Inclusive entrepreneurship, which represents an integrated approach to entrepreneurship and social inclusion, has increasingly received attention for its expected capacity to simultaneously foster economic growth and mitigate inequality. This study examines how the configuration of institutional enablers, which encompass several characteristics involving markets, finance, policy, education, and knowledge, fosters inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. The results of a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis using 69 country cases indicate that institutional enablers—excluding market openness—jointly affect inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. This study provides evidence that such effects vary depending on the level of a country's economic development. As one of the first to explore the topic of inclusive entrepreneurship, this study has significant implications for academics, practitioners, and policymakers.

Entrepreneurship has always been encouraged for its long-term effects on job creation and economic development (Welter et al., 2017; Acs et al., 2016; Dabla-Norris et al., 2015; Arshed et al., 2014). However, it remains unclear how it influences inequality (Bruton et al., 2021). Furthermore, entrepreneurial activity may be limited to those who can easily access basic infrastructure and public goods, such as education and healthcare (Bruton et al., 2021). It may be restricted in some areas where access to public goods is less equitable and where the barriers to starting a business are more severe (Pilkova et al., 2016). As economic inequality has risen dramatically worldwide in recent years (Piketty, 2014), inclusive entrepreneurship has increasingly received attention as an alternative type of entrepreneurship (OECD, 2016). It represents the involvement of underrepresented or disadvantaged groups in entrepreneurial activities for their economic self-sufficiency, which is beneficial not only to themselves but also to society, as it addresses and provides equal opportunities and participation and eliminates the difficulties and social exclusion of vulnerable groups (OECD, 2013; Weidner et al., 2010; Prahalad, 2009).

Research on inclusive entrepreneurship remains limited, as it is a relatively novel phenomenon (Wu et al., 2022). Two research streams are relevant to the literature on inclusive entrepreneurship: inclusive growth and social entrepreneurship. First, inclusive growth provides a theoretical and research foundation to explore the relationship between social inclusion and economic development (Hall et al., 2012; McMullen, 2011). Research on this topic focuses on how institutions should be designed to encourage underprivileged people to start their businesses (Chataway et al., 2014; Cozzens & Sutz, 2014; George et al., 2012; McMullen, 2011). It is concerned with relevant policies—i.e., from the government's perspective—that foster sustainable growth and reduce poverty in emerging economies (Qiang et al., 2016; Joseph, 2014), seldom addressing the entrepreneur's perspective (Wu et al., 2022). Second, research on social entrepreneurship employs the logic of business to improve the situation of socially excluded and marginalized groups and presents theoretical and practical foundations for poverty reduction, minority empowerment, and inclusive growth to drive social transformation and institutional change (Saebi et al., 2019; Ghauri et al., 2014; Datta & Gailey, 2012; Alvord et al., 2004). However, this strand of the literature focuses on “social purpose” and therefore tends to overlook the general entrepreneurial purpose of underrepresented groups.

In general, inclusiveness is unquestionably a multidisciplinary issue comprising the entrepreneurial approach and other academic disciplines (Pilkova & Rehak, 2017; OECD, 2020b). Considerable gaps remain in the otherwise adequate conventional theories of entrepreneurship and the study of the new domain of inclusive entrepreneurship from a localized perspective. Previous studies have yet to articulate the dynamic nature of inclusive entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective and are therefore yet to identify what precisely promotes it (Rodrigues et al., 2022).

Prompted by the gaps in the literature, the present study explores the enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective. We present a research framework that deploys the category of entrepreneurial atmosphere as a mediator that depicts the relationships between the enablers—market openness, financial accessibility, policy affability, knowledge availability, and entrepreneurial readiness—and inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. While this study's approach is rooted in the perspective of institutional and policy design for general entrepreneurship, it also addresses similarities and differences between general and inclusive entrepreneurship. This study contributes to the existing literature in three distinct ways.

First, this study is one of the earliest of its kind to incorporate inclusiveness into entrepreneurship. Inclusive entrepreneurship—a concept first proposed by the OECD in 2013 to refer to the equality of opportunities made available to everyone in society—has increasingly gained scholarly attention (OECD, 2013; Amaro da Luz & Albuquerque, 2014). This study sheds light on this concept in both theoretical and practical terms. Second, this study explores the connection between institutional drivers and inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. Although previous studies on underrepresented groups—the youth, women, the elderly, etc.—examine the enablers of entrepreneurial activities (Pilkova et al., 2016; Sharma & Madan, 2013; Holienka & Holienkova, 2014), they limit their analysis to personal traits, including individual attitudes, competencies, and skills. The present study examines the effects of institutional enablers on inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes as mediated by entrepreneurial atmosphere. Third, this study, one of the first to employ fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fs-QCA) in the research area of inclusive entrepreneurship, corroborates previous evidence of the methodological efficacy of fs-QCA in the field. It presents fine-grained and plausible explanations for the antecedents and consequences of inclusive entrepreneurship, identifying conditions where different configurations result in the same outcomes. As a whole, this study explores an advanced research stream of inclusive entrepreneurship and avoids over-simplification to fit a linear–additive explanation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the literature on inclusive entrepreneurship and presents the study's research framework and hypotheses. Section 3 articulates the research method, including the variables and fs-QCA. Section 4 presents the results and discussion, and Section 5 concludes with academic and policy implications and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background and research frameworkInclusive entrepreneurshipInclusive entrepreneurship was first proposed by the OECD and the European Commission in The Missing Entrepreneurs: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship in Europe in 2013. It was conceived in response to the debate on the relationship between entrepreneurship and inequality, which emerged and spread in the early 2010s. Conventionally, entrepreneurship has been encouraged to drive economic growth and shape how each nation distributes the benefits of growth (Dabla-Norris et al., 2015; Lloyd-Ellis & Bernhardt, 2000). However, the last three decades have witnessed the persistence of economic inequality and wide dispersion of economic outcomes. Moreover, levels of economic inequality around the world have dramatically risen (Bapuji et al., 2020; Piketty, 2014; OECD, 2011), despite entrepreneurship becoming a worldwide phenomenon. Economies are understood to consist of two distinct sectors—the formal and the informal—each with its distinct institutional characteristics. Entrepreneurship that occurs primarily in the formal sector, the conventional domain, may result in more exclusionary institutions and increase inequality. This has led to an increased awareness of the need for an alternative entrepreneurship model that belongs in the informal sector, results in more inclusive institutions, and helps decrease inequality (Bruton et al., 2021).

Inclusive entrepreneurship is complex, dynamic, and multidimensional, with various actors interconnected in new forms of long-standing ventures (Pilkova et al., 2016). Its concepts and definitions derive from the work of various scholars and institutions and subtly differ according to their emphasis and context. However, a common ground from which to understand inclusive entrepreneurship is the engagement of underrepresented groups in entrepreneurial activities. In particular, the OECD proposes the conception of inclusive entrepreneurship as an entrepreneurial philosophy that gives all people equal opportunities to start a business and support its development, targeting marginalized and vulnerable groups, including the youth, women, the elderly, ethnic minorities, immigrants, and the disabled (OECD, 2017; Qiang et al., 2016). Based on previous studies, we conceptualize inclusive entrepreneurship as the engagement of the underrepresented or disadvantaged actors of society in entrepreneurial processes, by eliminating their social exclusion and unleashing their creative potential for self-employed work, facilitating their participation in opportunities in venture creation, and helping their start-ups become long-standing, innovative, and employable ventures.

The ultimate end of inclusive entrepreneurship is to relieve and solve the social problems of exclusion and inequality. Inclusive entrepreneurship opens up a venue for civil society to help reduce inequality and social exclusion, whether through start-ups, micro-businesses, or small enterprises. In this vein, inclusive businesses are an essential economic and social value because they are not solely for profit (de Sousa & Comini, 2012). In general, they enable the linkage of the low-income sector, particularly under-represented actors, to the market to improve their living conditions.

Research framework: institutional enablers of inclusive entrepreneurshipAlthough very few studies examine the factors that facilitate inclusive entrepreneurship, there is a consensus that institutional support, such as policies, is a significant external force for achieving it (OECD, 2016; Qiang et al., 2016; Ren & Huang, 2016). Engaging underrepresented actors in entrepreneurial activities requires institutional and structural changes to mitigate the conditions of inequality, in which opportunities are unevenly allocated across the economy. This study presents a research framework for exploring the enablers that promote inclusive entrepreneurship from an institutional viewpoint. Taking entrepreneurial atmosphere as a mediator, this study specifically posits the following enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes: market openness, financial accessibility, policy affability, knowledge availability, and entrepreneurial readiness (Fig. 1).

First, this study argues that the market structure of an economy is vital in fostering inclusive entrepreneurship. Inclusive entrepreneurship involves the accessibility of products and services, mainly because entrepreneurs from the informal sector may find it challenging to obtain official market support (Bruton et al., 2021). Nonetheless, entrepreneurs form a wide range of social associations that help them counteract prevalence criteria. The products or services offered must be competitive and sufficient to ensure the survival of underrepresented groups’ start-ups. When entry barriers are low and markets are open to new entrants, informal actors are encouraged to engage in entrepreneurial ventures. Fear of unfair competition hinders inclusivity, as it discourages entrepreneurs from participating in a wider network (World Economic Forum – WEF, 2017; Melo et al., 2013). Encouraging employability in the entrepreneurial process, particularly in underprivileged regions, brings more inclusive opportunities through market potential and information accessibility channels (Ma et al., 2021; OECD, 2016).

Second, financial accessibility refers to the provision of inclusive financial and administrative advisory support to underrepresented groups. In this respect, opportunity-based entrepreneurship implies that entrepreneurs can acquire the necessary resources. However, underrepresented groups, which usually consist of informal actors, typically face constraints in obtaining such resources. As such, new forms of entrepreneurial financing are crucial for entrepreneurs seeking to start a business; moreover, their ability to access a range of financial products and services is essential, particularly at certain stages of their ventures (Karim et al., 2021; Nizam et al., 2020; Fan & Zhang, 2017; Bruton et al., 2014).

Third, inclusive entrepreneurship should be an emphasis of governments in general because inequality is detrimental to well-being and economic development (Bruton et al., 2021). Legislation, policies, and government programs are factors that foster venture creation among underrepresented actors; as such, they should be transparent, accessible, and favorable to them. This is especially important in emerging markets, where the promotion of inclusive entrepreneurship is closely associated with national policies and institutional and resource advantages, increasingly encouraging the public, especially vulnerable groups, to participate in inclusive entrepreneurship (Choe & Lee, 2020; Dodaro, 2019; OECD, 2017).

Fourth, inclusive entrepreneurship involves creating the conditions for forming partnerships, disseminating knowledge, and popularizing the most acceptable practices of sustainable and inclusive development at the national level. In sustainable entrepreneurship, which involves start-ups, small ventures, and larger companies, entrepreneurs rely on various sources (Belz & Binder, 2017). Any strategy of economic development must be concerned with people and sustainability to address the needs of a vast number of vulnerable and marginalized people. As such, skills, knowledge, networks, and creativity development are valuable to any country-wide environment that allows the emergence and fosters the development of sustainable entrepreneurship (Argade et al., 2021; Johnson & Horisch, 2021).

Fifth, we present entrepreneurial readiness as one of the most critical institutional enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship. It encompasses institutional and infrastructural factors that cultivate human capital and the capabilities of underrepresented groups. Its key components include human capital, particularly the improvement of the capabilities and skills of current high-growth entrepreneurs and venture businesses and demand-oriented educational, technical, and vocational training services. In particular, entrepreneurship education focuses on individuals who may not be interested in starting a business. However, once they recognize an entrepreneurial opportunity and a sense of prospect, they may ultimately decide to start a business any time (Burch et al., 2019).

Following the discussion above, this study proposes the first proposition on the enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship.

Proposition 1. Market openness, financial accessibility, policy affability, knowledge availability, and knowledge readiness are the institutional enablers that play a critical role in fostering inclusive entrepreneurship. In other words, these enablers are positively associated with inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes.

Entrepreneurs may rise and fall, or assume fluid roles, permitting their ventures to incorporate materiality that may play a critical role in shaping the venture creation process (Gehman & Soubliere, 2017). In this sense, understanding this process and the social perspective of entrepreneurship leads to a better comprehension of performance in entrepreneurship (Gruber & McMillan, 2017). From this perspective, culture is an essential aspect of the entrepreneurial domain, regardless of how entrepreneurs might deploy cultural resources to legitimate their new ideas and ventures (Gehman & Soubliere, 2017).

In this study, we argue that the entrepreneurial culture and atmosphere of a society influence inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. For example, entrepreneurial culture is cultivated through a dynamic process of disseminating entrepreneurial success stories and how entrepreneurship ranks as a career choice among young entrepreneurs. Accordingly, entrepreneurial culture is affected by risks and the possibility of failure, indifferent social attitudes toward entrepreneurship, and the existence of an informal economy. This is where the pathway to decent work intersects with entrepreneurial culture. Where social and cultural norms on entrepreneurship matter, underrepresented entrepreneurs become more willing to transform their business ideas into reality (Wang & Richardson, 2021; Wry et al., 2011; Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001). This argument leads to our next proposition.

Proposition 2. The institutional enablers positively influence inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes by cultivating an entrepreneurial atmosphere..

From an institutional perspective, institutions are the primary drivers of the key differences between economies, particularly emerging and mature economies (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; Webb et al., 2010). Institutional contexts vary widely across emerging economies, each with its characteristics, which in turn constitute differences in the foundations of inclusive entrepreneurship (Bruton et al., 2021; Prahalad, 2004). For instance, the formal and informal sectors, which are widely used to characterize economies, typically shape entrepreneurial activities. The formal sector is characterized primarily by market-supporting institutions inhabited by privileged actors, whereas the informal sector represents disadvantaged and vulnerable groups whose economic activities focus primarily on subsistence (Bruton et al., 2021). The structures of the formal and informal sectors vary across countries and economies, which may affect the pathway of effects between institutions and inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes because they shape not only a person's work, but also such factors as where someone lives and with whom he/she interacts. The OECD's Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) claims that there is a linkage between entrepreneurship dynamics and an economy's institutional conditions and level of development, which either support or hinder new business creations in terms of both general and inclusive entrepreneurship (2020). GEM reports differences in inclusive entrepreneurship in economies with various levels of development: factor-driven, efficiency-driven, and innovation-driven economies (OECD, 2020a; Pilkova et al., 2016; Bosma & Levie, 2010). The level of economic development directly influences entrepreneurial opportunities, capacity, and preferences, which in turn determine business dynamics (Singer et al., 2015). Based on this argument, we put forward the next proposition on the effect of an economy's level of development on inclusive entrepreneurship.

Proposition 3. The effects of institutional enablers on inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes vary according to the level of economic development.

Inclusive entrepreneurship is a dynamic and multidimensional phenomenon consisting of complex causalities and multiple interactions between actors in the development of new forms of long-standing ventures (Pilkova et al., 2016). The institutional causal factors for inclusive entrepreneurship can be configured in different ways.

First, the dynamic nature of inclusive entrepreneurship is conditional rather than deterministic, as different configurations can lead to the same outcomes (Yao & Li, 2023). Thus, traditional linear–additive models cannot explain the causalities between the enablers and outcomes of inclusive entrepreneurship. Some institutional enablers may be necessary or sufficient to promote inclusive entrepreneurship, implying that interaction patterns and institutional conditions influence the direction of the final and desirable policy outcomes (Choi & Lee, 2020). The entrepreneurship literature has provided evidence of configurational causal conditions for fostering entrepreneurial activity. Lewellyn and Muller-Kahle (2016) demonstrate the value of using a configurational analytical technique in simultaneously exploring the micro and macro complexities of what drives women globally to engage in entrepreneurial activity. The result of their study shows that the micro-level attributes of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and opportunity recognition, combined with the macro-level formal business environment institutions and national culture, create configurations of conditions that lead to high levels of entrepreneurial activity. Zhao et al. (2023) identify an entrepreneurial ecosystem consisting of market, finance, human capital, internet access, transportation, and government, and employ fs-QCA to analyze the combined effects of multiple elements underpinning urban innovation. Their study finds the complex causal mechanism of multiple factors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, which clarifies the equivalent driving path of a high level of urban innovation. Xie et al. (2021) explore possible configurations of entrepreneurial cognition, culture, policy, finance, and education to increase female entrepreneurship. Using fs-QCA, they identify three configurations for high female entrepreneurship: the cognition–culture–dominant path, the culture–finance–dominant path, and the cognition–policy–dominant path. Douglas et al. (2021) also present configurations of antecedent conditions that constitute alternative pathways to entrepreneurial intention, and these pathways accommodate the different entrepreneurial types observed in the literature.

Second, previous studies provide evidence of configurational causal conditions leading to the same outcome in related research domains. Apetrei et al. (2019) present evidence indicating that the fundamental basis for sustainable development through entrepreneurial attitudes is closely associated with the presence of inclusive institutions and the avoidance of extractive ones. They posit that the mitigation of inequality through entrepreneurship is contingent upon a complex relationship between the entrepreneurial attitudes, institutional frameworks, and cultural variables of a given society. Cervello-Royo et al. (2022) identify a simultaneous association between a country's entrepreneurial activity and its innovation level, country risk factor, and sustainable development goals (SDG3 and SDG11). Their study emphasizes the casual combinations of innovation and financial and sustainable conditions that enhance a country's entrepreneurship level. This implies that different configurations can lead to the same outcome, rather than a single factor operating in a linear manner. In a recent study, Yu and Huarng (2024) examine the causal complexity of the achievement of sustainable development goal. They posit a threefold proposition comprising a set of antecedents, including digital technology, transparency and integrity, innovation, entrepreneurship, economic growth, and financial technology. They claim that these factors can collectively enhance a country's sustainability level. Muñoz and Kibler (2016) employ fs-QCA to investigate the impact of institutional factors on social entrepreneurship. Their results indicate the existence of multiple causal paths in both formalized and less formalized contexts, thereby reinforcing the idea of multiple conjunctional causation. To illustrate, even though less formalized institutional structures appear to be more influential than formal regulations and support, a single informal institutional condition is inadequate to offset the central impact of the perceived influence capacity of local bodies on the opportunity confidence of social entrepreneurs.

Third, the specific configurations of institutions that encourage inclusive entrepreneurial activity may vary according to the country's context. Using regression and fs-QCA, Velilla and Ortega (2017) demonstrate the existence of disparate configurations of the requisite and sufficient entrepreneurial determinants in developed and developing countries. For example, whereas the principal determinants in developed countries are education and technological equity, individuals in developing countries are inclined to become entrepreneurs irrespective of their macroeconomic context. Beynon et al. (2016) employ fs-QCA with data from the GEM 2011 survey to investigate entrepreneurial attitudes and activity. Their findings identify discrepancies in the potential combinations of factors influencing entrepreneurship across individual countries at varying stages of economic development. For example, growth-enhancing policies may be the most relevant institutional enabler in innovation-driven countries. Beynon et al. (2020) also provide evidence of the potential impact of combinations of several factors on entrepreneurial activity in different types of national economies over time. They present the heterogeneous experiences of developing and developed economies as two distinct groups experiencing changes in total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) and associated causal configurations over time.

Based on this argument, we propose the following proposition on the interactions of the institutional enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship.

Proposition 4. The effects of institutional enablers on inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes form configurations according to their interactions.

Research methodologyfs-QCAThis study employs fs-QCA—a method that is still in its early stages but which has recently received more attention in the fields of innovation and entrepreneurship (Chen & Tian, 2022; Du et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2018)—for several reasons.

First, QCA is suitable for studying complex causalities and multiple interactions because it is a configurational approach based on set theory and fuzzy algebra (Ragin, 2008; Fiss, 2011; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). In particular, it can be used to articulate complexities and explain how the interactions of conditions result in expected outcomes (Huang et al., 2023). This approach comprehends the complexities of managerial and organizational phenomena and facilitates the examination of the configuration of lower-level characteristics that constitute higher-level constructs (Misangyi et al., 2017), as in the case of inclusive entrepreneurship. Second, based on an asymmetric data analysis technique, this approach has the advantages of both qualitative and quantitative analysis methods. QCA combines the logic and empirical strength of qualitative approaches, which are rich in contextual information, with quantitative approaches, which can deal with sizable numbers and generalize from specific cases (Ragin, 2008; 2006). Third, QCA is outcome-oriented and can determine whether specific conditions are necessary to achieve desirable outcomes (Du & Kim, 2021; Misangyi et al., 2017). In particular, fs-QCA can efficiently handle the exponentially cumulative complexity of a configurational perspective by deriving fuzzy sets. Overall, it is suitable for examining whether institutional enablers are necessary or sufficient to achieve a higher level of inclusive entrepreneurship using sizable numbers of national-level cases from the OECD's GEM.

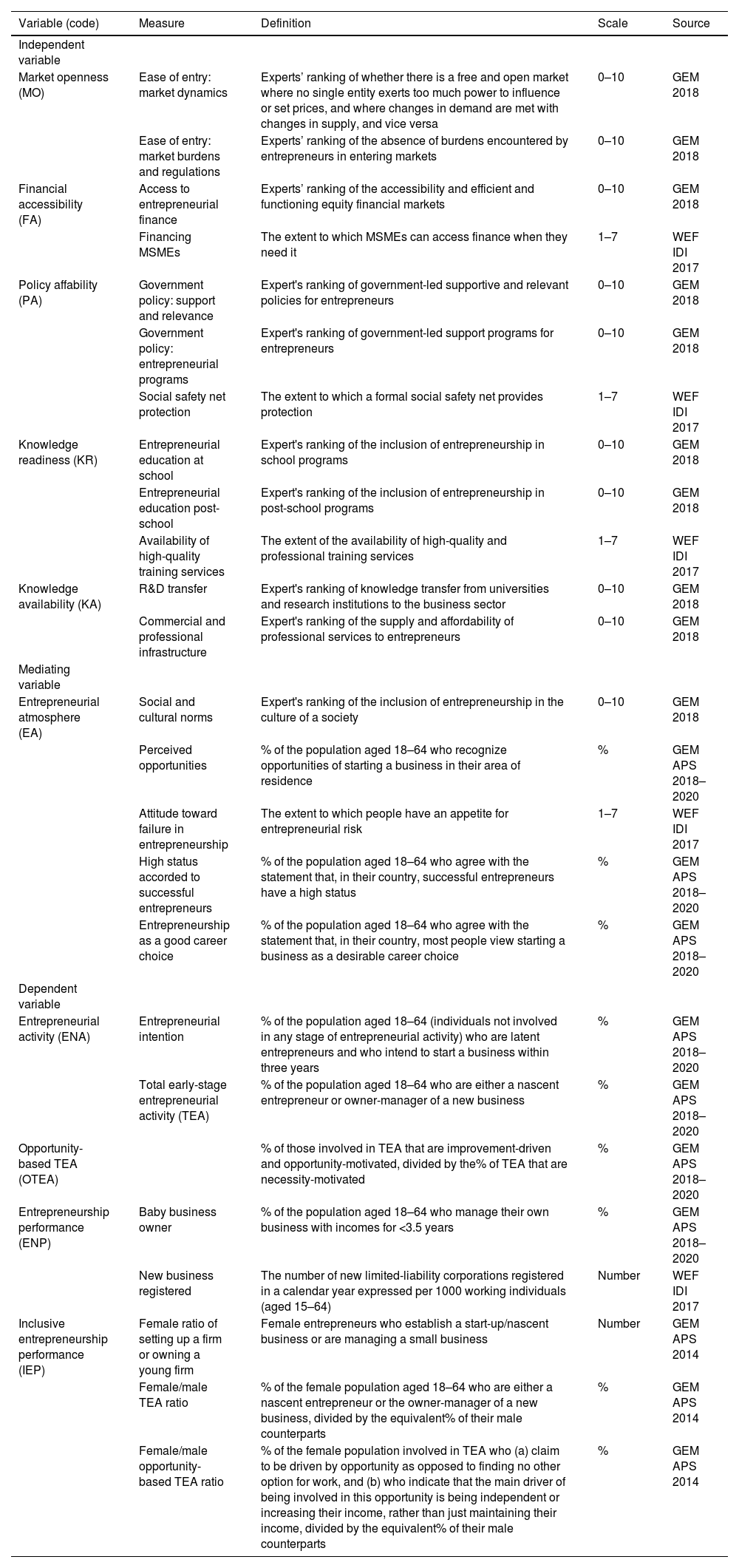

Measurement and sampleThis study proposes five independent variables as institutional enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship, one mediator, and four dependent variables as inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. Institutional enablers include market openness, financial accessibility, policy affability, knowledge readiness, and knowledge availability. First, market openness refers to the ease with which entrepreneurs enter the market. It indicates the existence of a free and open market where no single entity exerts too much influence, as well as the level of burdens and regulations entrepreneurs encounter upon entering markets. In particular, two items—“ease of entry: market dynamics” and “ease of entry: market burdens and regulations”—are used to measure market openness based on the expert ratings of the entrepreneurial framework conditions of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor GEM (2022). Second, financial accessibility characterizes an economy's financial channels and infrastructure that support entrepreneurs. It is measured using two indicators: experts’ ranking of access to entrepreneurial financing based on GEM and financing based on the World Economic Forum's Inclusive Development Index (WEF IDI). Third, policy affability refers to the relevance of policies implemented to support potential entrepreneurs and ensure their social safety. Three items are used to measure policy affability: experts’ ranking of government policy and entrepreneurship programs based on GEM and the social safety net protection indicator of WEF IDI. Fourth, knowledge readiness indicates how a society cultivates latent entrepreneurs through education and training. It is measured using three items: experts’ ranking of entrepreneurial education at school and post-school settings based on GEM, and the availability of high-quality training services indicator of WEF IDI. Fifth, knowledge availability denotes how entrepreneurs can easily access and utilize relevant and necessary knowledge. It is measured using two items: experts’ ranking of R&D transfer and commercial and professional infrastructure, both based on GEM.

The dependent variables of inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes consist of four constructs. First, entrepreneurial activity is measured using two items: the entrepreneurial intention indicator and TEA of the adult population surveys of GEM (GEM APS). Second, opportunity-based TEA (OTEA) is measured using the motivational indicator of GEM APS. Third, general entrepreneurship performance is a composite of two items: the baby business owner indicator of GEM and the new business register indicator of WEF IDI. Fourth, inclusive entrepreneurship performance is measured using three items: the female ratio of new ventures, female ratio of TEA, and female ratio of OTEA from GEM APS. This study employs entrepreneurial atmosphere as a mediator between institutional enablers and outcomes. This construct is measured using five items: the social-cultural norms indicator of GEM, the perceived opportunity indicator, the entrepreneur status indicator, the promising career choice perception indicator of GEM APS, and the attitude toward failure indicator of WEF IDI.

A sample was compiled from the WEF IDI, GEM, and GEM APS datasets. This study used the 2017 index of WEF IDI, the 2018 index of GEM, and the 2018, 2019, and 2020 indices of GEM APS. We only included samples that record measures of at least one item for each construct within the sample period. Thus, a total of 69 observations at country level were used. We categorized sample countries into four groups according to their level of economic development: advanced (number of cases = 24), second-advanced (number of cases = 15), upper-middle-income (number of cases = 16), and low-income countries (number of cases = 14). Table A1 in the Appendix details the constructs and measures used in this study.

CalibrationCalibration involves transforming variables into a set membership, ranging from full non-membership that equals 0 to full membership that equals 1; 0.5 is the crossover point and indicates maximum ambiguity (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012; Kraus et al., 2018). This calibration method employed in this study is based on the sample maximum, mean, and minimum (Fiss, 2011; Misangyi et al., 2017). Fs-QCA captures two types of conditions: those that are sufficient or necessary to explain an outcome and those that are insufficient on their own but are necessary to explain the results (Fiss, 2011). The actual sample distribution deviated from the scale anchors, so we reconciled the conceptual anchors with the actual distribution of the sample (Fiss, 2011; Misangyi et al., 2017). We set three anchor points—fully in, crossover point, and fully out—according to the sample maximum, mean, and minimum values. For example, we calibrated the 95 % for the “fully in” set of high performance and the 5 % for the “fully out” set. The crossover point was 50 %. To avoid theoretical difficulties at maximum ambiguity (0.5), we added a small constant of 0.001, following established practices (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008). Table 1 presents a summary of this study's statistics and calibration.

Summary of statistics and calibration.

Note: The table shows the numerical scores for the measures, which range from 0 to 100, following the Baldrige criteria. That is, we set the scores 95, 50, and 5 as the anchors for full membership, crossover, and full non-membership, respectively, for the high-performance set.

We used the fs-QCA3.0 software to analyze the standardized data. This instrument is capable of capturing (1) conditions that are sufficient or necessary to explain outcomes and (2) those that are insufficient on their own, but (3) are necessary parts of the solutions that can explain the results. Following previous studies, we analyzed sufficiency using the minimum case frequency benchmark ≥1 (De Crescenzo et al., 2020; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012) and raw consistency benchmark ≥0.8 (Du & Kim, 2021; Fiss, 2011). We also applied proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) to further filter out the truth table rows, which are reliably linked to the outcome (Greckhamer et al., 2018; Du & Kim, 2021). We followed three steps in conducting fs-QCA. First, using set measures (i.e., independent and mediating variables), fs-QCA generated the data matrix of a truth table with 2k rows, where k is the number of causal conditions (i.e., combinations of variables) used in the analysis. Each row is associated with a specific combination of variables, and the full table lists all the possible combinations. In the second step, fs-QCA eliminated the rows according to sufficient, necessary, and insufficient solutions. In the third step, a Boolean algebra algorithm logically reduced the truth table rows and yielded the simplified and most potent combinations. Derived from a counterfactual analysis of causal conditions, the algorithm was used to classify the causal conditions representing the core and peripheral causes of the variables (Ragin, 2008).

This study used a truth table algorithm to distinguish between parsimonious and intermediate solutions based on “easy” and “difficult” counterfactuals (Ragin, 2008). “Easy” counterfactuals refer to situations where a redundant causal condition is added to a set of extant conditions. “Difficult” counterfactuals indicate situations where a certain condition is removed from a set of causal conditions. Causal conditions are classified into three categories: core, conditional, and peripheral. Core and conditional conditions are part of both parsimonious and intermediate solutions, and a peripheral condition is eliminated in the parsimonious solution and therefore appears only in the intermediate solution (Fiss, 2011).

Results of the analysisThis study applied fs-QCA to a sample of 69 countries to examine whether or not institutional enablers affect inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. The sample was classified into four distinct country contexts: advanced, second-advanced, upper-middle-income, and low-income economies.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the fuzzy-set solution for the total sample. The evidence derived from the fs-QCA solution is not strong enough to indicate that institutional enablers have significant relationships with entrepreneurship outcomes. For instance, financial accessibility (FA), policy affability (PA), knowledge readiness (KR), and knowledge availability (KA) are conditional causal conditions, implying that their effects may be significant—but not always—to entrepreneurial activity (ENA) and opportunity-based TEA (OTEA) (see 1a in Table 2). However, FA and PA are critical to fostering entrepreneurship performance (ENP) (see 1b in Table 2). This result also indicates that PA, KR, and KA are crucial in facilitating inclusive entrepreneurship performance (IEP) (see 1c in Table 2). Significantly, entrepreneurial atmosphere (EA) affects entrepreneurship performance. In addition, PA, KR, and KA on IEP emerge as core causal conditions in which entrepreneurial atmosphere (EA) joins the solution (i.e., 1a → 1c), indicating that social norms and culture can mediate the effects of institutional enablers on entrepreneurship outcomes. However, this result indicates that market openness (MO) is a peripheral condition: it does not have a direct and significant relationship with entrepreneurship outcomes. Overall, this result provides partial support for the first and second propositions.

Configurations strongly related to inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes in a global context.

Note: 1a represents a solution of [∼MO*∼FA*∼PA*∼KR*∼KA*EA]; 1b represents a solution of [∼MO*FA*PA*∼KR*∼KA*EA]; 1c represents a solution of [∼MO*∼FA*PA*KR*KA*EA]1; ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition.

Table 3 presents the results of a fuzzy-set solution for an advanced economy. This result indicates that FA, PA, and KR are essential to entrepreneurship outcomes, specifically ENA, OTEA, ENP, and IEP. The solution (2b in Table 3) in which FA, PA, and KR are core causal conditions (i.e., noted as *FA*PA*KR) implies that inclusive entrepreneurship can be promoted through accessible financing for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), supportive government policy and programs, and entrepreneurial education and training, a result that is in line with our expectation. Furthermore, these institutional enablers emerge as a core causal condition when EA joins the solution (i.e., 2a → 2b), indicating the latter's mediating role. However, MO is a peripheral condition in the advanced country context. Moreover, KA is shown to be a conditional causal condition, implying that it may have an effect, but not always, on entrepreneurship outcomes.

Configurations strongly related to inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes in advanced countries.

Note: 2a represents a solution of [∼MO*∼FA*∼PA*∼KR*∼KA*∼EA]; 2b represents a solution of [∼MO*FA*PA*KR*∼KA*EA]; ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition.

This study analyzes the fuzzy-set solution by classifying country contexts based on their GDP per capita; the second-advanced economy context has a GDP per capita ranging from USD 17,000 to 30,000. Table 4 summarizes the results of the fuzzy-set solution for the second-advanced country context. For the ENA and OTEA outcomes, PA, KR, and EA are core causal conditions, with the absence of MO and KA. For this group, MO may be better when it is absent.

Configurations strongly related to inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes in second-advanced countries.

Note: 3a represents a solution of [∼FA*PA]; 3b represents a solution of [∼FA*KR]; 3c represents a solution of [∼KR*EA]; 3d represents a solution of [∼MO*FA*PA*KR*∼KA*EA]; 3e represents a solution of [MO*FA*PA*KR*KA*EA]; ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition; ⊗ = absence of a solution.

The results for the upper-middle-income economies show that the institutional enablers have significant relationships only with ENP. In particular, FA, PA, and KR influence ENP; however, KA and MO do not seem to foster entrepreneurship outcomes since they are conditional and peripheral causal conditions, respectively (see 4b in Table 5). The results show that EA is a core causal condition, indicating that the social and cultural norms and perceptions of entrepreneurship play a dominant role in fostering entrepreneurship performance in upper-middle-income countries (Table 5).

Configurations strongly related to inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes in upper-middle-income countries.

Note: 4a represents a solution of [∼MO*∼FA*∼PA*∼KR*∼KA*EA]; 4b represents a solution of [∼MO*FA*PA*KR*∼KA*EA]; ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition.

Table 6 presents the results of the fuzzy-set solution for the low-income economy group. The results are similar to those for the upper-middle-income economy group. FA, PA, KA, and KR are core causal conditions for the ENP outcome. MO is the absence of a solution in this configuration, implying that it may be better when this enabler is absent. These four variables are conditional causal conditions for the ENA and OTEA outcomes, indicating a possible significant but contingent impact. As in other economic contexts, the results confirm that EA significantly impacts entrepreneurship performance.

Configurations strongly related to inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes in low-income countries.

Note: 5a represents a solution of [∼MO*∼FA*∼PA*∼KR*∼KA*EA]; 5b represents a solution of [MO*FA*PA*KR*KA*EA]; ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition; ⊗ = absence of a condition.

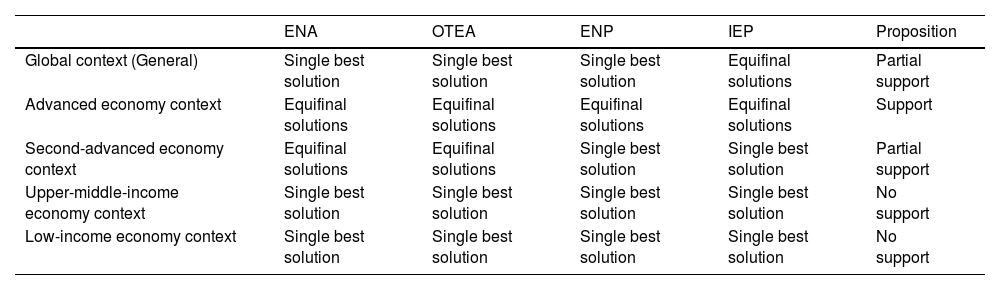

The results of fs-QCA provide evidence of how institutional enablers foster inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes. Table 7 summarizes the results of the analysis. First, in the global context (the general model), the results partially support our first and second propositions. Some, but not all, institutional enablers significantly affect some of the outcomes. FA and PA are core causal conditions that foster entrepreneurship performance; and PA, KR, and KA are significantly associated with inclusive entrepreneurship performance. At the same time, MO is a peripheral causal condition. EA, the most influential factor in inclusive entrepreneurship, also plays a mediating role through which PA, KR, and KA enhance IEP. The results of fs-QCA across the four groups of economies illustrate that the effects of institutional enablers on entrepreneurship outcomes vary, which supports our third proposition regarding the contingent model.

Summary of the results and proposition test.

Note: ⬤ = core causal condition; • = conditional causal condition; ∼ = peripheral causal condition; ⊗ = absence of a condition.

Applying the fs-QCA method extends the earlier findings on the enablers of inclusive entrepreneurship, reached through other methodological approaches, typically based on regression and structural equation models. Complex mechanisms underpin inclusive entrepreneurship through the interactions between institutional enablers—market openness, financial accessibility, policy affability, knowledge readiness, knowledge availability—and entrepreneurial atmosphere. Table 8 presents the study's findings, which suggest multiple paths toward inclusive entrepreneurship, with a single best solution leading to the equifinality phenomenon. First, in the global context (the general model), a single best solution is identified for improving ENA, OTEA, and ENP, while two different configurations of institutional enablers lead to the same desired outcome regarding IEP. The configuration consisting of a core causal condition of EA with conditional causal conditions of FA, PA, KR, and KA exerts the same influence on inclusive entrepreneurial performance, as that of the core causal conditions of PA, KR, KA, and EA with a conditional causal condition of FA. Second, the equifinality phenomenon becomes apparent in the context of an advanced economy. The two configurations both result in the same levels of ENA, OTEA, ENP, and IEP. Third, in the context of a second-advanced economy, three distinct patterns of causal conditions are identified as producing the outcomes of ENA and OTEA; however, only a single optimal solution emerges for ENP and IEP. Fourth, the results indicate the best solution for all entrepreneurship outcomes in upper-income and low-income economies. This may imply a generalized pattern in facilitating entrepreneurship at an early stage of economic development. These findings demonstrate the dynamic nature of the mechanisms promoting general and inclusive entrepreneurship, which combine single optimal and equifinal solutions.

Summary of the results and configurations.

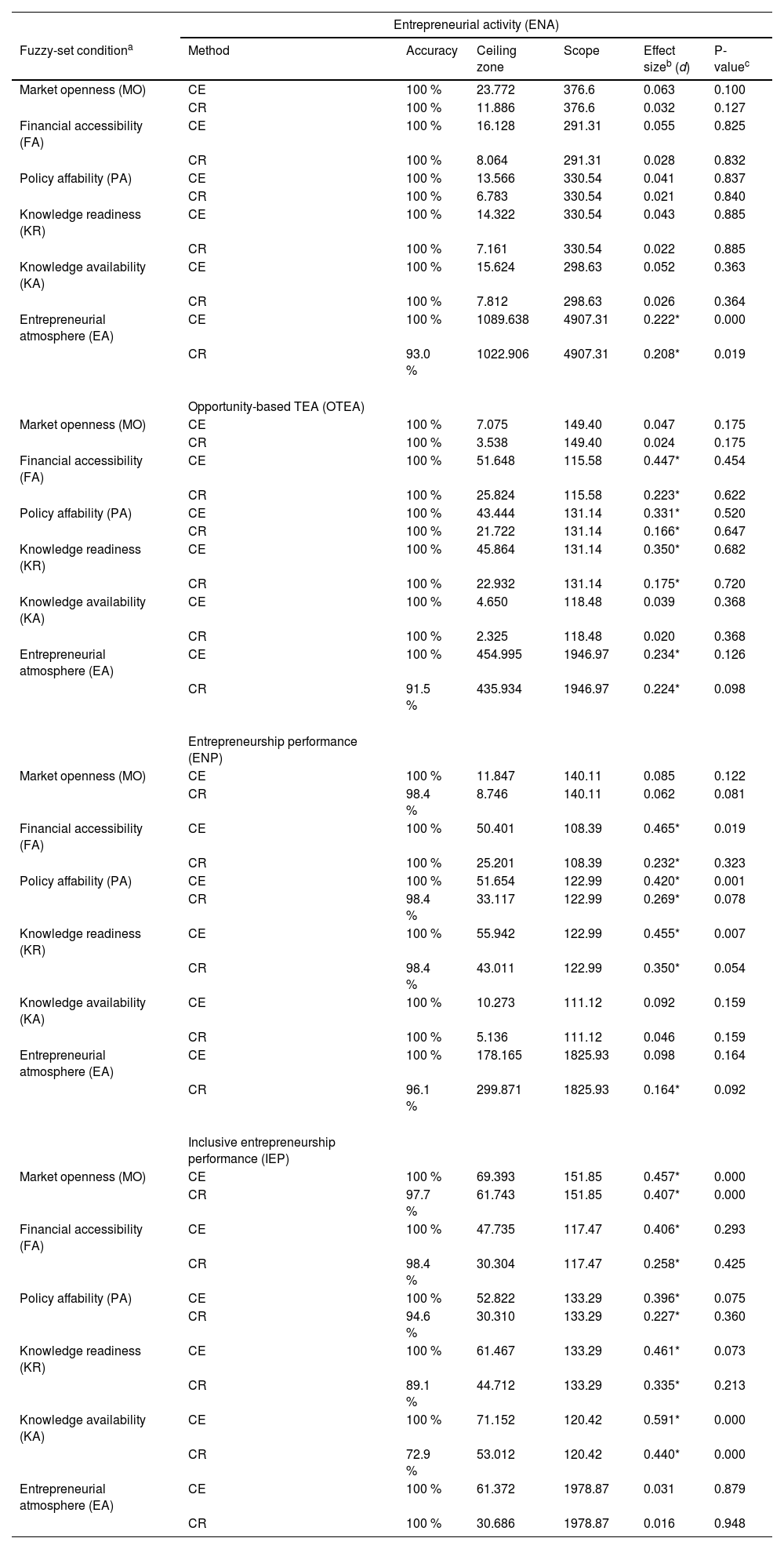

We employed necessary condition analysis (NCA) to confirm our results and examined any latent necessary conditions leading to the same outcomes. NCA is another approach that comprehends causality in terms of necessity and sufficiency, focused on (levels of) single determinants (and their combinations) that are necessary but not automatically sufficient (Dul, 2016; Ragin, 2008). It identifies the range of necessity rooted in calculus, which is not available in fs-QCA (Du & Kim, 2021; Vis & Dul, 2018), without any pre-calibration (Richter et al., 2020). It adds to the insights obtained through fs-QCA by yielding more precise results (Richter et al., 2020; Vis & Dul, 2018; Dul, 2016).

Table 9 summarizes the NCA results using the two procedures for calculating necessary effect sizes: ceiling envelopment (CE) and ceiling regression (CR). Accuracy represents the number of cases on or below the ceiling line divided by the total number of cases. The necessity effect size d is calculated by dividing the empty space (ceiling zone) by the entire area that can contain observations (scope) (Du & Kim, 2021; Dul et al., 2020; Richter et al., 2020; Vis & Dul, 2018), indicating whether or not a variable or construct is a necessary condition. In NCA, a condition is necessary when its effect size d is equal to or greater than 0.1 (Dul, 2016).

NCA results in the global context.

Note: NCA procedures are taken directly from Dul (2016): (a) Membership scores are used instead of values in raw variables. (b) The extent to which a condition is necessary is expressed with the effect size d (general benchmark 0 ≤ d < 0.1 small effect, 0.1 ≤ d < 0.3 medium effect, 0.3 ≤ d < 0.5 large effect, and d ≥ 0.5 very large effect). (c) NCA analysis with the permutation test (resampling =10,000); *d ≥ 0.1.

The results of NCA generally confirm that our findings are robust, indicating that the configurations of institutional enablers that foster inclusive entrepreneurship are consistent at the highest level in the categorized country cases. We also conducted a robustness analysis following previous studies (Yao & Li, 2023; Huang et al., 2023), which presented a consistency level ranging from 0.8 to 0.81. This result indicates that the scope and consistency of the study's overall solutions are relatively robust (Schneider & Wagemann, 2010).

ImplicationsAcademic and theoretical implicationsBy examining the effects of institutional enablers on inclusive entrepreneurship outcomes using fs-QCA, this study makes several contributions to the literature.

First, this study is one of the first to explore inclusive entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective. Inclusive entrepreneurship has emerged as a worldwide phenomenon, raising expectations of its capacity to facilitate economic growth and mitigate inequality simultaneously (OECD, 2013; Prahalad, 2009). As it has become part of the economic agenda pursued by many countries only recently, very little academic work has been done on this topic. Entrepreneurship focusing on underrepresented groups in society should be approached differently from general entrepreneurship (Wu et al., 2022). For instance, necessity-based start-ups, which include inclusive entrepreneurs in the informal sector, may not, under the circumstances, be the same as opportunity-driven start-ups composed of typical entrepreneurs. Such heterogeneity in entrepreneurship has not been fully acknowledged and addressed. This study sheds light on the dynamic nature of inclusive entrepreneurship.

Second, the research framework of this study provides a better understanding of how inclusive entrepreneurship can be enhanced through institutional enablers. Although many studies focusing on underrepresented groups examine the enablers of entrepreneurial activities, they are limited to entrepreneurs’ personal traits. The present study demonstrates how institutional enablers and a society's entrepreneurial atmosphere interact to generate desirable entrepreneurship outcomes. The empirical evidence of the relationships between institutional enablers—market, finance, policy, education, knowledge, and social atmosphere—and inclusive entrepreneurship can provide a theoretical and empirical foundation for further research. Furthermore, this study extends the scope of the literature by confirming that the institutional enablers of higher inclusive entrepreneurship vary depending on the economic context.

Third, as one of the first to employ fs-QCA in inclusive entrepreneurship research, this research provides evidence that inclusive entrepreneurship can be driven by combinations of factors and independent effects. The existing literature on inclusive entrepreneurship has concentrated on identifying the impact of individual factors that can improve its outcomes (e.g., Ma et al., 2021; Karim et al., 2021; Wang & Richardson, 2021). The fs-QCA method can address the issue of equifinality, which is often overlooked in management studies (Nowiński & Haddoud, 2019), and identify patterns of causal conditions that produce the outcome (Stroe et al., 2018). It is the most suitable analytical approach to conducting a novel systematic analysis of early-stage social entrepreneurs (Muñoz & Kibler, 2016). Relative to traditional statistical models, fs-QCA is an appropriate method of addressing the question of how to discover different configurations of multiple interrelated variables, all of which are directed toward the same desired output (Kraus et al., 2018; Douglas et al., 2020; Laouiti et al., 2022). This study offers more detailed and plausible explanations, revealing subtle nuances within the sample and identifying conditions where different configurations of institutional enablers lead to the same outcomes of inclusive entrepreneurship. In conclusion, this study paves the way for an advanced research stream that explores emerging issues in the inclusive entrepreneurship domain, avoiding the pitfalls of oversimplification and linear–additive explanations (Ding, 2022).

Fourth, this study can serve as a foundation for the rigorous empirical study of inclusive entrepreneurship. Researchers on inclusive entrepreneurship at a national level may encounter the problem of insufficient sample cases, such as longitudinal panel data. We propose several measures for the institutional enablers and outcomes of inclusive entrepreneurship using—and combining—accessible datasets, including GEM and WEF IDI, which can be utilized when designing and conducting empirical research.

Policy and practical implicationsThis study presents significant implications for policymakers who aim to foster inclusive entrepreneurship by providing underrepresented social groups with better opportunities to start their opportunity- and necessity-based ventures.

First, the results of this study indicate that accessible finance, affable policy, knowledge readiness, and available knowledge enhance inclusive and general entrepreneurship performance. Underrepresented groups face barriers to accessing necessary and relevant financial resources in starting a business. Governments must devise new forms of entrepreneurial financing and lower such barriers by providing financial products and assistance services to MSMEs. Governments should reform their entrepreneurship policies by classifying entrepreneurs into two different categories: general opportunity-based entrepreneurs and inclusive necessity-based entrepreneurs. Policies should guarantee disadvantaged groups access to relevant and necessary assistance, protect them from potential exploitation by established groups, and provide social safety net protection, particularly for latent entrepreneurs to overcome their fear of failure. Education and training are vital to inclusive entrepreneurship because they cultivate the human capital of underrepresented groups and improve their capability to start and sustain their opportunity- and necessity-based businesses. OECD and WEF also urge governments to increase entrepreneurial education at school and post-school settings and provide disadvantaged groups with high-quality training services. Governments should facilitate the dissemination and free flow of knowledge and information among less-privileged groups in society, because inclusive entrepreneurs (e.g., informal actors in the economy) rely on external sources of knowledge more than general entrepreneurs (e.g., formal actors in the economy) do. Thus, policymakers should guarantee that vulnerable and marginalized groups can easily access and benefit from information and knowledge.

Second, entrepreneurial atmosphere is a dominant factor in fostering inclusive entrepreneurship regardless of the level of economic development. Social and cultural norms are not established overnight and without the cooperative action of all actors in society; however, policymakers should lay the foundation for a pro-entrepreneurship social culture. The GEM initiative and WEF provide some criteria for a robust social entrepreneurial atmosphere, including perceptions of entrepreneurial opportunities, the high status of successful entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship as a good career choice, and a fearless attitude toward failure in entrepreneurship. These are relevant to inclusive entrepreneurship because underrepresented entrepreneurs become more willing to transform their business beliefs into reality when social and cultural norms on entrepreneurship matter.

Third, this study highlights developed and developing economies’ disparate experiences of inclusive entrepreneurship and the associated causal configurations. To illustrate, the capacity for finance, policy, and knowledge readiness is significant in all entrepreneurship outcomes in advanced countries. However, the effect of these same enablers on entrepreneurship performance is limited. The impact of institutional enablers appears to diminish as national income declines, suggesting that policies designed to promote inclusive entrepreneurship in advanced countries must be carefully considered and planned. By contrast, policies of less advanced countries (e.g., middle- and low-income economies) should concentrate on particular and practical measures to ensure the effective deployment of their limited budget resources. This study presents several configurations of institutional enablers that result in the same outcomes according to the national economy's status. Policymakers should select a pathway that aligns with their countries’ specific conditions rather than promoting all institutional dimensions with equal emphasis. It is acknowledged that different countries may possess various resources and competitive advantages. Thus, countries should adopt causal relationships that align with their socio-economic realities to promote inclusive entrepreneurship. By revealing countries with similar configurations of conditions, this study's results help policymakers identify countries that can potentially serve as a benchmark (Beynon et al., 2018).

ConclusionInclusive entrepreneurship, as an integrated approach to entrepreneurship and inclusive economy, has increasingly received attention, with expectations for its capacity to simultaneously foster economic growth and mitigate social inequality. However, research on how to foster inclusive entrepreneurship remains at a very early stage. This study examines how institutional enablers ranging from the market, finance, policy, education, and knowledge foster inclusive entrepreneurship, with entrepreneurial atmosphere taken as a mediator.

The fs-QCA method using the GEM and WEF databases provides evidence that all institutional enablers—except market openness—significantly influence entrepreneurship outcomes, particularly entrepreneurial activity and general and inclusive entrepreneurship performance. The results illustrate that such effects vary depending on the status of a country's economy, implying that policy measurements for inclusive entrepreneurship should be applied differently. This study also shows that the social norms and culture governing entrepreneurship play a critical role in facilitating inclusive and general entrepreneurship. As one of the first studies on inclusive entrepreneurship, this research provides significant implications for academics, practitioners, and policymakers.

By indicating some of its limitations, this study suggests directions for future research. First, while this study sheds light on the research on and practices in the intersections of entrepreneurship and inclusive economy, there is a deficit of theoretical work to help us better understand the dynamic nature of inclusive entrepreneurship. This study does not clarify the similarities and differences between general and inclusive entrepreneurship. Most of all, the concept, definition, and measurement of inclusive entrepreneurship should further be elaborated through critical reviews of the literature and be grounded on theory based on in-depth case-based research. Second, this study focuses on the institutional factors of inclusive entrepreneurship at a national level of analysis. There may be a wide range of other factors from individual and organizational levels of analysis. Future research should extend the framework of this study, while incorporating other plausible explanations and theories on entrepreneurship. For instance, the resource-based view, social capital theory, and social network theory from an organizational level of analysis can be employed to conceptualize an inclusive entrepreneurship theory. Third, this study utilizes data compiled from the GEM and WEF. Although the data sources for inclusive entrepreneurship are very limited, future research should develop and generate more relevant data dedicated to this topic. Valid and reliable measurements of inclusive entrepreneurship should also be developed. Hopefully, further longitudinal studies are conducted to explore dynamic changes in inclusive entrepreneurship worldwide. Fourth, as one of the first studies to employ a qualitative comparative research method, the results of this study may be vulnerable to data sensitivity. The fs-QCA method, as a configurational approach, is suitable for exploring the antecedents and consequences of inclusive entrepreneurship, consisting of complex causalities and multiple interactions (Yao & Li, 2023). By combining the fs-QCA method with conventional hypothesis-testing methods, such as regression and structural equation modeling, future research can extend our limited understanding of necessity and sufficiency conditions to promote inclusive entrepreneurship (Ding, 2022). As the number of studies using fs-QCA grows, it is increasingly critical to follow the preprocessing data and perform analysis rigorously (Nikou et al., 2024).

FundingNo Funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAaron A. Vargas-Zeledon: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Su-Yol Lee: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Variables, measures, and data sources.