Entrepreneurship education (EE) is a pivotal inspiration for students’ efforts to acquire entrepreneurial knowledge (EK), which can enable them to found new business ventures. We draw on entrepreneurial inspiration theory to develop a framework that we use to test (a) the mediating effect of entrepreneurship education and (b) the moderating effects of different pedagogical approaches on the relationship between students’ entrepreneurial intention (EI) and EK. The results reveal that entrepreneurship has significant and positive direct and indirect effects on the relationship between EI and EK. Importantly, our analyses reveal that the different pedagogical approaches used in business schools to impart EK have strong positive moderating effects in this context. An examination of these pedagogical approaches indicates that assessments can enhance university students’ EK most significantly, followed by in-class activities and lectures. We discuss the results of this study and its implications for entrepreneurship educators and policymakers seeking to design effective curricula.

The question of how entrepreneurship can be promoted is important in the business education literature, and the acquisition of entrepreneurial knowledge (EK) represents a promising way of enhancing students' entrepreneurial characteristics (Lin et al., 2024; Politis, 2005; Scuotto & Morellato, 2013). Entrepreneurship has been widely reported to be teachable (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Drucker, 2014; Neck & Greene, 2011; Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021). Consequently, interest in the ways in which entrepreneurship is taught in a classroom has increased as business schools continue to improve their pedagogical approaches in the context of entrepreneurship education (EE) (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Haddad et al., 2021). Over the past three decades, EE has developed enhanced pedagogical approaches with the goal of inspiring entrepreneurship students to obtain positive learning outcomes (Haddoud et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023). Researchers who have investigated EE have also explored the different pedagogical approaches that can be employed to enhance EK (Hahn et al., 2017; Politis, 2005). In the context of EE, various teaching methods and different types of content are employed to enhance students’ entrepreneurial capability and inspire them to engage in entrepreneurial learning (Fayolle et al., 2006; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022).

Inspiration, as an emotional factor, is a critical driver of EE (Souitaris et al., 2007). Researchers investigating this topic have increasingly used inspiration as a theoretical perspective in their efforts to understand how EE can inspire students to engage in entrepreneurship learning (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022). Entrepreneurial inspiration refers to “a change of hearts (emotion) and minds (motivation) that is triggered by events or inputs in the context of educational programs, thereby encouraging individuals to consider entrepreneurship as a potential path” (Wang et al., 2022; See also Souitaris et al., 2007, p. 573). EE is a significant source of inspirational stimuli that is positively related to students’ entrepreneurial intentions (EI) (Li et al., 2023). Such inspiration can expand students’ entrepreneurial awareness, thereby presenting them with several opportunities to engage in entrepreneurship (Ndou et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2022) identified two critical dimensions of entrepreneurial inspiration: theoretical inspiration and practical inspiration. While theoretical inspiration is the result of external factors such as tutors, peers, events, literature, or case studies, practical inspiration is the result of students’ hands-on experiences, for example, with business simulations and exercises (Nabi et al., 2018). In particular, students’ participation in class activities that can offer them practical insights is associated with such practical inspiration (Wang et al., 2022). Many studies in this field have identified EI as a critical antecedent of entrepreneurial behavior (Souitaris et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022). Students’ EI represents their desire to learn about and engage in entrepreneurial behavior (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022). Previous studies have examined the nuanced relationships between EI and EE, although they have yielded varied results. While some studies have reported a positive association between EI and EE, other studies have reported mixed or even negative relationships in this context (Mentoor & Friedrich, 2007; Oosterbeek et al., 2010; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015).

Despite improvements in our understanding of the interaction between EI and EK, the factors that influence students' ability to acquire EK via different pedagogical approaches require further analysis (Adeel et al., 2023; Blankesteijn et al., 2024). We address this critical research gap by answering two important research questions: What role does EE play in the relationship between students’ EI and EK? How do different pedagogical approaches contribute to this relationship? We draw on entrepreneurial inspiration theory (Li et al., 2023; Souitaris et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022) to develop a conceptual framework that we then use to investigate the mediating effect of EE in the relationship between EI and EK. Moreover, we empirically examine the moderating roles played by three different pedagogical approaches that are typically used in business schools, i.e., lectures (which are delivered by tutors or guest speakers), in-class activities (i.e., tasks that engage students during the learning process), and assessment methods (i.e., assignments that aim to measure learning outcomes)(Biggs & Yang, 2011; Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Nabi et al., 2017).

Our study, which focused on a cohort of 201 undergraduate and postgraduate students at an Australian university, contributes to the discourse concerning the teachability of entrepreneurship by exploring impactful pedagogical approaches that can be employed in this context (Allal-Chérif & Bidan, 2017; Nabi et al., 2017). First, we highlight the nonuniform effects of different pedagogical approaches on EK. Second, we emphasize the critical role played by assessments in students’ learning, as learning leads to the acquisition of knowledge (Black & Wiliam, 1998, 2018). Our findings suggest that assessments have the most substantial positive moderating effect in this context, followed by in-class activities and lectures; these results thus highlight the importance of innovative pedagogical design with respect to efforts to enhance students’ learning outcomes. These insights have significant implications for entrepreneurship scholars and educators seeking to design EE programs that can effectively enable students to acquire EK and indicate that business schools should use innovative pedagogical approaches, particularly those that involve experiential, authentic in-class activities and assessments.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis developmentEntrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial knowledgeNumerous studies on EE have reported empirical evidence indicating that higher levels of EI among EE students increase their likelihood of founding entrepreneurial ventures (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022; Kautonen et al., 2015; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015). Other studies have emphasized the fact that EI is not the sole outcome of EE; namely, other equally important outcomes include the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and behavioral changes that can impact students and the broader entrepreneurship ecosystem by offering economic benefits and creating jobs (Aljohani et al., 2022; European Commission, 2015; Huang et al., 2023). When students enroll in EE programs, they likely already desire to become entrepreneurs or explore career options that could allow them to take responsibility for their own destinies (Adeel et al., 2023). High-profile entrepreneurs, incubators, accelerators, and television series can trigger this stage of pre-EI via media coverage, exhilarating performances, and emotionally charged presentations.

Enrollment in EE can reflect students’ personal attitudes, which refer to their degree of attraction toward the possibility of becoming entrepreneurs and their belief that doing so is likely to lead to positive outcomes (Haddad et al., 2021). Positive personal attitudes toward entrepreneurship often reflect the desire for autonomy and control over one's career path (Adeel et al., 2023), thus suggesting that students who enroll in EE exhibit favorable personal attitudes toward entrepreneurship. Students who exhibit positive entrepreneurial attitudes are intrinsically motivated to learn and develop their skills, and they are more likely to engage in educational opportunities that are in line with their goals (Fayolle & Gailly, 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Thus, motivated students who exhibit such positive entrepreneurial attitudes are more likely to acquire EK, thus encouraging them to develop the proactive mindset that is crucial with respect to entrepreneurial success. Fretschner and Lampe's (2019) investigated more than 300 undergraduate entrepreneurship students at a German university, revealing that personal attitudes positively influence EI. According to Ajzen (2001), positive entrepreneurial attitudes indicate a favorable disposition toward EI. Previous researchers have reported that strong personal attitudes toward entrepreneurial education (EE) positively predict EI (Kautonen et al., 2015; Turner & Gianiodis, 2018). Overall, we propose that students’ enrollment in EE programs reflects their intrinsic motivation to acquire the knowledge, skills, and formal learning that are necessary to start business ventures and become entrepreneurs. On this basis, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: Students who exhibit EI are more likely to acquire EK.

EE provides a platform where students can engage socially with like-minded peers who also aspire to be entrepreneurs (Adeel et al., 2023; European Commission, 2015). Enrollment in an EE program indicates that students aspire to be entrepreneurs, i.e., to be their own bosses and to found entrepreneurial ventures. Aspirations involve desires, preferences, choices and calculations (Appadurai, 2004, p. 67). Such aspirations reflect a person's goals for the future and how far students can progress in their education (Schoon & Polek, 2011). In our study, we combine the notion of aspiration with that of inspiration to provide a theoretical framework for EE. Students who aspire to become high-profile entrepreneurs or to control their own destinies often seek inspiration within the entrepreneurial domain. The notion of inspiration, which refers to a motivating, elating feeling that is directed toward a specific goal (Thrash & Elliot, 2004), has been used as a theoretical concept in several disciplines, including entrepreneurship studies. Inspiration refers to strong, sometimes irrational emotions that excite people and encourage them to act. In the context of entrepreneurship studies, entrepreneurial inspiration refers to a change in emotions and motivation that is triggered by events or program inputs, which can thus lead students to consider entrepreneurship as a career choice (Cui et al., 2021; Souitaris et al., 2007). The notion of entrepreneurial inspiration indicates that among students who are inspired by the prospect of becoming entrepreneurs, exhibiting preexisting EI and enrolling in an entrepreneurship course signal their commitment to the task of acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary to embark on their entrepreneurial learning journeys (Lyu et al., 2023b; Souitaris et al., 2007).

Entrepreneurial learning is a process that involves the acquisition of knowledge that can prepare students more effectively to found their own business ventures (Hahn et al., 2017; Politis, 2005). This process combines theoretical understanding (i.e., know-what and know-how) with practical application (i.e., know-who and know-when) (Kolb, 1984, p. 41), such as by learning to interact with others through roleplaying or participation in pitch presentations, internships or field research in the context of entrepreneurship (Cope et al., 2007; Johannisson, 1991). Students who intend to become entrepreneurs and who actively pursue entrepreneurship education with the aim of acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary to achieve their goals (Appadurai, 2004; Currid-Halkett, 2017; Hart, 2016; Khattab, 2015) are more likely to be inspired to acquire EK as they progress through their entrepreneurship education (Aljohani et al., 2022). This relationship between entrepreneurship education and EK (Fayolle et al., 2006; Johannisson, 1991; Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005) leads us to propose our second hypothesis:

H2: Entrepreneurship education positively mediates the relationship between EI and EK.

Souitaris et al. (2007) reported that entrepreneurial inspiration predicts EI more strongly than other variables, such as EE. Students engaged in EE may find themselves either inspired or not inspired by the curricula or the teacher's delivery, thus suggesting that inspiration represents an emotional drive that can change the dynamics underlying learning outcomes among students (Cui et al., 2021; Souitaris et al., 2007). Other studies have identified two distinct aspects of inspiration: theoretical inspiration and practical inspiration (Wang et al., 2022). In the context of entrepreneurship education, theoretical inspiration includes engaging in the process of learning about entrepreneurship, such as by attending lectures, developing an interest in research, exploring case studies, and participating in external events, such as seminars and conferences, to expand one's EK (O'Connor, 2022; Thornton et al., 2011). Practical inspiration is the result of active participation and interaction with one's educators and peers in the context of activity-driven learning exercises, which may involve roleplaying or business simulations as well as participation in student associations and incubator/accelerator programs (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Kwong et al., 2022; Nabi et al., 2018; Padilla-Meléndez & del-Aguila-Obra, 2022). Previous studies on the impact of pedagogy have suggested that this factor plays an important role in this context (Haddoud et al., 2022). Other studies have assessed the effectiveness of different teaching methods and reported that undergraduate and Master of Business Administration (MBA) students identified simulations, case studies, and lectures as the most effective ways of developing their interpersonal skills, self-awareness, and problem-solving abilities (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018). Another study that investigated postgraduate entrepreneurship, management, and economic students in Tehran identified positive relationships among EE, entrepreneurship curricula, and pedagogical methods and explored the impacts of these factors on entrepreneurial behavior. However, the descriptions of entrepreneurship curricula and pedagogical methods provided in that study were broad, and the ways in which these factors were operationalized was unclear (Sherkat & Chenari, 2022).

From a pedagogical perspective, what are the specific factors that can inspire entrepreneurship students? We draw on inspiration theory (Nabi et al., 2018; Souitaris et al., 2007; Thrash et al., 2014) and recognize the critical roles played by pedagogical content and delivery in the process of inspiring EE students to engage in learning and knowledge acquisition, thus leading us to propose that EE is positively correlated with EK:

H3: The pedagogy associated with entrepreneurship education positively moderates the relationship between EI and EK.

As mentioned, the pedagogy used in EE encompasses the educational process by which students can be equipped with entrepreneurial attitudes and the corresponding skills. Pedagogical frameworks guide this process of learning and knowledge acquisition by integrating teaching strategies (in terms of curricula and design), learning activities (i.e., tasks that engage students in the learning process), and assessment methods (i.e., assignments that aim to measure learning outcomes) (Aljohani et al., 2022; Biggs & Yang, 2011; Knight et al., 2014; Nabi et al., 2017). These pedagogical frameworks include developing specific learning objectives, pedagogical content, teaching approaches, and assessments to facilitate students’ learning (Fayolle et al., 2006; Knight et al., 2014). Some scholars have claimed that a comprehensive framework can enhance our ability to evaluate the pedagogy used in EE, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the development of corresponding teaching methods and the promotion of entrepreneurial outcomes (Nabi et al., 2017). In their systematic review of the literature on EE, these authors presented a framework that can be used to evaluate EE outcomes in a more robust manner. This framework includes four teaching and learning models: the supply model, the demand model, the competence model, and the hybrid model. According to the supply model, instructors deliver knowledge to students via lectures, readings, and other didactic methods; accordingly, this model features only limited interaction between instructors and learners. In this teaching approach, the model employed is passive or "instructivist" (Grimley et al., 2011; O'Connor, 2022). Grimley et al. (2011) suggested that while lectures can disseminate knowledge, they may fail to instill essential social and behavioral skills in students.

In contrast, contemporary education tends to feature a preference for a "constructivist" pedagogy, in which context students actively participate in class and collaborate with their peers to achieve shared goals, such as in the contexts of student-led discussions and team projects (Adeel et al., 2023; Johannisson, 1991; Johannisson et al., 1998; Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005). Nabi et al.’s (2017) demand model exemplifies a constructivist approach to the processes of learning and teaching that emphasizes interaction and engagement. The competence model is closely in line with the constructivist approach, and it involves experiential learning through various activities, such as creative problem solving, simulations, case studies, presentations, and even the development of new business ventures (Adeel et al., 2023; Johannisson, 1991; Johannisson et al., 1998; Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2005). The final model included in Nabi et al.’s (2017) framework is a hybrid model that combines elements from the supply, demand, and competence models. In each of these models, the delivery of knowledge to students plays a pivotal role. Nevertheless, the extent to which students can be inspired by the teaching content and delivery methods has a strong influence on their learning outcomes, which, in turn, shape their ability to acquire EK. Students are more likely to learn when they are inspired (Souitaris et al., 2007; Thrash & Elliot, 2004; Wang et al., 2022), exhibit strong personal attitudes toward their own learning (Ajzen, 1991, 2001; Fretschner & Lampe, 2019) and are motivated to achieve their goals (Appadurai, 2004). Accordingly, what aspects of the pedagogy used in EE can provide the inspiration necessary to enhance EK outcomes? The pedagogical methods employed in EE and business studies typically include lectures and in-class activities (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018; Sherkat & Chenari, 2022). An essential aspect of these methods is their reliance on assessments, which can be used to measure students’ learning and demonstrate their progress (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Knight et al., 2014). However, some educators have warned that assessments can inadvertently encourage students to learn only in accordance with the requirements of such assessments, thereby potentially preventing them from engaging in the deeper processes of knowledge synthesis, construction, and practical application (Elton & Johnston, 2002). To address this issue, educators have highlighted the importance of the validity of such assessments to ensure that these assessments are designed to align with the stated learning objectives of the course and that they can be adapted to improve learning outcomes (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Elton & Johnston, 2002; Knight et al., 2014).

We build on previous research that has reported that entrepreneurship can be taught and that EE supports entrepreneurial learning and knowledge acquisition by examining the ways in which various pedagogical approaches, including lectures, in-class activities, and assessments, contribute to learning and perceived knowledge gains. On this basis, we propose Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c:

H3a: Perceptions of inspiring lectures are positively linked to EK outcomes.

H3b: Perceptions of inspiring in-class activities are positively linked to EK outcomes.

H3c: Perceptions of inspiring assessments are positively linked to EK outcomes.

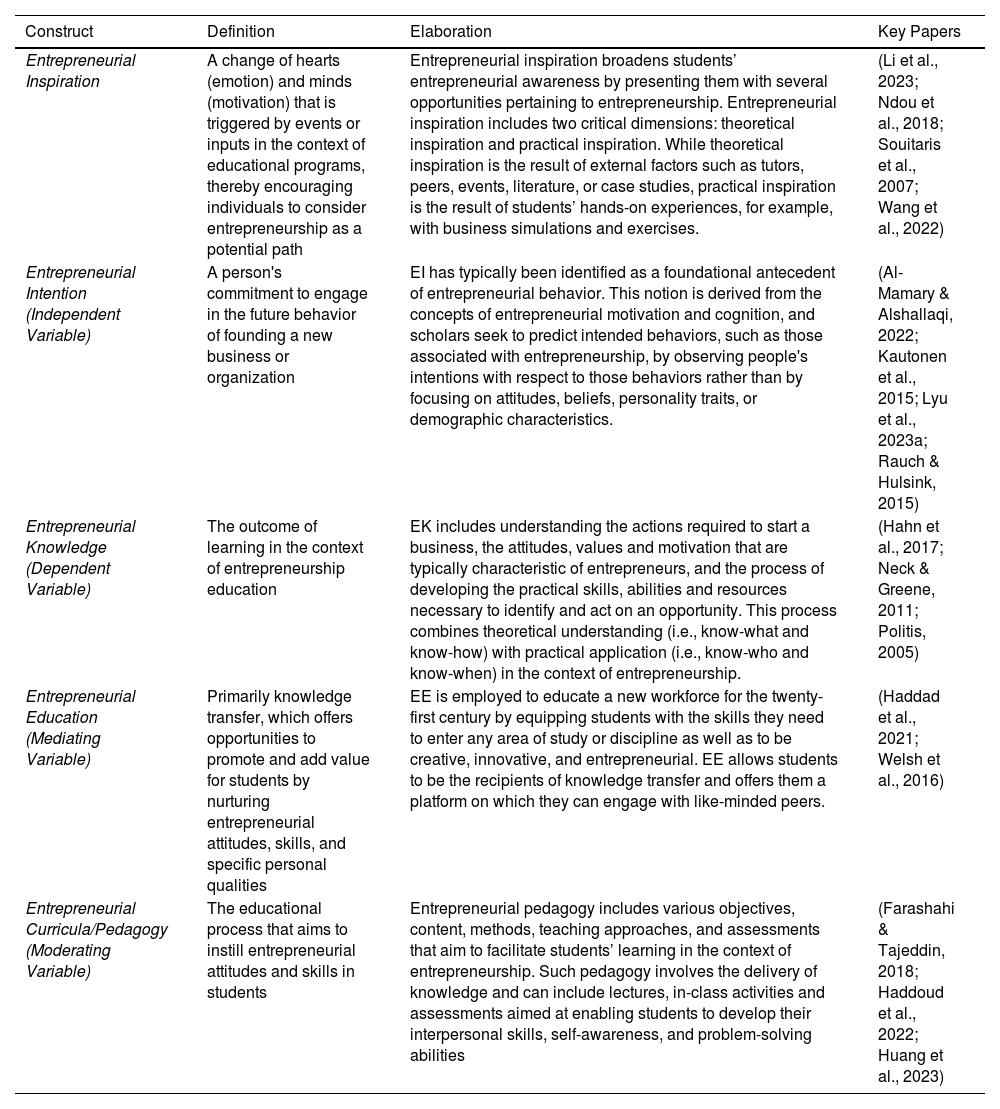

Fig. 1 presents the hypothesized relationships, while Table 1 summarizes the constructs alongside their definitions and relevant critical papers.

Construct definitions and elaboration – Summary of the literature review.

| Construct | Definition | Elaboration | Key Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Inspiration | A change of hearts (emotion) and minds (motivation) that is triggered by events or inputs in the context of educational programs, thereby encouraging individuals to consider entrepreneurship as a potential path | Entrepreneurial inspiration broadens students’ entrepreneurial awareness by presenting them with several opportunities pertaining to entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial inspiration includes two critical dimensions: theoretical inspiration and practical inspiration. While theoretical inspiration is the result of external factors such as tutors, peers, events, literature, or case studies, practical inspiration is the result of students’ hands-on experiences, for example, with business simulations and exercises. | (Li et al., 2023; Ndou et al., 2018; Souitaris et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022) |

| Entrepreneurial Intention (Independent Variable) | A person's commitment to engage in the future behavior of founding a new business or organization | EI has typically been identified as a foundational antecedent of entrepreneurial behavior. This notion is derived from the concepts of entrepreneurial motivation and cognition, and scholars seek to predict intended behaviors, such as those associated with entrepreneurship, by observing people's intentions with respect to those behaviors rather than by focusing on attitudes, beliefs, personality traits, or demographic characteristics. | (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022; Kautonen et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2023a; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015) |

| Entrepreneurial Knowledge (Dependent Variable) | The outcome of learning in the context of entrepreneurship education | EK includes understanding the actions required to start a business, the attitudes, values and motivation that are typically characteristic of entrepreneurs, and the process of developing the practical skills, abilities and resources necessary to identify and act on an opportunity. This process combines theoretical understanding (i.e., know-what and know-how) with practical application (i.e., know-who and know-when) in the context of entrepreneurship. | (Hahn et al., 2017; Neck & Greene, 2011; Politis, 2005) |

| Entrepreneurial Education (Mediating Variable) | Primarily knowledge transfer, which offers opportunities to promote and add value for students by nurturing entrepreneurial attitudes, skills, and specific personal qualities | EE is employed to educate a new workforce for the twenty-first century by equipping students with the skills they need to enter any area of study or discipline as well as to be creative, innovative, and entrepreneurial. EE allows students to be the recipients of knowledge transfer and offers them a platform on which they can engage with like-minded peers. | (Haddad et al., 2021; Welsh et al., 2016) |

| Entrepreneurial Curricula/Pedagogy (Moderating Variable) | The educational process that aims to instill entrepreneurial attitudes and skills in students | Entrepreneurial pedagogy includes various objectives, content, methods, teaching approaches, and assessments that aim to facilitate students’ learning in the context of entrepreneurship. Such pedagogy involves the delivery of knowledge and can include lectures, in-class activities and assessments aimed at enabling students to develop their interpersonal skills, self-awareness, and problem-solving abilities | (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018; Haddoud et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023) |

To test our research hypotheses, we collected survey data from students at an Australian university. We recruited students from both undergraduate and postgraduate programs in entrepreneurship or leadership as well as dual majors who studied both subjects. A total of 2,195 students (59 % in entrepreneurship and 41 % in leadership) were invited to participate in this research via email as well as via an online survey link that was accessible on the university's online platform. A brief cover letter explained the purpose of this study, ensured the participants of the anonymity of their responses, and highlighted the voluntary nature of participation in this research, which received approval from the university's ethics committee. We received 307 responses (for a response rate of 14 %) during the data collection process, and after careful data cleaning, 201 valid and complete responses were included in our analysis. This sample size fulfilled the criteria for both parametric and nonparametric tests (Hair et al., 2010; Sekaran, 2000). Among these respondents, 44.3 % were male, while 55.7 % were female; furthermore, the majority of respondents (60.2 %) were pursuing postgraduate degrees, and the average age of the participants was 24.06 years (SD = 5.18). Demographics information concerning the participants in this study is presented in Table 2.

Demographic information concerning the participants in this study.

| Students | Frequency | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24.06 | 5.18 | |

| Gender | Male=89, Female =112 | 1.44 | .498 |

| Undergraduate - Entrepreneurship | 75 | 1.63 | .485 |

| Undergraduate - Leadership | 31 | 1.85 | .362 |

| Postgraduate - Entrepreneurship | 66 | 1.67 | .471 |

| Postgraduate - Leadership | 50 | 1.75 | .433 |

| Enrollment | Domestic=92, International=109 | 1.54 | .499 |

Note: Some students (n = 21) who were studying for double majors selected both entrepreneurship and leadership.

We used validated scales developed by previous researchers and sought input from various experts, including academics and practitioners, to evaluate the content and face validity of our methodology and to enhance the design of the questionnaire in our specific context. Before we distributed the primary survey, we conducted a pilot study by reference to 20 university students to ensure that the items were clear; on the basis of the results of this pilot study, we made minor adjustments to the items. All multi-item measures were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = 'totally disagree' to 5 = 'totally agree'). We measured students’ EI (i.e., the independent variable) via seven items developed by Liñán and Chen (2009); an example item is “My goal is to become an entrepreneur”. We measured students’ EK via six items associated with Liñán and Chen's (2009) construct of perceived behavioral control (PCB), which was used as a proxy for PCB; an example item is “I know how to develop an entrepreneurial project”. To measure EE (mediating variable), we used three items drawn from Souitaris et al. (2007); an example item is “This unit inspired me with regard to entrepreneurship in general”. We also measured the following three dimensions of pedagogy (i.e., the moderating variables) via 18 items. (1) Lectures—we used four items, such as “The lecture materials apply to my unit of study”, to measure the extent to which students were inspired by lectures. (2) In-class activities—we used five items to measure the extent to which students were inspired by in-class activities, including “case study analysis” and “working in groups”. (3) Assessments— we investigated whether nine types of assessments, such as “individual written reports”, “group written reports” and “pitch presentations”, could evaluate students. We also included the following open-ended question at the end of the survey: “Please explain briefly the aspects of the unit (unit contents, teaching method, and assessments) that inspire you to start your own new business venture”. The aim of this investigation was to examine how and why specific pedagogical approaches inspired students.

We also included several control variables to account for the potential influence of other factors that could affect the hypothesized relationships. The control variables included students’ age (logarithm of years), gender (three dummy indicators, i.e., 1=male, 2=female, 3=nonbinary/third gender) and level of education (two dummy indicators, i.e., 1= undergraduate, 2=postgraduate or higher).

Goodness of the dataWe observed no significant differences between late and early responses at the 5 % level of significance, thus indicating that nonresponse bias is not a primary concern in this research (O'Cass & Ngo, 2012). The fact that moderate-to-high interfactor variable correlations were observed in this context (as indicated in Table 3) prompted us to perform a collinearity diagnostic test. However, all variables had variance inflation factor (VIF) values <3, i.e., below the threshold of 10, thus addressing potential concerns pertaining to multicollinearity (Kumar & Zaheer, 2019; Liu et al., 2016). Data normality and homoscedasticity were also established through a visual examination of the scatter plots, histograms, residuals, and normal probabilities (Hair et al., 2010). To address potential common method bias, we employed Harman's single-factor test, which involved including all items in an unrotated factor analysis (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The single factor thus extracted accounted for 35.7 % of the total variance (below 50 %), thus indicating that common method bias was not a major issue in this research. Furthermore, the inclusion of interaction effects in the regression models minimized this risk (Siemsen et al., 2010).

Pearson correlation coefficients.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age | 24.05 | 5.18 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Entrepreneurship UG | 1.63 | .48 | .392&#¿;&#¿; | |||||||||||

| 3. Leadership UG | 1.85 | .36 | .232&#¿;&#¿; | -0.272&#¿;&#¿; | ||||||||||

| 4. Entrepreneurship PG | 1.67 | .47 | -0.342&#¿;&#¿; | -0.539&#¿;&#¿; | -0.269&#¿;&#¿; | |||||||||

| 5. Leadership PG | 1.75 | .43 | -0.361&#¿;&#¿; | -0.444&#¿;&#¿; | -0.214&#¿;&#¿; | .039 | ||||||||

| 6. Student type | 1.54 | .49 | .348&#¿;&#¿; | .613&#¿;&#¿; | .271&#¿;&#¿; | -0.557&#¿;&#¿; | -0.459&#¿;&#¿; | |||||||

| 7. Entrepreneurship intention | 3.40 | .52 | .069 | .038 | .142* | -0.283&#¿;&#¿; | .026 | .199&#¿;&#¿; | (0.76) | |||||

| 8. Education | 3.84 | .95 | -0.142* | .050 | .036 | -0.081 | -0.086 | .003 | .187&#¿;&#¿; | (0.70) | . | |||

| 9. Lectures | 4.61 | 1.10 | .142* | .213&#¿;&#¿; | .069 | -0.219&#¿;&#¿; | -0.080 | .161* | .242&#¿;&#¿; | .538&#¿;&#¿; | (0.68) | |||

| 10. In-class activities | 4.80 | 1.31 | .101 | .197&#¿;&#¿; | .119 | -0.281&#¿;&#¿; | -0.098 | .198&#¿;&#¿; | .241&#¿;&#¿; | .525&#¿;&#¿; | .604&#¿;&#¿; | (0.80) | ||

| 11. Assessments | 4.96 | 1.23 | .169* | .280&#¿;&#¿; | .084 | -0.258&#¿;&#¿; | -0.154* | .242&#¿;&#¿; | .203&#¿;&#¿; | .488&#¿;&#¿; | .598&#¿;&#¿; | .830&#¿;&#¿; | (0.89) | |

| 12. Entrepreneurial knowledge | 3.27 | .89 | .203&#¿;&#¿; | .004 | .271&#¿;&#¿; | -0.191&#¿;&#¿; | -0.065 | .100 | .355&#¿;&#¿; | .446&#¿;&#¿; | .433&#¿;&#¿; | .453&#¿;&#¿; | .485&#¿;&#¿; | (0.91) |

Note: Composite reliability values are provided in parenthesis on the diagonal.

UG = undergraduate; PG = postgraduate; Student type = domestic or international

We used multiple hierarchical regression and bootstrapping techniques with the assistance of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to conduct our analyses. These statistical techniques have increasingly been used by scholars seeking to investigate innovation and knowledge to test both direct and indirect effects and to examine the corresponding mediating and moderating relationships (Alam et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024; Malibari & Bajaba, 2022). Hierarchical regression analysis is not only more useful for independent examinations of the unique predictive power of each pedagogical approach to EK that are the other predictors included in our model; it also helps us control for the confounding effects of demographic variables (Alam et al., 2022; Kumar & Zaheer, 2019). Similarly, to examine the relevant mediating and moderating effects, we conducted tests on the basis of 5000 bootstrap samples, as recommended by Hayes (2013), with the assistance of the PROCESS macro (v. 4.3). This robust method can be used to generate asymmetric confidence intervals that can, in turn, be used to examine mediating effects. We relied on these analytical techniques to test six models at the 0.05 level of significance (as indicated in Table 4). Model 1 focuses on the control variables, Model 2 is used to assess the direct impact of EI on EK, and Model 3 is used to examine the overall direct effect of pedagogy on EK.

Regression.

| Entrepreneurial Learning (Dependent variable) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||||

| Control variables | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) |

| Age | .024 | .014 | .024 | .013 | .025* | .012 | .023 | .012 | .026 | .012 | .024 | .012 |

| Gender | -0.076 | .124 | -0.063 | .117 | -0.019 | .103 | -0.044 | .108 | -0.039 | .105 | -0.017 | .103 |

| Entrepreneurship UG | -0.093 | .296 | .106 | .283 | -0.185 | .251 | -0.153 | .266 | -0.159 | .258 | -0.231 | .254 |

| Leadership UG | .484 | .296 | .568* | .280 | .358 | .247 | .388* | .261 | .361 | .254 | .342 | .249 |

| Entrepreneurship PG | -0.291 | .225 | -0.049 | .218 | -0.004 | .191 | -0.073 | .202 | .006 | .197 | -0.046 | .195 |

| Leadership PG | -0.040 | .214 | .004 | .202 | .001 | .178 | -0.043 | .188 | -0.002 | .182 | -0.021 | .179 |

| Student type (domestic/international) | -0.121 | .196 | -0.223 | .186 | -0.154 | .164 | -0.135 | .173 | -0.123 | .168 | -0.145 | .165 |

| Main effects | ||||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention (H1) | .583&#¿;&#¿; | .119 | .422&#¿;&#¿; | .107 | .445&#¿;&#¿; | .113 | .418&#¿;&#¿; | .110 | .411&#¿;&#¿; | .108 | ||

| Pedagogy (combined) | .377&#¿;&#¿; | .049 | ||||||||||

| Lectures (Pedagogy) | .293&#¿;&#¿; | .051 | .173&#¿;&#¿; | .060 | .140&#¿;&#¿; | .060 | ||||||

| In-class activities (Pedagogy) | .182&#¿;&#¿; | .051 | .027 | .074 | ||||||||

| Assessment-types (Pedagogy) | .223&#¿;&#¿; | .078 | ||||||||||

| Interaction effects | ||||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention × Pedagogy (combined) | .357&#¿;&#¿; | .049 | ||||||||||

| Interaction (H3) | .208* | -0.086 | ||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention × Lectures | .280&#¿;&#¿; | .052 | ||||||||||

| Interaction (H3a) | .132 | .090 | ||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention × In-class activity | .254&#¿;&#¿; | .042 | ||||||||||

| Interaction (H3b) | .187* | -0.076 | ||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial intention × Assess types | .300&#¿;&#¿; | .044 | ||||||||||

| Interaction (H3c) | .217&#¿;&#¿; | .078 | ||||||||||

| Main effect R2 | .107&#¿;&#¿; | .206&#¿;&#¿; | .410&#¿;&#¿; | .330&#¿;&#¿; | .358&#¿;&#¿; | .396&#¿;&#¿; | ||||||

| Interaction ΔR2 | - | .099&#¿;&#¿; | .018* | .007 | .020* | .024&#¿;&#¿; | ||||||

Note. β = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error of the regression parameter estimate

Furthermore, Model 4, Model 5, and Model 6 are used to examine the direct effect of each pedagogical approach, i.e., lectures, in-class activities, and assessments, respectively, on EK. As indicated in Table 4, we also examine the interaction effects of each pedagogical approach on the basis of the corresponding model. This stepwise analytical approach facilitates a more precise investigation of whether each pedagogical approach significantly enhances the R2 in EK after the previous predictor(s) at every stage are taken into account. Additionally, we followed the recommendation of Aiken et al. (1991) to conduct simple slope tests to plot the interaction effects.

Construct validityWe conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses to assess the fit of the measurement model and to establish convergent and discriminant validity (Bagozzi et al., 1991; El Akremi et al., 2018). We tested various models, including five-factor, four-factor, three-factor, two-factor, and single-factor alternatives, and compared them with our proposed six-factor model. Each model exhibited significant changes in terms of the chi-square values (Δχ2 at p < 0.001), and the comparative fit index (CFI) for each of these models decreased by ≥ 0.01, thus indicating a significant reduction in model fit. As indicated in Table 5, our hypothesized six-factor model exhibited more substantial item&#¿;factor associations than did any of the alternative models. The composite reliability of the measures (which ranged from 0.68 to 0.91) reached the acceptable level of ≥.60 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), thus indicating the reliability and internal consistency of the measures. The average variance extracted values ranged from 40 % to 70 %, and the standardized factor loadings of the items on the constructs were > 0.50 and exhibited significant t values (p < 0.05), thus indicating both convergent and discriminant validity. Overall, our baseline six-factor model outperformed the alternative models (χ2/d.f. = 2.4, RMSEA = .08, TLI = .82, CFI = .83, and SRMR = .07), thus reinforcing its discriminant validity (Bagozzi et al., 1991; El Akremi et al., 2018).

Results of the test of the measurement model.

| Models | χ2/d.f. | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six factors (L, C, A, O, I, E) | 2.4 | .086 | .83 | .82 | .072 |

| Five factors (L, C, A, O, I+E) | 2.87 | .097 | .79 | .77 | .078 |

| Five factors (C, A, O, E, I+L) | 2.87 | .097 | .70 | .77 | .073 |

| Four factors (C, A, O, I+L+E) | 3.24 | .106 | .74 | .73 | .080 |

| Four factors (I, A, O+C, L+I) | 3.53 | .112 | .71 | .69 | .114 |

| Three factors (I+C+L, A, O) | 4.68 | .136 | .52 | .55 | .127 |

| Three factors (I, A, O+C+L+E) | 4.03 | .123 | .65 | .63 | .993 |

| Three factors (I, A+C+L+E, O) | 3.32 | .108 | .74 | .72 | .082 |

| Two factors (I+C+L+O, A+E) | 5.57 | .151 | .48 | .44 | .138 |

| Two factors (I+E, A+C+L+O) | 4.55 | .133 | .59 | .57 | .141 |

| One factor (L+C+A+O+I+E) | 5.69 | .153 | .46 | .43 | .139 |

Note. I=Entrepreneurial intention; E=Entrepreneurship education; O=Learning outcomes; L=Lectures; C=In-class activities; A=Assessments; + indicates the combination of different factors.

As indicated in Table 4, we tested six models and employed the change in R2 as a benchmark to gauge their predictability.

Main effectsIn Model 1, the control variables collectively accounted for 10.7 % of the variance in students' EK. The addition of EI (i.e., the independent variable) in Model 2 resulted in a significant change in R2 (ΔR2 = 0.099, F = 23.98, p < 0.01), which could account for 9.9 % of the variance in students' EK. Model 1 and Model 2 highlighted the significant positive relationship between students' EI and EK (β=0.58, p < 0.01), thereby supporting H1. In Model 3, pedagogy enhanced the explained variance in EK by 18.6 % (β=0.38, ΔR2=0.186, F=58.26, p < 0.01). Since we operationalized pedagogy on the basis of a combination of three different approaches (i.e., lectures, in-class activities, and assessments), we ran Models 4, 5, and 6 to examine the unique contributions of these approaches. Lectures increased the explained variance by 11.6 % (β=0.29, ΔR2=0.116, F=32.72, p < 0.01), thus indicating that lectures are significantly and positively related to students’ EK. In Model 5, we included in-class activities and controlled for the impacts of lectures and EI. This model exhibited a significant change (β=0.18, ΔR2=0.044, F=13.10, p < 0.01), thus indicating that in-class activities are positively and significantly related to students’ EK beyond the positive effect of lectures. Specifically, in-class activities accounted for 4.4 % of the explained variance in students’ EK. Finally, in Model 6, we included assessments and controlled for the positive impacts of lectures and in-class activities. The results indicated a significant improvement of 2.6 % in the explained variance in students' EK (β=0.22, ΔR2=0.026, F=8.17, p < 0.05).

Moderating effectsH3 proposed that pedagogy strengthens the positive relationship between students’ EI and EK. The results (Model 3) revealed that the interaction between EI and pedagogy was positive and significant (β=0.356, ΔR2=0.018, F=5.84, p < 0.01). Given this strong interaction, we assessed the contributions of each pedagogical approach (i.e., lectures, in-class activities, and assessments). In Model 4, lectures did not significantly moderate the relationship between students' EI and EK (β=0.280, ΔR2=0.007, F=2.14, p > 0.05). Hence, H3a was not supported. However, in-class activities (Model 5) had a significant interaction effect (β=0.254, ΔR2=0.021, F=6.09, p < 0.05), thus supporting H3b and accounting for 2.1 % of the explained variance in students' EK. Similarly, Model 6 revealed that assessments significantly increased the explained variance in students' EK by 2.4 % (β = 0.300, ΔR2 = 0.024, F = 7.65, p < 0.01), thereby supporting H3c.

To deepen our understanding of these relationships, we conducted simple slope tests to plot the interactions in terms of unstandardized β coefficients (Aiken et al., 1991). This process involved splitting the moderators into high (i.e., one standard deviation above the mean) and low (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean) groups to reassess this relationship. The three plots presented in Fig. 2 depict the interaction effects. Overall, assessments were characterized by a more significant and stronger interaction effect than were other pedagogical approaches. Moreover, since we included nine types of assessments in our analysis, it was instructive to determine which assessment type contributed most effectively to students’ EK. As indicated in Table 6, the mean scores and t test results revealed that ‘case studies’ (t = 3.758**) had the most significant impact on students’ EK, followed by ‘new business pitch presentations’ (t = 3.665**), ‘individual reports’ (t = 2.266*), ‘class participation’ (t = 0.602 ns), and general ‘presentations’ (t = 0.490 ns).

Assessment types.

| 95 % confidence interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessments | Mean | SD | t | Lower | Upper |

| Case study | 5.39 | 1.482 | 3.758&#¿;&#¿; | .19 | .60 |

| Individual report essay | 5.25 | 1.544 | 2.266* | .03 | .46 |

| Group report | 4.73 | 1.745 | -2.177* | -0.51 | -0.03 |

| Presentation | 5.06 | 1.697 | .490 | -0.18 | .30 |

| Recorded video presentation | 4.96 | 1.717 | -0.302 | -0.28 | .20 |

| New business pitch presentation | 5.40 | 1.537 | 3.665&#¿;&#¿; | .18 | .61 |

| Online discussion forum | 4.55 | 1.763 | -3.624&#¿;&#¿; | -0.70 | -0.21 |

| Class participation | 5.08 | 1.773 | .602 | -0.17 | .32 |

| Examination | 3.96 | 2.034 | -7.251* | -1.33 | -0.76 |

Note.

We used the bootstrapping technique with the assistance of PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to test the mediating role of EE in the relationship between student EI and EK. We examined the bootstrap lower-level confidence interval (LLCI) and upper-level confidence interval (ULCI) for the direct and indirect effects (Cheung & Lau, 2008). The results indicated significant direct effects between student EI and EE (β = 0.34, p < 0.01, LLCI = 0.0907, ULCI = 0.5928) as well as between EE and EK (β = 0.18, p < 0.01, LLCI = 0.0590, ULCI = 0.3115). Moreover, the indirect effect between student EI and learning through EE was significant (effect size = 0.063, LLCI = 0.0085, ULCI = 0.1435), thus supporting H2. These results provide evidence indicating the presence of significant partial mediation in this context; i.e., both the direct and indirect effects are significant (Cheung & Lau, 2008). Thus, EE partially and significantly mediates the positive impact of students' EI on EK.

Post hoc analysisWe compiled participants’ responses to the open-ended survey question regarding the pedagogical modules that inspired the students and enhanced their EK. These open-ended responses served as additional data from which we could obtain further insights and on the basis of which we could substantiate our quantitative analyses. A vast majority of participants who responded to this question identified the ‘new venture pitch’ assessment as the most significant predictor of EK. Some participants indicated that writing a business plan was more insightful, while others focused on content delivery that led them to introspect and consider hidden leadership traits that could strengthen their core skills. The group assessment or tasks that asked students to work on a professional team also inspired many students. The students’ responses clearly revealed that these assignments enabled them to apply theory to practice, thus enhancing their EK. Students’ responses also highlighted the importance of in-class activities. Their quotations reveal that innovative in-class activities such as TED talks, interviews with entrepreneurs, success stories, and case studies inspired students to start new ventures. Indeed, many students claimed that the case study discussions exposed them to new opportunities to become entrepreneurs. Some participants viewed the class presentations as effective tools that could prepare them to take on leadership roles in the future. The students also found lectures to represent a useful pedagogical approach. More specifically, lectures by guest speakers and those that facilitated discussion concerning the entrepreneurial process and emphasized social entrepreneurship were viewed as more inspiring by students. Illustrative quotations from students are presented in Appendix A to provide insights into the ways in which students view the ability of different pedagogical approaches to enhance their EK.

Discussion and contributionsThis study aims to investigate the pedagogical approaches that can be used to inspire students to learn in the context of an entrepreneurship course. We posit that when students enroll in an entrepreneurship course, this behavior expresses their EI, namely, the desire to become an entrepreneur. Established constructs developed by Liñán and Chen (2009) were used to measure EI and EK, and constructs pertaining to inspiration that were drawn from Souitaris et al. (2007) were used to operationalize EE. Our results indicate that students who both exhibit positive personal attitudes and EI and who invest in EE are likely to be inspired to engage actively in their entrepreneurship learning and to obtain better EK outcomes. Our findings, which build on the work of Kautonen et al. (2015), Turner and Gianiodis (2018) and Fayolle and Gailly (2015), reveal that positive personal attitudes and EI are likely to improve student outcomes. The opportunity to increase EK extends beyond the level of subject content. Rather, it emphasizes the importance of fostering and developing EI among students with the aim of encouraging them to be entrepreneurs, to found new business ventures and to take control of their own futures. Encouraging entrepreneurship is relevant for developed economies that feature supportive entrepreneurial ecosystems as well as for less developed economies, in which entrepreneurship is a crucial driver of economic growth (Acs et al., 2016; Aljohani et al., 2022).

The significant effect of EE on EK highlights the crucial role influence of pedagogical approaches on students’ learning experience (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008; Haddad et al., 2021). In addition to this significant direct effect, EE plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between EI and EK. The three pedagogical approaches to EE on which our study focused include lectures, in-class activities and assessments. Our findings suggest that practical inspiration can be the result of practical assessment (Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022). In contrast to Farashahi and Tajeddin (2018), we reveal that the theoretical inspiration associated with theoretical pedagogy, such as lectures, conferences and the development of an interest in research, is less impactful with respect to students’ learning experience. Our findings provide much-needed clarity regarding the ways in which entrepreneurship curricula and pedagogical methods can positively impact entrepreneurial behavior (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Kwong et al., 2022; Nabi et al., 2018; Padilla-Meléndez & del-Aguila-Obra, 2022; Sherkat & Chenari, 2022).

An exploration of the mediating role played by EE in the relationship between EI and EK reveals that while lectures are directly related to students’ EL, the interaction between lectures and EI does not significantly impact EK, thus suggesting that while lecture content provides basic EE knowledge as part of the learning process, more than basic knowledge is required to inspire students to engage in entrepreneurial learning and acquire EK. Our data suggest that assessments that require less interaction and that focus on theoretical content, e.g., recorded video presentations, online discussion forums, and examinations, have weaker impacts on EK (Grimley et al., 2011; O'Connor, 2022). We find that constructive in-class activities inspire students and impact their learning outcomes directly; these findings are consistent with the experiential approach to learning (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Johannisson, 1991; Johannisson et al., 1998; Taneja et al., 2023). This account of inspiration on the basis of constructive activities extends the research on experiential learning conducted by Blankesteijn et al. (2024) and Taneja et al. (2023), who examined various approaches to EI with respect to experiential learning. We find that activities that include a variety of forms of learning-by-doing through participation in case study discussions, roleplaying, suggestions for business ideas and several mock pitch presentations of business ideas can be used to promote EK.

The results pertaining to the third category, i.e., assessments, suggest that our examinations of pedagogical methods, which have typically included lectures and in-class activities (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018; Sherkat & Chenari, 2022), should extend to the ways in which we evaluate students. In our study, assessments were observed to be associated with more significant positive results than were lectures or in-class activities. Further investigation of different assessment types reveals that the pitch presentations for new businesses have the strongest impact on students’ learning, followed by the case study analysis and the individual essay. The feedback provided by one student illustrates this finding: “The assessment task that allowed us to work within a team in a professional environment on an idea that was our own was very inspiring. My career goal is to become an aspiring entrepreneur, and I was able to see the steps that I needed to take to get there” (see Appendix: Illustrative quotations from students regarding the pedagogical modules that inspired them and enhanced their entrepreneurial knowledge). While pitch presentations for new businesses and case studies require interaction with other students, the individual essay is an individual assessment. Nevertheless, this assessment requires students to interview a business owner and write an essay concerning the entrepreneurial journey experienced by that business owner. This activity-based pedagogical approach highlights various effective learning outcomes and indicates that practical and real-world assessments have the strongest impacts on EK, while passive and didactic teaching methods are less likely to inspire entrepreneurship students (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022; Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Johannisson, 1991).

First, our study highlights empirical evidence indicating that entrepreneurship can be taught, thereby contributing to the longstanding discourse concerning this topic (Drucker, 2014; Neck & Greene, 2011). Second, our study expands our understanding of the ways in which entrepreneurship can be taught by identifying various pedagogical approaches that influence learning outcomes pertaining to EK. We observe that pedagogical approaches that involve delivering content, e.g., via lectures, should be implemented alongside activity-based in-class activities and authentic assessments, as these approaches also play significant roles in students’ learning (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008; Knight et al., 2014). The acquisition of EK represents the foundation of innovative behavior, and it can inspire and facilitate the establishment of competitive start-up ventures (Adeel et al., 2023; Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022). Our third contribution indicates that not all pedagogical approaches have the same effects on students’ learning, and a deeper investigation reveals that the use of assessment as a pedagogical approach has the most significant effect in this context, followed by in-class activities and lectures. The strong positive impact of assessment in this context can be attributed to the design of such assessments. Assessments that require students to engage in active learning by participating in various activities, such as delivering pitch presentations, conducting interviews with entrepreneurial business owners, and critically analyzing the entrepreneurial journeys of business owners, extend beyond the mere acquisition of knowledge to inspire students to become entrepreneurs (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Kolb & Kolb, 2005; Mukesh et al., 2020; Taneja et al., 2023).

Implications of our studyOur study highlights the fact that the efficacy of EE can be enhanced when students engage in active, hands-on learning experiences within the classroom (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Mukesh et al., 2020; Nabi et al., 2018). While students are central figures with respect to their own EE, our research also has implications for various stakeholders, including educators, academic institutions, and government agencies, that recognize the vital role played by EE in the process of nurturing future entrepreneurs within the community. The impacts on these stakeholders indicate that our study has both theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implicationsIn light of the fact that ‘entrepreneurship is teachable’ (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Drucker, 2005; Neck & Greene, 2011; Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021), education theorists have emphasized the ways in which entrepreneurship is taught in the classroom (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Haddad et al., 2021). Moreover, several empirical studies have reported that EK can significantly enhance students' entrepreneurial characteristics (Lin et al., 2024; Politis, 2005; Scuotto & Morellato, 2013). Accordingly, business schools have attempted to advance various pedagogical approaches to EE with the aim of enhancing learning outcomes among entrepreneurship students (Haddoud et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023). Educators have used different teaching methods and content to enhance students’ entrepreneurial capability and to inspire students to engage in entrepreneurial learning (Fayolle et al., 2006; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022). Our study makes three important contributions to this stream of research.

First, we extend entrepreneurial inspiration theory (Li et al., 2023; Souitaris et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022) by developing a conceptual framework that can be used to investigate the mediating effect of EE on the relationship between EI and EK, in which context we reveal a positive link. Theoretical inspiration in the context of EE is evident in various pedagogical approaches, including lectures, guest speakers, tutors, case studies, in-class activities and assessments (Biggs & Yang, 2011; Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Nabi et al., 2017).

Second, in contrast to previous studies that have viewed lectures as a critical source of EE (Grimley et al., 2011; O'Connor, 2022), we did not find that lectures play a significant role. Instead, we observed that assessments significantly and positively impact students’ EK. We empirically demonstrated that assessments occupy an important position among three frequently used pedagogical approaches in business schools: lectures, in-class activities, and assessment methods (Biggs & Yang, 2011; Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Nabi et al., 2017). One reason for this finding could be that assessments that require students to apply what they have learned in class can inspire them to construct new knowledge of entrepreneurship in a creative manner.

Finally, we contribute to the discourse concerning the teachability of entrepreneurship (Allal-Chérif & Bidan, 2017; Nabi et al., 2017) by exploring the mediating role of the relationship between EI and EK in the context of EE and by revealing the significant and positive direct and indirect effects of EE on the relationship between EI and EK.

Practical implicationsOur findings have significant implications for entrepreneurship educators seeking to design effective EE programs to instill EK in students and others who intend to become entrepreneurs and start new ventures as a viable career choice. Entrepreneurship educators must consider innovative pedagogical approaches that involve experiential, authentic in-class activities and assessments. Our data indicate that EK improves when entrepreneurship students engage in active, hands-on learning experiences within the classroom, thus supporting the claims of previous researchers (Blankesteijn et al., 2024; Mukesh et al., 2020; Nabi et al., 2018). Under the guidance of policymakers, academic institutions should support educators through recruitment policies and training initiatives that emphasize soft skills and social constructivist learning approaches. In the context of such methods, the educator acts as a facilitator and focuses more closely on students’ efforts to solve applicable business problems in the real world while working alongside their peers (as opposed to a traditional chalk-and-talk approach) (Aljohani et al., 2022; Kolb & Kolb, 2005). Educators must be mindful of the need to adapt their curricula to suit different cultural contexts, such as by integrating indigenous knowledge and incorporating other cultural and social norms (Welter, 2011). EE should be extended beyond the level of business schools to encompass students from diverse disciplines, thereby establishing a culture that focuses on the creation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Encouraging extracurricular activities and establishing student entrepreneurship clubs can help cultivate a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem (Huang et al., 2023; Padilla-Meléndez & del-Aguila-Obra, 2022). Entrepreneurs have been widely acknowledged as catalysts for economic growth, who can thus help generate new knowledge, promote innovative behavior and provide employment opportunities (Acs et al., 2016; Aljohani et al., 2022). While institutional and regional contexts might be relevant in this context (Spigel, 2017), governments can actively enhance this economic advantage by establishing an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Such an ecosystem can be created through the provision of funding and incentives for innovative products and services and, indeed, through the provision of internal incentives or collaboration with external incubators and accelerators, thus providing further inspiration for students’ EI (Huang et al., 2023; Padilla-Meléndez & del-Aguila-Obra, 2022).

Limitations and directions for future researchThis study has several limitations that can provide insights to support future research in this area. First, our use of cross-sectional data limits our ability to establish causal relationships. Future researchers in this stream should use longitudinal data that can track the temporal associations among EI, different pedagogical approaches, and EK to establish causality over time. Additionally, we focused primarily on short-term effects; in contrast, longitudinal studies can reveal various long-term impacts on students' entrepreneurial pursuits beyond the level of academia. Second, our data (Table 6) suggest that some types of assessment are negatively related to EK. Examples include ‘online discussion forums’ (t = -3.624**), ‘group reports’ (t = -2.177**), and ‘examinations’ (t = -7.251*). These findings might be due to the institutional factors that impact this research since we collected all the data at the same business school.

Moreover, our sample is limited to students majoring in entrepreneurship and leadership. However, some students might be studying for dual majors. Future researchers could collect data from a broader sample to provide a more nuanced understanding of the conditions under which some assessments can be less effective in terms of their ability to enhance EK. Third, our survey asked open-ended questions but did not sufficiently reflect students’ experiences. Future researchers can use in-depth interviews or mixed-methods approaches to improve our understanding of the relationships hypothesized in this study. Finally, investigating the ways in which the pedagogical approaches included in this study influence knowledge acquisition among students in related disciplines such as strategy, marketing, and international business would be helpful. Such a cross-disciplinary investigation could increase the generalizability of our findings to encompass other business faculties.

Additionally, our study focused primarily on short-term effects; accordingly, long-term follow-up studies can reveal the sustainability of these approaches and their impacts on students' entrepreneurial pursuits beyond the context of academia. Finally, we must recognize the transformative potential of large language models in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), which give rise to various challenges and opportunities for EE, businesses, and diverse fields of research.

ConclusionTheorists and educators who have focused on EK have explored different pedagogical approaches that can be used to improve learning outcomes among entrepreneurship students. This study empirically examined the moderating role played by pedagogical approaches in the relationship between EI and EK. Our study highlights the direct positive impact of EI on EK as well as the vital role played by the pedagogy employed in EE in this context. While previous studies on EE have focused mainly on the relationship between EE and EI, our study examines the role played by EE in the acquisition of EK. Specifically, we investigate the ways in which the different pedagogical approaches used in EE influence students’ ability to acquire EK. We find that some pedagogical approaches inspire students to learn more effectively, such that students perceive that they have acquired EK. While lectures and in-class activities are essential to students’ EK in their own right, assessments play the most significant role in this context. Our analysis identified various specific elements of assessments and in-class activities that can significantly strengthen the influence of EI on EK. Inspiring assessments in the context of EE focus on actively impacting students’ learning and their ability to acquire knowledge. In our study, the assessments associated with practice-based case studies, interviews with entrepreneurs and a team project that involved pitch presentations and a start-up business plan were all identified as activity-driven assessments that required students to apply the knowledge that they had learned in class.

These findings provide valuable guidance concerning effective EE and can be used to design tailored interventions that can help improve students' entrepreneurial skills and competencies. These findings have significant implications for future studies on ways of enhancing students’ EK. Although this research had certain limitations, we hope that it has laid a foundation for future research on the ways in which the pedagogical approaches used by business schools can be redesigned to impart knowledge and that it can continue to inform both theory and practice.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFrances Y.M. Chang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Muhammad Aftab Alam: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. Murray Taylor: Writing – review & editing.

The authors would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief and the reviewers for their generosity of time and insightful comments which have greatly improved our paper.

| Illustrative quotations | |

|---|---|

| Lectures |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| In-class activities |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Assessments |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|