This study focuses on the structure of self-learning as a multidimensional construct, through competences such as autonomy and study planning of undergraduate students, over the last three years. The objective of this study, framed by Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), aims to gain insights into the acceptance of self-learning in online educational models within a post-pandemic, university context. More specifically and innovatively, this study sets out to explore gender differences in self-learning adoption, as previous studies have observed various findings.

Action variables and motivation play crucial roles in self-learning. Davis's original TAM model (1989) put forward five key variables, all of which are dealt with both theoretically and practically in this study. Additionally, this study puts forward several hypotheses based on the TAM model, addressing perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, attitude, user satisfaction and intention to use in the context of online learning.

From a practical perspective, a multi-group analysis is carried out that has been applied to a sample made up of 313 male and female Spanish university students from different areas of knowledge. Questionnaires were conducted with all participants and statistics calculated; the results make it possible to affirm that the different dimensions of the self-learning structure are interrelated, and significant differences between men and women are observed in the adoption of the model.

The study concludes that online education fosters a positive attitude toward self-learning in female students, unlike what happens with male students. While the sample size might be considered a limitation of the study, the study nonetheless observes that female students appear to be more inclined to develop a sense of self-learning. In contrast, male students—though consumers of self-learning– do not generate the same attitude. Therefore, the conclusion can be drawn that online teaching is a way to promote self-learning in women, which may inform universities when designing programs promoting student autonomy with new technologies.

The first years of the 21st century have been marked by innovative educational models that distanced themselves from traditional teaching and were oriented towards a new education based on student participation, through methodologies such as student-centred learning (Weimer, 2002) and the flipped classroom (Bergmann & Sams, 2012). With this principle, the aim was for students to learn not only from the teacher, but also from their peers, and for all of them to learn collaboratively and, consequently, reach a kind of shared common knowledge.

These changes in education were necessary, since globalised learning required placing the student in front of a contextualised world that provided the means for their participation in the classroom. Over the years, the student has been observed to progress in terms of protagonism and participation, however, there is a non-existent attitude towards self-learning. Cheng (2005) states that the capacity for self-learning is a concern of current educational reforms, and Villanueva (2000) points out that this attitude of self-learning should be a constant in a student's life.

Autonomous learning refers to the degree to which a student participates in the learning process with regard to the implication of timing, resources and objectives (Mendoza, 2017). It has been presented as an objective for politicians and academics for more than a decade since it responds to students’ need to acquire new skills demanded by the labour market, such as developing their ability to debate and present ideas, involving students in challenges that require them to carry out additional research beyond the material provided in the classroom, and having students make decisions about their learning according to their interests (Moreno & Martínez, 2007).

Based on this, there is a need to develop a positive attitude towards learning, and this is achieved through the problem-based learning method (PBL) (Morales-Bueno & Landa-Fitzgerald, 2004; Reyes-Argüelles et al., 2022).

PBL, according to Poot-Delgado (2013), consists of stimulating “certain cognitive abilities that are stimulated to a lesser degree by traditional methods, allowing the promotion of learning, such as critical thinking, creativity, decision-making in new situations and communication skills”.

Precisely, this model makes more sense than ever when the current education sector should be making a conscious effort to promote active student learning (Reyes-Argüelles et al., 2022), while understanding learning as the achievement of a set of goals (Moreno & Martínez, 2007), which, in this case, are achieved through a technological component.

Technology and self-learning have always had a close relationship (Rashid & Asghar, 2016; Bizami et al., 2023) due to the support the former provides for student learning. In principle, self-learning is promoted by e-learning, which in turn lends itself to blended learning (b-learning), where the online element is combined with the face-to-face format. Young people experience the ubiquity of their learning through mobile learning (m-learning), which has given rise to the latest trends in transformational learning.

Based on this evolution and the continuous need for learning, the objective of this study focuses on gaining insights into the level of acceptance of self-learning in educational models within the post-pandemic context and more specifically, what differences there might be when considering men and women—in other words, gender– as the external variable. The study is approached from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which is based on the user's acceptance of the technology at hand. Additionally, as it is of particular interest to determine if there are differences demonstrated between men and women regarding their use of self-learning, an extensive comparison of results is offered.

Recent studies explore the outcomes of self-learning through flipped classroom programs (Huang, 2020), the use of audiovisual educational microcontent to foster self-learning motivation (Pastor-Rodríguez et al., 2022), and the issues associated with the high dropout rate in massive open online courses (MOOCs) (Molina & Cancell, 2022). Having said that, the existing literature on student self-learning in the context of online education and its evaluation through the TAM model is limited. Studies based on this model predominantly focus on the relationship between self-efficacy and e-learning, highlighting the positive impact of perceived usefulness and ease of use (Peng et al., 2023).

This article intends to contribute to the study of the TAM model with respect to self-learning and to determine if there are gender differences present. The authors consider this to be a topic of interest that has grown since the pandemic, as represented by several articles from recent years (Garrido-Gutiérrez et al., 2023; Estriegana et al., 2023; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2022). While it is acknowledged that this topic has been studied in other countries (Peng & Hwang, 2021; Fauzi et al., 2021; Sukendro et al., 2020), in the Spanish context, the production of literature is much lower, leaving the representation of Spanish students in the matter of self-learning behind. Nevertheless, the existing works from Spain on this subject rank second in terms of citations by country of origin, according to Estriegana et al. (2023).

The results of this research can help universities to design programs based on the autonomy of students in relation to the use they make of new technologies. Technology by itself does not work, and good software design is insufficient if no strategy is employed at design time. Technology, however, does have the potential to make students more satisfied and therefore more receptive, which has a direct impact on learning and longer study hours.

The above-mentioned objectives will be dealt with as follows: after an Introduction to the topic of study, an approach to concepts and expected outcomes of the study can be found in Section 2. In Section 3, the sample and methodology used to carry out the investigation are put forward in depth. After the presentation of the model, the results obtained are presented in Section 4. Finally, the Discussion is addressed in Section 5 along with the conclusions and future lines of research.

Theoretical framework and hypothesisTAM model and self-learningSelf-learning and information technologies have been studied from different perspectives, the most relevant of which are highlighted for this study, from the fields of motivational psychology (Schunk, 1996) to the self-learning environment or space (Cheng, 1994). However, the self-learning model proposed by Mok and Cheng (2001), which advocates for the use of networked ICTs to transform the learner into a motivated self-learner with the support of technology, deserves more attention. In this way, the present authors aim to promote independent lifelong self-learning as a sine qua non.

It should be noted that self-learning is based on action variables (Yuen & Cheng, 1997; Argyris & Schön, 1974) and the existence of motivation to increase knowledge (Mok & Cheng, 2000). In this sense, Rheinberg et al. (2000) point out that in order for the learner to be motivated to self-learn, they must perceive that they will achieve a positive result, as well as having personal motivation inspired by their family and social environment. Also relevant is the study of online self-learning by people over 55 using the TAM model, which highlights that men's self-learning is influenced by "perceived usefulness and social influence", while women's self-learning is more influenced by "perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and social influence" (Liu & Zhang, 2023).

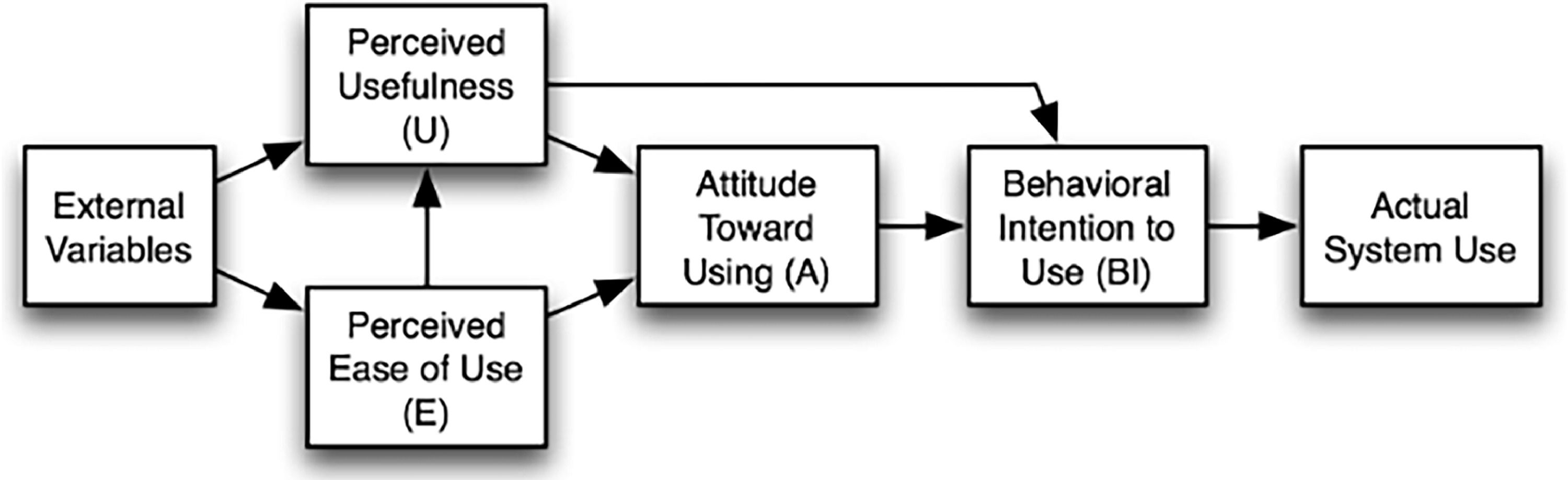

At the end of the 20th century, Davis (1989) presented the TAM model. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the model analyses the use of technology through five variables: perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, attitude towards use, intention to use and actual use. Other researchers, such as Sheldon (2016) and Scherer et al. (2019), have recently examined the importance of various models applicable to the study of technology, such as UTAUT and TAM. These works highlight TAM as the most suitable model for analysing the relationship between intention to use and actual use of technology. However, Scherer et al. (2019) point out in their analysis of technology used by teachers that the TAM model does not provide conclusions about what type of content the teacher should deliver to integrate technology in the classroom. Additionally, Sheldon (2016) emphasizes the significant role of social influence within the model. It is worth noting that the extrinsic factor of the influence of family, friends and teachers has been proposed as very important for the performance of a certain behaviour (Agudo-Peregrina et al., 2014).

TAM model and genderContinuing with the analysis of gender and technology using the TAM model, there is disagreement in the scientific literature regarding the influence of technology acceptance and use. Padilla-Meléndez et al. (2013) point to different factors, with women demonstrating attitudes towards using technology that can best be described as playfulness and entertainment, whereas men display attitudes that are better influenced by perceived usefulness. Similarly, González-Gómez et al. (2012) point to a female preference for participation. Other authors find no significant differences (Terzis & Economides, 2011; Hung et al., 2010).

Of note is a post-pandemic research study based on the TAM method, which analysed the acceptance of the use of Zoom as a language learning tool (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021). The results suggest a relationship between learner experience and perceived usefulness, a finding also noted by Hsu and Lu (2004).

Similarly, Zhang and Prybutok (2003) analyse e-commerce and find that perceived usefulness is more important for men, while perceived ease of use is much more important for women. The authors conclude that "gender is a moderately significant variable" (2003).

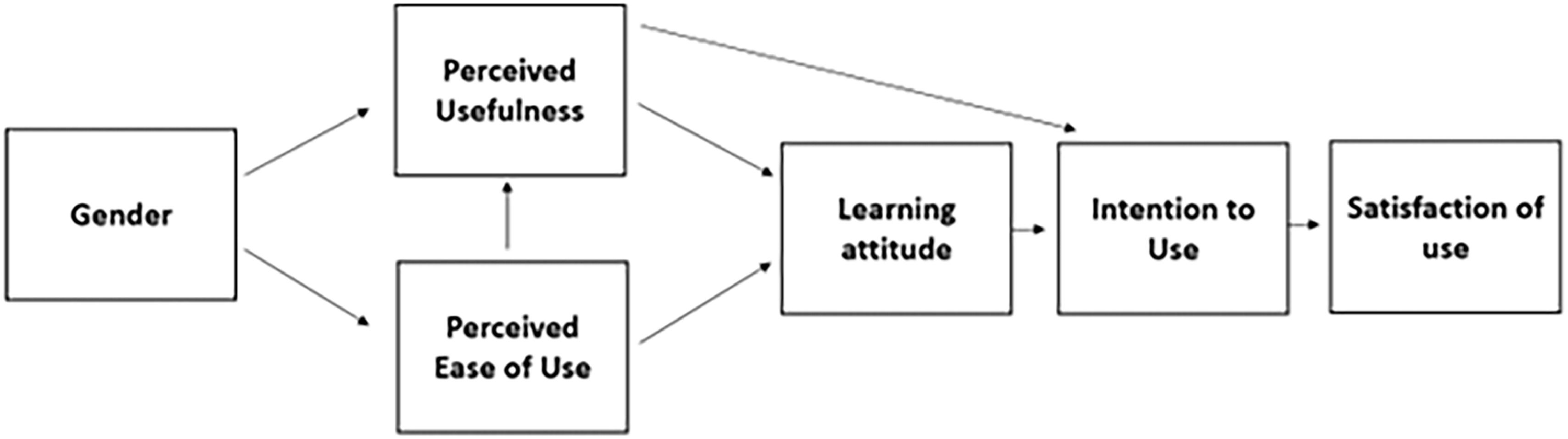

In the TAM model, the external variables determine the influences within the model. Gender is considered an external variable that determines the influence and relationships of the other factors. Fig. 2 shows gender as an external variable in the TAM model.

HypothesesBased on the TAM model, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

Perceived ease of usePerceived ease of use refers to the degree to which an individual believes that the adoption of ICT (Information and Communications Technology) is effortless and that his or her performance will be enhanced by using this learning method (Davis, 1989). In the context of online learning, Davis defines perceived ease of use as the student's sense of security and belief that the technological tool will provide freedom and peace of mind. Years later, Šumak et al. (2011) conducted a literature review of models studying e-learning and concluded that the TAM model is the most widely used in the field, in addition to finding that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness have a direct impact on adoption.

Cheng (2011) points out that the perceived ease of online learning has a direct impact on students' feelings about the usefulness of online learning and is important enough to be included in the seven factors that play a role in why a student decides to study online, as reported by Nguyen et al. (2020): "Computer self-efficacy, computer experience, enjoyment, system characteristics and subjective norm, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness".

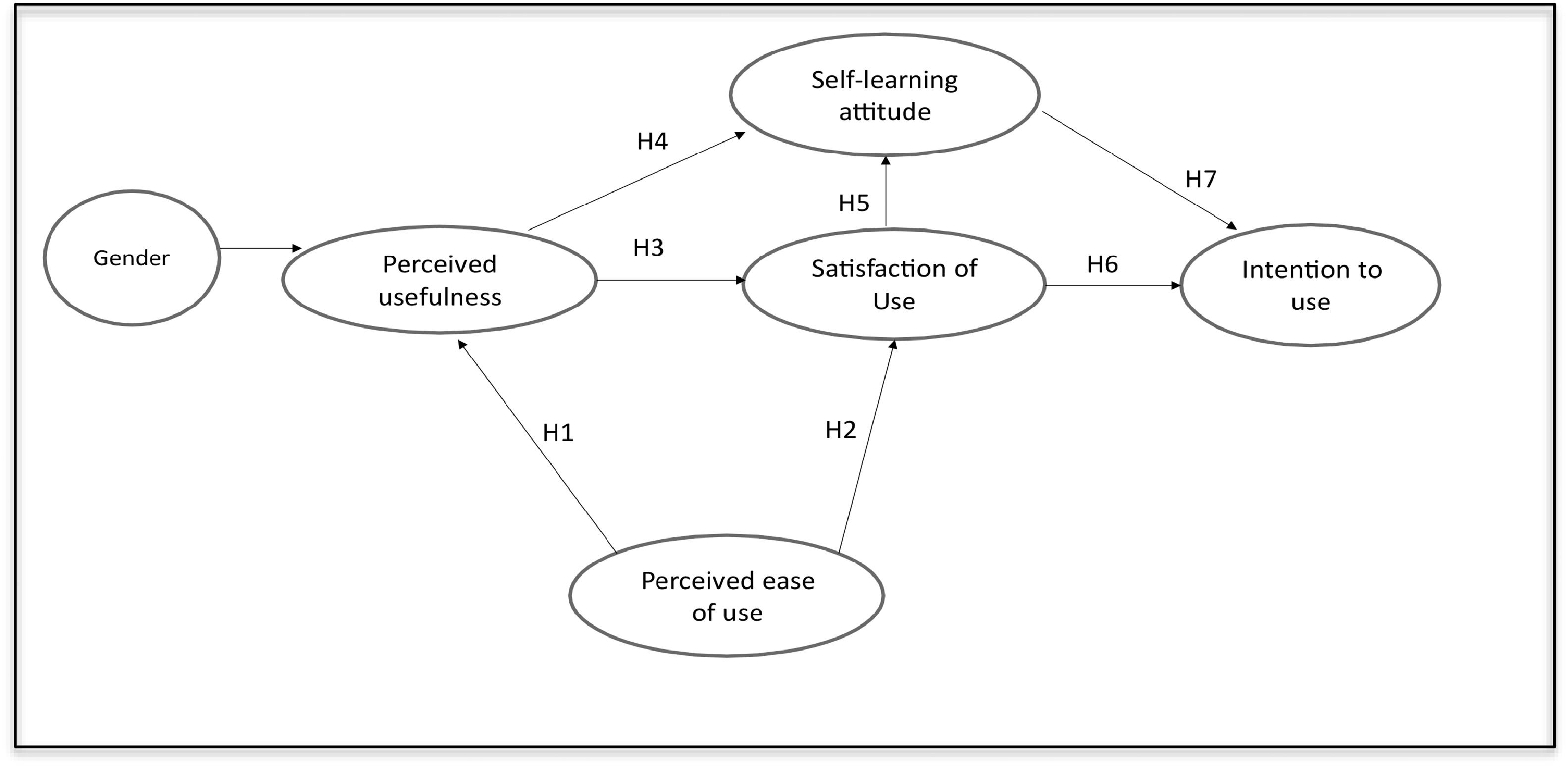

These are our hypotheses (Fig. 3):

Hypothesis 1

(H1). The perceived ease of use of the learning system provides students—while differences between male and females exist– with a perception of usefulness that encourages them—to differing degrees depending on their gender– to continue learning with digital tools.

Hypothesis 2

(H2). The perceived ease of use of the learning system has a positive effect on students' satisfaction—to differing degrees depending on their gender– with the learning process.

Perceived usefulnessPerceived usefulness is an individual's belief that the use of a tool can improve his or her productivity (Marangunić & Granić, 2015). Recent research in e-learning suggests that perceived usefulness and ease of use promote motivation to use technology (Ansong-Gyimah, 2020; Mailizar et al., 2021). However, Park (2009) disagrees with the relationship between perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and the intention or willingness to use e-learning and points to self-efficacy as the most salient e-learning construct.

In line with this, Khan et al. (2023) find that self-efficacy increases the perceived sense of usefulness towards online learning, defining self-efficacy as an external variable that determines the skills and competences to perform a particular task. Similarly, Alsabawy et al. (2016) establish the quality of the system (interface, usability, etc.) as a determinant variable of online courses that positively affects perceived usefulness.

To confirm the perceived usefulness of online learning, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 3

(H3). The perceived usefulness of online learning increases student satisfaction– to differing degrees depending on their gender– to continue to learn using the available tools.

AttitudeAttitude is the user's behaviour and intention to proceed with the technology. Many studies point to the positive effect of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness on attitude (Davis, 1989; Zhu & Lin, 2008). However, there is some uncertainty in defining the exact role of this behaviour in the TAM model, as some empirical studies consider the relationship between attitude and final adoption of IT to be incomplete (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000).

Kim et al. (2009) distinguish between "the effect of attitude strength", which can be either low or high, and note that these conditions can change the basis of motivation towards acceptance of using technology, considering that if a user has a weak intention towards using technology, which has a direct impact on the feeling of acceptance towards its use, and conversely, if the attitude towards the tool is positive, the corresponding behaviour displays less resistance. Karahanna et al. (1999) also distinguish between pre- and post-approval attitudes to usefulness, pointing out that the former is based on both perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, while the latter is based only on perceived usefulness.

Another aspect to highlight in relation to this construct is found in online learning. In this context, Lin et al. (2014) define interactivity as the main external variable of the TAM model in determining attitudes. It should be noted that the reality of online learning is based on the possession of the necessary tools to find information immediately and, as a consequence, offers the possibility of self-learning. Meng and Luo (2017) find that all variables in the TAM model have a positive effect on self-learning, distinguishing that perceived usefulness has a direct relationship with attitude.

The proposed hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 4

(H4). The perception of usefulness developed by potential learners increases positive attitudes towards self-learning.

User satisfactionSatisfaction of use is linked to the extent to which the user recognizes that the technology fulfils their expectations. Several studies highlight that ease of use can guide the user towards actual use, and that the more familiar the user is with the tool, the more determined they may be to use it (Baroudi et al., 1986). Other research, however, disagrees with the idea that the relationship between satisfaction and use is exclusively causal and points to a much more relevant relationship between attitude and IT use (Al-Gahtani & King, 1999; Melone, 1990).

Similarly, Choi (2005) defines educational satisfaction as the positive outcome between student expectations and their overall evaluation of the experience. In addition, Wei and Chou (2020) estimate that this satisfaction is the learner's intimate response to their online learning and, consequently, this satisfaction is linked to how the online learning is evaluated. Satisfaction is indeed a perception, a feeling of satisfaction with the positive completion of an activity, which might only be diminished by predetermined expectations. Meng and Luo (2017) find that university students' online self-learning is directly related to satisfaction and note that this perception of self-learning has a positive impression on “continued intention”.

Based on previous research, the following hypotheses are developed:

Hypothesis 5

(H5). Students' satisfaction with online learning will increase their positive attitude towards self-learning.

Hypothesis 6

(H6). Satisfaction with online learning will increase the intention to use the tools available to students for educational training.

Intention to useIntention to use is the individual's determination to choose a particular behaviour. Specifically, the TAM model is based on the analysis of perceived usefulness and ease of use in correspondence with the attitude and intention of the user (Davis, 1989, 1993).

As a continuation of this study on online learning, it is worth highlighting the research of Ibrahim et al. (2017), whose findings indicate that the intention to use e-learning is based on self-efficacy and ease of use, at the moment when the student considers themselves capable and skilled in using technology and also believes in its simplicity, which are conclusions that have already been drawn by Lee et al. (2011). However, this research by Ibrahim and colleagues points out that perceived usefulness has no impact on intention to use e-learning. This finding is further refuted by Nguyen et al. (2020), who found that students intend to choose online courses because they perceive them to be useful and help in the development of their professional skills; they also find them easy to use.

It is worth noting that open online courses (MOOCs), implemented as pioneers of online learning, are very popular among teachers and students, but also have a very high dropout rate. Wu and Chen (2017) analyse their acceptance using the TAM model, identifying perceived usefulness and attitude as relevant variables for the user's intention to use.

Based on the intention to use, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 7

(H7). Students' attitude towards learning will increase their intention to use technology.

The hypotheses are presented as a summary in Fig. 3.

Material and methodsSampleA type of non-probabilistic sampling known as convenience sampling has been used. In this type of sampling, instead of randomly selecting participants, those who are closest or easiest to recruit for the researcher are chosen. This sampling method has several benefits, such as speed, low cost, ease of implementation, and it is highly useful for exploratory studies. Additionally, it deals with the challenge of randomization, which is often difficult due to a large population size or when the researcher has limited resources, time and/or manpower (Etikan, Musa & Alkassim, 2016). Having said that, it does have significant limitations including sample bias, difficulty in generalizing results, and lack of diversity in terms of sample profile (age, sex, education level, etc.).

To obtain this data, an online survey was conducted among students from various Spanish public and private universities. A link to the survey was sent to university professors teaching undergraduate courses in different Spanish cities (Madrid, Andalusia, Castilla-La Mancha and Barcelona) so that they could distribute it among their students.

The respondents were second-, third- and fourth-year undergraduate students. All of them are students who have participated in face-to-face courses during the pandemic. The study was conducted on a sample of 313 students between September (26 September 2020) and November (28 November 2020).

All 313 respondents were students, 162 (52 %) of which were female and 151 (48 %) were male. Divided by field of study, 274 were studying for a degree in social sciences (Economics, Business Administration, Tourism, International Relations and Law), 28 in Engineering and 11 in other related fields.

Questionnaire designIn order to identify problems with the questions (ambiguous, confusing or unclear questions), the questionnaire was pre-tested and reviewed by five university professors with expertise in both methodology and related subject areas. This process allowed the authors of this study to:

- 1)

Ensure that the length of the questionnaire was appropriate.

- 2)

Ensure that the questions were correctly understood.

- 3)

Check that the questions addressed the correct topics and that the order was correct.

- 4)

Improve the reliability and validity of the test. Thanks to this phase some items deemed inappropriate were eliminated from the survey.

To minimise possible common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), several steps were taken. At the beginning of the questionnaire, a brief introduction ensured the confidentiality of the data collected. Depending on the structure of the information, the survey was presented in sections in which the questions were randomly ordered. Following the application of these measures, the common method bias was empirically examined using Harman's one-factor test. This found that 27.4 % of the variance was accounted for by a single factor, indicating the absence of bias in our study (Eichhorn, 2014).

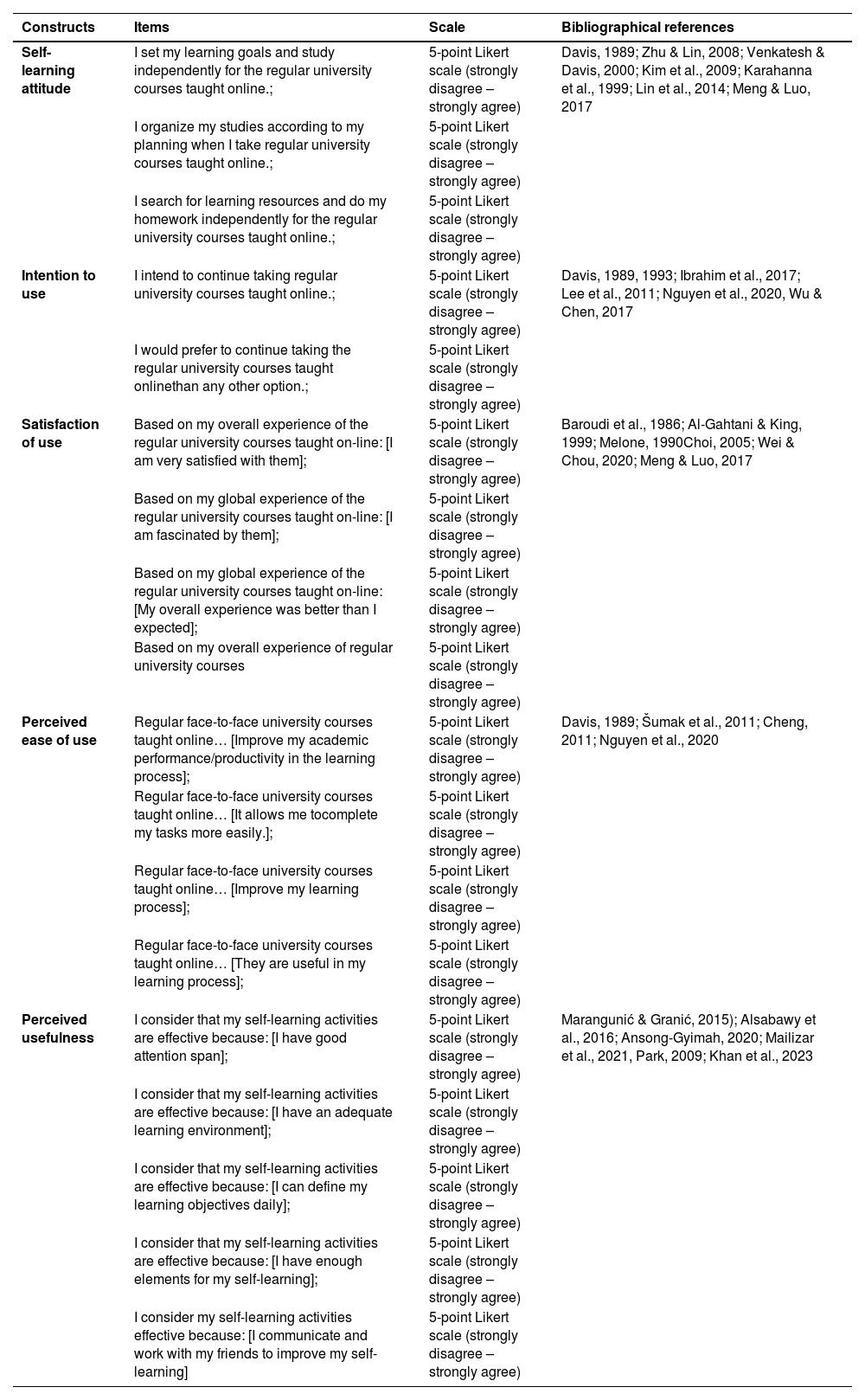

ScalesThe scales used for the present study have been tested and used in other research. Table 1 provides information on the number of items on the scales used and literature references indicating where these scales have been previously used (Table 1).

Questionnaire items, scales and corresponding bibliographical references.

| Constructs | Items | Scale | Bibliographical references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-learning attitude | I set my learning goals and study independently for the regular university courses taught online.; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | Davis, 1989; Zhu & Lin, 2008; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Kim et al., 2009; Karahanna et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2014; Meng & Luo, 2017 |

| I organize my studies according to my planning when I take regular university courses taught online.; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| I search for learning resources and do my homework independently for the regular university courses taught online.; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Intention to use | I intend to continue taking regular university courses taught online.; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | Davis, 1989, 1993; Ibrahim et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2011; Nguyen et al., 2020, Wu & Chen, 2017 |

| I would prefer to continue taking the regular university courses taught onlinethan any other option.; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Satisfaction of use | Based on my overall experience of the regular university courses taught on-line: [I am very satisfied with them]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | Baroudi et al., 1986; Al-Gahtani & King, 1999; Melone, 1990Choi, 2005; Wei & Chou, 2020; Meng & Luo, 2017 |

| Based on my global experience of the regular university courses taught on-line: [I am fascinated by them]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Based on my global experience of the regular university courses taught on-line: [My overall experience was better than I expected]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Based on my overall experience of regular university courses | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Perceived ease of use | Regular face-to-face university courses taught online… [Improve my academic performance/productivity in the learning process]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | Davis, 1989; Šumak et al., 2011; Cheng, 2011; Nguyen et al., 2020 |

| Regular face-to-face university courses taught online… [It allows me tocomplete my tasks more easily.]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Regular face-to-face university courses taught online… [Improve my learning process]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Regular face-to-face university courses taught online… [They are useful in my learning process]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| Perceived usefulness | I consider that my self-learning activities are effective because: [I have good attention span]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | Marangunić & Granić, 2015); Alsabawy et al., 2016; Ansong-Gyimah, 2020; Mailizar et al., 2021, Park, 2009; Khan et al., 2023 |

| I consider that my self-learning activities are effective because: [I have an adequate learning environment]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| I consider that my self-learning activities are effective because: [I can define my learning objectives daily]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| I consider that my self-learning activities are effective because: [I have enough elements for my self-learning]; | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) | ||

| I consider my self-learning activities effective because: [I communicate and work with my friends to improve my self-learning] | 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

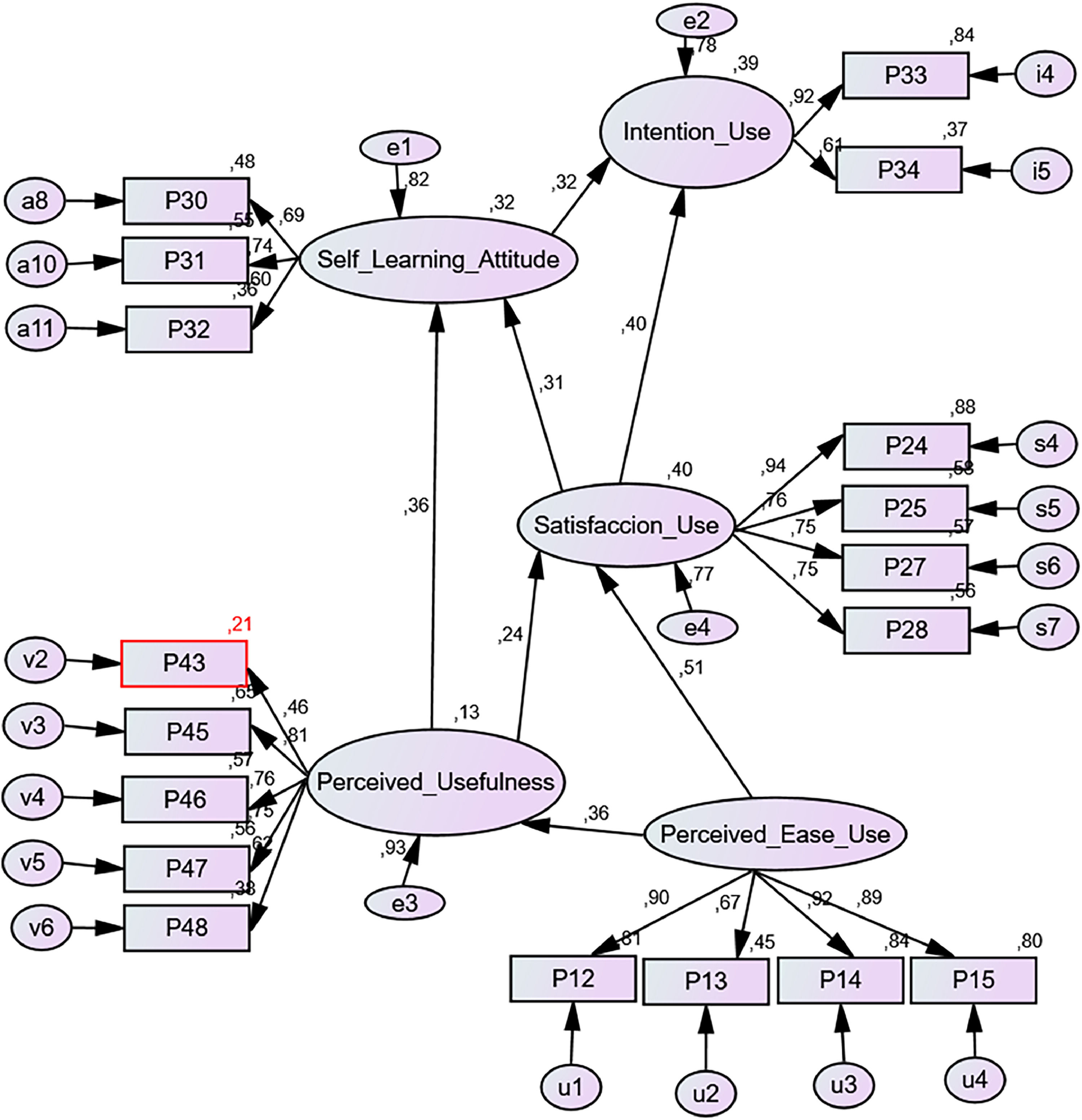

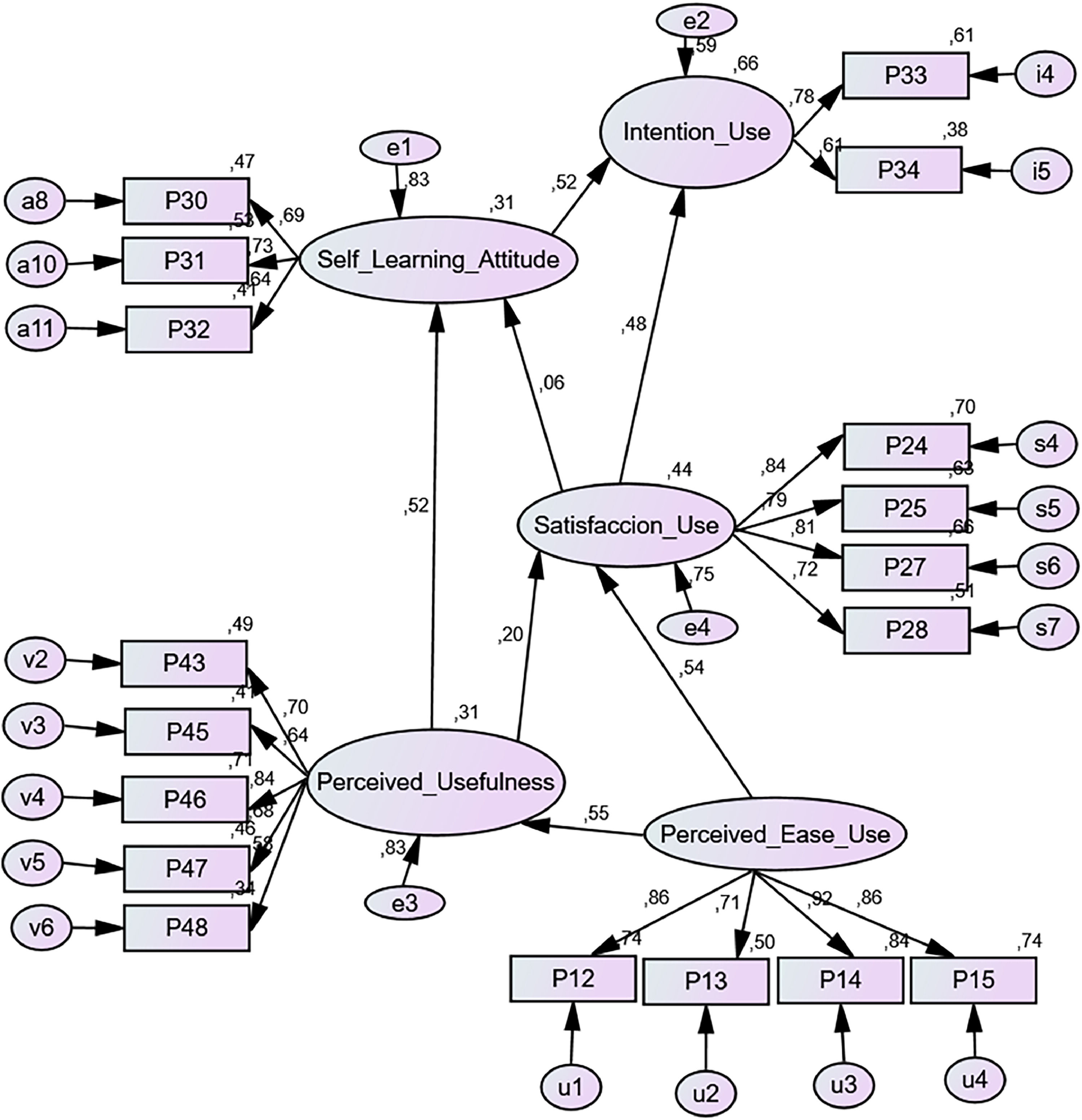

The analysis was conducted through structural equation modelling (SEM) using AMOS software (version 23) (see Fig. 4 and 5). In recent years, this methodology has been frequently used in the education sector (Álvarez & Dicovskiy 2022; Cano-Ibarra et al., 2022; Samperio-Pacheco, 2019).

Through this system the relationships between constructs can be observed, as well as the predictive power of the model. To draw up the constructs, an exhaustive review of the literature has been carried out, which has provided the authors of this study with a broad knowledge of the items included in each of them as well as the scales used (see Table 1).

To obtain results, an analysis consisting of three significant stages was carried out: 1) determining a hypothetical relationship between the variables; 2) conducting an exploratory factor analysis to determine the variance and covariance; 3) conducting a confirmatory factor analysis to identify the most significant relationships within the model.

The final stage consists of interpreting the model. Three distinct stages can be distinguished: 1) an estimation of the levels of reliability as well as convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model; 2) a calculation of the structural model; and 3) an estimation of the gender differences in the model.

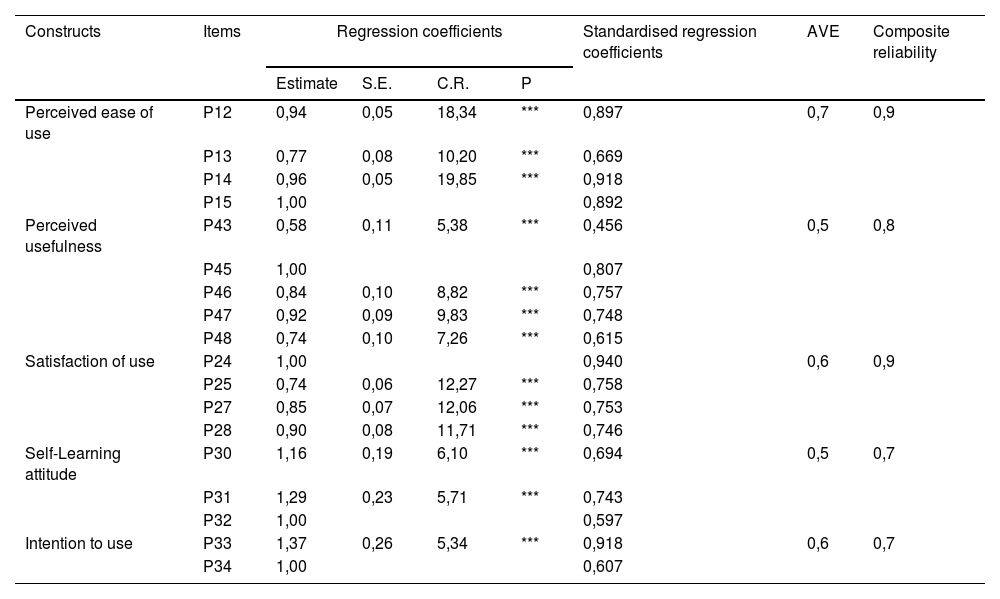

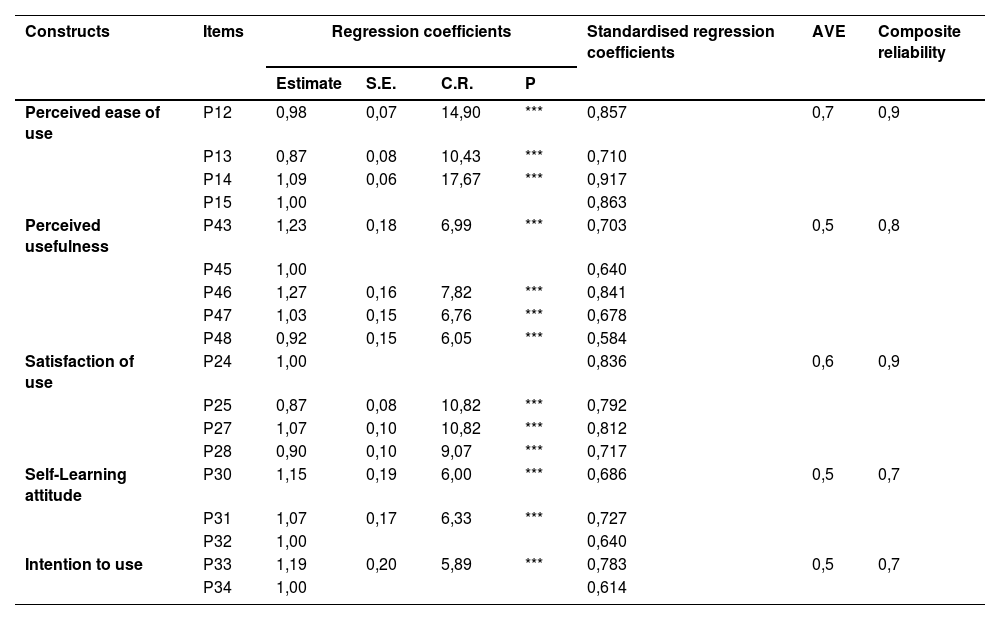

ResultsModel measurementsThe constructs have been formed by adapting scales similar to those already used in other research studies and which have been previously validated (see Table 1).

Firstly, the reliability of the indicator will be further analysed by looking at the factor loadings (convergent validity), which can be defined as the correlation between the observed variables and the construct in which they are included.

Taking into account the recommendations of the existing literature, the reliability of the factor is obtained when a factor loading greater than ± 0.3 is established, which for some authors is the minimum acceptable value (Hair et al., 2010). This criterion is achieved in both the female and male models. The lowest value found is found for item P.43 of the construct "perceived usefulness" in the case of the model analysing the female group (0.46). Even so, it is within the parameters accepted by the scientific literature in the field of statistics (see Tables 2 and 3). The significance level of the factor loadings has also been checked. As can be seen in the table, all are significant (p < 0.001).

Observed variables and construct reliability. Females.

| Constructs | Items | Regression coefficients | Standardised regression coefficients | AVE | Composite reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||||

| Perceived ease of use | P12 | 0,94 | 0,05 | 18,34 | *** | 0,897 | 0,7 | 0,9 |

| P13 | 0,77 | 0,08 | 10,20 | *** | 0,669 | |||

| P14 | 0,96 | 0,05 | 19,85 | *** | 0,918 | |||

| P15 | 1,00 | 0,892 | ||||||

| Perceived usefulness | P43 | 0,58 | 0,11 | 5,38 | *** | 0,456 | 0,5 | 0,8 |

| P45 | 1,00 | 0,807 | ||||||

| P46 | 0,84 | 0,10 | 8,82 | *** | 0,757 | |||

| P47 | 0,92 | 0,09 | 9,83 | *** | 0,748 | |||

| P48 | 0,74 | 0,10 | 7,26 | *** | 0,615 | |||

| Satisfaction of use | P24 | 1,00 | 0,940 | 0,6 | 0,9 | |||

| P25 | 0,74 | 0,06 | 12,27 | *** | 0,758 | |||

| P27 | 0,85 | 0,07 | 12,06 | *** | 0,753 | |||

| P28 | 0,90 | 0,08 | 11,71 | *** | 0,746 | |||

| Self-Learning attitude | P30 | 1,16 | 0,19 | 6,10 | *** | 0,694 | 0,5 | 0,7 |

| P31 | 1,29 | 0,23 | 5,71 | *** | 0,743 | |||

| P32 | 1,00 | 0,597 | ||||||

| Intention to use | P33 | 1,37 | 0,26 | 5,34 | *** | 0,918 | 0,6 | 0,7 |

| P34 | 1,00 | 0,607 | ||||||

*** p < 0.001.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Observed variables and construct reliability. Males.

| Constructs | Items | Regression coefficients | Standardised regression coefficients | AVE | Composite reliability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||||

| Perceived ease of use | P12 | 0,98 | 0,07 | 14,90 | *** | 0,857 | 0,7 | 0,9 |

| P13 | 0,87 | 0,08 | 10,43 | *** | 0,710 | |||

| P14 | 1,09 | 0,06 | 17,67 | *** | 0,917 | |||

| P15 | 1,00 | 0,863 | ||||||

| Perceived usefulness | P43 | 1,23 | 0,18 | 6,99 | *** | 0,703 | 0,5 | 0,8 |

| P45 | 1,00 | 0,640 | ||||||

| P46 | 1,27 | 0,16 | 7,82 | *** | 0,841 | |||

| P47 | 1,03 | 0,15 | 6,76 | *** | 0,678 | |||

| P48 | 0,92 | 0,15 | 6,05 | *** | 0,584 | |||

| Satisfaction of use | P24 | 1,00 | 0,836 | 0,6 | 0,9 | |||

| P25 | 0,87 | 0,08 | 10,82 | *** | 0,792 | |||

| P27 | 1,07 | 0,10 | 10,82 | *** | 0,812 | |||

| P28 | 0,90 | 0,10 | 9,07 | *** | 0,717 | |||

| Self-Learning attitude | P30 | 1,15 | 0,19 | 6,00 | *** | 0,686 | 0,5 | 0,7 |

| P31 | 1,07 | 0,17 | 6,33 | *** | 0,727 | |||

| P32 | 1,00 | 0,640 | ||||||

| Intention to use | P33 | 1,19 | 0,20 | 5,89 | *** | 0,783 | 0,5 | 0,7 |

| P34 | 1,00 | 0,614 | ||||||

*** p < 0.001.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Secondly, it is necessary to test the reliability of the construct by analysing the composite reliability or internal consistency. A value accepted by the literature as valid is 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978). In this study, all constructs are reliable because they exceed this value to a greater or lesser extent (see Tables 2 and 3).

Thirdly, it is recommended that a convergent validity analysis be carried out using the AVE (Average Variance Extracted) indicator. Values above 0.5 are recommended, although a range of 0.49 to 0.76 is also acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This value is exceeded for all constructs. Therefore, convergent validity is accepted (see Tables 2 and 3).

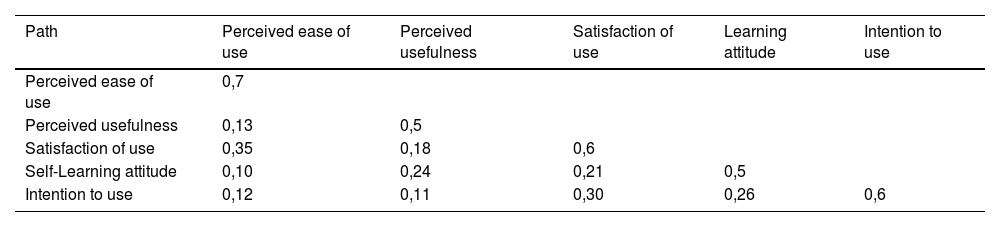

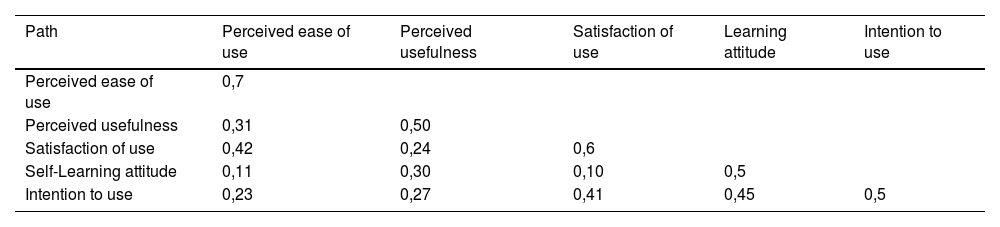

Finally, it is important to analyse the discriminant validity. The aim of this analysis is to check whether a given construct measures a concept differently from other constructs. This means that the variance that a construct shares with its indicators is greater than the variance it may share with other constructs in the model. For this purpose, it is recommended that the AVE of each construct be greater than the square of the correlations between this construct and each of the other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In this case, the constructs meet this condition, so discriminant validity is accepted (see Tables 4 & 5).

Discriminant validity. Females.

| Path | Perceived ease of use | Perceived usefulness | Satisfaction of use | Learning attitude | Intention to use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived ease of use | 0,7 | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | 0,13 | 0,5 | |||

| Satisfaction of use | 0,35 | 0,18 | 0,6 | ||

| Self-Learning attitude | 0,10 | 0,24 | 0,21 | 0,5 | |

| Intention to use | 0,12 | 0,11 | 0,30 | 0,26 | 0,6 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Discriminant validity. Males.

| Path | Perceived ease of use | Perceived usefulness | Satisfaction of use | Learning attitude | Intention to use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived ease of use | 0,7 | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | 0,31 | 0,50 | |||

| Satisfaction of use | 0,42 | 0,24 | 0,6 | ||

| Self-Learning attitude | 0,11 | 0,30 | 0,10 | 0,5 | |

| Intention to use | 0,23 | 0,27 | 0,41 | 0,45 | 0,5 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

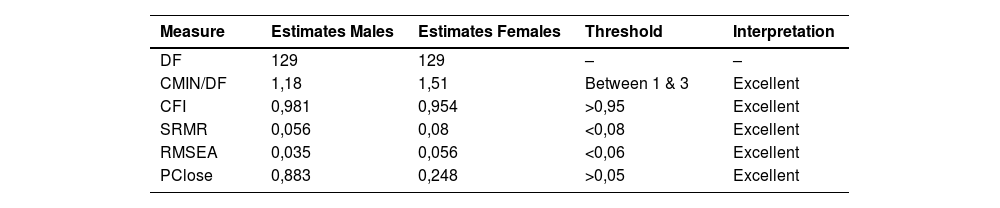

Once the reliability of the indicators and constructs has been assessed, the next step is to build the models. Once built, it is necessary to check the overall fit to the observed data. These indices are used to assess the goodness-of-fit of the model and the accuracy of the data in structural equation analysis.

It is important to note that a single index alone does not provide a complete assessment of model fit, so it is recommended to evaluate models using several indices in parallel. In this way, a completer and more accurate picture of the model fit is achieved.

For this study, four commonly used indices in this type of methodologies and offered by the Amos statistical package will be leveraged:

- a)

CMIN (Chi-Square Minimum Discrepancy): The CMIN index, also known as chi-square minimum discrepancy, measures the disparities between the covariances and the estimated covariances in the structural equation model. A lower value of CMIN indicates a better fit for the model.

- b)

CFI (Comparative Fit Index): CFI gauges incremental fit by comparing the proposed model with an unconstrained baseline model (null model). CFI values range between 0 and 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates a better model fit. A CFI value greater than 0.95 is generally considered an acceptable fit for the model.

- c)

RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation): RMSEA evaluates the overall fit of the proposed model to the population. It indicates the degree of fit of the covariances and provides a measure of how well the model fits the population. RMSEA values range between 0 and 1, where a value <0.06 is considered an excellent fit.

- d)

SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual): SRMR assesses the difference between the observed correlations and the correlations estimated by the model. With values ranging from 0 to 1, an SRMR value of <0.08 generally indicates a good model fit.

The results obtained indicate that the goodness of fit of the model for both females and males are within the recommended limits (Table 6).

Model fit.

| Measure | Estimates Males | Estimates Females | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF | 129 | 129 | – | – |

| CMIN/DF | 1,18 | 1,51 | Between 1 & 3 | Excellent |

| CFI | 0,981 | 0,954 | >0,95 | Excellent |

| SRMR | 0,056 | 0,08 | <0,08 | Excellent |

| RMSEA | 0,035 | 0,056 | <0,06 | Excellent |

| PClose | 0,883 | 0,248 | >0,05 | Excellent |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

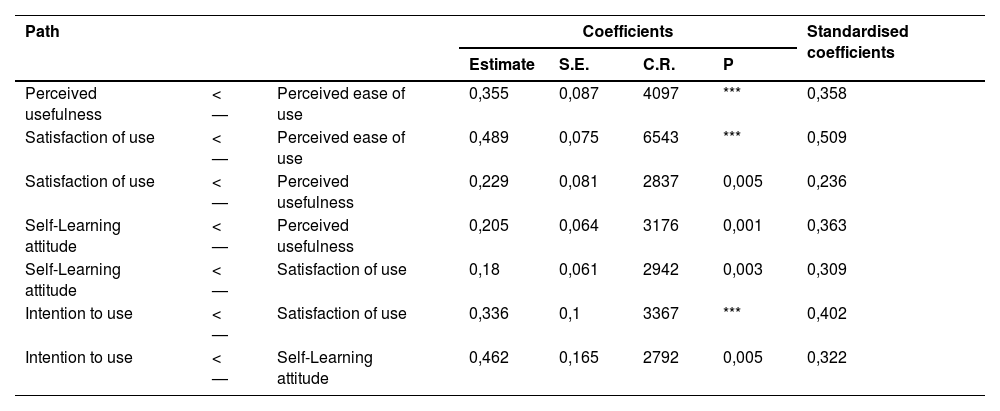

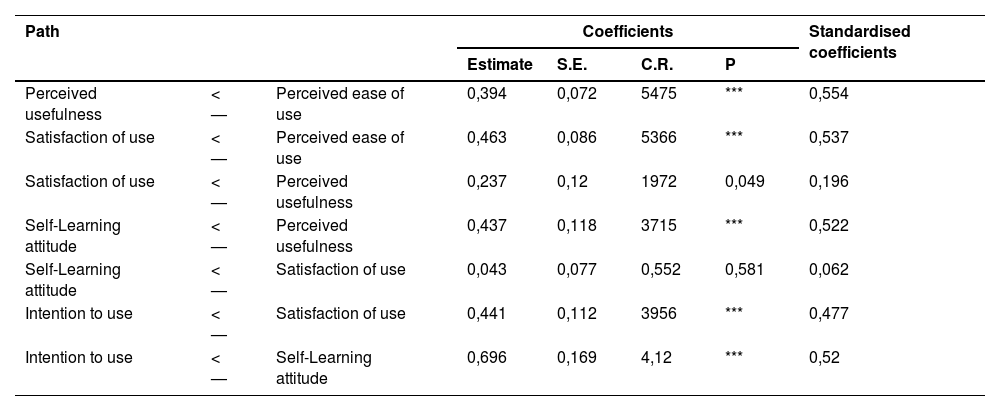

In Tables 7 and 8 the results of the models for both females and males can be analysed and the first five established hypotheses can be accepted or rejected.

Model results. Females.

| Path | Coefficients | Standardised coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | <— | Perceived ease of use | 0,355 | 0,087 | 4097 | *** | 0,358 |

| Satisfaction of use | <— | Perceived ease of use | 0,489 | 0,075 | 6543 | *** | 0,509 |

| Satisfaction of use | <— | Perceived usefulness | 0,229 | 0,081 | 2837 | 0,005 | 0,236 |

| Self-Learning attitude | <— | Perceived usefulness | 0,205 | 0,064 | 3176 | 0,001 | 0,363 |

| Self-Learning attitude | <— | Satisfaction of use | 0,18 | 0,061 | 2942 | 0,003 | 0,309 |

| Intention to use | <— | Satisfaction of use | 0,336 | 0,1 | 3367 | *** | 0,402 |

| Intention to use | <— | Self-Learning attitude | 0,462 | 0,165 | 2792 | 0,005 | 0,322 |

*** p < 0.001.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Model results. Males.

| Path | Coefficients | Standardised coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | <— | Perceived ease of use | 0,394 | 0,072 | 5475 | *** | 0,554 |

| Satisfaction of use | <— | Perceived ease of use | 0,463 | 0,086 | 5366 | *** | 0,537 |

| Satisfaction of use | <— | Perceived usefulness | 0,237 | 0,12 | 1972 | 0,049 | 0,196 |

| Self-Learning attitude | <— | Perceived usefulness | 0,437 | 0,118 | 3715 | *** | 0,522 |

| Self-Learning attitude | <— | Satisfaction of use | 0,043 | 0,077 | 0,552 | 0,581 | 0,062 |

| Intention to use | <— | Satisfaction of use | 0,441 | 0,112 | 3956 | *** | 0,477 |

| Intention to use | <— | Self-Learning attitude | 0,696 | 0,169 | 4,12 | *** | 0,52 |

*** p < 0.001.

Source: Prepared by the authors

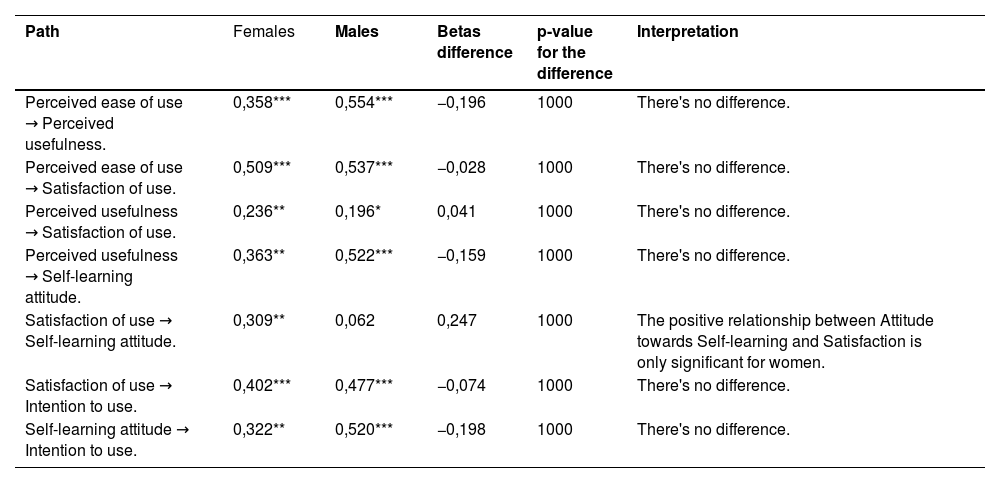

Results of the multi-group analysisIn order to analyse whether there were differences in the relationships of the constructs between the two segments, the results were compared with the aim of finding significant differences. By applying a multi-group analysis with the Amos statistical programme, the results found in Table 9 were observed.

Multigroup analysis.

| Path | Females | Males | Betas difference | p-value for the difference | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived ease of use → Perceived usefulness. | 0,358*** | 0,554*** | −0,196 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

| Perceived ease of use → Satisfaction of use. | 0,509*** | 0,537*** | −0,028 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

| Perceived usefulness → Satisfaction of use. | 0,236** | 0,196* | 0,041 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

| Perceived usefulness → Self-learning attitude. | 0,363** | 0,522*** | −0,159 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

| Satisfaction of use → Self-learning attitude. | 0,309** | 0,062 | 0,247 | 1000 | The positive relationship between Attitude towards Self-learning and Satisfaction is only significant for women. |

| Satisfaction of use → Intention to use. | 0,402*** | 0,477*** | −0,074 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

| Self-learning attitude → Intention to use. | 0,322** | 0,520*** | −0,198 | 1000 | There's no difference. |

p < 0,100* p < 0,050** p < 0,010***.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

This study validates the TAM model for the relationship that students establish between technology and self-learning. Positive relationships are observed between all the constructs of the model– ease of use, satisfaction, attitude, intention and usefulness– as demonstrated in the proposed hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6 and H7). Applying reliability indices confirms the significance of these relationships.

Therefore, the objective of the study is addressed, establishing that technology is a catalyst for the promotion of learning in men and women. However, while the need for learning is a similar trigger and/or motivation in both sexes, applying the external variable—gender–to the TAM model, reveals differences in the relationship between satisfaction and the attitude towards self-learning for men and women (H5). This reaffirms the robustness of the TAM model.

The main finding after carrying out the multigroup analysis is that, for women, online teaching is a way to promote self-learning, since they express satisfaction to continue learning by exploiting the online resources that are available to them. These findings are consistent with Liu and Zhang's study (2023), which focuses on adult students over 50 years old and highlights the relevance of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. These conclusions indicate that online teaching has the potential to encourage female university students to be more self-directed in their studies.

For their part, men also rely on technology but do not acquire the feeling of self-learning despite consuming resources to the same degree as women. As indicated by H5, where satisfaction with learning leads to the development of a positive attitude towards self-learning. Therefore, online teaching is a way to promote self-learning specifically in women and this, in turn, causes a greater interest in online teaching. As H5 demonstrates, satisfaction with the learning process leads to students developing a positive attitude towards self-learning.

ConclusionsThis study corroborates the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in the context of the relationship that students develop between technology and self-learning. Favorable associations are identified among all the constructs of the model, namely, ease of use, satisfaction, attitude, intention, and usefulness, as confirmed by the stated hypotheses.

The model focused on a single external variable, as the study's purpose is to determine if there are significant differences based on gender. The conclusions obtained suggest that online education has the potential to motivate female university students to adopt a more self-directed approach to their studies. This is because it generates a sense of satisfaction that drives the continuity of learning, which is connected to the availability of digital resources. In contrast, while male students also make use of technology, they do not experience the same sense of self-learning, despite using the resources to the same extent as women.

The practical implications of this study involve bringing the results into the classroom through training aimed at fostering real-world skills. Technology allows instructors to segment students into groups and offer them a more personalized experience. This teaching practice is not only intended to achieve greater student satisfaction with the programs but also to promote, with the help of their instructor, greater autonomy and commitment among men with the guidance of the tutor.

This study does present certain limitations worth highlighting, which are intended to be addressed in future research. As mentioned earlier, one of these limitations is related to sample bias, the difficulty of extrapolating the results, and the lack of diversity in the participants' profiles, in terms of age, sex, and educational level, among other factors.

Another limitation found in conducting the study is the high proportion of young people in the sample, who tend to show a reserved attitude towards their habits and consider the process of completing questionnaires monotonous.

Regarding the literature review, there is a scarcity of studies that address learning from a gender perspective, which represents a limitation for enriching the discussion.

Regarding limitations, although the sample is representative, expanding it to include a greater number of autonomous communities could ensure greater geographical breadth. Additionally, this study could be expanded to include diverse knowledge groups. Broadening the study to include fields of study beyond the social sciences such as Engineering and Humanities would provide more comprehensive insights into gender and representation.

The future lines of research that have arisen from this study are multidisciplinary. In the educational field, the authors of this study propose to continue focusing on each of the constructs that make up the TAM model and to deepen the adoption of students in the different teaching modalities adopted in recent times (e-learning, b-learning, m-learning and transformational learning) with the aim of comparing behavior and understanding their application. Additionally, continued research on active learning methodologies such as gamification should be done and applied to this same model.

In addition, expanding the group of external variables of the TAM model is proposed in order to determine if, besides gender, other factors such as age or the field of study of students may lead to behavioral differences that allow for offering an experience tailored to the students' abilities, who could be divided into groups.

Accordingly, beyond the educational sphere, the application of the TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior) model is proposed to determine the intention to consume technology through a multigroup analysis, which would allow for further behavioural comparisons between men and women.

Availability of data and materialsThe datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJuan Antonio Márquez García: Conceptualization. Cristina Gallego Gómez: Methodology. Alicia Tapia López: Investigation. Matthew J. Schlosser: Supervision, Conceptualization.

Not applicable