Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) are a growing focus for policymakers and academics seeking to foster innovation and economic growth. While existing literature has analysed various aspects of EEs, limited research has examined how public policies can contribute to their development. Through a single-case study, this study addresses this gap by analysing the role of a regional government in overcoming the challenges of building an EE. We explore the creation and development of the Biscay Startup Bay (BSB) EE in Bilbao City (Bizkaia, Basque Country, Spain). We describe the unique framework that they crafted and implemented, highlighting the key attributes that generate value for all stakeholders. This single-case study of the BSB EE in Spain offers valuable insights for policymakers seeking to design and implement successful Open Innovation-driven approaches to creating and developing regional EEs.

In developed countries, there is currently a heightened focus on garnering public policy support to increase the number of high-growth entrepreneurship ventures (HGEV) (Weissenböck & Gruber, 2024). However, merely providing a supportive framework is insufficient. The effectiveness of transactional forms of support for HGEV (e.g., financial assistance) is proving to be limited, particularly at the post-startup level (Isenberg, 2010). One response to this challenge is the adoption of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) approach. Thus, fostering EEs has become a crucial element of economic development in cities, regions, and countries worldwide (Mason & Brown, 2014).

The creation and subsequent growth of an EE depend on efficient and effective collaboration among interconnected stakeholders. These stakeholders include universities, governments, entrepreneurs, and private corporations. Research on EEs covers a broad range of topics, methods, and fields of application, such as the role of family entrepreneurs in driving regional innovation through an EE (Bichler et al., 2022), the importance of collaboration among various interconnected actors for fostering and maintaining entrepreneurial growth (Bouncken & Kraus, 2022; Fernandes & Ferreira, 2022), the role of inter-organisational networks in shaping the creation and evolution of EEs (Scott et al., 2022), the digital transformation of traditional markets into EEs (Song et al., 2022), and the influence of large corporations and institutions on predicting entrepreneurial activity (Xin & Park, 2024).

However, limited research has analysed the specific contributions of regional governments to the design, creation, and development of EEs in peripheral places (Bichler et al., 2022; von Bloh, 2021; Xu & Dobson, 2019).

The capacity of the Internet to facilitate and foster the global flow of information and knowledge creates conditions for a more enriching and open ecosystem, albeit much more complex. Recently, there has been a whirlwind of innovation in powerful technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and advanced robotics. These advancements, including blockchain and APIs, have opened the door for businesses to completely redefine their operations (Dahlander et al., 2021). This continuous change, occurring at an unprecedented speed, compels organisations to better anticipate and be more prepared to adopt new approaches to creating, innovating, manufacturing, commercialising, and even financing (Campos-Blázquez, 2019).

These changes have made companies more permeable to the external world and ideas. This new approach is evident in the concept of Open Innovation (OI), a term coined by Chesbrough (2003), which contrasts with the traditional Closed Innovation (CI) perspective. Chesbrough described OI as the paradigm of innovation which assumes that firms can and should leverage both internal and external ideas, as well as consider both internal and external paths to the market. This has led large companies to be more inclined to participate in EEs, exchanging knowledge and information with startups to address exploratory strategic challenges (Vanhaverbeke, 2006) that could result in disruptive innovation, subsequently aiding startup growth.

Over the past two decades, extensive research has been conducted on OI processes from various perspectives. Studies have explored leveraging external knowledge and experience for idea generation and problem-solving through crowdsourcing platforms (Brabham, 2013; Howe, 2006), as well as managing both external and internal intellectual property (Chesbrough, 2003, 2006; Chesbrough & Ghafele, 2014; Resnick, 2011). Additionally, research emphasises that business models are crucial for capturing value from innovation (Boudreau & Lakhani, 2009; Teece, 2010). Within OI, where success relies on knowledge flowing across organisational boundaries, most research has concentrated on how these inflows and outflows can be optimised to benefit innovating corporations (Bagherzadeh et al., 2020; Gutmann et al., 2023).

Despite the growing body of research on OI, a deeper understanding of its role in business ecosystem development remains elusive (Ferreira & Teixeira, 2019). Gao et al. (2020) further highlighted gaps in existing research and proposed directions for future OI studies. These include conducting empirical studies in diverse contexts to enhance the external validity of OI research, incorporating additional theoretical perspectives for novel insights, shifting the research focus from a firm-centric perspective to encompass macro- and micro-level analyses, and investigating collaborative innovation with stakeholders—an underexplored perspective with promising potential for deeper research.

Our research focuses on two key areas: exploring the design, creation, and development of a regional EE under an OI perspective (Sekliuckiene et al., 2016), with policymakers playing a key role, and identifying the best practices within an OI framework that can support and maintain an EE. This study aims to contribute to Chesbrough's (2019, p. 2) call for “a renewal of our understanding of Open Innovation, and how we can get better business results from using Open Innovation.”

Our research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1: How can policymakers leverage OI principles to design, create, and develop a regional EE that facilitates efficient knowledge exchange and inclusive collaboration among all stakeholders?

RQ2: What specific characteristics of an OI framework contribute to the development of an EE, and how can they be effectively implemented?

To address these questions, we conducted a single-case study using a systematic approach. This approach is based on a rigorous and predefined protocol to examine the experience of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia (PCB) in creating and developing the Biscay Startup Bay (BSB) EE in Bilbao, the capital of Bizkaia in the Basque Country (Spain).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section "Theoretical background" draws upon existing literature to discuss the concepts of entrepreneurship, EEs, and OI. Section "Method" outlines the research design for the data collection and analysis. Section "Entrepreneurial activities in the Basque Country" explores entrepreneurial activity in the Basque Country and Bizkaia and provides insights into the region's entrepreneurial landscape. Section "Case results and discussion" presents and discusses the framework developed by the BSB and its main components. Finally, Section "Conclusions and implications" presents a comprehensive conclusion, highlighting this study's theoretical and practical implications, noting its limitations, and suggesting avenues for future research.

Theoretical backgroundEntrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystemsEntrepreneurship studies have a long history. In 1755, Cantillon was the first author to propose the term in its economic sense (Nijkamp, 2003), but the concept is complex and lacks a single definition (Xin & Park, 2024). Sahlman and Stevenson (1991, p. 1) wrote that "entrepreneurship is a way of managing that involves pursuing opportunity without regard to the resources currently controlled. Entrepreneurs identify opportunities, assemble required resources, implement a practical action plan, and harvest the reward in a timely, flexible way". According to Baker et al. (2003, p. 256) it is reflected as "a linear process in which entrepreneur volition leads to gestational and planning activities", and involves "… the process of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities". It is worth noting, however, that there has been criticism regarding this linear perspective. It does not emphasise the complex, interconnected, iterative, and non-linear nature of entrepreneurship, which is influenced by contextual conditions within the EE approach (Blank & Eckhardt, 2023; Felin et al., 2024).

From Baker et al. (2003) definition, three areas of research in the field of entrepreneurship emerge: (i) why, when, and how opportunities for the creation of goods and services are generated; (ii) why, when, and how some people and not others discover and exploit such opportunities; and (iii) why, when, and how different courses of action are used to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Answering these questions is often more manageable within an EE.

Traditionally, the focus has been on entrepreneurs as individuals with common intrinsic traits such as creativity, freedom/autonomy, risk-taking, resilience, and continuous learning (Campos-Blázquez et al., 2020). However, in recent years, attention has been focused on the environment in which entrepreneurial activities are undertaken (von Bloh, 2021; Xu & Dobson, 2019), otherwise known as EEs. Grounded in ecological metaphors originally proposed by Moore (1993), popularised by Isenberg (2010), and aligned with the institutional, technological, and industrial changes observed in numerous economies, it has become evident that an accurate analysis of the entrepreneurship function must extend beyond individual entrepreneurs. Consequently, the examination of EEs gradually evolved into a distinct research field.

Consequently, the concept of EE swiftly gained legitimacy, becoming a popular topic that attracted scholars from various disciplines and policymakers eager to understand how economic agents and local conditions interact to stimulate productive entrepreneurship. Despite being considered an integrative component of existing theories such as economics and evolutionary theories, the ecosystem approach has proven to be effective in providing a robust theoretical framework for both research and policy. Specifically, it is seen as a regional economic development strategy based on the creation of supportive environments that encourage innovative startups (Spigel & Harrison, 2018). Earlier research recognised a co-evolutionary relationship between entrepreneurs, institutions, and other actors within the ecosystem, all of which support regional economies and startup development (Feld, 2012).

Defining an EE is a primary concern. Scholars concur that entrepreneurship surpasses business formation rates at a territorial level. Unlike traditional entrepreneurship studies, the EE framework emphasises the role of a spatially defined context in supporting entrepreneurial actions, and how it impacts both the ecosystem's constituents and territorial outcomes. In this regard, Cohen (2006, p. 3) defined EE as "an interconnected group of actors in a local geographic community committed to sustainable development through the support and facilitation of new sustainable ventures". More recently, Autio et al. (2018, p.74) emphasised the importance of digitalisation and defined the ecosystem as "a digital economy phenomenon that harnesses technological affordances to facilitate entrepreneurial opportunities pursued by new ventures through radical business model innovation".

Although there is no unique definition, EEs have four common features: "(i) there are various actors and resources involved in the ecosystem such as entrepreneurs, customers, firms, venture capital, universities, culture and market; (ii) it is essential for actors within the ecosystem to maintain continuous healthy and dynamic interaction; (iii) the ecosystem needs to be productive, with productivity potentially realised in different forms such as jobs or revenue growth; and (iv) whilst ecosystems may vary in size, there should be an element of spatiality/locality" (Xu & Dobson, 2019, p. 410). In summary, the EE is perceived as a dynamic, spatially defined framework that facilitates interaction among various economic and political agents, thereby fostering productive entrepreneurship through improved resource mobilisation processes, and contributing to territorial outcomes (Acs et al., 2023).

The Open Innovation paradigmThe concept of OI has emerged as a transformative paradigm for managing innovation processes. Initially, Chesbrough's (2003) seminal work relied heavily on qualitative evidence, particularly in-depth case studies of technology companies, to establish the value of this new approach. A key takeaway from this early research is the expanding scope of OI. While collaborations and partnerships between organisations remain crucial, the concept now encompasses a broader landscape including supply chains, networks, ecosystems, and public-private partnerships. This shift in focus emphasises that OI extends beyond the firm itself, recognising the significance of the surrounding innovation ecosystem (Chesbrough, 2024). Furthermore, as Radziwon et al. (2024) suggested, fostering a thriving OI environment requires the development of physical or digital ecosystems and a growth infrastructure to support the activities of innovating organisations.

The OI paradigm assumes that companies can and should integrate ideas, knowledge, and resources, using both internal and external sources. This approach fosters the development of new products, services, or processes, and can expand design capabilities, mitigate risk, and increase an organisation's revenue. In contrast to the CI model, where companies primarily rely on internal resources and limit external participation, OI involves collaboration with external partners, such as customers, suppliers, universities, startups, or other organisations (Chesbrough, 2003, 2024; Loren, 2011). Table 1 summarises the key differences between OI and CI.

Main differences between OI and CI.

| Element | Open Innovation | Close Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Source of ideas | Actively seeks external contributions and ideas | Primarily relies on internal capabilities |

| Level of Collaboration | Collaboration with a broad external network | Limited collaboration, often internal teams |

| Developmental Approach | May involve co-creation with external stakeholders | Internal development of products or services |

| Intellectual Property (IP) | Agreements to share or license IP with external partners | IP typically kept internal |

| Flexibility | Favours flexibility and adaptability through open collaboration | Tends to be more hierarchical and structured |

OI is "a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms in line with the organization's business model" (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014, p. 17). By effectively managing these knowledge flows, organisations can leverage external expertise and accelerate innovation.

According to this definition of OI, firms are encouraged to embrace both internal and external sources of ideas along with internal and external paths to the market to advance innovation. OI processes facilitate the integration of internal and external ideas into platforms, architectures, and systems. Business models play a crucial role in defining the requirements for these architectures and systems in the context of OI.

Furthermore, OI emphasises the importance of leveraging both internal and external ideas when designing business models. This ensures value creation while outlining the internal mechanisms for capturing a share of that value.

OI relies on two important knowledge flows: Outside–In and Inside–Out. Outside–In OI involves opening a company's innovation processes to a variety of external knowledge inputs and contributions. While Outside–In has received significant attention in both academic research and industry practice, with a focus on areas such as technology scouting, crowdsourcing, open-source technology, and technology licensing, it is important to recognise that OI encompasses a broader scope (Chesbrough, 2024).

OI also involves a critical but less-explored dimension: Inside–Out knowledge flow. This approach requires organisations to make underutilised knowledge available for external use by others in their business and business models. This can involve licensing technology, spinning off new ventures, or forming new joint ventures with external partners. In contrast to the well-researched Outside–In approach, Inside–Out OI is less understood in both academic research and industry practice.

A recent development in OI is the concept of Outside-Out OI. This approach represents an evolution of OI practices, extending its principles beyond the traditional focus on new product or service development. By embracing a broader range of partners, adopting flexible governance structures, and aligning with the innovation ecosystem, organisations can leverage Outside-Out OI to drive innovation across various aspects of their business (Vanhaverbeke & Gilsing, 2024).

In summary, OI aims to leverage the knowledge and skills of a broader network to create a more collaborative and flexible approach to innovation. By integrating external inputs and fostering open collaboration, companies can enhance their innovation potential and better navigate the complexities of the current market environment. The adoption of OI involves not only strategic and operational changes but also cultural and technological transformations that collectively drive an organisation towards sustained innovation and competitive advantage (Chesbrough, 2024).

MethodResearch designAccording to the literature, EEs represent an emerging topic. For this reason, we adopted a qualitative methodological approach, specifically a single-case study, to gain a detailed understanding of the studied phenomenon (Table 2). This approach involves constant comparison, cycling between data collection, data analysis, and further data collection based on emergent themes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). We examined the BSB's experience in creating and developing its EE, with a special focus on the applied public policies, type of networks fostering collaboration, innovation activities pursued, and achieved innovation outputs. Its application in this research is grounded in an exploratory, descriptive, and theory-building approach (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007).

Case study data.

| Purpose of research | Analyse the role of public policies in building and consolidating regional entrepreneurial ecosystems. Identify the characteristics of Open Innovation that help to develop an EE, and how they can be effectively implemented |

| Methodology of research | Single holistic case study (single unit of analysis). Descriptive, exploratory, and theory-building study |

| Single unit of analysis | Biscay Startup Bay entrepreneurial ecosystem |

| Type of sample | Logical and theoretical sample (capacity of transferability of the phenomenon studied), non-random (sampling and statistical generalization |

| Sample | Single case. |

| Evidence-gathering methods | Documentary review (documentation and archives). Multiple semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions. Use of physical, technological, and culture artefacts. |

| Information sources | Internal:

|

| Key informants | 12 senior managers and founders from several stakeholders. |

| Methods of analysing the evidence | Essentially qualitative:

|

| Scientific approach | Analytical induction through replication logic (analytical generalization). |

| Evaluation of the methodological rigor and quality | Validity (constructive, internal, and external), reliability, consistency (contextual and theoretical – interpretative). |

| Data conducted | October 2022–November 2023 |

After defining the unit of analysis, we conducted a screening within Spain and identified five EEs in major cities, each with distinct characteristics. Barcelona, with its 20-year commitment to 22@ Barcelona and its highly successful founders, is largely organised through Pier 01 Barcelona Tech City, with significant private influence. Madrid stands out as the capital of Spain with the presence of large corporations. Valencia, anchored by Lanzadera—a philanthropic accelerator established in 2013 by Juan Roig, founder of the nation's renowned supermarket chain Mercadona—and supported by other players such as Go Hub, Plug and Play, Innsomnia, and Demium, has developed an innovation district in the Marina. Málaga focuses on public initiatives to attract digital talent, while Bilbao features the BSB initiative created by the PCB.

After assessing the opportunity to explore a novel combination of public policies and the willingness of managers from different stakeholders to commit to this research, we chose to analyse the BSB.

Data collection and analysisConcerning data collection, we utilised methodological triangulation by employing multiple perspectives to converge on the phenomenon and validate the data. Between October 2022 and November 2023, we gathered evidence through reviews of internal and external documentation, conducted multiple in-depth interviews with key informants, and used physical, technological, and cultural artefacts to record interviews and produce photographs (Yin, 2017).

The interviews followed semi-structured, open-ended guidelines, adopting the form of guided conversations rather than structured queries. In these discussions, we aimed to address the following questions, among others:

- •

What was the origin of the BSB initiative?

- •

What was the process followed for its design and subsequent implementation?

- •

What does this initiative entail?

- •

How does it contribute to the creation of new ventures?

- •

What has been the social impact of the BSB?

We conducted nine formal individual or in-pair interviews with 12 informants; eight were conducted face-to-face, and one was conducted via Microsoft Teams. All interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min, were recorded using an MP4 recorder, and were then transcribed verbatim. Additionally, we maintained an ongoing dialogue with our main contacts to review or clarify any doubts or potential misunderstandings, using video conferences, telephone calls, and emails. Table 3 presents the number of interviews conducted for each stakeholder category. The interviews are listed as I1–I12, with no differentiation between the interviewee subgroups to maintain anonymity. The finite number of BSB EE actors allowed us to draw conclusions easily. The numbering does not follow a specific order.

Furthermore, we had the opportunity for a full immersion in the BSB, during which we obtained additional background information that significantly enriched the social context of the case study. This immersion provided us with a valuable understanding of various aspects related to the physical environment, including the location, common area, meeting rooms, and canteen at the BSB.

Regarding data analysis, the initial stage involved structuring the data according to a preliminary coding list established ex ante, based on a review of the existing literature (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The dimensions considered in this process were: (i) entrepreneurial culture – community; (ii) funding and investment, coordination of founders, business angels, and Venture Capital; (iii) public policies to promote entrepreneurship, focusing on financing, subsidies, and taxation; (iv) talent attraction and education; and (v) corporations and their participation in the BSB.

The interview transcripts were carefully reviewed on multiple occasions to discern and apply suitable codes. The coding list was subsequently refined, adapted, and detailed. The final coding analysis was conducted independently by two distinct researchers to bolster reliability, following the approach outlined by Eisenhardt (1989). Any variances in data interpretation and codes were deliberated until a consensus was reached between the two researchers.

In the second stage, the data were classified according to the five aforementioned dimensions, allowing for a specific analysis of the sample. A detailed analysis of the evidence was performed by applying the qualitative analytical tool Atlas.ti 9 to the data from the nine interviews and the reviews of internal and external documentation (Friese, 2011). To identify the patterns and relationships between the dimensions, a thematic search was conducted using the following keywords: economic development, talent attraction and retention, multicorporate, taxation, knowledge sharing, innovation, entrepreneurship, Open Innovation, and locality.

Entrepreneurial activities in the Basque CountryThe Basque CountryThe Basque Country is an autonomous region with approximately 2.2 million people located on Spain's northern coast, bordering France. Its GDP per capita ranks in the top 10 % of EU regions, and it has one of the lowest poverty rates. The region's robust industrial sector accounts for 23 % of its GDP, and its unemployment rate (8.3 %) was below Spain's national average (11.8 %) in 2020 (FitchRatins, 2023).

According to the Basque Government's Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report, GEM Basque Country (Saiz-Santos et al., 2023), the region hosts more than 1000 startups employing over 8000 people, with an estimated valuation exceeding EUR 1500 million. This ecosystem is closely intertwined with its manufacturing sector, where seven out of 10 startups develop solutions for the Basque Country's strategic sectors.

Concerning employment, technology-based and/or innovative companies created in recent years employed an average of eight workers per company and achieved a turnover exceeding EUR 750 million in 2021. Moreover, the startup survival rate is strong, exceeding 80 %.

Regarding investments, notable growth is observed in the number of active funds in the region, boasting more than 130 active investment stakeholders, both public and private. The report highlighted sustained growth in both the number and total amount of investment rounds. Over the past two years, more than EUR 198 million has been mobilised across 300 investment rounds, with 70 % coming from regional or state investment funds and 30 % from European investment funds.

The report underscores the ecosystem's unique public support, where a network of over 100 public and private stakeholders collaborates to create an optimal environment for launching, developing, and growing innovative and/or technology-based businesses. This is substantiated by the fact that, in 2022, Basque public and private stakeholders provided nearly 800 support programmes, initiatives, and tools for entrepreneurship at all stages and types, representing a total budget of more than EUR 96 million.

Bizkaia contextBizkaia is the largest of the three Historical Territories of the Basque Country, with its capital in Bilbao. At the turn of the 20th century, Bizkaia was an economic and financial hub in Europe, experiencing growth driven by shipbuilding and steel mills, and housing one of the busiest ports on the continent. Bizkaia has successfully transformed from an industrial-based territory into an international reference point for business and tourism without losing sight of its roots (Startup Genome, 2023).

From an economic perspective, the Basque Country, particularly Bizkaia, ranks among the most industrial and innovative regions in Europe, with innovation performance surpassing the EU-27 average (109.8 %). The Basque Country leads the national rankings and is recognised as a "hub of excellence", a highly innovative region within a country classified as having a moderate level of innovation. Its primary strengths lie in the advanced qualifications of its young population, the substantial impact of innovation on sales of new products, and the high percentage of individuals engaged in lifelong learning. This distinction is shared by Madrid in Spain, Prague in the Czech Republic, Athens and Crete in Greece, and Emilia-Romagna in Italy. Euskadi ranks 72 out of the 239 innovative European regions analysed (Hollanders & Es-Sadki, 2023).

Bizkaia has a diverse economy, with services constituting 73 % of its GDP. Industry, construction, and agriculture contribute 20 %, 6 %, and 1 %, respectively. This balanced distribution reflects the province's economic stability and development (Franco & Wilson, 2022).

Both Euskadi and Bizkaia are known for their industrial structure, particularly in the energy sector. Prominent companies in the region include Iberdrola, which ranks as the second-largest market capitalisation on the Ibex and the third-largest utility globally. Petronor, a subsidiary of Repsol with approximately 86 % ownership and a 14 % stake held by Kutxabank, leads the Basque Hydrogen Corridor (BH2C) and plays a key role in the entire energy sector value chain.

In the realm of mobility, Gipuzkoa features two major Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs), Irizar and CAF, while Bizkaia is home to global Tier 1 and Tier 2 companies such as Gestamp, CIE, and Maier. Finally, thanks to its Industry 4.0 business framework, Bizkaia excels in sectors where it acts as a model and is able to compete globally with any ecosystem.

Case results and discussionIn this section, we describe the decision-making process followed by the PCB to create the BSB EE that arose in the case study. Subsequently, our focus shifts to the implemented model as it emerged from the interviews.

The starting pointBased on the industrial and technological structures described in Section "Bizkaia context", the PCB team decided to invest in creating and developing an EE in the capital city of Bilbao.

"To achieve this goal, in 2017, we conducted fieldwork, including a global benchmarking study on entrepreneurial ecosystems across various defining areas… Specifically, given the unique jurisdiction of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia, at the fiscal level, we analysed implemented fiscal measures in London that led to the development of an entire fintech ecosystem. In addition, we explored Amsterdam for the role played by the Department of Finance in attracting investment to the country, recognising the importance of the tax ruling" (I2, I3).

Next, they focused their analysis on the dimension of entrepreneurial culture within an EE. In this study, four ecosystems—Boston, Tel Aviv, Barcelona, and Helsinki—were examined. Below are comments on the ecosystems of Boston and Tel Aviv.

"The business ecosystem in Boston is built on four pillars: an organised ecosystem involving all stakeholders; significant universities such as MIT and Harvard, where top-tier technical performance combines with entrepreneurship, and students are surrounded by individuals who have started companies and secured funding; broad access to the talent necessary for founding a company, as well as resources (lawyers, advisers, mentors) familiar with the startup world; and finally, access to capital, with investors well-versed in the startup scene actively participating in the boards of new companies (Smart capital)…

… Regarding the Tel Aviv ecosystem, we draw several lessons. The most important one is the significant role of public policies in the creation of the so-called Startup Nation, with initiatives including the establishment of the Office of the Chief Scientist in 1968 to aid in the commercialisation of advanced technology; the launch of the Business Incubator Programme in the 1990s; and the Yozma initiative to generate a venture capital industry in Israel, along with a specific programme to attract foreign researchers to the country" (I2).

At the incubator and accelerator levels, engagement with those deemed most relevant provided insights into how to structure an international entrepreneur centre, the value-added services provided by accelerators, and the process of building a community. The following international entrepreneurship centres were analysed:

"Cambridge Innovation Center (CIC) is one of the prominent incubators in the USA. Linked to MIT, CIC was founded in 1999 by Tim Rowe with the goal of fostering an EE. Beyond serving as an incubator, what sets CIC apart is its emphasis on ecosystem and community-building. Since its inception, CIC has raised over 3 billion in venture capital and has generated more than 40,000 jobs. They have also pioneered the non-profit Venture Coffee, featuring programmes like Captains of Innovation to connect startups with corporations…

… SOSA, which describes itself as a combined incubator-accelerator, connects early-stage technological startups with key partners in the ecosystem, including major corporations and investors, providing robust mentoring. Comprising the most influential venture capitalist in the Tel Aviv ecosystem, with two locations in Tel Aviv and a recently established one in New York…

… Talent Garden, originating in Italy, is a coworking centre network with a strong presence across Europe, particularly in Southern Europe. It fosters community by providing startups access to its locations and places a significant emphasis on training, catering to both startups and corporations…

…Station F is positioned as the premier incubator for corporates. A concerted public effort aims to establish it as the new European tech hub and the largest startup campus in Europe. Spanning 34,000 m2, it is in a former railway station in Paris, housing major French companies such as LMHV, Thales, TF1, HEC, among others. These companies leverage Station F for their Open Innovation initiatives and acceleration programmes. Additionally, it boasts an intriguing housing policy to accommodate entrepreneurs" (I2).

Finally, the programmes of the following four accelerators were analysed: Techstars, Plug and Play Tech Center, Y Combinator, and Dreamit Ventures.

After conducting this benchmarking, along with evaluations involving other key stakeholders, the conclusion reached was both simple and intricate: "every EE must build upon its strengths. This realisation laid the foundation for the design and implementation of the Biscay Startup Bay strategy" (I2, I3).

Biscay startup bay entrepreneurial ecosystem frameworkThe main strengths of the BSB are:

- •

Decisive political drive: Unlike other hubs that rely on private, philanthropic, or university involvement, following the American model, "in our case, it was the Head of the Provincial Council himself who led the project" (I2). Therefore, various public agencies have focused on entrepreneurship and innovation, including the economic development agency (BEAZ), the agency dedicated to attracting and retaining talent (Bizkaia Talent), and the public venture capital fund (Seed Capital), all aligned with this strategy.

- •

Multicorporate: As mentioned above, the Basque Country, and Bizkaia in particular, is characterised by a large number of multinational companies headquartered in the region. These companies operate in specific sectors such as Energy, Mobility, and Industry 4.0. "An example of this is that 20 % of our GDP belongs to the industrial sector, and nearly 20 % of employment is in the same sector. This proximity and closeness to the industry allow for effective collaboration" (I4).

- •

Taxation: The Basque Country and Bizkaia are unique cases in Europe, and "I would venture to say, globally. While not being a state, it has normative capacity over direct and indirect taxation. This grants the region the ability to have a tax capacity to influence key strategic areas" (I11). In this case, an Entrepreneurship Tax Statute was implemented.

Once these strengths were described, a framework was designed consisting of four pillars that characterised the uniqueness of the BSB EE: concentration, connectivity, multicorporate, and taxation, as shown in Fig. 1.

ConcentrationEvery EE needs a physical infrastructure, a "lighthouse" where local and foreign startups, corporations, and investors can converge. This hub facilitates cross-pollination among players from different ecosystems and is ideal for soft landings.

The selection of the International Entrepreneurship Centre's location was crucial. After analysing other global centres, such as those in downtown areas of cities like Boston and Tel Aviv, "we aimed for iconic and well-connected places, easily accessible by walking, biking, or public transportation. Additionally, they should be vibrant even after working hours" (I1).

After considering various buildings in Bilbao, the former BBVA headquarters in Plaza Circular was identified as meeting all the requirements. This 19-floor building, centrally located with the first five floors occupied by Primark, was leased from the sixth to the 19th floors by the PCB. This location, steeped in the history of being one of the leading banks in the region, became the site for the development of the International Entrepreneurship Centre in Torre Bizkaia, also known as the Biscay Accelerator Tower (BAT).

The BAT is not managed by public entities but by a globally recognised operator. A global public tender in 2020 led to the selection of a joint venture between PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and Talent Garden to manage the BAT.

The project was divided into three phases. The first phase, covering floors six to nine (4400 m2), opened in September 2022. Subsequent phases involved occupying an additional 4000 m2 from the 10th to the 14th floor, along with two more floors, the 15th and 16th, covering 1500 m2.

Given that the community is central to the OI framework, the primary goal of the centre is community-building. It offers flexible coworking spaces, private offices, meeting rooms, and 24/7 services. It also provides access to shared spaces and associated services, such as reception, business resources, tech support, fiscal domiciliation, fast tracking, and mentoring.

Aligned with its community-building goal, the centre focuses on six pillars: (i) Technological Innovation, fostering technological and innovative talent in the region; (ii) International Ecosystem, leveraging the PwC and Talent Garden network for access to other operator centres and priority hubs; (iii) Value-Added Services, providing advisory services for innovation plans, access to affiliated agents, and enhanced funding models; (iv) Physical Space, as previously discussed; (v) Sectoral Focus in three main vertical sectors (energy, mobility, and foodtech) and one transversal sector (Industry 4.0); and (vi) Public Support.

"The BAT aims to be more than just physical infrastructure, creating a space where startups, corporations, investors, and the university coexist, organising over 100 events annually to connect people, ideas, and projects. Activities include investor sessions, webinars, streaming events, Innovation Week, Investors Days with other affiliated ecosystems, community breakfasts, morning talks, sector-specific events, and after-work gatherings" (I1, I5, I6, I7, I8, I12).

ConnectivityAs revealed through benchmarking, "our ecosystem was conceived with a core emphasis on connectivity. Bilbao, while not a Tier 1 city like Barcelona or Paris, recognises the significance of being well-connected. Learning from global ecosystems in Tel Aviv, Boston, Austin, and Helsinki, we continue to organise internships in these locations for startups within our ecosystem. These initiatives not only provide attractive deal flows for our local corporates, but also serve as ideal environments for our startups to accelerate" (I1, I2).

Furthermore, "we have established connections with nodes in Latin America (Tec de Monterrey, Chile, Bogota), Singapore, and Japan. Our tax-friendly environment and public funding opportunities position BSB as a platform for soft landing and R&D activities for companies from these regions" (I2). To attract startups and corporations from outside the Basque Country, "we have structured and packaged existing subsidy lines in the Provincial Council for those deciding to develop their projects or R&D units in Bizkaia" (I3).

Collaboration with the operator, a joint venture between PwC and Talent Garden, allows startups and corporations in the BAT to access all their centres based on their interests.

Maintaining alliances with major players is crucial for the internationalisation and visibility of the BSB EE. Collaborations with Techstars and the South Summit involve events to energise the local ecosystem with international players.

MulticorporateAs highlighted earlier, one of the distinctive features of the BSB is the significant number and quality of corporations in the region, contributing to 20 % of GDP and employment. This region excels in three global verticals:

- •

Energy: This consists of two major companies: Iberdrola (the third-largest utility in the world) and Petronor (a leader within the Repsol group). Additionally, energy companies such as ABB and Schneider contribute to more than 30 % of Bizkaia's revenue and over 15,500 direct jobs.

- •

Mobility: Although lacking major OEM in this vertical, Bizkaia has significant Tier 1 and 2 companies such as Gestamp, CIE, Maier, and the MCC group.

- •

Industry 4.0: Given the industrial structure of the region, digitalisation is a key focus and differentiating vector.

Inspired by the experiences of the Boston and Tel Aviv ecosystems regarding how corporations collaborate with startups under OI principles, missions were organised with corporations in these ecosystems to understand and encourage OI collaborations. Moreover, as with PCB, "we decided to join the European Open Innovation Forum, led by Henry Chesbrough, to learn from the best and the pioneer of Open Innovation. In fact, we have implemented some of the network's recommendations and Chesbrough has visited Bizkaia twice to sensitise our corporations" (I2, I3, I8).

Following these best practices and differentiating itself from other ecosystems, one of the objectives of the BSB strategy is to avoid creating silos among corporations, steer clear of vertical collaborations, and promote horizontal collaborations. That is, fostering interactions not only Outside–In but also from the Inside–Out. Following Chesbrough's (2003) funnel model, the BSB EE aims to encourage corporations to share projects and patents.

To incentivise the Outside–In strategy from a public funding perspective, a fast track was established with their venture capital fund, Seed Capital. Through another PCB grant programme, "we finance innovation plans of corporations to aid in sensitisation and work on Open Innovation. We are also collaborating with Corporate Venture Capital from various corporations in the ecosystem to accelerate their deal flow in the territory. Furthermore, we are encouraging the possibility for local corporations to participate or establish acceleration programmes. In collaboration, if an accelerator invests in a startup, the start fund, linked to Seed Capital, is established to match, in a participatory loan model (with a two-year grace period), the investment made by the accelerator up to a maximum of 100,000 euros" (I3).

This strategy emphasises horizontal collaboration among corporations, avoids silos, and encourages collaboration across sectors.

A unique aspect of the BAT's development is that it is structured using specific scale-ups.

- •

Global smart grid hub, led by Iberdrola, concentrates all of the company's global knowledge on Smart Grids. It is equipped with cutting-edge technological infrastructure in which present-day and projected group suppliers, as well as startups, come together. The connection with the BAT is complete, as not only is Iberdrola one of the BAT's members but startups under its orbit are located in both locations.

- •

European Innovation Council (EIC) hydrogen, is a new scale-up initiative focused on the hydrogen sector, led by Petronor. The building features technological infrastructure designed for user utilisation.

- •

Automotive Intelligence Centre (AIC) was inaugurated in 2007 and focuses on addressing the challenges of mobility in technological infrastructure and academia.

The entire ecosystem is integrated, breaking down silos and encouraging collaboration between startups and corporations. As one corporation stated, "our company has a powerful tractor effect that helps startups in several manners: firstly, by advancing financing, without repayment guarantee, in the initial phase of product development, supported by the 64bis tax article; secondly, by working with our technicians to develop a new product under the specifications provided by us in order to respond to our needs in smart grids; and finally, the most important one, to become a qualified supplier of our company" (I8, I9).

TaxationThe PCB, empowered by the Historical Territory law and its rich traditions, has the authority to collect and manage all taxes in its territory, except customs duties, mirroring the fiscal autonomy of a state. "Internationally, this autonomy became a pivotal and distinctive aspect, drawing inspiration from the fintech ecosystem model of London. This model was instrumental in fostering innovation and entrepreneurship, particularly in the financial sector" (I3).

Bizkaia's taxation is notable for its clarity; the Treasury provides binding responses to inquiries and maintains an approachable demeanour, largely facilitated by the manageable dimensions of the territory. To prevent double taxation, agreements are in place, and it prides itself on being a transparent fiscal authority.

Historically, Bizkaia has demonstrated a commitment to R&D, with deductions reaching up to 70 % of the quota, incentivising the hiring of research staff and featuring a patent box. In total, deductions could reach 80.5 % of the quota, factoring in a limit of 70 % applied after subtracting those capped at 35 %. Recognising the need for more, an entrepreneurship tax statute was developed with a comprehensive 360° vision covering all stakeholders in the EE, including founders, workers with equity or phantom shares, corporations, alternative financing entities, venture capital, private equity, talent, and investors.

During the investment phase, founders are granted a 35 % deduction in personal income tax if they invest in technology companies (within the first seven years of the company's life), with a limit equivalent to 20 % of their personal income tax base for the year. If the limit is exceeded, the excess can be applied in the subsequent five years. Another 35 % deduction applies to investments in capital expansion for new products or markets. No wealth tax is levied on equity held during the investment period. Upon exit, a 50 % exemption on capital gains results in an effective tax rate of 12.5 %. If startups, technology companies, or innovative projects are reinvested in the next two years, the exemption increases to 100 %. Additionally, a Loss Compensation System has been established to offset failed investments against other investor incomes, following a successful model implemented in London to incentivise the fintech industry.

Workers with equity receive similar treatment to that of founders. However, no tax is imposed on phantom shares or similar rights, which are common in startups. At the time of exit, payments ranging from 20 % to 25 % are made, but only at that moment.

For both foreign workers and Spaniards who have resided abroad for more than five years, a unique regulation has been established in personal income tax. For over 11 years, a 30 % exemption from personal income tax on salaries was granted. An additional exemption of up to 20 % is provided for relocation expenses, including rent, supplies, schools, travel (twice a year for the entire family), and moving expenses. Furthermore, an exemption from wealth tax applies to gains from foreign-owned capital assets, extending to spouses, cohabiting partners, and family members.

"The emphasis on corporations as a differentiating foundation of the ecosystem is reflected in fiscal incentives. At the time of investment, a deduction of up to 35 % is granted for investments in innovative companies, with a limit equivalent to the deduction base of 25 % of capital and 35 % of tax. Excess deductions can be applied over the next 30 years. A 65 % reduction in the tax base is facilitated with a special reserve for promoting entrepreneurship and reinforcing productive activity. No taxes are paid on exit gains, and a Loss Compensation System is established to offset losses from failed investments against other investor income (profits from other businesses, other income, etc.)" (I3).

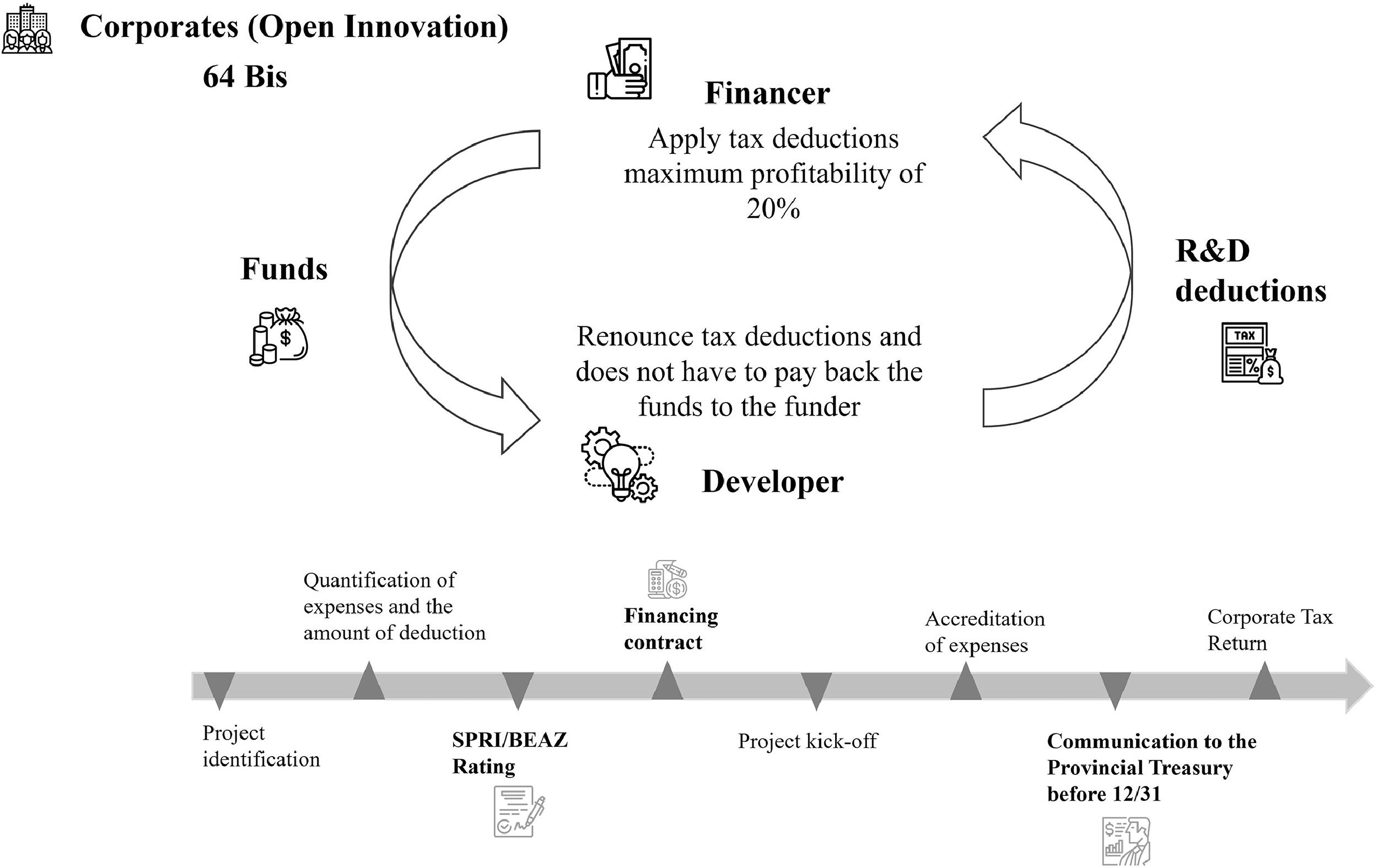

An innovative secondary market, driven by the so-called 64bis system (Fig. 2), allows R&D-intensive companies, primarily startups, to sell R&D tax credits to corporations paying corporate income taxes. Under the legal security provided by the economic development agency (BEAZ), corporations purchase tax credits at a 20 % discount, yielding a 120 % return on milestones at the start of the startup's R&D project.

The fiscal incentive policy for R&D remains robust, offering deductions of 10 % for investments in non-current assets between 30 % and 50 % for R&D activities, and between 15 % and 20 % for technological innovation. Additionally, job creation allows for a 25 % deduction in the annual gross salary, capped at 50 % of the minimum wage. Investments and expenses associated with sustainable development, conservation, environmental improvement, and the use of more efficient energy sources receive a 30 % deduction.

To encourage early-stage investments, especially from angel investors, family members, and friends, a specific fiscal incentive policy was established. This includes a 35 % deduction in personal income tax for investments in technology companies made within the first seven years of the company's life, with a limit equivalent to 20 % of the personal income tax base for the year. If the deduction exceeds this limit, the excess can be applied in the following five years. An additional 35 % deduction is granted for investments in capital expansion for new products or markets. No wealth tax is paid during the investment period, and upon exit, a 50 % exemption from capital gains results in an effective tax rate of 12.5 %. If startups, technology companies, or innovative projects are reinvested in the next two years, 100 % of the gains are exempt. Additionally, a Loss Compensation System was established for failed investments, allowing investors to offset losses against other income, such as salary or dividends.

For Venture Capital vehicles, returns derived from participation, shares, or other rights granting special economic rights are considered work income. They are integrated into the taxable base at 50 %, resulting in a maximum effective tax rate of 24.5 %. Therefore, the carried interest is taxed at 24.5 %.

In summary, Bizkaia has pioneered a comprehensive entrepreneurship tax statute, setting it apart from other European ecosystems.

Conclusions and implicationsIn this section, we describe the contributions of our study to the literature on the creation, development, and consolidation of a regional EE, with a special emphasis on the public policies developed and how they have encouraged OI collaborations between corporations and startups, as well as among corporations. The implications for policymakers, along with a discussion of the limitations and avenues for future research, conclude this study.

Theoretical contributionsOur research offers five key theoretical contributions. First, we demonstrate a shift from analysing individual entrepreneurship to examining the complex network of relationships within EEs. This shift is significant for both policymakers and researchers.

Second, our research describes a novel EE framework. This framework aligns with Isenberg's (2011) characteristics of a self-sustaining EE and encompasses six domains: policy, markets, capital, human skills, culture, and support. The BSB EE framework does not include explicit causal pathways, reflecting the "high bandwidth nature" of policy, as described by Hausmann (2008). Effective policy must consider multiple variables that interact in complex and specific ways. For example, providing support to entrepreneurs in the form of space, capital, or loans is meaningful only if established companies (e.g., large corporations) and governments are willing to engage startups as potential suppliers. This underscores the need for policymakers to intervene holistically and adopt a comprehensive ecosystem perspective.

Third, building upon the BSB EE framework that highlights the importance of policy within EEs, our research contributes to the nascent OI policy literature (Bogers et al., 2018; Di Minin & Cricchio, 2024). We demonstrate how OI practices fostered by regional governments can be implemented to develop a regional EE.

Fourth, our research expands the understanding of OI by analysing it at the inter-organisational network level within an EE, moving beyond the traditional focus on large firms (Chesbrough, 2003). This approach reveals how OI can support new ventures not only in achieving financial success but also in scaling their social and environmental impacts (Weissenböck & Gruber, 2024). Effectively managing an EE is crucial in this context, as OI extends beyond the bilateral insourcing of externally developed technologies. Organisations must actively identify strategic partners, nurture the ecosystem, minimise tensions between collaborators, and foster a shared vision. EEs provide a robust structure for inter-firm relations, facilitating collaboration while also potentially constraining individual interactions between specific companies.

Finally, our research demonstrates how the adoption of OI practices within the BBS contributed to achieving the four key features of a successful EE as outlined by Xu and Dobson (2019). These features were realised by establishing a dedicated physical space (BAT) that fostered a vibrant innovation community. Stakeholders within this space actively participate in the innovation process, acting as both contributors (generating new knowledge and innovations) and recipients (utilising knowledge to develop innovations). This dynamic exchange aligns with the theory of absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), which posits that such interactions facilitate the productive exchange of highly specialised information.

Practical implicationsA crucial implication for policymakers is the need to shift from simply providing support to actively creating and nurturing an EE. This requires a proactive approach, including a critical review of existing policies and decisive actions to address shortcomings. Public agencies should identify and rectify policy mistakes, such as underprioritising public support or unintentionally discouraging entrepreneurial finance providers (Isenberg, 2011). This proactive approach is exemplified by the Basque Country, where the pivotal support of the PCB, along with BEAZ, Bizkaia Talent, and Seed Capital, forms the cornerstone of the BSB EE, complemented by a pioneering comprehensive tax statute for entrepreneurs.

The BSB EE offers a unique advantage by connecting startups with early customers (large corporations). This interaction benefits both parties. Startups gain valuable insights from established players, allowing them to refine their products or services and secure crucial references. Importantly, the revenue generated from these early customers acts as a particularly favourable form of financing for young ventures.

Furthermore, this collaboration fosters a win-win situation. Startups retain ownership of their intellectual property, while large corporations gain a first-mover advantage by being the first to introduce innovative products to the market, potentially influencing industry standards. This model of corporate engagement aligns with the strategic goals of both startups and large corporations, as their activities, resources, and motives often complement each other (Gutmann, 2023; Jha et al., 2024). This exemplifies how Outside-Out OI knowledge flows can contribute to shaping a thriving EE (Gutmann et al., 2023).

Limitations and suggestions for future researchRegarding the limitations of this study, while the single-case study methodology used was appropriate for researching the phenomenon, it has several constraints related to sample selection, geographical scope, and the time required for longitudinal research, especially concerning statistical generalisation. Additionally, single-case studies offer fewer opportunities to employ Yin's replication logic for verification compared to multiple case studies (Yin, 2017).

Given these limitations, future research should consider employing a multiple-case study approach to analyse other Spanish EEs. This would allow for the identification and comparison of similarities and differences between these EEs and the BSB EE. By examining a broader range of cases, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing EE creation, development, and consolidation, as well as their impacts on regional economic growth.

Additionally, further research is needed to explore how heterogeneity and cognitive distance (Nooteboom et al., 2007) among EE stakeholders influence knowledge creation dynamics and innovation output. Investigating these factors can provide valuable insights into the optimal composition and management of EEs to maximise their effectiveness in fostering innovation.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJuan R. Campos-Blázquez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Sandra Martín-García: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Mar Cárdenas-Muñoz: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis.

The authors greatly appreciate the contributions of Iñaki Alonso Arce and Koldo Atxutegi Ajuria and all the professionals from the different actors belonged to the Biscay Startup Bay entrepreneurial ecosystem who have contributed to this research for their support and generosity. All error and omissions remain ours.