This study distinguishes itself from existing organizational culture studies by investigating the relatively under-studied theoretical relationship between organizational culture and employer attractiveness. To capture the holistic nature of organizational culture theory, this study adopts configurational analysis, which contrasts resourceful cultural attributes (collaborative, employee development, and fair-compensation cultures) with demanding attributes (result-oriented, overworked, and job-insecurity cultures). This study proposes three configurational propositions of employer attractiveness and employs review-based topic modeling and fuzzy-set quality comparative analysis (fsQCA) to overcome the limitations of traditional survey-based measurement and regression analysis. For the empirical analysis, this study constructs an industry-wide dataset comprising 2209 quarterly samples from 157 hotels over six years, utilizing 54,889 employee reviews posted on Glassdoor in the United States. Topic modeling analysis adopting Latent Dirichlet Allocation extracts the probabilities of six cultural attributes. Finally, the fsQCA generates three groups of 13 configurations, leading to employer attractiveness: a fully resourced culture, a resourced and low-demanding culture, and a fairly compensated overwork culture. The findings confirm the core concepts of configurational analysis in contrast to regression analysis and present novel theoretical, methodological, and practical implications.

The success of organizations is heavily dependent not only on product and service market performance to win customers but also on the competitiveness of the labor market to attract competent employees (Gehrels & de Looij, 2011; Theurer et al., 2018). Thus, enhancing employer attractiveness and improving employer branding are essential strategic approaches to enhance the loyalty of current employees and attract prospective employees (Gehrels & de Looij, 2011; Lee & Choi, 2022; Srivastava & Bhatnagar, 2010; Theurer et al., 2018). Employer attractiveness refers to the benefits and values that both current and prospective employees perceive in a specific organization (Gehrels & de Looij, 2011; Lee & Choi, 2022; Theurer et al., 2018).

This study focuses on organizational culture as a critical predictor of employer attractiveness. Organizational culture studies have long investigated the impact of cultural attributes on internal organizational members to explain organizational effectiveness, performance, and competitiveness (Hober et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2023; Naveed et al., 2022; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983; Schein, 1990; Schulte et al., 2009; Velasco Vizcaíno et al., 2021). By exploring a relatively unearthed theoretical relationship, we propose that organizational culture can play a critical role in developing and maintaining an organization's attractiveness as an employer in the external labor market (Catanzaro et al., 2010; Lee & Choi, 2022; Sommer et al., 2017).

The hotel industry faces tremendous challenges owing to a shortage of skilled workers and a high turnover rate. Therefore, acquiring talent and retaining fully motivated employees are important success factors for hotels (Gehrels & de Looij, 2011; Lee & Choi, 2022). According to a survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the United States (US), the turnover rate in the hospitality sector increased significantly from 66.7 % in 2014 to 78.9 % in 2019, although the national average turnover rate in 2019 was 36.4 % (Lee & Choi, 2022). A problematic aspect of labor market competition for hotel firms is that it is arduous to differentiate themselves from competitors as attractive employers because jobs within the same hotel industry are largely similar (Lee & Choi, 2022; Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). Given these issues, understanding hotels’ attractiveness as employers is critical for building the most qualified applicant pool.

To elucidate hotels’ employer attractiveness, we investigated organizational culture's role in determining recruitment performance and applicants’ job acceptance. Beyond existing perspectives that highlight the impact of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness and performance, our study adds to the theoretical position that an attractive organizational culture can appeal to talented employees, encourage applicants to accept a job, and positively influence their tenure once hired (Catanzaro et al., 2010; Lee & Choi, 2022; Sommer et al., 2017). Furthermore, to investigate organizational culture, we adopted a configurational analysis of culture to materialize the theoretical potential of the holistic characteristics of organizational culture. The configurational analysis in this study intensifies our understanding of the complex combinational impacts of diverging cultural attributes, overcoming the limitations of a variable-centered approach using regression analysis of specific cultural attributes (Jung et al., 2009; Marinova et al., 2019; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Schulte et al., 2009). This study assumes complex combinations of resourceful (collaborative, employee development, and fair-compensation culture) and demanding (result-oriented, overwork, and job-insecurity culture) attributes of organizational culture and presents three configurational propositions for hotel employer attractiveness (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Lee & Choi, 2023, 2024).

In addition to the distinctive theoretical perspectives, we adopted a novel combination of methodological approaches. We performed review-based topic modeling and fuzzy-set quality comparative analysis (fsQCA) of organizational culture, overcoming the limitations of traditional survey-based measurement and regression analyses in the existing literature. In previous studies on organizational culture, a variable-centered approach performed a regression analysis of specific cultural attributes using self-reported employee surveys in a limited number of organizations (Lee & Choi, 2022; Marinova et al., 2019; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). However, the existing methodological approach has numerous restrictions in fully materializing the theoretical potential of holistic organizational cultures. With its anthropological roots, the theory of organizational culture has adopted a holistic perspective from its early studies, suggesting that the combined patterns of cultural attributes cause different outcomes depending on how they are arranged (Fiss, 2007; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014).

To address these limitations, we employed fsQCA for the configuration analysis of organizational culture. fsQCA, utilizing set-theoretic analysis, enables researchers to identify sufficient or necessary conditions to explain outcomes and determine the relative importance of different combinations of conditions (Chen et al., 2023; Fiss, 2007; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). It provides a more fine-grained analysis for evaluating the importance of cultural dimensions in a configuration by distinguishing between core and peripheral dimensions (Fiss, 2007; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Pappas & Woodside, 2021).

Furthermore, our study used an industry-wide employee review of hotels posted on Glassdoor, one of the largest job search platforms in the US (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022; Sull, Turconi, & Sull, 2020), which overcame the limitations of individual self-reporting surveys in a small number of organizations (Denison et al., 2014). We prepared a sample dataset consisting of 54,889 employee reviews from 157 hotel firms and aggregated personal reviews to evaluate corporate-level organizational culture with minimum personal bias. To measure the diverse dimensions of organizational culture in industry-wide big data, we adopted Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a topic modeling software (Blei, 2012; Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018), which calculates the probability of topics for organizational culture. The theoretical relevance and validity of each topic were estimated using manual coding.

Exploring the relatively unearthed theoretical relationship between organizational culture and employer attractiveness, this study draws on a configurational analysis to actualize the theoretical potential of the holistic nature of organizational culture. To achieve this goal, we adopted a novel research methodology of review-based topic modeling and fsQCA for the US hotel industry. The analysis results not only explore new theoretical potentials of organizational culture but also present a comparative analysis between fsQCA's configurational analysis of holistic organizational culture and the regression analysis of individual attributes, generating novel methodological implications and practical insights for hotel employers.

Literature reviewOrganizational culture refers to the set of shared values, beliefs, norms, basic assumptions, and behaviors among organizational members that significantly influence how employees interact with each other and external stakeholders (Lee & Choi, 2022; 2023, 2024; Naveed et al., 2022; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983; Schein, 1990; Schulte et al., 2009). Focusing on different influences of diverse cultural attributes, researchers have long investigated how organizational culture affects critical organizational outcomes, such as organizational effectiveness, performance, and competitiveness (Hober et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2023; Lee & Choi, 2023, 2024; Naveed et al., 2022; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983; Schein, 1990; Schulte et al., 2009; Velasco Vizcaíno et al., 2021). Although existing literature primarily focuses on the cultural impact on internal members to explain critical organizational outcomes, it is crucial to recognize that distinctive cultural attributes can also send important signals to the external labor market, affecting an organization's attractiveness as an employer (Catanzaro et al., 2010; Lee & Choi, 2022; Sommer et al., 2017).

Recognizing this theoretical potential to extend to employer branding strategy, Sommer et al. (2017) conducted a scenario-based experiment in Germany. Their findings revealed that an innovative culture resonates more strongly with innovative individuals. Catanzaro et al. (2010) investigated gender differences in the context of competitive and supportive organizational cultures that affect job applicants. Based on the hypothetical organizations depicted in recruitment brochures in the US, most respondents were found to prefer working for a supportive organization. However, men were more inclined to pursue jobs in competitive cultures. Finally, Lee and Choi (2022) collected employee review data from hotel firms in the US, applied topic modeling analysis, and conducted a regression analysis. They reported that a set of positive organizational cultures, such as collaboration, employee development, fair-compensation, and customer focus, positively affect employer attractiveness. However, innovation culture has no significant effect. Despite the research efforts discussed above, studies on the impact of organizational culture on employer attractiveness remain theoretically and empirically limited.

Organizational culture possesses holistic and systematic characteristics as one of the most significant aspects. Organizational culture combines different and sometimes conflicting attributes within an organization, and each individual attribute should be regarded as part of the entire culture (Lee & Choi, 2022; Marinova et al., 2019; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). The holistic perspective emphasizes that each dimension of organizational culture should not be treated independently as they interact in a complex manner to generate essential outcomes (Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). Despite the significant theoretical potential of the holistic nature of organizational culture, regression analysis, which dominates existing studies, has numerous limitations in capturing causal complexity of organizational culture (Marinova et al., 2019; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Schulte et al., 2009). Given the holistic and systematic nature of organizational culture, the configurational approach used in our study can better fit the analysis of organizational culture than regression models, effectively intensifying our understanding of the relationship between the complex configurations of organizational culture and differential organizational outcomes (Marinova et al., 2019; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Schulte et al., 2009).

Configurational propositions of hotels’ employer attractivenessFocusing on analyzing the complex combinations and interactions of different cultural attributes in generating outcomes, configurational analysis emphasizes the equifinality of varying configurations, the synergistic effects of different attributes, and the nonlinearity of causation (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). The equifinality concept suggests that different configurations can generate the same final outcomes from different initial conditions and paths (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). The equifinality of organizational culture presumes that organizations can develop varying configurations of organizational culture with different sets of internal attributes to obtain the same outcomes. Synergistic interactions presume complex interactions between different attributes, suggesting that causally relevant outcomes result from the intersections between different forces and events (Misangyi et al., 2017). The nonlinearity of causation presumes that the cultural attributes that are causally associated in a configuration are not related or are even inversely related in different configurations (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). Furthermore, this suggests that the absence of any attribute, as much as its presence, can lead to an important outcome when combined with other attributes (Misangyi et al., 2017).

Organizational culture encompasses various cultural attributes simultaneously, although they often conflict with one another to meet complex environmental needs. Within a cultural configuration, different attributes interact in a complex manner to generate distinctive configurations that affect employer attractiveness. An effective configurational analysis of organizational culture begins by categorizing distinctive configurations and identifying different cultural attributes that are commonly relevant to the critical outcomes in question (Marinova et al., 2019; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Schulte et al., 2009).

As many hotels suffer from persistent problems, such as shortage of a skilled workforce and high turnover rate, employer attractiveness is a critical success factor for winning against competitors (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). Employer attractiveness refers to the envisioned benefits and values that current and prospective employees gain when they work for a specific organization (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). Strong employer attractiveness enhances the organizational commitment of current employees and effectively appeals to prospective employees (Gehrels & de Looij, 2011; Theurer et al., 2018). As organizational culture affects the development of employees’ dedication and commitment to an organization, varying configurations of organizational culture are strongly associated with the extent to which hotels are attractive to employees and applicants (Srivastava & Bhatnagar, 2010).

Resourceful and demanding attribute of organizational cultureOrganizational culture theory posits that different and conflicting cultural attributes coexist within an organization and that their complex combinations give rise to critical organizational outcomes (Marinova et al., 2019; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). Considering the diversity of organizational cultures and the causal complexity of their interactions, a taxonomy that classifies these attributes into categories related to employer attractiveness can significantly reduce the interpretative complexity of cultural interactions, thereby promoting a more intuitive understanding of their distinctive impacts. Furthermore, a classification that includes both positive and negative cultural attributes enables researchers to overcome potential bias from viewing only one side and adopt a more holistic and balanced perspective when analyzing the complex interactions of contrasting organizational cultures.

Regarding the taxonomy of organizational culture, Lee and Choi (2023, 2024) proposed a useful framework that distinguishes between the resourceful and demanding attributes of organizational culture based on the job demands-resources (JD-R) model. The JD-R model emphasizes the interactions between the resourceful and demanding aspects of the job to predict not only employees’ well-being and high performance but also their job stress and burnout (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Jang et al., 2017; Lee & Choi, 2023, 2024). Drawing on Lee and Choi's (2023, 2024) taxonomy, this study classifies cultural attributes into two categories: resourceful and demanding attributes of organizational culture. This study proposes that resourceful cultural attributes enhance employer attractiveness, whereas demanding attributes negatively affect it.

Resourceful attributes such as collaborative, employee development, and fair-compensation culture are strongly associated with employee satisfaction, well-being, and high performance, significantly improving hotel employer attractiveness (Lee & Choi, 2022, 2023, 2024). Collaborative culture in organizations highlights the sharing of a common vision and norms among employees. It considers employees as people (Tjosvold & Tsao, 1989), and promotes knowledge sharing and learning (Yang, 2007). In an employee development culture, employees are empowered to acquire new knowledge and skills to meet new job requirements (Hassan et al., 2006; Kuvaas & Dysvik, 2009). Fair-compensation culture in organizations upholds the norms of fairness, not only in the process of making decisions, but also in the results of distribution decisions, thus promoting employees’ continuous efforts to improve performances (Choi & Chen, 2007; Edgar et al., 2014; Namasivayam et al., 2007).

In contrast, demanding attributes such as result-oriented, overwork, and job-insecurity cultures create stressful and high-pressure working conditions, thereby negatively affecting employer attractiveness. By carefully monitoring employee efforts (Coget, 2010; Kohli et al., 1998) and creating strong inward pressure (Mitchell et al., 2019), the result-oriented culture stresses the achievement of end results through goal setting. The overwork culture requires employees to dedicate extra time to their work beyond the standard, agreed-upon hours, which may escalate various work risks (Ishaq et al., 2021; Mazzetti et al., 2016). Under the job-insecurity culture, employees perceive powerlessness to maintain jobs and have widespread concerns about job loss and career development risks (Låstad et al., 2015; Nikolova et al., 2018).

Configurational propositionThe equifinality concept of configurational analysis (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014) suggests that multiple cultural configurations combining both resourceful and demanding attributes may coexist to achieve the same organizational results of high employer attractiveness. As different sets of cultural attributes have synergetic interactions (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014), different configurations of cultural attributes may lead to identical results in enhancing employer attractiveness. Thus, hotels may develop different cultural attribute configurations and achieve the same outcomes to ensure employer attractiveness.

Proposition 1.The attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture has multiple sets of resourceful and demanding attributes as different combinations of the cultural attributes can lead to employer attractiveness.

The JD-R model suggests contrasting roles between resourceful and demanding attributes in employee commitment and organizational satisfaction (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Jang et al., 2017), directly affecting employer attractiveness (Jang et al., 2017). Resourceful attributes provide employees with social support, growth opportunities, and fair rewards to obtain high job satisfaction and performance. However, demanding attributes lead to burnout and turnover intention by increasing performance pressure, work overload, and job stability concerns. Thus, given the opposing effects, attractive configurations of organizational culture are likely to develop more resourceful than demanding attributes.

Proposition 2.The attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture encompasses more resourceful attributes than demanding attributes as the resourceful attributes positively contribute to employer attractiveness, whereas the demanding attributes negatively contribute to the attractiveness.

According to the competing value framework (Marinova et al., 2019; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983), organizational culture configurations may encompass contrasting attributes that work together to generate meaningful outcomes. Furthermore, configurational analysis involves the synergistic effects of different attributes as well as the nonlinearity of causation (Fiss, 2007; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). To be effective, organizations must be simultaneously concerned with contrasting values and norms. Furthermore, a growing body of paradox theory suggests that resolving paradox and working with contradictions are critical for organizational survival and high performance (Schad et al., 2016). To be competitive, organizations should achieve multiple goals while maintaining high congruence between conflicting cultural norms and values. Thus, an attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture can have both resourceful and demanding attributes that generate employer attractiveness.

Proposition 3.The attractive configurations of hotels’ organizational culture encompass conflicting attributes simultaneously as the congruence between the resourceful attributes and demanding attributes can generate employer attractiveness.

MethodologyDistinguishing itself from existing survey-based measurements and regression analyses, this study proposes a novel methodological strategy that collects employee review data from Glassdoor and performs topic modeling to measure organizational culture in review texts (Fig. 1). Topic modeling encompasses three phases: tokenization of text, generation of 100 LDA topics, and manual coding of topics. Based on the measurement data, this study conducted both correlation and regression analyses and configuration analysis using fsQCA, leading to a comparative discussion of the analysis results. The regression analysis assumes that the relationships are symmetrical and linear (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). It focuses on assessing the unique contribution of a cultural attribute while maintaining the influence of other cultural dimensions (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). With a symmetrical assumption, regression analysis aims to identify determinants that explain high levels of the outcome variable, assuming that the exact opposite will result in low levels of the same outcome (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Consequently, regression analysis encounters difficulties in accounting for potentially complex interactions among the different cultural attributes that operate as a system (Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Considering the differences in methodologies, we initially performed a regression analysis and then employed a configurational analysis using fsQCA, providing a comparative analysis between the two methodological approaches. The fsQCA process in our study consists of three phases: calibration, necessity and sufficiency analysis, and testing of the configurational proposition. A comparative analysis of the findings provided a crucial understanding of the methodological differences and hidden insights revealed by the configurational analysis.

Collecting employee review dataTo perform an empirical analysis, we tapped into the Glassdoor website in the US and collected reviews of hotel firms written by current and former employees. Glassdoor, one of the largest job search platforms in the US, has accumulated 55 million reviews of 900,000 organizations since 2008 and recorded 67 million unique monthly visitors in 2020. After authenticating identity, Glassdoor enables users to review anonymously and search for job post reviews to gain employment details (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022, 2023, 2024). This study combines all texts (both pros and cons) to identify employees’ diverse cultural attributes. Many existing studies of organizational culture rely on surveys of a few individuals in a firm, raising concerns of personal bias and limited validity (Denison et al., 2014; Lee & Choi, 2022; 2023; 2024). Reviews on the Glassdoor platform enable employees to provide free text responses about a firm's organizational culture and help researchers gain a more comprehensive picture of a firm's organizational culture than surveys (Sull, Turconi, & Sull, 2020).

To search for hotel firms on Glassdoor, we adopted a list of hotel brands and chains in the US from the Looking for Booking website and used not only the direct terms such as “hotel(s),” “motel(s),” “lodge(ing),” but also indirect terms such as “resort(s),” “vacation(s),” “casino(s),” “park(s),” and “hospitality” for the search process. Initially, 78, 563 employee reviews were collected from 189 hotel firms, with a minimum of 100 reviews published in November 2020. Considering that this study assessed organizational culture at the firm-level, it should have a sufficient number of employee reviews to evaluate cultural attributes appropriately (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022; 2023; 2024). Therefore, this study sets five reviews per quarter as the minimum requirement for the analysis. Furthermore, it restricts reviews written between January 2014 and December 2019 to avoid unusual business disturbances caused by COVID-19. After filtering and formatting the data, we constructed an industry-wide dataset encompassing 2209 quarterly samples from 157 hotels over six years, including 54,889 employee reviews.

Measurement by topic modeling analysisTo measure organizational culture from review texts, this study adopted the LDA topic modeling technology and assessed the probability distribution of cultural topics in quarterly reviews. As an unsupervised machine-learning tool, LDA topic modeling enables users to identify the hidden structure of documents by generating interpretable topic distributions in the documents (Blei, 2012; Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022, 2023, 2024; Maier et al., 2018). In the topic modeling process, LDA assumes a “bag of words” that ignores word orders in textual documents. LDA is designed to have a mixed-membership model of grouped data, where each group presents multiple topics in different proportions. The topic modeling identifies distinctive topics across the corpus in such a way that it collects words that frequently co-occur within each employee review. Subsequently, it generates a topic matrix that presents a probabilistic mixture of topics in each review by calculating the percentages across all the topics (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018).

To measure hotel firms’ organizational culture, we integrated the quarterly Glassdoor reviews of a firm and performed an LDA analysis that generated the probability of 100 cultural topics by adopting an unsupervised machine-learning process. Specifically, we conducted a three-step analysis (Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018). First, we performed basic and standard procedures for data cleaning and preprocessing of unstructured text. The cleaning process conducted text tokenization, such as discarding punctuations and word capitalizations, eliminating stop words, removing highly frequent and infrequent words, and performing stemming and/or lemmatizing (Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018).

Second, 100 LDA topics were generated. Choosing the number of LDA topics generated by machine-learning tools is a highly complicated task, because there is no standard procedure for calculating the appropriate number of topics (Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018). Users can freely set the number of topics in the LDA operation (e.g., 30, 50, 100, and 500). A dilemma that researchers may face is that generating a small number of broad topics creates the problem of obtaining general topics containing different themes, whereas generating many topics leads to overly specific and narrow topics (Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018). Rather than running the risk of missing critical cultural topics, we generated a relatively large number of 100 topics, which helped gain narrowly defined topics for manual identification of diverse cultural attributes.

Third, to identify cultural attributes in the LDA topics, we performed a manual coding process to estimate the theoretical relevance and validity of each topic (Table 1). Although unsupervised machine learning of LDA can generate multiple topics, it cannot offer the meaning of the topics and, thus, necessitates human interpretation to estimate the cultural relevance of the topics. The meanings of topics are not deterministic and must be evaluated based on substantive theoretical constructs (Lee & Choi, 2022; Maier et al., 2018). Thus, we adopted the most straightforward approach in which researchers read the terms in the model results, interpreted the meaning of topics, and matched them to cultural attributes (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2022; 2023; 2024; Maier et al., 2018). During the matching process, the three researchers independently read, interpreted, and selected topics relevant to the theoretical constructs of cultural attributes. After examining 100 topics with the 15 most frequent terms, one researcher proposed 35 topics, another 39 topics, and a third 44 topics.

Construct measurement by topics generated by LDA.

| Construct | Topic | Frequent term |

|---|---|---|

| Collaborative culture | 3 | friendly, environment, great, work, atmosphere, helpful, everyone, coworkers, team, worker, fun, sometimes, pleasant, relaxed, welcoming |

| 5 | work, love, great, amazing, people, really, intern, awesome, place, wish, enjoy, caring, hard, team, environment | |

| 8 | make, everyone, help, feel, like, thing, way, every, willing, know, same, think, something, just, else | |

| 9 | like, family, feel, stay, treat, part, friend, always just, well, number, come, definitely, enjoy, work | |

| 14 | work, environment, place, great, really, positive, fun, team, enjoy, hard, professional, tough, exciting, supportive, chance | |

| 16 | good, work, nice, people, far, coworker, bit, place, building, everything, load, area, definitely, heavy, generally | |

| 22 | work, great, place, good, home, excellent, colleague, well, smart, think, social, clear, condition, tight, add | |

| 33 | work, people, really, nice, get, hard, lot, time, super, cool, easy, fun, everyone, extremely, awesome | |

| 47 | staff, friendly, management, short, always, work, sometimes, busy, good, shift, colleague, hour, environment, finish, fairmont | |

| 51 | team, member, value, share, family, together, need, supportive, top, core, truly, well, part, wonderful, positive | |

| 53 | environment, work, fun, great, good, fast, friendly, paced, challenge, supportive, colleague, overall. beautiful, professional, win | |

| 64 | work, really, love, people, back, enjoy, face, help, everyone, laid, everyday, interact, able, community, appreciate | |

| Employee development culture | 13 | opportunity, room, advancement, growth, benefit, plenty, small, little, offer, compensation, pto, competitive, position, discounted, fulltime |

| 23 | company, opportunity, move, grow, growth, lot, willing, advance, city, career, offer, great, quickly, limit, limited | |

| 24 | opportunity, career, growth, grow, development, great, culture, learn, challenge, company, excellent, progression, leadership, path, compensation | |

| 41 | training, program, opportunity, development, excellent, property, great, growth, promotion, company, process, promote, career, white, engage | |

| 45 | move, many, opportunity, position, department, different, transfer, around, location, lot, difficult, hard, advance, available, entry | |

| 61 | experience, learn, lot, skill, different, gain, knowledge, difficult, great, interaction, training, exposure, variety, new, type | |

| 76 | expectation, management, support, training, high, well, set, goal, expect, due, little, need, pressure, issue, unrealistic | |

| Fair-compensation culture | 11 | great, benefit, salary, travel, competitive, culture, amazing, package, company, rule, strict, awesome, minimal, corporate, advancement |

| 18 | hotel, discount, employee, room, rate, benefit, travel, perk, cafeteria, meal, advance, renovate, loyalty, paid, reduce | |

| 20 | great, benefit, perk, awesome, location, atmosphere, sometimes, vary, strict, empower, diverse, staffed, throughout, starting, split | |

| 32 | hour, good, pay, flexible, work, schedule, scheduling, flexibility, overtime, management, little, enough, manager, boss, inconsistent | |

| 34 | company, great, benefit, reward, well, fantastic, amazing, offer, perk, excellent, recognize, vision, especially, recognition, hotels | |

| 42 | good, benefit, pay, union, fair, salary, plus, employee, appreciation, provide, non, teamwork, community, lower, quality | |

| 44 | good, work, salary, environment, professional, training, standard, experience, benefit, personal, facility, great, less, worldwide, learning | |

| 52 | great, benefit, lot, good, atmosphere, environment, fun, beautiful, culture, upward, mobility, move, movement, potential, consistent | |

| 67 | pay, job, good, people, easy, decent, enough, suck, get, nice, sometimes, low, slow, amount, work | |

| 96 | benefit, health, insurance, 401k, discount, medical, plan, vacation, offer, dental, pay, match, include, travel, etc | |

| Result-oriented culture | 80 | sale, bonus, sell, make, base, product, incentive, performance, high, review, potential, market, money, goal, leave |

| 87 | money, make, cut, business, tip, staff, spend, need, server, save, restaurant, enough, cost, keep, budget | |

| Overwork culture | 12 | hour, long, work, great, pay, flexible, foot, demand, simple, unpredictable, hair, emotional, transport, excessive, log |

| 17 | shift, night, hour, late, off, work, early, time, schedule, free, holiday, day, request, weekend, cover | |

| 21 | day, week, every, year, per, month, hour, two, off, get, work, even, three, few, raise | |

| 55 | holiday, day, off, hour, weekend, season, time, long, schedule, expect, week, every, open, busy, four | |

| 79 | pay, wage, low, minimum, hourly, hour, overtime, increase, less, tip, living, fair, barely, rate, uniform | |

| Job-insecurity culture | 31 | people, get, bad, just, know, ever, hire, leave, fire, right, keep, job, way, happen, look |

| 35 | job, work, difficult, security, keep, hard, responsibility, situation, able, deal, always, someone, help, find, come | |

| 71 | high, turnover, rate, pay, employee, low, management, extremely, stress, position, pressure, co-worker, amount, decent, christmas |

Note: (Lee & Choi, 2022).

To select independently coded topics, we adopted the decision rule suggested by Corritore et al. (2020) and selected topics for which at least two researchers independently matched the cultural attributes. The selection process performed by the three researchers resulted in 39 topics. As Table 1 shows, the conflicting attributes of organizational culture include multiple topics and key terms. Regarding resourceful attributes, collaborative culture has 12 topics, employee development has seven topics, and fair-compensation has 10 topics. For demanding attributes, results-orientation, overwork, and job insecurity encompassed two, five, and three topics, respectively. Finally, we added the quarterly probabilities of topics to measure the six cultural attributes at the firm level and analyzed the attractive configurations of organizational culture.

This study's outcome is the attractiveness of hotels as employers, and it adopted two indicators available in Glassdoor reviews as measurements (Fig. 1). First, Glassdoor allows users to rate “general employer satisfaction” on a five-point scale, which we adopted as an employer attractiveness outcome. Second, the response to the question, if the user “recommends the firm to friends” was also used as an outcome. We assigned 1 for a recommendation, 0 for neutral or no answer, and −1 for no recommendation. For a firm-level evaluation of employer attractiveness, we used the means of all quarterly ratings provided by the reviewers.

Analysis resultsCorrelation and multiple regression analysisTo test the propositions, we adopted a two-step approach, performing a traditional correlation and regression analysis before configurational analysis using fsQCA. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations. As predicted in the theoretical discussion, resourceful cultural attributes, such as collaboration, employee development, and fair-compensation culture, are positively and significantly correlated with employer attractiveness outcomes, such as employer satisfaction and recommendation. The result-oriented and job-insecurity cultures with demanding cultural attributes have a negative and significant correlation with employer attractiveness outcomes. However, contrary to theoretical prediction, overwork culture had no significant correlation with attractiveness outcomes, suggesting its complex relationship with other attributes in generating attractiveness outcomes.

Descriptive statistics and correlations (N = 2209).

| Means | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative | .117 | .029 | |||||||

| Employee development | .061 | .021 | −0.056⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Fair-compensation | .078 | .023 | .003 | .174⁎⁎ | |||||

| Result-oriented | .017 | .010 | −0.129⁎⁎ | −0.052* | −0.069⁎⁎ | ||||

| Overwork | .052 | .019 | −0.027 | −0.236⁎⁎ | −0.078⁎⁎ | −0.069⁎⁎ | |||

| Job-insecurity | .031 | .014 | −0.142⁎⁎ | −0.130⁎⁎ | −0.131⁎⁎ | .068⁎⁎ | −0.050* | ||

| Employer satisfaction | 3.371 | .584 | .276⁎⁎ | .242⁎⁎ | .234⁎⁎ | −0.192⁎⁎ | −0.032 | −0.165⁎⁎ | |

| Employer recommendation | .166 | .348 | .213⁎⁎ | .249⁎⁎ | .213⁎⁎ | −0.177⁎⁎ | −0.030 | −0.158⁎⁎ | .829⁎⁎ |

Note. * and ** denote significance at the 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively.

The regression model helps evaluate the influence of individual cultural attributes on employer attractiveness. As some cultural attributes can be more essential for determining the overall organizational culture and employer attractiveness outcomes, the regression model can help researchers assess the relative importance of individual attributes (Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). Furthermore, the preliminary regression analysis enables us to compare between the traditional variable-centered analysis and configurational approach, intensifying our understanding about the strengths in configurational analysis of organizational culture.

The regression analysis result in Table 3 demonstrates that all the resourceful attributes, such as collaborative (A: β = 0.263, p < .001; B: β = 0.200, p < .001), employee development (A: β = 0.217, p < .001; B: β = 0.224, p < .001), and fair-compensation (A: β = 0.180, p < .001; B: β = 0.158, p < .001), have positive and significant effect on both employer satisfaction and recommendation, respectively, thereby confirming the theoretical predictions. Additionally, the demanding attributes, such as result-oriented (A: β = −.128, p < .001; B: β = −.122, p < .001) and job-insecurity culture (A: β = −.066, p < .05; B: β = −.070, p < .05) have a negative and significant effect on employer satisfaction and recommendation, respectively. However, contrary to our theoretical prediction, an overwork culture has no negative impact on attractiveness outcomes.

Results of regression analysis (N = 2209).

| Model A Employer satisfaction | Model B Employer recommendation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path coefficient | T-statistic (P-value) | Path coefficient | T-statistic (P-value) | |

| Collaborative | .263*** | 13.478 (0.000) | .200*** | 10.042 (0.000) |

| Employee development | .217*** | 10.755 (0.000) | .224*** | 10.891 (0.000) |

| Fair-compensation | .180*** | 9.240 (0.000) | .158*** | 7.924 (0.000) |

| Result-oriented | −0.128*** | −6.598 (0.000) | −0.122*** | −6.133 (0.000) |

| Overwork | .029 | 1.446 (0.148) | .029 | 1.438 (0.150) |

| Job-insecurity | −0.066* | −3.347 (0.001) | −0.070* | −3.480 (0.001) |

| F-value | 92.621*** | 71.979*** | ||

| R2 | .199 | .162 | ||

Note. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 5 %, 1 % and 0.1 % levels, respectively.

For a configurational analysis of hotels’ organizational culture, we adopted fsQCA using the fsQCA 3.0 software. The fsQCA approach examines the relationship between all possible combinations of predictors and the outcome of interest, generating various combinations of conditions that lead to the absence of outcomes, positive outcomes, or negative outcomes (Fiss, 2007; Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ragin, 2009). Given our research goal of understanding the cultural configuration that generates employer attractiveness, we focused on identifying configurations leading to the presence of outcomes, specifically employer satisfaction and recommendation.

First, we initially performed calibration, which was aimed at allocating the set memberships of each case under causal conditions, such as six cultural attributes and two employer attractiveness variables. In fsQCA, the calibration process assigns collective membership to cases using either direct or indirect methods. In direct calibration, researchers set exactly three qualitative breakpoints indicating full-set membership, full-set non-membership, and intermediate-set membership in the fuzzy set for each case. By contrast, in indirect calibration, the measurement is rescaled based on qualitative evaluations, and researchers may choose to calibrate a measure differently based on their investigation (Fiss, 2007; Ragin, 2009). The selection of either method depends on researchers’ substantive knowledge of the data and the underlying theory (Fiss, 2007; Ragin, 2009). Considering that the procedure is clear for verification and replication by others, researchers have discretion in determining the procedure for assigning fuzzy values to cases and adopting threshold values.

Because the data in this study do not completely follow a normal distribution and exhibit skewness, we set the full membership points of the six antecedents and two outcome variables as the upper quartile (75 %) of the case data, the intersection points as the median (50 %) of the case data, and the complete non-membership points as the lower quartile (10 %). Table 4 lists the anchor point calibrations. Moreover, in the fsQCA, cases with an intermediate set membership of exactly 0.5 are typically dropped. To address this issue, it is recommended to add a constant of 0.001 to the causal and outcome conditions below a full membership score of 1 (Fiss, 2007; Ragin, 2009). Thus, we added 0.001 to all predictor and outcome conditions after calibration was conducted.

Calibration percentile and statistics.

| Percentile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| .75 | .5 | .1 | |

| Employer satisfaction | 3.7857 | 3.4286 | 2.5714 |

| Employer recommendation | .4 | .2001 | - 0.3333 |

| Collaborative | .1338 | .1151 | .1338 |

| Employee development | .0739 | .06 | .0739 |

| Fair-compensation | .0922 | .0776 | .0922 |

| Result-oriented | .0224 | .0153 | .0224 |

| Overwork | .0638 | .0502 | .0638 |

| Job-insecurity | .0395 | .0303 | .0395 |

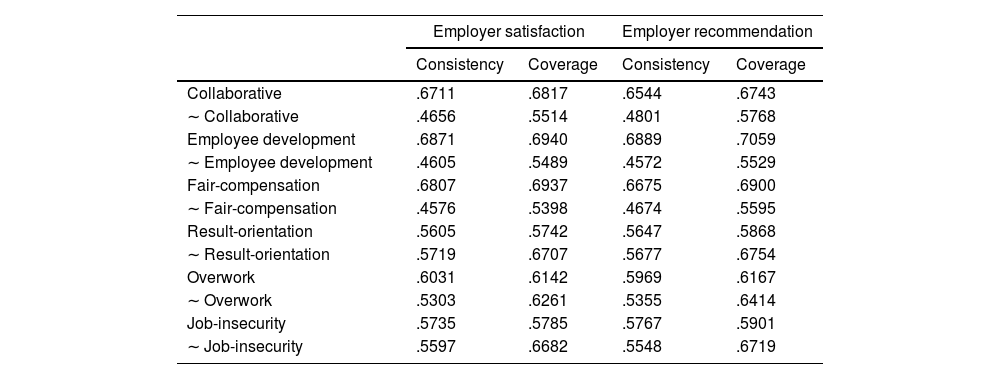

Second, based on the calibration, we performed both necessity and sufficiency analysis. On the one hand, before building a truth table, we examined whether any of the causal conditions could be considered necessary. The fsQCA tool enables researchers to detect necessary conditions that help facilitate the occurrence of an event. The consistency threshold of the necessity analysis is set at 0.9. Table 5 displays the results of the necessity analysis. No necessary consistency of the antecedent cultural conditions on employer satisfaction and recommendation is above 0.9, indicating that no single cultural attribute is necessary for attractiveness outcomes. In other words, a single cultural attribute has insufficient explanatory power for employer attractiveness. Therefore, this result led us to further analyze the combined effect of antecedent conditions.

Necessity analysis.

| Employer satisfaction | Employer recommendation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| Collaborative | .6711 | .6817 | .6544 | .6743 |

| ∼ Collaborative | .4656 | .5514 | .4801 | .5768 |

| Employee development | .6871 | .6940 | .6889 | .7059 |

| ∼ Employee development | .4605 | .5489 | .4572 | .5529 |

| Fair-compensation | .6807 | .6937 | .6675 | .6900 |

| ∼ Fair-compensation | .4576 | .5398 | .4674 | .5595 |

| Result-orientation | .5605 | .5742 | .5647 | .5868 |

| ∼ Result-orientation | .5719 | .6707 | .5677 | .6754 |

| Overwork | .6031 | .6142 | .5969 | .6167 |

| ∼ Overwork | .5303 | .6261 | .5355 | .6414 |

| Job-insecurity | .5735 | .5785 | .5767 | .5901 |

| ∼ Job-insecurity | .5597 | .6682 | .5548 | .6719 |

On the other hand, after confirming that no single cultural attribute constitutes a necessary condition for employer attractiveness, we analyzed the conditional combination of the six cultural dimensions to obtain employer attractiveness. To determine the appropriate causal combinations generating the outcome, the number of rows in the truth table should be reduced. We adopted two reduction criteria. First, considering the large sample size of our study, the minimum number of cases to consider a combination relevant was set at 12. Second, consistency criteria indicated the extent to which a combination of causal conditions is consistent in relation to the outcome. As the consistency threshold should not be less than 0.75 (Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ragin, 2009), we set the consistency threshold at 0.89. After eliminating the combinations that do not meet the above two conditions from the truth table, Figs. 2 and 3 present the results of fsQCA for employer satisfaction and recommendation, respectively.

The output of the truth table typically presents three types of solutions: complex, intermediate, and parsimonious. To generate a valid truth table, researchers typically focus on both intermediate and parsimonious solutions and identify both core and peripheral conditions (Fiss, 2007; Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ragin, 2009). A complex solution generates all possible combinations of attributes, making interpreting the solutions difficult. The parsimonious solution only presents the core conditions, which are essential conditions that cannot be excluded from any solution. The intermediate solution presents both the core and peripheral conditions by performing a counterfactual analysis of the complex and parsimonious solutions. Many researchers have presented final solutions by comparing and elaborating on parsimonious and intermediate solutions (Pappas & Woodside, 2021).

However, in our analysis, all three solutions (complex, intermediate, and parsimonious) yielded identical solutions without distinguishing between the core and peripheral conditions. These identical solutions may result from the large dataset used in this study (Reichert et al., 2016). Previous fsQCA studies using large sample sizes have demonstrated this tendency. For example, Yang's (2018) research with a sample of 2163 adults, Tho and Trang's (2015) work with a sample of 843 students, and Reichert et al.’s (2016) analysis of 614 low-tech firms yielded identical solutions for all three types. Thus, we interpreted the solution results directly, without elaborating on possible scenarios, by comparing the core and peripheral conditions.

Each column in Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrates a combination of conditions or configuration of cultural attributes associated with employer attractiveness, such as employer satisfaction and recommendation. The black circle in the figure indicates the presence of a condition that leads to an outcome of interest; the crossed-out circle denotes the absence of a condition that causes an outcome; and the blank spaces represent a “don't care” situation, suggesting that neither the presence nor absence of the condition is related to the outcome. At the bottom, the figures show the consistency, unique coverage, and raw coverage for each configuration as well as the solution consistencies and solution coverage for the configurations as a whole.

Each column in Figs. 2 and 3 presents the configuration of cultural attributes that are sufficient to predict high employer satisfaction and recommendation, with consistency and coverage measures for individual configurations as well as the whole solution. Regarding employer satisfaction in Fig. 2, the fsQCA generated six configurations with an overall solution consistency of 0.8327 and an overall solution coverage of 0.5129. For the employer recommendation in Fig. 3, the fuzzy-set analysis presents seven configurations of cultural attributes with an overall solution consistency of 0.8079 and an overall solution coverage of 0.5509. Regarding the overall solution consistency, researchers typically suggest a minimum level of 0.75 and recommend a value of 0.80 (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Given these criteria, all our results are at the recommended levels of solution consistency. Furthermore, they present a similar group of configurations, largely supporting the three configurational propositions.

Third, the truth table of the sufficiency analysis confirms the three configurational propositions. Proposition 1 suggests that the attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture consists of different sets of cultural attributes. Supporting this prediction, the analysis results determine that three different groups of the 13 cultural configurations in Figs. 2 and 3 achieve hotel employer attractiveness. The first group consists of fully resourced configurations (A1 and B1), in which the combination of all three resourceful attributes (collaborative, employee development, and fair-compensation cultures) leads to employer satisfaction and recommendation, regardless of the presence or absence of demanding attributes.

The second group includes resourced and low-demanding configurations (A2, A3, B2, B3, and B4), which combine the presence of two resourceful attributes and the absence of detrimental demanding attributes. This group highlights the fact that an organizational culture with two resource attributes can predict employer attractiveness when two detrimental attributes (e.g., result-orientated and job-insecurity culture) are absent.

The third group encompasses fairly compensated overwork configurations (A4, A5, A6, B5, B6, and B7), which identify a strong and novel interaction effect between resourceful and demanding attributes in predicting employer attractiveness. This unique group strongly suggests that employees willingly accept or even welcome an overworked culture in which hotel employers compensate them fairly. Although this group involves some complexities regarding the presence and absence of other cultural attributes, it highlights a strong synergistic effect arising from combining fair-compensation and an overtime culture in generating employer satisfaction and recommendation in hotel firms.

Proposition 2 predicts that an attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture includes more resourceful than demanding attributes. Supporting this prediction, the first group of fully resourced configurations (A1 and B1) attests that the dominance of resourceful cultural attributes constitutes a crucial condition for employer attractiveness. Furthermore, the second group of resourced and low-demanding configurations (A2, A3, B2, B3, and B4) and two fairly compensated overwork configurations (A4, A5, and B5) show that the presence of two resourceful attributes achieves attractiveness in the absence of detrimental demanding attributes.

Proposition 3, based on the competing value framework of the configurational approach, predicts that an attractive configuration of hotels’ organizational culture achieves congruence between resourceful and demanding attributes. The third group of fairly compensated overwork configurations (A4, A5, A6, B5, B6, and B7) suggests that the pressure and work overload culture in hotels can have synergistic interactions with the fair-compensation culture to generate employer satisfaction and recommendation. This group indicates that employees in an overtime culture may feel satisfied with and even recommend hotel firms when they receive fair-compensation for their work overload and longer working hours. This result reveals novel insights into the limitations of regression analysis. Contrary to its insignificant effects in the regression models presented in Table 3, the fsQCA highlights the previously unknown complex interaction effects of overwork culture, demonstrating its crucial synergistic impact in determining employer attractiveness.

Comparative discussions of analysis resultsWith the goal of advancing the holistic understanding of organizational culture, we adopted a novel research methodology of review-based topic modeling and configurational analysis, which overcame the limitations of survey-based measurement and regression analysis in the existing literature. Comparison of the findings of different data analysis methodologies can reveal various insights hidden within the same dataset. The analysis results in the previous section not only enable us to make systematic comparisons between different methodologies but also highlight the benefits of fsQCA in intensifying our understanding of the holistic and competing characteristics of organizational culture.

The regression analysis determined that all resourceful attributes of organizational culture have a positive effect on attractiveness outcomes, although collaborative and employee development cultures have a stronger influence than fair-compensation cultures in general (Table 3). In contrast, the fsQCA revealed that employee development culture is present in 10 out of 13 configurations, fair-compensation culture appears in 9, and collaborative culture is involved in 9 to explain employer attractiveness (Figs. 2 and 3). This fuzzy-set result can clarify the comparative contribution of resourceful attributes to employer attractiveness, providing different assessments from the regression analysis. Regarding the impact of a demanding culture, the regression analysis indicated that both result-oriented and job-insecurity cultures have a negative effect on employer attractiveness (Table 3). Similarly, the fsQCA reveals that the absence of result-oriented culture in 5 out of 13 configurations leads to employer attractiveness, and the absence of job-insecurity culture in 4 configurations contributes to attractiveness outcomes (Figs. 2 and 3).

The most significant aspect of the comparative analysis was the role of overwork culture, particularly its synergistic interactions with fair-compensation culture, in explaining hotels’ employer attractiveness. The holistic nature of organizational culture presumes nonlinearity of causation, proposing that cultural dimensions that are causally associated in a configuration are inversely related in different configurations (Fiss, 2007; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). Although overwork culture was found to be insignificant in the regression analysis (Table 3), the fsQCA shows that the presence of overwork culture results in employer attractiveness in 6 out of 13 configurations in combination with fair-compensation culture (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast to regression analysis, overwork culture in the fuzzy-set approach supports the competing value framework (Chen et al., 2023; Marinova et al., 2019; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983) by revealing that contrasting cultural attributes work together to generate meaningful outcomes.

Discussion and conclusionsDeveloping a competitive advantage in the labor market is one of the most crucial factors for organizations to gain competitiveness and business success. Particularly, hotels should improve their employer attractiveness to acquire talented and motivated employees. Under fierce labor market competition, hotels can differentiate themselves by promoting employer attractiveness. This study conceptualized conflicting cultural attributes and makes configurational propositions to investigate the influence of organizational culture on employer attractiveness. For empirical analysis, we collected industry-wide data on employee reviews in the US, adopted topic modeling to measure cultural attributes, and performed fsQCA to test the configurational propositions. Exploring an unearthed theoretical relationship in organizational culture and combining novel methodologies for a holistic analysis, this study presents the following theoretical, methodological, and practical implications.

Theoretical implicationsA distinctive theoretical aspect of this research is to deepen our understanding of the less-studied theoretical relationship between organizational culture and employer attractiveness based on a study of the hotel industry in the US. Despite the long academic history of organizational culture studies, the majority of existing literature focuses on analyzing its effect on internal organizational members to explain the impact of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness and performance. However, this study recognized organizational culture's appeal to the external labor market and prospective employees, and proposed that a resourceful organizational culture could attract talented employees, encourage applicants to accept a job, and positively influence their tenure once hired (Catanzaro et al., 2010; Lee & Choi, 2022; Sommer et al., 2017). The analysis results confirmed that different cultures can play a critical role in developing and maintaining an organization's attractiveness as an employer.

Another theoretical distinctiveness of this study lies in its configurational analysis of holistic organizational culture. Confirming the core premises of configurational analysis, this study demonstrated the equifinality, synergistic interactions, and nonlinearity of organizational culture in determining employer attractiveness. Our configurational analysis attested to equifinality by identifying three groups of 13 configurations with distinct sets of cultural attributes, including fully resourced configurations, resourced and low-demanding configurations, and fairly compensated overwork configurations of organizational culture, all of which contribute to hotels’ employer attractiveness. Supporting the synergetic interactions and nonlinearity of the causation of holistic organizational culture, we observed that in resourced and low-demanding configurations, the absence of detrimental cultural attributes can significantly impact the outcomes. Specifically, the absence of a result-oriented and job-insecurity cultures was found to interact with two resourceful attributes in generating employer attractiveness, highlighting the nonlinearity of causation in the configurational analysis.

Finally, and more significantly, the fairly compensated overwork configurations observed in this study highlight the value of configuration analysis over regression analysis. The regression model found no influence of an overwork culture, disregarding its hidden role in employer attractiveness. However, configuration analysis revealed that an overwork culture could have a positive synergistic impact on employer attractiveness in combination with a fair-compensation culture. These results demonstrate that a configuration analysis offers alternative and superior insights over regression models by identifying crucial combinations of conflicting cultural attributes in determining critical outcomes.

Methodological implicationsOne of the most significant contributions of this study is its innovative combination of research methodologies to advance organizational culture studies. The existing literature has predominantly relied on survey-based measurements and regression analyses, but methodological constraints have hindered researchers from fully realizing the holistic and systematic underpinnings of the theory (Marinova et al., 2019; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014). To overcome these limitations, we adopted review-based topic modeling and fsQCA for configurational analysis.

Most existing literature utilizes self-report surveys with small sample populations, primarily focusing on managers and employees. Consequently, these often suffer from the concern of overly reflecting a few individuals’ personal perceptions in assessing cultural attributes, while embracing serious issues of social desirability bias (Lee & Choi, 2023). In contrast, employee reviews in our study offer numerous advantages over traditional self-report surveys, as these provide large-scale data scalability, low social desirability bias, and reduced response bias. This platform enables users to provide free-form textual data in real-life language, allowing employees to express various aspects of organizational life and internally shared beliefs without being constrained by the theoretical constructs adopted in the survey questionnaires (Lee & Choi, 2023).

Based on an industry-wide dataset of Glassdoor reviews, we conducted an LDA to measure cultural attributes. Although the large-scale employee review data enhance the generality of the analysis results, the topic modeling of LDA provides deeper insights into the cultural elements expressed in employees’ daily language. The topics extracted by LDA can capture the linguistic signatures of cultural attributes, effectively revealing internally shared organizational values, norms, and beliefs. Thus, the topic modeling approach can better present different cultural attributes with high face validity (Corritore et al., 2020; Lee & Choi, 2023).

For configurational analysis, we adopted fsQCA, which offers numerous benefits over clustering analysis. fsQCA helps researchers identify logically simplified explanations that describe how different combinations of cultural attributes lead to employer attractiveness (Fiss, 2007; Ostroff & Schulte, 2014; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). By generating configurations that constitute sufficient and/or necessary conditions for attractiveness, the fsQCA enables researchers to understand causal complexity using fine-grained data. Particularly, it not only allows for the identification of specific cases in the sample to verify novel propositions but also presents alternative explanations leading to the same employer attractiveness. Combining fsQCA with other data analysis techniques, such as regression analysis, can reveal hidden stories within the same dataset, resulting in novel findings.

Practical implicationsOur study findings provide hotel leaders and human resource management with critical insights for developing organizational culture and promoting organizational reputation in the labor market (Klein et al., 2013). In general, although hotels can achieve employer attractiveness by developing resourceful cultural attributes as well as by preventing demanding attributes, our study suggests that there are several paths and sets of cultural attributes to gain high employer attractiveness. It highlights not only the significance of understanding individual cultural attributes but also their complex interactions and combinations to generate attractiveness. Specifically, preventing detrimentally demanding attributes, such as result-oriented and job-insecurity cultures, is as significant as investing in constructing resourceful cultural attributes.

Furthermore, this study suggests that achieving fine congruence between opposing attributes of organizational culture can heighten employer attractiveness. We showed that an overwork culture induces employees’ recommendations under the condition that hotels fairly compensate for employees’ labor contributions. An overwork culture develops when hotels demand excessive work hours from their employees to cope with work overload without hiring new employees (Mazzetti et al., 2016). However, many hotel employees may embrace an overwork culture when organizational rules and norms fairly reward their extra efforts. Thus, to achieve higher competitiveness in the labor market, management should have an accurate understanding of the synergetic interactions in cultural configurations that maintain close congruence between conflicting attributes.

Limitations and future researchOur study presents novel theoretical directions, comprehensive industry-wide datasets, and new combinations of research methodologies that offer numerous insights. However, this study has some limitations that future research should address. First, this study relied on employee reviews on the Glassdoor platform and the possibility of fake reviews causing contamination concerns. Platform users have incentives to undertake fake reviews, and biased reviews may undermine the credibility of the review data (Luca & Zervas, 2016). Regarding the cheating problem, however, it is suggested that the Glassdoor's “give to get” policy as well as “cons-and-pros” policy could discourage polarized reviews (Sull, Turconi, & Sull, 2020). Second, this study highlighted the synergistic role of an overwork culture in ensuring employer attractiveness. The hazards of extreme overwork cultures should not be ignored (Mazzetti et al., 2016). This study is not specific to how strongly an overwork culture is still tolerable to synergetic interactions with fair-compensation culture to gain employer attractiveness. Third, this study collected industry-wide employee reviews of hotels’ organizational culture to overcome the limitations associated with traditional self-reporting survey instruments. However, researchers can further advance the literature on organizational culture by exploring additional data sources and research instruments (Jung et al., 2009), such as corporate document analysis, annual reports, social media posts, human resource management reports, and perspectives from external stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, buyers, and partners). Fourth, the study's empirical analysis focused on English-speaking users in the US; thus, future research may enhance the theoretical validity by conducting empirical analysis in different national contexts and languages. Despite these limitations, our study provides new theoretical, methodological, and practical insights highlighting the importance of configurational analysis for a holistic understanding of organizational culture.

CRediT authorship contribution statementKyoung-Joo Lee: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Sun-Yong Choi: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation.

The work of S.-Y. Choi was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1F1A1046138) and the Gachon University Research Fund of 2024 (GCU- 202404060001).