The literature on the research–practice gap in agriculture has evolved significantly in recent decades. Although there is a well-established body of work on how farmers adopt agricultural research outcomes and the factors that influence their adoption, research on how researchers perceive the process of transferring their results to practical applications, along with the factors that facilitate or hinder this process, remains inadequate. This study addresses this gap by conducting a systematic literature review of empirical studies on knowledge transfer and its determinants from the perspective of agricultural researchers, covering publications from 1960 to 2024. It offers two key contributions: first, an original taxonomy of the channels through which agricultural research is transferred to farmers, and second, an integrative conceptual framework that links knowledge transfer to three categories of influential factors, related to researchers’ individual characteristics, the organizational context within research institutions, and the external environment. Based on the findings, a research agenda has been developed to serve as a foundation for future investigations into persistent gaps in the field. The findings hold value for both academic and practitioner communities as they provide deeper insights to improve the understanding and practice of knowledge transfer in agriculture.

The emergence of the knowledge society era in the 1990s (Lytovchenko et al., 2022) has caused a transition from agrarian and industrial societies to a knowledge-based society primarily stemming from the widespread availability and abundance of complex and massive data, as well as revolutionary advances in digital and information and communication technologies (ICTs) (Bilan et al., 2023). The agricultural sector has not been immune to these changes, with recent years witnessing a wave of modernization driven by the widespread adoption of next-generation digital technologies (NGDTs), such as artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IoT), big data (BD), and nanotechnology (Purnama & Sejati, 2023). Rapid scientific and technological advances in the agricultural sector have given rise to a spectrum of terms to characterize these changes, variously labeled as “agriculture 4.0″, “digital agricultural revolution,” “connected agriculture,” “digital farming,” and “AgTech” (Jakku et al., 2023; Martin & Schnebelin, 2023). With automated irrigation systems, GPS-guided tractors, aerial imagery, soil sensors for AI-driven crop monitoring, and nanotech-enhanced fertilizers, the possibilities for innovation in agriculture are unlimited (Danai-Varsou et al., 2023; Nemade et al., 2023). Consequently, farmers are becoming data-driven decision-makers (Rozenstein et al., 2024). The integration of advanced predictive analytics, fueled by comprehensive and high-quality data, empowers farmers with the capability to access up-to-date and relevant information on various aspects, such as weather forecasts, market dynamics, pricing of agricultural inputs (e.g., seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides), and advanced farming techniques (Farooqui et al., 2024; Karunathilake et al., 2023; Rozenstein et al., 2024). Overall, these advances empower farmers to make more informed decisions, effectively manage on-farm production, and proactively optimize farm efficiency.

Agricultural innovation begins in research laboratories and institutions, where innovative ideas and cutting-edge technologies are developed. Research and development (R&D) in agriculture remains a priority for diverse stakeholders, including government bodies, public or private research institutions, and higher education institutions (HEIs). (Anandajayasekeram, 2022; Yongabo & Göktepe-Hultén, 2021). In the context of research promotion, funders are focused on bolstering the scientific productivity of researchers and promoting research excellence among scholars and HEIs (Arnott et al., 2020). However, despite the involvement of numerous researchers in advancing knowledge, the agricultural research community often encounters difficulties in transferring its research results beyond the confines of the institution (Ansari et al., 2016; Hočevar & Istenič, 2014; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012; Yaakub et al., 2011). Practical applications of agricultural research remain suboptimal. Scientific research outcomes are often relegated to forgotten drawers and are underutilized or even disregarded altogether in agricultural practice (Koutsouris, 2012). Consequently, the transfer of evidence-based knowledge to actionable outcomes in agriculture remains a complex and multifaceted challenge (Chen & Li, 2022; McCown, 2001; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012).

Researchers face challenges in integrating farmer-centric needs within research projects, whereas farmers perceive scientific research as distant or irrelevant to their agricultural practices (Bayissa, 2015a). The divergence of priorities between researchers, driven by a quest for theoretical knowledge and progress, and practitioners geared towards solving concrete, real-world problems, hinders the alignment of scientific results with field applications (Amara et al., 2019; Caplan, 1979), especially since the process of generating scientific knowledge is highly time-consuming and can span several years. Researchers spend time in comprehensive studies, whereas practitioners seek timely, pragmatic, and tangible solutions to address immediate issues (Amara et al., 2019; Cruz et al., 2022; Tucker & Lowe, 2014). Consequently, an ever-widening gap persists between the scientific and agricultural communities (Abereijo, 2015; Carayannis et al., 2018; Dutrénit et al., 2016; Higgins, 1991; McCown, 2001; Romańczyk et al., 2012). This research–practice gap restricts the effective transfer of innovative solutions from scientific knowledge to actionable practices (Bansal et al., 2012; Böckel et al., 2021; Carter, 2008; Neal et al., 2015; Tucker & Lowe, 2014; Tucker & Parker, 2014), begging the important question of how to bridge the research–practice gap in agriculture to enhance the effective transfer of scientific findings among farmers. Although research provides significant insights into how farmers adopt new agricultural practices and what factors influence their decisions, less is known about how researchers perceive the process of transferring their findings to practical applications in agriculture (Cruz et al., 2022). This study systematically reviews the state of knowledge transfer from researchers’ perspectives, with a two-pronged aim: first, to develop a taxonomy of knowledge transfer channels between agricultural research and farmers, and second, to identify, from the researchers’ perspective, the factors that either facilitate or hinder this transfer. To this end, this study explored three key research questions.

- 1.

How has the research–practice gap been conceptualized in agricultural literature?

- 2.

What formal and informal channels do agricultural researchers use to transfer knowledge to farmers?

- 3.

What factors serve as facilitators or barriers to closing this gap?

To address these research questions, this study employs a rigorous and comprehensive systematic literature review (SLR), analyzing a corpus of articles spanning >60 years. Based on the findings of this extensive analysis, it proposes a research agenda that outlines key recommendations and promising future research avenues.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 provides an in-depth overview of the methodological protocols used in this study, elaborating on the SLR method used to identify, select, analyze, and synthesize the relevant literature of the past 64 years. Section 2 presents the descriptive and analytical findings, based on which an integrative conceptual framework of knowledge transfer and its determinants within the agricultural sector are developed. Finally, Section 3 highlights the key contributions, outlines the research agenda for future studies, and addresses its limitations.

MethodRationale for using the systematic literature reviewThis study adopted the SLR method to provide a state-of-the-art review of knowledge transfer in the agricultural sector. Unlike other types of reviews (e.g., narrative literature reviews and scoping literature reviews), the SLR is a rigorous, exhaustive, replicable, and transparent research method that involves a structured process of identifying, selecting, analyzing, and summarizing existing research on a specific topic (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009; Sauer & Seuring, 2023).

Such an approach is used for several reasons. Knowledge transfer is a multidisciplinary field often subject to a wide range of research conducted across different disciplines and scattered across diverse publications and journals. Many articles on this topic have been published in scientific journals that do not specialize in agriculture. Second, several studies have focused on the gap between agricultural researchers and farmers, their results are not linked to an integrative conceptual framework. Because current knowledge has been developed in silos, this does not allow for the development of a holistic view of state-of-the-art knowledge transfer from agricultural researchers to farmers. Third, research on knowledge transfer between agricultural researchers and practitioners in the agricultural milieu has experienced a surge of interest since the development of diffusion models for agricultural innovation in the early 1960s (Rogers, 1962). As a result, the extant literature on this topic has failed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the gap between these two communities of practice. An SLR might be an efficient method of organizing a state-of-the-art knowledge transfer from agricultural researchers to farmers, providing a comprehensive overview that cannot be obtained through a single or few studies and fostering potential avenues towards novel breakthroughs and advances in both theory and practice.

In 2016, a literature review (not an SLR) was conducted by Elueze on knowledge translation in agriculture, which primarily intended to examine the knowledge transfer process in agriculture following the Lavis knowledge transfer framework (Lavis, 2003). This framework is based on five cornerstones: the message, target audience, messenger, KT process and support system, and evaluation of the effect of the knowledge transferred. The findings of this study highlight that agricultural researchers are the main messengers of knowledge transfer to farmers, and that, notwithstanding a variety of potential users of agricultural knowledge, the most popular target audience for researchers is farmers. The author called for more studies focusing on knowledge transfer to policymakers for better evidence-based policy decisions, and a further explication of the role played by libraries and information science professionals in agriculture research knowledge transfer. However, Elueze (2016) did not, like the present study, aim to identify the knowledge transfer channels used by agricultural researchers to reach farmers nor build an integrative conceptual framework linking knowledge transfer from agricultural researchers to farmers to its determinants.

Research questionsThis SLR aimed to provide a comprehensive synthesis of existing research that satisfies our inclusion and exclusion criteria, offering a detailed understanding of how the research–practice gap is perceived and addressed within the agricultural community. Specifically, the systematic literature review attempts to answer the following questions: 1) How has the gap between research and practice been conceptualized in the agricultural literature? (2) What are the formal and informal means of knowledge transfer used by agricultural researchers to reach farmers? 3) What are the levers and impediments, from the perspective of agricultural researchers, that may explain this gap?

Search strategyThe SLR was performed using the SALSA framework (Booth et al., 2013; Grant & Booth, 2009), which provides an explicit, transferable, and reproducible procedure for conducting it (García-Holgado et al., 2020; Mengist et al., 2020; Yeboah et al., 2023). It encompasses a four-stage process—search, appraisal, synthesis, and analysis (SALSA)—the first of which is the “search stage” that aims to gather a preliminary list of publications to analyze. It deals with search strategy and delivery, notably the definition and construction of the keyword chain and the choice of relevant databases to collect information. Second, the “appraisal stage” involves two basic steps: 1) identifying the relevant articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 2) assessing the quality of selected articles. Third, the “synthesis stage” consists of both extraction and classification of relevant data from selected papers. Finally, the “analysis stage” involved assessing the synthesized data, extracting significant information and drawing conclusions from the selected articles. Here, the SLR was analyzed against the SALSA framework described next.

Stage 1: searchBooth et al. (2013) advise that any literature search risks missing relevant items given the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to conduct the search. To address this problem, a search was conducted using the broadest possible terms related to the knowledge gap between agricultural researchers and farmers. An expert librarian corroborated the choice of the relevant databases. The search encompassed three multidisciplinary electronic databases –Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics), ABI/Inform Global (ProQuest), Business Source Premier (EBSCO) – and two specialized electronic databases – CAB Abstracts (OVID), Eric (EBSCO). These databases were selected because they provide a large coverage of the relevant literature. The fact that the concept of the knowledge gap between research and practice has been the subject of contributions from various research fields (e.g., Chi, 2021 – education; Newnam et al., 2020 –medicine; Greene, 2021 – psychology; Ivanov et al., 2021 – management) justifies the use of multidisciplinary databases. The databases were accessed from the websites of the authors’ university libraries. The expert librarian also participated in building a keyword chain. The list of keywords was obtained by snowballing, which included bibliographic referencing, back-referencing (reviewing the references of included studies), and citation tracking (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006). The keyword chain combined three key concepts. The first key concept referred to the theme of knowledge transfer, the second included keywords related to academic and scientific fields, and the third included keywords related to agriculture. These concepts and their synonyms were used in various combinations with Boolean operators “AND” (to obtain results that include all search terms simultaneously) and “OR” (to include alternative terms or synonyms). The following keywords were used to identify relevant articles.

Transfer* OR “knowledge transfer” OR diffus* OR “knowledge diffusion” OR disseminat* OR “knowledge dissemination” OR translat* OR “knowledge translation” OR uptake* OR “knowledge uptake” OR exchange OR “knowledge exchange” OR shar* OR “knowledge sharing” OR “knowledge circulation” OR “knowledge spread” OR “know-how transfer” OR “knowledge transmission” OR gap OR “knowledge gap” OR “research–practice” OR “research–practice gap” OR implement* OR “knowledge implementation” OR knowledge application* AND Research* OR professor* OR scien* OR academic* OR “agricultural researcher” OR scholar* OR “agricultural researchers” OR “scientific community” OR “scientific communities” OR faculty member* OR facult* OR “research institutes” OR universit* OR higher education institution* OR HEI* OR research center* AND agricult* OR farm* OR farm worker* OR agricultural worker* OR rural sector OR rural* OR agricultural laborer* OR rural farm resident* OR agricultural business OR agricultural communit* OR agricultural producer* OR agricultural agencie*

All articles from each database were indexed using Endnote software. Then, an examination of all identified articles was carried out. After eliminating 732 duplicate studies, 5837 potentially unique eligible articles for this systematic literature review were obtained (Table 1).

Results of electronic databases search.

| DATABASE | SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES IDENTIFIED | DUPLICATES | UNIQUE ITEMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| MULTIDISCIPLINARY DATABASES | |||

| Web of science (Clarivate Analytics) | 1437 | 289 | 1148 |

| ABI/INFORM global (ProQuest) | 1523 | 91 | 1432 |

| Business Source Premier (EBSCO) | 991 | 42 | 949 |

| SPECIALIZED DATABASES | |||

| CAB (OVID) | 2150 | 268 | 1882 |

| Eric (EBSCO) | 468 | 42 | 426 |

| TOTAL | 6569 | 732 | |

This stage mainly involved the application of the exclusion and inclusion criteria established with respect to the research questions. These criteria, along with a description of the study rationale, are presented in Table 2.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria.

| CRITERIA TYPE | CRITERIA | RATIONALE |

|---|---|---|

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | ||

| Type of document | The selected documents consist of scientific papers published in peer-reviewed journals, emphasizing the importance of ensuring the reliability of the findings. | The articles are published in a scientific peer-reviewed journal, which notably excludes books (and book chapters), essays, master theses, doctoral theses, research notes, dissertations, and conference proceedings, etc. Additionally, for inclusion in the review, the full-text version of the articles had to be accessible to ensure no broken links or limitations to accessing the complete content. |

| Focus area | The primary focus of the selected articles is on the knowledge transfer within the agricultural field. | The articles that specifically discuss the concept of knowledge transfer or the gap between research and practice in the agricultural context were chosen. Additionally, the selected articles had to offer substantial information to facilitate a comprehensive review of the factors influencing knowledge transfer in agriculture. They were to specifically target the research perspective when examining the influential factors of knowledge transfer from agricultural researchers to agricultural community. |

| Unit of analysis | The unit of analysis for this study encompasses individual researchers, universities, research institutions, and other organizations involved in producing scientific research within the agricultural field. | The unit of analysis for this study was selected strategically. This decision was guided by our specific focus on identifying the barriers and facilitators that operate upstream in the knowledge transfer process, particularly at the level of knowledge producers (researchers). |

| Language | The selected articles are published in English. | Only articles written in the English language were considered for inclusion in the SLR. This decision was taken because a significant proportion of influential scientific publications in scholarly journals are published in English. By limiting the review to English-language articles, the study aimed to encompass a substantial body of relevant and impactful research in the field of agricultural knowledge transfer (Duszak & Lewkowicz, 2008; Henshall, 2018). |

| Temporality | The selected papers were published between January 1960 and June 2024 inclusively. | The rationale behind selecting 1960 as the reference point for our search is to trace the development of literature on knowledge and innovation diffusion within the agricultural domain, starting from the seminal work of Rogers (1962). The choice of 2024 as the concluding year was because it was the most recent year. Consequently, this time frame was expected to encompass the great majority of publications related to the subject matter under review. |

| Method | All types of empirical papers, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies, were included. | By focusing on empirical studies, this SLR aimed to identify the determinants of knowledge transfer considered across various contexts and settings and highlight the most recurrent predictors of knowledge transfer in agriculture. |

| EXCLUSION CRITERIA | ||

| Type of document | All published studies other than articles published in scientific journals, are excluded from the SLR, namely books (books and book chapters), essays, research notes, conference proceedings, letters, short stories, dissertations, doctoral theses, grey literature, including non-peer-reviewed articles, etc.Articles not available in full text were also excluded. | The exclusion of these types of documents was carried out based on the consensus among several authors that important scientific contributions are primarily published in international peer-reviewed journals, which tend to have high impact on the field (Elsbach & Van Knippenberg, 2020; Post et al., 2020). Therefore, to uphold the quality of the study, only peer-reviewed articles from scholarly journals were included in the review. |

| Focus area | Articles that do not primarily address knowledge transfer within the agricultural field were excluded | |

| Unit of analysis | Articles that address units of analysis not directly involved in the production of scientific research within the agricultural field (such as farmers, producer unions, etc.) were excluded. | |

| Language | Articles published in languages other than English were excluded. | |

| Temporality | Papers published outside the specified timeframe (before January 1960 and after June 2024) were excluded. | |

| Method | Non-empirical studies (all other methods (e.g., theoretical/conceptual)) were excluded. | |

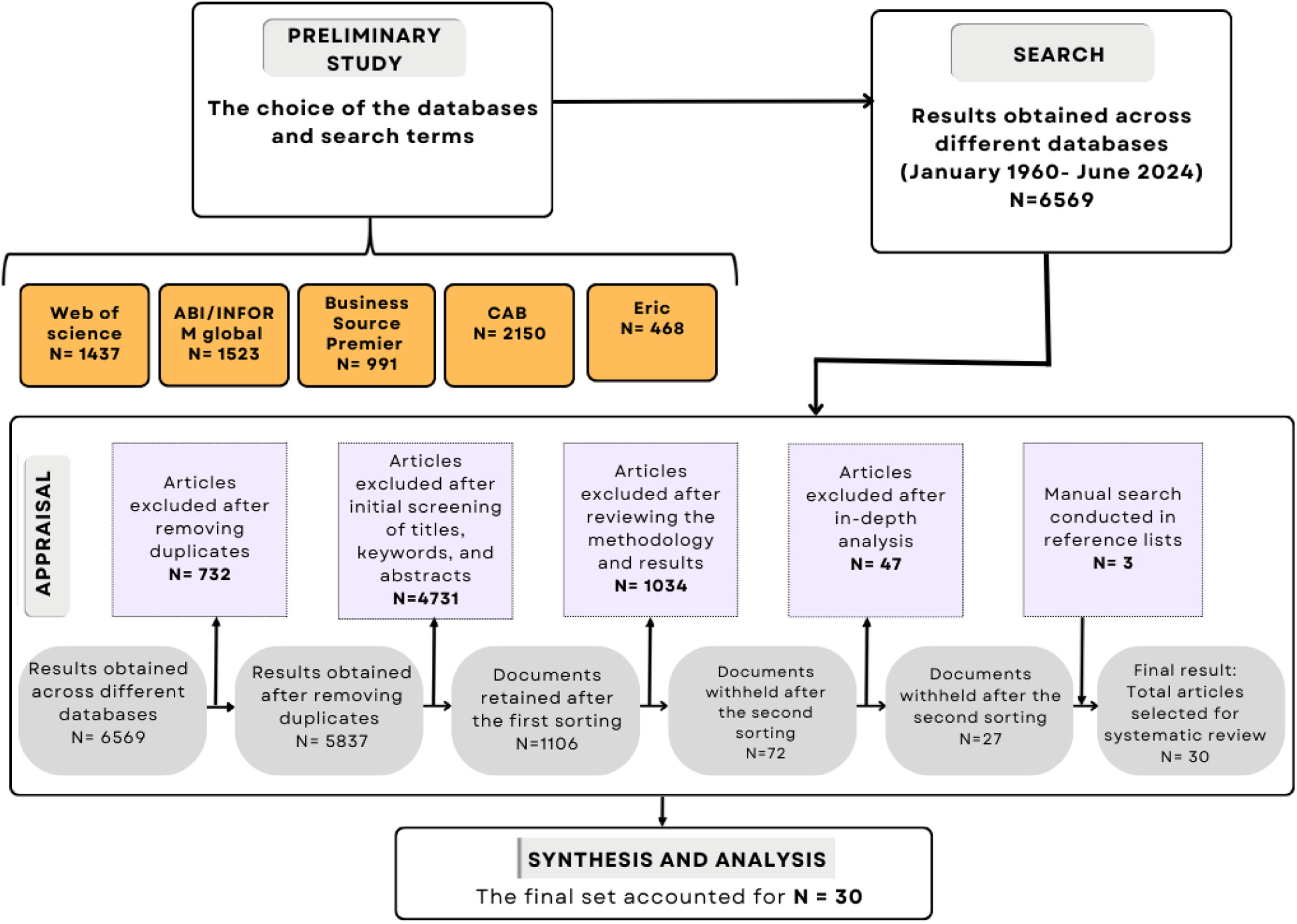

Each article was sequentially evaluated based on these criteria and was excluded if any criterion was not met. The sifting process had four stages. All titles, keywords, and abstracts were reviewed to eliminate publications that did not focus on the transfer of agricultural knowledge from researchers to farmers. This first screening procedure enabled the exclusion of 4731 articles that did not meet all the criteria. Subsequently, a second, deeper shifting based on a reading of the methodology and results of the study was performed on the 1106 articles remaining from the first screening. This sorting eliminated 1034 articles. The remaining 72 articles were examined in detail. A detailed analysis of the full texts allowed the elimination of 45 papers; thus, 27 articles remained. Finally, one-step backward snowballing (Jalali & Wohlin, 2012) was performed on the remaining 27 papers. To achieve this, a systematic hand search was conducted on the reference lists of the final set of selected articles to identify additional relevant articles that had not been uncovered through previous search strategies. This search allowed for the incorporation of three supplementary publications (Paunović et al., 2022; Rathod et al., 2018). Finally, the set of analyzed papers that matched all the inclusion criteria amounted to 30 articles published in 26 different peer-reviewed journals. This number is comparable to the number of selected articles in several other literature reviews in different research fields (e.g., Elueze (2016): Translation in agriculture (27 articles); Ratajczak & Szutowski (2016): CSR and innovation (24 articles); Cloutier & Amara (2023): Innovation cooperation for manufacturing SMEs (29 articles)). The flow diagram in Fig. 1 summarizes the successive electronic and manual iterations, leading to the final selected set of articles for analysis.

Stages 3 and 4: synthesis and analysisAll 30 selected articles were managed using computer-based methods following the approach outlined by Petticrew (2006). For this study, a Microsoft Excel database was developed to effectively summarize key information from each article. This database included the details, such as the article's reference, explicit definitions of knowledge transfer and its determinants, channels used by researchers to disseminate their research findings, unit of analysis considered, methodological approach utilized, analytical techniques applied, geographical context of the study, and other relevant data. The database served as a valuable tool for organizing and synthesizing the collected information, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the findings from the selected articles.

The results of the synthesis and analysis of the research material corresponding to the last two steps of the SALSA method, are described in detail in the Results section. First, the general features of the included studies are presented. Subsequently, the analytical findings from the selected studies are discussed, enabling 1) edifying an integrative conceptual framework linking agricultural knowledge transfer with its levers and barriers, and 2) proposing a research agenda that highlights the most promising opportunities for future research.

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the selected studiesDistribution of the articles by publication outletTable 3 shows the distribution of the 30 articles selected from the 26 journals. The Journal of Agricultural Education & Extension, Journal of Agricultural & Food Information and the American Journal of Human Ecology each have two articles. All the other journals have only one article each. The third of the articles (10 out of 30 articles) were published in journals belonging to the first and second quartiles (Q1 and Q2), according to the journal impact factor ranking of the Web of Science Journal of Citation Report (e.g., Technovation; Biological Conservation; Ecological Economics; Technological Forecasting & Social Change; Journal of Agricultural Education & Extension). The list of journals identified from the SLR reveals a diverse array of publications covering several fields relevant to our research. This broad disciplinary spectrum results in a fragmented research landscape as studies span multiple domains, leading to a more dispersed body of work.

Distribution of the retained articles according to the journals (editorial trend).

| NAME OF THE JOURNAL | NUMBER OF ARTICLES | CATEGORY |

|---|---|---|

| 1. JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION & EXTENSION | 2 |

|

| 2. JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL & FOOD INFORMATION | 2 |

|

| 3. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN ECOLOGY | 2 |

|

| 4. AFRICAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH | 2 |

|

| 5. AFRICA EDUCATION REVIEW | 1 |

|

| 6. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION | 1 |

|

| 7. ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS | 1 |

|

| 8. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY | 1 |

|

| 9. JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION | 1 |

|

| 10. JOURNAL OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT | 1 |

|

| 11. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INTEGRATIVE AGRICULTURE | 1 |

|

| 12. PLOS ONE | 1 |

|

| 13. PROFESSIONAL GEOGRAPHER | 1 |

|

| 14. SCIENCE AND PUBLIC POLICY | 1 |

|

| 15. TECHNOLOGICAL FORECASTING AND SOCIAL CHANGE | 1 |

|

| 16. TECHNOVATION | 1 |

|

| 17. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT | 1 |

|

| 18. BULGARIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE | 1 |

|

| 19. SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL OF APPLIED SOCIAL AND CLINICAL SCIENCE | 1 |

|

| 20. ANTHROPOLOGICAL NOTEBOOKS | 1 |

|

| 21. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT | 1 |

|

| 22. INDIAN JOURNAL OF EXTENSION EDUCATION | 1 |

|

| 23. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED RESEARCH | 1 |

|

| 24. TROPICAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH | 1 |

|

| 25. THE INTERNATIONAL INFORMATION & LIBRARY REVIEW | 1 |

|

| 26. QUALITY INNOVATION PROSPERITY | 1 |

|

Overall, the trend shows a growing interest in transferring agricultural research to farmers over the past few decades, with a notable increase in recent years (Fig. 2). The findings showed that the number of publications related to the transfer of agricultural research to farmers increased significantly between 2013 and 2024. In 2013, there was a slight increase with three publications, followed by a significant increase in 2015, with five publications. Between 2016 and 2018, the number of publications stabilized slightly, with two publications each year, suggesting sustained interest but at a moderate pace. Between 2016 and 2021, publications continued at a steady pace, with two publications each year from 2016 to 2018, and one publication each year from 2019 to 2021. There was a marked increase between 2022 and 2023, with four publications in 2022 and two in 2023. Publications were sporadic from 1995 to 2012, with only one publication each in six years of this period, indicating perhaps a reduction in priority for the topic of transferring agricultural research to farmers. However, most of the articles (24 of 30) were published in the last decade, suggesting a clear gain in prominence for the topic in agricultural science research, particularly after 2012.

The distribution of articles by contry reflects the country being studied in the article rather than the author(s)’ country of origin. This distribution shows that almost all (28) used data collected from only one country. The only two exceptions are Maas et al. (2021), which focused on Germany and Austria, and David et al. (2010), which examined India and Ethiopia. The most studied country is Nigeria, with 5 of the 30 articles, representing 16.67 % of the total (Faborodee & Ajayi, 2015; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Ifeanyieze et al., 2017; Mgbenka et al., 2013; Okocha, 1995). Ethiopia and Iran followed with four (13.33 %) articles each (Ethiopia – Ayalew & Abebe, 2018; Bayissa, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Iran – Ahmadinejad, 2020; Ansari et al., 2016; Karamidehkordi, 2013; Taheri et al., 2022). The United States follows with three, accounting for 10 % of the total (Duram & Larson, 2001; Getson et al., 2022; Larson & Duram, 2000). Twelve countries, Spain, South Africa, Colombia, India, Russia, Australia, Bulgaria, Indonesia, Mozambique, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Sri Lanka, were represented by one article each.

When considering the distribution of selected studies in major world regions, Africa had the highest proportion (37 %). Asia followed with 23 %, Europe 16.67 %, North America (USA) 10 %, South America 3.33 %, and other continents, 3.33 %. Studies involving multiple continents accounted for 6.67 % of the total (see Fig. A.1 in Appendix A).

Publication trends by unit of analysis and fields studiedThe distribution of articles according to the unit of analysis shows a focus on multi-unit studies, encompassing agricultural researchers and other stakeholders (refer to Fig. A.2 in Appendix A). These studies represent 46 %, or 14 of 30 articles (e.g., Ansari et al., 2016; Karamidehkordi, 2013; Simbe, 2022; Taheri et al., 2022; Wheeler, 2008). Following closely are studies focusing specifically on agricultural researchers, with 40 %, or 12 of 30 articles (e.g., Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Larson & Duram, 2000; Maas et al., 2021). Universities, research centers, and research institutes each account for 7 %, or 2 of 30 articles each (e.g., Dirimanova & Radev, 2017; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012; Thurner & Zaichenko, 2018).

The distribution of articles in the field of application indicates that general agriculture is by far the most studied field, accounting for 67 % of the articles (20 of 30) (e.g., Ahmadinejad, 2020; Ansari et al., 2016; Okocha, 1995). This was followed by sustainable agriculture, representing 13 % (4) (e.g., Larson & Duram, 2000; Maas et al., 2021). Less frequently covered fields include agricultural innovation and the combination of fish farming and coffee production, each accounting for 7 %, or two articles (e.g., Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012), and rural and organic agriculture, represented by one each (e.g., Wheeler, 2008) (refer to Fig. A.3 in Appendix A).

Distribution of articles by methodological approach and data collection techniqueThe most used methodology is quantitative, appearing in 47 % of the articles (14) (e.g., Cruz et al., 2022; Getson et al., 2022). This is followed by qualitative methodology, used in 13 articles, or 43 % (e.g., Ansari et al., 2016; Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Hočevar & Istenič, 2014; Karamidehkordi, 2013). This distribution reveals a nearly split between the quantitative and qualitative methodologies, indicating that both types of analysis were valued almost equally. Mixed methods, which combine both quantitative and qualitative approaches, were used in the remaining three (10 %) (e.g., Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023) (refer to Fig. A.4 in Appendix A).

Table 4 details the various analytical techniques utilized in the selected articles. Content analysis is the most prevalent, featuring in 30 % of the articles (e.g., Ansari et al., 2016; Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Hočevar & Istenič, 2014). Multivariate regression techniques account for 16.7 % of the articles, with specific techniques under this category including structural equation modeling (Ahmadinejad, 2020; Taheri et al., 2022), logistic regression (Thurner & Zaichenko, 2018), and ordered probit regression (Wheeler, 2008). Multi-quantitative methods (e.g., Duram & Larson, 2001; Maas et al., 2021) and inferential statistics (e.g., Kaur & Kaur, 2013; Mgbenka et al., 2013) each were used in 13.3 % of the articles. Qualitative-quantitative methods appear in 10 % of the articles (e.g., Okocha, 1995). Case studies (e.g., Karamidehkordi, 2013), action research (e.g., Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012), multi-qualitative methods (e.g., Dharmawan et al., 2023), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Cruz et al., 2022) were less commonly used.

Distribution of analytical techniques in the selected articles.

| ANALYSIS TECHNIQUE | NUMBER OF ARTICLES | PROPORTION OF ARTICLES |

|---|---|---|

| Content analysis | 9 | 30 % |

| Multivariate regression | 4 | 16.7 % |

| 2 | 50 % |

| 1 | 25 % |

| 1 | 25 % |

| Multi-quantitative methods | 5 | 13.3 % |

| Qualitative-quantitative methods | 3 | 10 % |

| Inferential statistics | 4 | 13.3 % |

| Case studies | 2 | 6.7 % |

| Research action | 1 | 3.3 % |

| Multi-qualitative methods | 1 | 3.3 % |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | 1 | 3.3 % |

| Total | 30 | 100 % |

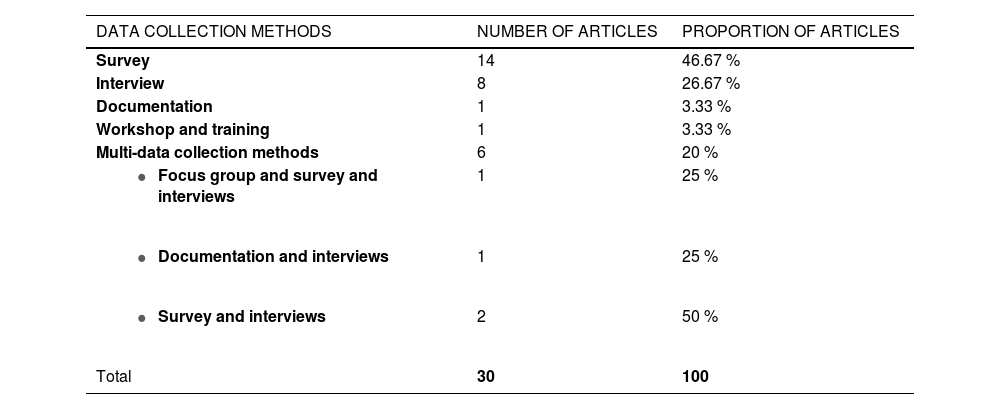

Table 5 presents the distribution of articles based on data collection methods. Fourteen articles (46.67 %) used surveys (e.g., Ayalew & Abebe, 2018; Maas et al., 2021; Taheri et al., 2022; Wijerathna et al., 2015), followed by multiple data collection methods (6 or 20 %,) (e.g., Ifeanyi-Obi & Asuquo, 2023; Karamidehkordi, 2013). Interviews (e.g., Ansari et al., 2016; Bayissa, 2015a; Dharmawan et al., 2023) were used in eight (26.67 %), whereas documentation methods (e.g., Jarábková, 2019) and workshops and training (e.g., Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012) were the least common, each accounting for 3.33 % (one article).

Distribution of articles by data collection technique.

| DATA COLLECTION METHODS | NUMBER OF ARTICLES | PROPORTION OF ARTICLES |

|---|---|---|

| Survey | 14 | 46.67 % |

| Interview | 8 | 26.67 % |

| Documentation | 1 | 3.33 % |

| Workshop and training | 1 | 3.33 % |

| Multi-data collection methods | 6 | 20 % |

| 1 | 25 % |

| 1 | 25 % |

| 2 | 50 % |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Through the synthesis of 30 articles in the SLR, various definitions associated with the concept of knowledge transfer in the agricultural field were discerned (Table 6), which can be approached from three perspectives. 1) Definitions that perceive knowledge transfer as a sequential process: this perspective views knowledge transfer as a process that enables knowledge production by scientific researchers and its subsequent application in the agricultural sector and is closely aligned with the knowledge-driven model, also known as the “science push model” (Dilling & Lemos, 2011; Landry et al., 2001; Weiss, 1979). These definitions underscore the importance of ensuring that research outcomes reach farmers and agricultural practitioners. 2) Definitions that highlight the interactive aspects of the knowledge transfer process: from this perspective, knowledge transfer is an interactive process involving multiple stakeholders, including researchers, farmers, extension workers, policymakers, and other relevant actors within the agricultural ecosystem. It aligns with the “interactive model,” which recognizes the non-linear, collaborative and dynamic nature of knowledge transfer process (Landry et al., 2001). 3) Definitions that consider knowledge transfer as a problem-solving mechanism for practical solutions and real-world benefits: this perspective considers knowledge transfer as a mechanism for addressing specific challenges in the agricultural sector and ensuring that scientific advancements translate into tangible socioeconomic benefits. This aligns with the “problem-solving model,” also known as the “demand-pull model” (Landry et al., 2001; Weiss, 1979; Yin & Moore, 1988). The transfer of agricultural research is guided by the identification and prioritization of problem-oriented research that directly responds to the needs and problems faced by the agricultural community.

Conceptual definitions of knowledge transfer within the selected studies.

| CONCEPTUAL DEFINITION OF KNOWLEDGETRANSFER IN AGRICULTURE | AUTHORS FROM SELECTED ARTICLES | PURPOSE |

|---|---|---|

| DEFINITIONS THAT PERCEIVE KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER AS A SEQUENTIAL PROCESS | ||

| Research uptake activities involve all activities aimed at communicating research findings to the target audience to ensure that the target audience utilizes the research outcomes. | Ifeanyi-obi and Asuquo (2023, p. 16). | Definitions that perceive knowledge transfer as a process enabling the production of knowledge by scientific researchers and its application within the agriculture. |

| Technology transfer is the main component of technology development. This is because, for the developed technology to be applied effectively, it needs to reach the end users of the technology with its full package. The feedback needs to reach the developer of the technology as well to involve all actors in the decision-making. | Ayalew & Abebe (2018, p. 683). | |

| Technology transfer is a critical process in transforming agricultural research innovations into applications for end users. It helps to improve economic growth, transform lives and boost outputs. | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| Research uptake includes all actions that aid and contribute to the use of research evidence by policymakers, practitioners and other development actors. It is aimed at stimulating end users of agricultural research findings, including policymakers, agricultural practitioners, researchers, and/or implementers, into growing aware of and accessing and applying research knowledge/findings/output in agricultural policy and practice. | Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023, p. 16). | |

| Commercialization of knowledge is a process that transforms the knowledge generated into marketable products (Yadollahi Farsi and Kalathaie, 2012). It begins when a business is created as a way to use modern scientific and technological advancements, with the aim of responding to market demands through design, development, manufacturing, marketing, and subsequent efforts to improve the product (Mehta, 2008). | Ahmadinejad (2020, p. 150). | |

| Davenport and Prusak (1998) argue that knowledge transfer involves two actions, namely, transmission (the process of sending knowledge to a potential recipient) and absorption (by the recipient – person/ institution). | Fongwa & Marais (2016, p. 193). | |

| Technology transfer includes direct or indirect transmission of scientific knowledge to real life (Brennenraedts, Bekkers and Verspagen, 2006). | Jarábková et al. (2019, p. 138). | |

| Technology transfer refers to deliberate, goal-oriented relationship between two or more persons, groups, or organizations who exchange technological knowledge (Autio and Laamanen, 1995). | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| Technology transfer refers to movement of ideas, inventions and prototypes within companies, from research producers to a wide group of users including government departments, non-profits, industries and universities (Harman and Harman, 2004). | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| Stock and Tatikonda (2000) described technology transfer as the act of conveying and utilizing technological innovation by the recipient to achieve set objectives, within cost and time targets. Technology transfer is, therefore, the movement of relevant specialized knowledge or innovations from research institutes to farmers for adoption with the help of extension agents and providing feedback to researchers to achieve the intended objectives. | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| DEFINITIONS THAT HIGHLIGHT THE INTERACTIVE ASPECT OF THEKNOWLEDGE TRANSFER PROCESS | ||

| REFILS (Research-Extension-Farmer-Input Linkage System) provides a means of sharing information at the point of overlapping between its different actors through the use of various activities. | Faborode & Ajay (2015, p. 82). | Definitions that highlight the interactive aspect of knowledge transfer. |

| For effective transfer of technology, strong inter-organizational linkage is vital because of the involvement of various organizations in the process (Sen, 1984). | Kaur & Kaur (2013, p. 699). | |

| Technology transfer requires research stations to disseminate information through extension agents and others to ensure that target audience receive the innovation through media and other means. | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| The rate at which technology transfer is accepted for adoption depends on the effectiveness of the linkages. | Ifeanyieze et al. (2017, p. 2064). | |

| DEFINITIONS THAT CONSIDER KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER AS A PROBLEM-SOLVING MECHANISM FOR PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS AND REAL-WORLD BENEFITS | ||

| Technology transfer holds a great potential for promoting innovation and competitiveness at regional and national levels (Bennett and Vaidya, 2005). | Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012, p. 1). | Definitions that consider knowledge transfer as a corrective action. |

| Effective dissemination of information on sustainable agriculture is one way to encourage widespread adoption of sustainable farming systems. | Larson & Duram (2000, p. 173). | |

| The outreach, or extension, tasks refer to the more direct contribution of higher education in agriculture to agricultural and rural development. It may include educational programs for communities beyond the university campus, conducting policy, industry and community-oriented research on issues identified by the consumers, and offering various kinds of services to the community such as technical assistance and agricultural and rural planning (Van den Bor et al., 1989). | Wijerathna et al. (2015, p. 286). | |

The SLR revealed that a majority of the articles (20, or 66.66 %) did not explicitly draw upon theoretical foundations to study knowledge transfer in the agricultural sector. The lack of a unified framework has likely led to a fragmented approach to the study of knowledge transfer, resulting in a plethora of perspectives that struggle to provide a comprehensive understanding of the process within the agricultural context. Table 7 provides a comprehensive overview of the distinct theoretical perspectives identified in this SLR and corresponding articles. These theories include the diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory, information behavior theory, technology acceptance model (TAM), theory of planned behavior (TPB), situated learning or communities of practice (CoPs) theory, the adoption-diffusion model of innovation, Nonaka's knowledge creation theory, and the model of public engagement.

Principal theoretical frameworks adopted in knowledge transfer studies involving agriculture.

| Theoretical perspectives | Foundational authors of these theoretical perspectives | Conceptual overview | Examples of articles of the SLR that discussed these theoretical perspectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion of innovations theory/Adoption-diffusion model of innovation | Rogers (1962) | The diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory, developed by Rogers (1962), explores the process by which innovations, technologies and ideas spread within a community. He also identified five categories of adopters (based on their willingness and speed to adopt innovations): innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Additionally, the DOI theory highlights five key attributes of innovations that influence the rate of adoption: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability (Rogers, 2003). | Larson & Duram (2000)Duram & Larson (2001) |

| Information behavior theories:•Cost-Benefit Model.•Least-Effort Model. | Hardy (1982)Zipf (1949) | The cost-benefit model and the least-effort model, proposed by Hardy in 1982 and drawing on Zipf's Law of Least Effort from 1949, are two influential theories in information-seeking behavior that help to explain how individuals choose information sources. The first model suggests that individuals evaluate the expected benefits of obtaining information against the potential cost. Information-seekers are more likely to choose sources that offer the greatest benefits, even if accessing these sources requires more effort. The second suggests that individuals tend to minimize the effort needed to obtain information, even at the expense of information quality, presenting a different approach to understanding information-seeking behavior. | Okocha (1995) |

| Technology acceptance model (TAM) | Davis (1989) | The TAM, proposed by Davis in 1989, offers a framework for understanding user acceptance and utilization of technology. It suggests that the intention to use a technology is primarily influenced by perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. | Taheri et al. (2022) |

| Theory of planned behavior (TPB) | Ajzen (1988)Ajzen (1991)Ajzen (2011) | The TPB, developed by Ajzen in the late 1980s, is a psychological framework that seeks to explain human behavior through three core components: attitudes, social aspect (or subjective norms), and perceived behavioral control. | Wijerathna et al. (2015) |

| Situated learning or communities of practice (CoPs) theory | Lave & Wenger (1991)Lave (1988)Wenger (1998) | Situated learning (SL) is a theoretical framework that redefines learning as a social process that is intricately tied to its social context. At its core are the communities of practice (CoP), which refers to groups of individuals (in the same field of expertise or professional practice) united by a shared interest or passion, who engage in collective and collaborative learning and continued refinement of expertise through collaborative interactions and shared experiences (Wenger, 1998; Wenger et al., 2002). Wenger (1998) analyzes CoPs through practice (learning by doing); community (learning by belonging); meaning (learning by experience); and identity (learning by becoming). | Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012) |

| Nonaka's knowledge creation theory | Nonaka (1994)Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) | Nonaka's theory of knowledge creation, often referred to as the SECI model, is a seminal framework in the field of knowledge management. It emphasizes that knowledge is created through a continuous and dynamic interaction between two types of knowledge: tacit and explicit. The model involves four sequential modes of knowledge conversion: 1) socialization, 2) externalization, 3) combination, and 4) internalization, before returning once more to socialization. This spiral process, where each mode builds on the previous one, implies that knowledge creation is implicitly knowledge accumulation (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). | Simbe (2022) |

| Public Engagement Model (PEM) | The PEM posits that scientific communication should be a bidirectional and interactive process, as opposed to a unidirectional transfer of information from scientists to the public. It recognizes the significant influence of social and psychological factors on the public's reception and interpretation of scientific information. | Getson et al. (2022) | |

| Triple Helix theory/Mode 1 and Mode 2 Knowledge Production | Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (1995)Gibbons et al. (1994) | The Triple Helix theory, developed by Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff in the mid-1990s, explores the dynamic relationship between three key actors: universities, industries, and governments.Mode 1 and Mode 2 knowledge production concepts were introduced by Gibbons et al. (1994). Mode 1 research has a focus on new knowledge as defined by a set of peers within a particular discipline, whereas Mode 2 research focuses on new modes of academic activities that are cross disciplinary, outward-facing, and concerned with the problems of the milieu of practice. | Hočevar & Istenič (2014)Fongwa & Marais (2016) |

From the overview of the main theories utilized, one notices that some important theories in knowledge transfer and uptake literature have not been considered. To address this gap, three additional theoretical frameworks are suggested: resource-based view theory (RBV), neoinstitutional theory, and motivation theory. These theoretical frameworks, widely used to address knowledge transfer in other research fields (health, business, social sciences, engineering, etc.), are particularly relevant for addressing the persistent gap between the scientific research and agricultural communities. Table 8 highlights the theoretical foundations, main contributions, and analytical levels of these three theories.

Other relevant theoretical perspectives.

| Resource-based view | Neo-institutional theory | Motivation theory | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main authors | Barney, 1991; Conner & Prahalad, 1996; Grant, 1996; Kogut & Zander, 1992. | DiMaggio & Powel, 1983;Scott, 1987; Zucker, 1977. | Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Gagné & Deci, 2005. |

| Theoretical foundations | The resource-based view (RBV) theory helps to understand the knowledge transfer process. It focuses on the relationship between internal resources, profitability, and ability of an organization to provide a sustainable competitive advantage. | This theory focuses on the institutional environment in which organizations operate. It posits that a set of values, norms, and organizational models exist outside organizations, which influence their structures and management methods (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). | According to the theory of self-determination (SDT), motivation exists along a continuum of self-determination and can be categorized into three main types: amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation. |

| Contributions | This theory assumes that researchers are like entrepreneurs in private companies, using many resources deployed and coordinated in the process of publishing, transferring, and commercializing research findings. As a result, researchers have access to tangible and intangible resources that differ from one researcher to another, generating heterogeneity (Landry et al., 2010; Amara et al., 2015). Such a perspective suggests that the probability of publishing and transferring the research findings to the practice milieu increases when resources are coordinated and managed appropriately. | The theory outlines three types of institutional pressures (Engwall, 2007): 1. Coercive pressures, which refer to both formal pressures (exerted by external entities such as the state, funding organizations, dedicated organizations, and government agencies) and informal pressures (practices and habits); 2. Normative pressure arising from actors outside the research institution, such as non-governmental organizations or professional associations, who establish norms, values, and expectations related to knowledge transfer; 3. Mimetic pressure arising from the imitation of performance-related standards in an uncertain context. | The self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 1985) provides a useful framework for understanding individual motivation to undertake certain activities. It “focuses on types, rather than just amount, of motivation, paying particular attention to autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and amotivation as predictors of performance, relational, and well-being outcomes” (Deci & Ryan, 2008, p. 182). |

| Analysis level | Organizational | Institutional | Individual |

The SLR of the 30 selected articles identified 19 different channels of knowledge transfer utilized by agricultural researchers to reach farmers. However, no conceptual categorization of these channels has been done. Following Jbilou (2010), the channels of knowledge transfer identified in this SLR are classified into two dimensions: the type of medium of the transfer and the form of the transfer. The former can be interactive oral, text-based, electronic, or structural media. The latter could be didactic (Estabrooks et al., 2008; Madsen, 2009), dialogic (Beech et al., 2010; Jones, 2000; Schmidt & Stadermann, 2023), tactical (Blumenthal & Thier, 2003; Liew et al., 2012; Newton et al., 2007), practical (Oermann et al., 2008), thematic (Estabrooks et al., 2008), electronic (Mairs et al., 2013), or strategic (Liew et al., 2012; Perkmann & Walsh, 2008). As advocated by Jbilou (2010, p. 94), the didactic form involves an interactive oral medium based on the demonstration of how to effectively use research findings, as well as a discussion with users of the implications of using these findings. The research results are thus presented in the context of teaching thanks to practical training courses, workshops, seminars, and conferences targeting practitioners. Similarly, the dialogic form also involves an interactive oral medium based on discussion and mutual exchange of the practical implications of the research findings and the conditions of their implementation. “During this exchange, both the researcher and the user are experts. One is an expert on the research result and its use, the other is an expert on the implementation environment and its contingencies” (Jbilou, 2010, p. 95, translated by authors). This form of transfer channel includes discussion groups, partnership platforms, exchange visits, and joint-on field research.

Knowledge transfer channels can also use written media in three different forms: tactical, practical, and thematic. These forms can be considered as strategies designed to achieve a specific objective: the use of research results. Specifically, the tactical form is based on the drafting of illustrated and appealing reports for potential users, whereas the practical form designates a channel of knowledge transfer based on the publication of articles in professional journals, enabling research results to be presented in a practical way that is accessible to practitioners. The thematic form refers to a knowledge transfer channel that draws on the writing of reports on specific themes relevant to target audiences (Jbilou, 2010, p. 95). Knowledge transfer channels can also take forms based on electronic media, such as websites, blogs, online newspapers, and e-newsletters, described in electronic form. Finally, knowledge transfer channels can operate through a structural medium based on a formal contract that may have specific objectives, such as patenting innovations and creating spin-offs, and considered a strategic form of knowledge transfer.

The results of classifying the 19 channels of knowledge transfer identified in this SLR by type of transfer medium and form of transfer are presented in Table 9, which also indicates the formal or informal nature of each channel of transfer. To our knowledge, this original classification is the first taxonomy of channels of knowledge transfer from agricultural research to farmers.

Taxonomy of knowledge transfer channels from agricultural researchers to farmers.

| CATEGORY NAME | DEFINITION | KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER MECHANISM IN AGRICULTURE | EXAMPLES OF AUTHORS FROM SLR | FORMAL TRANSFER MECHANISM | INFORMAL TRANSFER MECHANISM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTERACTIVE ORAL MEDIUM | ||||||

| DIDACTIC FORM | An interactive oral medium based on the demonstration of how to effectively use research findings, as well as discussions with users of the implications of using these findings. | 1. Direct interventions with end-users | ||||

| Faborode and Ajayi (2015)Helen et al. (2010)Karamidehkordi (2013)Larson and Duram (2000)Mgbenka et al. (2013)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012)Wijerathna et al. (2015) | X | ||||

| 2. Group learning | ||||||

| Ahmadinejad (2020)Ansari et al. (2016)Duram and Larson (2001)Hočevar and Istenič (2014)Ifeanyieze et al. (2017)Larson and Duram (2000)Taheri et al. (2022)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012)Thurner & Zaichenko (2018)Wijerathna et al. (2015) | X | ||||

| Dirimanova & Radev (2017)Hočevar & Istenič (2014)Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023) | X | ||||

| Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Kaur & Kaur (2013)Mgbenka et al. (2013) | X | ||||

| 3. Structured educational program | ||||||

| Ayalew and Abebe (2018)Ahmadinejad (2020)Cruz et al. (2022)Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Fongwa and Marais (2016)Getson et al. (2022)Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023)Karamidehkordi (2013)Kaur & Kaur (2013)Simbe (2022)Taheri et al. (2022) | X | ||||

| 4. Exhibitions and agricultural shows | ||||||

| Ahmadinejad (2020)Kaur & Kaur (2013)Dirimanova & Radev (2017) | X | ||||

| 5. On-Farm research initiatives | ||||||

| Karamidehkordi (2013)Kaur & Kaur (2013)Mgbenka et al. (2013) | X | ||||

| DIALOGIC FORM | An interactive oral medium based on discussion and mutual exchange mechanisms of the practical implications of the research findings and the conditions of their implementation. | 6. Participatory activities | ||||

| Ahmadinejad (2020)Cruz et al. (2022)Karamidehkordi (2013) | X | ||||

| 7. Group meetings | ||||||

| Dharmawan et al. (2023)Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012) | X | ||||

| 8. Forums | ||||||

| • Experience sharing forums / Interaction forums / Feedback systems | Ayalew & Abebe (2018)Bayissa (2015a)Dirimanova & Radev (2017)Helen et al. (2010) | X | ||||

| 9. One-on-One communication | ||||||

| Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Ayalew & Abebe (2018)Simbe (2022)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012) | X | ||||

| TEXT-BASED MEDIUM | ||||||

| THEMATIC FORM | A written medium drawing on the writing of reports on specific themes relevant for targeted audiences. | 10. Academic and scientific publications | ||||

| Ayalew & Abebe (2018)Dharmawan et al. (2023)Duram & Larson (2001)Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023)Larson & Duram (2000)Okocha (1995)Thurner & Zaichenko (2018) | X | ||||

| 11. Informational materials | ||||||

| Ayalew & Abebe (2018)Dharmawan et al. (2023)Duram & Larson (2001)Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Hočevar & Istenič (2014)Ifeanyieze et al. (2017)Larson & Duram (2000) | X | ||||

| TACTICAL FORM | A written medium based on the publication of articles in professional journals, enabling research results to be presented in a practical way and accessible to practitioners.(Illustrated report) | 12. Technical and extension publications | ||||

| Karamidehkordi (2013)Okocha (1995) | X | ||||

| PRACTICAL FORM | A written medium focused on the direct application and demonstration of research findings. | 13. Policy reports | ||||

| Ifeanyi-obi and Asuquo (2023) | X | ||||

| ELECTRONIC MEDIUM | ||||||

| ELECTRONIC FORM | A digital representation or format of information or communication. | 14. Online communication platforms | ||||

| Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Hočevar & Istenič (2014)Larson & Duram (2000)Wheeler (2008) | X | ||||

| Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023)Wheeler (2008) | X | ||||

| Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023) | X | ||||

| 15. Mass media and digital platforms | ||||||

| Faborode & Ajayi (2015)Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023)Ifeanyieze et al. (2017) | X | ||||

| Kaur & Kaur (2013)Simbe (2022)Taheri et al. (2022) | X | ||||

| STRUCTURAL MEDIUM | ||||||

| STRATEGIC FORM | A structural medium based on a formal contract with specific objectives (involves formal agreements and institutional structures to facilitate knowledge transfer). | 16. Extension and advisory services | ||||

| Bayissa (2015a)Helen et al. (2010)Hočevar & Istenič (2014)Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023)Okocha (1995)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012)Wheeler (2008) | X | ||||

| 17. Technology transfer structures and project development | ||||||

| Thurner & Zaichenko (2018) | X | ||||

| Ansari et al. (2016) | X | ||||

| Ansari et al. (2016) | X | ||||

| Ahmadinejad (2020)Jarábková et al. (2019)Kaur & Kaur (2013) | X | ||||

| Ansari et al. (2016)Thurner & Zaichenko (2018) | X | ||||

| 18. Consulting services | ||||||

| Ahmadinejad (2020)Ansari et al. (2016)Wijerathna et al. (2015) | X | ||||

| 19. Collaborative partnerships | ||||||

| Taheri et al. (2022)Theodorakopoulos et al. (2012)Wijerathna et al. (2015) | X | ||||

| Hočevar and Istenič (2014)Ifeanyieze et al. (2017)Karamidehkordi (2013)Wijerathna et al. (2015) | X | ||||

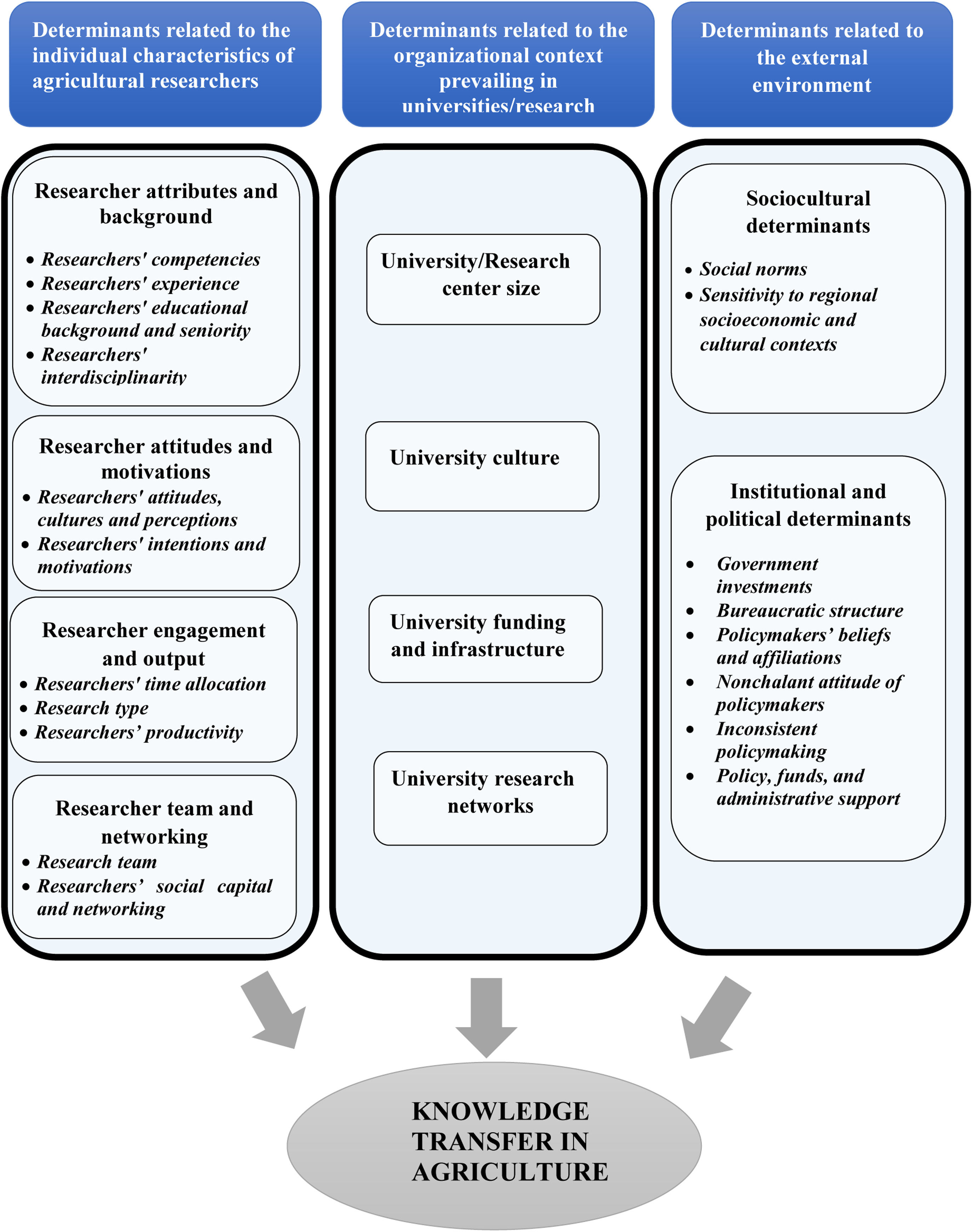

A key objective of this study is to gain a better understanding of the determinants of knowledge transfer from agricultural researchers to the agricultural community. These determinants were systematically classified into three principal categories: 1) determinants related to the individual characteristics of agricultural researchers, 2) those related to the organizational context prevailing in universities and research centers, and 3) those related to the external environment.

Determinants related to the individual characteristics of agricultural researchersThrough this SLR, four key subcategories of determinants related to the individual attributes of agricultural researchers were identified: 1) researcher attributes and background, encompassing researchers’ competencies, educational background, seniority, experience, and interdisciplinarity; 2) researcher attitudes and motivations, including their attitudes, cultural perspectives, perceptions, intentions, and motivations; 3) researcher engagement and output, which refer to their time allocation, productivity, and type of research; and 4) research teams and networking, covering research teams as well as researchers’ social capital and networking abilities (see Table B.1 in Appendix B for a detailed classification).

- a.

Researcher attributes and background

Researchers’ competencies

The competencies and skills of agricultural researchers in terms of transferring knowledge are key drivers for the successful dissemination of scientific research within the agricultural community (e.g., Ansari et al., 2016; Bayissa, 2015a; Getson et al., 2022; Helen et al., 2010; Ifeanyi-Obi, 2023; Karamidehkordi, 2013). These competencies encompass their ability to effectively and skillfully communicate their findings, insights, and innovations to farmers in clear, relevant, meaningful, and useful ways. The ability to convey complex scientific research in an understandable and relevant manner to farmers is innate; researchers may not possess the skills required for effective knowledge transfer. When researchers lack the necessary practical knowledge and skills, they may struggle to conduct demand-driven research that addresses real-world agricultural issues (Bayissa, 2015a). Therefore, without training, knowledge transfer is likely to be less impactful and more challenging to accomplish (Ansari et al., 2016). Through such training, researchers can refine their ability to translate tacit and complex scientific findings into languages and formats that resonate with farmers, making research more accessible and actionable (Ansari et al., 2016; Getson et al., 2022; Helen et al., 2010; Karamidehkordi, 2013).

Researchers’ experiences

The findings reveal that agricultural researchers’ experience plays a crucial role in enhancing the transfer of scientific research to farmers (e.g., Bayissa, 2015a; Helen et al., 2010; Wheeler, 2008; Wijerathna et al., 2015). Experience in knowledge transfer activities within the agricultural community is a strong predictor of researchers’ future engagement in such activities as they recognize their value and impact (Wijerathna et al., 2015). Moreover, experienced researchers with a background in knowledge transfer activities are better equipped to address practical agricultural issues and formulate solutions aligned with the needs of farming communities (Bayissa, 2015a).

Researchers’ educational background and seniority

The findings reveal that researchers’ educational backgrounds play an important role in shaping their approach to knowledge transfer (e.g., Cruz et al., 2022; Wheeler, 2008). Researchers with advanced tertiary education approach their work with greater analytical rigor and open-mindedness, enabling them to critically assess complex challenges and develop innovative solutions (Cruz et al., 2022). Researchers with broader educational backgrounds may be better prepared to appreciate the practical challenges faced by farmers and other local stakeholders (Wheeler, 2008), fostering more relevant knowledge transfer activities, which researchers are more inclined to adjust to meet farmers’ specific needs and conditions. Moreover, the researchers’ seniority or academic rank significantly influences the intensity and effectiveness of this knowledge transfer. Moving up the academic ladder, they gain greater experience and resources, which enhances their capacity for effective knowledge transfer (Duram & Larson, 2001).

Researchers’ interdisciplinarity

Scientific discipline influences the nature of the knowledge being transferred, thereby shaping the process of transferring agricultural research (e.g., Duram & Larson, 2001; Maas et al., 2021). Furthermore, the agricultural sector faces challenges that require insights from a wide range of disciplines. Interdisciplinarity plays a crucial role in facilitating knowledge transfer from researchers to farmers (Maas et al., 2021). Researchers from different disciplines in the agricultural field have a diverse range of perspectives, allowing them to approach complex challenges from multiple angles. In agriculture, where the challenges are multifaceted, this multidisciplinary approach not only enhances problem-solving abilities, but also promotes a more efficient approach to addressing these issues.

- a.

Researcher attitudes and motivations

Researchers’ attitudes, cultures and perceptions

The SLR finds that the divergent perspectives, cultures, and interests of researchers and farmers can significantly exacerbate challenges in the knowledge transfer process (Ansari et al., 2016; Bayissa, 2015b; Maas et al., 2021). Researchers who often prioritize theoretical frameworks and pursue new scientific results may find themselves at odds with farmers who are more concerned about practical and experience-based solutions. Moreover, researchers’ attitudes towards farmers’ knowledge play a crucial role in the knowledge transfer process (Cruz et al., 2022). Some researchers commonly view farmers’ knowledge as inferior or less valuable than scientific knowledge (Cruz et al., 2022). These prejudices and perceptions of inferiority can lead researchers to undervalue farmers’ practical insights grounded in years of experience and a deep understanding of specific agricultural contexts (Cruz et al., 2022).

Researchers’ intentions and motivations

Researchers’ intentions and readiness to transfer their research results to farmers are essential components that influence the knowledge transfer process (Bayissa, 2015b; Taheri et al., 2022). As advocated by many studies in the SLR, researcher motivation is a critical determinant of the success of knowledge transfer activities (e.g., Ahmadinejad, 2020; Bayissa, 2015b; Faborode & Ajayi, 2015; Helen et al., 2010; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Karamidehkordi, 2013; Wijerathna et al., 2015). Specifically, when researchers are not adequately motivated by their institutions (whether through financial rewards, opportunities for career advancement, material gains, public recognition, or honors), they are less inclined to dedicate the necessary time, resources, and effort to engaging with farmers and other potential agricultural users of their research (Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Okocha, 1995). This challenge is compounded by the meritocratic structure prevalent in universities (Anzivino & Cannito, 2024; Soysal et al., 2024), which often prioritizes specific measurable outputs such as publications, citations, and the acquisition of research grants (Hočevar & Istenič, 2014).

In addition, subjective norms shaped by the perception of approval from colleagues or superiors within an institution can significantly influence a researcher's decision to participate in knowledge-transfer activities (Wijerathna et al., 2015). When researchers believe that their peers and the academic institutions value and support their engagement in knowledge transfer activities, they are more likely to feel motivated to prioritize such activities (Ahmadinejad, 2020; Bayissa, 2015b). Personal satisfaction is a key driver motivating academics to engage in knowledge transfer (Wijerathna et al., 2015). When researchers experience a profound sense of fulfillment from seeing their research output, they are not only more likely to participate in these activities but also more committed to sustaining their involvement over time. Similarly, researchers who approach outreach activities positively and view them as enjoyable and inherently valuable are significantly more likely to participate actively (Wijerathna et al., 2015). By perceiving these activities as opportunities to connect with the practical side, address real-world challenges, and contribute to the advancement of agriculture, this participation is fueled by genuine enthusiasm rather than external pressure.

The findings align with a substantial body of literature highlighting the dual nature of motivation, encompassing both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, in influencing researcher engagement in knowledge transfer. For instance, Lam's (2011) framework provides valuable insights into how different motivational drivers affect a researcher's participation in these activities. According to Lam (2011), researchers’ motivations can be divided into three distinct categories: intrinsic satisfaction, derived from intellectual curiosity (puzzle); financial incentives and economic rewards (gold); and the pursuit of professional recognition, reputation enhancement, and career progression (ribbon). The puzzle motivation is linked to intrinsic motivators, while the gold and ribbon motivations are associated with extrinsic motivators.

- a.

Researcher engagement and output

Researchers’ time allocation

According to several studies, the allocation of time across teaching, research, and dissemination activities plays a pivotal role in determining the effectiveness of knowledge transfer within the agricultural sector (Faborode, 2015; Getson et al., 2022; Larson & Duram, 2000; Wijerathna et al., 2015). Researchers’ ability to effectively transfer knowledge to farmers hinges not only on their expertise but also on the availability of sufficient time to meaningfully engage in these activities (Larson & Duram, 2000). Heavy workloads for researchers, including teaching, research, and administrative duties, may create significant time constraints (Larson & Duram, 2000). The constant pressure to fulfill the expectations associated with these multiple roles often results in the de-prioritization of activities that do not yield immediate academic outputs.

Research type

The effectiveness of knowledge transfer to farmers is significantly influenced by the type of research conducted by agricultural researchers (e.g., Ahmadinejad, 2020; Bayissa, 2015a; Mgbenka et al., 2013; Simbe, 2022). Contemporary agricultural research faces a significant disconnect between the practical needs of farmers and the research priorities of academic institutions (Bayissa, 2015a). This gap arises largely from the type of research, which often tends to be theoretical and disconnected from real-world agricultural challenges (Bayissa, 2015a).

Researchers, driven by a combination of intrinsic motivations and external incentives, tend to focus on producing high-impact publications that often emphasize scientific rigor and novelty over practical relevance (Hočevar & Istenič, 2014). This focus on theoretical contributions, while valuable in advancing scientific understanding, often results in research outputs too abstract to be of immediate use in addressing farmers’ challenges (Bayissa, 2015a; Hočevar & Istenič, 2014). Unlike basic research, applied research is explicitly designed to address practical problems and provide solutions that can be implemented in real-world contexts. However, despite its importance, applied research is frequently undervalued in academia and lacks the recognition and support it deserves (Hočevar & Istenič, 2014). Applied research projects, which may yield immediate and tangible benefits for farmers, are often judged by the same criteria as basic research, despite their different objectives (Hočevar & Istenič, 2014).

Researchers’ productivity

The authors found that researchers’ productivity, often measured by academic publications and citations, is a critical factor in the knowledge-transfer process (e.g., Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023). According to Fongwa and Marais (2016), effective knowledge transfer relies heavily on the researchers’ capacity to produce high-quality research. Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo (2023) highlight the importance of publishing articles as a major activity in the transfer of agricultural research.

- a.

Researcher team and networking

Research team

The size of the research team significantly influences the knowledge transfer process. For instance, Thurner & Zaichenko (2018) highlight the crucial role of staff numbers, particularly within Research and technology organizations, and explain how staff expansions or reductions directly impact the effectiveness of technology transfer activities. When a research team has a large number of members, it benefits from a diverse range of skills, expertise, and backgrounds. A larger team also allows a more efficient distribution of workload, ensuring that the responsibilities associated with knowledge transfer are managed effectively.

Researchers’ social capital and networking

Numerous studies underscore the pivotal role of researchers’ social capital in facilitating knowledge transfer within the agricultural sector (e.g., Ahmadinejad, 2020; Bayissa, 2015b, 2015c; Cruz et al., 2022; Dirimanova & Radev, 2017; Faborode & Ajayi, 2015; Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Kaur & Kaur, 2013; Larson & Duram, 2000). Strong social capital accelerates the transfer of information from agricultural researchers to farmers. When researchers forge strong connections with agricultural extensionists, farmers, policymakers, and other stakeholders, dissemination of scientific findings becomes more efficient (Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Ifeanyi-obi & Asuquo, 2023; Mgbenka et al., 2013). By contrast, poor coordination or limited interaction and communication between researchers and other agricultural stakeholders can be detrimental to the transfer and adoption of research (Bayissa, 2015b; Cruz et al., 2022; Faborode & Ajayi, 2015; Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Mgbenka et al., 2013).

The success of knowledge transfer in agriculture hinges on the establishment of effective communication channels that foster interactions between researchers and farmers (Duram & Larson, 2001; Larson & Duram, 2000; Simbe, 2022). Communication in agricultural research should be adapted to fit the farmers’ context, ensuring it is understandable, unambiguous, contextually relevant, and directly applicable to their needs (Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012). Trust in collaborative networks is a fundamental pillar of success (e.g., Ahmadinejad, 2020; Ansari et al., 2016; Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Jarábková et al., 2019; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2012). For effective knowledge transfer, farmers must know that researchers and their affiliated institutions are committed to transparency and the pursuit of shared benefits.

Determinants related to the organizational context in universities/research centersThe SLR helped identify four determinant subcategories related to the organizational context prevailing in universities and research centers: 1) university/research center size, 2) university culture, 3) university funding and infrastructure, and 4) university research networks.

University/Research center size

The impact of university size on agricultural knowledge transfer was highlighted as a significant factor in some studies. The size of an institution, often quantified by the number of research staff members or the presence of a dedicated knowledge and technology transfer office, can substantially influence the effectiveness of knowledge transfer activities (Thurner & Zaichenko, 2018). Larger universities and research institutions tend to possess more extensive expertise, specialized support structures, greater resources, and a broader knowledge base. These attributes collectively enhance a university's capacity to effectively disseminate agricultural research findings and technologies to the agricultural community.

University culture

Universities’ culture and strategic orientation significantly influence how research is transferred and applied in practical contexts (Fongwa & Marais, 2016; Wijerathna et al., 2015). A university's academic culture, shaped by its values and norms, can facilitate or hinder knowledge transfer to the agricultural community. When a university does not allocate sufficient resources or lacks a clear policy that promotes and supports knowledge transfer activities, it reflects a cultural orientation that may not fully recognize the importance of engagement beyond academic circles (Fongwa & Marais, 2016).