To report various components of health system responsiveness among poor internal migrants who availed the government health facilities in 13 Indian cities.

Materials and methodsCluster random sampling was used to select 50,806 migrant households, of which 14,263 households avail the government health facility in last six months. In addition, 5072 women, who sought antenatal care and 3946 women who had delivery in government health facility during last six months were also included. Data on different domains of health system responsiveness were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire, developed based on the World Health Survey of WHO.

ResultsOf the eight domains of responsiveness, namely, autonomy, communication, confidentiality, dignity, choice, quality of basic facilities, prompt attention and access to family and community, seven domains, except the ‘choice’, are assessed, and they are moderate. Only about 30% of participants said that doctor discussed on treatment options (autonomy). And 50–60% of participants said positively for questions of clarity of communication. About 59% of participants acknowledged the confidentiality. Not more than 40% of participants said they were treated with dignity, and privacy is respected (dignity). The responses to quality basic amenities, prompt attention and access to family and community domains are fairly satisfactory.

ConclusionsThis study has implications as many urban poor, including migrants do not utilize the services of public healthcare facilities. Hence, a responsive health system is required. There should be a policy in place to train and orient healthcare workers on some of the domains of health system responsiveness.

Informar sobre los diferentes componentes de la capacidad de respuesta del sistema sanitario entre migrantes internos pobres que utilizaron los servicios sanitarios del gobierno en 13 ciudades de la India.

Materiales y métodosEl muestreo aleatorio en grupos se utilizó para seleccionar 50.806 hogares de migrantes, 14.263 de los cuales han utilizado los centros sanitarios del gobierno en los últimos 6 meses. Además, se incluyó a 5.072 mujeres que solicitaron asistencia prenatal y a 3.946 mujeres que dieron a luz en centros sanitarios del gobierno durante los últimos 6 meses. Los datos sobre los diferentes ámbitos de la capacidad de respuesta del sistema de salud se recopilaron mediante un cuestionario administrado por un entrevistador, elaborado de acuerdo con la Encuesta Mundial de Salud de la OMS.

ResultadosDe los ocho ámbitos de capacidad de respuesta, es decir, autonomía, comunicación, confidencialidad, dignidad, elección, calidad de los centros básicos, asistencia rápida y acceso a la familia y la comunidad, se evalúan siete ámbitos, excepto la «elección», y son moderados. Solo alrededor del 30% de los participantes afirmó que el médico habló sobre las opciones de tratamiento (autonomía). Y el 50-60% de los participantes respondieron positivamente a las preguntas de claridad de la comunicación. Alrededor del 59% de los participantes reconoció la confidencialidad. No más del 40% de los participantes comunicaron que fueron tratados con dignidad y que se respetó su privacidad (dignidad). Las respuestas a los servicios básicos de calidad, la asistencia inmediata y el acceso a los ámbitos de la familia y la comunidad son bastante satisfactorias.

ConclusionesEste estudio tiene implicaciones ya que muchos ciudadanos pobres, incluidos los migrantes, no utilizan los servicios de los centros sanitarios públicos. Por tanto, se requiere un sistema sanitario receptivo. Debe existir una política para formar y orientar a los profesionales sanitarios en algunos de los ámbitos de la capacidad de respuesta del sistema sanitario.

The Human Development Report of United Nations Development Programme estimated that worldwide there are around 740 million internal migrants and 214 million international migrants.1 In India, both international and internal migrants are in large numbers. The 64th National Sample Survey (NSS) of India estimated that there were around 326 million internal migrants (i.e., 28.5% of the population) in 2007–08.2 And among these internal migrants, there is a substantial proportion of poorer migrants involved in low paid and low earning jobs, principally in the informal sector.3 The vulnerability of poor migrants is obvious in terms of livelihood insecurity, negligence and alienation in the new urban environment. This vulnerability leads to less control over available resources that are meant for all members of society. Thus, migrants often experience lack of access to healthcare services.4

Indian cities are known for the high concentration of healthcare facilities and still a considerable proportion of poor migrants could not access adequate service. Access is influenced by the vulnerability of the poor compounded by migration and health system-level factors such as complex procedures, less satisfaction with the services owing to low quality of care, including healthcare providers’ behaviour and previous experiences with the system.4–6 It appears that the health system is not responsive to the poor migrants. It is known that responsiveness increases patient satisfaction with the healthcare system,7 which in turn result in higher utilization of health care services.8 Hence, it is important to understand the need for health system responsiveness for poor internal migrants whose health status and health care access are poor. Health system responsiveness is one of the three goals of the health system,9 and is related to a system's ability to respond to the legitimate expectations of potential users about non-health enhancing aspects of care.9 It can be defined as the way in which individuals are treated and the environment in which they are treated encompassing the notion of an individual's experience of contact with the health system.10 Of all objectives of health systems, responsiveness is minimally studied, which probably reflects the lack of all-inclusive frameworks that go beyond the normative characteristics of responsive services. The present paper reports various components of health system responsiveness among poor migrants in 13 Indian cities.

MethodologyA large multi-centric interventional study was conducted to improve the healthcare access to the poor migrants in 13 Indian cities. This necessitated to understand health system responsiveness during the formative phase. The detailed methodology of the formative research of this interventional study is available elsewhere.11

Study areaThe study was conducted in 13 cities located across the country. In the descending order based on population, the cities included are Delhi (21.75 million), Mumbai (20.75 million), Kolkata (14.62 million), Bengaluru (8.73 million), Hyderabad (7.75 million), Jaipur (3.07 million), Lucknow (2.90 million), Visakhapatnam (1.73 million), Ludhiana (1.61 million), Nasik (1.56 million), Aligarh (0.91 million), Bhubaneshwar (0.89 million) and Imphal (0.42 million). The living conditions and other details of the study population are available elsewhere.12

Sample size estimation and study participantsCluster random sampling was used for selecting the migrant households. Clusters, particularly open spaces, migrant camps and non-notified slums were identified. Migrant households were selected by visiting and enquiring from the local community members and leaders. Individuals who are heading the households and had migrated and residing in these clusters within the last 10 years, but not lesser than 30 days were considered. Those who gave informed consent to participate in the study were included.

The required sample size was calculated by following Lwanga and Lemeshow.13 By considering the prevalence of utilization of government healthcare service (P) of 15%,11 which was considered as a minimum rate, with 10% relative precision and 95% confidence interval, the sample size was 2177. By considering the design effect of 1.7, as cluster sampling was adopted and 5% of non-response rate, the sample size for each site was 3886. Thus, a total of 50,806 households were surveyed.

Of these, 50,806 households, 14,263 households avail the government health facility in last six months. Head of the household was interviewed for data on health system responsiveness on general health care. Of the total sampled households, 5072 households had a woman who had taken the antenatal care and 3946 women who had delivered in government health facility during last six months. These women were also included and data were collected on health system responsiveness pertained to these services.

DataData were collected during formative (pre-intervention) phase from heads of households and women who sought treatment from government health facility. Specific information was sought on the different domains of health system responsiveness, using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. Questions on responsiveness were taken from the tools used in the World Health Survey (WHS) of WHO on measuring responsiveness.14,15 The questionnaires of WHS were developed and validated systematically.16

The measurement of responsiveness was obtained by asking participants to rate their most-recent experience of contact with the government health facility for both inpatient and outpatient health services, within a set of eight domains by responding to set questions. The domains consist of “autonomy” (involved in decisions), “communication” (clarity of communication of healthcare personnel), “confidentiality” (confidentiality of personal information), “dignity” (respectful treatment), “choice” (choice of health care provider), “quality of basic facilities” (surroundings of health facility), “prompt attention” (convenient travel and short waiting times) and “access to family and community/social support” (contacts with outside world and maintenance of regular activities). First four domains belonged to respect for the persons and latter four are client-oriented domains. For the present paper, we analysed for all domains except for fifth domain, i.e. “choice”. This domain is not relevant to the context of the sample as all sampled households have utilized the services of government health facility and hence, we have not asked them on the choice of health facility and health care provider. The present data on health system responsiveness are self-reported and measured on an ordinal categorical scale.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocols were approved by the institutional ethics committees (IECs) of the respective author's institutes. Each of the 13 IECs approved the study for the corresponding city. Eligible individuals were provided with a participant information sheet and informed consent form in a language they could read.

ResultsEach domain of health system responsiveness was assessed through 1–3 questions, and the responses to these questions are presented as percentages to total participants. Domain-wise pooled results for the country are presented in Tables 1–8. The city-wise results in Tables 1.1–7.1 are available online as supplementary material.

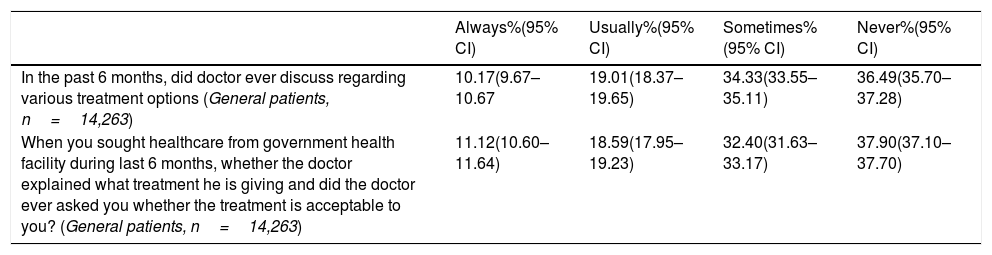

Responses of participants pertained to the domain ‘autonomy’.

| Always%(95% CI) | Usually%(95% CI) | Sometimes%(95% CI) | Never%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In the past 6 months, did doctor ever discuss regarding various treatment options (General patients, n=14,263) | 10.17(9.67–10.67 | 19.01(18.37–19.65) | 34.33(33.55–35.11) | 36.49(35.70–37.28) |

| When you sought healthcare from government health facility during last 6 months, whether the doctor explained what treatment he is giving and did the doctor ever asked you whether the treatment is acceptable to you? (General patients, n=14,263) | 11.12(10.60–11.64) | 18.59(17.95–19.23) | 32.40(31.63–33.17) | 37.90(37.10–37.70) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

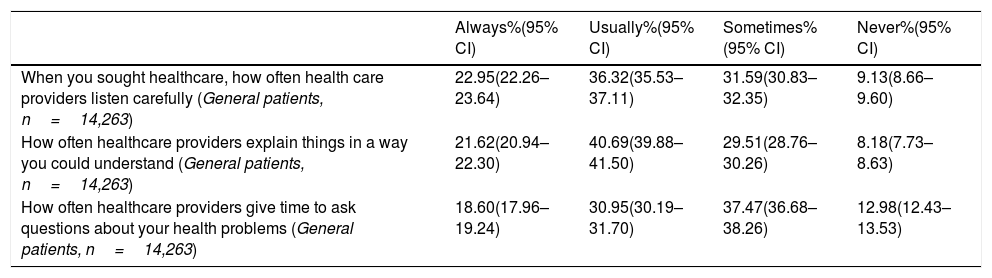

Responses of participants pertained to the domain ‘clarity of communication’.

| Always%(95% CI) | Usually%(95% CI) | Sometimes%(95% CI) | Never%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When you sought healthcare, how often health care providers listen carefully (General patients, n=14,263) | 22.95(22.26–23.64) | 36.32(35.53–37.11) | 31.59(30.83–32.35) | 9.13(8.66–9.60) |

| How often healthcare providers explain things in a way you could understand (General patients, n=14,263) | 21.62(20.94–22.30) | 40.69(39.88–41.50) | 29.51(28.76–30.26) | 8.18(7.73–8.63) |

| How often healthcare providers give time to ask questions about your health problems (General patients, n=14,263) | 18.60(17.96–19.24) | 30.95(30.19–31.70) | 37.47(36.68–38.26) | 12.98(12.43–13.53) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

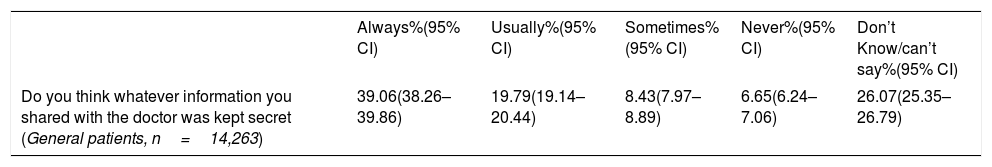

Responses of participants pertained to the domain ‘confidentiality’.

| Always%(95% CI) | Usually%(95% CI) | Sometimes%(95% CI) | Never%(95% CI) | Don’t Know/can’t say%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think whatever information you shared with the doctor was kept secret (General patients, n=14,263) | 39.06(38.26–39.86) | 19.79(19.14–20.44) | 8.43(7.97–8.89) | 6.65(6.24–7.06) | 26.07(25.35–26.79) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

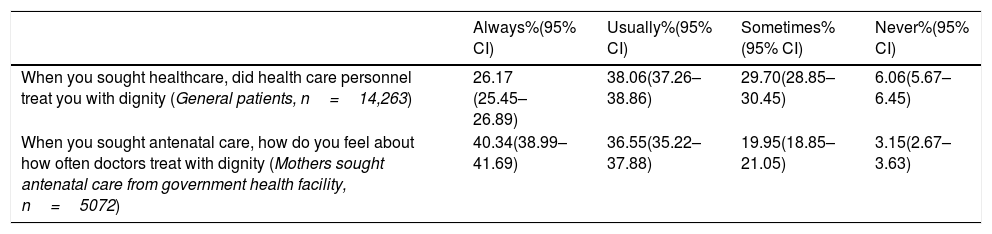

Responses of participants pertained to the domain of ‘dignity’ – ‘respect’.

| Always%(95% CI) | Usually%(95% CI) | Sometimes%(95% CI) | Never%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When you sought healthcare, did health care personnel treat you with dignity (General patients, n=14,263) | 26.17 (25.45–26.89) | 38.06(37.26–38.86) | 29.70(28.85–30.45) | 6.06(5.67–6.45) |

| When you sought antenatal care, how do you feel about how often doctors treat with dignity (Mothers sought antenatal care from government health facility, n=5072) | 40.34(38.99–41.69) | 36.55(35.22–37.88) | 19.95(18.85–21.05) | 3.15(2.67–3.63) |

| Yes%(95% CI) | To some extent%(95% CI) | No%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| When you are in health facility for delivery, whether healthcare providers treat with dignity (Mothers delivered in government health facility, n=3946) | 57.05(55.51–58.59) | 38.19(36.67–39.71) | 4.76(4.10–5.42) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

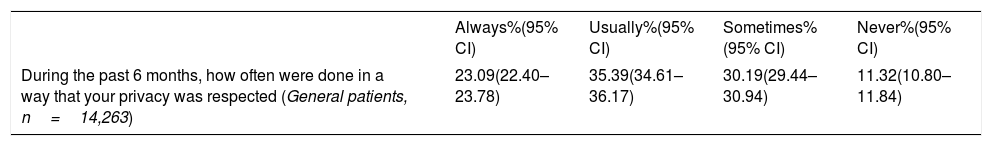

Responses of participants pertained to domain of ‘dignity’ – ‘privacy’.

| Always%(95% CI) | Usually%(95% CI) | Sometimes%(95% CI) | Never%(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the past 6 months, how often were done in a way that your privacy was respected (General patients, n=14,263) | 23.09(22.40–23.78) | 35.39(34.61–36.17) | 30.19(29.44–30.94) | 11.32(10.80–11.84) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

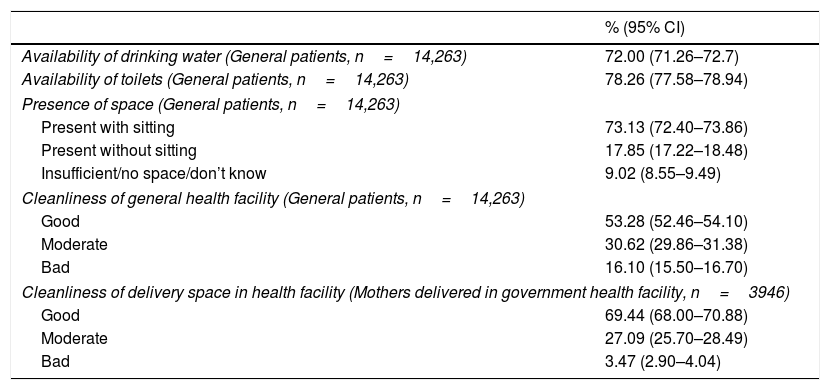

Responses of participants pertained to domain of ‘quality of basic amenities’.

| % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Availability of drinking water (General patients, n=14,263) | 72.00 (71.26–72.7) |

| Availability of toilets (General patients, n=14,263) | 78.26 (77.58–78.94) |

| Presence of space (General patients, n=14,263) | |

| Present with sitting | 73.13 (72.40–73.86) |

| Present without sitting | 17.85 (17.22–18.48) |

| Insufficient/no space/don’t know | 9.02 (8.55–9.49) |

| Cleanliness of general health facility (General patients, n=14,263) | |

| Good | 53.28 (52.46–54.10) |

| Moderate | 30.62 (29.86–31.38) |

| Bad | 16.10 (15.50–16.70) |

| Cleanliness of delivery space in health facility (Mothers delivered in government health facility, n=3946) | |

| Good | 69.44 (68.00–70.88) |

| Moderate | 27.09 (25.70–28.49) |

| Bad | 3.47 (2.90–4.04) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

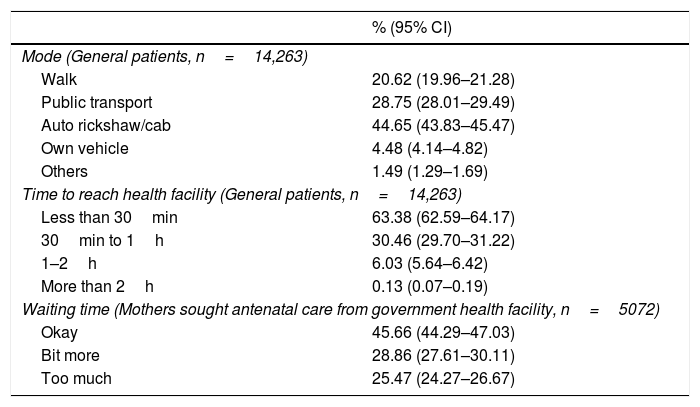

Responses of participants pertained to domain of ‘prompt attention’.

| % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Mode (General patients, n=14,263) | |

| Walk | 20.62 (19.96–21.28) |

| Public transport | 28.75 (28.01–29.49) |

| Auto rickshaw/cab | 44.65 (43.83–45.47) |

| Own vehicle | 4.48 (4.14–4.82) |

| Others | 1.49 (1.29–1.69) |

| Time to reach health facility (General patients, n=14,263) | |

| Less than 30min | 63.38 (62.59–64.17) |

| 30min to 1h | 30.46 (29.70–31.22) |

| 1–2h | 6.03 (5.64–6.42) |

| More than 2h | 0.13 (0.07–0.19) |

| Waiting time (Mothers sought antenatal care from government health facility, n=5072) | |

| Okay | 45.66 (44.29–47.03) |

| Bit more | 28.86 (27.61–30.11) |

| Too much | 25.47 (24.27–26.67) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

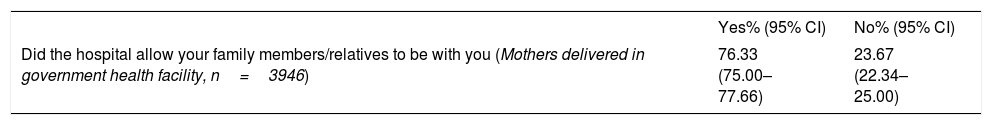

Responses of participants pertained to domain of ‘Access to family/community’.

| Yes% (95% CI) | No% (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Did the hospital allow your family members/relatives to be with you (Mothers delivered in government health facility, n=3946) | 76.33 (75.00–77.66) | 23.67 (22.34–25.00) |

Abbreviations: n, sample; CI, confidence intervals.

The domain autonomy of health system responsiveness was assessed through two questions (Table 1). Only about 30% of participants said positively to these questions that doctor discussed on treatment options and doctor informed about the treatment given and asked that the treatment is acceptable to the patient. The inter-city variability is visible with respect to autonomy. Less than 1% of participants in Bhubaneswar city, said that doctor always discussed regarding various treatment options, while a similar response was given by 60.3% in Ludhiana (Table 1.1). For second question, medial or negative response was given by about 80% of participants in Delhi, Kolkata, Visakhapatnam, Aligarh and Imphal (Table 1.2).

Domain – Clarity of communicationFor understanding this domain of clarity of communication, participants were enquired with three questions (Table 2). About 60% participants said positively for first two questions and about 50% participants said positively for third question (Table 2). Inter-city variations are visible and the ‘always’ response to the question to first question –– varies from 1% in Bhubaneswar to 77.2% in Mumbai (Table 2.1). For the second question, it varied from 2.3% in Bhubaneswar to 69.1% in Nasik (Table 2.2). And for third question, 0.4% (in Bhubaneswar) to 58.9% (in Nasik) of participants said that always the provider gives time (Table 2.3).

Domain – ConfidentialityAbout 59% of participants responded that the information is kept confidential either always or usually (Table 3). But about one-third of participants did not say positively on confidentiality. With regard to inter-city differences, about 6% (in Aligarh) to 95.5% of participants (in Bhubaneswar) said that the information would be kept confidential either always or usually (Table 3.1).

Domain – DignityFor assessing the dignity or respectful treatment, households sought treatment as well as mothers who sought antenatal and/or obstetric care were included. Altogether, about 26% and 38% of general patients and 40% and 37% of mothers, who sought antenatal care said that they were treated always or usually, respectively, with dignity (Table 4). Of the mothers, who availed obstetric care in a government facility, 57% said that they were treated with dignity. Remarkable inter-city differences are noted. Of the general patients – 4.3% (in Bhubaneswar) to 78.8% (in Mumbai), of the mothers, who sought antenatal care – 3.3% (in Bhubaneswar) to 91.5% (in Nasik), and of the mothers, who had their child delivery in government facility – 2.9% (in Bhubaneswar) to 95% (in Nasik) said that they were treated with dignity (Tables 4.1–4.3).

Privacy is another component of dignity under responsiveness. About 58% of participants said that they felt either always or usually that their privacy was respected (Table 5). Of the 13 cities, the privacy was respected always among 1.2% (in Bhubaneswar) to 69.5% of participants (in Ludhiana) (Table 5.1).

Domain – Quality basic amenitiesHaving quality basic amenities was assessed through four questions. About 72% of participants reported the availability of drinking water and 78% of participants reported the availability of toilets for patients in health facilities (Table 6). About 90% of participants reported that waiting space is available in health facilities; however, the presence of this space with sitting arrangement was reported by 73% of participants. With regard to the cleanliness of health facility, 53% of participants who sought general healthcare and 69% of mothers who delivered their baby in the health facility rated the cleanliness as good (Table 6). The cross-city results on these issues are presented in Tables 6.1–6.5 and remarkable variations are reported across these cities.

Domain – Prompt attentionPrompt attention is one of the client-oriented domains of health system responsiveness. It is noted that 21% of participants did reach health facility by walk, 29% of participants availed by the public transport system and 45% of participants availed haired auto-rickshaw or cab to reach the health facility (Table 7). About 63% of participants did reach the facility within 30min and 30% of participants reach in 30min to 1h. Across the cities, the mode and time of travel to reach health facility are not varied much (Tables 7.1 and 7.2). Those who sought antenatal care from government health facility were asked if they were happy with the waiting time. About 46% participants replied that waiting time was okay (Table 7). Too much waiting time is reported, varying from 5.1% (in Bhubaneswar) to 66.8% (in Kolkata) (Table 7.3).

Domain – Access to family and communityAccess to family and community refers to patients may be accompanied by family or friends during consultation or to get the opportunity to have personal needs taken care of by friends and family while receiving the health care. About 76% of mothers who delivered their children revealed that the health facility allowed the family members/relatives to accompany them (Table 8). This rate shows a considerable variability across the cities, ranging from 3.7% (in Kolkata) to 96.1% (in Jaipur) (Table 8.1).

DiscussionHealth systems responsiveness is a key objective of the health system of any nation. And elements of responsiveness can be interpreted as elements of people's trust in the health system. The present study revealed the responsiveness of the health system as perceived by the poor migrants living in 13 Indian cities.

Although very less proportion of people were always getting provided the various treatment options and asked for their acceptability for treatment, they were less refused for the sake of affordability. Sometimes when consent is required then only it was explained to them. People availing healthcare often seeks advice, and therefore, voluntarily sacrifice their autonomy for confidence generated by a doctor. Cathy et al. have listed different roles that family or friends can play during the decision-making process for the patient.17 In this study, the indicators of autonomy are poor and healthcare providers have not been prioritizing in providing treatment options to patients and asking for their acceptability. Hence, training and orientation of healthcare providers are important as autonomy is likely to be benefited not only in improving the welfare of the patients in their interaction with the health system but also in the health outcome of care due to better compliance.18

Regarding the clarity of communication, more than half of the study people are positively responded. Empirical evidence, however, suggests that the patients are not often well-informed and often dependent on health care providers for information. Gross et al. also found that patients’ satisfaction levels can be enhanced with the overall time spent, a small amount of time for chatting about non-medical topics and sufficient time for exchange information with the patient.19 With regard to confidentiality, patient's information related to her/his health condition should not be disclosed during the treatment except in some specific circumstances. In the present study, only about 60% of participants reported the confidentiality of their information. Regarding dignity, most of the participants get the decorous conduct while seeking treatment, but some find it degrading. More than one-third of the present study participants did not say that they were treated with dignity. Studies revealed that many patient priority lists contained the desire for ‘humanness’ in health sector interactions.20 This issue is important not only in face to face interactions but in the case of health education and information dissemination as well. Gilson et al. stressed the importance of the right to privacy in conditions such as childbirth.21

It is expected that health facilities – goods and services must be of quality. These indicators are relatively better among these communities, as they are resource dependent. After rolling of India's flagship programme, National Health Mission, many health facilities in Indian cities are better equipped and well-maintained.22 The domain of prompt attention refers to have timely services. This is very critical in case of emergencies and in child deliveries. One-third of participants of the present study needed more than half-an-hour and about 80% of participants needed some transport system to reach the health facility. Valentine et al. based on a general population survey in 41 countries revealed that most study participants selected prompt attention as the most important domain.23 However, a systematic review of health care system's performance in low and middle-income countries revealed that government health facilities lacked timeliness and hospitality to people.24 Relatively poorer scores, particularly waiting time can be shortened by proper reengineering of patient admission process and attendance of healthcare personnel. More than half of the participants of the present study are not satisfied with the waiting time. Longer waiting time may lead to dissatisfaction and negative attitude towards the system even before receiving care.23

Unwanted limitations on patients’ access of family and community members are not desirable. In this study, about three-fourths of mothers had access to their family members during their child delivery. Access to family and community ameliorates the negative impact of the illness. However, this domain was identified as the less important domain in general population survey from 41 countries.23 However, for European countries, social support was the best-performing domain of health system responsiveness.10

In India, substantial proportion of internal migrants is poor, and they lack of or less access to government health care. Hence, these people require a responsive migrant-sensitive healthcare.4 While planning healthcare for migrant labour, it is important to create circumstances under which negative health impact of migration may be mitigated.25 It is well documented that health system-related factors, including the lack of responsiveness are responsible for poor access to healthcare.4 The vulnerability of poor migrants is obvious in terms of livelihood insecurity, negligence and alienation in the new environment. Studies of health system responsiveness from other countries reported that high percentage of people felt discrimination based on poverty, social class and race.26,27 Similar situation of low healthcare access by the migrants is reported from both developed and developing countries.4,28–30 Hence, a responsive health system is required. However, most of the cities struggle to accommodate migrants legitimately and rarely migrants are considered in healthcare planning.

While interpreting the results, following strengths and limitations are to be taken into consideration. A major strength is that the study is based on a nationally represented sample of internal migrants from 13 Indian cities covering 50,806 households. However, there are some potential limitations. Recall bias cannot be excluded, however, the recall period was the maximum of six months, and bias could be minimum. The analysis was based on self-reported data, which was subjected to reporting bias. There was likely to be high heterogeneity among health care providers and facilities. However, the study provides overall experience of patients on government healthcare. During analysis, no scoring was given to responses, rather we presented the percentages of responses of questions on various domains of health system responsiveness. Hence, we could not compare these findings with international studies. However, these results are easily understandable to policy makers and healthcare managers.

In conclusion, responsiveness domains especially, autonomy, confidentiality and dignity are to be improved. There should be a policy in place to train and orient healthcare workers on some of the domains of health system responsiveness. Policy should also focus on improving resource-dependent domains by injecting more resources. Considering the low socio-economic status of this population that leads to vulnerability, an enquiry into low access to healthcare is important. The health system responsiveness in the background of vulnerability and inequity is to be understood. Addressing the inequity should be the long-term goal along with improving health system responsiveness domains. In countries like India, the foundations of Universal Health Coverage are grounded in the public health system, and hence, these efforts are important.

Ethics statementThe study protocols were approved by the institutional ethics committees (IECs) of the respective author's institutes. Each of the 13 IECs approved the study for the corresponding city. Informed consent was taken from all the participants.

FundingThis study was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India as two national task force projects. The first author (BVB) is the national coordinator of these projects.

Conflicts of interestsAuthors declare that they have no competing interests.

These authors contributed equally to the research and should be considered as joint third author. Authors are listed corresponding to the sequence of cities shown in the paper. Each author is responsible for research in corresponding city, except the first two authors. BVB is national coordinator of this research and YS analysed the data.