This article examines the nexus between market-sensing capability, knowledge creation, strategic entrepreneurial-orientation and innovation in small and medium sized enterprises (SME). Data was garnered from (n=255) SMEs operating in Jordan and a covariance-based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM) was applied to analyze the data. SEM result illustrates a positive effect of market-sensing capability on (1) knowledge creation, and (2) firm innovation. Knowledge creation process has positive effect on (3) firm innovation. Knowledge creation process (4) mediated the link between market-sensing capability and firm innovation. Strategic entrepreneurial-orientation moderates the link between (5) knowledge creation and firm innovation, such that the positive relationship became weaker when strategic entrepreneurial-orientation is high. Theoretically and empirically this study has contributed to the existing inconsistent findings, and also offer useful managerial insights.

SMEs are responsible for the preponderance of employment in most emerging economies since they make up most of the business in those countries (Lin, 1998). Although, larger firms have material, financial and technological advantages over SMEs (Verhees & Meulenberg, 2004). SMEs are flexible, less bureaucratic, employ informal strategies and decision making is more fluid because private and business objectives are often entwined compared to larger businesses. Aside from these entrepreneurial behavioural advantages and informality, SMEs’ information system is also unique and advantageous. SMEs are purview to direct and indirect, formal and informal, internal and external sources of information which are useful in business operations, innovation, performance and growth (Rosenbusch, Brinckmann, & Bausch, 2011). Effective SMEs are those that pay much attention to innovation (Ireland & Webb, 2007), for the reason that innovation enhances the performance and profit (Keskin, 2006).

The ability to sense and react to the market environment and changes in terms of technology advancement, consumer tastes and demands, innovation and the value offering is called market sensing (Likoum, Shamout, Harazneh & Abubakar, 2018). However, one of the major difficulties facing SMEs is the identification, seizing, stockpiling, mapping, distributing, and creation of knowledge (Sołek-Borowska, 2017). These stages leading up to knowledge creation. Sołek-Borowska (2017) found that knowledge creation is essential for SMEs. She reported that SMEs does what larger businesses are unable to do; which is to use joint-effort, face-to-face communication and cult of owners to create an environment encouraging the creation of knowledge. Competition coupled with consumers’ sophisticated demands, makes it expedient for SMEs to embrace an entrepreneurial orientation so as to remain relevant, enhance performance and in actual fact stay in business (Kraus, Rigtering, Hughes, & Hosman, 2012).

In previous studies, innovation has been reported to occur as a result of the ability to sense the market (Ardyan, 2016), anticipate business environment changes (Fang, Chang, Ou, & Chou, 2014), processes and knowledge management (Quintane, Mitch Casselman, Sebastian Reiche, & Nylund, 2011). Innovation also appears through entrepreneurial orientation (Ardyan, 2016). SMEs have been reported to respond more rapidly and flexibly to intelligence gleaned from the market because making of decision in SMEs is non-bureaucratic (Carson, Cromie, McGowan, & Hill, 1995). This makes enterprises more capable of exploiting the changes in the business and social environment, as well as trends in the market. Because of its disruptive tendencies, firms with weak entrepreneurial orientation will hardly undertake innovative activities. The relationships between innovation strategy, knowledge management and innovation performance is mixed. Moreover, there is a scarcity of theoretical research on how SMEs market-sensing capability leverages the firms’ outcome to achieve innovativeness (Jajja, Kannan, Brah, & Hassan, 2017). This study as a result investigates the inter-relationship and impact of SMEs, market-sensing capabilities, knowledge creation process and strategic orientation on its product/process innovation.

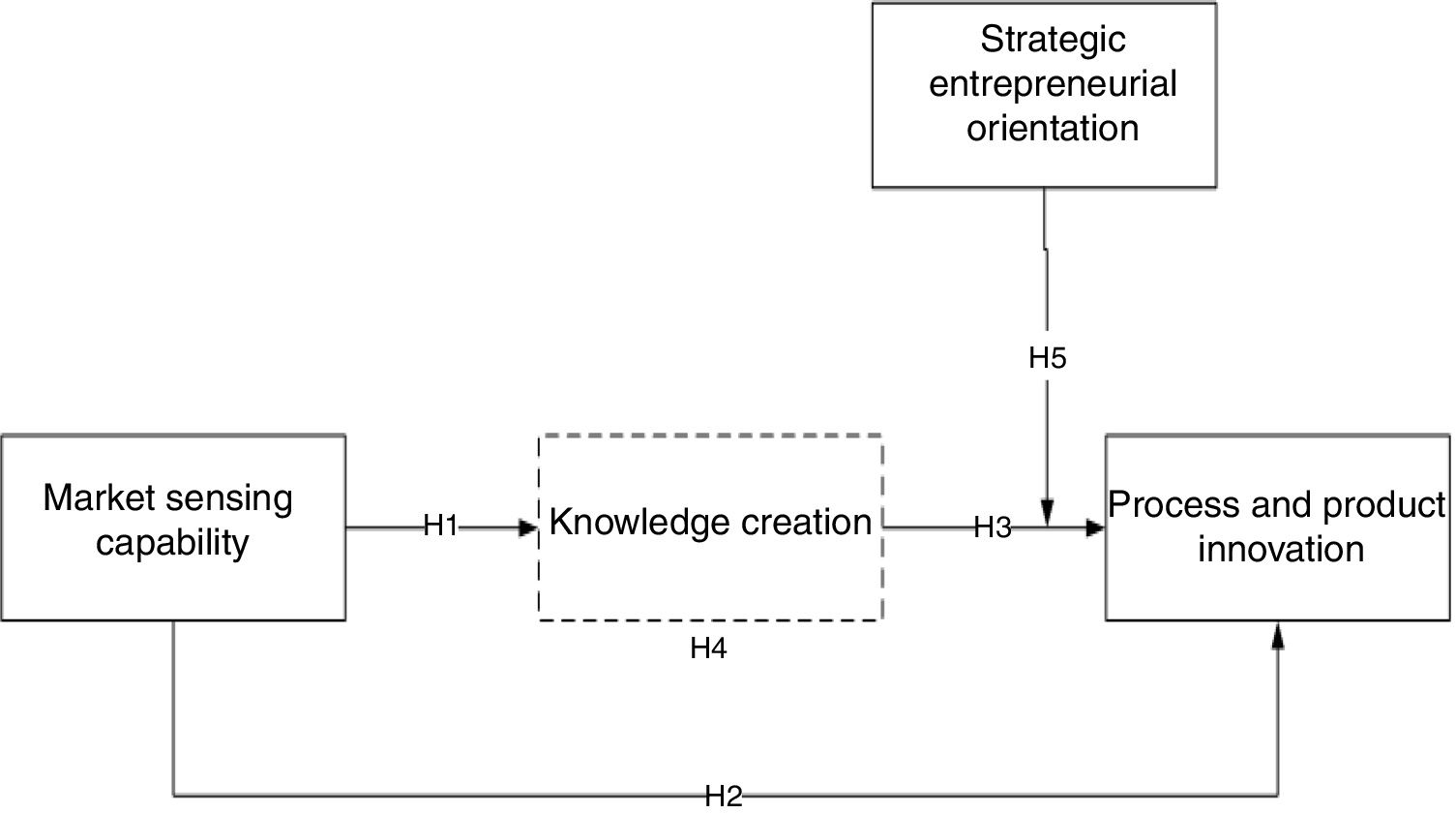

Theoretical background and hypothesesMarket sensing capability and knowledge creationMarket-sensing is “a broad generation of market intelligence by an organization relating to present and future needs of customers, distribution of these knowledge across the organisation's functional unit, and the organization's responsiveness/reaction to the market” (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). Market Sensing is a tool for developing an organization which is skilful at learning, perceiving, and responding to market dynamics (Likoum, Shamout, Harazneh, & Abubakar, 2018). The capability of a firm to assess and apply external knowledge depends on previous related knowledge (Likoum et al., 2018). Thus, previously acquired knowledge infers a capability to identify the worth of new information, integrate it and make use of it commercially (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990a). Research shows that managers emphasized the significance of information regarding customers, competitor, distribution channels, and the larger environs in a venture's target market (Morgan, Zou, Vorhies, & Katsikeas, 2003). Information about firm's customers, competitors, suppliers and other market factors makes up a treasured portion of that firm's knowledge base. Knowledge is fundamental in the search of opportunities (Abubakar, Elrehail, Alatailat, & Elçi, 2017; Nonaka, 2007). market sensing ability can generate high market knowledge, which is speculated to be keen for any active capability (Teece, 2007, 2012). Accordingly, a firm's market sensing capabilities have a positive influence on knowledge creation of firms.H1

Firm market sensing capability has a positive impact on knowledge creation process.

Market-sensing capability, process and product innovationInnovativeness is the development of novel, appropriate, and unique products or services by a firm. It's also a firm openness to embracing new concepts, products, and procedures, consist of the firm's readiness to transform and adopt latest technology and market trends (Rakthin, Calantone, & Wang, 2016). To achieve this, market intelligence is required, since product innovation process can be improved through market knowledge (Luca & Atuahene-Gima, 2007). Sensing ability encourages firm to exert effort in acquiring market facts, operating on varying circumstances to outsmart competitors, creating and sustaining cordial relationships with staffs and customers, and involving inner strengths in conformity with external environments (Desarbo, Di Benedetto, Song, & Sinha, 2005; Likoum et al., 2018). The tendency to procure external market information, or an idea of customer desires, needs, and service procedures, is identified as imperative for new innovation (Johan & Anna, 2018; Rakthin et al., 2016). Thus,H2

Market-sensing capability has a positive impact on process and product innovation.

Knowledge creation, and process and product innovationThe knowledge-based idea of firm explains it as a unique sum of diverse knowledge whose major purpose is to establish, incorporate, and apply knowledge, as well as communicate it within and outside the firm; hence making firm typically “a channel of knowledge flow” (Abubakar et al., 2017; Grant, 1996a). Knowledge is central for assuming technological innovation (Lichtenthaler, 2016). Knowledge is generally considered as a key strategic means to enhance innovation and improve a firm's operation (Alegre, Sengupta, & Lapiedra, 2013; Elrehail, Emeagwali, Alsaad, & Alzghoul, 2018). Mahr, Lievens, and Blazevic (2014) debated that a business qualified for developing knowledge can continually generate the knowledge reserves needed to advance its products and improves its processes. Thus, knowledge base permits a firm to enhance its productivity, cut costs, or upgrade its products, enhances the ability to develop innovative practices, products and services (Shu, Page, Gao, & Jiang, 2012). Similarly, strategic knowledge formation possesses the tendency to reach novelty and process developments (Sankowska, 2013; Quintane et al., 2011). Thus,H3

Knowledge creation has a positive impact on process and product innovation.

Mediating role of knowledge creation processMarket-sensing grants firms’ unique competence, which is the source of creating a viable competitive advantage. Valued competences, like marketing capabilities, cannot be imitated with ease, replaced, or conveyed within rivals; therefore, these capabilities make the base for viable competitive edge (Grant, 1996b). Lankinen and Tuominen (2007) and Olavarrieta and Friedmann (2008) instituted that market-sensing ability is a way of gaining market knowledge for decision-making process. Market sensing abilities promote a firm's tendency to recognize opportunities, improve their customer's experience and knowledge (Reinartz & Kumar, 2000). Businesses can innovate better when current knowledge within the system is employed alongside well internalized knowledge from external sources (Shu et al., 2012). Following the proceeding proposition that a firm's marketing sensing abilities is positively connected to the firm's knowledge creation process, which subsequently has positive influences on the firm's innovativeness. Thus,H4

Knowledge creation process mediates the positive relationship between market-sensing capability and process and product innovation.

Moderating role of strategic entrepreneurial-orientationStrategic entrepreneurial orientation explicitly covers the entrepreneurial phases of firms’ strategies. Lumpkin and Dess (2001) established five scopes of entrepreneurial orientation, which includes; innovativeness; taking the risk; pro-activeness; assertiveness; and autonomy. Entrepreneurial orientation is known as an organizational resource that allows firms to distinguish themselves from their rivals via innovation (Ireland, Hitt, & Sirmon, 2003). Knowledge distribution within a firm turns to knowledge creation and the circulation of knowledge throughout a business firm. The knowledge is then transformed to innovation intended at exploiting market opportunities. Vidic (2013) argued that a relationship exists between entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge formulation. SMEs high with strategic entrepreneurial orientation are also very likely to be highly proactive; displaying a higher predisposition to look for, and seize opportunities in the market (Jantunen, Puumalainen, Saarenketo, & Kyläheiko, 2005). They are likely to be reliant on their knowledge capacity. This is why researcher propose that entrepreneurial orientation firm usually maintain productive learning by finding and exploring value-added opportunities (Chaston & Scott, 2012). Thus,H5

Strategic entrepreneurial-orientation moderates the link between knowledge creation and process and product innovation, such that the impact of knowledge creation on Process and product innovation will be higher when strategic entrepreneurial orientation is higher.

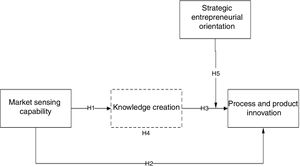

The proposed hypotheses are illustrated diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

MethodResearch measuresMarket sensing capability is the capability to gather and use the information required to commercialize patented innovations from markets. A five items scale was adopted from (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990b; Teece, 2007). Knowledge creation process was captured using 19 items validated by Nonaka, Byosiere, and Konno (1994). Strategic entrepreneurial orientation was captured using nine 5-point Likert-type questions taken from Covin and Slevin (1991) and Lumpkin and Dess (1996) and Jantunen et al. (2005) which investigate the areas of innovativeness, Proactiveness, and risk-taking. Product and process innovation were modelled and captured with 13 items utilized by Škerlavaj, Song, and Lee (2010). All the items were formulated on a 5-point response scale. Where 1 stands for (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree).

Research design and samplingThe developed questionnaire was back-translated to Arabic and to English by translators (Perrewe et al., 2002). About 98% of all firms in Jordan are SMEs. Based on the information obtained from the ministry, 1400 registered SMEs are operating in Amman, Jordan (http://www.jordanyp.com/category/Small_business/city:Amman). Simple random sampling (SRS) are “unbiased and sometimes approximately unbiased estimation of the proportions of people bearing undesirable features in human communities and also total/means of real values of sensitive variables of social interest”. Because everyone has equal chance of being selected and each individual can be sampled. To catapult the accuracy and predict the outcome with high reliability and validity, SRS was adopted and instead of sampling 225 SMEs, the author sampled 300 SMEs. First, several SMES key people were contacted and they agreed to participant in the study. The participants were key representatives of the selected SMEs.

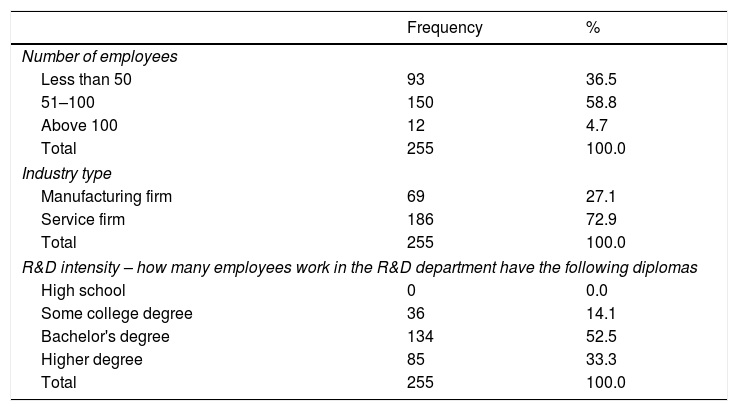

Data analysis and resultsDemographic informationTable 1 presents the demographic features of the Jordanian SMEs investigated.

Demographic data (n=255).

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | ||

| Less than 50 | 93 | 36.5 |

| 51–100 | 150 | 58.8 |

| Above 100 | 12 | 4.7 |

| Total | 255 | 100.0 |

| Industry type | ||

| Manufacturing firm | 69 | 27.1 |

| Service firm | 186 | 72.9 |

| Total | 255 | 100.0 |

| R&D intensity – how many employees work in the R&D department have the following diplomas | ||

| High school | 0 | 0.0 |

| Some college degree | 36 | 14.1 |

| Bachelor's degree | 134 | 52.5 |

| Higher degree | 85 | 33.3 |

| Total | 255 | 100.0 |

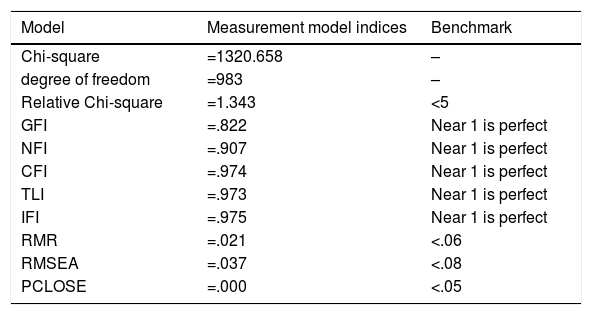

IBM-SPSS AMOS programme v21 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). According to Harrington (2008), “assessing the measurement model validity occurs when the theoretical measurement model is compared with the reality model to see how well the data fits”. Measurement model validity can be determined with a several tools and indicators such as standardized the factor loadings, t-statistics, Chi-square test and popular goodness-of-fit indices namely: Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Bollen's Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Root mean square residual (RMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) etc. The model fit in this study suggest that the dataset fits well with the theoretical factors. See Table 2.

Goodness-of-fit indices.

| Model | Measurement model indices | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | =1320.658 | – |

| degree of freedom | =983 | – |

| Relative Chi-square | =1.343 | <5 |

| GFI | =.822 | Near 1 is perfect |

| NFI | =.907 | Near 1 is perfect |

| CFI | =.974 | Near 1 is perfect |

| TLI | =.973 | Near 1 is perfect |

| IFI | =.975 | Near 1 is perfect |

| RMR | =.021 | <.06 |

| RMSEA | =.037 | <.08 |

| PCLOSE | =.000 | <.05 |

Common method bias (CMB) are biases introduced by instruments; which makes research findings to be contaminated by the ‘noise’ stemming from the biased instruments” (Jahmani, Fadiya, Abubakar, & Elrehail, 2018; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Podsakoff, 2011). The authors proposed stratagem and mathematical approaches, the former includes: ensuring anonymity and confidentiality of the participants and the latter involves series of statistical method applications e.g., Harman single factor test, where scale items are forced to load on a single factor rather than their theoretical factors. Both approaches were utilized in this study.

The menace of non-response bias was assessed by comparing the variables means, then demographics profile of the first 25% responses was compared with the last 25% responses, no significant difference was found (Collier & Bienstock, 2007). Construct validity is defined by convergent validity and divergent validity. Convergent validity is used to corroborate the theoretical correlation claim between items of a construct; and divergent validity is used to corroborate theoretical divergence between items of individual construct and with that of other constructs. To assess convergent and divergent validity, we assess standardized factor loadings (SFL), t-values, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extract (AVE).

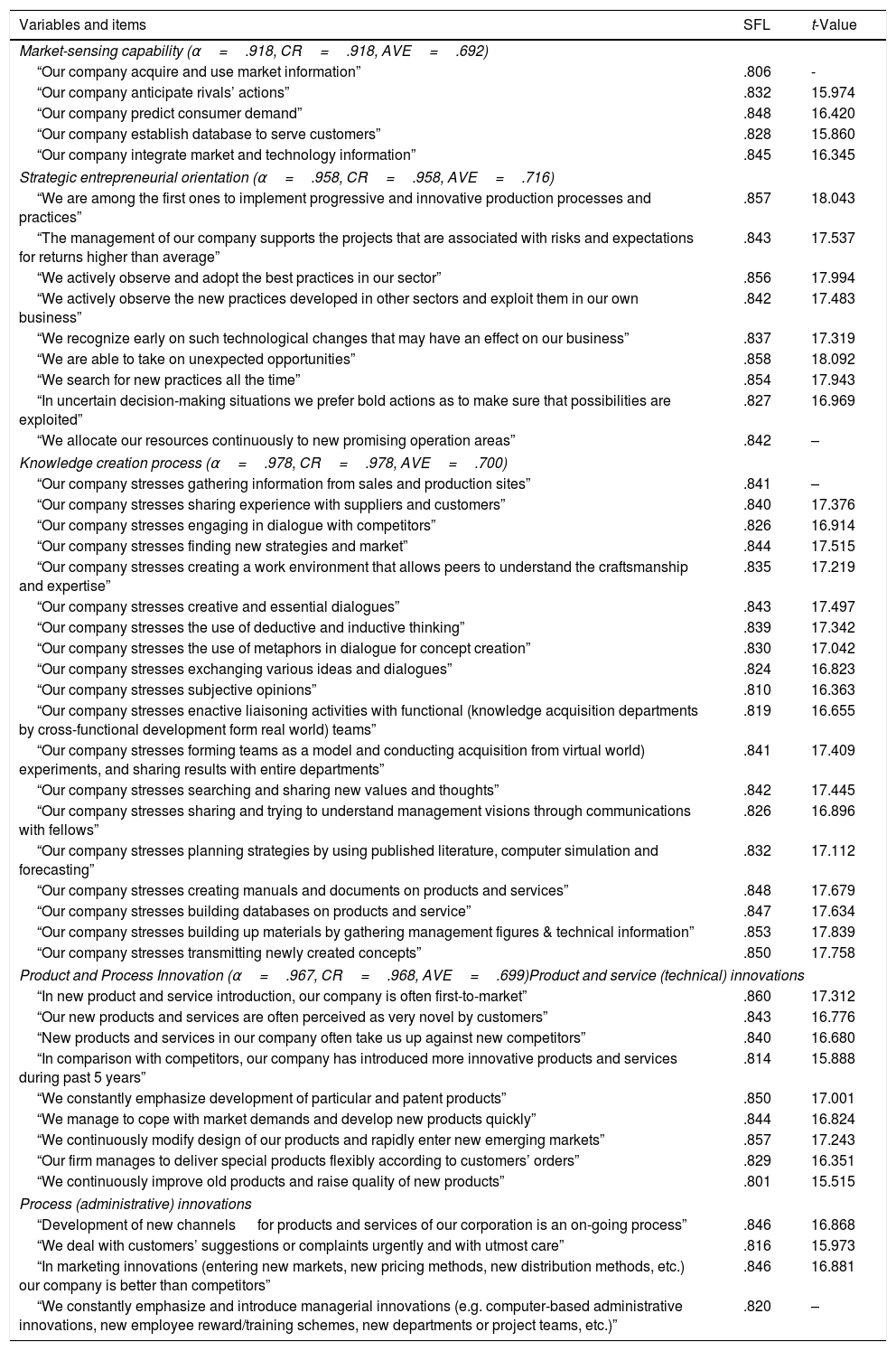

Table 3 presents the SFL values of the measurement model which were all above the threshold of .50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), SFL coefficients were between .801 and .860, and the t-statistics of the respective items were between 15.515 and 18.092. Table 3 also presents the CR values, all of which were also above the threshold of .70 (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010), similarly, the AVE coefficients explained by each construct were also above the threshold of .50 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Fornell & Larcker, 1981), and Cronbach alpha coefficients also exceeded the threshold of .70 (Cronbach, 1951). So far, the resultant values delineate that construct validity has been achieved, thus, we concluded that the constructs in the measurement model exhibit convergent and divergent properties.

Descriptive statistics of the survey items.

| Variables and items | SFL | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Market-sensing capability (α=.918, CR=.918, AVE=.692) | ||

| “Our company acquire and use market information” | .806 | - |

| “Our company anticipate rivals’ actions” | .832 | 15.974 |

| “Our company predict consumer demand” | .848 | 16.420 |

| “Our company establish database to serve customers” | .828 | 15.860 |

| “Our company integrate market and technology information” | .845 | 16.345 |

| Strategic entrepreneurial orientation (α=.958, CR=.958, AVE=.716) | ||

| “We are among the first ones to implement progressive and innovative production processes and practices” | .857 | 18.043 |

| “The management of our company supports the projects that are associated with risks and expectations for returns higher than average” | .843 | 17.537 |

| “We actively observe and adopt the best practices in our sector” | .856 | 17.994 |

| “We actively observe the new practices developed in other sectors and exploit them in our own business” | .842 | 17.483 |

| “We recognize early on such technological changes that may have an effect on our business” | .837 | 17.319 |

| “We are able to take on unexpected opportunities” | .858 | 18.092 |

| “We search for new practices all the time” | .854 | 17.943 |

| “In uncertain decision-making situations we prefer bold actions as to make sure that possibilities are exploited” | .827 | 16.969 |

| “We allocate our resources continuously to new promising operation areas” | .842 | – |

| Knowledge creation process (α=.978, CR=.978, AVE=.700) | ||

| “Our company stresses gathering information from sales and production sites” | .841 | – |

| “Our company stresses sharing experience with suppliers and customers” | .840 | 17.376 |

| “Our company stresses engaging in dialogue with competitors” | .826 | 16.914 |

| “Our company stresses finding new strategies and market” | .844 | 17.515 |

| “Our company stresses creating a work environment that allows peers to understand the craftsmanship and expertise” | .835 | 17.219 |

| “Our company stresses creative and essential dialogues” | .843 | 17.497 |

| “Our company stresses the use of deductive and inductive thinking” | .839 | 17.342 |

| “Our company stresses the use of metaphors in dialogue for concept creation” | .830 | 17.042 |

| “Our company stresses exchanging various ideas and dialogues” | .824 | 16.823 |

| “Our company stresses subjective opinions” | .810 | 16.363 |

| “Our company stresses enactive liaisoning activities with functional (knowledge acquisition departments by cross-functional development form real world) teams” | .819 | 16.655 |

| “Our company stresses forming teams as a model and conducting acquisition from virtual world) experiments, and sharing results with entire departments” | .841 | 17.409 |

| “Our company stresses searching and sharing new values and thoughts” | .842 | 17.445 |

| “Our company stresses sharing and trying to understand management visions through communications with fellows” | .826 | 16.896 |

| “Our company stresses planning strategies by using published literature, computer simulation and forecasting” | .832 | 17.112 |

| “Our company stresses creating manuals and documents on products and services” | .848 | 17.679 |

| “Our company stresses building databases on products and service” | .847 | 17.634 |

| “Our company stresses building up materials by gathering management figures & technical information” | .853 | 17.839 |

| “Our company stresses transmitting newly created concepts” | .850 | 17.758 |

| Product and Process Innovation (α=.967, CR=.968, AVE=.699)Product and service (technical) innovations | ||

| “In new product and service introduction, our company is often first-to-market” | .860 | 17.312 |

| “Our new products and services are often perceived as very novel by customers” | .843 | 16.776 |

| “New products and services in our company often take us up against new competitors” | .840 | 16.680 |

| “In comparison with competitors, our company has introduced more innovative products and services during past 5 years” | .814 | 15.888 |

| “We constantly emphasize development of particular and patent products” | .850 | 17.001 |

| “We manage to cope with market demands and develop new products quickly” | .844 | 16.824 |

| “We continuously modify design of our products and rapidly enter new emerging markets” | .857 | 17.243 |

| “Our firm manages to deliver special products flexibly according to customers’ orders” | .829 | 16.351 |

| “We continuously improve old products and raise quality of new products” | .801 | 15.515 |

| Process (administrative) innovations | ||

| “Development of new channels for products and services of our corporation is an on-going process” | .846 | 16.868 |

| “We deal with customers’ suggestions or complaints urgently and with utmost care” | .816 | 15.973 |

| “In marketing innovations (entering new markets, new pricing methods, new distribution methods, etc.) our company is better than competitors” | .846 | 16.881 |

| “We constantly emphasize and introduce managerial innovations (e.g. computer-based administrative innovations, new employee reward/training schemes, new departments or project teams, etc.)” | .820 | – |

Note: CR, construct reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; α, Cronbach's alpha; SFL, standardized factor loadings; –* discarded items during confirmatory factor analysis.

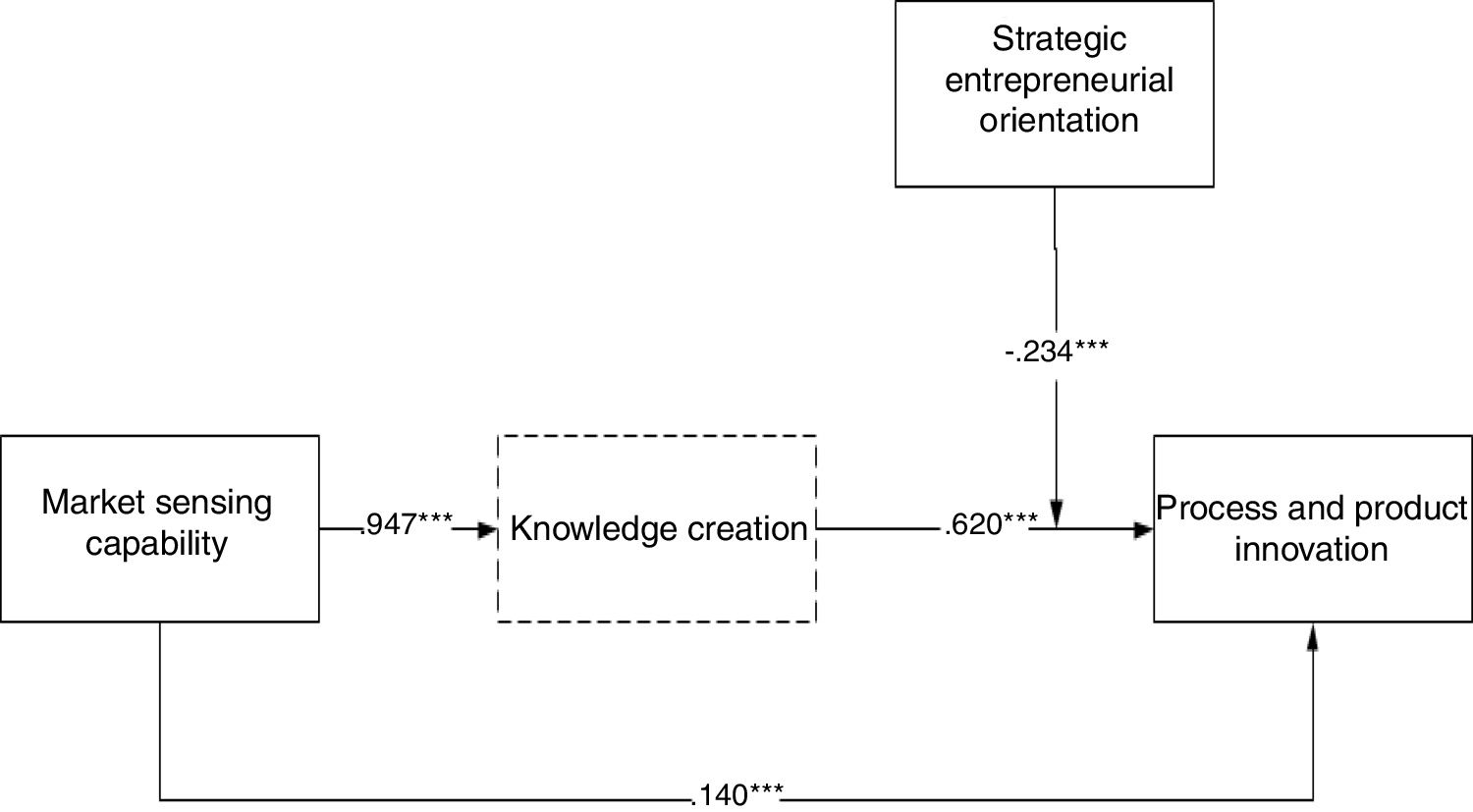

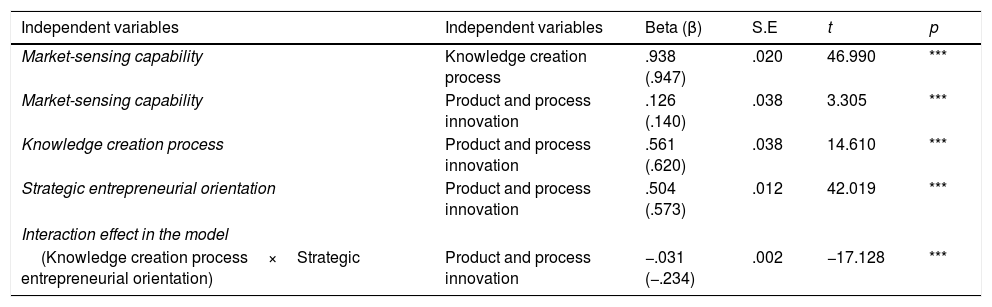

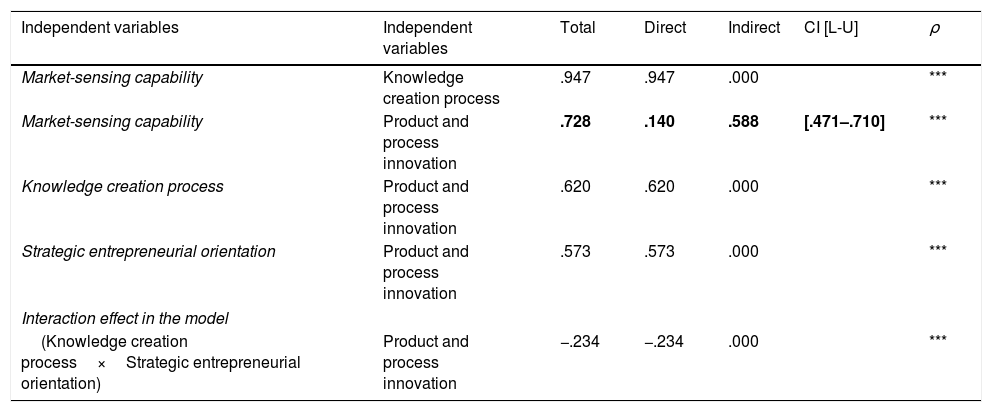

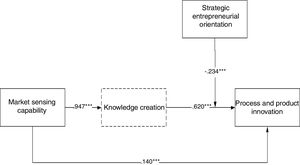

Results from SEM illustrates that the direct path between market-sensing capability and knowledge creation process (β=.947, p<.001) is positive and significant, in support of H1. Correspondingly, the direct path between market-sensing capability and product and process innovation (β=.140, p<.001) is positive and significant, in support of H2. In regard to the relationship between the knowledge creation process and product and process innovation, estimation results show that the relationship is positive and significant (β=.620, p<.001), in support of H3. Hypothesis 4, results show that market-sensing capability has a positive and significant indirect effect on product and process innovation through knowledge creation process (β=.588, p<.01).

Prominent scholars like Hayes (2013) and Hayes (2015) argued that “one of the beauties of bootstrapping is that the inference is based on an estimate of the indirect effect itself, but unlike the Sobel test, it makes no assumptions about the shape of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect, thereby getting around this problem that plagues the Sobel test”. Based on this claim, the current study employed bootstrapping analysis to test the mediation effect. The bias-corrected estimate (n=5000) suggested a partical mediation as follows (95% confidence interval: .471 and .710). Following (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) suggestions. This outcome lends support to H4. See Tables 4 and 5. Further, the researchers present the effect size of each link diagrammtically in Fig. 2.

Results from SEM.

| Independent variables | Independent variables | Beta (β) | S.E | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market-sensing capability | Knowledge creation process | .938 (.947) | .020 | 46.990 | *** |

| Market-sensing capability | Product and process innovation | .126 (.140) | .038 | 3.305 | *** |

| Knowledge creation process | Product and process innovation | .561 (.620) | .038 | 14.610 | *** |

| Strategic entrepreneurial orientation | Product and process innovation | .504 (.573) | .012 | 42.019 | *** |

| Interaction effect in the model | |||||

| (Knowledge creation process×Strategic entrepreneurial orientation) | Product and process innovation | −.031 (−.234) | .002 | −17.128 | *** |

Note: Beta, unstandardized estimates, β, standardized estimates; S.E, standard error; t, t-value; *Significance level p<0.05; ***significance level p<0.01.

Effects breakdown (standardized).

| Independent variables | Independent variables | Total | Direct | Indirect | CI [L-U] | ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market-sensing capability | Knowledge creation process | .947 | .947 | .000 | *** | |

| Market-sensing capability | Product and process innovation | .728 | .140 | .588 | [.471–.710] | *** |

| Knowledge creation process | Product and process innovation | .620 | .620 | .000 | *** | |

| Strategic entrepreneurial orientation | Product and process innovation | .573 | .573 | .000 | *** | |

| Interaction effect in the model | ||||||

| (Knowledge creation process×Strategic entrepreneurial orientation) | Product and process innovation | −.234 | −.234 | .000 | *** | |

Note: Total, Total effects, Direct, Direct effects, Indirect, Indirect effects, CI, Confidence Interval; L, lower bound; U, upper bound.

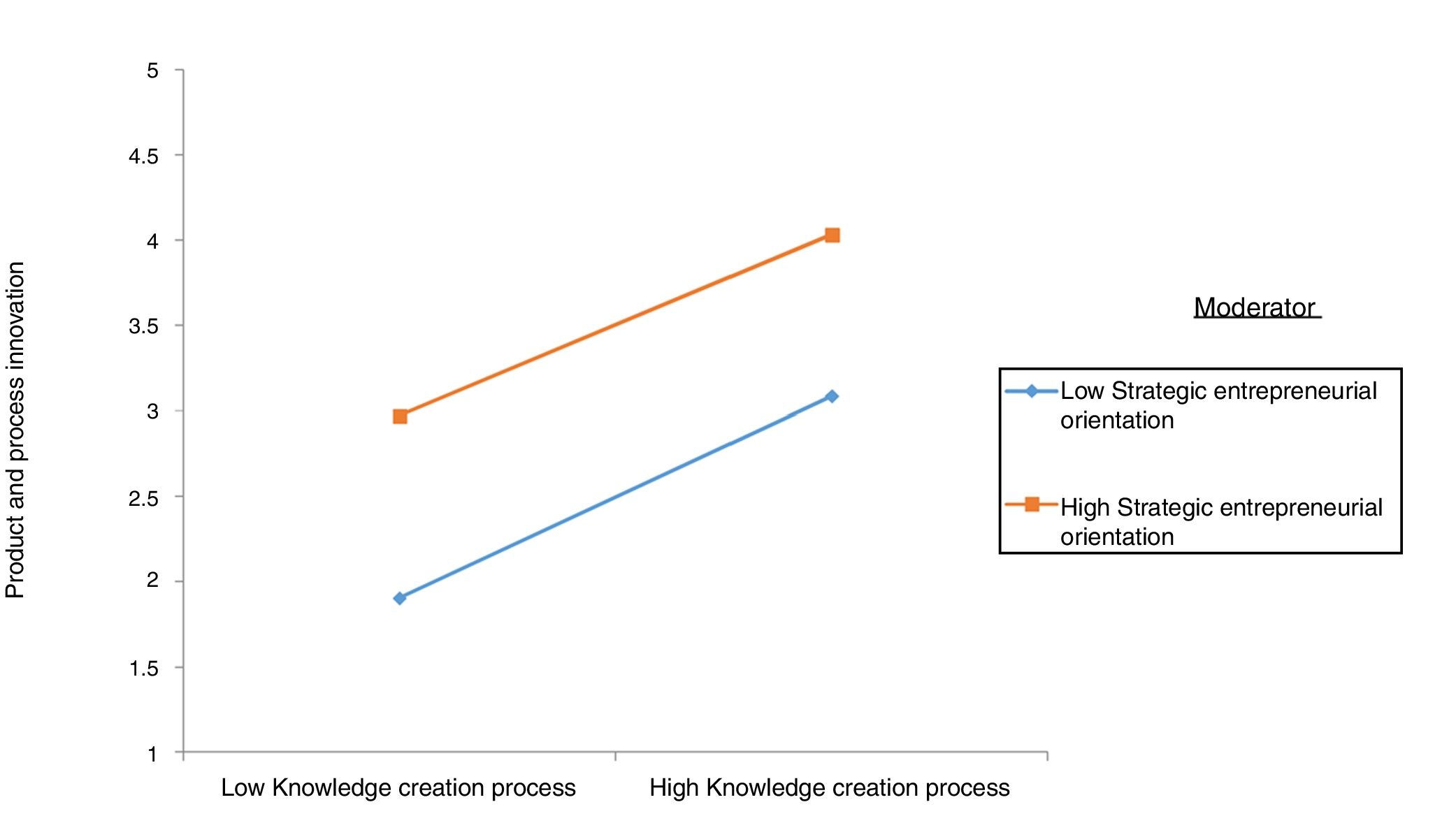

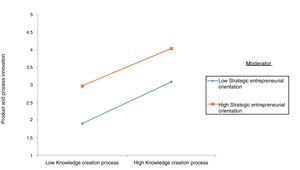

To test moderation effect, we followed (e.g., Aiken et al., 1991) suggestions. We found that strategic entrepreneurial orientation had a direct positive impact on product and process innovation (β=.573, p<.001). Conversely, knowledge creation process×strategic entrepreneurial orientation interaction suggests that strategic entrepreneurial orientation dampens the positive relationship between knowledge creation process and product and process innovation (β=−.234, p<.001). See Fig. 3, Tables 4 and 5. Thus, hypothesis 5 was rejected.

DiscussionMore numbers of business and management research are carried out on larger firms than on SMEs. Yet SMEs are a huge contributor to the economic and social development of most economies; developing and developed alike (Lin, 1998). Thus, empirically supporting theories, practices, and methodologies of SMEs are vital for practitioners as well as academicians. We found that SMEs that possesses good market-sensing capabilities would be able to create knowledge. This is in agreement with Ardyan (2016) suggestion that when SMEs senses the market, their primary goal is not enterprise profit or growth but to possess the knowledge of what their consumers need and then use the knowledge to offer appropriate product and services based on the customer's need.

Two, SMEs that possesses good market-sensing capabilities would be more innovative more than those that do not. This outcome is similar to those obtained by previous research (Keskin, 2006), where the results revealed that the higher the ability of an enterprise to sense the market the better and more effective it becomes at being innovative.

Three, knowledge creation process has a substantial positive association with product/process innovation. Previous studies (Binbin, Jiangstao, Mingxing, & Tongjian, 2012), have identified the role the knowledge creation process of a firm plays in its innovativeness. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) particularly highlighted knowledge creation process as the facilitator for innovativeness in a firm. The contribution that makes our finding distinct is the Arabian and SMEs context, as little has been done. Four, knowledge creation mediated the link between market-sensing capabilities and product/process innovation. Knowledge obtained from market sensing becomes the resource that SMEs can use to ensure continuous innovation. In Lindblom, Olkkonen, Kajalo, and Mitronen (2008) study of retail entrepreneurs, it was found that the capability to sense the market and business performance such as innovation has a rather weak relation. They explained that this could be so because other factors influencing the association between market-sensing and performance such as innovation was not considered in their model/analysis and one of such factor could be the process of knowledge creation.

Five, this study's results did not confirm that a connectedness exist among product/process innovation, strategic entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process. In particular, the results show that strategic entrepreneurial orientation does moderates the relationship between knowledge creation process and process/product innovation, but instead of amplifying the effect of knowledge creation on innovation. We found that it lowers the positive effect. Prior studies such as Weerawardena (2003) argued that firm's unique capabilities like the knowledge creation process, entrepreneurship orientation and innovation are strongly related. A firm's innovativeness is essentially the outcome of its knowledge creation process. Gleaning from the RBV (Barney, 1991), firms having superior strategic entrepreneurial orientation, profit more from their knowledge creation process because these enterprises can effectively exploit the knowledge stockpile and knowledge resources available from the knowledge creation process of the firm (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). On the other hand, firms with low strategic entrepreneurial orientation, although they may also benefit meagerly from the knowledge creation process of their organization, innovativeness and risk-taking behaviours are rare, thus, resulting to low innovation capabilities. Given the extant claim in the literature and the current finding, we opined that cultural and other environment forces might be the reason strategic entrepreneurial orientation lowers the impact of knowledge creation on innovation. More research is required to solve the present dilemma.

Implications for theorySmall and medium enterprises cover major employment, novelty, social and financial growth in the advanced and less advanced nation. Thus, enhancing entrepreneurial based investigation, procedure, an approach is essential for both researchers and specialists. Following the higher level of concern between researchers and specialists in an innovative firm, research exertions which incorporate the market recognition planned entrepreneurial orientation and invention will be enormously valued, since strategic marketing research has contributed a somewhat little portion to experimental study in line with planned entrepreneurial orientation.

Knowledge formation phenomenal is reproductive, in the sense that the model and projected interactions can be applied in total or in parts to produce various development in managing and firm's theory. The idea of knowledge as a means in a firm is a significant matter that deserves many concepts in constructing and research. The further experimental expansion is instantly desired on the interrelationship among “knowledge model”: as the ability and as a resource in knowledge formation concept among small medium enterprises.

Capturing insights from studies and hypotheses testing, our experiment produces the first analysis of certain hypothetical link those independent variables of the study. Whereas, marketing literature proposed the significance of market-centred informational knowledge that supports knowledge formation theory, through spreading and relating the theory to market sensing competence factors, product and method innovative variable together with deliberate entrepreneurial positioning. The findings produce practical backing for knowledge formation concept, the tendency to reconcile the association amongst market sensing abilities and novelty; it also exerts a straight influence on a firm's innovation.

Implications for practiceDrawing insight from the hypotheses, it has been recognized that information is key for every organization, also for SME's operation. Experimental results revealed that market sensing abilities of an enterprise are important for SME's improvement. However, market sensing is required for active learning-positioning in SMEs. Furthermore, market sensing is adopted with learning-positioning for firm effectiveness. Information Financiers obtain from, consumers, rivals, and majorly from the market, affects how they explore, how they attend to, and how they relate the result for the innovative and overall function of knowledge.

SME performance hypothesized as product and process innovation which emanate from the relationship between market sensing, information and strategic entrepreneurial positioning. However, shows that both direct and indirect impacts are essential for SMEs operation. It is suggested that SMEs managers need to harmonize their procedure concerning market sensing, learning and entrepreneurial orientation. The existence of an exigency fit well with these research paradigms that make firm function perfectly.

Therefore, it looks realistic to note that market sensing actions and openness are motivated by and found on the entrepreneurial orientation that promotes reactiveness, innovation, and risk-taking which prioritize every aspect in good times. Thus, SME managers are directed to be both entrepreneurial and possess market intelligence. It is worthy of note that entrepreneurial positioning only is inadequate; the inability to identify market needs via sensing actions and equate them with proper know-how could stunt SMEs growth rate.

The focus point of market information handling embedded in organizational learning has incredible ability to make SMEs financiers and managers set to utilize opportunities whenever it surfaces, also to pursue innovative thoughts that meet market needs. Market sensing ability acquired through instability and ambiguity is principal for firm's operation, irrespective of how performance is operationalized. A financier or an organization that tends to avoid such action on a constant basis is courting for a detrimental end, depending on the complexity of the business environs.

Research explicitly posited that knowledge transmission is an additional essential phase of knowledge formation model in the organization. Marketing consultants and entrepreneurs are pacified to share market knowledge acquired from sensing action with other organizations. This confirms that their knowledge source is handy with treasured information and that each personnel are endowed to perform. Business owners and managers can strongly increase their capability to actively employ fundamental innovation of their service and products improvement, to foster competitive advantage. The main findings had been of concern since they infer method of improving firm's level of performance. SMEs management should strive to expand the total level of market knowledge, although residual ability able to reserve a knowledge and business orientation as market circumstances ensue.

Limitations and future research directionsApplicable to most empirical studies, the present study inherits several limitations. One, the sample is limited to Jordan a small Arab nation with limited resources. Although, procedural and statistical approaches were deployed to gauge for potential threats of CMB. The data used in this study is self-reported in nature, and the design is cross-sectional; these limits and/or interfere with causality among the variables under investigation. The author(s) suggest that future research can employ longitudinal design and multi-source data to validate the present findings and abate CMB. Further insights can be acquired by exploring in depth the impact of environmental factors surrounding strategic entrepreneurial orientation. Big Data analytics has emerged as powerful tool for market intelligence, it will be imperative to diagnose how Big Data analytics can boost market-sensing capability and how these could be translated into knowledge pool for the purpose of innovation. The author(s) believe that such research endeavours would contribute to the existing literature.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest, and this research did not receive any grants.