As the expenses associated with new product development (NPD) continue to rise, intellectual capital (IC) plays a critical yet understudied role in influencing NPD performance (NPDP). To address this, we present a comprehensive theoretical framework to empirically analyze how IC provides pharmaceutical companies with essential capabilities to enhance NPDP through the perspective of organizational learning (OL). This study employs a multi-source, time-lagged, and survey-based approach to gather relevant data from pharmaceutical companies. The findings reveal positive relationships between IC components—human, structural, and relational capital— and OL. Moreover, OL emerges as a pivotal predictor of the link between IC components and NPDP. Notably, we uncover that the association between OL and NPDP is moderated by the presence of an innovation culture within organizations. This research significantly contributes to the existing literature by providing new empirical insights into the strategic role of IC in promoting the creation and dissemination of new knowledge within organizations. These insights have substantial implications for practitioners and academics by bolstering firms' capacity for NPDP in knowledge-based sectors.

In today's rapidly evolving business emvirinment, an organization's capacity for innovation is fundamental to sustaining and enhancing its competitive edge. Companies are increasingly urged to become knowledge-based and rely more on intangible assets to drive innovation (Moghaddam et al., 2015; Pak et al., 2023). Intellectual capital (IC), which encompasses these valuable and inimitable intangible resources, plays a pivotal role in facilitating innovation success (e.g., Farzaneh et al., 2022) by either sourcing crucial information externally or leveraging accumulated internal knowledge (Mehralian et al., 2023). To thrive in complex business environments and generate value, knowledge-based firms increasingly rely on IC for strategic knowledge management (Rehman et al., 2021; 2022). Numerous studies have linked IC to firm performance through absorptive capacity (Oliveira et al., 2020), dynamic capabilities (DCs) (Hsu & Wang, 2010; Mahmood et al., 2017), knowledge management practices (Obeidat et al., 2017), and innovation capability (Inkinen, 2015). Other research emphasizes human capital efficiency (Makki & Lodhi, 2008) and entrepreneurship (Asiaei et al., 2020) in the IC-financial performance relationship. Despite these research efforts, the precise mechanisms by which IC influences innovation performance remain underexplored, warranting further investigation (Mahmood et al., 2017).

On the other hand, some researchers argue that new product development performance- (NPDP) is a significant indicator of a firm's innovation achievements and is essential for sustained performance (Subramanian & Vrande, 2019). However, the relationship between IC and NPDP is poorly understood and remains a topic of debate, thus necessitating further theoretical and empirical examination. This study employs an organizational learning (OL) perspective to understand how facets of IC enhance NPDP in organizations. The central premise is that the efficacy of a firm's IC as a foundation for NPDP should be evaluated in tandem with the knowledge learned from external or internal sources (You et al., 2021). OL enables knowledge acquired externally to be shared and integrated in the firm to create innovative products, technologies, and services (Li et al., 2019). In organizations with robust IC, OL empowers them to identify market opportunities and meet customer needs more effectively by facilitating collaborative actions under varying conditions to foster innovation (Farzaneh et al., 2022). Research that combines IC and OL has yielded valuable insights into the IC-performance relationship (e.g., Cabrilo & Dahms, 2020; Han & Li, 2015). However, this study offers new perspectives. It considers NPDP the dependent variable and IC a construct encompassing three distinct components: human, structural, and relational capital. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following research question: how can firms enhance NPDP by aligning IC and OL?

While the extensive literature on IC acknowledges its importance for NPDP, previous studies have generally overlooked how innovation culture might influence the IC-NPDP relationship. This topic warrants attention, as NPDP requires a culture that fosters creativity, tolerates risks, and promotes personal growth (Farzaneh et al., 2022). An innovation culture boosts employee commitment, motivation, and knowledge, yielding improved product innovation outcomes (Castro et al., 2013). Innovation culture encourages employees to share knowledge with colleagues and cultivates a shared belief that emphasizes acquiring, sharing, and applying knowledge (Alattas et al., 2016). Although previous research has emphasized the influence of culture on OL (Pellegrini et al., 2020; Flores et al., 2012), this study specifically examines the role of innovation culture as a contextual factor in analyzing the IC-NPDP relationship. Innovation culture fosters openness to new ideas and enhances internal capabilities to introduce novel concepts, processes, or products effectively. A culture encouraging employees to explore innovative opportunities and acquire new knowledge (Chen et al., 2014) motivates them to transform this knowledge into innovative products (Brettel & Cleven, 2011). However, a weak innovation culture can diminish its impact on NPDP even with robust IC.

This study aims to offer new insights into the factors driving corporate NPDP. First, it contributes to the ongoing debate by viewing IC as a concept comprising three distinct components, unlike earlier studies that treated it as a single entity (Han & Li, 2015). Second, this research assesses non-financial performance to explain how IC affects organizational performance, focusing on NPDP. Third, we add to the literature by discussing that innovation culture is a moderating factor explaining how OL can enhance NPDP in organizations with a strong innovation culture. Finally, the pharmaceutical industry was chosen as the sample for this research because it provides a highly innovative and research-intensive context for NPDP studies (Mehralian et al., 2018; Birkinshaw et al., 2016). The industry also heavily relies on knowledge assets for innovation (Bhatti et al., 2021). Therefore, pharmaceutical companies need to expand their IC to adapt to the ever-changing environment (Droppert & Bennett, 2015; Festa et al., 2020), making the sector an appealing context for research on IC and NPDP.

Theoretical background and hypotheses developmentIC is one of the organization's most pivotal intangible resources, developing over time and generating the knowledge necessary to function and thrive competitively (Paoloni et al., 2020). IC is the collective sum of a firm's knowledge, information, intellectual property, and experience used to gain competitive advantage (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019; Li et al., 2019). IC comprises three main components: human capital, referring to the workforce's knowledge, skills, experiences, and motivation; structural capital, encompassing institutionalized knowledge accrued through structures, organizational culture, and information systems; and relational capital, involving the embedded knowledge in business relationships and networks (Li et al., 2019; Pradana et al., 2020).

This study builds on the resource-based view (RBV) theory, recognizing that IC development within organizations can help firms obtain valuable and innovative market knowledge, identify opportunities, accumulate it, and translate it into inimitable insights. The RBV asserts that a firm's competitive advantage relies heavily on harnessing intangible resources. Since it is not well established to what extent IC aids organizations in leveraging learning to enhance NPD performance, this research aims to address this gap by creating and testing a conceptual model grounded in the RBV framework. When applied to performance, RBV implies that if IC is managed appropriately and utilized efficiently, these resources become valuable, unique, and irreplaceable, enabling firms to achieve competitive advantages (Barney, 1991; Rehman, 2022; Wernerfelt, 1984). Thus, effectively synthesizing and leveraging these resources is crucial to unlocking their potential.

This theoretical perspective offers a dynamic and innovative approach to elucidate the mechanism by which IC translates opportunities into superior performance, especially in NPDP. It serves as a basis for understanding how different IC components affect NPDP in firms.

IC and OLOrganizations equipped with knowledge workers possess the capability to learn from best practices and experiences and can acquire, distribute, and interpret knowledge efficiently (Ghasemzadeh et al., 2019). Research indicates that the relationship between IC and OL is crucial because it enables employees to absorb and disseminate knowledge throughout the organization, enhancing overall performance (Farzaneh et al., 2022). Previous studies have convincingly argued that firms can enhance and cultivate knowledge resources rooted in human, social, and organizational capital to improve performance (Youndt & Snell, 2004). However, the mechanism by which IC components drive NPDP remains underexplored.

To gain a deeper understanding, it can be inferred that learning is more effective when supported by robust human capital. The more skilled and knowledgeable the workforce, the better an organization can exchange, integrate, and absorb new knowledge and insights (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019). Companies need employees with broad skills and adaptability who can search for, assimilate, and recombine knowledge across various domains (Cabrilo & Dahms, 2020). Skilled, knowledgeable, and motivated personnel remain dedicated to acquiring more knowledge, learning, and self-improvement, thereby contributing to OL (Ramli & Rasdi, 2021). They generate the internal conditions necessary to promote and facilitate learning by doing (practice-based and experiential learning) as well as social learning (e.g., mentoring, coaching, job-shadowing) within the organization (Cabrilo & Dahms, 2020).

Nevertheless, some previous studies have yielded various results regarding the role of human capital in OL. For instance, Sun et al. (2020) also found that learning capabilities of R&D firms is at highest level when their human capital is low. In line with Ngah and Ibrahim (2011), human capital does not significantly impact knowledge sharing, a dimension of OL, in SMEs. Other studies have focused solely on human capital's impact on knowledge creation capability (Smith et al., 2005), overlooking other dimensions of OL, such as knowledge diffusion and organizational memory.

Conversely, another line of research empirically supports human capital as a significant driver of OL in companies. Taking a close look at how human capital affects organizational learning, findings from previous studies have shown that capacity, knowledge, and skills significantly contribute to firms' evolving innovation activities and ability to learn from failure (Tzabbar et al., 2023). Al-Husseini (2023) highlighted that substantial human capital enables employees to not only acquire new knowledge but also improve their skills, which opens the opportunity to develop learning capability. A similar relationship has been observed with respect to Mubarik et al. (2021), who proposed that a higher level of human capital enhances employees' ability to maintain strong connections with partners and absorb knowledge from them for learning. Dong et al. (2023) posited that improving OL entails that firms maintain an appropriate learning rate based on their human capital.

Regarding the impact of human capital on OL in knowledge-based companies, Li et al. (2019) found a positive influence of IC on knowledge sharing in Chinese construction firms. Other studies provided empirical evidence that employees' values, attitudes, and capabilities facilitate exchanging and integrating existing information, knowledge, and ideas. For instance, researchers such as You et al. (2021) demonstrated that OL shapes the relationship between human capital and innovation in Chinese township organizations.

Synthesizing empirical evidence, the philosophy underpinning the role of human capital in OL emphasizes that the expertise and experience embedded in human capital provide firms with a significant capacity to distribute knowledge, translate it into practical forms, and enrich organizational memory for the future (Farzaneh et al., 2018). Overall, human capital allows organizations to enhance OL and create positive feedback loops encouraging learning and development. Therefore, organizations with well-developed human capital can substantially improve their learning capabilities. Despite studies highlighting the importance of human capital in firms, further exploration of the specific link between human capital and OL is still needed. Given that human capital could be a crucial factor in enhancing OL, the hypothesis is as follows:

H1a:Human capital positively affects OL.

Given companies' resource limitations, they can leverage their relational capital for knowledge acquisition by establishing relationship-specific assets (Liu et al., 2010). The greater the relational capital within a firm, the more likely employees trust each other and form reciprocal relationships (Xin et al., 2020), thereby increasing the likelihood of acquiring external knowledge from partners. Substantial relational capital encourages employees to interact with various stakeholders to adopt new knowledge (Liu et al., 2010).

While relational capital can pave the way to facilitate learning, some studies argue that it does not establish strong knowledge networks (Durrah et al., 2018). Others went further and highlighted that relational attributes within a specific group cannot be expanded among organizational members through shared values, visions, and objectives in the learning process (Nam et al., 2023). Noteworthy, although these researchers underestimate the relational capital's role in knowledge acquisition, sharing, and interpretation, recent research has shown that inter-organizational relationships create opportunities for companies to acquire external knowledge and combine it with existing resources to enhance innovation performance (Li et al., 2019). For instance, Buenechea-Elberdin et al. (2018) proved that relational capital represents knowledge resources generated when tacit knowledge is shared inside and outside organizations. They found that relationships with customers, business partners, and research institutions foster a firm's learning ability by facilitating information and knowledge sharing as well as acquiring new knowledge. Another study found that employees with higher relational capital have a more extensive knowledge pool, leading to denser networks and more learning opportunities (Sharma et al., 2023).

To elaborate further, relational capital plays a dual role: connecting external networks and establishing trust and norms within the organization. This dual role helps organizations acquire critical knowledge resources for future development and facilitates employee's collaboration and learning (Jingbo, 2019). In this regard, Al-Husseini (2023) emphasized that the increasing of social interaction and mutual trust among members will help them to boost their skills and problem-solving abilities and motivate them to seek new knowledge, which in turn enhances the learning capabilities. Rehman et al. (2023) similarly emphasized that relational capital is crucial for interorganizational learning because of its ability to reinforce organizations to absorb knowledge, adequate routine to analyze knowledge, integrate existing knowledge with new knowledge, and learn new things from their partners. In similar vein, Sumanarathna et al. (2020) found that network ties, trust, and shared goals positively impact exploratory and exploitative learning through providing collaborative environments. In summary, relational capital primarily concerns with the knowledge that customers, suppliers, and other partners provide. The findings from those studies evidently demonstrate that higher relational capital fosters a learning climate, enabling organizations to learn from diverse stakeholders. This highlights the importance of tracking external knowledge accurately and effectively to become a learning-oriented organization. Thus, by comparing these two lines of research, the following proposal is made:

H1b:Relational capital positively affects OL.

Structural capital helps systematically document and retain knowledge within an organization's systems, processes, routines, and norms (Asiaei et al., 2020). It forms the basis of knowledge development practices across the organization, providing a greater opportunity to benefit from systematic collection and accumulation of knowledge for future use. When a firm establishes a database for sharing and saving employees knowledge, employees are often more willing to acquire, share, and request information (Al-Husseini, 2023). In this light, it is reasonable to posit that since structural capital pertains to a business's procedures, technologies, and patents, it can support the infrastructure needed for knowledge generation and improved performance (Schislyaeva et al., 2022). Organizations with robust structural capital typically foster a culture that encourages individuals to experiment, fail, and learn (Attar et al., 2018).

Despite the potential of structural capital to enhance OL, some studies have reported conflicting findings. For instance, Yusoff et al. (2019) found no positive correlation between structural capital and OL capabilities in their study of Malaysian manufacturing SMEs. Durrah et al. (2018) conducted a case study at a hospital in Paris and found no evidence of a relationship between structural capital and learning. Ahmadi et al. (2012) also observed a significant negative link between structural capital and learning capability. However, according to RBV, high institutionalized knowledge can facilitate smooth knowledge flow among employees, accelerating knowledge acquisition, internalization, and articulation. Accordingly, institutionalized knowledge empowers firms to reinforce existing knowledge and fosters the creation of learning capabilities.

In this line of reasoning, Li et al. (2019) found that enterprises primarily develop structural capital from organizational structures, practices, information systems, and manuals. Codified knowledge and systematic experience help firms apply their existing knowledge and experiences, integrate their prior knowledge, and accumulate experiences to address current challenges. Moreover, Chaudhary et al. (2023) systematically reviewed empirical studies on IC and knowledge-based capabilities, finding that structural capital positively influences OL. López-Zapata and Ramírez-Gómez (2023) confirmed the impact of structural capital on exploration and exploitation as two forms of OL. They further argued that structural capital integrates knowledge about the organization's current infrastructure, facilitates the use of existing capabilities, and introduces new ones by articulating knowledge systems and databases. Similarly, Ramli and Rasdi (2021) posited that organizations with solid structural capital have a culture that supports trying, failing, learning, and retrying. Their argument supported by other studies such as Kanten et al. (2015) that noted that both organic and mechanical structures significantly affected the learning organization. In light of this debate, the hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H1c:Structural capital positively affects OL.

OL and NPDPOL has become a foundational element of NPD. As a dynamic process, OL enables firms to discern market trends, absorb technological knowledge, incorporate that knowledge into their processes, and apply it to generate or introduce new products (Zhang et al., 2019). Such processes enhance the ability of firms to continuously develop new products and services to meet customers' needs and pave the way for firms to outperform their competitors (Li et al., 2019). Learning through hands-on experimentation, mentorship, and repetition equips companies to navigate unfamiliar business environments and thrive by delivering new products and services in competitive markets. Learning fosters innovative thinking and novel ideas, expanding a firm's ability to offer ingenious products or services by broadening its knowledge base.

Learning practices enable firms to access, develop, and exploit their organizational knowledge base, boosting their innovative capacity. The better a firm is at acquiring, generating, and using new and existing knowledge, the more creative its employees will be (Cabrilo & Dahms, 2020). Learning about the market also helps firms assimilate external knowledge beyond their borders, providing opportunities to adopt new practices and promote new products. Specifically, explorative and exploitative learning can enable organizations to innovate by enhancing current competencies and reinforcing accumulated experiences (Farzaneh et al., 2020). In fact, companies need to engage in learning behaviors such as environmental scanning and experimentation to gain up-to-date knowledge about external changes, explore new business opportunities, and adapt to emerging markets (Yoon et al., 2017).

Some studies stipulate that firms may only learn from their first product experience as they trapped into routine processes too quickly, ending the organizational learning process for creating new products (Michael & Palandjian, 2004). They argued that after a few NPD attempts, organizations struggle to learn from past experiences. Other studies, such as Li et al. (2013), found that exploratory learning positively influences new product performance, while exploitative learning follows an inverted U-shape. Their study of Chinese manufacturing firms concluded that learning does not always enhance NPD performance.

Despite these mixed findings, several studies provide empirical evidence of a positive and direct relationship between OL and NPD performance. For instance, Marzi et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review of NPD research and found that cultivating specific capabilities, such as environmental sensing, learning, coordination, and resource integration, enables a firm to adapt and respond more effectively to uncertainty. As a result, NPD efficiency and new product effectiveness improve. Zheng et al. (2022) observed that learning positively affects product innovation performance in Chinese firms. Additionally, Tian et al. (2021) conducted an empirical study in Ghana and concluded that learning has a positive significant effect on innovation performance regarding new products and services for SMEs. Patky (2020) conducted a systematic literature review of the association between OL, performance, and innovation, concluding that OL is a process through which organizations build their knowledge base and insights by analyzing past actions and future outcomes, particularly regarding new products. Considering these insights, OL is crucial for impacting NPDP, leading to the following hypothesis:

H2:OL positively affects NPDP.

IC, OL, and NPDPWhile numerous studies have shown a positive direct effect of IC on NPDP (Ali et al., 2020; Costa et al., 2014; Ghlichlee & Goodarzi, 2023) and financial and operational performance (Cao & Wang, 2015), another stream of research suggests that IC influences performance indirectly through employees' learning capabilities (Farzaneh et al., 2022). Some of these studies such as Land et al. (2012), in a large-scale survey involving 675 firms in the U.S., Germany, and Australia, found that social capital from extra-industry ties does not significantly impact exploitative learning. Similarly, Gima and Murray (2007) investigated technology ventures in China's industrial parks, finding that social capital does not necessarily enhance learning, and the relationship between learning and new product performance follows a U-shaped curve.

However, the significant indirect effect of various dimensions of IC on NPDP through organizational learning is somehow discussed in some research. In this light, You et al. (2021) suggested that well-educated employees with advanced cognitive and information-processing abilities can easily acquire and assimilate knowledge; therefore they can better understand novel information and integrate it innovatively. Using a multi-agent simulation model, Dong et al. (2023) argued that organizational members with unique knowledge, diverse ideas, and skills contribute significantly to OL by generating new ideas, exploring novel working methods, and converting them into new routines. Tzabbar et al. (2023) analyzed U.S. biotechnology firms and emphasized human capital's role in innovation, noting that well-educated employees can convert tacit knowledge into practical concepts and integrate knowledge in new ways to foster innovation.

To clarify more precisely, NPD requires tapping into external knowledge sources. According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), the diffusion of knowledge by knowledgeable and capable employees creates a basis for learning about opportunities, which strengthens firms' performance in the form of proposals for new products or services. Similarly, firms with well-established IC can identify market trends via substantial human capital (Ting et al., 2020), leading to improved product development. Since IC serves as a static stock that converts organizations into learning-oriented environments, it enhances firms' ability for OL. This, in turn, offers organizations the chance to circulate existing knowledge to create new forms and remain competitive by developing novel products. To explain in more detail, the knowledge and experience of individuals not only affect their ability to share knowledge, but also facilitate their ability to appreciate and absorb new knowledge, ideas, or approaches that lead to the development of novel products (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019).

Additionally, developing mutual relationships with various stakeholders and long-term communication with government agencies helps organizations identify and absorb market knowledge, which they use to meet customer needs with new products (Fliaster & Sperber, 2020). Through relational capital, employees can increase their relationships, networks, trust, and cooperation with various stakeholders, that may exhibit better information acquisition and resource allocation for new product development. This premise is rooted in the understanding that organizations operate in rapidly changing environments, so they need to monitor market trends and identify new opportunities. Therefore, social capital is expected to improve performance through knowledge acquisition, distribution, interpretation, and organizational memory.

Besides, Ganguly et al. (2019) emphasized that substantial relational capital enables employees to establish significant relationships with diverse partners, providing a platform to grasp market concerns and propose practical solutions. In this regard, Lopes et al. (2022) observed that SMEs with strong relational capabilities are more likely to gain diverse perspectives and resources to improv NPD performance. This suggests that companies with strong ties with stakeholders can more effectively access, generate, and combine new knowledge, and they benefit from a shared understanding needed to further develop its current products and services (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019).

The stronger a firm's structural capital, the more knowledge is embedded in its processes and information systems. It then reinforces the organizational capability to commercialize new knowledge in the form of new products. Efficient processes and non-hierarchical structures facilitate the integration of external knowledge and help identify emerging technologies and trends (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019). According to Farzaneh et al. (2020), organizations can share more knowledge and enhance their learning capability by focusing on structural capital through databases and information systems. Salangka et al. (2024) found that structural capital boosts enterprise learning capabilities, reduces decision-making costs, and minimizes misjudgments from inadequate information in Indonesian companies. Thus, well-organized knowledge in databases, processes, and systems facilitates knowledge sharing for generating new ideas (Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019).

Furthermore, Zhang and Lv (2015) discovered a complete intermediary effect occurs from learning on the relationship among human capital, structural capital, and technological innovation in Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms. As well as this, Chang et al. (2016) noted that human and organizational capital are vital resources for learning organizations striving for sustainable competitive advantages. Hence, despite the positive influence of IC components (staff, structure, and partnerships) on NPD, a crucial mechanism like OL may mediate the association of these two variables.

Considering these arguments, IC equips organizations with the fundamental abilities to learn what they need, share that knowledge, and apply it to enhance organizational performance by delivering new products. If well-established, IC fosters OL to explore and use the knowledge needed for NPD. Therefore, the quality of a company's employees, the systems it provides, and the knowledge it gains from external stakeholders will strengthen learning to better develop new products that meet market demands. Based on these studies, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3:The relationship between IC and NPDP is mediated by OL.

H3a:The relationship between human capital and NPDP is mediated by OL.

H3b:The relationship between relational capital and NPDP is mediated by OL.

H3c:The relationship between structural capital and NPDP is mediated by OL.

Innovation culture as a moderator for OL and NPDPInnovation culture represents an organization's blend of values, attitudes, beliefs, and ideas that fosters risk-taking, supports flexibility and change, promotes open communication, and motivates employees to look forward (Xie et al., 2019). Organizations with solid innovation cultures are more open to adopting and implementing new ideas. They are market-oriented and customer-focused, which enhances their ability to fulfill customer needs. Such firms prioritize R&D, which can improve the functionality of new products.

Research has recently focused on identifying cultural contexts that reinforce product innovation. However, only a few studies have considered innovation culture a catalyst for learning to generate new product ideas. Among them, some research such as Beglaryan et al. (2023) found no evidence to support the hypothesis of a mutual influence of innovation culture and OL on technological innovation.

However, studies such as Xie et al. (2019) highlighted the significance of innovation culture in learning behaviors for NPD, suggesting that innovative cultures enhance firms' learning abilities and enable them to generate novel ideas. Brettel and Cleven (2011) found that employees in organizations with high innovation cultures are more creative, open to new approaches, and more interactive with stakeholders. They are also inspired to challenge their assumptions, ultimately increasing their learning capacity and business value.

Moreover, Li et al. (2013) demonstrated the distinct influence of innovation culture on the relationship between OL and new product performance. Mehralian et al. (2022), in their study of the pharmaceutical industry, showed that organizations with a positive innovation culture provide employees with more opportunities to venture into new territories, broad their perspectives and knowledge scope, and seek new solutions to enhance performance. Sattayaraksa and Boon-itt (2016) found that organizational learning and innovation culture were positively related to the NPD process in Thai manufacturing firms. They argued that innovation culture encourages openness, risk-taking, and exploration of new opportunities, which can mitigate innovation constraints. Additionally, Ramdan et al. (2022) revealed that a culture encouraging creativity, risk-taking, and idea development is crucial for creating opportunities in the new product innovation process. Their study in Malaysia showed that effective exploration and exploitation competency will transpire when an innovation culture exists within the firm, and this will lead to the development of more creative and inventive goods that finally increases firm performance.

In fact, an innovation culture fosters collaboration and idea-sharing, encouraging employees to be creative and innovative while taking risks without fear of job loss (Jain et al., 2015). Not surprisingly, in organizations with a high degree of innovation culture, members can acquire new knowledge and share ideas, use knowledge resources effectively, and find new opportunities to meet customer needs. Given the above arguments, innovation culture characterizes firms that operate innovatively, take risks, and compete to learn more, simultaneously creating innovative consumer goods. Overall, organizations with a strong culture of innovation have a better chance of converting knowledge resources into innovative products.

H4: The positive effects of OL on NPDP are higher in firms having a higher level of innovation culture.

Research methodsResearch settingThis study focused on the pharmaceutical industry to test the proposed hypotheses, where product innovation is crucial and observable. Market analysis indicates that the Iranian pharmaceutical market has grown by around 15 % annually (Mehralian et al., 2022). By 2026, this market is expected to reach USD 0.8 billion, with a five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.4 %. Therefore, this sector provides an ideal environment to test the conceptual model due to its competitive nature, knowledge intensity, and the high costs of drug discovery and development (Farzaneh et al., 2022). IC plays a significant role in NPD for pharmaceutical companies due to their reliance on knowledge workers and their dependency on IC as a source of renewal and new drug development (Sharabati et al., 2010; Ge & Xu, 2020). Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual model used in this study to test the proposed hypotheses.

Sampling and data collectionThis research employed a survey method to collect data through a questionnaire. Secondary data was obtained from companies listed in the Iranian pharmaceutical industry for the period 2018–2019. Approximately 250 pharmaceutical companies in Iran produce finished products or active pharmaceutical ingredients. Contacting those that have launched at least one new product per year in the last three years, we examined a total of 107 firms. The proposed model and hypotheses were assessed using a questionnaire, the validity of which was first confirmed through interviews with some CEOs. Then, to reduce the single source and common method bias, data collection was conducted from different perspectives of the respondents. Surveys were conducted at two different time points to ensure rigorous analysis. In this regard, to control the cross-sectional bias, in the first round (T1), CEOs were asked to contribute information about their company (age and size) and IC. Six months later, in the second round (T2), R&D managers provided relevant data on their companies’ OL and NPDP. Between T1 and T2, middle managers were also invited to assess the level of innovation culture within their companies. Ultimately, 104, 107, and 671 complete questionnaires were received from CEOs, R&D managers, and middle managers.

MeasurementsTo develop measurement items, existing measures of IC, OL, innovation culture, and NPDP from previous studies were thoroughly examined. Expert panels reviewed the initial measurements through several interviews to assess their validity. A five-point Likert scale ranged from very low (score 1) to very high (score 5) was used to measure the items.

IC was assessed across human, structural, and relational capital. The measurement items were derived from the works of Youndt & Snell (2004), Youndt et al. (2004), and Mehralian et al. (2018). Three items were used to measure human capital, four for relational capital, and four for structural capital. CEOs were extracted to rate the level of IC within their organizations.

To measure OL, 13 items relating to the four dimensions of acquisition, distribution, interpretation of knowledge, and organizational memory were adopted from previous research (López et al., 2004; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2011). CEOs were asked to assess the extent to which their organization operates in a learning-focused environment.

Twelve items were adopted from the works of Ali & Park (2016) and O'Cass & Viet Ngo (2007) to measure innovation culture. Middle managers were asked to indicate the level of innovation culture in their companies. The company-level innovation culture scores were calculated by averaging the innovation culture scores (ICC) of all managers in their respective companies. ICC1 (0.078) and ICC2 (0.42) were used to aggregate the data to higher analytical levels and to extract the variance represented by group membership and group mean reliability.

NPDP was measured using scales from previous research (Jean et al., 2017; Tatikonda, 2007). Additionally, the number of new products developed by each firm was objectively measured using data published by the Ministry of Health and Science. Other variables, such as years of operation and firm size (the number of employees on the payroll), were controlled. R&D managers were asked to assess NPDP. Appendix 1 provides an overview of all variables and their corresponding measures.

Data aggregationChan (1998) introduced the concept of the direct consensus method, which we applied in our study. This method utilizes consensus within lower-level units to demonstrate the functional equivalence of a construct across different levels. Typically, this involves confirming agreement within groups at the lower level to justify aggregating scores to represent the higher-level construct. In our research, we adopted the direct consensus composition to argue that aggregated scores of innovation culture might reflect the organization's overall innovative capacity. We compiled responses from middle managers on innovation culture at the firm level. The median rwg value was 0.76, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.70, indicating high consistency in participants' responses within the firm. The ICC1 value was 0.15, surpassing the 0.10 cut-off (Bliese, 2000), indicating sufficient variance explained by the middle managers. With an ICC2 value of 0.73, which meets the reliability threshold of 0.70 (Bliese, 2000), our criteria for aggregating data on innovation culture were met.

Data analysis and resultsDescriptive statisticsThe sample comprised approximately five middle managers from each firm. After data cleaning and matching, 104 valid questionnaires were obtained, yielding a response rate of 41 %. Eighty percent of respondents held a doctorate, and 20 % had a master's degree. Nearly 40 % had 3–10 years of experience. The companies surveyed had between 60 and 896 employees and had been in operation for 5 to 63 years.

Measurement modelThe measurement reliability for the constructs was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficients, which evaluates how well a block of indicators measures its corresponding latent construct. The results ranged from 0.71 to 0.87, which exceeds the recommended level of 0.7 proposed by Hair et al. (2011). To assess the reliability of each dimension, the factor selection criterion proposed by Kaiser (1958) (an eigenvalue above one along with a total factor loading value greater than 0.5) was calculated. Convergent validity was examined using the factor loadings and the significance of the t-value. In the case of multiple corresponding items for the constructs and significant associations of each item's loading with its underlying factor (t-values >1.96 or <-1.96), the average variance extracted (AVE) must be greater than or equal to 0.50, and the factor loading values must be greater than the recommended value of 0.60 (Hair et al., 2011). The factor loadings of all measurement items, along with Cronbach's alpha and AVE, are presented in Appendix 1.

Moreover, to make sure there was no multicollinearity for some variables with high correlations, the variance inflation factor (VIF) tests were conducted (Kline, 2015). The VIF results indicated no multicollinearity, and these values were favorable and low (VIF = 1.041; p < 0.001). Using the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981), discriminant validity was evaluated across latent variables by comparing each AVE with the squared correlation between constructs. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and correlation matrices between the variables, are shown in Table 1.

Means, standard deviation, and correlations, and square roots of average variance extracted.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Activity | 38.12 | 16.76 | 1 | |||||||

| Number of Employees | 365.03 | 173.66 | 0.27 | 1 | ||||||

| Human Capital | 3.13 | 0.79 | 0.003 | -0.29⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||

| Relational Capital | 3.5 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.122 | .51⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||

| Structural Capital | 3.57 | 0.66 | 0.053 | -0.043 | .47⁎⁎ | .44⁎⁎ | 1 | |||

| OL | 3.11 | 0.67 | -0.17 | -0.073 | .54⁎⁎ | .51⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| NPDP | 3.29 | 0.71 | 0.068 | 0.045 | .49⁎⁎ | .52⁎⁎ | .46⁎⁎ | .48⁎⁎ | 1 | |

| Innovation Culture | 3.4 | 0.59 | -0.044 | -0.023 | .56⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎ | .44⁎⁎ | .61⁎⁎ | .49⁎⁎ | 1 |

*P < 0.05 (2-tailed) was regarded as the significance level.

The constructs' psychometric properties were tested via CFA using LISREL 8.5. The CFA assessed the unidimensionality of measurement scales and the model's fit. A four-factor CFA model, including IC, OL, innovation culture, and NPDP, was tested to evaluate convergent and discriminant validity across all constructs. The model demonstrated an acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992). Furthermore, three- and two-factor models were examined omitting innovation culture and NPDP, respectively. Comparing the four-factor model to the three- and two-factor models, the four-factor model exhibited better fit, resulting in the discriminant validity of the constructs. Subsequently, the descriptive statistics including the means and standard deviations, as well as the correlation matrices between the variables were analyzed, which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 indicates that human capital (r = 0.54, p < 0.01), relational capital (r = 0.51, p < 0.01), and structural capital (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) all positively correlated with OL. Additionally, OL was positively correlated with NPDP (r = 0.48, p < 0.01). A significant correlation was also found between innovation culture and OL (r = 0.61, p < 0.01) and NPDP (r = 0.49, p < 0.01). These results strongly support the reliability and discriminant validity of the constructs.

Hypotheses testingTo test the hypotheses, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted using SPSS 21. This analysis helps determine how specific variables contribute to the dependent variable after all other variables have been accounted for, especially with regard to the existence of moderator effects (Evans, 1985). As shown in Table 2, for the M1 and M2 models, the impacts of the independent variables on the dependent variables were analyzed. The control variables were first introduced into the first model (M1). This model indicates that years of activity significantly affected OL (β = -0.16*, p < 0.10). However, the number of employees did not have a significant relationship with OL (β = 0.005). In the next step (M2), IC was introduced as an independent variable. The results show that IC had a positive and significant impact on OL, with a significant proportion of the variance in OL explained by human capital (β = 0.28⁎⁎, p < 0.001), relational capital (β = 0.33⁎⁎, p < 0.001), and structural capital (β = 0.28⁎⁎, p < 0.001). Therefore, hypotheses H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported, demonstrating a significant direct effect of IC on OL.

Regression analysis on the hypothesized associations of IC with OLa.

| Variables | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Employees | .005 | .003 | .05 | .06 | .03 |

| Years of Activity | -0.16* | -0.12⁎⁎ | -0.16⁎⁎⁎ | -0.17⁎⁎ | -0.13⁎⁎ |

| Human Capital | .28⁎⁎ | .24⁎⁎ | |||

| Relational Capital | .33⁎⁎ | .27⁎⁎ | |||

| Structural Capital | .28 ⁎⁎ | .25⁎⁎ | |||

| R2 | .031 | .31 | .32 | .35 | .39 |

| Adjusted R2 | .029 | .29 | .31 | .34 | .36 |

| ANOVA F | 13.61⁎⁎ | 19.5⁎⁎ | 21.16⁎⁎ | 24.12⁎⁎ | 31.27⁎⁎ |

Table 3 presents the impact of the number of employees, years of activity, IC, OL, and innovation culture on NPDP. In Model 1 (M1), years of activity were significantly correlated with NPDP (β = -0.18*, p<0.10), while the number of employees had no significant effect on NPDP (β = 0.09). In Model 2 (M2), IC was positively and significantly correlated with NPDP (β = 0.2⁎⁎⁎, p<0.001). Next, Models 3 (M3) and Models 4 (M4) evaluated the mediating effect of OL on the relationship between IC and NPDP. Given the significant relationship between OL and NPDP (β = 0.26⁎⁎, p<0.001), IC also showed a positive relationship with NPDP even after entering OL in the model. Thus, H2 and H3 were supported, indicating that OL not only has direct effects on NPDP but also mediates the relationship between IC and NPDP.

Results of Regression Analysis Which Predict NPDPa.

| Variables | NPDP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | |

| Number of Employees | .09 | .08 | .06 | .05 | .06 | .04 |

| Years of Activity | -0.18* | -0.17⁎⁎ | -0.14* | -0.16⁎⁎ | -0.12* | -0.19⁎⁎ |

| Intellectual Capital | .27⁎⁎ | .25⁎⁎ | .26⁎⁎ | |||

| OL | .23⁎⁎ | .26⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ | |||

| Innovation Culture | .31⁎⁎ | .25⁎⁎ | ||||

| OL* Innovation Culture | .29⁎⁎ | |||||

| R2 | .13 | .14 | .13 | .53 | .54 | .38 |

| Adjusted R2 | .14 | .15 | .14 | .52 | .55 | .37 |

| ANOVA F | 17.3⁎⁎ | 22.68⁎⁎ | 25.38⁎⁎ | 56.41⁎⁎ | 65.9⁎⁎ | 39.16⁎⁎ |

Finally, Models 5 (M5) and 6 (M6) aimed to clarify whether innovation culture moderates the relationship between OL and NPDP. The results showed that innovation culture significantly and positively influenced NPDP (β = 0.31⁎⁎, p<0.001). Accordingly, the role of OL in NPDP (β = 0.22⁎⁎, p<0.001) remained significant even after introducing the interaction term (OL * innovation culture). Hence, H4 was confirmed, indicating that innovation culture moderates the relationship between OL and NPDP.

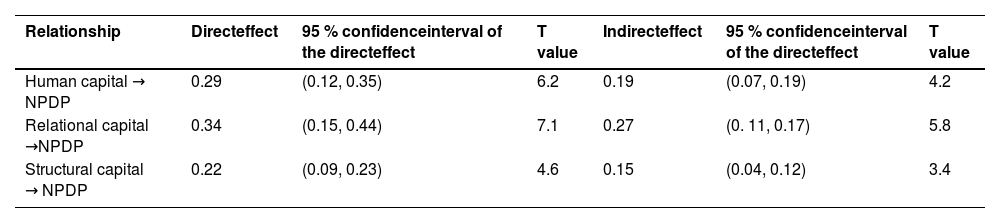

Post hoc analysisThe bootstrapping technique in Smart-PLS was utilized to analyze the mediating effect of DCs on the relationship between IC components and NPDP. PLS-SEM is a robust technique that has been increasingly used in social science research over the past decade (Hair et al., 2017). The measurement model satisfactorily fits the data according to fit indices (χ² (450) = 1125, p<0.001; RMSEA = 0.04; GFI = 0.88; CFI = 0.96). As shown in Table 4, the direct effects of IC dimensions on OL were positive and significant, as was the relationship between OL and NPDP. The results revealed a positive indirect effect of OL on the IC dimensions-NPDP relationship. Specifically, relational capital (β = 0.27) had a more substantial effect on NPDP compared to human capital (β = 0.19) and structural capital (β = 0.15). Hence, the mediating effect of OL in the relationship between IC dimensions and NPDP is classified as complementary mediation, confirming hypotheses H3a, H3b, and H3c.

Analysis for the mediation effect of OL between IC components and NPDP.

In addition, the proposed moderated effect was examined using the PROCESS macro bootstrapping method (Hayes, Preacher, & Myers, 2012). A 5000-fold resampling confirmed that innovation culture moderates the effects of OL on NPDP. Further, to interpret the interaction results, we graphed the moderation effect at one standard deviation above and below the mean for OL and innovation culture. We plotted the moderation effect for OL and innovation culture at one standard deviation above and below the means to interpret the results (see Fig. 2).

DiscussionThe existing literature has highlighted the interrelation between IC, OL, and NPDP. However, empirical analyses in this domain have not offered a comprehensive understanding of these relationships. Adopting the RBV, this study focuses on the mechanisms through which IC influences NPDP. Four hypotheses were tested using data from the pharmaceutical industry, leading to several key findings.

Theoretical implicationsThis study contributes to the existing theory within the field of IC because it represents one of the first attempts to provide an overarching view of IC, OL, innovation culture, and NPD within the context of the pharmaceutical industry. The findings emphasize the significant role of IC in a firm's capacity to acquire new knowledge and uncover fresh ideas. One possible reason could be that knowledgeable and experienced employees, strong ties with stakeholders, and systematic processes and databases support learning in firms. This finding argues for the RBV, which provides organizations with more opportunities to transform their static knowledge assets, that is IC, into dynamic ones, for example OL. In particular, the knowledge base of pharmaceutical companies relies heavily on internal and external research and development activities. As a result, knowledge assets play a critical role in determining how competitive these companies are (Dahiyat et al., 2023).

This relationship can be explained in three ways. First, organizations with a robust human capital can facilitate collective action more effectively because their employees possess the necessary skills, competencies, and training for exploratory learning. This aligns with previous research (Cabrilo & Dahms, 2020; Duodu & Rowlinson, 2019), providing that the higher human capital, the higher organizational learning. Indeed, as far as human capital is concerned, organizations should not only enhance employees' technical or functional skills, but also nurture their ability to network, collaborate, and share knowledge. Insufficient OL capacity may effectively improve the knowledge reservation, the burden of employees’ learning, and digesting of redundant internal knowledge. This, in turn, impacts performance positively (Pi et al., 2021).

Second, organizations with high social capital are adept at establishing strong customer connections, which is essential for acquiring market knowledge. Robust collaboration with partners gives everyone a shared vision and a comprehensive view in terms of the emergence of new ideas (Xu et al., 2019), thus firms benefit from organizational exploratory learning. The more social capital available to a firm, the more it can invest in identifying market opportunities, leading to improved product quality and performance (Attar et al., 2018). This finding supports previous research (Liu et al., 2010; Xin et al., 2020).

To build further from here, we can conclude that in the rapidly evolving field of the pharmaceutical industry, innovation flourishes within dynamic knowledge networks of industry professionals. Companies must establish collaborative partnerships and expand their networks to enhance competitiveness and capture value. Pharmaceutical firms aim to establish long-term relationships with regional decision-makers to gain clinical and economic advantages through innovation (Huang et al., 2021). To support this notion, Subramanian and Vrande (2019) highlighted that relational capital significantly influences product innovation by reducing the likelihood of discontinuing new product development in biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors. Third, the richer the knowledge repository, the greater the chance that the firm will keep its knowledge up to date. Employees rely on each other's knowledge, and thus share insights spontaneously within the organization through supportive systems and processes. Moreover, it is a given that if the organization has a positive culture of trust, employees are more likely to communicate, which in turn leads to knowledge sharing (Mehralian et al., 2018). A high level of interpersonal trust in a firm not only encourages open discussion, understanding of work-related problems, and effective communication among team members, but also diminishes barriers among individuals to talk about the problems they encounter. This helps employees acquire new knowledge and refine existing knowledge, showing the contribution of structural capital to OL that expands on earlier studies (Liu, 2017). This study confirms the findings of previous research showing that human, structural, and relational capital positively contribute to OL (Afshari & Nasab, 2020). Our findings are also backed up by a rigorous research design involving that product development in the pharmaceutical industry depends on experience from prior exploratory alliances (Dong and Yang, 2015).

The second theoretical implication of this study relates to the contributing role of OL as a potential mediator in the relationship between IC and NPDP. It is concluded that the relationship between IC and NPDP is not simply linear; OL significantly influences this link. Consistent with studies such as Attar et al. (2019), who argued that IC enhances operational performance, this study adds to such findings by demonstrating that IC promotes NPDP through OL. This is in line with You et al. (2021), who suggested that while IC provides a foundation for new product development, its effectiveness must be considered alongside knowledge learned from internal or external sources.

The third theoretical implication of this study concerns the role of innovation culture in the relationship between OL and NPDP. Previous research has primarily focused on the direct impact of OL on NPDP (Saban et al., 2000) but rarely examined the interaction through innovation culture. Current research found that OL not only has a direct impact on the NPDP of pharmaceutical companies, but also innovation culture influences this relationship. Consistent with previous research such as Attar et al. (2018), the findings revealed that organizational culture shapes employees' beliefs and perceptions regarding knowledge sharing, and it is a conduit for knowledge creation. The findings offer insights regarding innovation culture that fosters participative decision-making, risk-taking, rewarding success, team decision-making, and open communication. Such culture enriches companies by fostering the absorption and integration of knowledge and creating a willingness to engage in idea generation and development, ultimately enhancing the capability to new product development (Farzaneh et al., 2020). Thus, this study provides new insights into the interaction between OL and NPDP, offering valuable ideas on the moderating role of innovation culture. This result is related to the contingency view, which argues for the consideration of contextual factors in organizational studies.

Practical implicationsThe study's results have several practical implications for managers in the pharmaceutical industry. Given that these companies are knowledge-intensive, their innovation and competitive performance rely heavily on the knowledge they acquire. Managers should prioritize soft capital, such as organizational values, culture, experience, and human skills, to enable their firms to absorb the market knowledge and insights necessary for exploring production opportunities. Such valuable capital would empower firms to leverage existing knowledge and explore the necessary knowledge to effectively identify market expectations and launch new products.

Additionally, managers and policymakers should enhance OL to improve the acquisition of in-depth knowledge and develop value-added products. This sheds light on the impact of OL on daily business and social concerns. When individuals share their knowledge, there are more opportunities for new combinations of complementary knowledge, which increases firms’ chance of developing new products to meet market demand. Furthermore, dissemination of knowledge helps employees use their knowledge better, which is an excellent way to strengthen NPD outcomes. Managers should seek the best approaches to enhance OL that reinforce acquisition of knowledge about critical events and dissemination of the results of knowledge analysis to improve NPD performance. Therefore, research findings offer that because the NPD process is inherently knowledge-intensive, the firm's competitive capabilities depend dramatically on acquiring higher levels of knowledge.

From a practical standpoint, managers should also foster a positive organizational culture to have a greater chance of spreading best practices among employees through teamwork. Establishing a risk-taking culture that encourages collaborative decision-making facilitates the attraction and diffusion of knowledge within the firm. Accordingly, managers should inspire employees to explore, learn, and share knowledge, which will help companies identify new ideas and develop specialized products.

Limitations and directions for future researchTo address the limitations of this study, future research should consider the following issues. First, when it comes to global standards, significant developments can be observed in Iran's pharmaceutical industry. However, conducting the present study in this industry could not avoid some limitations in terms of generalization of the results. Undoubtedly, examining the model of the study in other contexts would make the results more generalizable. Second, future research should include additional variables (e.g., market turbulence) affecting the IC-NPDP relationship to explore other mechanisms through which IC enhances NPDP. It is suggested that future studies consider different external variables affecting the model variables, the concurrent collection of the measures, and other important organizational factors with a focus on the context of the pharmaceutical industry. Third, this study focused on the perspectives of senior managers concerned with the issue. Future research could incorporate employee perspectives as well to provide a broader understanding. Fourth, this study explored the impact of IC components on OL. Further research can analyze the relationship between IC as a bundle (human, relational, and structural capital) and the components of OL (knowledge acquisition, distribution, interpretation, and organizational memory). Finally, the current research examined NPDP as a single output of OL. It is suggested that future studies elaborate tangible performance indicators to explicitly analyze the impact of OL on organizational outcomes.

CRediT authorship contribution statementGholamhossein Mehralian: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mandana Farzaneh: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Nazila Yousefi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology. Radi Haloub: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.