Implantation of the smart city model in intermediate tourist towns on their transition to becoming smart destinations involves an inescapable commitment to their habitat and improving the quality of civic life and the economy of cities through more sustainable and technologically advanced elements. Based on this work, the aim is to achieve an overview of the current smart cities paradigm from the standpoint of territorial interest groups, by analysing a tourist town on the Mediterranean coast (Gandia, Valencia) to diagnose its current status. The ultimate aim is to answer the question of whether these intermediate tourist cities are in a position to align themselves with the necessary requirements of the smart model, in their transition to becoming smart tourism destinations.

For several years, tourism has undergone continuous growth. Its intense diversification makes it an increasingly globalised, competitive sector with ongoing innovation needs. So, it is no coincidence that it has become one of the major economic growth sectors worldwide. Tourism is currently strongly linked with development, as its dynamism has helped convert it into a capital sector for social and economic progress. In an increasingly globalised and competitive context, it is up to the management of tourist destinations to develop innovative and sustainable strategies to ensure the best possible results over time. Innovation in the tourism sector is linked to the use of information and communication technologies (henceforth, ICT), which has transformed the sector's modus operandi through mutability in the forms of organisation, processes and products of companies providing tourism services, as well as the new consumer-tourist demands.

ICTs currently play an important role in any area of society and specifically in any of those making up the tourist sector. The digital-technological revolution and the impacts of ICTs in the tourism sector highlight the importance of investing in the most appropriate and current technological applications in companies providing tourist services (Ruiz & Hernández, 2017). Moreover, according to Buhalis (2003), ICTs incorporate a whole series of electronic instruments that facilitate the operational and strategic management of institutions and companies in matters such as information and knowledge management, as well as communication and interaction with interest groups (stakeholders). We are indubitably facing a digital revolution that has substantially modified tourism management (Gretzel et al., 2000).

The universality of ICT in the tourism sector “in terms of supply (mainly management and marketing) and demand (information, reservation, purchase and tourism experience) blurs the distinction between online and offline processes” (Ivars et al., 2016:331). ICTs have thus provided new tools for the tourism industry, giving rise to new experiences for tourists. Likewise, the swift uptake of mobile technologies by tourists and visitors has enabled travellers to consume individualised information, regardless of the site and situation in which they are located (Lamsfus et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2012). Many works in the scientific literature point to the inescapable importance of ICT in tourism and technological-digital innovation of tourism sector organisations (Buhalis, 2003, 2013; Cerezo & Guevara, 2015; Gretzel et al., 2000; Lamsfus, 2014; Parra & Santana, 2014; and Ruiz & Hernández, 2017, among others). So, from this technological perspective, we can deduce that tourist destinations, through both public and private sectors, should invest in ICTs to hone their competitive edge and improve their management.

Focusing on this context, characterised by the intensive use of information and technological evolution, ICTs enable new services and the reconversion of traditional ones through the adoption of new ideas and approaches to tourism development. This is where the proposal for smart tourist destinations, mainly arising from the smart city concept, has acquired undeniable media, programmatic and academic validity. This latter concept reflects the emerging nature of cities that apply ICT and knowledge management to improve the quality of life of city dwellers and sustainable civic development, under the auspices of participation, collaboration and innovation, with a certain emphasis on adaptation to the digital economy, defined as a renewed archetype of urban planning and management for 21st century cities.

This work aims to achieve a current vision of the smart cities paradigm from the standpoint of territorial interest groups, based on the case study analysis of a tourist town of the Mediterranean coast (Gandia, Valencia). We attempt to analyse the case history of smart tourist destinations (STDs), with the aim of finally answering whether these intermediate tourist cities are in a position to align themselves with the necessary requirements of the smart model in their transition to becoming STDs.

Theoretical frameworkThis section is divided into three subsections. The first defines the smart city concept in terms of the intermediate cities model. The second gives an account of the basic pillars of the smart archetype (or Smart Tourist Destination when the focus is on tourism development). Finally, we explain the crucial role of interest groups within the framework of the aforementioned archetype.

The smart city in intermediate citiesFor some years now, the smart city has been cited as the new archetype for urban development. Indeed, the discourse-proposal notion of the smart city greatly influences the media and institutional affairs – this has gradually become embedded in the programmes and agendas of institutional urban policies – in addition to academic issues. The cited concept has several definitions, although among the most commonly accepted by the scientific community is that put forward by Caragliu et al. (2011), who defined the city as smart when social investment, human capital, communications and infrastructures coexist in harmony with a view to promoting sustainable and efficient socioeconomic development, relying on the use of ICT to this end.

Achieving cities that work in a sustainable and integrated manner is one of the main challenges of the twenty-first century as their position as epicentre of urban life is reinforced. According to data from the United Nations, 2 out of 3 people will be living in cities by 2050. The same source points out that in Europe, 7 out of 10 people reside in cities, and foresees that this figure will rise. In the case of Spain, the UN estimates that 40% of the Spanish population will be living in 15 cities of more than 300,000 inhabitants (United Nations, 2018). Certainly, the increase in the degree of urbanisation tentatively reveals the main challenges to which local governments must respond with sustainable urban planning, which in turn should generate economic opportunities. This calls for better deployment of public resources and a responsible use of natural resources to optimise the uses of transport and infrastructure, preserve and increase energy efficiency, ensure accessibility of services and be vigilant towards the environment. The idea of the smart city thus emerges as a city that exploits the capabilities of technology to optimise sustainability and improve people's quality of life. The notion of an interconnected future where all the information gathered is measured, processed and analysed in order to improve the use and efficiency of the resources and services that are provided, thus contributing to the most appropriate decision-making.

However, the highly complex urban structure that has long been associated only with large cities has changed with the new demographic, as urban settlements of this kind have slower population growth rates than other relatively smaller urban centres (Bouskela et al., 2016). Thus, intermediate cities have also grown at an accelerated pace. Although the term intermediate city can give rise to diverse interpretations, a traditional delimitation in line with the UIA-CIMES1 programme is based on its size. Thus, following the norm of the European context, the range is delimited between 20,000 and 500,000 inhabitants. However, intermediate cities cannot be delimited exclusively based on variables such as demographic size or geographical area. The most appropriate approaches at territorial level go beyond the classical ways of classifying and delimiting intermediate cities, by mainly focusing on the intermediary functions performed by this type of cities in the territory and their vocation to articulate specific spaces with other nodes and territories in the local and regional scope.

Along this line, more than half of the urban population of the planet lives in intermediate cities and the accelerated growth observed in them can affect the sustainability and quality of life of their inhabitants (UCLG, 2017). The European Territorial Strategy (1999) acknowledges the importance of developing a more balanced and orderly European urban system, able to generate a polycentric development in order to assure the delivery of resources, services, employment and innovation to the majority of the population through city networks, while also seeking greater territorial cohesion (Romero & Farinós, 2004). Thus, the intermediate cities that fulfil functions as regional capitals take on an essential role in these areas and are important centres for the development of industrial activities and services, research and technology, tourism and leisure (European Commission, 1999). Many of these intermediate cities act as functional hubs for areas consisting of other cities and towns, and delimited by criteria such as the movements of people, urban expansion, the provision of supra-municipal services and public transport corridors, and which articulate the territory comprehensively. These areas should also therefore be subject to territorial management and planning if the smart city approach is to be applied in these towns, and especially if they are also poles of tourist attraction. The territorial dimension and the policies that are applied can influence the dynamics of organisational innovations in the tourism sector (and related areas) and help build innovation systems (Zach & Hill, 2017).

Smart tourist destinationThe concept of an intelligent tourist destination ultimately arises from the notion of smart cities (Ivars et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2014), but focusing more on tourism development. In the tourism scope, smart cities present new challenges while providing new service and business opportunities. To be able to better adopt the smart structure in cities where the tourism sector is the economic driving force, the so-called intelligent destinations have been dubbed Smart Tourism Destinations. According to López de Ávila et al. (2015:32), a smart city is defined as a “tourism-oriented and innovative space accessible to all, which is consolidated on a cutting-edge technological infrastructure, which must guarantee sustainable territorial development while facilitating visitor interaction and integration with the environment, increasing the quality of their experience in the destination and the quality of life of the residents.” Thus, the authors who have so far addressed the conceptualisation of STDs point to the features of “Smart Cities” in their line of argument as a necessary prerequisite for the emergence of STDs (Lamsfus & Alzua-Sorzabal, 2013; Zhu et al., 2014).

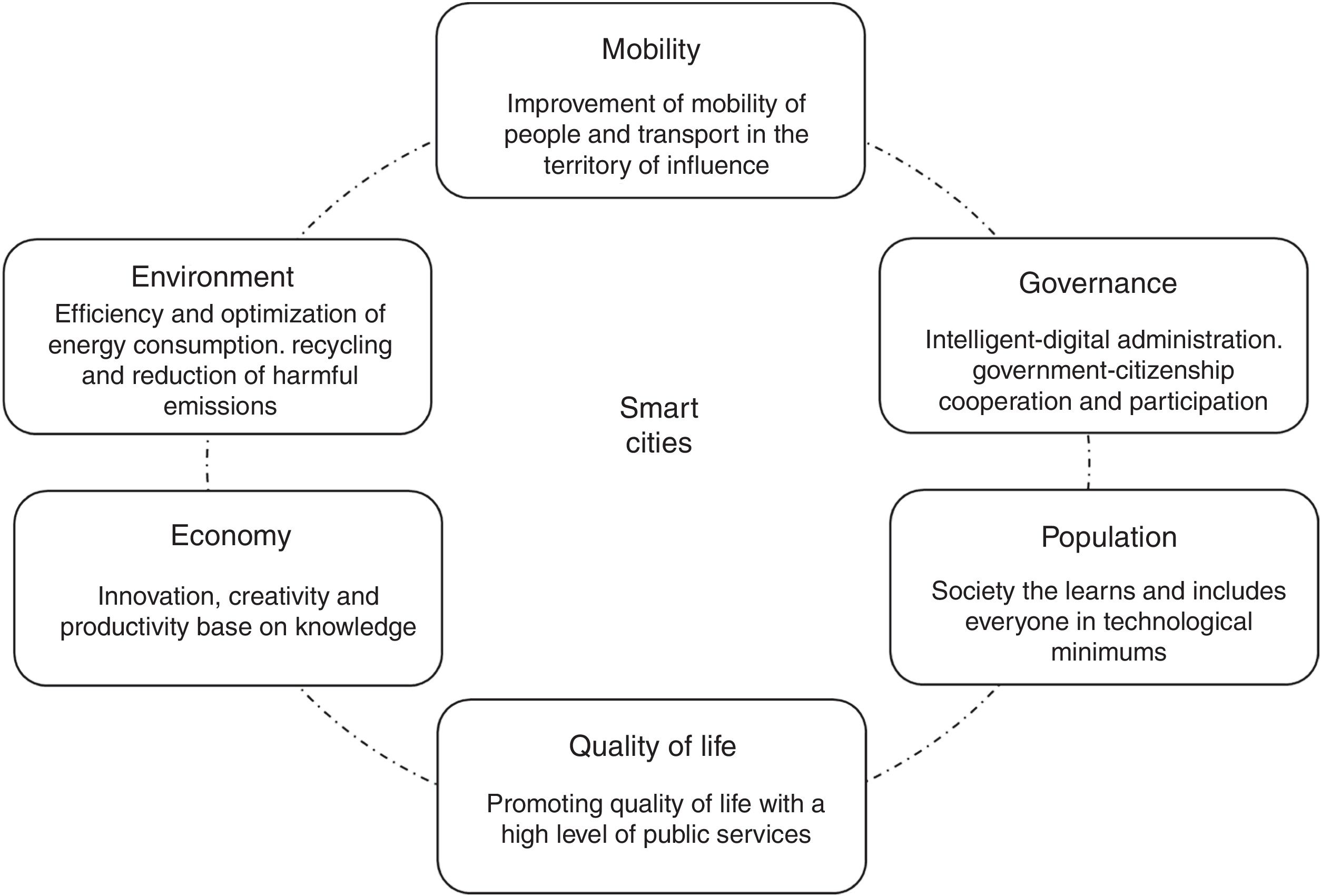

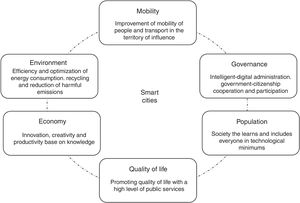

The smart city has become common ground for the urban discourse whose tenet has been received with enthusiasm in the media, institutional and academic sphere. But this ideal city entails considerable challenges. Many of these hurdles are linked with the 6 dimensions or pillars posited by the model: population, environment, mobility, economy, quality of life and governance (Enerlis et al., 2012; Giffinger et al., 2007; Giffinger & Gudrun, 2010); as shown in Fig. 1.

The dimensions (pillars) of smart cities.

Source: Own creation, adapted from Giffinger and Gudrun (2010).

In line with the above, the core of the discourse proposed by this urban model is that the techno-smart city will improve the quality of life of cities, charting the path towards change in the socioeconomic structure of cities, based on the capacity for omnipresent connection and information sharing, being proactive with our environment and protecting the sustainability of the habitat. So, a smart city must be specially enabled for the use of ICT, designed to improve competitive edge and sustainability based on the interconnection and exchange of information between people, companies, institutions, infrastructures, energy, consumption and the different services and spaces that make up the urban environment or habitat. In the sense, we agree with Guo et al. (2014), when stating that STDs ultimately depend on the city's technology infrastructure and the interchanges and uses made of information resources and the processing of data intelligence.

In this sense, the implementation of ICTs in this concept of city is crucial to be able to capture the data related to tourism and the data left by tourists visiting the place, with a view to providing services in real time and personalised, while leveraging them to optimise strategic management that will help improve the tourist experience in the town. Technological innovations also lay the foundations for new tourism experiences (Hjalager, 2015). For Segittur (2015), the intention to evolve towards STDs involves setting out a strategy to reassess the destination, which will help boost its competitive edge by making better use of its strengths, creating innovative resources, enhancing the efficiency of production processes and a distribution that finally addresses sustainable development in order to facilitate visitor integration in the destination. ICTs are a key factor in transformation of the tourism industry, contributing to management of the city and destination through intelligent technologies, thus aligning with smart model approaches (Invat.tur-Valencian Institute of Tourism Technologies, 2015). In this context, the propagation of mobile telephony and its different applications also plays an important role (Kim & Law, 2015; Lamsfus et al., 2015).

As highlighted by López de Ávila and Sánchez (2013), an STD is considered an innovative space based on the territory and a state-of-the-art technological infrastructure, committed to sustainability and with the socioeconomic and cultural singularities of the habitat, equipped with an intelligence system able to effectively capture, analyse and interpret information in real time, thus encouraging interaction between visitors and their surroundings and enriching the quality of tourist experiences. So, in this complex context the STD requires the joint and coordinated action of both the private and public sectors to draw up an integral action plan -or master plan-, as the urban question merits diverse and plural scrutiny (Monnet et al., 2013), given the qualities that each discipline or scope of knowledge can contribute, without exclusively circumscribing strictly touristic aspects. Although ICTs and advanced technological innovations provide the essential substrate for the development of STDs, this alone is not enough.

Interest groups in the smart model frameworkIn this sense, advancing towards becoming an STD should be a collective and shared task, involving both local institutions and tourism companies as well as society on the whole, including tourists; in short, those who are its true protagonists (Hernández, 2007; Fernàndez, 2014). Management and urban planning of the model should mainly concentrate on the human issues of urban habitat, rather than focusing exclusively on the technocratic vision of urban-technological planning and the accumulation of technologies, the result of which would be a more marketing-oriented model rather than a functional-pragmatic approach. In this line, we are generally faced with rather uncritical institutional discourse regarding the idea of the smart approach and the consequent technological deployment in cities, due to the question: Who could be against this ideal? “Smart” projects of this nature unavoidably call for the participation of interest groups in their determination to solve the real problems of the urban habitat, above all, if they intend to satisfy the consumers and be sustainable in the long term. Although there are abundant studies in the scientific literature based mainly on the importance of the use of ICT as a smart tourism resource (Wang et al., 2012), there is still a lack of research that explains the phenomenon in a more systematic and global way (Ivars-Baidal et al., 2018).

Tackling the challenge of smart cities necessarily involves participation of the different stakeholders, which constitutes one of the main elements to achieve governance in cities (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2014; Díaz, 2017; Fernández Alcantud et al., 2017; Gómez & Martín, 2015; Santos-Júnior et al., 2016; Tomàs & Cegarra, 2016). The plurality and complexity of urban habitats has motivated many studies aimed at identifying stakeholders to account for their classification and the interactions that occur between them (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Khomsi & Bedard, 2017; Liu, 2003), which is why we find as many classifications as there are studies on the subject. Nevertheless, the review of the scientific literature identifies a typology common to all classifications in terms of who the smart city stakeholders are: the public sector, the private sector, civil society, and, in the case of tourist cities, the tourists themselves. Defining a city's transition to becoming a smart city requires new ways of delimiting government action and new operative models between the actors and administrative levels of government involved in the decision-making process regarding urban policies with an impact on the territory.

In recent years, city planning and management has hinged around the notion of governance as a new process of governing to the detriment of the classical notion of government as a nuclear agent (Aguilar, 2010), a question that reminds us that the society we live in is a public reality that everyone understands and is involved in, which therefore must be the result of a collective project. In this line, in recent decades, in the context of the formulation of public policies among the actors and the different levels of administration, these changes have been reflected in the manner of governing with a more open, decentralised style of government, less hierarchical, more horizontal and accessible (Hall, 2011; John, 2001). Efforts are made to incorporate the different interest groups in the debate on public issues in the territorial scope, which entails a process of participation and coordination of the actors in objectives that must be determined collectively (Le Galès, 2004). However, such an ideal of governance may be too idyllic a vision. It probably is. In this sense, authors such as Kübler and Wälti (2017) consider that in this kind of ideal of governance, citizens have greater power in the decision-making processes, evidencing a clear optimism. In contrast, other authors such as Stone (1989) highlight an opportunity for the private and particular interests of private companies and organisations under this new governance. Whatever the case, and despite the obstacles to be overcome, the current context of governance and the attempt to move towards an intelligent tourist destination requires the creation of a “touristic” governance through public-private collaboration and the community as an essential element (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2014; Cambrils, 2015; Sigalat et al., 2018b), in addition to management support from local government.

MethodologyThis work is contextualised in the tourist town of Gandia (Valencia), which is currently working on the transitioning process to become an innovative, accessible and consolidated tourist destination based on a state-of-the-art technological infrastructure.2 The research is exploratory and descriptive, designed to integrate the theoretical-conceptual approaches to smart tourist destinations and give an account of their applicability through the case study of the aforementioned destination.

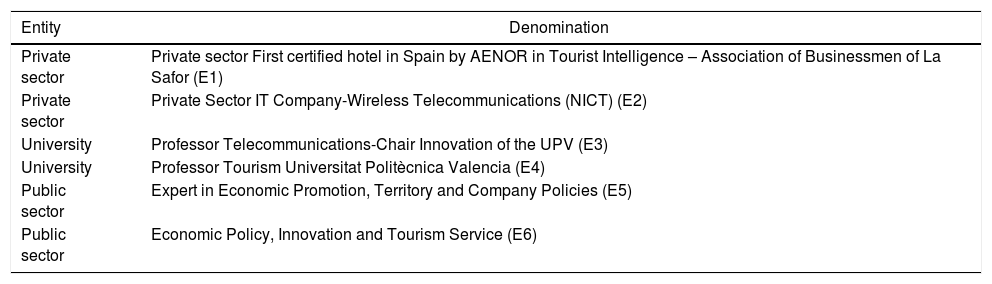

On the one hand, the methodology used to achieve the objectives deals with the bibliographical perspective, seeking out and reviewing documentary sources of scientific information, as well as statistical sources from agencies and official public entities, and on the other, in a complementary way, semi-structured interviews with key actors in the city's tourism, as well as direct observation of the study area. We examine the features of the methodology developed by Invat.tur through the Office for Technical Assistance to Smart Tourist Destinations of the Valencian Community (STD CV) which is connected with the 6 essential pillars – or dimensions – discussed above proposed by the smart approach (Giffinger et al., 2007; Giffinger & Gudrun, 2010), and which constitutes the interview model applied to the stakeholders to elicit their opinions3 on the destination (Table 1).

Entities interviewed.

| Entity | Denomination |

|---|---|

| Private sector | Private sector First certified hotel in Spain by AENOR in Tourist Intelligence – Association of Businessmen of La Safor (E1) |

| Private sector | Private Sector IT Company-Wireless Telecommunications (NICT) (E2) |

| University | Professor Telecommunications-Chair Innovation of the UPV (E3) |

| University | Professor Tourism Universitat Politècnica Valencia (E4) |

| Public sector | Expert in Economic Promotion, Territory and Company Policies (E5) |

| Public sector | Economic Policy, Innovation and Tourism Service (E6) |

Source: Own creation.

The selection process for the interviewed informants was not casual, as they are key actors due to their knowledge and direct involvement in the development and adaptation of the town to the smart tourist city model. These are informants who, from the public, private and academic sphere, are participating in the developments carried out so far and can provide first-hand information on the progress made. The research is presented as a qualitative case study based on the analytical commentary on basic data and, particularly, on application of the interviews with the key informants cited. To this end, the aim is not to conclude with by establishing generalisations, but rather to reach an analytical approach to the understanding of the reality under analysis.

ResultsThis section contains two subsections. The first characterises the relevant information on the municipality under analysis, while the second gives an account of the stakeholders’ vision of the transition towards becoming a smart tourist destination.

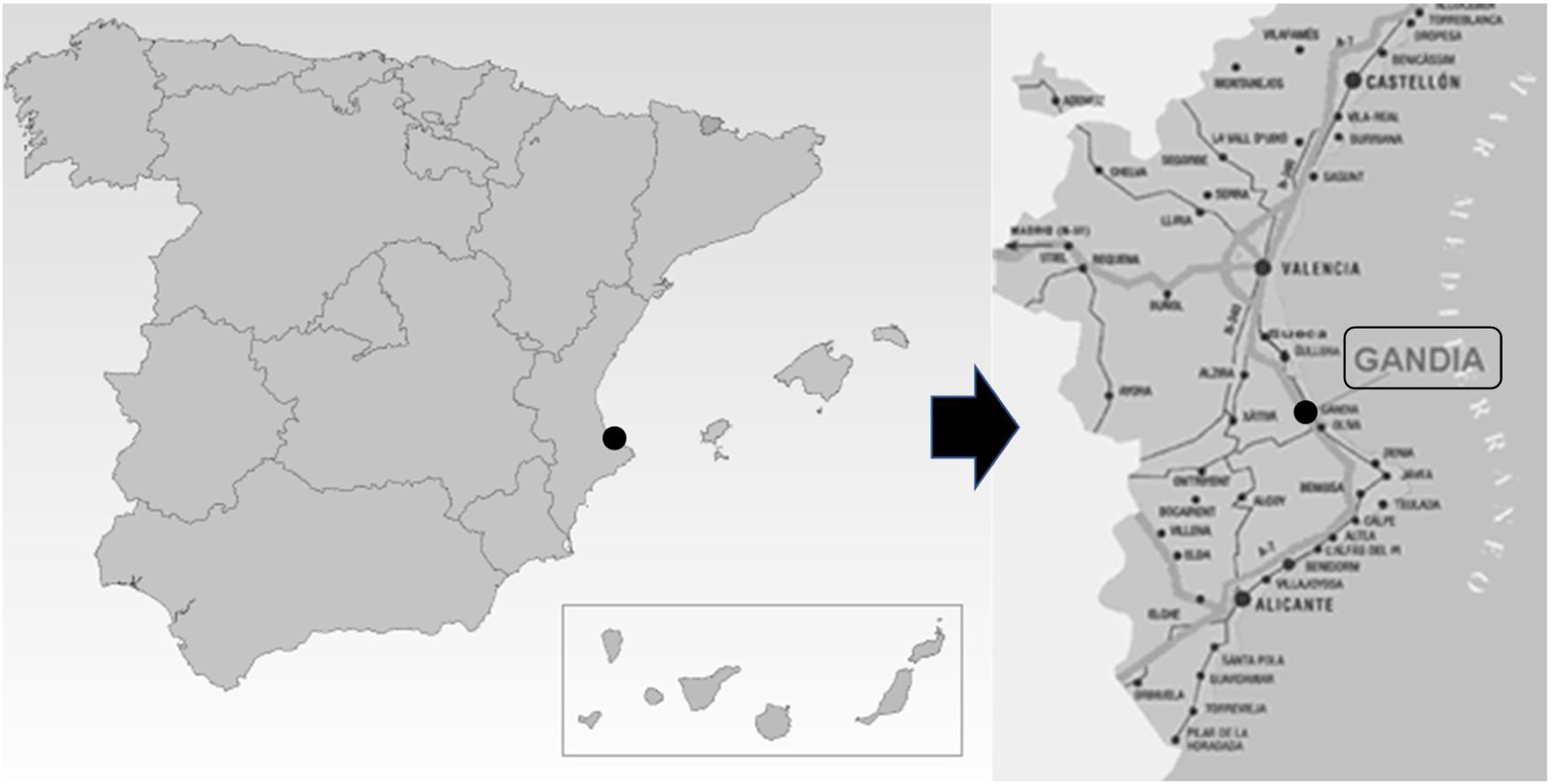

Destination characterisationGandia is a town and municipality in the southeast of Spain, located on the coast of Valencia province, in the Valencian Community. It is the capital of the La Safor region, located 65km south of Valencia (Fig. 2). The municipal area is located in the heart of the district, with a population of 73,289 inhabitants (INE, 2019), although it is estimated that its floating population is around 100,000–120,000 people, ranking as the seventh most populated city and one of the most important in Valencian territory.

The city is between the Mediterranean Sea and a surrounding mountainous belt. Its municipal jurisdiction covers an area of 61.5km2 with three population centres: Gandia town, the Grao de Gandia (port and beaches) and Marxuquera. The city is a tourist destination that combines beach with natural and mountain areas; leisure alongside culture, history and commerce; a varied offer of entertainment and relaxation. There is more than 5km of coastline and over 500,000m2 of fine sandy beaches. The city also boasts 25 hotels and more than 5,200 hotel rooms, with over 8,000 regulated spaces in apartments and 1,700 in campsites. This accounts for a total of more than 15,000 accommodation places (INE and Turisme Comunitat Valenciana, 2019).

Since the 60s of last century, the city has become one of the main Valencian tourist destinations, reaching three times its population in high season, rising to 320,000–350,000 inhabitants in summer. A typical Mediterranean climate and a remarkable tourist infrastructure in the destination with recognised quality and environmental seals, along with good communications and accessibility, make up an attractive space for the visitor all year round. Thus, tourism has become the city's main economic driving force, an aspect that has brought with it the development of the services sector, which occupies almost 76% of the population (INE, 2019).

In this line, many intermediate tourist towns share characteristic elements in common (Sigalat et al., 2018a, 2018b), as does the city of Gandia. We highlight three main elements. The first is the shifting of their economies to the tertiary sector. The second consists of cities with tourist attractions beyond their beaches and good weather, for their historical-patrimonial, natural-landscape, cultural and leisure value, a capital element in tourists’ motivation to travel. In third place, they are usually destinations with a similar population size, which tend to triple their population in high season and with considerable intraregional tourism, with important travel flows that may be greater depending on whether or not they have certain infrastructures, such as motorways, railway, airport and marine transport connections, among the most notable.

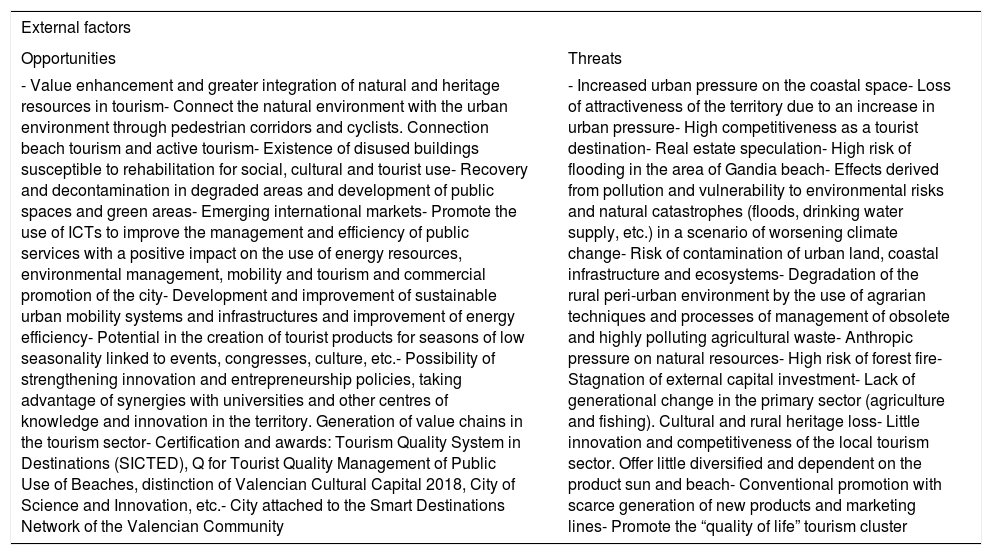

Finally, given all of the above, we should highlight that tourism is not a safe activity for the places where it is developed. Lack of planning for spaces can give rise to undesired impacts. In this sense, and in the context of becoming an STD, we reveal the positive and negative impacts of tourism, both internal and external, with reference to Gandia as a destination, through a SWOT analysis, in such a way that it furnishes us with basic information on the town's transformation to the propensities and requirements of becoming a smart tourist destination (Table 2).

Gandia city SWOT matrix.

| External factors | |

|---|---|

| Opportunities | Threats |

| - Value enhancement and greater integration of natural and heritage resources in tourism- Connect the natural environment with the urban environment through pedestrian corridors and cyclists. Connection beach tourism and active tourism- Existence of disused buildings susceptible to rehabilitation for social, cultural and tourist use- Recovery and decontamination in degraded areas and development of public spaces and green areas- Emerging international markets- Promote the use of ICTs to improve the management and efficiency of public services with a positive impact on the use of energy resources, environmental management, mobility and tourism and commercial promotion of the city- Development and improvement of sustainable urban mobility systems and infrastructures and improvement of energy efficiency- Potential in the creation of tourist products for seasons of low seasonality linked to events, congresses, culture, etc.- Possibility of strengthening innovation and entrepreneurship policies, taking advantage of synergies with universities and other centres of knowledge and innovation in the territory. Generation of value chains in the tourism sector- Certification and awards: Tourism Quality System in Destinations (SICTED), Q for Tourist Quality Management of Public Use of Beaches, distinction of Valencian Cultural Capital 2018, City of Science and Innovation, etc.- City attached to the Smart Destinations Network of the Valencian Community | - Increased urban pressure on the coastal space- Loss of attractiveness of the territory due to an increase in urban pressure- High competitiveness as a tourist destination- Real estate speculation- High risk of flooding in the area of Gandia beach- Effects derived from pollution and vulnerability to environmental risks and natural catastrophes (floods, drinking water supply, etc.) in a scenario of worsening climate change- Risk of contamination of urban land, coastal infrastructure and ecosystems- Degradation of the rural peri-urban environment by the use of agrarian techniques and processes of management of obsolete and highly polluting agricultural waste- Anthropic pressure on natural resources- High risk of forest fire- Stagnation of external capital investment- Lack of generational change in the primary sector (agriculture and fishing). Cultural and rural heritage loss- Little innovation and competitiveness of the local tourism sector. Offer little diversified and dependent on the product sun and beach- Conventional promotion with scarce generation of new products and marketing lines- Promote the “quality of life” tourism cluster |

| Internal factors | |

|---|---|

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| - Excellent location on the Valencian coast and geographical location on a climatological level.- Existence of a natural urban beach and forest in the same territory.- Consolidated destination of high quality in the provision of basic services.- Leads the Territorial Functional Area. It is the functional, economic, cultural and commercial centre of the La Safor region, with 31 municipalities and 170,686 inhabitants (INE, 2019).- Connected with the wide-track network that offers 42 daily trains with Valencia and allows direct connections with Madrid and Barcelona. Connection with AVE to Madrid (summer).- Existence of references and experiences of a strategic nature (Commercial Action Plan, Strategic Plan of Gandia 2025, etc.)- Existence of the port as an infrastructure and communication and transport hub.- Availability of a wide and rich landscape and ecological and archaeological patrimony (Marjal de Gandia, Serpis, Marxuquera, etc.) with a high value from the scientific, pedagogical, recreational and cultural point of view.- Growing environmental sensitivity among public officials and citizens.- Growing dynamism of the ecosystem system of local innovation, city recognised as a City of Science and Innovation (2010), and strengthened by the active presence of Valencian universities.- Potential for the presence of socio-institutional networks and associative fabric.- Productive model based on diversification and specialisation. Within this model, Gandia stands as an indisputable tertiary centrality.- Innovative pioneering experiences in the field of urban commerce. Gandia treasures the National Trade Award 2010. Dynamic, complementary and attractive commercial offer for the functional area.- Powerful tourist accommodation offer.- First European city that will control and manage its water consumption through Vodafone's narrowband IoT communication network (NB-IoT).- Two recent experiences of intelligent approach: one, the smart beaches design project carried out by the Tourism Agency of Valencia (through Invat.tur), and the second, the Action Plan for the improvement and the modernisation of the two main industrial areas of Gandia with the propensity to have an industry 4.0. | - Physical and functional disconnection between key vectors of development of the city: tourism (concentrated on the beach and Grao de Gandia), and the historical and commercial (concentrated in the Historic Centre)Access to the city of low urban quality and low attractiveness, inefficient from the point of view of mobility- Important bags of homes with more than 50 years old and with no energy efficiency- Lack of social, cultural and administrative facilities in Gandia beach- The car is the main mode of mobility in the city- High pressure on the environment and natural resources due to high noise pollution, high energy consumption of homes and lack of recycling of the organic waste- Gaps in the Urban Transportation system, disjointed with low use in new information technologies- Overexploitation of aquifers due to high extractions in the private sphere- Lack of dissemination of participatory processes and difficulty in reaching all sectors of the population- Public-private cooperation deficit in tourism management and promotion- Low governance in tourism (beyond the specific contributions of the Tourism Board of the city)- Little investment in R & D & I projects: partnerships of the private sector with universities, knowledge centres, etc.- Business economic structure based on SMEs- Deficient provision of technological and energy infrastructures that limit growth- High degree of tourist seasonality. Negative implications in the labour market- Little penetration of innovation; low added value in the main economic vectors of the city. The administration and the Polytechnic University lead in part innovation projects- Lack of preferential marketing channels of priority agricultural products. Absence of innovation- Recycling of professionals in customer service in sectors affected by tourism |

Source: Own creation based on the Strategy for Sustainable and Integrated Urban Development of the Gandia Town Council and the report Territorial Diagnosis of La Safor (Sigalat et al., 2018a).

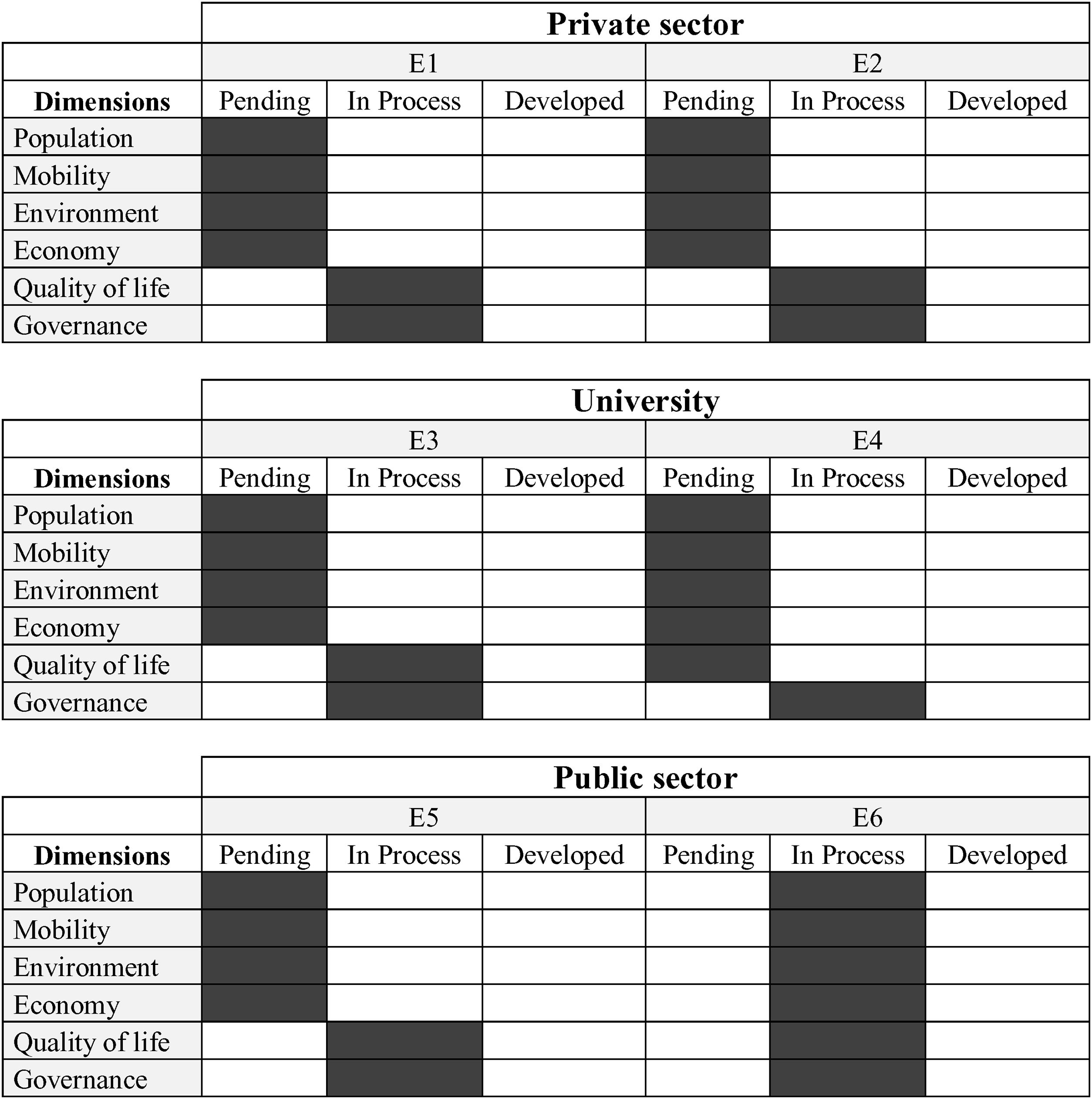

Based on the smart city dimensions and following the methodology explained, key tourism informants were consulted in order to contextualise the destination based on the requirements proposed by the model. By way of summary, the following table details the responses of the different informants consulted to each of the dimensions or basic pillars of smart cities based on the destination studied (Table 3).

One of the keys to ensuring the smart focus is achieved is the role represented by the city's population. As regards the population dimension, citizenship constitutes the main nucleus around which the rest of the city's dimensions and components must revolve. This approach necessarily requires the participation of stakeholders in their determination to solve real problems. Beyond the orientations of the technological companies involved in the destination with some incipient initiatives, it has not been possible to provide an essential and shared consensus attempting to incorporate the different interest groups in the debate on the public affairs of the destination in collectively defined objectives. Thus, the majority of the interviewees considered that this cornerstone of the smart paradigm still remains to be developed. This quote from one of the participants interviewed is highly illustrative: “First of all, technology needs to listen to people, to businesses… to see the problems first and… after that decide which is the best…” (E2). Smart cities are more about citizens than technologies for the resolution of real problems. Although, as noted by Tomàs and Cegarra (2016), the smart city has left little room for citizen participation, and both citizens and other interest groups have been left out of the smart model definition: “There is a lack of awareness in the population and stakeholder involvement in a global vision of the issue. The basic problems are not technological.” (E5). So, the model according to authors such as Hernández (2007) or Fernàndez (2014), among others, does not cover the real protagonists.

In turn, the mobility dimension refers to the sustainability, efficiency and safety of transport systems and infrastructures, as well as accessibility at local and other territorial levels. This is a dimension pending development. On this issue, territorial planning and acting with sustainability-based criteria have not been the norm: “The problems of the N-332 road and variants are a disaster due to traffic congestion and pollution issues for the city and the region.” (E5). Likewise, this is compounded by the deficit of public transport in the region with respect to the destination: “There is a considerable lack of territorial cohesion in terms of regional transport to the destination … The private vehicle has won the battle.” (E4). Consequently, the private vehicle becomes the main means of transport, causing serious problems in a destination that triples its population in the summer period. Decisions on transport infrastructure should therefore be subject to intelligent planning to articulate the destination, linking it with the municipalities of the region's interior as well as outwardly (Vercher & Sigalat, 2017).

The governance dimension (government) refers to the notion of transparency. In other words, the fact that the city manufactures and generates data through all kinds of open source technology for the entire smart city value chain, from Big Data4 to the Internet of Things (software, sensors, etc.) and other applications and that the resulting information is accessible, as set forth in the 1999 Aarhus Convention (Enerlis et al., 2012). Thus, most of the interviewees consider that this basic pillar of the smart paradigm is being developed. Therefore, this intelligence system able to effectively capture, analyse and interpret information in real time advocated by López de Ávila et al. (2015) for consideration as an STD, is in its primary phase. In this respect, the comment by one of the participants interviewed is highly illustrative: “Steps are being taken… but more by the Administration than the private sector… Adapting a smart model is largely going to be a very laborious process, as the sector is very traditional” (E1). However, the Administration has taken important steps with creation of the Gandia City Council Transparency Portal and other smart initiatives derived and guided by technological companies (and listed in the SWOT analysis).): “The city of Gandia is taking steps in all dimensions of the smart city initiative, especially in the Smart Government and Smart People dimensions, which I understand to be key dimensions for development of the others. In Smart Government, on the one hand I highlight the city's commitment to e-Administration and open government to achieve a better relationship with the citizens. The development of a Smart Tourism Master Plan, currently in the drafting process… and scheduled for presentation during the first four months of 2019… Contains several elements of the smart city plan, and it is intended to be a coherent tool for development of the Smart Destination project in Gandia” (E6).

Regarding the sustainability dimension, the city is developing interesting projects, especially in terms of beach dune conservation and the environmental preservation of landscapes, the accessibility of its beaches with recognised tourism quality seals, as well as an adequate hotel infrastructure adapted to tourists with special needs. The growing environmental sensitivity among public officials, businesses and citizens should be an opportunity for in-depth study to assess the numerous environmental resources (Sigalat et al., 2018a), as issues such as traffic congestion and noise and environmental pollution in a destination that triples its population both in summer and other holiday periods throughout the year are perceived by those consulted as factors still pending resolution: “Traffic, noise and parking… at the beach are problems we’ve always had and they need to be resolved.” (E2), “We must be more efficient also with lighting, becoming more energy efficient in many areas…” (E5). To the above information we shall add a consideration of interest that reminds us that rather than being a techno-intelligent model, the project must respond to the problems of citizens and businesses: “It's not just about making technological improvements or focusing only on our tourist offer… There is still a lot to be done on urbanism issues as well and technology alone is not going to resolve this.” (E4).

As for the economic dimensions, and following its theoretical approach, the smart city project represents a model that hones the competitive edge of territories, with a positive impact on the quality of life and encouraging the attraction of investments. When implementing a smart model, it is essential to be able to quantify the return on the investments made, both in economic and social terms (Enerlis et al., 2012). In other words, to be able to answer which costs, what income and what savings can be obtained by rolling out the smart model. In this sense, although there is a perception on the part of the actors involved that this model will sharpen the destination's competitive edge, with positive repercussions in all areas – “This smart city approach can help improve competitiveness thanks to the improvement in the quality of the tourist offer at the destination.” (E3) – it is no less true that it is still perceived by the interviewees as very distant and yet to be developed, both because it is seen as a costly issue – “The tourism sector here is very traditional in general … it's going to be expensive.” (E2), “The start-up technology is expensive and the sector needs to see the return on investment in the mid-term…” (E1) –, and not yet widely known: “There is no common vision or understanding of the sector in all this … In fact, all this smart city stuff is something that many of us, including business people, don’t even know what it is …” (E4).

Finally, regarding the quality of life dimension, the informants consulted note that it is a destination and an area with a diverse and high value natural heritage, located in a privileged geographical environment, with excellent weather conditions and an appreciable quality of life, which, along with the notable resources and services, both public and private, present in the city, mean that if we can manage to unify and optimise their management and focus the provision of services using these technologies, an even higher quality of life for citizens and visitors can be achieved: “Gandia is a privileged destination … if we know how to unite all this type of technologies and put them at the service of citizens and the tourism sector in the future, we will achieve that Smart Living, because the base is good.” (E5). So, the city has the basis for development of so-called Smart Living (quality of life of the destination). All that remains to be done consists of assembling the smart tourist information systems in the destination with the participation of interest groups and taking into account the rest of the dimensions in this transition to becoming a Smart Tourism Destination. However, according to Buhalis and Amaranggana (2014), this calls for the creation of a “tourist” governance that brings together public-private and community collaboration in this type of projects.

ConclusionsBased on analysis of the outcomes using the stated methodology, we conclude that Gandia can be considered a city that presents characteristic features of a smart tourist destination. However, to be considered a smart tourist destination, it should comply more broadly with all the dimensions or cornerstones proposed for the smart city. Although most of the interviewees considered the basis to be sound, the destination is still in the initial phase of adopting the pertinent technological strategies to align it with the requirements stipulated by the smart model. Likewise, the citizen dimension and its participation should be considered a key pillar of the model.

Cities, as the collective projects that they are (or should be), accommodate multiple collectives and groups, often with interest diverging from each other. The model must respond to these, as well as being useful to configure inclusive cities. The smart city should tend towards an inclusive innovation model (Alvarado, 2017). Participation in these processes, and with instruments that make it possible, still remains a pending assignment. Moreover, it is not an urban model focused on the technological-smart, but rather an interdisciplinary terrain. Dialogue, participation and a critical vision among the interest groups are required so that its design can provide opportunities for the destination and its inhabitants. But also for tourists and visitors, who should likewise participate with their opinions in more in-depth analyses of the destination regarding the issue.

Interesting future research lines could consist of carrying out a quantitative study counting on the perception of tourists and residents regarding how “smart” the destination is, in addition to the companies that provide tourist services, with the aim of expanding information and giving content to the dimensions set out in the smart paradigm. Likewise, the design of indicators that serve to evaluate the proposed objectives. So, today, the destination is in an initial phase of the model in its transition to becoming a Smart Tourism Destination. We hope that in the near future the model, given the opportunities that it entails, will be developed and enjoy the participation and intervention of smart citizens with the aim of providing a response to the doubtful question of whether this incipient urban-technological paradigm is advancing towards a reality or if it will turn out to be no more than a fad with the sole benefit of territorial marketing.

The authors thank the Tourist Intelligence Business Chair of the Universitat Politècnica de València and the Town Hall of Gandia, for its support in this research.

UIA-CIMES is a Work Programme of the International Union of Architects: “Intermediate cities and world urbanization”. The aim is to create a framework for reflection on intermediate cities in the face of the significant changes taking place in recent decades in world population settlement patterns. The initial document of CIMES work programme is available at Llop and Bellet (1999).

In this sense, in 2019 this city joined the Valencian Community Smart Destinations Network in order to access lines of subsidy and technical support for working with the smart tourism methodology being applied by the Valencian Community. The Valencian Institute of Tourism Technologies (Invat·tur), through the DTI CV Office, is the institution responsible for coordination of the Network. Please see link: http://invattur.gva.es/red-de-destinos-turisticos-inteligentes-comunitat-valenciana.