Physicians have not learned their role as patients. Health programmes for doctors are focused on mental health. Nevertheless, anomalous behaviours of ill doctors exist independently of health problems. We present a study to describe behaviour and attitudes of doctors towards their own illness (CAMAPE) including the analysis of questionnaire validation.

Material and methodsA mix methodology study based on semi-structured interviews to ill physicians and focus groups with members of medical colleges, occupational medicine services and doctors of ill doctors was performed. A survey was designed. Survey validation process included content and face validity, construct validity through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and reliability by Cronbach's Alpha Index.

ResultsA total of 27 interviews to ill doctors and 4 focus group were performed. Content and feasibility assessment was made by experts. Psychometric validation was performed with a sample of 4308 answers (2450 women, 56.87%). A 5-factor (F) model explained 78.08% variance. First factor (F1) “The work might worsen health”. Second (F2) “Mental issues, toxic habits and the impact of a bad health on work performance”; Third (F3) presenteeism and sick leaves; Fourth (F4) the handling of an ill colleague and the role of medical colleges. Fifth (F5) the healthcare pathway and potential value of revalidation in medical profession.

ConclusionsA comprehensive mixed study on the process of physicians becoming ill has been launched with a reliable questionnaire in a large sample of registered doctors. The analysis will help to formulate gender-sensitive policy and ethical recommendations in relation to sick doctors given the progressive feminisation of the medical profession.

Los médicos no han aprendido su papel como pacientes. Los programas de salud para médicos tratan la salud mental. Los comportamientos anómalos existen independientemente de sus problemas de salud. Presentamos un estudio para describir los comportamientos y actitudes de los médicos hacia su propia enfermedad (CAMAPE).

Material y métodosEntrevistas semiestructuradas a médicos enfermos y grupos focales con colegios de médicos, servicios de medicina del trabajo, médicos tutores y médicos de médicos. Se diseñó una encuesta. La validación incluyó validez de contenido, constructo con análisis factorial y fiabilidad por índice alfa de Cronbach.

ResultadosSe desarrollaron un total de 27 entrevistas y 4 grupos focales. La evaluación del contenido fue realizada por expertos. La muestra de validación fue de 4.308 respuestas (2.450 mujeres, 56,87%). Un modelo de 5 factores explicó el 78,08% de varianza. El primer factor (F1) fue «El trabajo puede empeorar la salud»; el segundo (F2) «Cuestiones de salud mental, hábitos tóxicos e impacto de una mala salud en rendimiento laboral»; el tercero (F3) «Presentismo y bajas laborales»; el cuarto (F4) «Manejo de un compañero enfermo y colegios de médicos»; el quinto (F5) «Atención a los médicos enfermos y valor potencial del proceso de revalidación colegial».

ConclusionesSe presenta un estudio sobre el proceso de enfermar de los médicos con un cuestionario validado en una amplia muestra de médicos. El análisis ayudará a formular políticas y recomendaciones éticas con perspectiva de género en relación con los médicos enfermos, dada la progresiva feminización de la profesión médica.

The culture of self-sacrifice has been promoted in the medical profession and health organisations prioritising the needs of patients above all else, even above doctors’ own health needs.1 The World Medical Association expressed its concern in this respect and issued a declaration to this end.2 The declaration incorporated a key reference to doctors’ own health into its Physician's Pledge: ‘I will attend to my own health, well-being, and abilities to provide care of the highest standard’.

The fact that a physician can become a patient is never approached during undergraduate years, and once they are practising physicians, they have internalised that the patients can only be another.3

When doctors fall ill, they become atypical patients4 and have difficulties in taking on the role of patient. Consequently, behaviours of self-diagnosis,6 self-treatment7 and the use of alternative healthcare pathways8 are frequent. Doctors who treat ill colleagues very often do not act as they would with a standard patient and may feel pressured, tense, and uncertain.9 Therefore, the care received by ill doctors may be of poorer quality than standard. In the meanwhile, working while ill, physicians might pose risks to their patients.10,11

To be an ill physician has an impact on the process of providing care and professional competence4 and leads to high rates of presenteeism.5–7

It is difficult to find epidemiological information regarding ill doctors in European countries except from Scandinavian countries8–10 and Ireland.11 Nevertheless, there is an increasing number of publications regarding mental health issues in the medical profession.6,12–14 But the anomalous behaviour of ill doctors affects the way they cope with any illness.

Therefore, we conducted a research project: “Getting Sick is Human: When the Doctor is the Patient” with the aim to provide a whole understanding of the process of doctors falling ill through a qualitative approach considering ill doctors and professionals involved and a survey to get medical population behaviours and attitudes towards physicians own process of becoming ill. The present study aims to present the study protocol and the psychometric validation of the questionnaire “Behaviours and Attitudes of Doctors facing their Own Illness” (CAMAPE, Comportamientos y Actitudes del Médico Ante su Proceso de Enfermar).

Material and methodsThe study consisted in two stages. A qualitative approach was developed to get direct information from sick doctors and doctors involved in the healthcare process and second a national survey was designed.

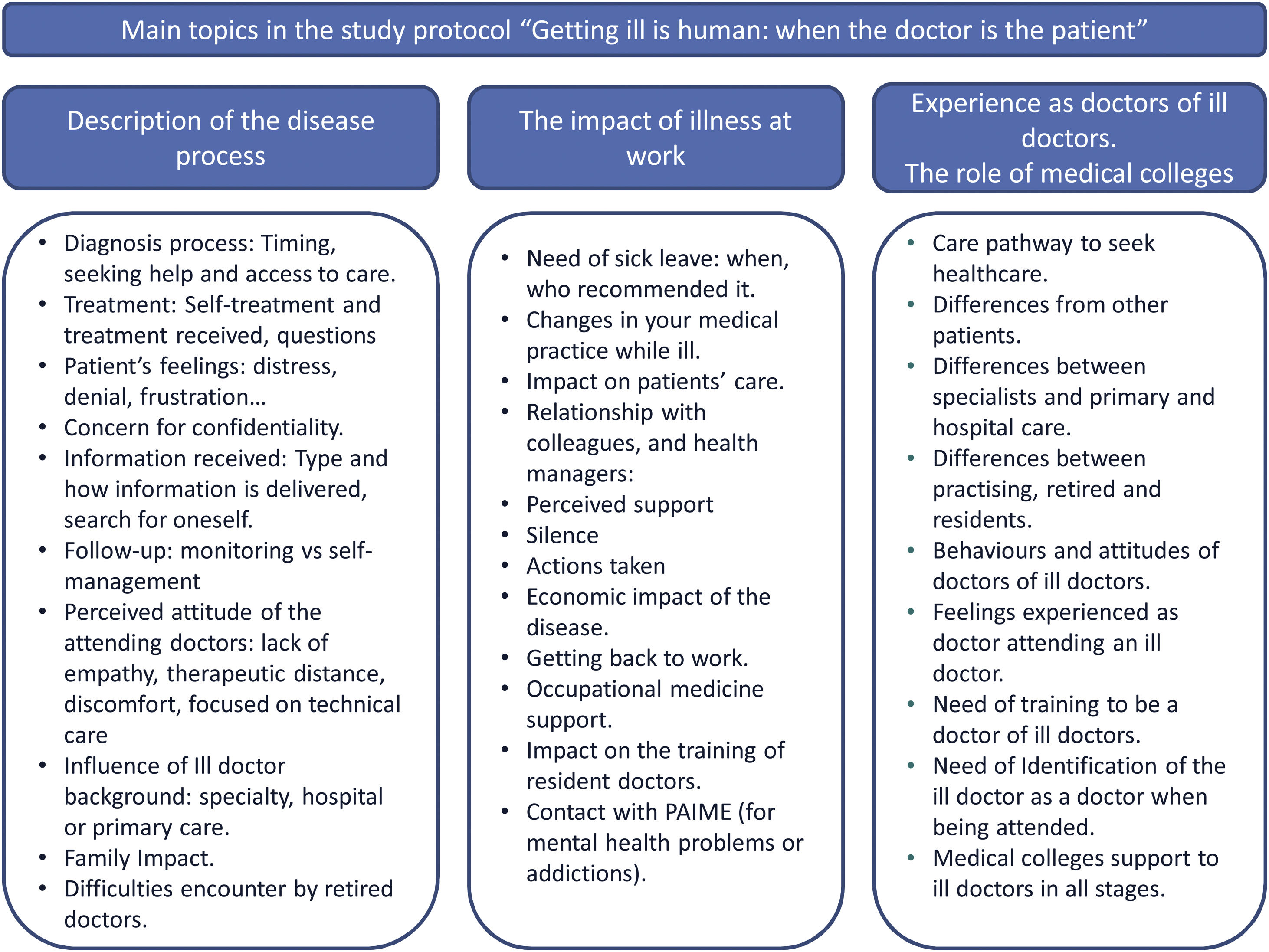

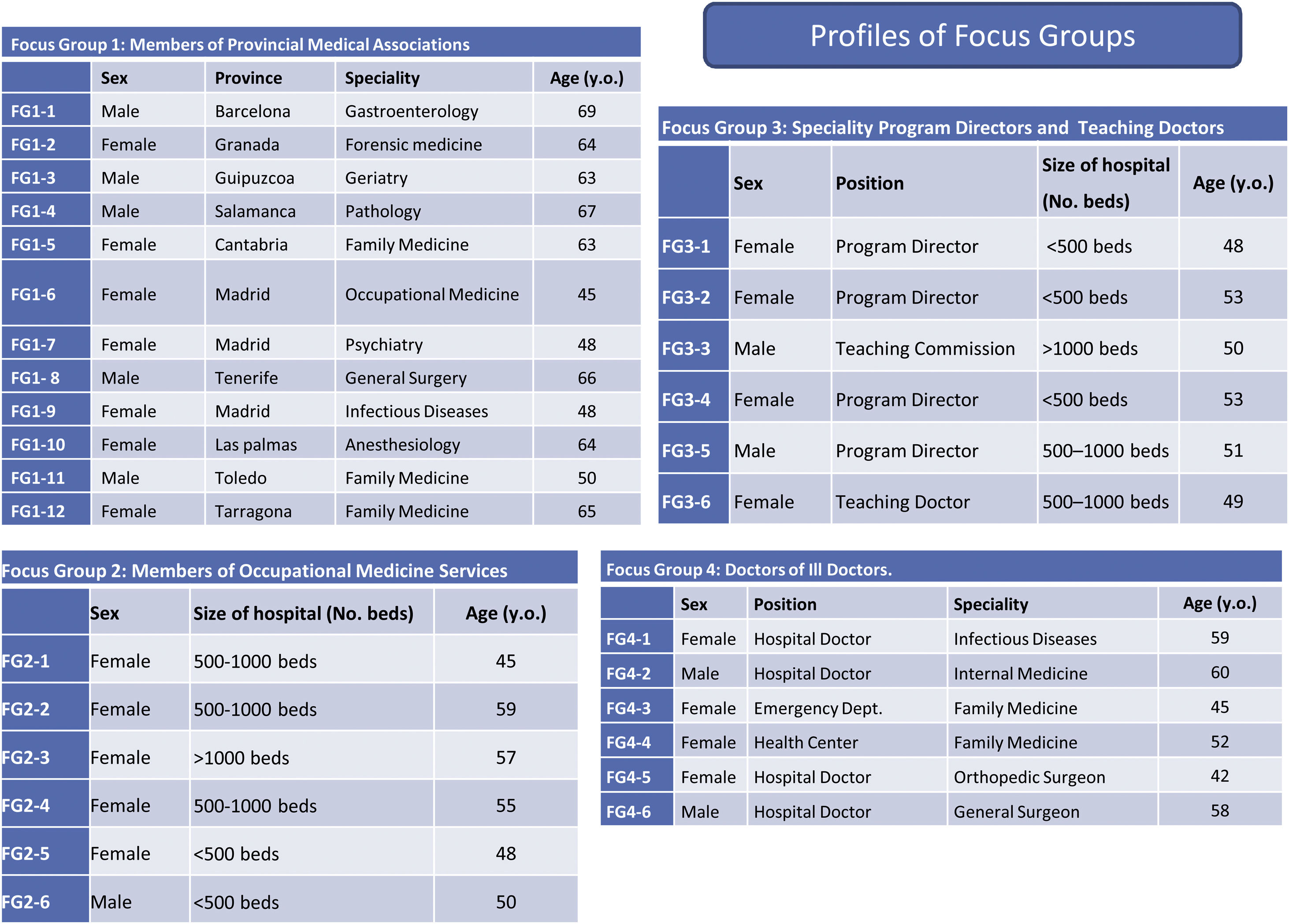

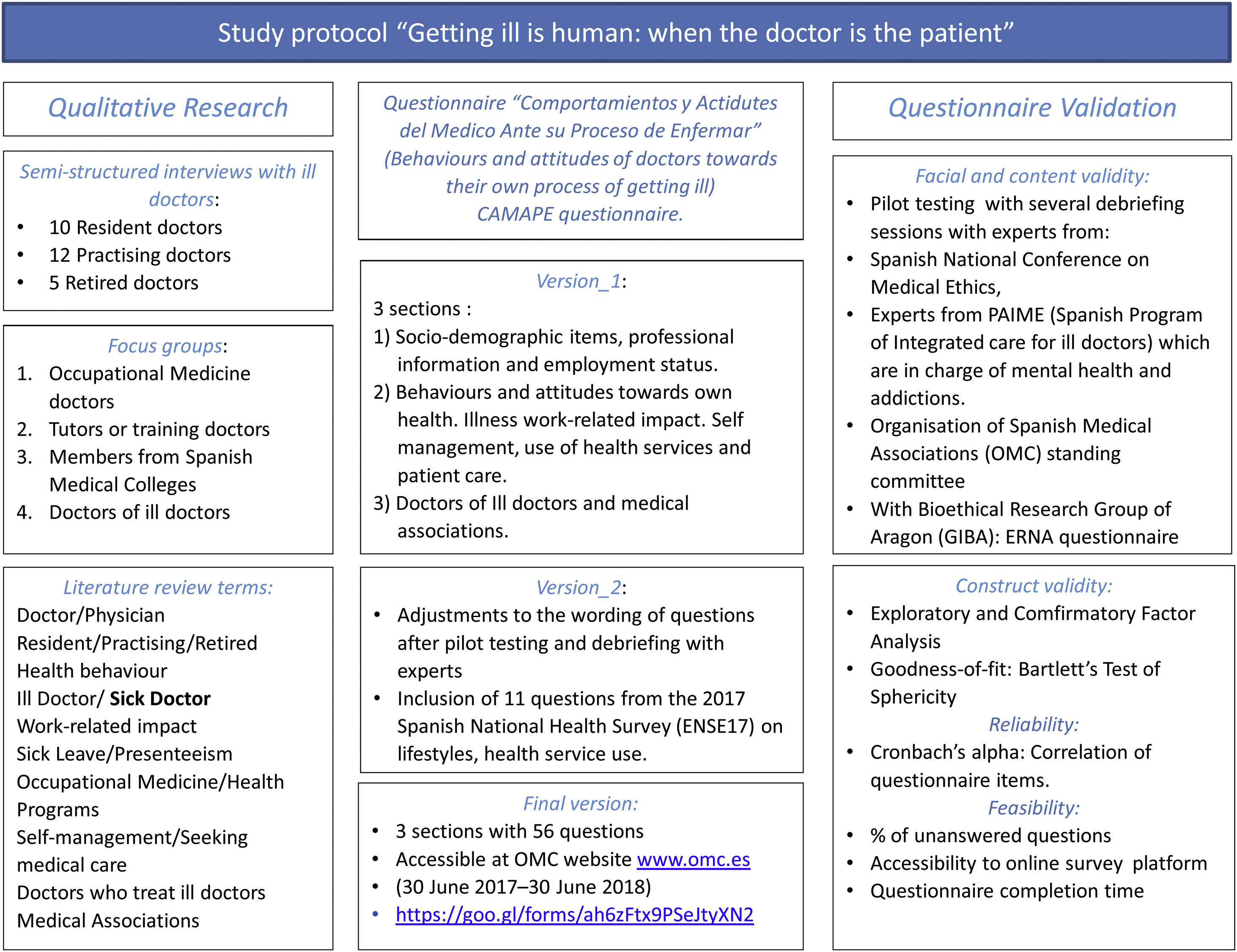

A literature search on the process of doctors getting ill raised key frequent topics as health issues, impact on work, presenteeism, seeking help, the role of ill doctors and medical associations, self-management that were issued to build the scripts (Fig. 1). We created a script for semi-structured interviews to ill doctors in different professionals’ stages (training, practising and retired doctors) and a script for focus groups. The focus groups considered main stakeholders on the care of physicians as occupational medicine professionals, teaching doctors, doctors of ill doctors and members of medical colleges. The profiles of the focus groups are detailed in Fig. 2. Both semi-structured interviews and focus groups were performed and analysed by two researchers with the support of MAXQDA 12.0 program and using discourse analysis and grounded theory.15

An initial questionnaire was designed with items sourced from literature search and the four main dimensions obtained from the qualitative analysis: health issues, impact on work, seeking help, the role of ill doctors and medical associations. The questionnaire was piloted with debriefing by experts. At the suggestion of experts, questions from the 2017 Spanish National Health Survey (ENSE17)16 were incorporated in order to allow comparison of certain lifestyle habits and use of health services with the population with the same level of education and age as other studies.11

The items were grouped into three sections: (1) socio-demographic items as speciality, employment status, public/private/combined practice and professional satisfaction; (2) items related to health issues (chronic illness, flu vaccination, smoking, alcohol use, relationship with general practitioner) and the impact of illness on work (sick leave, presenteeism, time in sick leave) as well as issues related to falling ill (self-diagnosis, self-treatment, alternative pathways to diagnosis and treatment, patient care and confidentiality); (3) items referred to topics as being consulted by ill colleagues, being doctor of a doctor, medical associations, ethical considerations regarding periodic revalidation and a final open question regarding proposals about improve the provision of healthcare to ill doctors.

Target populationThe target population was the 270,000 Spanish registered physicians. Random sampling was conducted with a (1−α):99% confidence interval, 3% precision and sample proportion of p=0.5 that would maximise sample size, with an expected attrition rate of 50%. The total sample consisted of 3662 physicians. The questionnaire was designed with a self-report format to be filled online in the Organisation of Spanish Medical Associations (OMC) website http://www.cgcom.es/. All physicians registered in any of the 50 Provincial Medical Associations in Spain had accessed to the online questionnaire. Provincial Medical Associations publicised the survey on their website, inviting registered physicians to respond to it. The survey was introduced by a video explaining the research project “Gettig sick is human: when the doctor is the patient”. The questionnaire was available from June 2017 to June 2018. The study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Aragon in 2016.

Questionnaire validationThe validation process was divided into two stages (1) assessment of face validity, content validity and feasibility and (2) assessment of construct validity and reliability.

The validation process17 consisted of assessing face validity and content validity through debriefings with experts from the field of medical ethics, Fundació Galatea (a Spanish foundation created to protect the health and well-being of health professionals),18 the standing committee of the Organisation of Spanish Medical Association and the research team.

In terms of feasibility, the assessment took into consideration the percentage of unanswered questions, and the access to the questionnaire which was only available to Spanish registered physicians.

Construct validity was assessed by exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA). Prior to this, the suitability of the factor analysis was evaluated by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. Adequacy was also evaluated through a correlation matrix by Bartlett's Test of Sphericity. In our case, the p-value associated with Bartlett's test was<0.001, confirming the use of this technique. The following goodness-of-fit statistics were obtained for CFA Normed fit index (NFI), the Root Mean Square Error of approximation (RMSEA) index and the comparative fit index (CFI) as well. To interpret the factors resulting from the CFA, we identified first the items whose correlations with the factors were highest in absolute value, given that they could be directly or indirectly related.

The reliability was measured through the internal consistency of the whole questionnaire and for each factor through the correlation coefficients and Cronbach's alpha Index. The protocol and validation stages are summarised in Fig. 3.

ResultsQuestionnaire developmentA total of 27 interviews to sick doctors and 4 focus group were developed. Regarding literature search, there wasn’t any Mesh topic regarding this issue. So, we mainly used “sick doctor” as the most specific descriptor used on scientific literature.

A final questionnaire with 56 questions was launched (Appendix-1: Final questionnaire). The questionnaire was completed by a total of 4308 physicians, of whom 1858 were men (43.13%) and 2450 women (56.87%). The participation of female junior doctors (73.06%) was higher than male (26.94%). By speciality, the percentage of women in medical specialities was higher than in surgical specialities. (59.37% vs 40.63%). Retired doctors comprised most men (73.08%). The mean age of the male participants (54.78±11.87 years) was higher than that of the female participants (45.95±11.76), with statistically significance among practising doctors and retired doctors (Table 1).

Distribution by age, sex, and professional category of sample.

| Professional category | Sex | Number of professionals | Mean | SDa | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junior doctors | Male | 97 | 31.67 | 9.91 | |

| Female | 263 | 28.90 | 5.95 | p>0.05 | |

| Medical specialists | Male | 1408 | 52.93 | 9.24 | |

| Female | 2057 | 46.84 | 9.69 | p<0.05 | |

| Retired doctors | Male | 353 | 68.48 | 5.09 | |

| Female | 130 | 66.43 | 5.58 | p<0.05 | |

| Total of doctors | Male | 1857 | 54.78 | 11.87 | |

| Female | 2449 | 45.95 | 11.76 | p<0.05 | |

| Total | 4306 | 49.76 | 12.59 | ||

Only three questions were not answer by all participants (Table 2). The highest percentage of non-responses was for question 21. The validation was carried out only with the answered values for each item. The rest of items were answered by 100% of the sample size.

Distribution and percentage of less answered items in CAMAPE.

| Items | Answers | Sample size | % non-answered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. What was the main reason that any of your health problems was the result of or worsened because of your professional activity? | 1952.00 | 4308.00 | 54.69% |

| 1. The level of responsibility in your profession. | |||

| 2. Overwork and working hours. | |||

| 3. The impact of a medical error or errors experienced with your patients. | |||

| 4. Another reason (give details in the following question) | |||

| 25. The main reason you went to work while you were ill was… | 3850.00 | 4308.00 | 10.63% |

| 1. Your responsibility to your patients | |||

| 2. To not overburden your colleagues | |||

| 3. Fear of losing your contract | |||

| 4. To keep up your regular income | |||

| 36. Is your GP your spouse/partner, a family member or close friend? | 4186.00 | 4308.00 | 2.83% |

The EFA and CFA were performed to analyse the distribution of items into factors. The KMO value (0.8193) was good and justified the use of this multivariate technique. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity obtained a p-value of<0.001, indicating that the items were related and confirming the use of EFA.

The NFI of 0.721, RMSEA index below 0.109 and a CFI of 0.859 indicated a good model fit for CFA. Five factors were selected as a solution to the EFA, fulfilling the Kaiser rule, selecting all factors whose eigenvalues were greater than one. The factor model with the five factors explained 78.08% of model variance, a high value. Table 3 shows the variance that explains each of the factors, and their aggregate value.

Actual variance for each factor and percentage of total variance.

| Factor | Number of items | Actual variance | Difference | % Variance of factors | % Total variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 5 | 3.09456 | 1.16497 | 26.75% | 26.75% |

| Factor 2 | 15 | 1.92959 | 0.18723 | 16.68% | 43.42% |

| Factor 3 | 13 | 1.74236 | 0.59075 | 15.06% | 58.48% |

| Factor 4 | 8 | 1.15161 | 0.03609 | 9.95% | 68.44% |

| Factor 5 | 13 | 1.11552 | 0.28656 | 9.64% | 78.08% |

The Factor 1 explained 26.75% of the model. It grouped items regarding “The work might worsen health”; Factor 2 explained 16.68% of the model. It included the relevance of mental health issues, the impact of a bad health on work performance and the weighting of toxic habits (consumption of toxic substances). Factor 3, explaining 15.06%, referred to sick leave and presenteeism; Factor 4, which explained 9.95%, grouped items on the handling of an ill colleague and the role of medical associations. Finally, Factor 5, which explained 9.64% of the model, brought together issues related to the care given to ill physicians and the potential value of revalidation in the health of medical profession.

The internal consistency and homogeneity of the instrument was analysed with Cronbach's Alpha Index for the questionnaire and for each factor. Overall Internal consistency was good (CAI 0.7889) as well as for each factor (F1: 0.8045; F2: 0.6764; F3: 0.5722; F4: 0.6790; F5: 0.6924) A high A high CAI for each factor showed that the items grouped were stable in each factor.

DiscussionA comprehensive study to analyse behaviours and attitudes of doctors towards their own process of getting ill was launched in Spain for the first time. The study is based in a mixed methodology to get a first-person experienced perspective combined with third-person perspective (those who are involved in the healthcare). Qualitative inputs with literature search and expert feedback got to a questionnaire with 56 items directed at compiling behaviours and attitudes in the medical profession concerning the process of doctors falling ill. The questionnaire was developed and properly assessed the psychometric validation supported by an important sample size of 4308 answers. The sample size reinforced the feasibility of the questionnaire.

The construct validity process through factor analysis allowed us to group the questions in 5 factors that connected items with resemblance of the main dimensions of the qualitative approach and as well as in international studies (9–11). Factors 1, 2 and 3 show that doctors have particular health habits related to tobacco and alcohol intake, physical activity11 which impact on their work. Self-medication is as well recognised in other studies9,10,19 and self-management of illness.20,21 Some studies show high prevalence of presenteeism5,22–24 and the anomalous way doctors seek for help while ill.25–27 Factors 4 and 5 are more related to the role of doctors who care for ill doctors28 and the role of medical associations, particularly the potential value of the revalidation process of the medical profession in the health surveillance of physicians.29 All the factors included questions on the process of physicians’ health-illness, but each one provided a nuance to the analysis as shown in other studies.9,10,19

The limitations of the instrument cannot be overlooked. On the one hand, sex distribution of participants clearly showed the feminisation of the current medical population.23–25 It may have been necessary to incorporate a gender perspective, as it has been explicitly done in other studies on doctors’ health.26 We focused on the impact of illness on the medical profession regardless gender issues. So certain variables were not directly taken into consideration, such as responsibility for children27 and the care of elderly persons,28 compatibility with household chores and the profession,29 which most likely have an impact on health and illness in women and which would influence decisions on the careers of future women doctors,30 particularly in surgical fields.32 Therefore, we considered the gender perspective to be a very important area of research to develop in the immediate future by the research group. On the other hand, a self-report survey is limited by the fact that it can rarely be independently verified. However, this factor has a lower weighting in individuals with high levels of education30 as the medical profession. In addition, the fact that it makes use of the Internet may have facilitated participation from younger professionals.31 The need to be registered physician to access the platform ensured the suitability of respondents.

A comprehensive study on the process of physicians becoming ill has been launched with a mixed methodology and a reliable multidimensional questionnaire in a large sample of registered doctors. The analysis will help to describe and quantify health behaviours and healthcare pathways of ill physicians, allowing to set evidence-based interventions and formulate policies and ethical recommendations and to involve all the players – medical practitioners and medical associations, occupational health services, governing bodies of health institutions, specialist training units and medical students – in order to guarantee a quality and safe care for the medical profession as a key element of healthcare quality, clinical ethics and professionalism without forgotten to include a gender perspective in the analysis.

Authors’ contributionsAll the authors are members of the Bioethics Research Group of Aragon that is leading the project “Getting Sick is Human: When the Doctor is the Patient”.

This project involves the writing of four doctoral theses related to the stages of the medical practitioner career: medical student, junior doctor, practising doctor and retired doctor.

Dr. Rogelio Altisent-Trota is the lead researcher on the project.

Dr. Bárbara Marco-Gómez is conducting the research focusing on practising doctors.

Dr. Candela Pérez-Álvarez is conducting the research focusing on junior doctors.

Dr. Alba Gallego-Royo is conducting the research focusing on medical students and statistical support.

Dr. María Teresa Delgado-Marroquín and Dr María-Pilar Astier-Peña are joint advisors of the methodology of the study and of the doctoral theses derived from it in conjunction with Dr. Altisent-Trota.

All the authors actively participated in every stage of the research: data collection, statistical analysis, discussion of results and writing of the present manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragon (CEICA) on 5 October 2016. Registration number CI P16/0236.

All participants in the survey agreed to participate by indicating this at the beginning of the online survey.

Availability of data and materialsAll data and materials are available upon request to researchers. Nevertheless, questionnaire database is included as a supplementary material with the manuscript submission.

FundingThis study was funded by the Spanish National Plan of I+D+I 2013-2016 (PI18/00968), Carlos III Health Institute-General Subdirection of Research Evaluation and Promotion of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “Another way to make Europe”, and financed by ERDF.

Conflict of interestsOn behalf of all the authors, Dr. María-Pilar Astier-Peña states that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the research presented involving any of the authors.

Dr. María Pilar Astier-Peña, corresponding author on behalf of the other signees guarantees the accuracy, transparency, and honesty of all the data and information contained in the study; that no relevant information has been omitted; and that any discrepancies between authors have been properly resolved and described.

We would like to thank all the professionals who participated in the semi-structured interviews and focus groups and to those who completed the survey for their time and contributions. Their experiences and perceptions are the main source of information for this study to understand the process of doctors who fall ill during different stages of their professional careers.