The prosumer concept has become increasingly relevant in the current economy, necessitating the development of resilient and adaptive business models. Given the lack of a systematic framework for evaluating prosumers, the present study aimed to develop a framework of reference for assessing the roles and impacts of prosumers across various industries. Although this is not a systematic literature review, 2,500 papers were initially retrieved from the Web of Science and Scopus databases, and 67 were selected and used in the prosumer conceptualisation. CiteSpace software was used to map the prosumer literature stream. The content analysis informed the exploration of the origins of the prosumer concept and the development of a contemporary definition of this concept. Terms that relate to and/or overlap with the prosumer concept, as well as the nuances of prosumer engagement levels, were also analysed. Additionally, prosumers’ place in the archetypal sharing economy, as well as their limitations and challenges, were examined. Notably, this study proposes a tentative framework of reference for prosumer conceptualisation and opens up new areas for exploration via a theory-based agenda for future research. This research offers unique contributions to the prosumer literature, practice and other related works because it comprehensively encapsulates and summarises all relevant literature pertaining to the prosumer concept and establishes a transdisciplinary conceptualisation and framework of reference.

Toffler (1980) coined the term ‘prosumer’ to describe the merging of the roles of producer and consumer into a hybrid entity capable of engaging in production and consumption. Toffler (1980) predicted that technological advancements, such as home computers and emerging communication networks, would enable individuals to produce goods and services, dissolving the traditional boundaries between producers and consumers. Thus, Toffler (1980, p. 267) suggested that ‘the distinction between producer and consumer will fade, leading to the rise of the prosumer.’

Over the decades, the prosumer concept has evolved due to rapid technological advancements, shifts in consumer behaviour and new economic theories (Kotler et al., 1986; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). The digital revolution has played a pivotal role in this transformation. The Internet and social media platforms have allowed prosumers to become increasingly engaged in the economy, shifting from passive consumers to active participants and contributors (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). Although this evolution and the contributions of prosumers are evident across various sectors of society, a new term or an updated definition that includes prosumers’ diverse activities has not been established. As a result, there are fragmented understandings among researchers and inconsistent approaches to the study of prosumers (Comor, 2011).

Given the growing importance of prosumers in an economy that removes boundaries between buyers and producers/sellers (e.g., Poshmark), a comprehensive framework that accounts for sector-specific dynamics and varying degrees of prosumer engagement and contribution is needed to systematically evaluate those prosumers’ roles. The creation of a prosumer framework of reference constitutes a key contribution of this paper to the marketing field by providing a structured method for measuring and analysing the impact of prosumers’ activities (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). Marketers could use the framework proposed in the present study to assess prosumers’ contributions in terms of value creation, engagement and behavior. Understanding the prosumer phenomenon can help businesses adjust their marketing strategies to better engage these active consumers and foster greater innovation and customer loyalty (Pienkowski, 2021).

The overall research objective (ORO) of this study is to provide a framework of reference for the prosumer concept. The specific research objectives (SRO) are as follows:

- •

SRO1: To summarise the historical development of the prosumer concept

- •

SRO2: To develop a contemporary definition and conceptualisation of the prosumer concept

- •

SRO3: To explore the boundaries and commonalities of the prosumer concept to determine how the prosumer overlaps with consumption-related concepts

- •

SRO4: To identify prosumer roles across a wide range of industries and areas

- •

SRO5: To determine the prosumer's different levels of engagement and commitment to prosumption

The major differences between this work and previous prosumer research are that the present study conducted an in-depth review of all the relevant literature on prosumers and developed a comprehensive evaluation framework. As a conceptual work, this study has important implications for theory and practice. Drawing on several decades of prosumer research, it traces the historical evolution of the prosumer concept, offers a structured approach for exploring the roles of prosumers in imperfect markets, across sectors and industries, while providing the foundations for developing prosumer measurement scales and indices for and modelling in future research. It also describes the critical features of prosumers and proposes a comprehensive conceptualisation. As a cross-disciplinary discussion, this study recasts the prosumer notion in terms of the broader discourse on contemporary challenges related to socioeconomic innovation, technological advances and sustainability imperatives.

The theoretical refinements of the prosumer concept offered in this study have implications for managerial action because they demonstrate the untapped potential of prosumer-related value creation as well as the host of business model innovations that have resulted from the acknowledgement of individuals’ ‘provision pole’ (Ertz & Sarigöllü, 2019). Specifically, businesses selling to individuals could think deeply about harnessing individuals’ ‘provision poles’ to increase the range and variety of those businesses’ offers or derive commissions from the individuals’ provision of goods or services. The proposed framework could serve as a key tool for marketers to assess prosumers’ contributions in terms of value creation, engagement and behavior, helping them quantify and leverage prosumers’ contributions and enabling them to design targeted marketing strategies that enhance prosumer engagement, foster innovation and ultimately create more resilient and adaptive organisational models.

Fig. 1 provides a roadmap for the remainder of this paper and illustrates the relationships between the topics covered. Section 2 discusses the methodology used in this paper and provides a snapshot of the prosumer literature, including visual representations developed using CiteSpace software. Section 3 delves into the origins of the prosumer concept by providing a historical overview of its evolution over more than four decades and a contemporary definition. Section 4 explores prosumers’ roles in the economy, conceptual boundaries between the prosumer concept and overlapping terms as well as the different levels of involvement and commitment encapsulated in the prosumer term. Section 5 provides an in-depth exploration of the connection between prosumers and the sharing economy and their place within the broader platform/digital economy ecosystem. It also shows that the prosumer concept remains fraught with challenges and issues. Section 6 describes the proposed framework, which considers prosumers’ development stages, identifies their economic contributions and quantifies their potential for future growth. Section 7 provides a theory-based agenda for future research consisting of several proposed research projects. Section 8 concludes the paper.

Materials and methodsWe use 1980 as the start year of the extraction since in this year, Toffler's (1980) foundational book, was published. A total of 2500 publications across various domains were identified from the Web of Science and Scopus databases. For breadth and depth, we considered scientific papers, conference proceedings, book chapters, books, professional articles, as well as master's and doctoral theses. Besides, despite inevitable duplicate issues, combining both Scopus and Web of Science databases has yielded superior corpus quality in past research (Ertz & Leblanc-Proulx, 2018), and we thus used both to extract relevant publications. All publications were screened using the following inclusion criterion: they had to mention the term ‘prosumer” either in the title, abstract or keywords fields or refer to the prosumer meaningfully and centrally throughout the text. A second round of review consisted of a more thorough examination of each paper, especially those that did not mention the ‘prosumer’ term in the title, abstract or keywords. A total of 67 papers were finally selected for analysis based on the above-mentioned inclusion criterion.

Descriptive analysesAs shown in Fig. 2, the CiteSpace visualisation revealed that the primary research areas mentioning the prosumer relate predominantly to energy, such as energy storage and sharing, transactive energy, or energy management. Closely related areas include photovoltaic systems or distribution networks and, to a lesser extent, uncertainty analysis. Other areas include social media, the sharing economy, consumption and Web 2.0.

Fig. 3 show more precisely that the emergence of the prosumer concept seems more recent in energy-related research areas, whereas it has been discussed for a longer period of time in the marketing area, notably in the domain of consumption, and of the sharing economy, but also in social media.

The emphasis of marketing on the prosumer concept in the realm of consumption is not so surprising. Unlike traditional consumers, prosumers actively participate in creating and improving products and services, often collaborating with peers and organisations (Kostakis et al., 2021; Powell & Snellman, 2004). Kotler et al. (1986) suggested that prosumers create and deliver goods and services, actively contributing to the value chain. Likewise, the rise of the prosumer is tightly associated with the emergence of social media and Web 2.0 because, in the 2000s, interactive platforms facilitating user-generated content (UGC), such as YouTube and Wikipedia, allowed consumers to become content creators. This era marked a shift from passive consumption to active production and engagement, influencing industries such as media and retail (Lang et al., 2021; Pienkowski, 2021). Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010) described prosumers as participants in digital media creation, highlighting the transformative impact of Internet technologies on consumer behaviour. The sharing economy drew largely on that technological shift by extending the creation and sharing of UGC to physical goods and services.

History of the prosumer conceptOrigins and early definitionsThe 1980s marked the beginning of a significant change in how production and consumption were viewed. Toffler's (1980) description of the prosumer concept suggested a shift from centralised mass production to personalised and decentralised production methods. In this context, a prosumer was seen as someone who produced goods for personal use or community exchange, fostering a participatory economy. Toffler (1980) also predicted that prosumers would emerge in sectors ranging from home-based manufacturing to personalised services, which would fundamentally alter traditional economic models by empowering individuals to become producers and consumers of customised products as well as drive innovation and economic diversification.

As the prosumer concept evolved across different domains from energy to agriculture, including fashion, it became clear that prosumers were not just consumers who occasionally produced goods. This change was facilitated by the rise of digital technologies, which allowed individuals to create, modify and share products and services more efficiently as well as engage in production activities that were previously limited to large organisations. The Internet played a significant role in this evolution, providing a platform for prosumers to connect, collaborate and distribute their creations globally. The ability to reach a broader audience and collaborate with others further fuelled the growth of the prosumer movement, making it a vital component of the economy (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

Development and evolutionThe evolution of the prosumer concept reflects broader societal and technological shifts, highlighting the increasing importance of prosumers in shaping economic and social landscapes. Initially focused on self-sufficiency and localised production, the term has expanded to include various activities facilitated by digital technologies. This progression highlights the increasing importance of prosumers in shaping economic and social landscapes. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of how various authors have defined, interpreted and expanded this term over time.

Definitions of prosumers.

| Year | Author(s) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Toffler | [Prosumers are] individuals who produce goods and services for their own consumption. |

| 1986 | Kotler | Prosumers are those who produce some of their own goods and services. |

| 2008 | Islas-Carmona (2008) | Prosumers have begun to assume leadership roles in the so-called network society [… which is] possible thanks to the formidable convening capacity that some prosumers have achieved. |

| 2008 | Xie et al. (2008) | Prosumers engage in value creation activities that result in the production of products they eventually consume and that become their consumption experiences. |

| 2010 | Ritzer et al. (2010) | Prosumers engage in both the production and consumption of goods, contributing to the economic process by creating value. |

| 2012 | Sánchez Carrero and Contreras Pulido (2012) | Prosumers are people who produce content in function of their needs as consumers, modifying [their] work habits and [the] conditions of a volatile economy as productions would be renewed based on supply and demand. |

| 2008 | Giurgiu and Barsan (2008) | Prosumers are figures that have emerged most strongly in the world of Web 2.0, referring to users who create their content self-sufficiently, without intermediaries, but with various tools capable of solving their own needs. |

| 2013 | Fox et al. | Health prosumers are individuals who manage their own health data and participate in the creation and sharing of health information. |

| 2016 | Miranda Galbe and Figuero Espadas (2016) | Prosumers are a community that seek each other out, hold meetings and formulate questions through which they deepen the stories of which they are fans. |

| 2016 | Kotilainen et al. (2016) | Prosumers are consumers who also produce their own energy, typically through residential solar photovoltaic systems, and who can actively participate in the energy market. |

| 2021 | Lang et al. | Prosumers are individuals who consume and produce value, either for self-consumption or consumption by others, and [they] can receive implicit or explicit incentives from organisations involved in the exchange. |

| 2023 | Kraus et al. (2023) | Prosumers are individuals or entities that consume and produce goods or services, actively participating in the value creation process within circular economy frameworks. |

| 2024 | Leal Filho et al. | Energy prosumers produce and consume energy, and [they] can provide [a] demand response and other energy services to the power system. |

Note: This table contains all the unique definitions provided in the 67 papers included in this study.

During the 1990s, the term ‘prosumer’ was not prominently discussed in scientific studies, possibly due to limited access to digital technologies, and thus a limited deployment of the prosumer and a lack of recognition of the concept's broader economic implications. In other words, since the Internet and personal computing were in their infancy; these technological advancements were not yet widespread or accessible to the general population. As a result, the prosumer concept did not gain significant academic or practical traction during this period.

The 2000s saw a resurgence of interest, particularly with the rise of digital platforms and Web 2.0, which refers to the interactive capabilities of the Internet. Tapscott and Williams (2008) emphasised the role of prosumers in the digital age, describing them as active participants in digital media creation. Xie et al. (2008, p. 2) defined prosumption as ‘value creation activities undertaken by the consumer that result in the creation of their own products and services rather than the use of final or customised propositions from the marketplace’. This definition reflects a modern understanding of the collaborative efforts of prosumers in designing and producing goods and services. Although not mentioned in that definition, prosumption, in this context, occurs likely through the use of supportive communication technologies, and emphasizes prosumers’ contributions to innovation and economic growth.

Technological advancements have further diversified the roles of prosumers. According to Kotilainen (2019), prosumers contribute to sustainability and innovation in decentralised energy production by generating their own renewable energy. Parra-Dominguez et al. (2023) discussed how prosumers impact Mediterranean viticulture socioecological systems by integrating the production and consumption of renewable energy into their agricultural practices. Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010) described prosumers in the digital media landscape as individuals who produce and consume content, particularly via Web 2.0 and social media platforms. They argued that, in the digital realm, ‘the lines between producer and consumer have become increasingly blurred’ due to the rise of prosumption (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010, p. 25).

Contemporary definition of prosumersContemporary prosumers are crucial economic players, driving innovation, sustainability and collaboration and creating value for themselves and society (Leal et al., 2024; Pienkowski, 2021). Given the dynamic nature of prosumers and their impact on various sectors, researchers agree on the need for a modern definition of prosumers that encapsulates their essence and accurately reflects their multifaceted roles in today's economy (Lang et al., 2021; Pienkowski, 2021; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). Therefore, based on an analysis of historical and contemporary perspectives, the following definition is proposed : Prosumers create value for themselves and others independently or in collaboration with organisations, communities or peers.

Value creation in the prosumer contextValue creation refers to the generation of benefits that enhance the well-being of individuals or communities. The phrase ‘create value for themselves and others’ was included in the definition above to emphasise the dual impact of prosumer activities. Prosumers create value by contributing to product and service development, improvement and/or innovation (Lang et al., 2021; Pienkowski, 2021). The more immersed individuals are in such contributions, the greater the potential value they add. Value creation is central to prosumerism because it encompasses the tangible and intangible benefits of active participation in production processes. Economic benefits include cost savings and revenue generation, and social benefits include community development while environmental benefits include sustainability (Leal et al., 2024).

In the agricultural sector, prosumers produce and consume their harvests. Their involvement in the cultivation, maintenance and consumption of crops exemplifies how immersive participation leads to significant value creation (Jain & Potdar, 2021). In the digital economy, prosumers create value by generating content, providing feedback and participating in collaborative innovation. Platforms such as YouTube and Wikipedia and open-source software communities rely heavily on prosumer contributions. For example, YouTube creators generate content that attracts viewers, advertisers and revenue, creating a value cycle that benefits the creators and the platform (Tapscott & Williams, 2008).

In the renewable energy sector, prosumers who generate energy through solar panels or wind turbines not only reduce their energy costs but also contribute excess energy to the grid, enhancing the overall energy infrastructure. This type of value creation promotes sustainability and resilience in energy systems (Kotilainen, 2019; Parra-Dominguez et al., 2023). In the sharing economy, prosumers participating in platforms such as Airbnb and Uber create value by offering services or properties to others, fostering a collaborative economic environment. Their active participation helps build trust, improve services and drive economic growth in the sharing economy (Kotler et al., 1986).

Collaborative nature of prosumer activitiesThe collaborative nature of prosumer activities is a crucial aspect of value creation. Prosumers often work with businesses, communities and other individuals to drive innovation and continuous improvement. This collaboration can lead to the development of new products, the enhancement of existing services and the creation of new markets. Prosumers’ feedback and insights are invaluable for businesses seeking to stay competitive and responsive to consumer needs (Lang et al., 2021; Ritzer, 2010). For example, technology companies often engage with prosumers to beta-test new products, gather user feedback and make iterative improvements. This collaborative process ensures that the final product meets users’ needs and expectations, increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty (Pienkowski, 2021; Ritzer, 2010).

Roles of prosumers in the economyThis section offers a conceptual analysis of the prosumer concept and synthesises previous research on prosumers in various fields. It also describes the conceptual framework, which was developed to clarify prosumers’ roles and level of engagement in various prosumer activities.

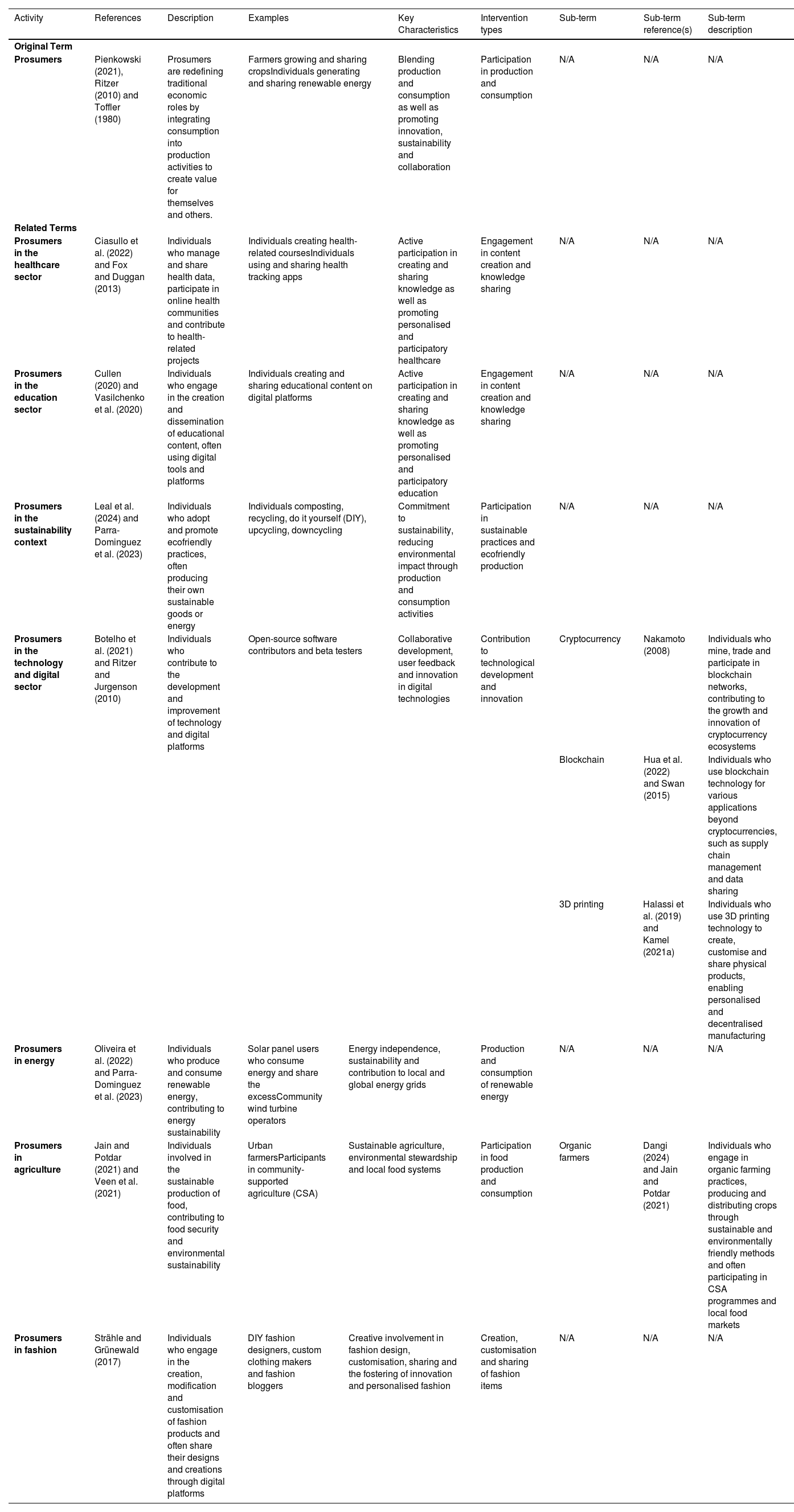

Conceptual analysis of the prosumer conceptTable 2 presents a synthesis of terms in the literature that refer directly to the prosumer and its adaptation across different sectors. Table 2 also summarizes terms that overlap with prosumerism. As shown in Table 2, prosumers are actively involved in all aspects of production and consumption. The roles of prosumers are particularly pronounced in sectors such as technology, sustainability, healthcare and education and the sharing economy. Their involvement in these areas highlights the transformative potential of prosumption, where the traditional consumer role is augmented by creative and productive contributions that benefit individuals and society at large (Kotler et al., 1986; Cullen, 2020; Vasilchenko et al., 2020; Leal et al., 2024; Parra-Dominguez et al., 2023; Vasilchenko et al., 2020). The subsections below discuss the roles of prosumers in specific sectors as well as the roles of producers and consumers in activities that involve terms that overlap with the prosumer concept.

Distinctions and frontiers of the prosumer concept.

| Activity | References | Description | Examples | Key Characteristics | Intervention types | Sub-term | Sub-term reference(s) | Sub-term description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Term | |||||||||||

| Prosumers | Pienkowski (2021), Ritzer (2010) and Toffler (1980) | Prosumers are redefining traditional economic roles by integrating consumption into production activities to create value for themselves and others. | Farmers growing and sharing cropsIndividuals generating and sharing renewable energy | Blending production and consumption as well as promoting innovation, sustainability and collaboration | Participation in production and consumption | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Related Terms | |||||||||||

| Prosumers in the healthcare sector | Ciasullo et al. (2022) and Fox and Duggan (2013) | Individuals who manage and share health data, participate in online health communities and contribute to health-related projects | Individuals creating health-related coursesIndividuals using and sharing health tracking apps | Active participation in creating and sharing knowledge as well as promoting personalised and participatory healthcare | Engagement in content creation and knowledge sharing | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Prosumers in the education sector | Cullen (2020) and Vasilchenko et al. (2020) | Individuals who engage in the creation and dissemination of educational content, often using digital tools and platforms | Individuals creating and sharing educational content on digital platforms | Active participation in creating and sharing knowledge as well as promoting personalised and participatory education | Engagement in content creation and knowledge sharing | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Prosumers in the sustainability context | Leal et al. (2024) and Parra-Dominguez et al. (2023) | Individuals who adopt and promote ecofriendly practices, often producing their own sustainable goods or energy | Individuals composting, recycling, do it yourself (DIY), upcycling, downcycling | Commitment to sustainability, reducing environmental impact through production and consumption activities | Participation in sustainable practices and ecofriendly production | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Prosumers in the technology and digital sector | Botelho et al. (2021) and Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010) | Individuals who contribute to the development and improvement of technology and digital platforms | Open-source software contributors and beta testers | Collaborative development, user feedback and innovation in digital technologies | Contribution to technological development and innovation | Cryptocurrency | Nakamoto (2008) | Individuals who mine, trade and participate in blockchain networks, contributing to the growth and innovation of cryptocurrency ecosystems | |||

| Blockchain | Hua et al. (2022) and Swan (2015) | Individuals who use blockchain technology for various applications beyond cryptocurrencies, such as supply chain management and data sharing | |||||||||

| 3D printing | Halassi et al. (2019) and Kamel (2021a) | Individuals who use 3D printing technology to create, customise and share physical products, enabling personalised and decentralised manufacturing | |||||||||

| Prosumers in energy | Oliveira et al. (2022) and Parra-Dominguez et al. (2023) | Individuals who produce and consume renewable energy, contributing to energy sustainability | Solar panel users who consume energy and share the excessCommunity wind turbine operators | Energy independence, sustainability and contribution to local and global energy grids | Production and consumption of renewable energy | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Prosumers in agriculture | Jain and Potdar (2021) and Veen et al. (2021) | Individuals involved in the sustainable production of food, contributing to food security and environmental sustainability | Urban farmersParticipants in community-supported agriculture (CSA) | Sustainable agriculture, environmental stewardship and local food systems | Participation in food production and consumption | Organic farmers | Dangi (2024) and Jain and Potdar (2021) | Individuals who engage in organic farming practices, producing and distributing crops through sustainable and environmentally friendly methods and often participating in CSA programmes and local food markets | |||

| Prosumers in fashion | Strähle and Grünewald (2017) | Individuals who engage in the creation, modification and customisation of fashion products and often share their designs and creations through digital platforms | DIY fashion designers, custom clothing makers and fashion bloggers | Creative involvement in fashion design, customisation, sharing and the fostering of innovation and personalised fashion | Creation, customisation and sharing of fashion items | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

Prosumers in the healthcare sector actively manage and share their health data, participate in online health communities and contribute to health-related projects. Their active participation in the healthcare sector promotes personalised and participatory healthcare services, improving health outcomes and fostering innovation in medical practices (Ciasullo et al., 2022). However, it also raises concerns about data privacy and the accuracy of self-reported health information. Proper regulation and reliable platforms are essential to mitigate these risks (Ciasullo et al., 2022; Fox & Duggan, 2013). In addition, the integration of UGC into professional healthcare systems can lead to more comprehensive and personalised care but requires careful management to ensure data accuracy and patient confidentiality (Ciasullo et al., 2022).

Prosumers in the education sectorProsumers in the education sector utilise digital tools and platforms to create and disseminate educational content, which promotes personalised and participatory education, enhances learning experiences and broadens access to knowledge (Vasilchenko et al., 2020). Furthermore, integrating UGC into formal education can foster a more engaging and interactive learning environment (Cullen, 2020). Prosumers’ involvement in education democratises knowledge but presents challenges in terms of ensuring content quality and intellectual property rights. Effective moderation and open access policies are crucial for maximising benefits while minimising drawbacks (Vasilchenko et al., 2020).

Prosumers in the sustainability contextProsumers in the sustainability context adopt and promote eco-friendly practices, often producing their own sustainable goods or energy (Leal et al., 2024; Parra-Dominguez et al., 2023). They play a crucial role in reducing environmental impact through composting, recycling and upcycling (Leal et al., 2024). This commitment to sustainability drives innovation and supports the transition to a more sustainable economy. However, the scalability of these practices and their integration into larger systems remain significant challenges that need to be addressed through supportive policies and technologies (Leal et al., 2024; Parra-Dominguez et al., 2023). The role of prosumers in sustainability is particularly important in promoting decentralised and community-based approaches to environmental stewardship (Leal et al., 2024).

Prosumers in the technology and digital sectorProsumers contribute significantly to the development and improvement of technologies and digital platforms (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). They serve as open-source software contributors and beta testers, which fosters collaborative development and innovation and is crucial for technological advancement and the continuous improvement of digital tools (Botelho et al., 2021). Furthermore, their active involvement in technology development can accelerate innovation cycles and improve product relevance (Botelho et al., 2021). Despite their contributions, prosumers in this field often face issues related to intellectual property rights and the recognition of their work. Therefore, clear guidelines and equitable reward systems must be established to sustain their engagement (Botelho et al., 2021; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

Prosumers have made significant contributions to cryptocurrency, blockchain and three-dimensional (3D) printing technologies. Regarding cryptocurrency, individuals who mine, trade and participate in blockchain networks contribute to the growth and innovation of cryptocurrency ecosystems (Nakamoto, 2008). Although they drive innovation and decentralisation in financial systems, prosumers may face significant regulatory scrutiny and environmental concerns related to the high energy consumption of mining activities (Nakamoto, 2008).

Prosumers who utilise blockchain technology for applications beyond cryptocurrency, such as supply chain management and data sharing, can enhance the transparency and security of various industries (Hua et al., 2022; Swan, 2015). However, the complexity of blockchain technology and the need for regulatory frameworks pose challenges (Hua et al., 2022; Swan, 2015).

Individuals who use 3D printing technology to create, customise and share physical products enable personalised and decentralised manufacturing (Halassi et al., 2019; Kamel, 2021b). This decentralisation process democratises production but raises concerns about intellectual property and the environmental impact of widespread plastic use (Halassi et al., 2019).

Prosumers in the energy sectorProsumers in the energy sector produce and consume renewable energy, contributing to energy sustainability (Oliveira et al., 2022; Parra-Dominguez et al., 2023). They achieve energy independence and promote environmental sustainability by generating their own energy and sharing the excess with the grid. This decentralised energy production supports the resilience and sustainability of the energy system but requires substantial initial investments and a supportive infrastructure. Incentive programmes and grid modernisation are crucial for maximising the benefits of prosumer participation in this sector (Kotilainen, 2019; Oliveira et al., 2022). Moreover, the integration of prosumers into energy markets can enhance grid stability and promote the adoption of renewable energy sources (Oliveira et al., 2022).

Prosumers in the agricultural sectorProsumers involved in the agricultural sector contribute to food security and environmental sustainability through sustainable practices (Jain & Potdar, 2021; Veen et al., 2021). They engage in urban farming and community-supported agriculture (CSA), promoting local food systems, locavorism and environmental stewardship (Dangi, 2024; Jain & Potdar, 2021). These practices support environmental sustainability and health but require significant knowledge and effort. Furthermore, market demand and certification processes can be challenging (Jain & Potdar, 2021). Although the growing consumer demand for organic products supports the expansion of organic farming, rigorous standards and practices are needed (Dangi, 2024). Hence, even though these practices can enhance local food security and reduce carbon footprints, prosumers may face scalability and market integration challenges. Policy support and community initiatives are key to overcoming these barriers (Jain & Potdar, 2021; Veen et al., 2021). The role of prosumers in local food systems is vital for promoting resilience and reducing dependency on industrial agriculture (Jain & Potdar, 2021).

Prosumers in the fashion sectorProsumers in the fashion sector are involved in the creation, modification and customisation of fashion products, often sharing their designs and creations through digital platforms (Strähle & Grünewald, 2017). These creative activities foster innovation and personalised fashion, allowing individuals to express their unique styles. Besides, the rise of do-it-yourself (DIY) fashion and digital platforms has enabled prosumers to influence trends and challenge traditional fashion paradigms (Strähle and Grünewald (2017).

Terms that overlap with the ‘Prosumer’ conceptTable 3 presents a synthesis of terms in the literature that overlap with prosumerism. The subsections below discuss the roles of producers and consumers in activities that involve terms that overlap with the prosumer concept.

Terms that overlap with the prosumer concept.

| Term | Reference(s) | Description | Example(s) | Key Characteristics | Intervention types | Sub-term | Sub-term reference(s) | Sub-term description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlapping Terms | ||||||||||

| UGC creators | Halliday (2016) and Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010) | Individuals who produce content such as videos, articles and social media posts, which they typically share on digital platforms | YouTube creators, Wikipedia editors and social media users | Create and share digital content and influence cultural and digital landscapes | Creation and sharing of digital content | Influencers | Brown and Hayes (2008) and Himelboim and Golan (2019) | Social media personalities who influence purchasing decisions through endorsements and content creation | ||

| Peer producers | Kostakis et al. (2021) and Powell and Snellman (2004) | Collaborative production of goods or services through open-source or commons-based projects | ||||||||

| Makers and DIY enthusiasts | Anderson (2012) | Creating, modifying or repairing items as a hobby or for personal use and often sharing projects online | ||||||||

| Microentrepreneurs | Gržanić et al. (2022) and Tapscott and Williams (2008) | Individuals who start small organisations or side gigs and often leverage digital platforms to sell products or services | Etsy sellers, eBay resellers and Shopify store owners | Entrepreneurial activity, leveraging digital marketplaces and individual production | Entrepreneurial activity and individual production | Digital entrepreneurs | Rayna (2021) and Tapscott and Williams (2008) | Peer marketplaces, drop shipping, trading, affiliate marketing, forex and more, leveraging digital platforms for various entrepreneurial activities | ||

| Collaborative consumers | Ertz et al. (2019) and Giglio et al. (2023) | Individuals who share access to goods and services, participating in the collaborative economy and sharing economy through platforms such as Airbnb and Uber | Airbnb hosts, Uber drivers and TaskRabbit workers | Peer-to-peer sharing, access over ownership and collaborative consumption | Collaborative consumption and resource sharing | Redistribution | Botsman and Rogers (2010) | The offering of goods directly to others through digital platforms, facilitating peer-to-peer exchanges without traditional intermediaries | ||

| Mutualisation | Humpez (2022) | The practice of sharing resources among individuals to maximise their utility and minimise costs | ||||||||

| Gig economy | Anwar and Graham (2020) and Castillo-Villar et al. (2024) | The provision of temporary flexible jobs, often facilitated through digital platforms | ||||||||

| Co-creators | Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004) and Ramaswamy and Gouillart (2010) | Individuals who work collaboratively with other individuals, organisations or communities to design and develop products and services | Participants in design sprints, innovation workshops or community-led urban planning projects | Focuses on collaborative development, user involvement and feedback | Collaborative development and user involvement | Open innovation | Füller (2006) | Consumers are deeply involved in all phases of product creation, from idea generation to testing. This engagement helps incorporate diverse perspectives and accelerates innovation cycles. | ||

| Open source | Cooke and Buckley (2008) | Innovation is driven by shared intellectual property, allowing community contributions to enhance development. Open-source projects benefit from collective intelligence and can significantly reduce development costs. | ||||||||

| Crowdsourcing | Rubel (2006) | This utilises the collective intelligence of large groups to generate solutions and new ideas as well as leveraging diverse skills and knowledge, making problem-solving more efficient and innovative. | ||||||||

| Co-communication | Muñiz and Schau (2007) | This involves a wide range of consumers in competitions to create visual images or films for advertising campaigns. | ||||||||

| Co-innovation | Cova (2008) | This cross-disciplinary approach integrates contributions from multiple sectors to create comprehensive solutions and fosters holistic and innovative outcomes. | ||||||||

| Co-ideation | Agrawal and Rahman (2015), Roser et al. (2013) and Von Hippel (2001) | This approach encourages consumers to contribute innovative ideas, supported by resources such as toolkits and software, and it democratises the innovation process and harnesses broad creativity. | ||||||||

| Co-design | Merle et al. (2008) | This involves interactions between consumers and the use of computer-assisted tools in the design process to modify and visualise product components in real time. This ensures that products are better tailored to consumer needs. | ||||||||

| Co-testing | Agrawal and Rahman (2015) | This engages consumers in testing new products before launch to gather practical feedback, which reduces market risks and helps refine products based on real-world use. | ||||||||

| Co-evaluation | Agrawal and Rahman (2015) | This involves assessing ideas provided by consumers to evaluate their feasibility and value. This process benefits from multiple perspectives, improving decision-making and innovation quality. | ||||||||

| Co-determination | Cova (2008) | This involves aligning business goals with consumer needs and feedback for mutual benefit. This alignment fosters stronger customer loyalty and satisfaction as well as a better product-market fit. | ||||||||

| Co-production | Bendapudi and Leone (2003) and Bolton and Saxena-Iyer (2009) | This entails the direct involvement of consumers in the production process to enhance service and product relevance. Companies can better meet market demands and improve product quality by integrating customer input. | ||||||||

| Experience co-creation | Rahman (2006) | This involves collaborating with customers to create richer and more engaging experiences. This process turns passive consumers into active participants, enhancing their overall experience and satisfaction. | ||||||||

| Co-promotion | Agrawal and Rahman (2015) | This involves using consumer advocacy to enhance brand reputation and extend market reach through word-of-mouth communication. This organic promotion is highly trusted and effective in expanding a brand's influence. | ||||||||

| Co-distribution | Agrawal and Rahman (2015) | Consumers are involved in the distribution process, empowering them to take an active role in the supply chain. This participation increases efficiency and customer satisfaction. | ||||||||

| Co-consumption | Agrawal and Rahman (2015) | This involves promoting the sharing of consumption experiences among consumers to build community and loyalty. This shared value enhances customer engagement and fosters a sense of belonging. | ||||||||

| (Mass) customisation | Merle (2010) | This involves allowing consumers to personalise products on a large scale, meeting individual preferences while maintaining efficiency. This customisation caters to specific consumer needs and enhances satisfaction. | ||||||||

| Participatory operations | Reniou (2009) | Consumers are directly involved in decision-making processes, such as voting on new products or participating in product castings. This engagement fosters a sense of ownership and increases product success. | ||||||||

| Self-production | Rifkin (2011)) | Consumers engage in self-production when they actively and independently create finished products, such as preparing a meal or assembling a piece of furniture, using products, tools and devices supplied by companies. | ||||||||

| Prosumption | Xie et al. (2008) | This is a set of value-creating activities that integrate the physical activity, mental effort and sociopsychological experiences undertaken by consumers, leading to the production of products that they eventually consume and which become their consumption experience. | ||||||||

UGC creators produce videos, articles and social media posts and share them on digital platforms (Halliday, 2016; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). These individuals play a significant role in shaping cultural and digital landscapes through their creative contributions, and their widespread influence highlights the importance of digital literacy and ethical guidelines (Halliday, 2016). Furthermore, content quality, intellectual property and fair compensation are critical issues that need to be addressed through platform policies and regulations (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). UGC creators include influencers, peer producers and makers and DIY enthusiasts.

Influencers are social media personalities who affect purchasing decisions through endorsements and content creation, and they play a major role in digital marketing and cultural trends (Brown & Hayes, 2008; Himelboim & Golan, 2019). Although they can drive significant economic activity, ethical concerns about transparency and the authenticity of endorsements persist. To maintain consumer trust, it is essential to ensure that influencer marketing has clear guidelines and accountability (Brown & Hayes, 2008). The power of influencers in shaping consumer behaviour necessitates responsible practices and regulatory oversight (Himelboim & Golan, 2019).

Peer producers engage in the collaborative production of goods or services through open-source or commons-based projects (Kostakis et al., 2021; Powell & Snellman, 2004). Sustaining these projects often requires a balance between volunteer contributions and professional management and funding (Powell & Snellman, 2004). The success of peer production initiatives relies on robust community engagement and sustainable funding models (Powell & Snellman, 2004).

Makers and DIY enthusiastsMakers and DIY enthusiasts represent a growing community of individuals who embody the spirit of innovation, creativity and self-sufficiency. Anderson (2012) stated that these individuals are at the forefront of a new industrial revolution, leveraging technology and open-source designs to create, modify and repair objects. As the movement evolves, it has the potential to reshape industries, educational approaches and consumer behaviour, embodying the transformative power of individual creativity and collective innovation (Anderson, 2012).

MicroentrepreneursMicroentrepreneurs start small organisations or side gigs, often leveraging digital platforms to sell their products or services (Gržanić et al., 2022; Tapscott & Williams, 2008). This type of entrepreneurial activity drives economic growth and innovation by creating new market opportunities. However, microentrepreneurs face market competition, financial stability and regulatory compliance challenges. Supportive policies and resource access are essential to sustain their ventures (Gržanić et al., 2022; Tapscott & Williams, 2008). Digital platforms provide microentrepreneurs with unprecedented opportunities but require adaptive business strategies and resilience (Tapscott & Williams, 2008).

One of the most important branches of microentrepreneurship is digital entrepreneurship. Digital entrepreneurs engage in digital marketplaces, drop shipping, trading and affiliate marketing, leveraging digital platforms for entrepreneurial activities (Rayna, 2021; Tapscott & Williams, 2008). Digital entrepreneurs drive economic growth but face challenges such as market saturation, cybersecurity risks and evolving regulatory landscapes (Tapscott & Williams, 2008). The dynamic nature of digital entrepreneurship requires continuous innovation and adaptation to market trends (Rayna, 2021; Tapscott & Williams, 2008).

Collaborative consumersCollaborative consumers share access to goods and services through platforms such as Airbnb and Uber, which promote resource optimisation (Ertz et al., 2019; Giglio et al., 2023). This model fosters economic efficiency and community building but raises issues related to regulation, taxation and the impact on traditional industries. Effective policies and platform accountability are needed to ensure sustainable growth (Ertz et al., 2019). The collaborative economy challenges conventional business models and requires new regulatory approaches to balance innovation and protection (Giglio et al., 2023). Collaborative consumers may be involved with redistribution, mutualisation and/or the gig economy.

Redistribution facilitates peer-to-peer exchanges without traditional intermediaries. It promotes resource efficiency and community engagement but requires robust systems for trust and safety (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). The success of redistribution models depends on strong community norms and reliable platforms (Botsman & Rogers, 2010).

Mutualisation involves the sharing of resources among individuals to maximise utility and minimise costs. It enhances economic efficiency and environmental sustainability but can be limited by logistical challenges and varying levels of commitment among participants (Ertz et al., 2017). Mutualisation models benefit from clear agreements and effective resource management (Ertz et al., 2017).

In a sense, the gig economy can be considered a subset of mutualisation inasmuch as individuals share resources such as their times, skills, and resources, at large, with others. In the gig economy, digital platforms facilitate the provision of jobs. This system offers economic opportunities and flexibility but presents challenges related to job security, benefits and fair compensation. To address these issues, comprehensive labour policies and platform accountability are crucial (Anwar & Graham, 2020; Castillo-Villar et al., 2024). The growth of the gig economy underscores the need for adaptable labour regulations and social protections (Anwar & Graham, 2020).

Co-CreatorsCo-creators work collaboratively with organisations and/or communities to design and develop products and services (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004; Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010). They are crucial for collaborative development and user involvement, which can enhance product relevance and market fit. However, managing intellectual property rights, ensuring equitable contribution recognition and maintaining high-quality output are ongoing challenges that need to be addressed through effective collaboration frameworks and policies (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). Co-creation includes the following segmented concepts:

- (1)

Open innovation: In open innovation, co-creators are deeply involved in all phases of product creation, from idea generation to testing. This approach enhances innovation but requires balancing openness with intellectual property protection and competitive advantage (Füller, 2006). Thus, open innovation models thrive on transparency and collaboration but must navigate intellectual property complexities (Füller, 2006).

- (2)

Open source: Open-source initiatives are driven by shared intellectual property, which enables community contributions and fosters rapid development and collaboration. The sustainability of these initiatives requires financial support and governance structures, and it depends on robust community support and effective management (Cooke & Buckley, 2008).

- (3)

Crowdsourcing: Crowdsourcing leverages collective intelligence for problem-solving and idea generation and drives innovation and efficiency. Crowdsourcing initiatives benefit from diverse inputs but require clear guidelines and oversight as well as robust management to ensure the quality and feasibility of contributions (Rubel, 2006).

- (4)

Co-communication: Co-communication strategies and practices enhance interaction and engagement between brands and consumers (Muñiz & Schau, 2007). This approach leverages UGC and social media platforms to foster a two-way communication channel, allowing consumers to contribute to and shape brand narratives. Co-communication also includes community management and participatory marketing in which consumers actively participate in brand-related discussions and content creation ((Muñiz & Schau, 2007).

- (5)

Co-innovation: Successful co-innovation depends on effective cross-sector collaboration and shared objectives (Cova, 2008). Integrating contributions from multiple sectors for comprehensive solutions promotes holistic and innovative outcomes but requires strong coordination and precise goal alignment (Cova, 2008).

- (6)

Co-ideation: Co-ideation encourages consumers to contribute innovative ideas, democratising the innovation process and harnessing broad creativity. However, resources and support are required to realise potential solutions (Roser et al., 2013; Von Hippel, 2001). Co-ideation processes thrive on inclusivity and structured facilitation (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (7)

Co-design: Interactions between consumers and the use of computer-assisted tools in a co-design process allow real-time modifications to be made to products in order to better meet consumer needs. This approach fosters user engagement but requires accessible tools and effective communication (Merle et al., 2008). Co-designing enhances product relevance but relies on collaborative design tools and processes (Merle et al., 2008).

- (8)

Co-testing: Engaging consumers in the testing of new products before a launch allows companies to obtain practical feedback that reduces market risks and improves product quality. Effective co-testing requires structured testing protocols and participant engagement (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015). Co-testing processes benefit from iterative feedback and adaptive testing frameworks (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (9)

Co-evaluation: Assessing consumer ideas for feasibility and value allows companies to benefit from multiple perspectives, improving decision-making processes and innovation quality. Effective co-evaluation processes require transparent criteria and collaborative assessment tools (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015). Co-evaluation enhances innovation outcomes through inclusive assessment practices (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (10)

Co-determination: Aligning business goals with consumer needs and feedback through co-determination yields mutual benefits and increases customer loyalty and satisfaction. This alignment requires ongoing dialogue and adaptive strategies to remain relevant (Cova, 2008). Co-determination processes benefit from continuous stakeholder engagement and responsive management (Cova, 2008).

- (11)

Co-production: The direct involvement of consumers in a co-production process enhances service and product relevance by integrating customer input. This approach improves market fit and product quality but requires effective coordination and resource allocation (Bendapudi & Leone, 2003; Bolton & Saxena-Iyer, 2009). Co-production increases consumer engagement and satisfaction (Bolton & Saxena-Iyer, 2009).

- (12)

Experience co-creation: Collaborating with customers to create richer and more engaging experiences turns passive consumers into active participants. Experience co-creation enhances brand loyalty, customer satisfaction and engagement through interactive experiences but requires careful design and facilitation (Rahman, 2006).

- (13)

Co-promotion: Co-promotion involves the use of consumer advocacy to enhance brand reputation and extend market reach through word-of-mouth communication (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015). This organic type of promotion is highly trusted and effective for expanding a brand's influence but relies on genuine consumer engagement and positive experiences (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (14)

Co-distribution: Involving consumers in a co-distribution process empowers them to take an active role in the supply chain. Co-distribution increases customer satisfaction and enhances supply chain efficiency through consumer involvement and responsive logistics (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (15)

Co-consumption: Promoting the sharing of consumption experiences among consumers builds community and loyalty. This shared value enhances customer engagement and fosters a sense of belonging but requires supportive digital platforms as well as community norms and engagement (Agrawal & Rahman, 2015).

- (16)

(Mass) customisation: Allowing consumers to personalise products on a large scale is a way to meet individual preferences while maintaining efficiency. This approach caters to specific consumer needs and enhances satisfaction but requires adaptable production systems and effective customisation tools (Merle, 2010). Mass customisation leverages flexible manufacturing and consumer preferences for personalised products (Merle, 2010).

- (17)

Participatory operations: Direct consumer involvement in decision-making processes, such as voting on new products or participating in product castings, fosters a sense of ownership and increases product success. Participatory operations enhance consumer engagement and product relevance through collaborative decision-making but require inclusive processes and transparent communication (Reniou, 2009).

- (18)

Self-production: In self-production, consumers produce goods for their own use and often utilise digital tools and platforms (Rifkin, 2011). This concept is particularly prevalent in DIY and maker movements in which individuals leverage technologies such as 3D printing, software development kits and open-source hardware to create customised products (Rifkin, 2011). Self-production empowers consumers and promotes sustainability by enabling localised and on-demand production.

- (19)

Prosumption: Consumers also act as producers, engaging in the creation, modification and distribution of goods and services (Xie et al., 2008). This concept blurs the lines between consumption and production, as individuals use digital tools and platforms to contribute to product development, customisation and even marketing. Prosumption is a driving force in the sharing economy and open-source projects in which collaborative efforts lead to innovative solutions and personalised experiences (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010; Xie et al., 2008).

The aforementioned terms were analysed to determine how they relate to the prosumer concept. Although these terms share some characteristics with the activities of prosumers, they do differ. Table 4 categorises the terms based on three levels of prosumer effort: low, medium and high. A general description of the effort levels as well as the criteria for assigning the effort levels in terms of the production and tangibility of the prosumption output are also provided.

Term categorisation based on prosumer effort levels.

| Effort Level | Term | General Description | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Tangibility | |||

| Low effort | Open innovation | These terms refer to consumer involvement that is peripheral or indirect, such as providing ideas or feedback. Direct creation and personal value generation are low in these activities | These terms reflect low effort in direct production. Contributions are primarily ideas, suggestions or feedback. | These terms reflect more intangibility. Contributions are generally intellectual or conceptual inputs rather than physical products. |

| Open source | ||||

| Co-innovation | ||||

| Experience co-creation | ||||

| Co-ideation | ||||

| Mass customisation | ||||

| Co-communication | ||||

| Medium effort | Co-design | These terms involve substantial consumer participation in creating or enhancing products and services and typically involve collaborating with companies. Although consumers contribute significantly, they do not independently produce the final product. | These terms reflect a moderate level of involvement in production and a collaborative design process. | These terms reflect a moderate level of tangibility. Contributions lead to practical improvements or refinements. |

| Mutualisation | ||||

| UGC creators | ||||

| Influencers | ||||

| Digital entrepreneurs | ||||

| Redistribution | ||||

| Microentrepreneurs | ||||

| Co-testing | ||||

| Co-evaluation | ||||

| Co-consumption | ||||

| Co-promotion | ||||

| Co-distribution | ||||

| Collaborative consumers | ||||

| Makers and DIY enthusiasts | ||||

| Blockchain | ||||

| Cryptocurrency | ||||

| Participatory operations | ||||

| Co-determination | ||||

| High effort | Co-production | These terms describe activities in which consumers are directly involved in creating or producing products and services. They closely align with the prosumer concept, emphasising individual creation and value generation. | These terms reflect a high degree of involvement in direct production. Tangible products or services are produced or co-produced. | These terms reflect a high level of tangibility. Contributions result in the creation of physical products or substantial digital outputs or process innovation. |

| 3D printing | ||||

| Peer producers | ||||

| Co-creation | ||||

| Organic farmers | ||||

| Gig economy | ||||

| Crowdsourcing | ||||

| Self-production | ||||

| Prosumption | ||||

| Prosumers in healthcare | ||||

| Prosumers in education | ||||

| Prosumers in technology and digital innovation | ||||

| Prosumers in fashion | ||||

| Prosumers in energy | ||||

| Prosumers in agriculture | ||||

| Prosumer | ||||

Seven terms – open innovation, open source, co-innovation, experience co-creation, co-ideation, mass customisation and co-communication – refer to consumer effort that is peripheral or indirect, such as providing ideas or feedback. Open innovation and open source rely on collaborative feedback and idea generation, while co-innovation invites consumer input in the early product development stages. Compared to high- and medium-effort activities, these terms reflect lower levels of direct creation and personal value generation. These terms relate to collaborative innovation but differ from the core prosumer activities of direct creation on the production criterion, since prosumption inherently involves production albeit not necessarily in tangible form.

Medium level of effortEighteen terms – co-design, mutualisation, UGC creators, influencers, digital entrepreneurs, redistribution, microentrepreneurs, co-testing, co-evaluation, co-consumption, co-promotion, co-distribution, collaborative consumers, makers and DIY enthusiasts, blockchain, cryptocurrency, participatory operations and co-determination – involve substantial consumer participation in the creation or enhancement of products and services, typically in collaboration with companies. Consumers significantly contribute to but do not independently create the final products. The gig economy and mutualisation highlight shared economic activities and resource optimisation. Influencers, peer producers and digital entrepreneurs engage in content creation, collaborative production and business activities by leveraging digital platforms. Redistribution involves peer-to-peer exchanges that promote resource efficiency. In co-testing and co-evaluation, consumers assess new products and provide feedback but do not create anything. Co-consumption focuses on shared use rather than individual creation. Participatory operations involve consumers in decision-making processes, fostering ownership and success without actual production. Mass customisation allows consumers to personalise products on a large scale, combining consumer input with industrial production processes. Co-production and co-determination directly involve consumers in production processes and decision-making, fostering a sense of ownership and relevance.

High level of effortNine terms – co-design, co-creation, co-distribution, co-communication, co-promotion, crowdsourcing, self-production, and experience co-creation – describe activities in which consumers are directly involved in creating or producing products and services. They closely align with the prosumer concept, emphasising individual creation and value generation. Co-design and co-creation focus on collaborative development with significant consumer input. Co-distribution and co-communication involve consumers in distribution and promotional activities, leveraging their networks and resources. Co-promotion uses consumer advocacy to enhance brand reputation. Crowdsourcing taps into collective intelligence for problem-solving and innovation. Self-production and prosumption embody the core prosumer activities of producing goods for personal use. Experience co-creation transforms consumers into active participants, enhancing satisfaction and engagement.

By examining these relationship levels, we can see that, while there is an overlap between these terms and prosumer activities, each has distinct consumer effort characteristics and levels. Understanding these distinctions helps clarify the unique role of prosumers in the economy. Prosumers are not merely participants in a collaborative process; they are active creators who generate significant value through their direct engagement in production. Yet, as shown previously, effort is differentiated according to the production criterion and, to a lesser extent, depending on the tangibility of the outputs. This differentiation is crucial for accurately characterizing and leveraging prosumers’ contributions in various economic contexts.

The roles of prosumers in the sharing economy ecosystemCooperation in the sharing economyIn the sharing economy ecosystem, the collaboration between prosumers, businesses and individuals reflects different modes of participation, and there are significant differences in the levels of involvement between consumers and companies (Tapscott & Williams, 2008). Prosumers often engage in peer-to-peer exchanges, contribute to collaborative platforms and participate in hybrid models that integrate consumer and business interactions. Their active involvement drives the dynamics of the sharing economy, fostering innovation, enhancing personalisation and promoting sustainable practices (Botsman & Rogers, 2010).

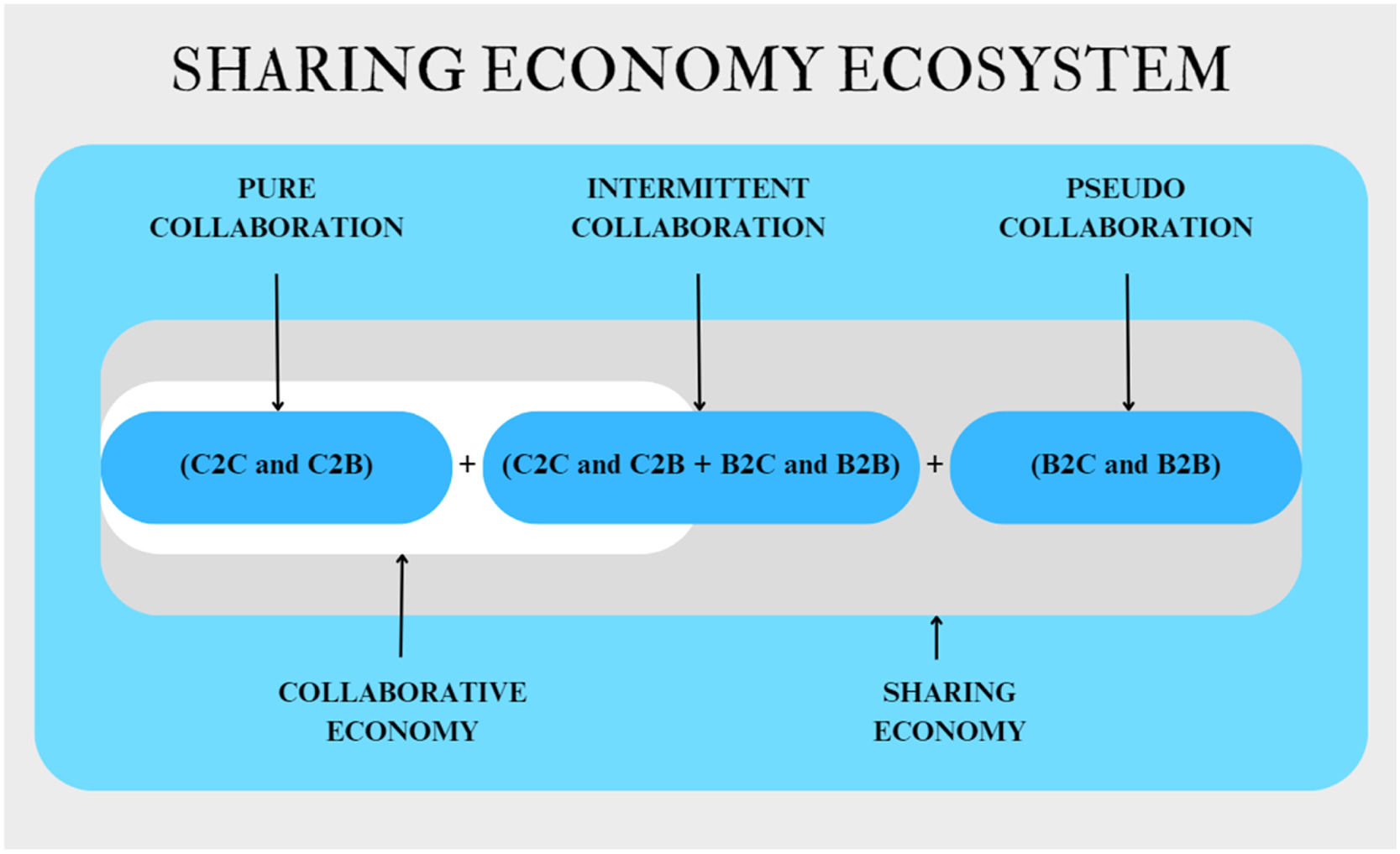

Fig. 4 shows that the sharing economy ecosystem includes three forms of collaboration: pure collaboration, intermittent collaboration and pseudo collaboration (Ertz, 2020). This framework highlights how the involvement of consumers and businesses varies. Pure collaboration involves direct exchanges between consumers (C2C) or between consumers and businesses (C2B). In these interactions, consumers often act as providers, contributing goods or services in a peer-to-peer manner. Examples include flea markets and service provision in the gig economy (Lamberton & Rose, 2012).

Intermittent collaboration includes a mix of C2C, C2B, business to consumers (B2C) and business to business (B2B) interactions. Platforms such as Airbnb exemplify this model by facilitating peer-to-peer rentals and allowing businesses to offer services. This hybrid model captures the essence of many contemporary sharing economy platforms (Lamberton & Rose, 2012). Pseudo collaboration refers to traditional business models in which businesses (B2C and B2B) are the primary providers. Zipcar, which operates on a B2C model, falls under this category (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012). By understanding these distinctions, the role of prosumers within the sharing economy ecosystem can be better appreciated.

Collaborative consumption reshapes traditional market behaviours by incorporating bartering, gifting, swapping, reselling, lending and renting on a larger scale (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). This socioeconomic model leverages underutilised resources by improving the match between supply and demand and bypassing conventional intermediaries (Botsman & Rogers, 2010). Despite this, Belk (2014, p. 7) noted that genuine sharing and ‘pseudo-sharing’ can occur on the same platform. Conventional consumption models (B2C or B2B) in a marketer-managed system are often labelled as part of the sharing economy (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Lamberton & Rose, 2012).

In summary, the sharing economy is a complex ecosystem in which different collaboration models coexist. Prosumers are central to this ecosystem, merging consumption and production roles. Their active engagement enriches the sharing economy and promotes sustainability and innovation across various sectors (Ertz et al., 2020; Pienkowski, 2021).

Challenges and corresponding solutions for prosumers in the sharing economyAlthough the emerging sharing economy provides a valuable platform for collaboration between prosumers and businesses, prosumers still face challenges across the three forms of collaboration, hindering the smooth operation of the collaborative consumption model. One major issue is the heterogeneity of consumers, which refers to the high diversity of individuals acting as producers and consumers. The variability in the service-related skills of prosumers often leads to inconsistencies in service quality, posing potential risks to consumer trust and satisfaction. Prosumers in the sharing economy are not necessarily professional service providers; in fact, the low entry barriers to becoming a prosumer mean that individuals with insufficient service-related skills can easily join sharing platforms. The lack of professionalism can result in poor consumer experiences, as some prosumers may fail to meet the expected service standards, severely damaging the reputation of the platform or industry.

Platforms often fail to provide systematic training and support for prosumers, exacerbating the problem of inconsistent service quality. Without proper training or guidance, prosumers usually lack the necessary expertise to deliver satisfactory services or effectively with customers. Moreover, prosumers’ qualifications and skills can significantly influence consumer perceptions and evaluations of the service they receive. This variability makes it challenging to consistently meet consumer expectations.

In addition, prosumers may struggle with role management (Xiang, 2022). The dual identity of being a consumer and a service provider often causes discomfort for individuals unaccustomed to the responsibilities typically associated with service provision. This discomfort can negatively impact the overall experiences of prosumers and consumers, especially when their roles are not clearly defined or managed. Quality control is another persistent challenge, as reliance on a crowdsourced supply makes it difficult to maintain service consistency. When consumer expectations are unmet, dissatisfaction can arise, potentially affecting the overall viability of the platform. Furthermore, platforms often face difficulties in retaining service providers who may engage opportunistically, thereby compromising the reliability and long-term sustainability of the service.

To address these challenges, collaborative businesses have implemented strategies to interact effectively with prosumers and improve their participation and service quality in the sharing economy. One key strategy is the establishment of training programmes. By providing systematic training and support, such as workshops or online courses, companies can help prosumers acquire the skills they need to deliver services effectively. This not only enhances service quality but also boosts prosumers’ confidence in their roles.

Some companies and platforms have created interactive online and offline communities so that prosumers can share knowledge, experiences and resources. These communities foster a sense of belonging among prosumers, strengthen their commitment to the sharing economy platform and encourage long-term engagement. Additionally, monitoring and evaluation systems help companies assess the service quality of prosumers. Through regular feedback, performance evaluations and rewards, businesses can encourage prosumers to maintain high service standards, ensuring consistent service delivery. By tailoring support and engagement strategies to the unique attributes of each prosumer, companies can improve service provision and overall performance, thereby enhancing prosumers’ identity (i.e., as in sense of self) and engagement with the platform.

These challenges and solutions highlight the complexity of the prosumer roles in the sharing economy and the need for platforms to implement better support structures, training programmes and quality control measures to enhance service delivery, consumer trust and the overall effectiveness of the sharing economy model.

Theoretical critiques and perspectivesA nuanced examination of the prosumer phenomenon reveals a complex landscape in which empowerment and exploitation coexist, necessitating a balanced and informed perspective (Comor, 2011; Zwick et al., 2008). One of the primary advantages of prosumerism is that it empowers individuals. By enabling consumers to participate directly in the production and modification of products and services, prosumerism democratises the creation process, fosters innovation and enhances consumer satisfaction through personalised and customised offerings (Botelho et al., 2021; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). Lang et al. (2021) showed how digital platforms have enabled unprecedented user participation and creativity. Such empowerment allows prosumers to control production processes, leading to a sense of agency and community engagement (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

However, the optimistic view of prosumer empowerment is tempered by critiques highlighting potential exploitation. Pienkowski (2021) argued that prosumers often contribute to value creation without adequate compensation, raising questions about the fairness of this economic model. Lambert (2015, p. 10) introduced the term ‘shadow work’ to describe the unpaid labour that benefits corporations. This critique is particularly salient in the context of the sharing economy, where platforms such as Airbnb and Uber have been accused of leveraging prosumer labour without providing fair remuneration or adequate labour protection (Slee, 2015). These perspectives highlight the need for policies that ensure fair compensation and ethical practices (Pienkowski, 2021).

The commercialisation of prosumption adds another layer of complexity. Pienkowski (2021) highlighted the dual nature of prosumption as both empowering and potentially exploitative. Integrating prosumer activities into corporate strategies can lead to the monetisation of UGC and the use of prosumer labour to drive profits (Comor, 2011; Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). This blurring of consumer and producer roles often leaves prosumers vulnerable to exploitation without proper recognition or reward (Comor, 2011). These critiques underscore the need for ethical practices and fair compensation frameworks to ensure that prosumers are not merely exploited for their contributions but are recognised and rewarded for their roles in the value creation process (Pienkowski, 2021).

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers and industry leaders must develop frameworks that balance the benefits of prosumer engagement with protections against exploitation. This includes establishing fair compensation models, ensuring transparency in corporate practices and promoting ethical standards that respect the contributions of prosumers (Pienkowski, 2021). Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010) suggested that a more equitable sharing of the economic value generated by prosumers could help address these concerns. Botelho et al. (2021) emphasised recognising and rewarding user innovation to sustain the prosumer model.

Despite the aforementioned critiques, the prosumer model remains a powerful driver of innovation and economic development. By directly engaging consumers directly, companies can tap into diverse perspectives and harness collective creativity (Tapscott & Williams, 2008). This collaborative approach can lead to more personalised products and services, enhancing customer satisfaction and fostering brand loyalty (Leal et al., 2024). Furthermore, the prosumer model promotes sustainability by encouraging the production of goods and services that meet actual consumer needs, thereby reducing waste and inefficiency (Botelho et al., 2021).

The broader economic implications of prosumption are significant. While some scholars have argued that the sharing economy exacerbates economic inequalities (e.g., Slee, 2015), others have suggested that it can lead to more equitable outcomes by decentralising production and providing opportunities for individual entrepreneurship (Tapscott & Williams, 2008). This debate highlights the need for continued research and policy development to address the inherent tensions within the prosumer model (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010).

In summary, the prosumer embodies potential as well as peril. It empowers individuals and fosters innovation but also risks exploitation and inequality. The challenge lies in navigating this complex landscape to develop sustainable and inclusive economic models.

Proposed prosumer frameworkBased on the conceptual analysis and the challenges and theoretical critiques that prosumers face in the current economic landscape, the comprehensive framework depicted in Table 5 was developed to assess prosumers’ self-reported engagement (i.e., involvement in prosumption activities) and perceived gains and savings across various prosumption activities. This framework can be used as a qualitative or quantitative assessment tool to gauge prosumer involvement in diverse areas by identifying co-creation and microentrepreneurship, allowing for a precise evaluation of prosumer engagement. The behaviour and participation indicators - refers to specific prosumer activities and their frequency, e.g. weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, semi-annual or annual. These elements are informed by prosumers. Perceived gains represent the monetary value that prosumers perceive they generate when engaging in activities in a particular sector, reflecting their economic contribution to that field. Perceived savings reflect the amount of money that prosumers perceive that they save due to their participation in prosumer activities. These savings serve as a form of indirect compensation. The framework also highlights the degree of exploitation that prosumers face across different sectors and domains and indirectly measures the social and economic sustainability of prosumerism.

Proposed prosumer framework.

| Sector | Behaviour and Participation Rate | Perceived Gains | Examples of Perceived Savings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Actively manage and share personal health data | Monetary value gained from activities as a prosumer in healthcare | Reduced medical expenses, preventive care or self-monitoring |

| Create and share health-related knowledge with others | |||

| Create health-related courses and/or educational materials | |||

| Use health-tracking apps and share personal data with others | |||

| Participate in online health communities | |||

| Promote personalised and participatory healthcare through personal actions | |||

| Receive offline medical services and provide evaluations of them to the medical staff | |||