Entrepreneurship is a crucial driver of economic growth, necessitating the development of effective entrepreneurial ecosystems. However, there are significant gaps in the literature regarding the structured assessment of these ecosystems. This study addresses three main research gaps: the lack of structured evaluation methods, the need for a comprehensive analysis of ecosystem challenges from various perspectives, and the identification of critical factors essential for ecosystem growth. To bridge these gaps, the research introduces the Hierarchical Decision Model (HDM) as a universal assessment framework that can be adapted to different cities for creating effective entrepreneurial environments. The research methodology involved formulating perspectives and criteria through literature reviews and expert interviews. These perspectives and criteria were validated by subject matter experts and quantified by other experts to assign relative weights to each. Desirability curves were developed to measure these criteria, scored by experts. The practical applicability of the HDM was demonstrated through a case study of Riyadh, showcasing the model's effectiveness in real-world scenarios. Key findings include the identification and ranking of twenty critical criteria across five main perspectives, along with the development of desirability curves for each criterion. This provides a practical, easy-to-implement evaluation tool for policymakers. The contributions of this research are multifaceted: it introduces HDM to the field of entrepreneurship ecosystem assessment, offers a practical model for ecosystem performance measurement, and presents a framework for policy improvements. Additionally, it highlights the importance of continuous model refinement and the inclusion of diverse case studies for broader validation. Future research should focus on expanding the model to include sub-models for different regions and stages of startups’ development, ensuring its ongoing relevance and applicability. The findings show the most effective factors (perspectives and criteria) in developing entrepreneurial ecosystems and provide a method to measure the level of each criterion without requiring deep knowledge of the methodology, making it easier to implement the model in any ecosystem with any experts. The research offers an explicit case study evaluation of Riyadh's entrepreneurial ecosystem and provides recommendations for improvement areas. This study contributes to the technology management body of knowledge, particularly in the context of entrepreneurship ecosystems, presenting a universal assessment model for measuring ecosystem performance in any city. It creates an evaluation and improvement framework for policymakers to develop entrepreneurial ecosystems in their cities, ensuring continuous relevance and practicality through ongoing refinement and diverse case study applications.

Entrepreneurship is a crucial driver of economic growth, as it transforms technical knowledge into products and services, driving innovation and addressing economic inefficiencies (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Kirzner, 1997). Entrepreneurs, startups, and SMEs are vital to the global economy, contributing 96 % of economic activity (ITU report). Despite the importance of entrepreneurial ecosystems, which have emerged as a significant concept in the past two decades (Stam, 2015), there is a notable lack of comprehensive methods for evaluating these ecosystems effectively. Entrepreneurial ecosystem is a relatively new concept that has started to emerge within the past twenty years (Stam, 2015). Technology transfer involves moving knowledge or technology between institutions and encompasses the associated costs (Bolatan et al., 2022). It is linked with innovation management and produces both tangible and intangible outcomes. While traditional methods like patenting, licensing, and start-ups are frequently discussed, alternative methods such as consulting, training, and exchange programs also play significant roles (Kim & Daim, 2014). Technology transfer enhances the efficiency of systems, products, and services, thereby supporting entrepreneurship (Amaros et al., 2019; Cunningham et al., 2019; Boh et al., 2016; Cassia et al., 2014).

In entrepreneurial ecosystems, technology transfer is crucial because it affects regional innovation mechanisms and the effectiveness of innovation processes. Efficient conversion of ideas into innovative products is essential for the success of these ecosystems (Audretsch et al., 2019). University-based technology transfer offices, which promote patenting and entrepreneurship, play a key role in this process. Boh et al. (2016) highlight that integrating traditional economic goals with technology transfer activities, such as patents and spinoffs, is vital for academic entrepreneurship. Cassia et al. (2014) found that knowledge transfer stakeholders enhance scientific research performance, while Bolzani et al. (2021) focused on the role of technology transfer offices in entrepreneurial education. Wright (2014) examined technological entrepreneurship through the lens of technology and knowledge transfer among various entities.

This research aims to develop an assessment model for entrepreneurial ecosystems, given the strong relationship between technology transfer and entrepreneurship (Bolzani et al., 2021; Wright, 2014).

Entrepreneurial ecosystems are essential for fostering business growth and enhancing economic development. However, current research indicates that the study of these ecosystems is still in its nascent stages. Limited research exists on structured assessment methods, evaluation of ecosystem challenges from various perspectives, and identification of critical growth factors. Addressing these gaps is crucial as it influences not only the effectiveness of ecosystems but also the broader quality of life.

The literature review and the gap analysis led to the following research gaps:

- 1.

Structured Assessment Methods: There is insufficient research on systematic methods to evaluate entrepreneurial ecosystems.

- 2.

Perspective-Based Evaluation: Existing studies lack comprehensive analysis of ecosystem challenges from multiple viewpoints.

- 3.

Critical Factors: There is a need for research to define and prioritize the key factors that drive the growth of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

- 4.

Fig. 1 shows the formulation of the research objectives, and the questions based on these research gaps.

This study aims to develop a universal assessment model for entrepreneurial ecosystems, addressing the identified research gaps. By utilizing the Hierarchical Decision Model (HDM), the research intends to provide a structured framework for evaluating ecosystem effectiveness. This model will facilitate the identification and measurement of critical factors, offering practical insights for policymakers and contributing to the advancement of both theoretical and managerial knowledge in the field of entrepreneurship.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: Section "Literature Review" introduces entrepreneurial ecosystems and reviews relevant literature. Section "Methodology and Results" details the methodology and results of the model development. Section "Case Study Application" presents a case study application of the model. Finally, Sections "Discussion and Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research" provide conclusions, discuss research contributions, acknowledge limitations, and suggest future research directions.

Literature reviewEntrepreneurial ecosystemsThe literature review of entrepreneurial ecosystems approach focuses on the external business environment like other established approaches such as clusters, innovation systems and learning regions, and industrial districts. The entrepreneurial ecosystem approach considers entrepreneurs to be the leaders and the center of the system creation rather than only considering them as results of the system. This literature lacks depth and does not highlight academic audiences as much as practitioners (Stam, 2015). The role of the social context in enabling entrepreneurship appears to be present in the literature review of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Acs et al., 2014; Neck et al., 2004; Sternberg, 2007). Spigel (2017) found that the literature of entrepreneurial ecosystems includes research on “clusters (Delgado et al., 2010; Marshall, 1920; Porter, 1998), economic geography (Feldman, 2001; Malecki, 1997), innovations systems (Cooke et al., 1997; Fritsch, 2001; Urbano et al., 2019), social capital (Westlund & Bolton, 2003), and networks (Sorenson & Stuart, 2001; Stuart & Sorenson, 2003)”. Ecosystems have ambiguous structures (Ritala & Gustafsson, 2018). The entrepreneurial ecosystem includes the function of many social, political, economic, and cultural activities that support the growth of both new and existing entrepreneurs in the broader context of entrepreneurship (Radinger-Peer et al., 2018). To create and grow a firm, entrepreneurship requires both an initiator (an individual who has an idea to launch a business) and an organizational setting (Roundy et al., 2018).

According to Alvedalen and Boschma (2017), industrial clusters are at the center of innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems, where regional and local factors affect the combined capacities of local agents. Whereas the economic and technological dimensions of entrepreneurial ecosystems explain how value is created, the societal dimension relates to value distribution (Audretsch et al., 2019). According to bibliometric data, the term entrepreneurial ecosystem is now more commonly used than other ideas like settings for entrepreneurship, which similarly emphasize the systems, networks, and cultures that support entrepreneurs (Malecki, 2018). Researchers have conceptualized and measured entrepreneurial ecosystems as geographic regions since research on entrepreneurial ecosystems is based on natural phenomena (Liguori et al., 2019).

The approach of entrepreneurial ecosystems has recently emerged within the last decade (Stam, 2015). Culture, social networks, universities, investment capital, and economic policies that support technology innovation-based ventures are all elements of ecosystems. These elements are seen in academia (Acs et al., 2014; Feldman et al., 2005; Burkholder & Hulsink, 2022), policy (Isenberg, 2010; Jones, 2013), and well known entrepreneurship literature (Feld, 2012; Hwang & Horowitt, 2012) as an approach to develop strong economies built upon entrepreneurial innovation. However, the research in entrepreneurial ecosystems is still in the early stages. Entrepreneurial ecosystems have led to an economic rise in countries like China, the United States, Argentina, India, and Mexico despite the unstable social and economic states of some of these countries (Bernardez & Mead, 2009). Individuals and institutions are the main elements that shape the entrepreneurship ecosystem (Barati et al., 2017). The ecosystem approach has been addressed in the fields of business, entrepreneurship, and innovation. These ecosystems consist of elements that interact with each other forming complex systems (Maysami et al., 2019; Hiebl and Pielsticker, 2023). The endurance of high-growth entrepreneurship within regions has come to be explained by the concept of entrepreneurial ecosystems, which has gained popularity. Ecosystems are still an immature theoretical idea, making it challenging to comprehend how they are structured and how they affect the entrepreneurship process. Ecosystems are made up of cultural, social, and material characteristics that offer resources and advantages to businesspeople, and t the connections between these characteristics regenerate the ecosystem (Spigel, 2017). Other businesses and organizations, many of which have specialized and skilled staff, increase the ecosystem's competitiveness (Spigel & Harrison, 2018).

Wurth et al. (2021) suggest a transdisciplinary research program of entrepreneurial ecosystems separated into four research streams (context, structure, micro-foundations, and complex systems) and four cross-sectional themes due to the complexity of the entrepreneurial ecosystem (methodologies and measurements, theory, critical research, and transdisciplinary research). A brief and recent definition of entrepreneurship ecosystem is “enabling entrepreneurship within a region through a group of interdependent factors” (Stam & Spigel, 2016). Entrepreneurial ecosystems are defined as the elements that enable productive entrepreneurship within a specific field (Baumol, 1990). The concept of entrepreneurial ecosystems has two parts. The first is “entrepreneurial”, which refers to exploring the opportunity of creating new goods or services, followed by evaluation, and then taking actions (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). The second part is “ecosystem”, which is defined as the “system, or a group of interconnected elements, formed by the interaction of a community of organisms with their environment” (Kreuzer et al., 2018). Other definitions focus on different aspects such as talented workers, lawyers, large local firms, or universities that take the role of talents supporters (Neck et al., 2004; Patton & Kenney, 2005; Spilling, 1996). Isenberg (2010) and the Jones (2013) identified the essential elements of ecosystems with the presence of human capital, mentorship and supportive programs, financing, local and international access to markets, solid organizational framework, and universities. The combination of short/long education and narrow/broad human labor research can improve the roadmap of entrepreneurship ecosystems by incorporating innate skills and by conceptualizing four generic archetypes: the local entrepreneur, the global entrepreneur, the incremental entrepreneur, and the radical entrepreneur. (Østergaard & Marinova, 2018).

Huang et al. (2023) explores how individual and national factors interact to foster opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship, using a framework based on the national system of entrepreneurship. Analyzing 39 countries with fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis, it finds that while institutional or cognitive elements are not essential for high levels of opportunity or necessity entrepreneurship, improving entrepreneurs' ability perceptions is universally beneficial. The study identifies optimal pathways that integrate institutional and individual factors to enhance both types of entrepreneurship and narrow international disparities in entrepreneurial activities.

Attributes and models of entrepreneurial ecosystemIsenberg (2010) concluded that there are nine attributes that leaders should follow when building an entrepreneurial ecosystem rather than an exact formula. These attributes have led to build a six domains ecosystem that includes: policy, finance, culture, support, human capital, and markets. Isenberg (2011) This ecosystem intersects with the previous nine attributes by Isenberg (2010) and the eight pillars by Jones (2013). These pillars include resources such as human capital, finance, and services. Based on work by Stam (2015), a new entrepreneurial ecosystem model has been developed. This model includes four main levels: framework conditions, systemic conditions, outputs, and outcomes. The level of systemic conditions is the core level in this ecosystem. It includes networks of entrepreneurs, leadership, finance, talent, knowledge, and support services. A successful ecosystem could be seen where these elements are available with a cohesive interaction. The network of entrepreneurs makes knowledge and information sharing an easier process (Caiazza et al., 2020). Leaders help in guiding entrepreneurs inside the ecosystem by relying on their experiences and influence in their regions. Finance is the third element that is provided by different types of investors (Kerr & Nanda, 2009). A much more important element is the presence of talented individuals (Acs & Armington, 2004; Lee et al., 2004; Qian et al., 2013). Knowledge is another important element that makes the ecosystem much more effective (Audretsch & Lehmann, 2005). According to Yi et al. (2021), an entrepreneurial environment does not emerge automatically because it typically emerges in places with an established knowledge base that employs a significant number of scientists and engineers. It has been demonstrated that firms can acquire knowledge resources that have been spilled outward from other knowledge subjects through direct or indirect communication and interaction. Individuals in the organization are responsible for knowledge, and their knowledge activities are critical to the application of knowledge utilities. Another conceptual framework of the entrepreneurial ecosystem was created by considering eight different factors: moral, financial, technology, market, social, network, government and environmental (Suresh & Ramraj, 2012).

Critical factors of entrepreneurial ecosystemsPolicyPolicy is defined as the set of government guidelines and regulations that control the entrepreneurial activities (Goel & Nelson, 2023; Management Study Guide, 2021). The systemic approach of the entrepreneurship ecosystem provides an opportunity for policy makers to boost the growth-oriented entrepreneurship by developing policies and implementing strategies (Brown & Mason, 2017; Lösften et al., 2022). Nicotra et al. (2018) defined the entrepreneurial ecosystem as the confluence of social, political, economic, and cultural factors in a region that fosters the growth and development of innovative startups, and that motivates new business owners and other actors to take the risk of founding, funding, and otherwise assisting high-risk enterprises. In the free market economy, entrepreneurship is a key driver of innovation and a crucial tool for improving the effectiveness of resource allocation (Acs et al., 2014). According to Nicotra et al. (2018), the ease of beginning a firm, the business-friendliness of rules, tax incentives, and access to infrastructure are specific indicators in the policy domain. As a result policy makers have been supporting a high level of entrepreneurial activity, which results in economic growth and job creation (Audretsch et al., 2015). Unfortunately, little is understood about how an entrepreneurial ecosystem functions and what the associated policy issues are (Autio & Levie, 2017). The idea of entrepreneurial ecosystems (EE) as productive structures that include intricate networks of interaction that boost economic agents' competitive abilities has grown in popularity (Fischer et al., 2022). Nambisan and Baron (2013) explained that interactions between institutions (such as education or business development), stakeholders, and entrepreneurs themselves lead to entrepreneurial activity. It is possible to conclude that entrepreneurship exists as a practice that can help the local economy by utilizing the goods and services provided by entrepreneurial actors. The ecosystem has become a common setting for entrepreneurship and innovation. According to Shi and Shi (2022), the distribution of resources in an entrepreneurial ecosystem occurs like four interrelated themes: resource endowments, resource use, resource dynamics, and enabling conditions for resource dynamics.

Aliabadi et al. (2022) explore the indicators of a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem for agricultural startups, focusing on economic, environmental, social, and cultural factors. Using summative content analysis and the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process, it identifies and weights key dimensions of the ecosystem. Data from 25 experts were analyzed with MICMAC software, highlighting the importance of ecological, economic, and institutional dimensions. Cross-impact analysis revealed that employment, business ownership, income, legal reforms, information access, NGO presence, and risk awareness significantly impact sustainability. 12 key factors were selected, and the analysis indicated that the current ecosystem is unsustainable. On the other hand, there are six interrelated complex properties of a viable entrepreneurial ecosystem, according to Han et al. (2021): a large number of self-organized agents, non-linear interactions, sensitivity to initial conditions, adaptation to the environment, the emergence of successful entrepreneurial firms, and coevolution. On the other hand, essential implications for entrepreneurship progress could be summarized as follows (Mason & Brown, 2014). First, policies have to be dynamic because ecosystems are changing and continuously evolving (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). Second, every ecosystem needs different policies that suit its unique environment. The variety of cultures, banking systems, and educational systems are all factors affecting the policy approaches. Duplicating other ecosystems is an immature approach that would most likely fail (Hospers, 2006; Martin & Sunley, 2003). Third, “Policy implementation has to be holistic”(Mason & Brown, 2014). Initiatives have a higher chance of success if implemented in a synergic environment. Fourth, there should be a distinction between small business policies and entrepreneurship policies as they are two different concepts. Small business policy aims to increase the number of start-ups regardless of their growth and survival rates, which is a bad public policy as Shane (2009) described. Unfortunately, it is embedded in public policies (Nightingale & Coad, 2013). On the other hand, entrepreneurship policy focuses on supporting start-ups with high growth potential. Consequently, the participants, ventures, business models, supporting organizations, and cohesion around common ideals and activities vary across entrepreneurial ecosystems Roundy et al. (2017).

According to the Brown and Mawson (2019), the creation of entrepreneurial ecosystems has seen a surge in recent years, making it the newest "blockbuster" in industrial strategy. It proposes a fundamental typology of the various policy frameworks used under the cover of the ecosystem. The policy notion is primarily employed to encourage "more" entrepreneurship and is riddled with conceptual uncertainty. The idea has also been enthusiastically welcomed by regional policymakers, who have dubbed it the newest "blockbuster" in regional policy. Although research and practice have expanded quickly, the profundity of this policy bombshell cannot be guaranteed. On the other hand, to develop more knowledgeable policies to foster innovation and entrepreneurial opportunities, Feldman et al. (2022) suggested enhancing conceptualizations and measures of emergent ecosystems. Ferreira and Dabic (2022) concluded that entrepreneurial ecosystems significantly contribute to sustainable development and that entrepreneurial activities are a vital source of social and ecological sustainability. Even while we have made significant progress in our understanding of entrepreneurial ecosystems, we are still lacking in our ability to fully understand how localized events influence the transition to ecologically sustainable economic structures (Theodoraki et al., 2022). According to Kuebart (2021), open creative labs not only serve as valuable resources for startups and entrepreneurs, but they also serve systemic functions within entrepreneurial ecosystems. They specifically create conditions for critical links to form within regional entrepreneurial ecosystems and facilitate inter-ecosystem ties between regions.

Hitt et al. (2011), studied the integration of strategic entrepreneurship into key organizational sectors such as external networks and alliances, corporate resources and learning, innovation, and internationalization. Their research focused on both traditional theories (such as contingency theory and strategic fit) and novel theories (such as cultural entrepreneurship and business model drivers). In addition, the research integrates, expands, and tests theory and research from entrepreneurship and strategic management from resource-based perspectives, organizational learning, and institutional approaches. From an economic policy perspective, focusing too much on their development may be dangerous. Ecosystem research suggests that in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, every actor is of utmost importance for the ecosystem to function properly (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). Xin and Park (2024) investigate whether big businesses or institutions are more significant determinants of entrepreneurship. It examines how this relationship varies with economic development, impacts different types of entrepreneurships (opportunity vs. necessity), and identifies effective institutional factors. Analyzing data from 33 countries (2001–2015), the study finds a “N-shaped” relationship between big businesses and entrepreneurship. In high-income countries, big businesses positively influence opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Institutional factors such as supportive public policies and positive social perceptions are effective for opportunity-driven entrepreneurs but not for necessity-driven ones.

GovernmentGovernment is a major element of the policy perspective, and it covers institutions and regulations. This element is defined as the quality of government institutions, services, and regulations to guide and control the entrepreneurial activities within the state (North, 1990). Many scholars have studied the impact of entrepreneurship policy on economic growth (Acs & Szerb, 2007; Audretsch et al., 2002; Baumol et al., 2007; Gilbert et al., 2004). Research has implied that it is required to recognize the innovation policy needs. This innovation policy can be found in four different dimensions: innovation policy objectives, designs, implementations, and impacts (Vlačić et al., 2018). Innovation ecosystem development typically relies on formal and informal communication platforms designed to promote open discussion and collaborative activities. According to Gomes de Vasconcelos et al. (2018), value creation in innovation ecosystems has replaced value capture in traditional business settings. In the difficult macro environment, businesses are gradually realizing that engaging in innovation activities is crucial for gaining a competitive edge and generating value. By cooperating and competing to produce better goods and services, the participating players hope to jointly enhance their capacities (Russell & Smorodinskaya, 2018). According to Guerrero and Espinoza-Benavides (2021), entrepreneurship is a key factor in economic growth, increases economic competitiveness, and helps to create jobs. They found that governmental support for entrepreneurship favors re-entry after failure.

Government strategyGovernment strategy is a roadmap that guides the direction of the public and private sectors to achieve the vision of the state. The strategy objective is to optimize the organizational strength and to utilize its resources to gain the required results (Management Study Guide, 2021). Isenberg (2011) believes that “entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy represents a novel and cost-effective strategy for stimulating economic prosperity”. The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy is evolving to address some of the policy mistakes resulting from the way these strategies are conceived and executed.

Venture friendly legislationThis element is defined as the set of governmental regulations that control and rule ventures. Expediting the new value creation and demolishing the barriers can be achieved by the simplicity and effectiveness of these regulations (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021).

Research institutionsResearch institutions and centers are established for the purpose of conducting research. The outcome of these establishments should pour into the development of the entrepreneurship ecosystem. The return on investment is one of the indicators of the research institutions. (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021).

FinanceThis perspective is defined as the “presence of financial means to invest in activities that do not yet deliver financial means.” Financial support is an important factor for the growth of start-ups. It is beneficial for entrepreneurs to have accessibility to different kinds of funding such as venture capital funds, crowdfunding, angel investors, and loans (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). Start-ups (especially at their early stages) require financial support to thrive and expand. Private equity with all its types of funding is a major source of funding that can be found through channels such as venture capital and angel investors. Ecosystems with less maturity in private equity funding try to overcome that with governments’ initiatives. Governments provide capital to close the financial gaps and to enable entrepreneurs to survive and grow their business (Fuerlinger et al., 2015).

The rise of urban digital platforms has transformed entrepreneurial environments and boosted regional innovation. By analyzing data from 294 Chinese cities (2013–2020), the study found that digital platforms significantly enhance urban entrepreneurial activity. Key factors include reducing labor market distortions, improving the financial environment, and fostering technological innovation. Digital platforms have a greater impact in the eastern regions and cities with advanced industrial structures, with their effect increasing nonlinearly as platform development accelerates (Hu et al., 2024).

Venture capital fundsVenture capital is a kind of financial support provided by investors to small businesses with a potential of long-term growth (Chen, 2020). The public sector has been one of the active resources that support ecosystems, which started as a responsive act toward market failure (Brown & Mason, 2014). Venture capital sources have been focal points among the sources of the public sector (Colombo & Grilli, 2007; Cowling et al., 2009; Lerner, 2010). In the last two decades, business angel networks have been considered as agencies that enable entrepreneurs and investors to work together and find their ideal match (Brown & Mason, 2017).

Angel investorsAngel investors are individuals who invest their money in startups in exchange for equity. Angel investors tend to support the startups at their early stages. They group themselves into angel networks to share knowledge, information, and investment capital (McKaskill, 2009).

Public fundsThe governments’ financial support to entrepreneurs comes through grants, loans, or investments (Hayes, 2020; Stam & Van de Ven, 2021; Stam & Spigel, 2016). Governments provide public grants to startups with two major motivations: first, the belief that the startup's solutions would help achieve the government's goals. Second, the government realizes that other funding options are not mature and available yet. For example, supporting startups would result in creating more jobs, which is something the government could be working on and needs the cooperation from the private sector. The startups might be working on providing technological solutions that would help the overall digital transformation of the country (Startup Funding Book, 2021).

TaxationThe state of taxes includes items such as personal income taxes, capital gains taxes, and payroll taxes (Elert et al., 2019). According to Elert et al. (2019), the major suggested tax categories that are related to entrepreneurship are as follows: labor, corporate, dividend, capital gains, wealth, and stock options taxation.

Culture and supportThe perspective of culture can be defined as how the community within a region understands, admires, and reacts with entrepreneurship while the support aspect refers to business incubators, accelerators, universities, and conferences (Fritsch & Wyrwich, 2014; Stam & Van de Ven, 2021). The culture and positive societal norms are critical factors for the success of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Isenberg, 2011). Entrepreneurship ecosystems cannot grow in societies that do not value the entrepreneurs’ contributions and view failure negatively (Isenberg, 2010; Brown & Mason, 2017; Mason & Brown, 2014). Some ecosystems offer attractive environments for ambitious entrepreneurs and help in spreading ambition (Starr & Saxenian, 1995). Entrepreneurship culture has been measured in different forms (Credit et al., 2018). The prevalence of startups is one of the ways to measure culture. Another way is measuring how viable the career path of self-employed within the society. Moreover, measuring how successful entrepreneurs are appreciated (Stam & Van de Ven, 2021).

Societal normsSocietal norms are defined as the “Informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies” (Geertz, 1973). It has a noticeable influence on the entrepreneurs’ behaviors toward entrepreneurship. Therefore, it has an effect in the entire ecosystem (Kreuzer et al., 2018). People tend to fear the pressure of society and the risk of losing their prestige if they fail in their business. This social risk is greater than financial risk and the risk of losing time (Jammalamadaka & Bernstein, 1999). “Hence, there is a link between a society's stigma of failure and the amount of entrepreneurial activity within it” (Johansson, 2006). Countries with limited business failure tolerance such as many European countries are attached to bankruptcy. “Those who fail and go bankrupt tend to be considered as (losers) by their peers, and furthermore, it is a great challenge to obtaining financing for a new venture, since investors are reluctant to invest in (failed entrepreneurs) (Aho et al., 2006; EIT, 2012; European Commission, 1998, 2013) and tend to avoid risks overall” (Fuerlinger et al., 2015).

Incubators and acceleratorsIncubators are organizations that “assist emerging ventures by providing support services and assistance in developing their business” (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005). Incubators exist to link technology, capital, and the knowledge to empower talents and the growth of startups. Incubators provide a variety of services to support startups and enable entrepreneurs to grow in a competitive environment. Creating business plans, building teams, obtaining funds, providing workspaces, and other business services are all services offered by incubators. Incubators support entrepreneurs at their very early stages of creating business ideas until they make it ready for investment (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005). On the other hand, there are “accelerators” that have a more focused goal of expediting the growth of existing startups. Accelerators are organizations that support startups through coaching, funding, mentoring, and providing workspace (Clarysse et al., 2016; Miller & Bound, 2011).

UniversitiesTransferring the existing knowledge and developing new knowledge through research are the traditional roles of universities (Lombardi et al., 2021; Philpott et al., 2011). However, the entrepreneurial universities have an additional major role in the evolution of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Guerrero et al., 2014; Guerrero & Urbano, 2014). Universities are the main source of knowledge creation that supports the ecosystem growth (Cantner et al., 2021). Moreover, universities play an essential role in transferring knowledge (Colombelli et al., 2016; Mack & Mayer, 2016). Entrepreneurship and business departments have an important role in spreading awareness and entrepreneurial spirit within their universities (Egeln et al., 2010).

DigitalizationDigitalization is one of the newest change agents of the entrepreneurial ecosystems’ qualities. It is defined as the process of converting sets of analog information into digital bits (Brennen & Kreiss, 2016). The dynamics of business have been changing with digital transformation. European and American firms have started to recognize the business changes in China as a result of digitalization (Prud'homme et al., 2020). As digitalization increases, opportunities are being created and companies must be aware to leverage customer relationships and expand their sales (Weill, 2015). Autonomous digital processes, instant feedback, and accurate customers’ demands can all be obtained by digitalization (Dedehayir et al., 2018). Based on MIT Center of Information Systems Research, 32 % of companies’ revenue will be threatened by digital disruption (Weill, 2015). On the other hand, Chen et al. (2024) examine how digital transformation impacts knowledge creation in manufacturing enterprises using China-based panel data from 2007 to 2020, grounded in Nonaka's SECI model. Findings reveal that digital transformation positively influences all knowledge creation processes, with a notable impact on knowledge combination. However, digitalization has limited effects on externalization and combination, and it negatively affects socialization and internalization. The benefits of digital transformation are more pronounced in state-owned and large enterprises, and it enhances firms with strong existing knowledge creation capabilities. Regional digital technology levels and innovation culture also moderate these effects, contributing to a deeper understanding of digital transformation's role in knowledge creation.

Human capitalThe human capital perspective refers to the factors related to the ability of individuals to be entrepreneurs. It can be measured through individual skills, training, academic background, and business experience. Inspired by Becker (2009), Unger (2011) defines human capital as “the knowledge and skills acquired through schooling, on-the-job-training, and other types of experiences'' (Østergaard & Marinova, 2018, Ozpamuk et al., 2023). Isenberg's (2011) entrepreneurship ecosystem suggests studying the human capital perspective for five reasons: “it gives a holistic understanding; shifts the unit of analysis from firm towards the entirety of the actual ecosystem; it is linked to the ‘economic gardening’ approach in a specific environment; de-emphasizes the importance of firm-size, and emphasizes firm growth and the need for it to be actively fostered” (Isenberg, 2011; Mason & Brown, 2014; Østergaard & Marinova, 2018). The literature review shows how essential is the human factor to entrepreneurial success (Østergaard & Marinova, 2018).

Individual skillsThis element is defined as the set of individual business and leadership skills that enable entrepreneurs to succeed in starting a business. According to Isenberg (2011), the human capital factor can be explained as “labors: skilled and unskilled, serial entrepreneurs, and later generation families; and as educational institutions: general degrees (professional and academic) and specific entrepreneurial training” (Østergaard & Marinova, 2018). Suresh and Ramraj (2012) suggested that skilled individuals can boost entrepreneurial growth.

TrainingThe training factor can be explained as the available programs within the public and private sector that provide individuals with the set of business skills. Isenberg (2011) provides a group of intangible skills that can be obtained by training.

Academic backgroundThis factor refers to the higher level of educational background that individuals have when they start their business. Formal education enables individuals to develop their mindsets and gain the knowledge that helps them analyze the market and hunt opportunities. This education is valuable regardless if it was science-based or general business education, it builds learning attitudes, and opens new horizons for innovative projects (Grant, 1996; Shane, 2009; Bischoff et al., 2018; Fayolle et al., 2021). Meta-analysis shows that entrepreneurship performance is influenced by formal education (Van der Sluis et al., 2005). Thus, entrepreneurs with higher levels of education have a greater chance of surviving in business (Baptista et al., 2007).

Business backgroundBusiness background refers to the cumulative years of experiences and challenges that individuals passed through. The productivity of entrepreneurs can be improved by having work experience, leadership experience, and industry experience. Start-ups with greater human capital can comprehend the market faster and have less uncertainty. Having experience in a specific industry, and then launching a startup in the same industry optimize the experience usefulness (Baptista et al., 2007).

MarketThe literature defines market in its simplest form as the medium where two or more parties are engaged in an economic transaction (Kenton, 2021b). In previous research, the market perspective was illustrated by breaking it down to market size, entrepreneurial network, early adopters, distribution channels (Mason & Brown, 2014).

Market sizeMarket size is defined as the number of potential buyers in a specific market segment (Zhuo, 2017). Research shows that the desire to become an entrepreneur increases respectively with the increase in the population density, which means a larger market size. A 10 % increase in the population density results in a 1 % increase in the share of people who would like to become entrepreneurs (Sato et al., 2012). Sizing the market is an important early step for startups especially if the startup is seeking financing from VCs or angel investors. Investors are willing to invest in a large market with at least ($1 billion) (Estimating Market Size, 2009; Matsuyama, 1992).

Entrepreneurial networksThe entrepreneurial network refers to the relationships that are formed based on entrepreneurial activities (Chiesi, 2018). Donckels and Lambrecht (1995) defines entrepreneurial networks as “organized systems of relationships with customers, suppliers, and other entrepreneurs, with relatives, external consultants and other agents, or potential partners”. Many owners of startups earn their experiences, and develop networks from larger firms they were working at before running their own new business or during running the new business (Young et al., 1994). Granstrand and Holgersson (2020) described the innovation ecosystem as a dynamic group consisting of actors, activities, human components, related institutions, and linkages. An innovation ecosystem is the dynamic collection of participants, pursuits, and outputs. For an actor or a population of actors to perform in an innovative manner, the institutions, and relationships, including complementary and substitute relationships, are crucial. On the other hand, the relationship should be as simple, practical, and economical as feasible so that the associated transaction costs can be minimized, and the ecosystem's profitability is maximized (Möller & Halinen, 2017).

Early adoptersIndividuals or businesses who seek to obtain new products first in the market despite the high risk and cost are considered early adopters (Kenton, 2021a). Having knowledge about early adopters helps startups develop innovative solutions. By understanding this segment of the customers, startups would be able to better predict what kind of products are needed in the market (Reinhardt & Gurtner, 2015).

Distribution channelsA distribution channel is defined as “a chain of businesses or intermediaries through which a good or service passes until it reaches the final buyer or the end consumer. Distribution channels can include wholesalers, retailers, distributors, and even the Internet” (Fernando, 2021).

Methodology and resultsThis research developed a universal assessment model that can be adopted in different cities for implementing an effective entrepreneurial ecosystem. The research model is shown in Fig. 2. The research would start first with a literature review covering entrepreneurship and innovation metrics, entrepreneurial ecosystems, critical factors affecting the ecosystems, and the methodology. It would then move to evaluating the model and analyzing the results, followed by the experts’ contributions, and proposed future work.

Riyadh is chosen for this entrepreneurship research due to Riyadh aims to diversify the economy away from oil dependency by fostering entrepreneurial activities. As the capital city, Riyadh is at the heart of government initiatives designed to support startups, benefiting from a range of policies and programs that facilitate business growth. The city boasts a burgeoning entrepreneurial ecosystem, supported by numerous incubators, accelerators, and investors, which provides a dynamic environment for research. Additionally, significant investments in infrastructure and strategic locations further enhance Riyadh's attractiveness for studying entrepreneurship. Recent cultural and social changes, including increased female workforce participation and a shift toward new business models, contribute to a unique and evolving entrepreneurial landscape in Riyadh.

HDM is the proposed methodology to assess and evaluate entrepreneurial ecosystems. The structure of this methodology includes four different levels: objective, perspectives, criteria, and alternatives (El-Wahed & Al-Hindi, 1998). It was developed from the Analytic Hierarchical Process (AHP), which is a process that relies on pairwise comparisons conducted by a panel of experts. These comparisons are done between different criteria and sub-criteria of an alternative that would achieve the objective of the model (Saaty, 2008). AHP is a very well-known and widely used method that depends on multiple criteria (Vaidya & Kumar, 2006). This methodology covers subjective and objective measures that lead to presenting mechanisms that reduce the possible bias in decision making. For complex decisions, the main goal must be divided into criteria and sub-criteria. This allows decision makers to consider the different perspectives of any complex decision. Thomas L. Saaty created this method to be used as a practical practice for complex decisions. It is a simple but powerful tool, which motivates many decision makers and researchers to use (Forman & Gass, 2001).

Inspired by AHP, HDM was introduced by Kocaoglu in the early 1980s (Barham 2019; Hogaboam 2018; Kocaoglu 1983) “The HDM is one of the most distinct methods for subjective approaches to help decision makers quantify and incorporate quantitative and qualitative judgments into a complex problem” (Daim, 2016). The main concept of HDM is similar to AHP introduced earlier by Saaty (1977). However, its computational approach is the Constant-Sum calculations rather than the Eigenvectors (Barham, 2019). HDM suggests dividing decision criteria into multi-level hierarchy referred to as mission, objectives, goals, strategies, and actions.

HDM has been used previously in many technology management fields such as technology assessment, decision making, and strategic planning (Hogaboam 2018; Estep 2017; Gibson 2016; Phan 2013; Chen & Kocaoglu 2008; Tran & Daim 2008; Kocaoglu 1983). It is a powerful method that can generate quantitative data out of collecting experts’ subjective judgements. These quantitative data can then be analyzed effectively (Barham, 2019).

According to the HDM methodology developed by Kocaoglu (1983), pair-wise comparisons are made between each item in every layer of the model. After conducting the pair-wise comparisons, normalized matrices are generated with the expert judgments. The importance of every component of a given layer relative to the layer right above it is extracted by averaging the rows of the normalized matrices. The importance of every model component relative to the first layer (or the global importance) is calculated by multiplying its local importance (relative only to the layer above it) by the importance of its “parents” relative to the first layer. Bringing this rationale of using three layers to this study's model, the calculation of the factors’ importance relative to the mission, the Entrepreneurship Eco System, is given by the following equation:

Where:

Sn,jnENT = Relative value of the jnth factor under the nth perspective with respect to the ENT score.

PnENT = Relative priority of the nth perspective with respect to the ENT score, n = 1,2,3…N.

Fn,jnP = Relative contribution of the jnth factor under the nth perspective, jn = 1,2,3…N.

After having the importance of each factor relative to the mission, the determination of the Entrepreneurship Eco System score is given by multiplying the global importance of each factor by its desirability value, and making the total summation, as shown in the following equation:

Where:

Sn,jnENT = Relative value of the jnth factor under the nth perspective with respect to the ENT score.

Dn,jn= Desirability value of the performance measure corresponding to the jnth factor under the nth perspective.

For the desired research topic (Developing an Assessment Model for Entrepreneurship Ecosystems). It is important to select a methodology that can encompass all the perspectives of the ecosystem, a methodology that can simplify complex topics. Previously, HDM was selected because the structure of this methodology is similar to the entrepreneurial ecosystem model, where there are different domains (perspectives) and elements (criteria) within each domain. Moreover, experts implied that it is difficult to get the required data to conduct a quantitative research method and they have agreed that this method (HDM) would suit the purpose of this research.

We can evaluate HDM against several decision-making and assessment methodologies. Below is a comparison featuring HDM and six other methods:

Hierarchical Decision Model (Hdm)The Hierarchical Decision Model (HDM) is a decision-making framework that structures complex problems into a hierarchy of criteria and sub-criteria. It provides a clear structure for dealing with complex issues, facilitates multi-criteria decision-making, and can handle both qualitative and quantitative data. However, it can be complex to implement and requires expert input for accurate weighting. HDM is well-suited for evaluating complex, multi-faceted ecosystems that involve both qualitative and quantitative factors.

Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) uses pairwise comparisons and a hierarchical structure to prioritize and make decisions. It offers a structured approach, handles both qualitative and quantitative data, and uses pairwise comparisons to improve accuracy. However, it can be time-consuming, and subjective judgments might introduce bias. While AHP is similar to HDM, HDM may handle a larger number of criteria more effectively.

Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) evaluates multiple conflicting criteria, providing a comprehensive view of various criteria and being useful for complex decisions with trade-offs. It may involve complex computations and can be difficult to communicate results. Compared to general MCDA, HDM provides a clearer hierarchical structure, which can simplify the decision-making process.

Decision Matrix Method (DMM)The Decision Matrix Method (DMM) evaluates and prioritizes options based on weighted criteria. It is simple and easy to use, making it effective for straightforward decisions. However, it is limited to binary or nominal data and may not handle complex criteria well. HDM is better suited for complex evaluations with multiple layers of criteria, offering a more detailed approach than DMM.

Fuzzy LogicFuzzy Logic addresses uncertainty and imprecision using fuzzy set theory. It is effective for handling uncertainty and qualitative data but can be complex to implement and requires expertise in fuzzy logic. HDM integrates both fuzzy and crisp data, offering a structured approach to managing uncertainty, which complements fuzzy logic.

Delphi MethodThe Delphi Method is a forecasting technique that relies on a panel of experts to reach a consensus on future events. It benefits from expert-based consensus and is useful for forecasting and predicting. However, it can be subjective and potentially biased, and it is time-consuming. HDM complements the Delphi Method by structuring expert opinions into a hierarchical model, making decision-making clearer.

Integrated Value Model (IVM)The Integrated Value Model (IVM) integrates various value elements for decision-making, providing a holistic view and integrating diverse value elements. It can be complex and requires comprehensive data. HDM offers a more structured approach to integrating and prioritizing various criteria compared to IVM, providing a clearer framework for decision-making.

This HDM design was created based on literature review, previous independent studies, and published papers about entrepreneurial ecosystems. In addition to that, interviews with entrepreneurship experts helped to modify what was found in the literature review to build a practical model with high potential of successful implementations. This model includes five different perspectives as shown in Fig. 2 to assess the performance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. These perspectives are policy, finance, culture & support, human capital, and market. Four criteria are included under each perspective resulting in a total of twenty criteria. The policy perspective includes government, government strategy, venture friendly legislation, and research institutions. The finance perspective includes venture capital funds, angel investors, public funds, and taxation. The culture & support perspective includes societal norms, incubators & accelerators, universities, and digitalization. The human capital perspective includes individual skills, training, academic background, and business experience. The market perspective includes market size, entrepreneurial networks, early adopters, and distribution channels. Desirability curves for the criteria are presented in the appendix.

Based on the literature review, definitions of the perspectives of the entrepreneurial ecosystems were grouped in Table 1.

Perspectives of factors affecting entrepreneurial ecosystems.

| Perspectives | Details | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | The set of government guidelines, regulations, and services that control entrepreneurial activities. | (Management Study Guide), Brown and Mason (2017), Audretsch et al. (2015), Mason and Brown (2014), Stam and Van de Ven (2021), Vlačić et al. (2018) |

| Finance | The presence of financial means to invest in activities that do not yet deliver financial means. | Stam and Van de Ven (2021), Fuerlinger et al. (2015), Fuerlinger et al. (2015), Isenberg, (2011), Isenberg, (2010) |

| Culture & Support | Culture is defined as how the community within a region understands, admires, and reacts with entrepreneurship. While support refers to the variety of factors, organizations or entities that support the ecosystem such as incubators, universities, accelerators, and digitalization. | Fritsch and Wyrwich (2014), Stam and Van de Ven (2021); Brown and Mason (2017), Credit et al. (2018), Stam and Van de Ven, (2021), Lombardi et al. (2021), Philpott et al. (2011) |

| Human Capital | Refers to the factors related to the ability of individuals to be entrepreneurs. It can be measured through individual skills, training, academic background, and business experience. | Becker (2009), Unger et al. (2011), Østergaard and Marinova (2018) |

| Market | Market is any place where two or more parties can meet to engage in an economic transaction | Kenton (2021b) |

Based on the literature review, definitions of the criteria of the entrepreneurial ecosystems were grouped in Table 2.

Criteria of the perspectives affecting entrepreneurial ecosystems.

| Criteria | Details | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Policy Perspective | ||

| Government | The quality of government institutions and regulations to guide and control the entrepreneurial activities within the state. | North (1990), Stam and Van de Ven, (2021), Acs and Szerb (2007), Audretsch et al. (2002), Baumol et al. (2007), Gilbert et al. (2004) |

| Government Strategy | Government strategy is a roadmap that guides the direction of the public and private sectors to achieve the vision of the state. | (Management Study Guide); Isenberg (2011), (Management Study Guide) |

| Venture Friendly Legislation | The set of governmental regulations that control and rule the ventures. | Stam and Van de Ven, (2021). |

| Research Institutes | Research institutions and centers are established for the purpose of conducting research that pours into the development of the entrepreneurship ecosystem. | Stam and Van de Ven, (2021). |

| Finance Perspective | ||

| Venture Capital Funds | Financial support provided by investors to small businesses with a potential of long-term growth. | Chen (2020), Brown and Mason (2014), Colombo and Grilli (2007), Cowling et al. (2009), Lerner (2010), Brown and Mason (2017) |

| Angel Investors | Individuals who invest their money in startups in exchange for equity at the early stages. | McKaskill (2009) |

| Public Funds | The governments’ financial support to entrepreneurs through grants, loans, or investments. | Hayes (2020), Stam and Van de Ven, (2021), Stam and Spigel, (2016) |

| Taxation | The state of taxes such as personal income taxes, capital gains taxes and payroll taxes. | Elert et al. (2019) |

| Culture & Support Perspective | ||

| Societal Norms | Informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies. This includes attributes such as risk taking, self-efficacy, and proactiveness. | Geertz (1973), Kreuzer et al. (2018), Jammalamadaka and Bernstein (1999), Johansson (2006), Fuerlinger et al. (2015), Das and Teng (1997), Stewart and Roth (2004), Krueger and Dickson (1994) |

| Incubators & Accelerators | Incubators are organizations that assist emerging ventures by providing support services and assistance in developing their business.Accelerators are organizations that support startups through coaching, funding, mentoring, and providing workspace. | Grimaldi and Grandi (2005), Miller and Bound (2011), Clarysse et al. (2016), Becker and Gassmann (2006), Brown and Mason (2017) |

| Universities | Institutions that develop new knowledge through research and transfer the existing knowledge. | Colombo and Grilli (2007), Lombardi et al. (2021), Colombelli et al. (2016), Mack and Mayer (2016), Philpott et al. (2011) |

| Digitalization | Simplifying an existing working process and increasing its efficiency by converting analog information into digital. | Brennen and Kreiss (2016), Prud'homme et al. (2020), Weill (2015), Dedehayir et al. (2018) |

| Human Capital Perspective | ||

| Individual Skills | The set of individual business and leadership skills that enable entrepreneurs to succeed in starting a business. | Isenberg, (2011), Østergaard and Marinova (2018), Suresh and Ramraj (2012) |

| Training | Available programs within the public and private sector that provide individuals with a set of business skills. | Isenberg (2011), Østergaard and Marinova (2018) |

| Academic Background | The higher level of educational background that individuals have when they start their business. | Shane (2009), Grant (1996), Van der Sluis et al. (2005), Baptista et al. (2007) |

| Business Background | The cumulative years of experiences and challenges individuals have passed through. | Baptista et al. (2007). |

| Market Perspectives | ||

| Market Size | The number of potential buyers in a specific market segment. | Zhuo (2017) |

| Entrepreneurial Network | The relationships that are formed based on entrepreneurial activities. | Chiesi (2018) |

| Early Adopters | Individuals or businesses who seek to obtain new products first in the market despite the high risk and cost. | Kenton (2021a) |

| Distribution Channels | A chain of businesses or intermediaries through which a good or service passes until it reaches the final buyer or the end consumer. Distribution channels can include wholesalers, retailers, distributors, and even the Internet. | Fernando (2021) |

Our research included fourteen expert panels as shown in Table 3.

Research expert panels.

| Panel | Mission | Tool |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Validate the perspectives | * |

| P2 | Validate the criteria under the policy perspective | * |

| P3 | Validate the criteria under the finance perspective | * |

| P4 | Validate the criteria under the culture & support perspective | * |

| P5 | Validate the criteria under the human capital perspective | * |

| P6 | Validate the criteria under the market perspective | * |

| P7 | Quantify the perspective | ** |

| P8 | Quantify the criteria under the policy perspective | ** |

| P9 | Quantify the criteria under the finance perspective | ** |

| P10 | Quantify the criteria under the culture & support perspective | ** |

| P11 | Quantify the criteria under the human capital perspective | ** |

| P12 | Quantify the criteria under the market perspective | ** |

| P13 | Validate and quantify desirability curves | *** |

| P14 | Assess Riyadh city's entrepreneurial ecosystem using desirability curves | *** |

* Qualtrics Survey, ** ETM HDM software, *** Interviews.

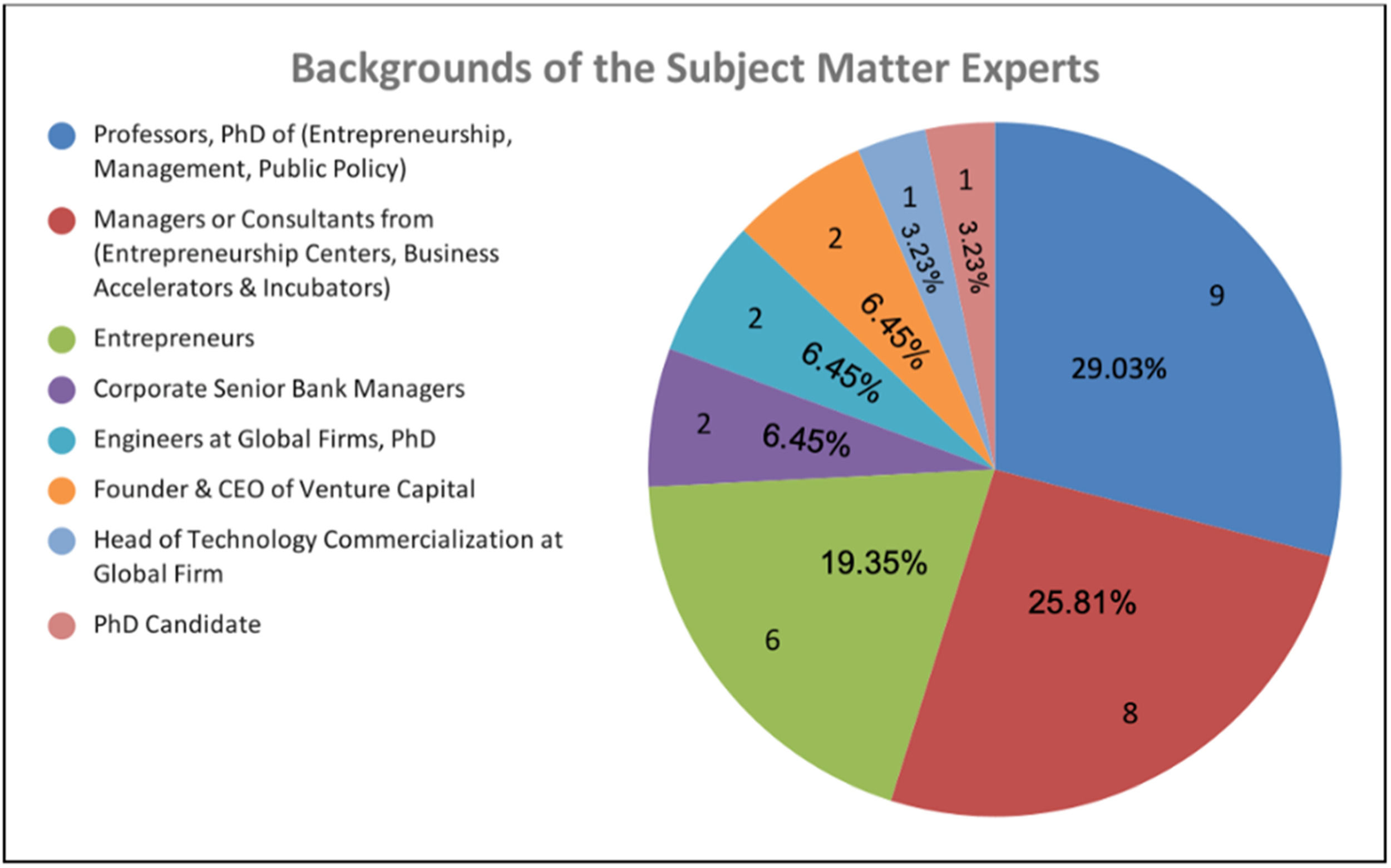

The subject matter experts’ list was created based on two approaches: 1- Bibliometric Social Network Analysis (SNA); 2- Networking and identifying potential organizations and authors based on literature review and snowball sampling. Fig. 3 shows the visualization of the subject matter experts’ backgrounds:

The HDM model was developed based on literature review and then modified based on experts’ interviews. After that, a survey was sent to expert panels to validate the model's perspectives and criteria. These panels included a total of 31 experts who were identified after conducting social networks analysis (SNA), literature review and networking. Invitations emails to join the expert panels were sent to all the experts with a brief background about my research topic. This was followed by another email with the validation survey link and the specific objective of this survey. The objective of this survey was to validate the identified factors that affect building entrepreneurial ecosystems. This survey intended to capture experts’ judgments of the suitability of these factors or identify any missing factors. In this survey, experts were asked (Yes / No) questions to confirm that the considered perspective or the proposed criteria are related to measuring the performances of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Experts were given the chance to suggest other factors in each question if they believe a critical factor needs to be included. Definitions of all the perspectives and criteria were included to assure the clarity of what each perspective and criteria refers to. The minimum acceptable percentage of each perspective and criteria was set to be at least 67 % in order to be validated (Phan, 2013). The perspectives and criteria received validation between 96 % and 71 %.

The final model weights were calculated as explained earlier in the methodology section by multiplying the local criterion weight by its perspective weight (Fig. 4).

The final weights of these perspectives were close to each other. Market and human capital were at the top followed by finance, culture and support, and policy respectively with similar weights. The market perspective was found to be the most important perspective with a weight of (26.2 %), followed directly with the human capital perspective that is equal to (25.2 %). The finance perspective was the third most important one with a weight of (17.9 %), followed by the culture and support perspective with a weight of (16.2 %) in fourth place. The least important perspective was found to be policy with a weight of (14.4 %). These findings of ranking market and human capital as the top two perspectives align with the feedback from some experts’ interviews. Experts believe that successful entrepreneurs will thrive despite the regulations’ challenges, and hence they are considered the most important factor in the ecosystem. Startups with great teams would succeed in a large addressable market despite the difficulty of financing. Entrepreneurs with limited financing but operating in a large market would have a better chance of scaling and growing than entrepreneurs with strong financing in a smaller market.

Narrowing the discussion to the criteria level, the most important criterion in the whole model was found to be market size with 8.5 %. The second most important criterion was found to be training with 7.1 %. The third most important criterion was found to be individual skills with 6.9 %. The fourth most important criterion was found to be entrepreneurial network with 6.7 %. The fifth most important criterion was found to be business background with 6.6 %.

Sensitivity / scenario analysisScenario analysis is one of the sensitivity analyses approaches to test the flexibility of HDM models toward changes. The model can be misleading if the perspectives or criteria get impacted by time. If a factor with high sensitivity gets changed, then the pairwise comparison needs to be reconducted (Gibson, 2016). For this research, five extreme scenarios are implemented. The results show positive and negative changes but not remarkably high except for scenario four and five. Scenario four (human capital emphasis) has decreased the final score of Riyadh from 69.7 (original score) down to 51.4, which is a difference of (−18.4) points. This is because the human capital's criteria of Riyadh were evaluated as low in general. Thus, assuming that human capital is the most important perspective decreased the overall score of Riyadh. However, Al Khobar's final score decreased with only (−5.9) within this same scenario. A similar case was seen in scenario five (market emphasis), where the new score of Riyadh was calculated to be 87.9 (18.2 higher than original score). Except in this case, it is a positive change. This is because Riyadh has received a high evaluation of the market's criteria and boosting this perspective has increased its overall score. On the other hand, Al Khobar's final score has increased by (13.5) points. This means that there should be more preparations if scenario four or five applies considering that both had the highest changes. Finally, the scenario analysis shows that there are changes but they are not significant in most of the scenarios. This is by applying extreme scenarios, which in reality will be less extreme. Thus, the model can be considered dependable enough.

Case study applicationThe entrepreneurial ecosystem of Riyadh cityRiyadh city is the capital of Saudi Arabia with a current population of 7.5 million. It is located in Riyadh province, which is one of 13 provinces in the kingdom. Riyadh is the most important financial and business city in Saudi Arabia (Kim, 2021).

It is important to provide a brief overview about Saudi Arabia's entrepreneurship status as a whole before narrowing it down to the city of Riyadh. The country has experienced noticeable growth in the past five years that was boosted by government initiatives and foreign investments (Alwazir, 2020). The Saudi vision of 2030 has been a great entrepreneurship enabler with its initiatives, programs, and policies. The governor of the Saudi SME Authority (Monsha'at), Mr. Saleh Alrasheed stated that the goal is “to make Riyadh a world-class ecosystem for startups and investors by the collective efforts of many stakeholders” (Genome, 2020). Overall, entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia has evolved rapidly over the past few years. The Saudi government has an objective of creating a healthy ecosystem of entrepreneurs. This includes creating positive culture, providing access for funding, formulating venture friendly legislations, and creating enabling policies. All these improvements can be done with the support from stakeholders such as the big corporations, universities, risk capitals, and entrepreneurs. The current focus is to increase the technology based and innovative startups as it is part of the new shape of economies that relies on data and technology (Proven Marketing Team, 2020).

The Global Startup Ecosystem Report (GSER) 2020 has shown that the ecosystem value was $1 bn, while the global average was $10.5 bn. The total early-stage funding was $142 million, while the global average was $431 million (Genome, 2020).

Riyadh city includes several national banks, and most of the local and international companies. About 33 % of the factories in Saudi are in Riyadh. Simply, most of the business and career opportunities are in Riyadh with the largest market size in the kingdom (Kim, 2021). In 2019, four big projects with a cost of $23 bn were launched. These four projects are: King Salman Park, Sports Boulevard, Green Riyadh, and Riyadh Art. These projects are offering opportunities worth $15 bn for the private sector (Bridge, 2021). The capital city was listed within the top 40 economies in the world. However, the ambitious new goal revealed by the Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman during the Future Investment Initiative (FII) that was held earlier in 2021 at Riyadh is to be within the top 10 economies (Faeq, 2021).

The Saudi leadership believes in the concept that the world economies are not based on nations but on cities. This belief can be seen translated into actions taken toward boosting the economy of Riyadh. The vision of 2030 includes the goal of increasing the population from 7.5 million into 15–20 million residents by 2030 (Bridge, 2021). Riyadh generates about 50 % of the Saudi non-oil revenue. The cost of creating jobs is 30 % less than in the rest of the country's cities. Moreover, the cost of developing infrastructure and real estate is 29 % less than the other cities within the kingdom (Kane, 2021).

Among all the current efforts of developing the entrepreneurship ecosystem in Riyadh, there is a need for a scientific and practical approach to assess the performance of the city's entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Assessing the status of entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities is important for governments, policy makers, entrepreneurs, investors, and other stakeholders. It is a vital and critical process, but it is mostly beneficial when the assessments’ results are being used to detect areas of improvements. Practical actions can be then applied to increase the overall performance of the ecosystem by referring to the desirability curves metrics. The desirability curves describe the status of the next level an ecosystem must be at. Table 4 includes the details of the recommended actions to improve each criterion with the desired (improved VC value) and the (improved score).

Case study results.

| Case Study of Riyadh City | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perspectives | Criteria | Global Weight | VC Value | Score | Improved VC Value | Improved Score | Improvement Actions |

| Policy(14.4 %) | Government | 2.5 % | 80 | 2.0 | 80 | 2.0 | No action needed. |

| Government Strategy | 2.9 % | 75 | 2.2 | 75 | 2.2 | No action needed. | |

| Venture Friendly Legislation | 5.0 % | 70 | 3.5 | 70 | 3.5 | No action needed. | |

| Research Institutes | 4.0 % | 55 | 2.2 | 80 | 3.2 | Establishing new research institutes by the public and private sectors and supporting the existing institutes with more financial resources. Moreover, increasing the awareness about the importance of research in developing the ecosystem. | |

| Finance(17.9 %) | Venture Capital Funds | 4.6 % | 80 | 3.7 | 80 | 3.7 | No action needed. |

| Angel Investors | 5.2 % | 80 | 4.1 | 80 | 4.1 | No action needed. | |

| Public Funds | 3.8 % | 80 | 3.0 | 80 | 3.0 | No action needed. | |

| Taxation | 4.3 % | 20 | 0.9 | 55 | 2.4 | Reviewing the current taxation system and ensuring that it is supportive or at least not creating obstacles for starting or growing business. | |

| Culture & Support(16.2 %) | Societal Norms | 4.3 % | 80 | 3.4 | 80 | 3.4 | No action needed. |

| Incubators & Accelerators | 4.2 % | 85 | 3.6 | 85 | 3.6 | No action needed. | |

| Universities | 3.8 % | 50 | 1.9 | 85 | 3.2 | Enhancing the role of existing universities in supporting and educating the community about entrepreneurship. And increasing the engagement of the university within the community. | |

| Digitalization | 3.8 % | 85 | 3.2 | 85 | 3.2 | No action needed. | |

| Human Capital(25.2 %) | Individual Skills | 6.9 % | 80 | 5.5 | 80 | 5.5 | No action needed. |

| Training | 7.1 % | 50 | 3.5 | 85 | 6.0 | No action needed. | |

| Academic Background | 4.6 % | 50 | 2.3 | 80 | 3.7 | Encouraging more entrepreneurs with college degrees to start their own startups and utilize their academic background. This can be done through universities programs or raising the public awareness. | |

| Business Background | 6.6 % | 20 | 1.3 | 50 | 3.3 | Encouraging individuals to participate in business activities and build their business experience through working with existing firms or being part of family or other kind of business before launching their startups. | |

| Market(26.2 %) | Market Size | 8.5 % | 85 | 7.2 | 85 | 7.2 | No action needed. |

| Entrepreneurial Network | 6.7 % | 100 | 6.7 | 100 | 6.7 | No action needed. | |

| Early Adopters | 5.3 % | 85 | 4.5 | 85 | 4.5 | No action needed. | |

| Distribution Channels | 5.6 % | 85 | 4.8 | 85 | 4.8 | No action needed. | |

| Total | 100 % | 69.7 | 79.4 | ||||

For the case of Riyadh entrepreneurship ecosystem, there are five identified areas that require attention to improve. First, the research institutes under the policy perspective need to be improved from a VC of 55 to 80. This means improving research institutes from an average to a good level of contribution to the ecosystem as described in the value curve of this criterion.

Second, the taxation under finance perspective needs to be improved from a VC of 20 to 55. This means improving taxation from a taxation system that is at a low level and requires massive improvements to a taxation system that needs some improvements as described in the value curve of this criterion.

Third, the universities in culture and support perspective needs to be improved from a VC of 50 to 85. This means improving universities' status from a moderate number of universities that provide support and education to entrepreneurs into a good number of universities as described in the value curve of this criterion.

Fourth, the academic background under the human capital perspective needs to be improved from a VC of 50 to 80. This means improving the academic background of entrepreneurs from moderate level into a good level as described in the value curve of this criterion.

Fifth, the business background from the human capital perspective needs to be improved from a VC of 20 to 50 based. This means improving the business background of entrepreneurs from limited business backgrounds when they start their startups into a moderate business background as described in the value curve of this criterion.

DiscussionMarket perspective was found to be the most important factor of entrepreneurial ecosystems with a relative weight of (26.2 %). Market in the context of this research was simply defined as the medium where two or more parties engage in an economic transaction (Kenton, 2021b). As the definition of market implies, entrepreneurial activities occur in the market “medium.” This makes it a reasonable finding as it is the element that encompasses all of the business and entrepreneurship activities. Assuming an ecosystem at city X recruited the best entrepreneurs with unlimited funding and were provided all the support from government and the society, these entrepreneurs will not be able to launch successful startups without the presence of market. There is nothing entrepreneurs can do regarding the absence of a market or having a small market except for some kind of business models that are fully virtual. The major finding implies that the market is a vital factor to entrepreneurial ecosystems. The four criteria under the market perspective were evaluated separately and were given a combined total of 100 % divided between the four criteria. Then, a global weight was calculated as explained previously in the methodology section. The same scenario applies to the rest of the other perspectives. The market size criterion (Zhou, 2017) was found to be the most important criterion with a relative local weight of (32.5 %). This makes it the most important criterion in the entire model with a global relative weight of (8.5 %). This research finding aligns with the literature review and the experts’ opinions. Research shows that the desire to become an entrepreneur increases respectively with the increase in the population density, which means a larger market size. A 10 % increase in the population density results in a 1 % increase in the share of people who would like to become entrepreneurs (Sato et al., 2012). Estimating the market size is a necessary step at the stage of formulating the business plan or if the startup is looking for financing from venture capital. Large market with at least ($1 billion) is what attracts investors (Estimating Market Size, 2009; Matsuyama, 1992). The entrepreneurial network criterion (Chiesi, 2018) was ranked second with a relative local weight of (25.6 %). Moreover, it was ranked fourth within the entire model with a global weight of (6.7 %). Some literature highlighted the benefit of shared entrepreneurship knowledge within the community, but there was not much emphasis on its influence in the ecosystem (Fischer & Reuber, 2003). The distribution channels (Fernando, 2021) criterion was placed third with a local weight of (21.5 %). The least important criterion was found to be the early adopters with a relative local weight of (20.4 %).