Advocacy for knowledge sharing (KS) is increasing as it can improve novelty and agility in policy development and service delivery. To determine the combination of factors that best contributes to high-quality government–citizen KS, this study adopts necessary condition analysis (NCA) and a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Three primary findings are supported. Cities with higher economic development achieve superior KS by enhancing citizens’ motivation to participate; traditional cities that are in transition succeed in KS by leveraging the established strength of the local government; in contrast, less developed cities succeed in KS based on central government guidance. These findings highlight the significance of comparing multi-factor configurations across scenarios. They can be utilised to discover suitable solutions for government–citizen KS in different cities.

Knowledge management is increasingly advocated as a means to enhance innovation and adaptability in policy formulation and service delivery. Consequently, civil servants and citizens engaged in public affairs have become knowledge workers (Park et al., 2015). Management is acknowledged as a significant source of innovation, which is essential for an organisation to develop a competitive advantage (Amabile & Pratt, 2016; Kim et al., 2021; Perotti et al., 2022). As a knowledge-centred activity, knowledge sharing (KS) is an important means for people to apply and innovate knowledge and ultimately gain a competitive advantage (Fischer & Döring, 2022; Pandey et al., 2018). By sharing knowledge among employees, within teams and between teams, organisations can capitalise on knowledge-based resources. Positive KS is positively correlated with absorption capacity, innovative capacity, team performance and value creation, according to research (Cassia et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021).

In public organisations, the escalating human capital crisis caused by layoffs, resignations and retirements necessitates more efficient knowledge-capture strategies (Pee & Kankanhalli, 2016). The potential benefits that can be realised through KS have garnered significant interest from public organisations in Europe and the United States. Governments invest a substantial amount of time and resources in KS across multiple levels and departments. As digital technology evolves, public organisations increasingly utilise information technology to strengthen their KS and knowledge application and creation capabilities (Lim & Ok, 2021; Müller, 2018; Pandey et al., 2021). This makes KS vital for public organisations.

However, empirical evidence on the impact of KS on performance is scant (Stier, 2015). KS is not always successful due to a variety of internal and external factors, and such failures can result in significant cost waste. Both researchers and practitioners concur that the success of KS depends on participants’ attentiveness to organisational and interpersonal contexts and individual traits (Pee & Kankanhalli, 2016). Consequently, many studies have focused on identifying KS's critical success factors (CSFs). For example, Liu et al. (2019) found that cultural differences can affect KS (Oyemomi et al., 2019), while Nguyen et al., and Gregory (2022) showed that opportunity and collectivism are essential in KS (Nguyen et al., 2022); Nguyen (2020) emphasised that, in addition to individual factors, social factors frequently influence KS. Similarly, Perotti et al. (2022) hypothesised that KS factors exist at the individual, organisational and social levels (Perotti et al., 2022). While the studies on CSFs of KS have evolved from single to multi-factor studies, the aforementioned research ignores the associations between factors. Although KS is affected by various factors, the significance of these elements in ensuring the success of KS, and the effect of combining different elements, remain undetermined. Similarly, the recipe is more significant than the ingredients in a dish (Ordanini et al., 2014). Consequently, this study poses the following research question:

Which combinations of KS's influencing factors result in positive KS? This research topic can be broken down into three sub-questions:

Q1: What factors influence KS?

Q2: Are these factors sufficient and necessary?

Q3: What combination of these factors produces higher government–citizen KS?

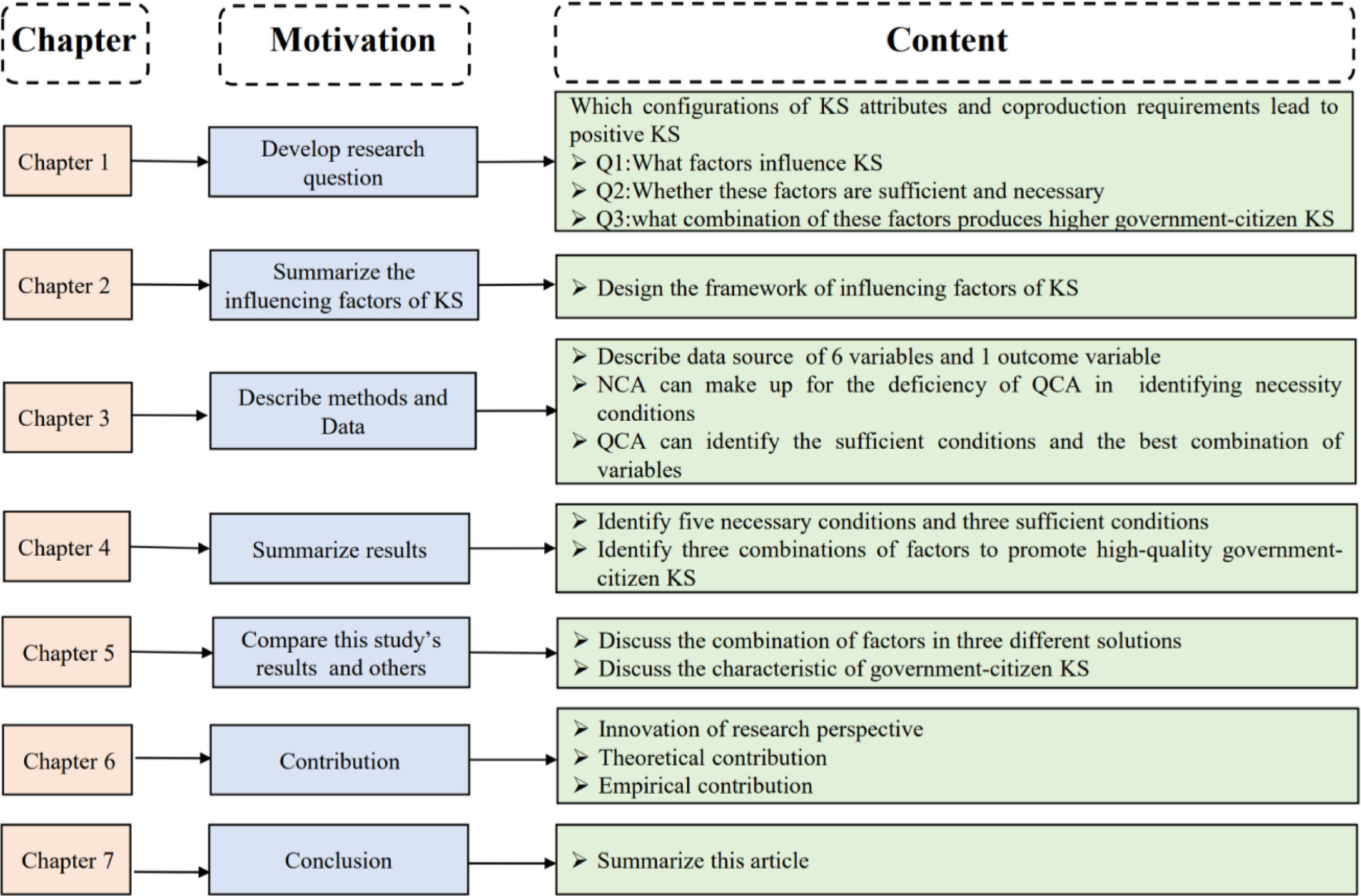

Fig. 1 illustrates the motivations and content of the chapters in this article, and the major study topic is discussed and divided into three sub-questions. Chapter 2 outlines the literature research and constructs the framework of KS's influencing factors, which is utilised to answer Question 1. Methodology, data and outcomes are demonstrated in Chapters 3 and 4. This section discusses Questions 2 and 3. NCA is used to assist qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in determining necessary conditions, whereas QCA are used to identify adequate conditions and optimum combinations. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 are the discussion, contribution and conclusion respectively.

Literature reviewKS is a process of transferring knowledge and generating new knowledge by interacting with others or by discussing the knowledge known to the individual with the knowledge transfer. This can make knowledge available to other members of the organisation (Akram et al., 2017; Balle et al., 2019; Yap & Ng, 2018). KS can build an organisation's trust (Willem & Buelens, 2007), creativity (Ahmad & Karim, 2019), environmental and economic sustainability (Leith & Yerbury, 2019), job satisfaction (Rafique & Mahmood, 2018) and affective commitment (Hendryadi, Suratna, Suryani & Purwanto, 2019). Ultimately, KS promotes organisational performance (Ahmad & Karim, 2019; Vong et al., 2016) and provides organisations with a competitive edge. Therefore, KS has been used in various fields. In the medical field, the role of the patient in KS (Joseph-Williams et al., 2014) can promote medical decision-making qualities (Lin & Chang, 2008). There is also a growing research trend in tourism (Yiu & Law, 2014), such as key variables, relationships and implications for tourism organisations (Yiu & Law, 2014). Furthermore, increasingly, international travellers have influenced how hotels manage their customer satisfaction reviews and ratings (Nguyen & Malik, 2022b). In addition, scholars are also concerned about KS in the field related to the network such as virtual communities (Fang & Chiu, 2010; Lin et al., 2009), global software development (Zahedi et al., 2016) and online KS in organisations (Nguyen, 2021). In addition, KS in business organisations (Lin et al., 2009) and in higher education institutes have attracted substantial attention. Furthermore, KS in government has attracted scholars’ attention (Willem & Buelens, 2007), such as E-Government in the KS.

Based on the importance of KS, scholars have begun to focus on how to realise KS of high quality. In this process, the influencing factors of KS have received universal attention. Various organisational, social and individual factors can affect KS. Scholars have investigated the factors of KS at different levels, including the individual (Nguyen et al., 2022), organisational (Akram et al., 2020), technological (Fischer & Döring, 2022; J. Pandey et al., 2021) and social levels (Halisah et al., 2020). Previous studies have highlighted the factors affecting KS. However, the majority of previous studies focus on one factor or a group of factors on KS but do not comprehensively explore the factors affecting KS. One factor or a group of factors cannot achieve success in KS. Therefore, to construct a framework of KS factors, this study provides an overview of the distinct factors at the various levels that affect KS. The results show that the influencing factors of current KS involve four levels.

The premise of KS: Participants’ motivationIntrinsic motivation is positively related to KS tendencies (Sun et al., 2022). ‘Motivation refers to processes that instigate and sustain goal-directed activities’ (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020).

In the process of KS, participants’ intrinsic motivation can guide the action of KS (Sun et al., 2022), and KS is an entirely self-motivated behaviour (Bavik et al., 2018); Participants’ motivation is expected to represent self-imposed intentions and demands within their work environments, and to determine the direction, intensity and duration of an individual's work (Van Iddekinge et al., 2018), such as cognitive job demands and job autonomy (Gagné et al., 2019); this influences how they want to act and helps them choose what they want to do to achieve their goals. These participants’ motivation concludes economic, relational and learning motives (J. Chen et al., 2022). In addition, motivation of KS also can be stimulated by rewards, practical benefits and psychological rewards (Gooderham et al., 2022). Role of individuals in organisations are proposed having effect on KS (Nguyen & Malik, 2022a).

Therefore, if participants are poorly motivated, have little motivation to partake in co-creation processes (de Jong et al., 2019) or do not trust other participants (Treves et al., 2017), KS will be infrequent (Lam & Lambermont-Ford, 2010). One element of KS is a phenomenon called the Bystander Effect, in which some people hold the opinion that other participants will contribute to common interests. Certain studies have focused on regulating these self-organising participants (Visser et al., 2021); public communication was proposed to remedy citizens’ distrust in government (Alon-Barkat, 2020). Therefore, KS in an organisation will be promoted if the economic, learning or status motivations of the participants are satisfied.

Condition of KS: Participants’ capacityParticipants’ capacity in KS is another key factor (Li et al., 2022). Based on this article, the participants in government–citizen KS can be described as governments and citizens. In the process of KS, the government and citizens have more extensive and profound knowledge, which is more conducive to the behaviour of KS (Carnahan, Agarwal & Campbell, 2010). Inversely, the knowledge-sharing sender in KS has always been troubled by perceptual knowledge; a recipient's lack of absorptive capacity and causal ambiguity can also result in low-quality KS. For example, patients’ limited capacity to express sometimes cannot improve medical decision-making quality; therefore, KS cannot be completed (Joseph-Williams et al., 2014).Through research on KS's capacity of faculty and students in a higher education institute, Jeng & He found that they chose not to share data because they were unaware of the benefits and methods of doing so (Jeng & He, 2022).

Capacity can be divided into professional skills related to knowledge and non-professional skills (Li et al., 2022). Professional skills refer to specialised knowledge of a particular industry or field in KS scenarios, such as strategic HRM and emotional intelligence in organisations (Mura et al., 2021). However, non-professional skills refer to management-related knowledge, such as leadership (El-Sabaa, 2001; Huang et al., 2008), communication (Carnahan, Agarwal & Campbell, 2010) and managerial skills (Carnahan, Agarwal et al., 2010). In KS, participants’ non-professional skills often receive more attention.

The support of KS: RelationshipThe relationships involved in the organisation also significantly impact KS. The intersection of diverse participants’ relationships may result in various knowledge icebergs (Yu et al., 2022). It has also been found that trust-based relationships and interactions are typically more strongly related to greater KS (Srirama et al., 2020), and trust also played a significant role in KS (Rodríguez-Aceves et al., 2022). In addition, integrity-based trust and affective commitment, which underlie cultural homophily, are encouraged in group relationships to reinforce relational embeddedness and achieve high-quality KS (Chumg et al., 2022). Certain scholars have classified relationships in detail and concluded that KS is influenced by experiences in sustained relationships, coupled with an awareness of knowledge sources and expectations of reciprocity in relationships (Obembe, 2013).

In addition, this relationship is sometimes described as organisational culture (Petrakis et al., 2017), and justice (Akram et al., 2020) and organisational justice on KS are often mentioned (Akram et al., 2017). Prior research has demonstrated that relationships are critical for knowledge creation and transfer. Relationships can be embodied in concrete forms, such as the extent of sharing a similar knowledge-sharing base, the degree of interaction between receivers and senders in KS and a mutual understanding of knowledge sources. Rewards, recognition, promotion, organisational relationship factors and organisational support are positively significantly related to KS.

The tool of KS: TechnologyDigital technology can create more efficient KS (Deng et al., 2022) and provide new pathways for participants to develop and sustain their habits through the use of technology (Chumg et al., 2022). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) are established as drivers of this new wave of change in the redefinition of the relationship between the two parties (Gagliardi et al., 2017). In recent years, governments have often used ICTs, social media in particular, to communicate with citizens (Falco et al., 2018); this significantly reduces the social and political gaps between governments and citizens, while also increasing trust (Starke et al., 2020). Researchers have also assessed the role of social media in knowledge sharing and concluded that most social media study focuses on SM for KS user behaviour, utility and benefits, social media platforms and tools (Ahmed et al., 2019).

This study develops and tests a theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model, which explains the perceived usefulness and usage intentions in social influence and cognitive instrumental processes; these technologies are playing increasingly significant roles (Christensen, 2019; Correa et al., 2019). Online services (Orzech et al., 2018) and digital public services are developed to support smart city development (Pereira et al., 2018; Thynne & Wettenhall, 2004). However, this also creates various challenges (Dobrolyubova, 2021; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2019), such as a lack of digital governance (Nysveen et al., 2005) and institutional ethics, among others (Kaisara & Pather, 2011; Lee-Geiller & Lee, 2019).

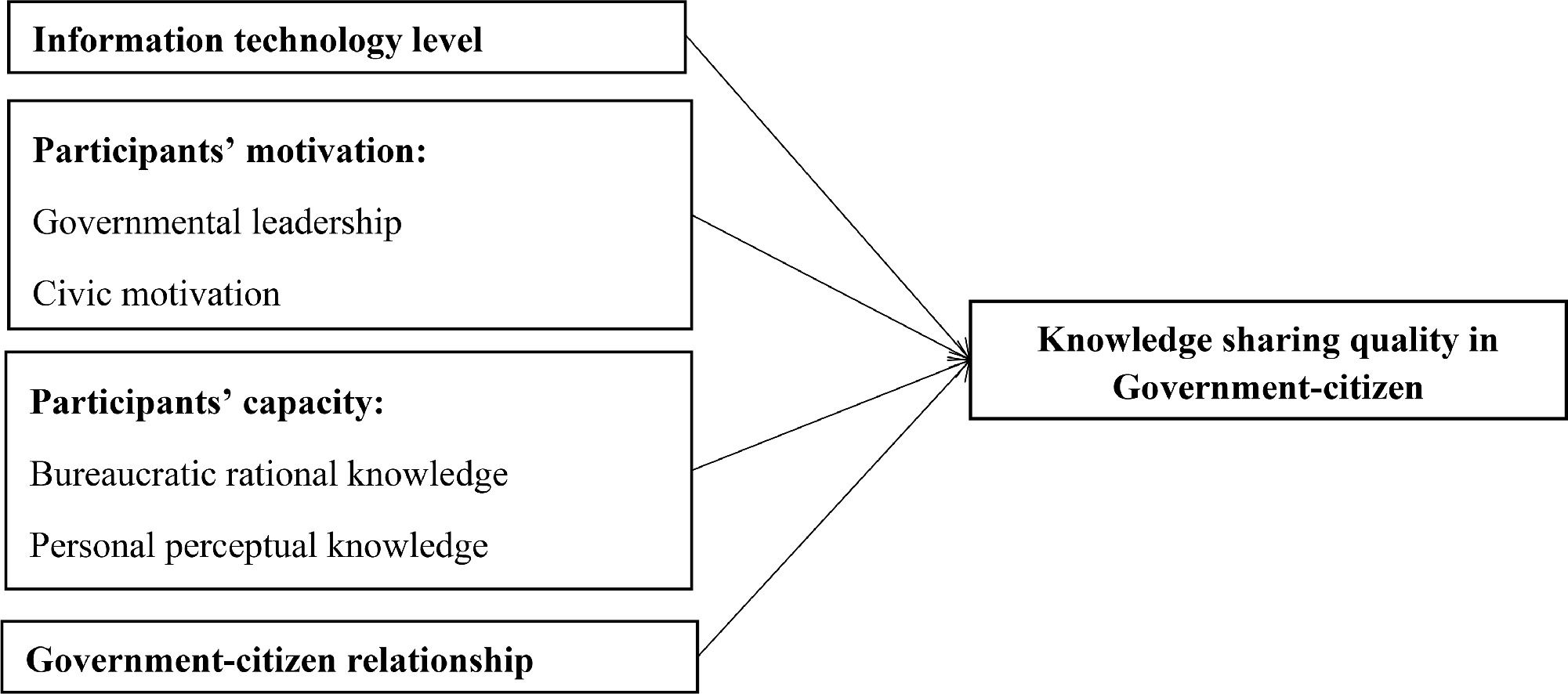

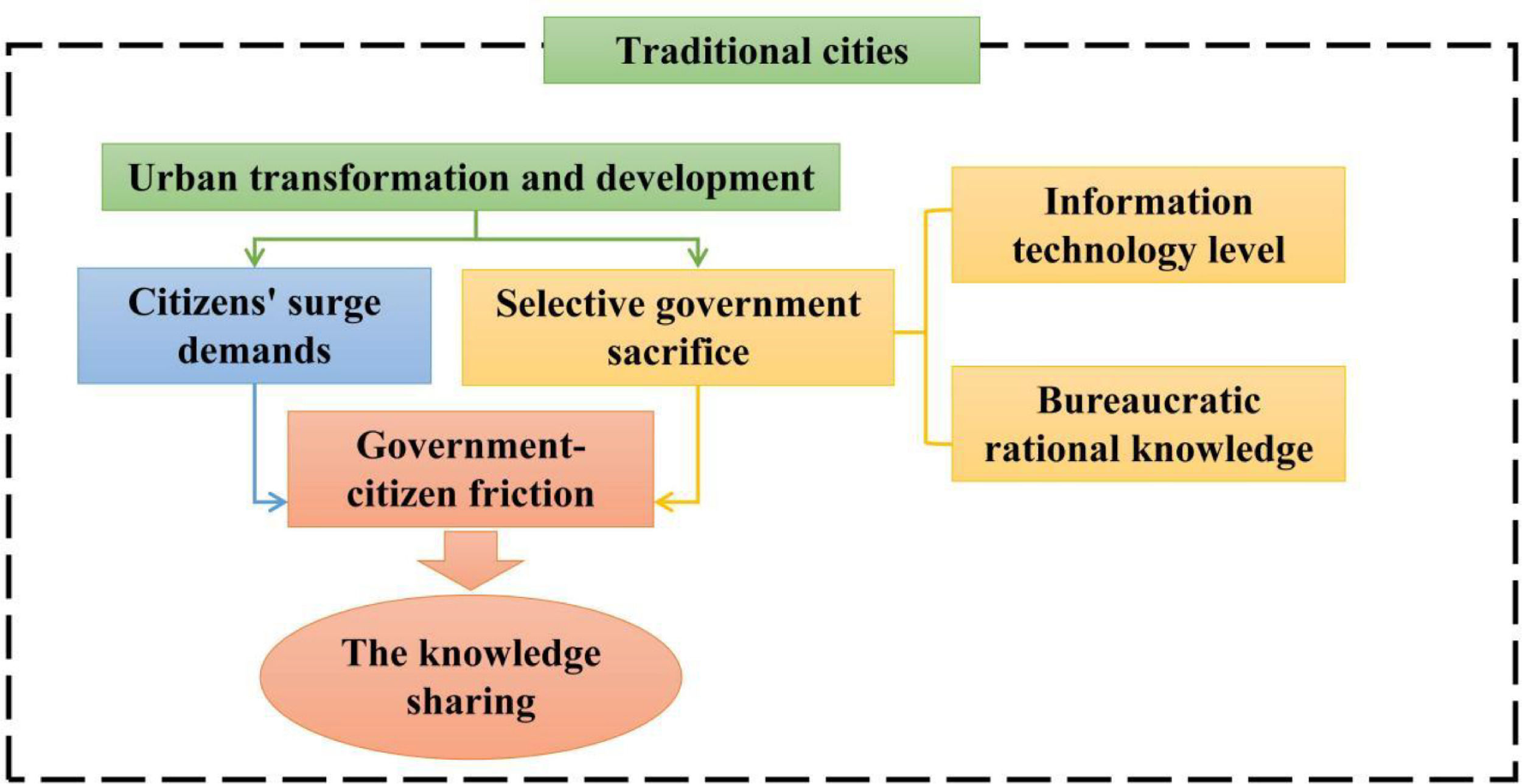

Analytical frameworkThis study's framework is shown in Fig. 2. It configures participants’ motivation in conjunction with their capacity to construct a theoretical model. First, participants’ motivation includes governmental leadership and civic motivation. Second, participants’ capacity includes bureaucratic rational knowledge and personal perceptual knowledge, which can demonstrate the ability to exchange knowledge. Finally, since the appropriate KS depends on the interactive context's characteristics, this study introduced two variables: ‘information technology level’ and ‘government–citizen relationship’. Based on the KS theory, six variables are identified as influencing factors of KS, including information technology level, government–citizen relationship, governmental leadership, civic motivation, bureaucratic rational knowledge and personal perceptual knowledge.

Methods and dataMethodsThe purpose of this study is to examine the interaction of the combination of government–citizen interaction factors for achieving high-quality KS between governments and citizens and whether these factors are sufficient and necessary. Therefore, a QCA and a necessary condition analysis (NCA) were conducted.

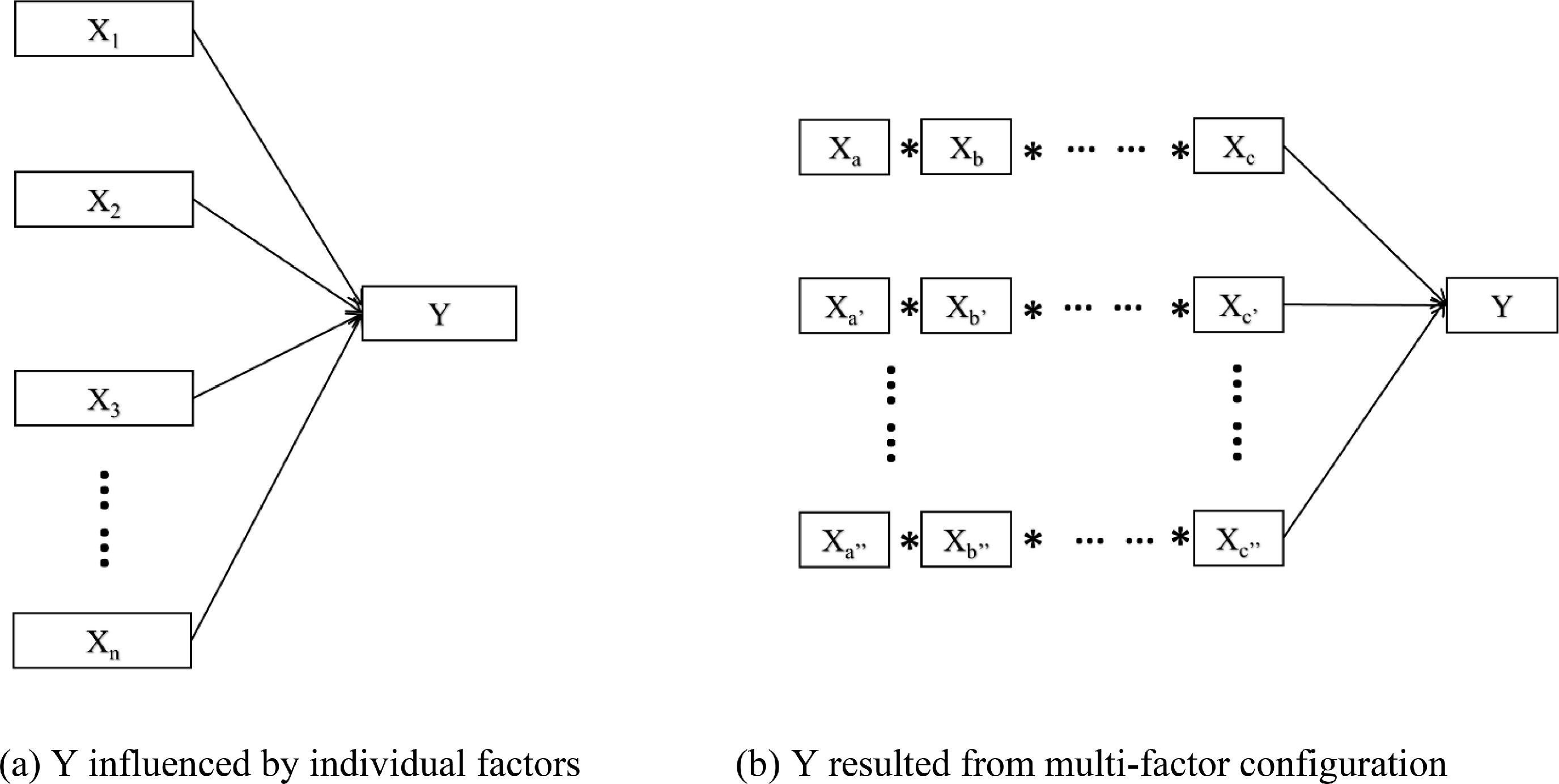

QCA can analyse the complex causal relationship between conditional configurations and results from small and medium sample sizes (Rihoux, 2006), and it combines the advantages of both qualitative and quantitative analyses. As shown in Fig. 3, (a) represents the relationship between a single X and Y, which most previous research methods explore; (b) indicates that the QCA method can identify the occurrence of Y in combination with multiple factors. QCA responds to the doubt of the ‘extensibility’ of qualitative analysis of a few cases and to some extent, makes up for the deficiency of extensive sample analysis in qualitative change and phenomenon analysis. However, QCA differs from the traditional approach to quantitative analysis, which focuses on combining factors. Instead, QCA can avoid errors caused by selecting control variables in quantitative research. QCA uses Boolean algebra to avoid missing variable bias; hence, there is no requirement for control variables in the QCA method (Fainshmidt et al., 2020; Skaaning, 2011). Consequently, the method of fsQCA is an excellent fit for identifying the combination and sufficient condition.

However, fsQCA has limitations in identifying necessary factors. It identifies whether a factor is adequate for a result of configuration but cannot accurately identify whether this factor is necessary. Although both fsQCA and NCA can be used to analyse the necessary conditions, fsQCA restricts them to an extremely narrow scale through the theoretical scope (Torres & Godinho, 2021). Typically, FsQCA finds considerably fewer necessary conditions in data sets than NCA (Dul, 2016b). Moreover, NCA can make up for the deficiency of QCA and allow the estimation of ‘the necessity effect size of a condition X for an outcome Y’. Therefore, the NCA can identify the factors that, when satisfied, do not necessarily catalyse results; however, their absence certainly does not produce results. Consequently, the combination of NCA and fsQCA is more valuable for the exploration of result factors (Vis & Dul, 2018). FsQCA and NCA can provide two different and complementary perspectives over the necessary conditions to achieve an outcome; therefore, it is useful to use both together to reach more robust conclusions (Torres & Godinho, 2021).

Data sourceGovernment websites were used as the data source in this study, since they are comprehensive platforms that show government–citizen information exchange (Srirama et al., 2020). This study selected all cities’ government official websites in China as samples, yielding a total of 293 official websites.

Variables(I) Information technology level. This study uses three indicators to measure the information technology level of government websites. In this study, three conditions were listed: 1. The homepage of the website and each column are updated at any time. 2. The website provided fuzzy search and keyword aggregation functions. 3. The website was created with an intelligent answering robot, which could realise real-time question answering. These conditions were used to measure if all conditions were met (record 1 if 0.67 for two conditions and 0.33 for one condition and record 0 if the condition was not met).

(II) Governmental leadership. This study took the frequency and level of guidance documents on government–citizens interaction from government websites. Subsequently, five experts were invited to evaluate them according to the government's leadership. Based on the score, the findings were divided into four grades: 1, 0.67, 0.33 and 0.

(III) Civic motivation. We took the frequency of browses, downloads and comments on government releases to describe civic motivation. This was also divided into four grades: 1, 0.67, 0.33 and 0.

(IV) Bureaucratic rational knowledge. This study uses three indicators for bureaucratic rational knowledge. 1. Documents could be displayed in digitisation, diagrams, audio and video and animation, etc. 2. Easily queried and obtained various development government data. 3. Timely released, updated and maintained epidemic prevention and control topics. These conditions were used to measure if all conditions were met (record 1 if 0.67 for two conditions and 0.33 for one condition, and record 0 if no condition was met).

(V) Personal perceptual knowledge. This study used the logic, emotion and degree of truth of the comments from the government website to describe personal perceptual knowledge. Five experts anonymously evaluated this indicator. Similarly, individual rational knowledge was divided into four grades: 1, 0.67, 0.33 and 0.

(VI) Government–citizen relationship. Citizens’ satisfaction with the government published on websites was used to measure the relationship between government and people. Take Zhejiang as an example1. The relationship between the government and the public was divided into four relationships, which were recorded as 1, 0.67, 0.33 and 0.

Outcome Variable. In government–citizen KS, the outcome variable was whether KS was effectively produced. This study used three indicators to measure it as follows: 1. The transparency and openness of consultation, investigation and interview processes; 2. Whether the response is evasive or perfunctory; and 3. Whether the government's response rate is over 90% (record 1 if 0.67 for two conditions and 0.33 for one condition; record 0 if no condition was met).

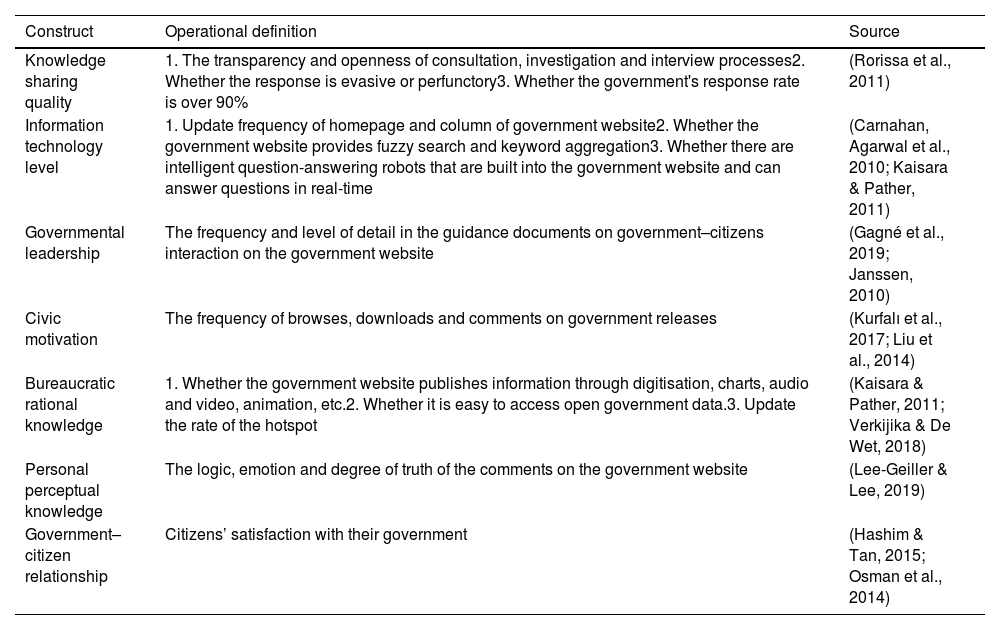

Therefore, these six indicators were considered conditional variables to realise KS between the government and citizens. Subsequently, the original data were transformed according to the variable assignment criteria to obtain the membership results of each variable in the case, which were finally imported into fsQCA3.0 software for a fuzzy-set analysis (See Table 1).

Construct and operational definition.

| Construct | Operational definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge sharing quality | 1. The transparency and openness of consultation, investigation and interview processes2. Whether the response is evasive or perfunctory3. Whether the government's response rate is over 90% | (Rorissa et al., 2011) |

| Information technology level | 1. Update frequency of homepage and column of government website2. Whether the government website provides fuzzy search and keyword aggregation3. Whether there are intelligent question-answering robots that are built into the government website and can answer questions in real-time | (Carnahan, Agarwal et al., 2010; Kaisara & Pather, 2011) |

| Governmental leadership | The frequency and level of detail in the guidance documents on government–citizens interaction on the government website | (Gagné et al., 2019; Janssen, 2010) |

| Civic motivation | The frequency of browses, downloads and comments on government releases | (Kurfalı et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2014) |

| Bureaucratic rational knowledge | 1. Whether the government website publishes information through digitisation, charts, audio and video, animation, etc.2. Whether it is easy to access open government data.3. Update the rate of the hotspot | (Kaisara & Pather, 2011; Verkijika & De Wet, 2018) |

| Personal perceptual knowledge | The logic, emotion and degree of truth of the comments on the government website | (Lee-Geiller & Lee, 2019) |

| Government–citizen relationship | Citizens’ satisfaction with their government | (Hashim & Tan, 2015; Osman et al., 2014) |

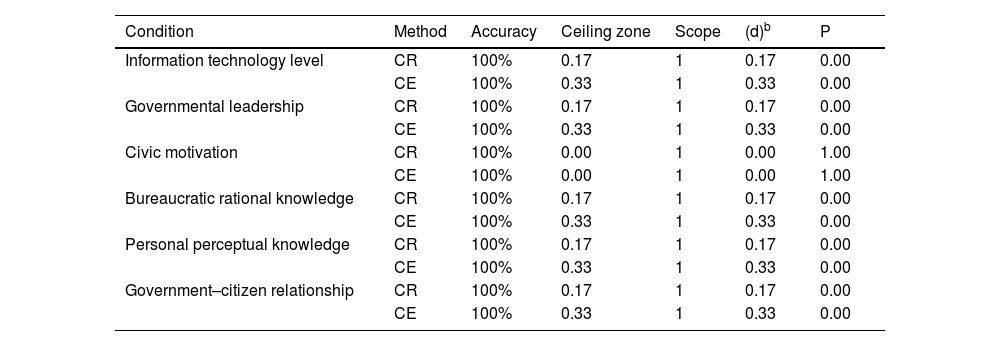

NCA can identify whether a variable is necessary for a specific result. The effect size is the bottleneck in NCA, representing the lowest level necessary to produce a specific result. The effect size value is between 0 and 1; the more significant the effect size is, the larger the effect value (Dul, 2016b).

The NCA method can handle both continuous and discrete variables. If X and Y have five or more levels, a ceiling function is generated using a ceiling regression (CR). Furthermore, if X and Y are dichotomous variables or discrete variables that are below level 5, the function is generated using an upper bound envelopment analysis (CE). Once the corresponding function is generated, the effect size can be analysed accordingly. NCA draws a ceiling line on the top of the data in an XY scatter plot; moreover, the empty space in the upper left corner suggests that high values of Y are not possible with low values of X (Dul et al., 2020). The area above this ceiling zone is a measure of the constraining effect of the identified necessary condition. The proportion of the potential area with observations that lies above the ceiling line is termed the effect size, d where C is the size of the ceiling zone and S is the size of the potential area with observations, termed the scope (Dul, 2016a). The computational formulas of d are simplified as follows.

Table 2 reports the results of the NCA analysis, including the effect sizes obtained by using CR and CE. In NCA, two conditions must be met: a) The effect size (D) is no less than 0.1 (Dul, 2016b); b) Monte Carlo simulations of permutation tests show that the effect size is significant (Dul, 2016b). In summary, ‘Information technology level’, ‘Governmental leadership’, ‘Bureaucratic rational knowledge’, ‘Personal perceptual knowledge’ and ‘Government–citizen relationship’ are significant, and the effect size is not below 0.1. Therefore, they can be considered necessary conditions for KS (Dul, 2016b). ‘Civic motivation’ (p = 1.0) test results are not significant, indicating that it is not a necessary condition for KS.

Analysis of results of necessary conditions of NCA method.

| Condition | Method | Accuracy | Ceiling zone | Scope | (d)b | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information technology level | CR | 100% | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.00 | |

| Governmental leadership | CR | 100% | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.00 | |

| Civic motivation | CR | 100% | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Bureaucratic rational knowledge | CR | 100% | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.00 | |

| Personal perceptual knowledge | CR | 100% | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.00 | |

| Government–citizen relationship | CR | 100% | 0.17 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| CE | 100% | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

Note: a. Membership value of fuzzy set after calibration. b.0 < d < 0.1: ‘small effect’; 0.1 ≤ d < 0.3: ‘medium effect’; 0.3 ≤ d < 0.5: ‘large effect’; 0 .5 ≤ d < 1: ‘very large effect’. Substitution test in NCA analysis (permutation test, number of redraws =10000)

The bottleneck analysis results are reported in Table 3. The bottleneck level (%) refers to the level value (%) that must be satisfied within the maximum observation range of the antecedent condition to reach a certain level in the maximum observation range of the result (Dul, 2016b). As shown in Table 3, to achieve 70% ‘Knowledge sharing quality’, cities must reach a certain level with 9.1% of ‘Information technology level’, ‘Governmental leadership’, ‘Bureaucratic rational knowledge’, ‘Personal perceptual knowledge’ and ‘Government–citizen relationship’, while ‘Civic motivation’ has no bottleneck. Therefore, when the quality of KS is low (60% or below), none of the six factors of government–citizen interaction are necessary. With the improvement of ‘Knowledge sharing quality’, the requirements for the six factors will also increase. Finally, to reach 90% ‘Knowledge sharing quality’, 69.7% of all factors except ‘Civic motivation’ are needed. Therefore, the bottleneck analysis results further prove the extent to which conditional variables are necessary.

Analysis results of NCA method bottleneck level (100%).

| y | Knowledge sharing qualityInformation technology level | Governmental leadershipCivic motivation | Bureaucratic rational knowledgePersonal perceptual knowledge | Government–citizen relationshipKnowledge sharing quality | Information technology levelGovernmental leadership | Civic motivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN |

| 70 | 9.1 | 9.1 | NN | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| 80 | 39.4 | 39.4 | NN | 39.4 | 39.4 | 39.4 |

| 90 | 69.7 | 69.7 | NN | 69.7 | 69.7 | 69.7 |

| 100 | NA | NA | NN | NA | NA | NA |

Note: A. CR method, NN = unnecessary.

The results of NCA show that having five conditional variables as necessary conditions has important effects on the dependent variables and the findings illustrate to what extent. This proves that the conditional variables selected in this study are valuable. However, it can also provide a reference for fsQCA.

QCA: Sufficient and configuration analysis of variablesThe indexes for measuring QCA results are consistency and coverage, as proposed by Ragin (Ragin & Strand, 2008). Consistency refers to how a condition variable is associated with an outcome variable, and coverage refers to the degree to which the condition combination explains the outcome. The computational formulas of consistency and coverage are simplified as follows (Davidavičiene et al., 2020):

When the fuzzy-set value of X is smaller than or equal to that of Y, and the consistency index is more significant than 0.8 (Pudi & Sridharan, 2012), X is considered a sufficient Y condition. Meanwhile, supposing that the consistency index is more significant than 0.9, X will be considered a necessary condition of Y. After a judgement on whether something is a sufficient or necessary condition, the degree to which the condition (or combination) X explains result Y may be further judged using the coverage index. Fig. 1 was analysed using fsQCA3.0. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 4, and the necessity analysis result of each condition is listed in Table 5.

Necessary condition analysis (Outcome variable: Knowledge sharing quality).

| Conditions tested | Consistency | Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Information technology level | 0.8819 | 0.7580 |

| ∼Information technology level | 0.3237 | 0.5524 |

| Governmental leadership | 0.8476 | 0.6851 |

| ∼Governmental leadership | 0.2216 | 0.4325 |

| Civic motivation | 0.7508 | 0.7329 |

| ∼Civic motivation | 0.2611 | 0.3601 |

| Bureaucratic rational knowledge | 0.8959 | 0.7190 |

| ∼Bureaucratic rational knowledge | 0.2346 | 0.4660 |

| Personal perceptual knowledge | 0.5552 | 0.6548 |

| ∼Personal perceptual knowledge | 0.5378 | 0.5964 |

| Government–citizen relationship | 0.5281 | 0.7316 |

| ∼Government–citizen relationship | 0.5549 | 0.5400 |

The results suggest that the consistency of indexes was below 0.9, indicating that not a single index is a necessary condition of government–citizen KS (Ragin, 2008; Skaaning, 2011). Therefore, a single KS factor is insufficient to constitute a necessary condition of sustainability for government–citizen KS. The consistency of the variables, ‘Information technology level’, ‘Governmental leadership’ and ‘Bureaucratic rational knowledge’ are more significant than 0.8, but smaller than 0.9, indicating that three variables demonstrated reliable explanatory power for the result of KS and could be considered as sufficient conditions. The results of NCA and QCA differ because they use different logic to identify necessary variables (Torres & Godinho, 2021). Consistency and coverage of other condition variables were not lower, suggesting they had specific explanatory solid power for the result. Since government–citizen sharing results come from ‘multiple complex concurrent causalities’, further analysis on a combination of condition variables is required to acquire more information.

Table 6 analyses how condition variables combine to result in an outcome variable. The frequency and consistency threshold values should first be set for the case. Based on the preceding and the samples of cases, the frequency and consistency threshold values were set to 1 and 0.8, respectively. The conditions that appear in both the intermediate and reduced solution are the core conditions of the solution. The conditions that appear only in the intermediate solution are the peripheral conditions. The intermediate solution was included in the meaningful ‘logic residue’. Therefore, the intermediate solution was taken for analysis.

Four configurations leading to succession performance government–citizen knowledge sharing.

| Configuration condition | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information technology level | ||||

| Governmental leadership | ||||

| Civic motivation | ||||

| Bureaucratic rational knowledge | ||||

| Personal perceptual knowledge | ||||

| Government–citizen relationship | ||||

| Consistency | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| Raw Coverage | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Solution Consistency | 0.93 | |||

| Solution Coverage | 0.84 | |||

Note: The black circles indicate the presence of a condition, and circles with an ‘ × ’ indicate its absence. Large circles indicate core conditions, and small ones indicate peripheral conditions. Blank spaces indicate ‘do not care’.

Table 6 displays the configurations of conditions leading to high-quality government–citizen KS. The overall solution consistency is 0.93, which is higher than the 0.75 level that Ragin suggested as being acceptable (Ragin & Strand, 2008). Coverage, which assesses the relevance of the necessary condition, is 0.84, meaning that the combined models account for approximately 84% of the membership in the outcome. Measures of consistency and coverage for each configuration are also reported in Table 6. Salient findings suggest that mature cities achieve superior governance performance by enhancing the willingness of the masses to participate. In contrast, young cities in KS succeed from government guidance or technological development.

Furthermore, among the four solutions, Solutions 1, 2 and 3 explained 80% of the selected cases, whereas the fourth explained below 1%. Therefore, Solution 4 will not be explained. The results are as follows:

- Ø

Configuration 1: Information technology level*Governmental leadership*Bureaucratic rational knowledge*Personal perceptual knowledge*Government–citizen relationship

- Ø

Configuration 2: Information technology level*Civic motivation*Bureaucratic rational knowledge*∼Personal perceptual knowledge*∼Government–citizen relationship

- Ø

Configuration 3: ∼Information technology level*Governmental leadership*Civic motivation*∼Bureaucratic rational knowledge*∼Personal perceptual knowledge*∼Government–citizen relationship

Solution 1: The harmonious governance path with Citizen Quality as the core

Solution 1 implies that citizens’ knowledge and the government–citizen relationship are the core factors, while information technology and the government leadership level are auxiliaries. As shown in Table 6, the coverage rate of Solution 1 is close to 0.5, explaining half of the samples in this study, indicating that this path applies to most cities and is a relatively common solution. These samples include cities in the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas, Beijing–Tianjin region, Provincial capital cities and certain cities with better economic development (e.g. Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Chengdu and Xian).

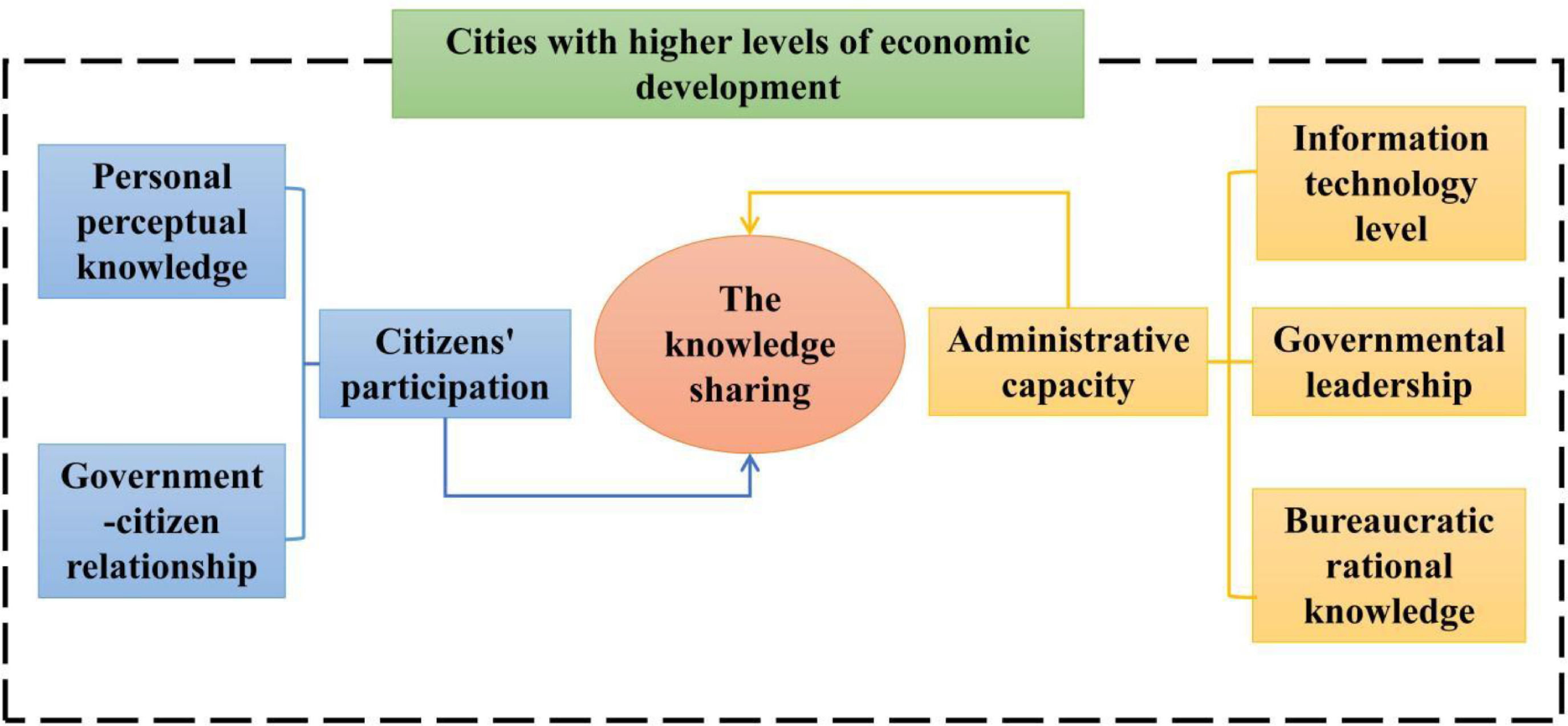

Fig. 4 describes how these cities have achieved KS. Factors related to the government and citizens are shown in yellow and blue, respectively; furthermore, green and red represents the objective environment and outcome, respectively. The success of KS in these cities derives from the efforts of both governments and citizens. Specifically, the government improves the administrative level based on ‘Information technology level’, ‘Governmental leadership’ and ‘Bureaucratic rational knowledge’ to improve the administrative level and collect citizens’ knowledge more effectively. Moreover, highly qualified citizens have the motivation to politically participate and the ability to transform ‘personal perceptual knowledge’ into government knowledge. Both the government and citizens are willing and able to share knowledge, so the successful government–citizen KS is realised. Solution 1 presents a harmonious and interactive co-governance ecology and shows that communication and cooperation between governments and citizens are valued.

Solution 2: The technical transformation path with Civic Motivation as the core

Solution 2 implies that high civic motivation, the absence of personal perceptual knowledge and poor government–citizen relationships can also promote high-quality KS. This solution had a coverage rate of 0.3 and explained a third of the samples. These samples predominantly included cities that rely on the advantages of resources and have achieved development before but have fallen behind and require transformation; Daqing is one such city. Although it was once known as the ‘City of Oil’, the city's development is now limited and urgently requires transformation due to the depletion of oil resources. Other such cities include Jilin, Dalian, Zhengzhou, Changsha, Wuwei and Ankang.

Fig. 5 depicts the second government–citizen KS solution. In these samples, cities of transition and development have impacted established stakeholders, resulting in a high propensity among residents to express discontent with the government, thereby reflecting the ‘citizen's surge demands. To restructure urban development, the government will choose a coercive governance strategy and selectively sacrifice some citizen interests, despite the fact that it has benefited from the development of the previous era regarding ‘information technology level’ and ‘bureaucratic rational knowledge’. For example, if a city wants to complete the shift from high-polluting heavy industry to low-polluting high-tech, it must close heavy industry enterprises, which is certain to provoke opposition from heavy industry practitioners, hence causing ‘government–citizen friction’. These disagreements do not directly lead to government–citizen KS. This mechanism ensures that, when expressing their dissatisfaction, those with minimal complaints garner the attention of the entire community, and the majority of citizens learn about the government's efforts for urban development, resulting in a knowledge exchange between the two parties. Therefore, KS is effective.

Solution 3: The government support path with Civic Motivation as the core

Solution 3 only explains a tiny sample of small and medium-sized cities, such as Suihua, Hegang and Chaoyang, with a coverage rate of 0.04. ‘Civic motivation’ is the primary component for both Solutions 2 and 3. The cities included in Solutions 2 and 3 are undergoing significant urban transition; however, each path has its own unique characteristics, as determined by the study's examination of sample cities. The technical transformation and government support paths with ‘Civic Motivation’ at its core can be summarised as ‘The technical transformation path with Civic Motivation at its core’ and ‘The government support path with Civic Motivation at its core’, respectively.

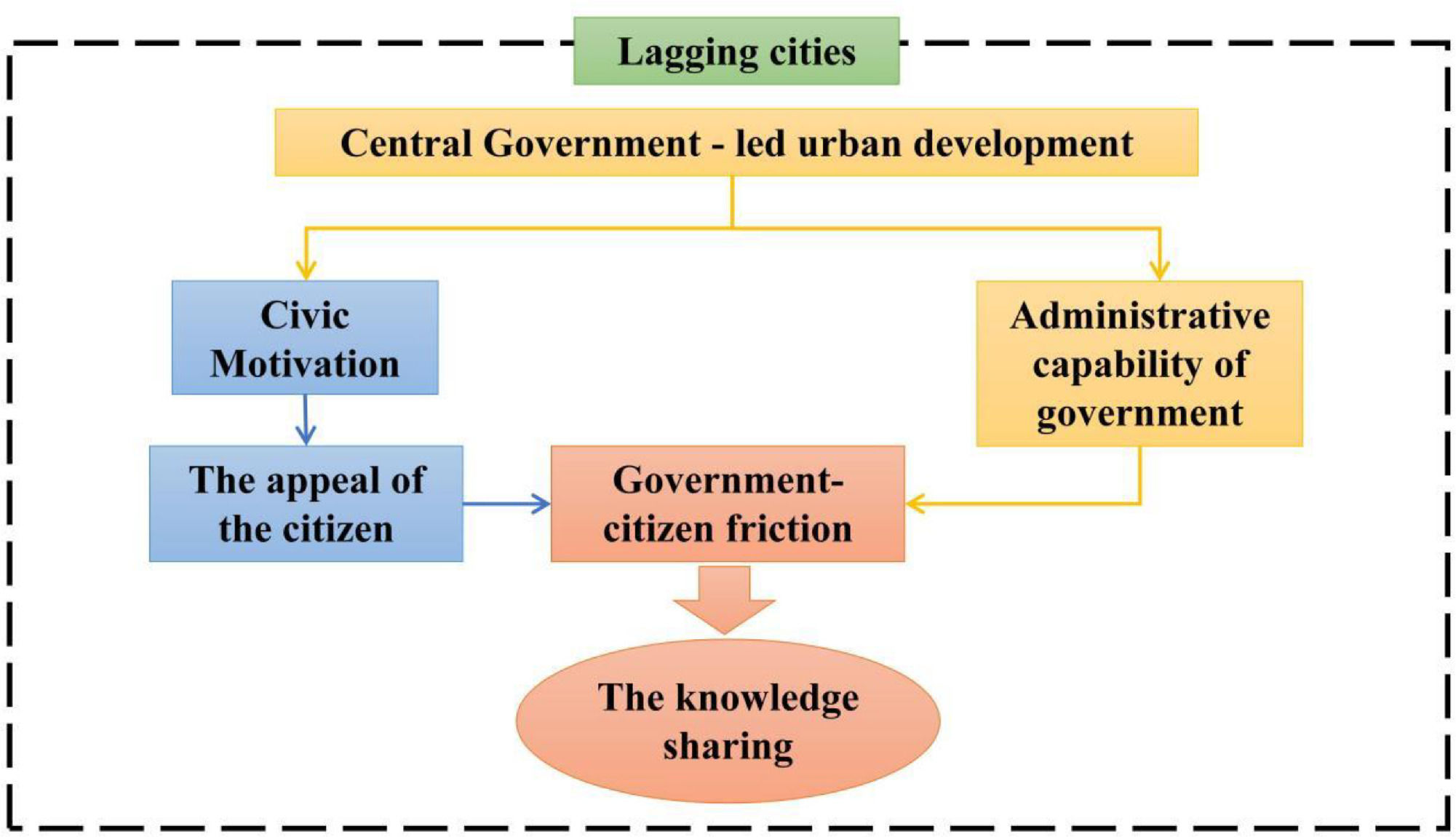

Fig. 6 illustrates how these cities have achieved KS. As with Solution 2, this solution highlights the significance of civic participation. Solution 3 differs in that it requires central government leadership. Both of the cities represented by Solutions 2 and 3 are undergoing tremendous change. In contrast to Solution 2’s economic change, the cities represented by Solution 3 are comparatively backward and have always had a low urbanisation rate. These cities develop predominantly with assistance from the central government.

Massive civic participation in this solution. The backwardness of the city encourages its citizens to express their discontent and then ‘the appeal of citizen’ generates, creating a phenomenon of high ‘civic motivation’, resulting in tensions and friction between citizens and the local governments. This friction does not directly result in government–citizens KS. When friction arises between the citizens and the local government, the mechanism for KS is activated, and the central government with the ‘administrative capability of government’ resolves the conflict by assisting the local government to transform and meet citizens’ demands, thereby facilitating effective KS between the two actors.

Robustness testIn this study, the frequency and consistency thresholds were set as 1 and 0.8, respectively. When testing the robustness of the results, after repeated verification, the combination of results do not change when the frequency and consistency thresholds are 1–2 and 0.5–0.8, respectively. Therefore, the research conclusion is robust.

DiscussionOn combinatorial factors of KSThis study identifies three solutions that result in high-quality government–citizen KS. a) Each factor presents a high level; this study describes these cities as those with better economic development, higher technological level, high citizen motivation to participate and a relationship between government and citizens, thus producing higher quality government–citizen KS; b) However, this does not mean that only cities with sound economic development can have high-quality KS interactions. c) Cities in economic or technological transition also have access to high-quality KS, which is oriented towards active citizen motivation (Thynne & Wettenhall, 2004). Compared with previous studies on single-factor causality, this study proposes a multi-factor combination of KS.

Solution 1 highlights that citizens with a high level of qualifications are motivated to participate in politics and have the capacity to translate personal knowledge into government knowledge (Perotti et al., 2022).It is crucial for the quality of citizens in mature cities that they are willing and able to participate in politics (Visser et al., 2021). The government–citizen KS was also connected with citizens’ social identification, according to a study conducted in India (Lartey et al., 2021). Increasingly, more studies have attached importance to the value of citizen quality in the government–citizen interaction (Nguyen, 2021), including citizens’ ability to absorb new information (Nguyen, 2021), the ability to express knowledge (Cummings & Teng, 2003; Nguyen, 2021) and social trust (Fischer & Döring, 2022). The citizens’ quality can reduce redundancy and the cost of administration and improve organisational performance (Jin et al., 2021; Nguyen, 2021). This solution, in which the citizens are at the core, responds to the theory of civic participation.

Solution 2 indicates that KS between governments and citizens requires neither rich personal perceptual knowledge nor a pleasant relationship between government and citizen. This government–citizen relationship appears antithetical to reality but it is also explicable. Government reform in the 21st century is increasingly dependent on civic participation (Gao & Yu, 2020; Teets, 2014). Even if the demands of the citizen are unreasonable, the elite capability of administrative personnel in the government can effectively identify the demands of citizens (Teets & Hasmath, 2020; Yue et al., 2019) to promote effective KS. However, this is only possible in cities with strong administrative capacities. This solution is especially intriguing because the government–citizen relationship is so weak. This form of government, which has a high degree of governance and can support the growth and transformation of these cities, will negatively impact the interests of some individuals who will rebel against the government and worsen the relationship between the government and citizens (Gao & Teets, 2021; Teets, 2015). In this solution, civic participation is passive. In general, civic participation excitement is quite low (S. Chen & Liu, 2022) and typically focuses on issues that are closely related to their interests (Nguyen, 2021). Citizens are involved because they are compelled to act in order to protect their interests from harm. When the society's transition is complete, citizens’ enthusiasm will wane. This level of civic participation, which is based on self-interest, is not sustainable; participation based on Solution 1’s quality of citizenship is more sustainable. Therefore, citizen quality is crucial in government–citizen KS.

Solution 3 shows how KS can be attained in developing cities through the central government-led urban development paradigm. The dramatic nature of change in these expanding and transforming communities is often what draws the most attention from the citizens and results in a phenomenon of high civic participation. The third solution emphasizes emphasises central governmental leadership. This also represents the qualities of Chinese governance, namely centralisation and decentralisation, as local governments serve as agents of the central government (Fu et al., 2022), and governance of central–local relations is the most highly centralised aspect of China's governance (Thürmer & Meyer-Clement, 2022). In addition, civic participation in this solution differs from Solution 2, where a few people's interests are harmed and they participate for their own benefit, whereas civic participation on this path involves the participation of the entire society. This type of participation is in the public interest of society and exemplifies national civic participation in governance.

KS in government–citizen interactionsThis result shows that technical knowledge is not as crucial in government–citizen KS as other scholars emphasise (Dobrolyubova, 2021; Jafari Navimipour & Charband, 2016; Khoza & Pretorius, 2017). Although cities’ internal and external environments constantly change, increasing the complexity and uncertainty of urban system evolution and making technical knowledge an important role in cities. However, it is replaceable. Solution 3 demonstrates that competent political leadership can make up for inadequate technology. This is not to argue that technology is no longer important; on the contrary, new media tools are rapidly becoming indispensable for governmental responses and public expressions (Kisielewski, 2016).

Furthermore, a harmonious relationship is not a prerequisite for KS between the government and the citizens, although previous research has demonstrated that it can facilitate knowledge contribution between the government and the citizen (Alon-Barkat, 2020; Buckwalter, 2014). However, in Solutions 2 and 3, a poor government–citizen relationship can also promote KS, which seems to contradict the findings of other studies (Choi & Cho, 2019). Therefore, we can conclude that changes in the context of specific KS render this variable fungible.

Previous research has highlighted the significance of civic participation in government–citizen interactions (Bern & Røe, 2022). The role of the citizen in governance has changed: ‘information receiver’ – ‘information provider’ – ‘customer’ – ‘partner’ (Petrovsky et al., 2017). Civic participation has deepened (Greg & Hou, 2014), and the government has placed greater emphasis on the knowledge value of its citizens. However, this result elucidates further that civic participation is differentiated. Solution 1 demonstrates that participation that is civically empowered for the generation of new knowledge is valid and continuous. However, civic participation that is formed for its own private benefit is contrary to the overall social interest (Al-Busaidi & Olfman, 2017). Petrovsky argued this participation exceeds the scope of public rights, laws and government policies will damage the government–citizen relationship, and does not generate knowledge directly (Petrovsky et al., 2017); rather, it is the catalyst for KS, as depicted in Solution 2.

ContributionThis study has three main contributions: research perspective, empirical and practical contributions. Regarding the contribution of research perspective, this study is not restricted to KS within organisations; rather, it broadens the research approach to include interactions between the government and citizens outside the government. The majority of prior research has focused on KS inside organisations (Obermayer & Toth, 2020). Therefore, when researchers examine KS in companies, they focus almost exclusively on KS inside enterprises. Such as scholars just contribute by examining the impact of KS, and managerial human capital respectively inside the company, on commitment and turnover (Lakshman et al., 2022).

Regarding the theoretical contribution, first, this study develops a framework of influencing factors of KS from various disciplines by conducting a literature review. This framework departs from the original KS in the context of internal organisation and comprehensively describes the KS variables that influence governments and citizens. Prior research focuses on KS within enterprises (Fischer & Döring, 2022) or inter-governments (Ouakouak et al., 2021), whereas KS between governments and participants outside the government has largely been ignored. With the development of the theory and practice of government response, civic participation in governance is becoming increasingly important (Yang & Chen, 2020); however, government–citizen KS has been neglected. Second, this article identifies the necessary and sufficient conditions by NCA and QCA, respectively. Previous studies have only shown the factors that have impacted KS, without comparing their importance and accurately identifying which CSFs are necessary or sufficient conditions. Third, this study determines which combinations of CSFs result in the path of KS. Most prior research has examined the factors that influence KS but not the combination of these elements. For example, only the motivation for sharing knowledge (Hsieh, 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022) or only participants in KS are investigated (Ouakouak et al., 2021). Admittedly, KS is the outcome of a combination of CSFs, not a single CSF. Therefore, this study analyses what combination contributes to high-quality government–citizen KS.

Regarding empirical contribution, this study, unlike previous studies, examines government KS at various levels, including developed and undeveloped regions. For instance, previous research has performed a broad assessment of organisations and government institutions without subdividing them into types (Ali & Gurd, 2020; Sudhindra et al., 2020). Just as firms with varying size and economic situations have significant variances, a classification study should be undertaken. So, too do the KS of governments in highly developed and less developed regions. According to the results, this study recommends KS strategies for three types of government.

ConclusionGovernment–citizen KS is crucial to the government's management innovation. Recently, the factors that influence government–citizen KS have attracted significant attention. Prior studies have focused on the effects of individual factors and have ignored the contextual and strategic factors that combine to influence the quality of government–citizen KS. Furthermore, the sufficiency and necessity of these variables for high-quality government–citizen KS have not been considered. Consequently, this study initially constructed a framework of factors influencing KS based on existing literature. Subsequently, using data from 293 municipal governmental websites in China, fsQCA and NCA were performed.

The study identified three significant results. First, design the framework of influencing factors of KS; second, identify three combinations of influencing factors to promote high-quality government–citizen KS. Additionally, five necessary and three sufficient conditions are identified. This study's contributions are as follows. First, the study viewpoint is not restricted to KS inside institutions but also includes KS between government and outside citizens. Second, it theoretically creates the framework of KS's influencing factors, determines the necessity and sufficiency of these influencing factors and provides the ideal combination of various influencing factors. Third, from an empirical perspective, this study provides three approaches to foster KS with citizens for governments that are both economically advanced and lagging behind.

This study also has several limitations. First, based on the availability of data, we selected samples only from China and excluded data from other nations. Consequently, the findings may not apply to other contexts, necessitating additional research. Second, the structural comparison method of fsQCA connects qualitative and quantitative approaches by providing a structured method for analysing the causal complexity of cases and examining the structure of cause-related variables. However, the method is still in development, and it has been criticised for issues related to data calibration and the elimination of nuance and detail from qualitative data. Therefore, future scholars should further optimise this controversy.