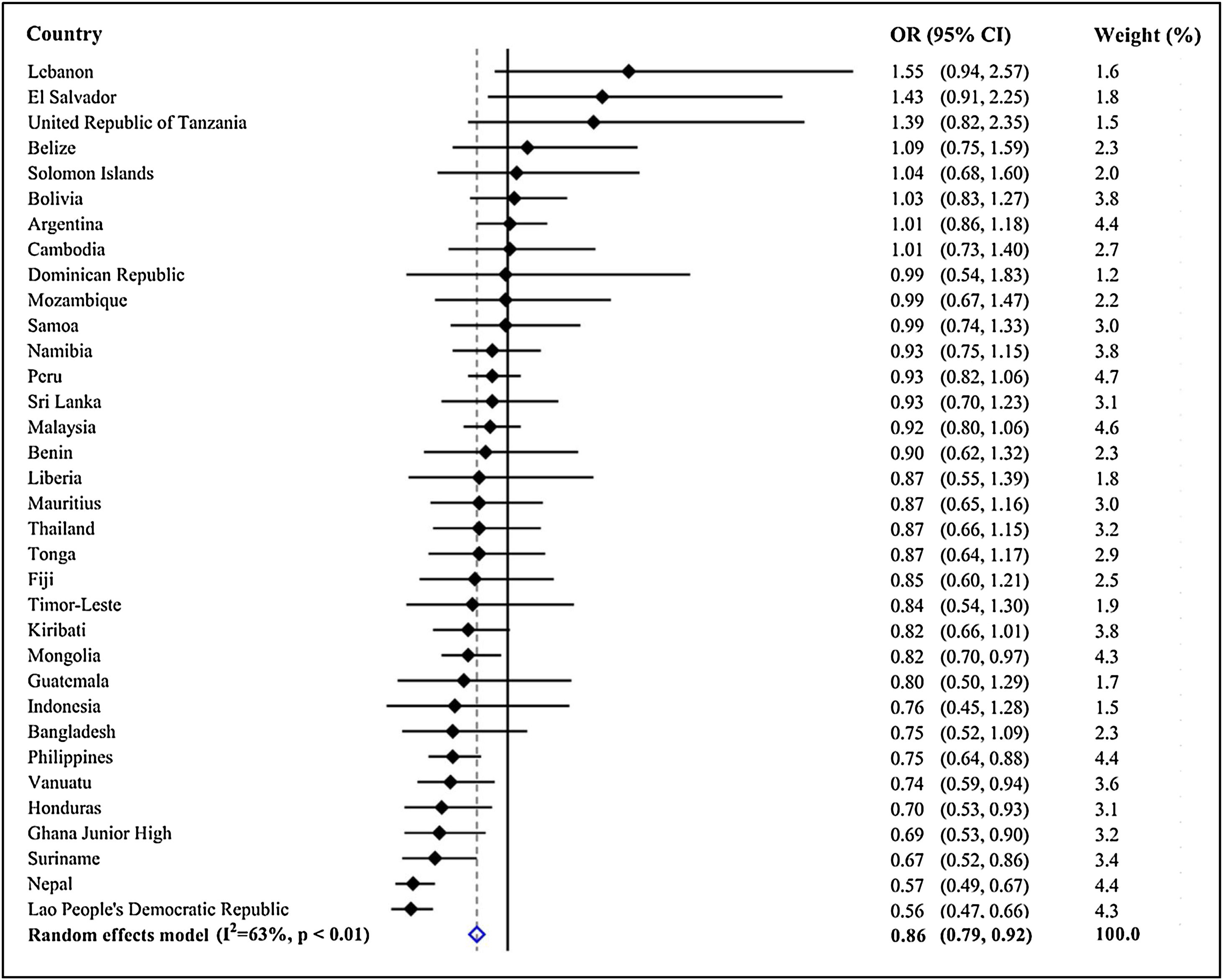

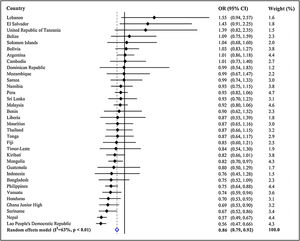

Country-wise analysis showed that AST was significantly and negatively associated with suicide attempts in all countries (Fig. 2). The pooled OR (95% CI), obtained by meta-analysis with random effects, was 0.86 (0.79-0.92) with large between-country inconsistencies. Of all the 34 included countries, the significant relationship between AST and suicide attempts was observed in 8 countries (Mongolia, Philippines, Vanuatu, Honduras, Ghana, Suriname, Nepal, and Lao People’s Democratic Republic).

DiscussionIn relation to the putative role of PA (including AST) in mood regulation, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has ever directly explored the association between AST and suicide attempts among school-based children and adolescents. Therefore, given the paucity of evidence in this domain, we sought to delineate the relationship between AST and suicide attempts, by using data from 34 LMICs. The main findings were; (i) adolescents with AST had an 18% decrease in odds for suicide attempts, compared to those without AST among more than 127,000 adolescents aged 13–17 years from 34 LMICs; (ii) there was a large level of between-country heterogeneity in the association between AST and suicide attempts; and (iii) the association between AST and attempt suicide may not vary by gender.

This is the first study examining the association between AST and suicide attempts among LMIC adolescents aged between 13 and 17 years old. Owing to the novelty of this study on the topic (AST and suicide attempts), there was no sufficient evidence or studies for direct comparison with our study. Indeed, there are no studies available to confirm or refute the research findings in the current study. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more empirical research, to further discern the relationship between AST and suicide attempts among adolescents. Despite little supportive and comparable evidence, some plausible explanations for promising results can be posited in the given context. First, AST has been shown to negatively associate with depressive symptoms among adolescents (Gu & Chen, 2020; Sun et al., 2015), and there is evidence to suggest that the presence of depressive symptoms is an important predictor of attempted suicide. Collectively, AST may result in exercise-induced physiological changes (Bell, Audrey, Gunnell, Cooper, & Campbell, 2019; Dore et al., 2020) that are associated with improved emotion regulation ability that could alleviate depressive symptom, which in turn makes the odds for suicide attempts lower (Andermo et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Vancampfort, Hallgren et al., 2018). Second, as a unique tenet of PA, AST is a multifaceted behavior interacting with social and environmental settings. Social and environmental interactions during school travel, like talking with friends, are associated with better subjective well-being (e.g., positive mood) (Edward et al., 2017; Ramanathan, O’Brien, Faulkner, & Stone, 2014), which, in turn, would likely reduce the likelihood of suicide attempts (Klonsky et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2017). However, these effects are assumed, and more empirical evidence is needed to confirm the veracity of such claims. Another possible explanation involves bullying and victimization among adolescents. Indeed, LMIC adolescents have a greater likelihood of being bullied and victimized, compared with those living in economically advantaged countries (Alfonso-Rosa et al., 2020). Of note, some individual studies have found that adolescents with AST might be associated with lower odds of bully-victim experience (Alfonso-Rosa et al., 2020; Sampasa-Kanyinga et al., 2016). Moreover, it has been shown that bullying and victimization can cause suicide attempts, where suffering from more bullying and victimization is a contributor to suicide attempts (Koyanagi et al., 2019). Collectively, engaging in AST may reduce the risks of being bullied and victimized that may occur in school buses or other means of passive transportation, which may subsequently decrease the risks of suicidal attempts in adolescents. However, the underlying mechanism linking AST and suicide attempts warrants further investigation. In the present study, we only focused on the social and environmental interpretations for the association between AST and suicide attempts. Future studies are strongly encouraged in order to clarify the mechanistic association between AST and suicide attempts among adolescents.

Unlike the association between overall PA and suicide attempts (Felez-Nobrega et al., 2020) among adolescents (boys: negatively correlated; girls: positively correlated), the present study indicated that AST was negatively associated with suicide attempts in both boys and girls. Despite the unclear mechanisms linking overall PA and suicide attempts in girls, body dissatisfaction may be a contributory factor (Lawler & Nixon, 2011). For instance, adolescents who demonstrated low PA level have been shown to associate with body image dissatisfaction that is predictive of suicidal ideation (Kim & Kim, 2009). However, there is no evidence to show that AST has a negative role in causing other mental disorders that are positively correlated with suicide attempts. In this regard, AST could be used as a protective approach to reduce suicide attempts irrespective of gender. Notably, the mechanism linking AST and suicide attempts, and the role of gender with respect to the mechanism should be clarified in future research. Addressing this interesting research gap would be beneficial to develop more effective prevention for suicide attempts.

The present study also found that there was large inconsistency in the association between AST and suicide attempts across the included countries (I2 = 63%, p < .01), indicating the studied association may vary greatly, owing to differences in social, psychological, cultural, and environmental attributes in those samples. There are some hypotheses to explain the discrepant associations. The substantial differences may be related to what individuals see and experience during their travel to and from school. For instance, it has been shown that events that occur during travel are also significantly related with mood (Ramanathan, O’Brien, Faulkner, & Stone, 2014). This implies that only having AST is insufficient to explain mood and any resultant mental disorders. Another putative reason for the observed difference may be that the correlates or determinants of suicide attempts in different populations are different and idiosyncratic. This would reduce the relative importance of AST in explaining suicide attempts. It is also possible that the substantial difference in the association across the countries may be related to respective mental health policies. Indeed, owing to multiple countries’ socioeconomic conditions, available resources, healthcare leadership and political situations, their investments in mental health policies and programs may vary considerably. If some countries lacked mental health policies and services, adolescent in those countries are likely to have poorer mental health and well-being, which in turn, may inflate the prevalence of suicide attempts. Despite these hypotheses, more detailed explanations are required to explicate the between-country differences found in this study, with greater consideration given to specific countries with regards to suicide attempts and AST among adolescents.

AST among adolescents has long been beneficially associated with numerous physical and mental health outcomes (Gu & Chen, 2020; Lubans, Boreham, Kelly, & Foster, 2011; Schoeppe, Duncan, Badland, Oliver, & Curtis, 2013; Sun, Liu, & Tao, 2015), and our study provides further insights into the potential prevention of suicide attempts resultant from poorer mental health outcomes. In LMICs, there is an informative need for promotion and encouragement of AST because of its accessibility and availability. This may require the integration of multiple sectors (e.g., health care and urban design) to design and implement policy and action plans for AST. Additionally, future research should focus on the aforementioned mechanisms linking AST with suicide attempts. This may involve investigating the biological effects of AST on health, but also the context of AST (e.g., where and how). Finally, further research should be conducted to examine whether interventions that increase AST, are also effective in reducing suicidal behavior.

The use of nationally representative data from 34 countries, from different continents, and the large sample size are major strengths of this study. In addition, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first one to investigate the association between AST and suicide attempts in LMICs, which provides clinical relevance for public health and education sectors. Nonetheless, this study has several limitations that should be considered. First, there were no data available on the type of AST, and such data may have led to a better understanding of the association between AST and suicide attempts. Second, all variables were self-reported, and therefore, the subjective nature of the assessments make them susceptible to recall and reporting biases. Third, there was a difference in the timeframe between AST (past 7 days) and suicide attempts (past 12 months). That being said, it is unlikely that AST largely changes within a timeframe of 12 months. Fourth, this study included adolescents attending school, and therefore our findings may not be generalizable to those not attending school. Using a single question to collect data on AST is insufficient at some point, which may omit some significant and valuable information such as types of AST (e.g., walking or cycling or their combination), time duration for AST, what will have experienced (e.g., noise, traffic). Future well-designed studies with better assessment tools are needed. Finally, since this was a cross-sectional study, no causal or temporal inferences can be made.

ConclusionsThis study presents previously unreported, multi-national, evidence of the association between AST and suicide attempts among adolescents from LMICs, indicating that AST may be associated with reduced suicide attempts. Future longitudinal research is required to elucidate the directionality of the variables in our study and outline potential mechanisms and explore culturally specific variations. The findings of our study can also help to inform suicidal behavior prevention but should be operationalized with caution when implementing AST for reduced suicide attempts in different LMIC countries.

FundingThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.31871115); the Health Education England and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) [grant numbers ICA-CL-2017-03-001]; the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust; the Medical Research Council and Guys and St Thomas Charity; and ASICS Europe BV.