This study investigates the effect of intangible resources and entrepreneurial orientation in export performance, by examining the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities. A framework of export antecedents is developed and empirically tested. A survey of 265 Portuguese exporting companies shows that dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation directly impact export performance while financial, informational and relational resources have an indirect impact in export performance through dynamic capabilities. These results point to the important role of dynamic capabilities, sheding light on how intangible resources can be used by companies to enhance export performance, highlighting also the role of entrepreneurial orientation to leverage business’ export performance.

Our findings have relevant theoretical implications. For the Dynamic Capabilities View (DCV) literature, given the support for the impact of dynamic capabilities in performance by leveraging the impact of resources, and for the entrepreneurship literature, given the finding that entrepreneurial orientation potentiates export performance. More importantly, our study provides support for these relationships in the context of international markets. Practical implications for export supporting policies are also noted.

The competition in international markets is particularly intense and companies need to compete to the best of their ability in this volatile environment (Morgan, Vorhies, & Schlegelmilch, 2006). As a consequence of ever-increasing globalisation, companies are faced with international competitors in their internal markets and must explore and develop commercial opportunities abroad (Etemad, 2005), highlighting the importance of defining adequate strategies for export markets (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994). Organizations which are ready for the new and constant challenges of the market will be more prepared and can thus resist in a more sustainable way to global competitiveness (Jaén & Liñan, 2013; Rojas, Morales, & Ramos, 2013).

The resource-based view (RBV) emphasises that the ownership of strategic resources enables companies to gain competitive advantage. Recent studies have changed the focus from tangible resources to intangible resources, which are deemed more important from a strategic viewpoint and more relevant for business performance and success (Bakar & Ahmad, 2010; Khan, Xuele, Atlas, & Khan, 2019; Monteiro, Soares, & Rua, 2017a, 2017b; Morgan et al., 2006; Rua, 2018; Rua & França, 2016; Rua, França, & Fernández, 2018). However, understanding how resources provide this competitive advantage remains unclear and this has been labeled as a “missing link” in the strategic management literature (Chatzoglou, Chatzoudes, Sarigiannidis, & Theriou, 2018).

Consequently, research has focused on the processes through which resources can be used by companies to outperform competitors. These processes include companies’ capabilities and competences (Chatzoglou et al., 2018; López, 2005; Teece, 2007; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Wu, 2010).

Hence, the Dynamic Capabilities View (DCV) has emerged in the field of strategic management, mainly in order understand the need for adjustment of companies to environmental change (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993; Teece et al., 1997) and due to the fact that companies’ success depends not only on their resources, but also on the ability to adapt themselves to the industry contingencies and the markets in which they operate. Bowman and Ambrosini (2003) state that firms may possess resources but they must also display dynamic capabilities, otherwise shareholder value will be destroyed. The DCV is not divergent but rather an important stream of the RBV to capture how companies can gain competitive advantage in increasingly demanding environments (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Barreto, 2010; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Lin & Wu, 2014; Wang & Ahmed, 2007).

With the steady increase of business and international competition, understanding the determinants of international performance, mainly in exports, has become particularly important, contributing to the development of several studies in this area (Sousa, Martínez-López, & Coelho, 2008).

However, despite much research on export performance, this topic remains one of the least understood and most contentious areas of international marketing. According to Katsikeas, Leonidou, and Morgan (2000), the relevance of this subject is mainly due to the need for companies to understand the process leading to better results in export markets. However, the lack of an integrative theoretical framework explaining export performance makes it difficult to integrate the results of different studies in a coherent body of knowledge (see Morgan, Kaleka, & Katsikeas, 2004; Sousa et al., 2008). Moreover, Sousa et al. (2008) suggest that future studies should focus on mediating variables in order to produce relevant insights for the analysis of the direct, indirect and total effects concerning export performance.

In fact, although the effect of resources on export performance has been studied, there is a need for further studies about the complex interconnection of intangible resources and capabilities and export performance. In fact, despite many studies about this topic “the contribution of dynamic capabilities to competitive advantage and firm performance remains unclear” (Pezeshkan, Fainshmidt, Nair, Lance Frazier, & Markowski, 2016, p. 2950).

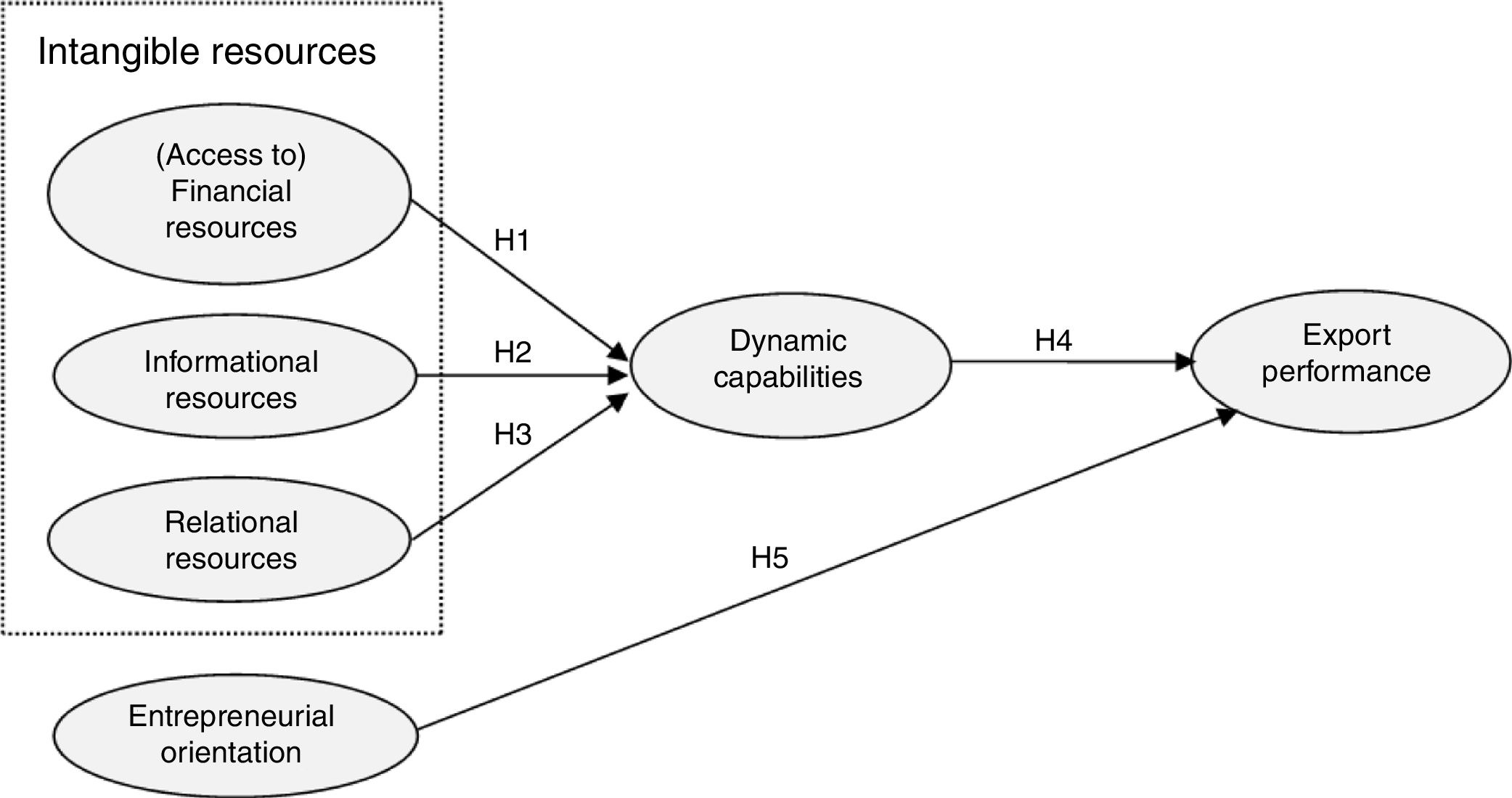

Our study provides insights into what has, in fact, been termed a “black box”: the processes through which resource value and rareness contribute to firm performance (Chatzoglou et al., 2018). In addressing this limitation of previous research, our study aims to advance the literature by examining the role of dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation in those processes in the context of exporting. So, the purpose of this paper is to broaden the boundaries of the strategic management and entrepreneurship literature by addressing the following research questions: Do dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between intangible resources and export performance? Additionally, does entrepreneurial orientation have a positive effect on export performance? A research model inspired on the studies conducted by Madsen, Alsos, Borch, Ljunggren, and Brastad (2007) in the context of small and medium (SMEs) Norwegian companies engaged in R&D activities, for one side, and Ferreira and Fernandes (2017) and França and Rua (2018) conducted with Portuguese footwear SMEs, for the other is developed and tested. These authors have called for validation studies in other industries and country settings. Therefore, our study is a step further to understand how entrepreneurial orientation and dynamic capabilities contribute for a better use of intangible resources, thus achieving higher performance in export markets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In the next section, we present the conceptual background of the study leading to the proposed model and hypotheses. Thereafter, the methodology and empirical study are presented. The final section is the discussion and conclusions, main findings and implications, limitations and directions for future research are also addressed.

Theoretical frameworkExport performanceExports remain one of the most important entry modes in international markets. Dhanaraj and Beamish (2003) and Fuchs and Köstner (2016) sustain that exports are a more attractive way to enter international markets in comparison with other alternatives, such as joint ventures or acquisitions, which involve spending a large number of resources. Lu and Beamish (2002) refer that exporting does not involve high risk and commitment and allows for greater flexibility in adjusting the volume of goods to different export markets. Lin and Ho (2019) emphazise that some firms can only internationalize through exports.

Market performance, in general is a “key expeted outcome of superior firm capabilities from the RBV standpoint” (Ricciardi, Zardini, & Rossignoli, 2018, p. 95). Export performance refers to the extent to which a company achieves its goals concerning exporting (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994). As such, this constitutes a very broad concept, referring to the firm's appraisal and evaluation of its export activity, depending on a wide range of strategic and marketing objectives. Consequently, how export performance has been conceptualized and measured varies greatly in the literature (Okpara, 2009; Sousa et al., 2008). Approaches to operationalizing export performance include objective measures such as sales volumes or market share and subjective indicators such as perceived export success or perceived satisfaction with sales in export markets. In general, export performance studies use multidimensional measures. Sousa et al.’s (2008) review concluded that although there is a large number of measures (about 50), export intensity (share of exports in total sales), growth of export sales, export profits, export market share, satisfaction with export performance in general and perceived export success are the most frequently used (Sousa et al., 2008).

Understanding the determinants of export performance and how companies can leverage their capabilities in order to be more effective than competitors in meeting their consumers’ needs and enhance their international competitiveness (Tan & Sousa, 2015) has been an important research direction. There are a number of export determinants which have been identified by research in international business studies. However, despite considerable attention, the literature on export performance has a number of limitations and inconsistencies (Sousa et al., 2008).

Dhanaraj and Beamish (2003) concluded that resources are good predictors of export strategy (operationalized in terms of degree of involvement in foreign markets). Similarly, Morgan et al. (2004) confirm that export performance is strongly correlated with the positional advantage of the firm in the international market and that this is directly related to the availability of resources and capabilities for external markets.

Resources and capabilitiesThe hallmark of the RBV is the premise that competitive advantage depends on strategic resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). Resources include tangible or intangible assets firms own, control or have access to in a semi-permanent basis (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003) and can include technological, financial, human, physical and organizational resources (Bakar & Ahmad, 2010; Loane & Bell, 2006). When a company is established, it either explicitly or implicitly employs a particular business model that describes the design or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and capture mechanisms (Teece, 2010). Resources should have some ability to generate profits or avoid losses (Miller & Shamsie, 1996). In this sense, the resources not only refer to the companies’ assets but also to their capabilities (Henderson & Cockburn, 1994).

The theoretical framework based on resources and strategic management has been refreshed by the Dynamic Capabilities View, which has emerged as promising area of research in strategic management (Fernandes et al., 2017; López, 2005; Teece, 2007; Teece et al., 1997; Wu, 2010). Capabilities refer to the firm's ability to perform a coordinated set of tasks, using organizational resources, in order to achieve a specific result (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003). Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) further argue that product development, strategic decision making, and alliancing have contributed to the dynamic capabilities as a set of specific and identifiable processes. Thus, this concept focuses on the firm's capacity to mobilize resources, generally in combination, using organizational processes, to a desired end effect attaining best competitive results (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993; Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017). According to Khan et al. (2019, p. 2), “dynamic capabilities involve adaptation and change, because these capabilities can be regarded as a transformer for converting resources into improved performance while creating competitive advantage”. As such, possessing resources is not enough for superior performance, companies need a set of dynamic capabilities to combine, develop and exploit those resources (Ferreira & Fernandes, 2017).

Dhanaraj and Beamish (2003) have studied three sets of resources and capabilities which influence and/or reinforce corporate strategy in external markets, specifically entrepreneurial orientation, organizational resources and technological intensity, and verified their positive impact in exporting and performance.

Our study focus specifically on financial, informational and reputational resources and on dynamic capabilities.

Financial resources are a resource type universally deployable through which other resources (e.g. know-how) can be acquired (Frank, Kessler, & Fink, 2010). Despite the financial constraints faced by many small and medium enterprises, some are able to make savings gradually, allowing them to invest in export operations (Leonidou, Katsikeas, Palihawadana, & Spyropoulou, 2007), while others face problems of access to credit in the financial market. According to Leonidou et al. (2007), the financial advantage can also be obtained by building strong relations with national financial institutions, which may later help companies in their exporting efforts by granting various credit facilities. In fact, for Morgan et al. (2006), the most important characteristics of the financial resources of an exporting company consist in the level of funding that can be accessed and the time limit within which this can happen. Financial resources contribute to achieve competitive advantage, as companies with more financial resources are in a better position to invest some of those resources to develop distinctive capabilities, contributing to their differentiation relative to their competitors (Cater & Cater, 2009) and for superior export performance (Morgan et al., 2006). Hence, the following is proposed:H1

Access to financial resources has a positive effect on dynamic capabilities.

Knowledge refers to any information, belief or ability that firms can incorporate into their activities (Anand, Glick, & Manz, 2002). Grant (1996) refers that knowledge is the most important firm asset. It has been emphasized that the lack of knowledge is the main barrier to the internationalization of small businesses (Loane & Bell, 2006). Internationalization is an information-intensive process and requires relevant, accurate and timely information about customers, competitors, distribution channels and export markets (Katsikeas & Morgan, 1994). This type of knowledge results from tacit knowledge (acquired from experience) and can lead to the identification of opportunities, market knowledge, and networking, encouraging internationalization (Mcdougall, Oviatt, & Shrader, 2003). Nielsen (2006, p. 68) indicates that “the different dynamic capabilities create flows to and from the firms stock of knowledge”. For Chien and Tsai (2012), the greater the informational resources a firm has accumulated, the better it can develop its dynamic capabilities. Indeed, several studies found that knowlwdge/information is significantly related with the dynamic capability (Chien & Tsai, 2012; Monteiro et al., 2017a; Tsend & Lee, 2014). Hence:H2

Informational resources have a positive effect on dynamic capabilities.

Relational resources consist of the networks between the company and external entities such as customers, suppliers, competitors and government institutions (Davis & Mentzer, 2008). For Dina (2013, p. 76), relational resources “could be cultivated in the relationship between an organization and its internal and external stakeholders as well as in their interactions”. These resources are based on relationships, understood as promising sustainable competitive advantage, in that resources are distributed asymmetrically between firms, imperfectly mobile, difficult to imitate and have no substitutes available (Barney, 1991). Currently, the struggle for competitive advantage in a globalized economy increasingly revolves around the value of firms’ networks (Davis & Mentzer, 2008). According to Otola, Ostraszewska, and Tylec (2013), relational resources are seen as valuable and precious resources that ensure the firm's success in the market. However, a firm must establish relations not only in terms of expected performance, but also for the improvement of capabilities that allow for the development of other resources (Arndt, 1979). In the literature, the relational resources have recently been reflected from the dynamic capability (Eloranta and Turunen, 2015). In addition, Monteiro et al. (2017a) found that relational resources have a positive and significant impact on the development of dynamic capabilities. Hence:H3

Relational resources have a positive effect on dynamic capabilities.

Several authors consider that the theory of resources and capabilities does not adequately explain how companies achieve competitive advantage in fast moving business environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997). In these business landscapes, technological change is fast, the nature of the markets and competition is difficult to determine and time-to-market is critical (Teece et al., 1997). In versatile markets, capabilities must be dynamic, namely the firm must have the capability to renew competencies to continually ensure the consistency between the business environment and strategy.

Recent research has been focusing on dynamic capabilities as a source of sustainable competitive advantage (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Fernandes et al., 2017; Lin & Wu, 2014; Teece, 2007; Teece et al., 1997). For Teece et al. (1997, p. 515), the term dynamic refers to the “capacity to renew competences so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment”. These authors define dynamic capabilities as the firm's ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to quickly respond to changes in the current business environment. Dynamic capabilities allow to convert resources into competitiveness (Lin & Wu, 2014). According to Khan et al. (2019), dynamic capabilities positively influence firm performance. Hence, the following is proposed:H4

Dynamic capabilities have a positive impact on export performance.

Entrepreneurial orientationEntrepreneurial orientation has become an hot topic in business research due to its key role as “a driving force behind the organizational pursuit of entrepreneurial activities” (Covin & Wales, 2012, p. 677). The literature has emphasize the multifaceted outcomes of entrepreneurial orientation and how it leads to superior performance (Kollmann & Stöckmann, 2014). Miller (1983) states that an organization with entrepreneurial orientation bets on the innovation of poducts and/or markets with some risk and acts proactively before its competition. For Lumpkin and Dess (1996, p. 136), entrepreneurial orientation “refers to the processes, practices, and decision-making activities that lead to new entry”.

Previous research has suggested that entrepreneurial orientation is a multidimentional construct. According to Miller (1983), entrepreneurial orientation includes three main dimensions: innovation, risk taking and proactiveness. Two more dimensions, competitive aggressiveness and autonomy, were proposed by Lumpkin and Dess (1996). Thus, according to these authors, the main dimensions that characterize an entrepreneurial orientation include a tendency to act autonomously; a willingness to innovate and take risks and a tendency to be aggressive toward competitors and proactive in terms of market opportunities. This is corroborated by Pearce, Fritz, and Davis (2010) who refer that entrepreneurial orientation is regarded as a set of distinct behaviors such as innovation capability, proactivity, competitive aggressiveness, risk assumption, and autonomy. However, the dimensions most commonly used in research are: innovativeness, proactiveness and risk taking (Kropp, Lindsay, & Shoham, 2008). According to Miller (1983), only companies that have a high level in all three dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation would be considered potentially entrepreneurial. The relation between entrepreneurial orientation and export performance has also been studied. Previous research suggests that resources and capabilities are related (Dhanaraj & Beamish, 2003; Morgan et al., 2004) and sustains that entrepreneurs have a unique cognitive ability of to recognize venture opportunities and organize resources (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001). Nevertheless, further research on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance in the context of changing markets is needed to enhance theory development in the field (Jantunen, Puumalainen, Saarenketo, & Kyläheiko, 2005). Thus, we intend to test the following hypothesis:H5

Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive effect on export performance.

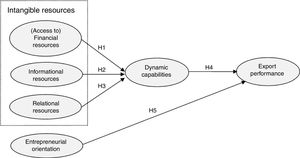

Fig. 1 presents the proposed research model and hypotheses.

MethodologyThis study follows a quantitative methodological approach to test the proposed model by using a questionnaire to collect data, which is consistent with the majority of studies in the literature on export performance (Sousa et al., 2008).

After collecting data, we proceed to statistical analysis using structural equation modeling (SEM), which is a statistical technique which specifies that latent variables present a direct or indirect impact in the values of other latent variables included in the model (Byrne, 1998). This analysis involved three phases: (1) preliminary analysis of the data, (2) evaluation of the measurement model, and (3) evaluation of the structural model. In the first phase, we prepared the data for analysis, which consists of the treatment of the missing-values, an analysis of the outliers, central tendency and normality, sample dimension, and, also an analysis of the non-response bias. Subsequently, we proceeded to the characterization of the sample. In the second phase, the measurement model was evaluated in terms of the unidimensionality, reliability and validity of the constructs (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998; Rubio, Berg-Weger, & Tebb, 2001; Ketchen, Hult, & Kacmar, 2004). Finally, the structural model was assessed to test the hypothesis. The statistical analysis was carried out using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and LISREL.

Setting and data collectionA survey was carried out with Portuguese exporting companies in Northern Portugal from November 2011 to February/2012. The choice of a single country is consistent with the literature (Sousa et al., 2008). Additionally, the option for Portuguese firms is relevant given the country's economic situation and its strong dependence on exports (Sousa & Bradley, 2006). The Portuguese official statistics body directory of exporting companies was used. This list includes micro-, small-, medium- and large-sized companies according to the European Union definition. Given the high number of exporting companies listed (17,330 firms listed in National Institute of Statistics), we focused on exporting firms in the northern region (6,653 records). This is also consistent with the literature in that several studies restrict the analysis to certain regions of one country (Sousa et al., 2008). A total of 1,510 exporters that provided e-mail addresses were retrieved from the database.

Based on extant research on this area, we focused on the “export venture”, which refers to combination of a single product or product line exported to the main market (Lages & Montgomery, 2004; Sousa et al., 2008). Focus on “export venture” allows a more accurate assessment of the factors associated with superior performance in terms of exports (Piercy, Kaleka, & Katsikeas, 1998).

The questionnaire was pre-tested with academics and exporting firms to identify potential difficulties with the instrument and provide suggestions for improvement. The final questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part included information about the firm and its export activity. The second part consisted of questions related to intangible resources (access to financial resources, informational and relational resources), entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities, and export performance.

A link to the online questionnaire was sent by e-mail to top managers and/or export managers. Subsequently, two e-mail reminders and follow-up telephone calls were used to increase the response rate. A total of 293 questionnaires were received, 265 of which were usable, representing a response rate of 19.4% and 18% respectively, which is quite satisfactory since the average response rate of top management is between 15% and 20% (Menon, Bharadwaj, Adidam, & Edison, 1999). SPSS statistical software (version 19) and LISREL (version 8.8) were used for data analysis.

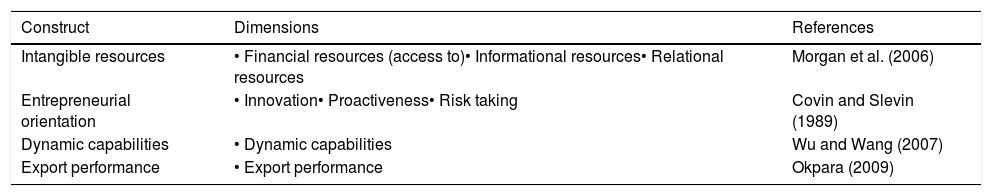

MeasuresThis study uses previously validated scales from the literature to operationalize the key constructs which were adapted to the particular context of our empirical setting.

Independent variables – Intangible resources include three dimensions – financial resources, informational resources and relational resources. We measured financial, informational and relational resources using Morgan et al.’s (2006) measurement scale. A seven-point scale ranging from much worse to much better was used. This scale is deemed to adequately capture the resources needed for export markets (Morgan et al., 2006), and has been widely used in previous studies, confirming its validity (Aaby & Slater, 1989; Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Rua & França, 2016; Venkatraman, 1986). In relation to entrepreneurial orientation, we used Covin and Slevin's (1989) measurement scale, including three dimensions: innovation, proactiveness and risk taking. A seven-point semantic differential scale was used to measure these items. According to Kropp et al. (2008), this is the most used scale in the operationalization of entrepreneurial orientation.

Mediator variable – We used Wu and Wang's (2007) measurement scale for capturing dynamic capabilities. A seven-point scale ranging from much worse to much better was used. This scale has earned an increasing attention from scholars to assess dynamic capabilities (Rua & França, 2016; Tuan & Takahashi, 2009).

Dependent variable – Export performance was measured by adopting Okpara's (2009) scale, which has often been used by several scholars (Abiodun & Rosli, 2014; França & Rua, 2016). All items were measured using a seven-point Likert scale.

Table 1 displays the referred measurement scales.

Measurement scales used in the questionnaire.

| Construct | Dimensions | References |

|---|---|---|

| Intangible resources | • Financial resources (access to)• Informational resources• Relational resources | Morgan et al. (2006) |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | • Innovation• Proactiveness• Risk taking | Covin and Slevin (1989) |

| Dynamic capabilities | • Dynamic capabilities | Wu and Wang (2007) |

| Export performance | • Export performance | Okpara (2009) |

In this study the majority of responses were collected after follow-up. To assess differences between groups, we compared the means for the respondents in the first group (first quartile) and second group (fourth quartile) for all variables included in the conceptual framework using Mann–Whitney U test. Results show that although most of the late responses averages are higher than those of the initial responses, the differences are not statistically significant (p>0.05) and consequently non-response bias is not a significant problem in this study.

ResultsThe results are based on the responses provided by a majority of small and medium companies (78.1%), large companies are 8.7% and micro companies are 13.2% of the sample. Regarding export activity, 49.1% have been exporting for more than 15 years, 33% for 6–15 years, 13.2% for 3–5 years and 4.5% for less than 3 years. Additionally, 52.8% of the firms export more than 40% of the total sales and 44.2% export to 6–15 countries.

To test the proposed framework, we used structural equation modeling as the theoretical model includes complex relationships among latent variables, and measures of different items that are presented simultaneously as independent and dependent variables (Bentler, Bagozzi Cudeck, & Iacobucci, 2001; Hair et al., 1998). We started by assessing the model fit, then, the structural model of path analysis was examined.

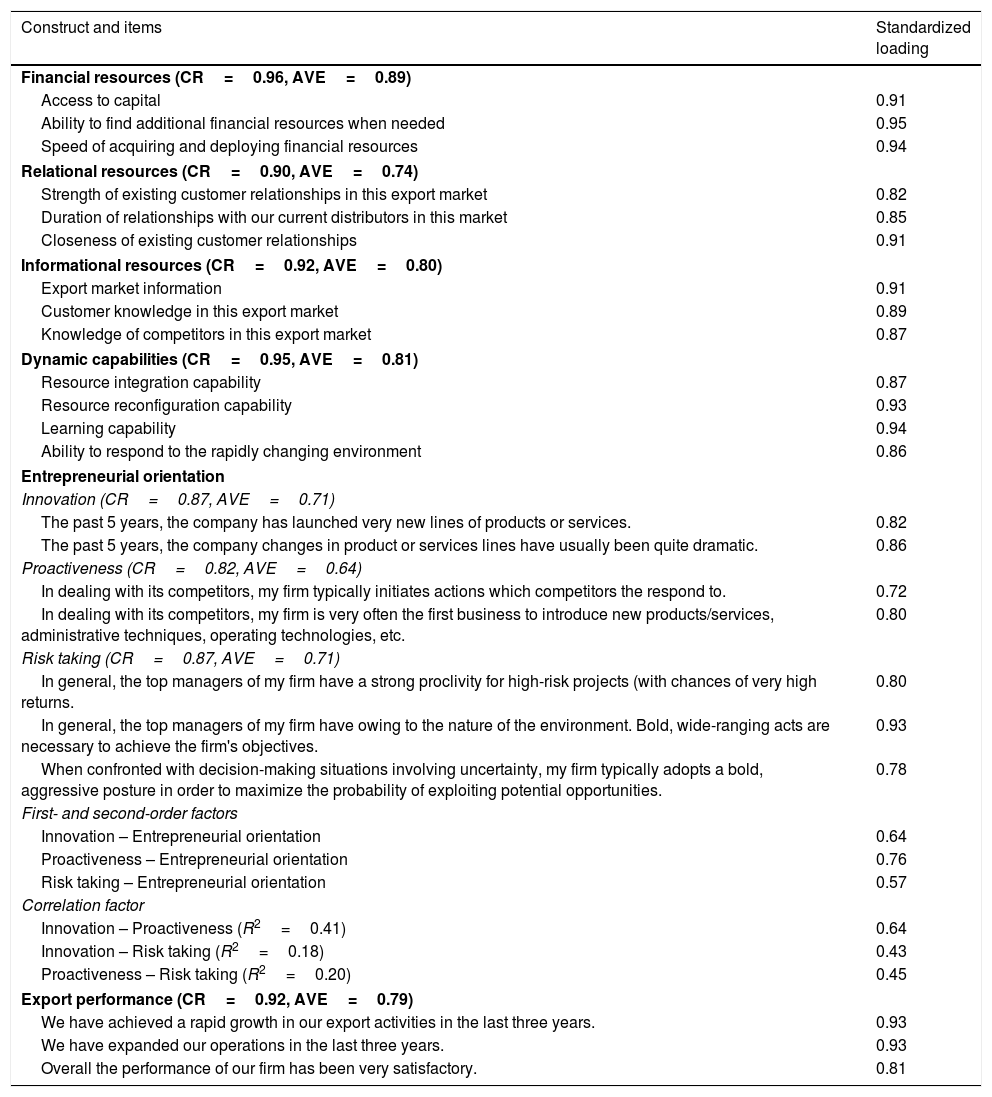

The analysis of the measurement model was evaluated in terms of constructs unidimensionality, reliability and validity (convergent and discriminant) and the results are shown in Table 2. In the first-order models, all items relate significantly to factor in terms of loadings and statistically, thus demonstrating the unidimensionality of the single factor and all loadings of the observed variables have values greater than 0.70, demonstrating the existence of convergent validity of the constructs (Garver & Mentzer, 1999). All latent variables have a good level of composite reliability (CR), with values greater than 0.60, which proves the reliability of the scales (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). The average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.50, providing evidence for discriminating validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In the second-order models, the statistical significance of associations between factors of first and second order is confirmed, the coefficients exceed the minimum threshold of 0.40, confirming the convergent validity of the construct (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) and the square of the correlation is less than the average variance extracted for each factor evidencing discriminant validity of the construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Measurement model results.

| Construct and items | Standardized loading |

|---|---|

| Financial resources (CR=0.96, AVE=0.89) | |

| Access to capital | 0.91 |

| Ability to find additional financial resources when needed | 0.95 |

| Speed of acquiring and deploying financial resources | 0.94 |

| Relational resources (CR=0.90, AVE=0.74) | |

| Strength of existing customer relationships in this export market | 0.82 |

| Duration of relationships with our current distributors in this market | 0.85 |

| Closeness of existing customer relationships | 0.91 |

| Informational resources (CR=0.92, AVE=0.80) | |

| Export market information | 0.91 |

| Customer knowledge in this export market | 0.89 |

| Knowledge of competitors in this export market | 0.87 |

| Dynamic capabilities (CR=0.95, AVE=0.81) | |

| Resource integration capability | 0.87 |

| Resource reconfiguration capability | 0.93 |

| Learning capability | 0.94 |

| Ability to respond to the rapidly changing environment | 0.86 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | |

| Innovation (CR=0.87, AVE=0.71) | |

| The past 5 years, the company has launched very new lines of products or services. | 0.82 |

| The past 5 years, the company changes in product or services lines have usually been quite dramatic. | 0.86 |

| Proactiveness (CR=0.82, AVE=0.64) | |

| In dealing with its competitors, my firm typically initiates actions which competitors the respond to. | 0.72 |

| In dealing with its competitors, my firm is very often the first business to introduce new products/services, administrative techniques, operating technologies, etc. | 0.80 |

| Risk taking (CR=0.87, AVE=0.71) | |

| In general, the top managers of my firm have a strong proclivity for high-risk projects (with chances of very high returns. | 0.80 |

| In general, the top managers of my firm have owing to the nature of the environment. Bold, wide-ranging acts are necessary to achieve the firm's objectives. | 0.93 |

| When confronted with decision-making situations involving uncertainty, my firm typically adopts a bold, aggressive posture in order to maximize the probability of exploiting potential opportunities. | 0.78 |

| First- and second-order factors | |

| Innovation – Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.64 |

| Proactiveness – Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.76 |

| Risk taking – Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.57 |

| Correlation factor | |

| Innovation – Proactiveness (R2=0.41) | 0.64 |

| Innovation – Risk taking (R2=0.18) | 0.43 |

| Proactiveness – Risk taking (R2=0.20) | 0.45 |

| Export performance (CR=0.92, AVE=0.79) | |

| We have achieved a rapid growth in our export activities in the last three years. | 0.93 |

| We have expanded our operations in the last three years. | 0.93 |

| Overall the performance of our firm has been very satisfactory. | 0.81 |

Notes: CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted. All loadings are statistically significant at p<0.001.

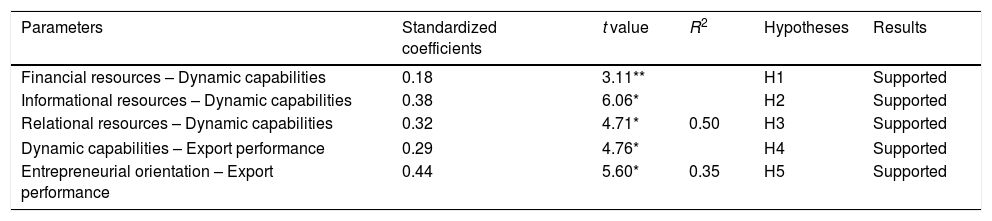

In order to test the proposed hypotheses the structural model was estimated.

The evaluation of the structural model was done under a partial aggregation perspective (average of the values corresponding to the items that measure each factor), since the analysis under the total disaggregation forecast becomes, according to Bagozzi and Heatherton (1994) impracticable when the sample is large and when the construct has more than four indicators. According to Baumgartner and Homburg (1996), the creation of composites (the items of each latent variable are organized in a cluster so that they serve as a measure for only one indicator) is a generalized and inevitable procedure when the number of indicators and constructs is relatively high. On the other hand, the use of composites when compared with the use of individual items has associated advantages in terms of reduction of measurement error (greater reliability) and parsimony level (Grapentine, 1995; Hair et al., 1998). Thus, the items corresponding to the same cluster, which demonstrate to form a one-dimensional set, result in a composite that will be used in the analysis of the structural model (Baumgartner & Homburg, 1996; Hair et al., 1998). It should be noted that the measurement error of the dynamic capacities and export performance constructs was set to the value of [(1−Cronbach's alpha)×variance of the indicator], because they are presented with only one indicator or cluster (Bagozzi & Heatherton, 1994). In constructs with more than one indicator (entrepreneurial orientation and intangible resources), only one connection was established. This procedure, according to Diamantopoulos and Siguaw (2000), does not affect the results of the data analysis. Thus, the analysis of the parameters confirm the fitness of the model (χ2(141)=250.56, p<0.05, CFI=0.99, GFI=0.91, NNFI=0.98, RMSEA=0.054). Table 3 presents the parameter estimates of the structural model allowing the testing of the hypotheses and in Table 4 the means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented.

Hypotheses testing results.

| Parameters | Standardized coefficients | t value | R2 | Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial resources – Dynamic capabilities | 0.18 | 3.11** | H1 | Supported | |

| Informational resources – Dynamic capabilities | 0.38 | 6.06* | H2 | Supported | |

| Relational resources – Dynamic capabilities | 0.32 | 4.71* | 0.50 | H3 | Supported |

| Dynamic capabilities – Export performance | 0.29 | 4.76* | H4 | Supported | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation – Export performance | 0.44 | 5.60* | 0.35 | H5 | Supported |

Note: (*) Sig. value p<0.001; (**) Sig. value p<0.01.

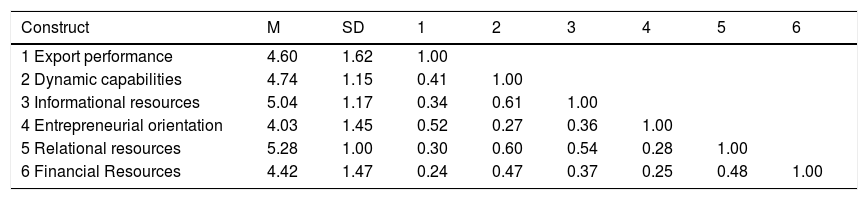

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

| Construct | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Export performance | 4.60 | 1.62 | 1.00 | |||||

| 2 Dynamic capabilities | 4.74 | 1.15 | 0.41 | 1.00 | ||||

| 3 Informational resources | 5.04 | 1.17 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 1.00 | |||

| 4 Entrepreneurial orientation | 4.03 | 1.45 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 1.00 | ||

| 5 Relational resources | 5.28 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 1.00 | |

| 6 Financial Resources | 4.42 | 1.47 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 1.00 |

Note: All correlations are significant at the 0.05 level.

Results indicate that: (1) the presence of intangible resources (financial, informational and relational resources) are important factors in the development of dynamic capabilities; (2) that dynamic capabilities have a positive impact in export performance; and (3) that entrepreneurial orientation positively enhances export performance.

The significance of the mediating effect was tested using Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). This test, considered valid for test the statistical significance of the indirect effects, is widely used in recent research (Parawansa & Anggraece, 2018; Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Yunis, El-Kassar, & Tarhini, 2017). Results confirm that intangible resources have a significant indirect impact in export performance through dynamic capabilities. The indirect effect of financial, informational and relational resources in export performance through dynamic capabilities is 0.05 (0.18×0.29; p<0.05; Z=2.41), 0.11 (0.38×0.29; p<0.01; Z=4.17), and 0.09 (0.32×0.29; p<0.01; Z=3.17), respectively. This means that intangible resources do not directly influence export performance but only through the dynamics capabilities, i.e. the impact of intangible resources is fully mediated by dynamic capabilities.

We conclude also that intangible resources and entrepreneurial orientation justified 85% of export performance (R2=35% and R2=50%, respectively).

Discussion and conclusionsThis study aims to investigate how intangible resources, dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation impact export performance. We develop and test a model according to which intangible resources (financial, informational and relational resources) have a positive and direct influence in the development of dynamic capabilities, which in turn impact export performance. In addition, the framework proposes that entrepreneurial orientation positively and directly enhances export performance.

Based on the results to an online questionnaire for top managers of a significant number of exporting firms, we validated all direct relationships of the model. Specifically, H1, H2 and H3 referring to access to financial, informational and relational resources respectively, were supported. This finding suggests that intangible resources contribute to the development of dynamic capabilities. These results are consistent with previous studies in this area which argued for the proposition that resources are antecedents of the development of capabilities (e.g. Lin & Wu, 2014; Morgan et al., 2004; Wu, 2006; Wu & Wang, 2007). These results also empirically validate Morgan et al.’s (2004) argument that resources and capabilities are interrelated.

Our findings also support H4, relative to the impact of dynamic capabilities in performance. In addition, we confirmed the mediating role of dynamic capabilities in the resources-export performance relationship. The influence of dynamic capabilities in export performance is consistent with the results of Wu (2006), Wu and Wang (2007) who studied the internal market performance of technological companies and of Lin and Wu (2014). Specifically, this finding lends credence to the idea that “dynamic capabilities are regarded as a transformer for converting resources into improved performance” (Lin & Wu, 2014, p. 407). This is a central tenet of the DCV, which holds that dynamic capabilities have a transformative role in converting resources into enhanced performance (Lin & Wu, 2014; Wu and Wang, 2007). The explaining power of the DCV, in comparison to the RBV, as been emphasized specially in dynamic and fast changing environments. Our study finds support for the view that resources can be converted into performance through dynamic capabilities in the context of volatile environment of international markets.

Finally, H5, referring to the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on export performance, was also supported. The impact of entrepreneurial orientation in performance is consistent with a large number of studies (e.g. Covin & Slevin, 1989; Covin, Slevin, & Covin, 1990; Kantur, 2016; Kollmann & Stöckmann, 2014; Miller, 1983; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). In fact, the impact of entrepreneurial on organizational performance has been well-established in the literature, however, this link has not been much studied in the context of internationalization.

Our study makes several theoretical and empirical contributions. First, our results are relevant to the DCV literature as they support the theory that capabilities can boost performance by leveraging the impact of resources. We have focused on the intangible resources of access to financial, informational and relational resources and findings show that these resources contribute to the development of dynamic capabilities. Second, we have found support for the impact of entrepreneurial orientation in export performance. Entrepreneurial orientation may be seen as a specific dynamic capability to identify venture opportunities and deploy resources (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001). More importantly, our study provides support for these tenets in the context of international markets.

Relevant practical implications are also to be noted, starting forthwith the contribution for the (re)definition of government policies supporting the adoption of strategies leading to enhanced performance through different dedicated programs, including economic and fiscal benefits. In particular, these programs may be more effective it they target the development of capabilities rather than solely access to resources.

This research has a number of limitations. First of all, there are limitations derived from the potential bias caused by the sample size and measurement. In this research, in line with previous studies, we used Likert scales 1–7 to evaluate the constructs, thus the majority of the answers are based on the subjective judgment of the respondents. Although a strong use of subjective measures to assess the performance of exports has been identified in previous studies, some responses may not reflect the actual situation of the studied variables. Additionally, although email is a commonly used tool, we cannot generalize the results to the total population. Is also important to acknowledge that the study ignores the moderating effects of some variables (e.g. hostile external environment) as well the effect of control variables, such as firm size and demographic characteristics of the respondents, which could lead to further insights. It may also be argued that evaluating the different variables in this study based on the opinion of one respondent per firm may not accurately reflect the reality of companies, as especially in large companies, in which more than one person, make decisions, and may have different opinions on the export activity (Leonidou & Katsikeas, 1996). Dealing with each of these limitations provides directions for further research.

In broad terms, the results of our study stress the importance of dynamic capabilities, which play a catalyst role in the relationship between intangible resources and export performance, contributing to filling the gaps identified by Sousa et al. (2008) regarding the need for export performance studies that consider the (direct, indirect and total) effects of mediating variables. This conclusion partly validates criticisms to the limitations of the RBV to explain firm's competitiveness, specially in volatile environments (Lin & Wu, 2014). In fact, without the ability to achieve new resource configurations as environmental conditions shift (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000), resources are clearly insufficient conditions for competitive advantage. A clear understanding of how companies develop differentiated dynamic capabilities is paramount for managers, public bodies and researchers aiming at contributing for or firms’ competitiveness and performance.