Autoimmune hepatitis is a rare inflammatory liver disease rarely considered in the older patient, although current evidence has shown it can occur across all ages. Physicians must be aware of the particularities of disease presentation and management in older adults.

The authors describe a 77-year old female patient who presented with persistently elevated liver function tests and was found to have type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. After initiation of treatment, the patient went into clinical and biochemical remission, which persisted after treatment suspension, with no evidence of relapse, to date.

Although conventional regimens have been shown to be highly effective in achieving remission in the elderly, further studies are warranted to best address the needs of this subgroup of patients and establish the most effective and safe treatment protocols.

La hepatitis autoinmune es una rara enfermedad inflamatoria del hígado que rara vez se plantea en el paciente de edad avanzada, aunque las pruebas actuales han demostrado que puede ocurrir en todas las edades. Los médicos deben ser conscientes de las particularidades de la presentación y el tratamiento de la enfermedad en los adultos mayores.

Los autores describen a una paciente de 77 años que se presentó con pruebas de función hepática persistentemente elevadas y se le detectó una hepatitis autoinmune de tipo 1. Después de iniciar el tratamiento, la paciente entró en remisión clínica y bioquímica, que persistió después de la suspensión del tratamiento, sin que hasta la fecha haya habido pruebas de recaída.

Aunque se ha demostrado que los regímenes convencionales son muy eficaces para lograr la remisión en los ancianos, se justifica la realización de más estudios para atender mejor las necesidades de este subgrupo de pacientes y establecer los protocolos de tratamiento más eficaces y seguros.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare chronic necro-inflammatory disease of unknown cause, with a highly heterogeneous phenotype. It has an estimated incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 persons, women being more affected than men (3.6:1 ratio). Previously considered a disease of the young adult, it is now known to occur commonly across all ages. There are only a few studies describing AIH in the elderly patient, who are more likely to be asymptomatic and to present with cirrhosis.1 The diagnosis can be made using clinical and biochemical features and/or by liver biopsy. Treatment in this subgroup of patients with glucocorticoids, azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine has been shown to be as effective as in younger patients (although the most appropriate regimens remain to be determined by clinical trials). Most authors recommend a lower dose of glucocorticoids in the induction phase (0.5 vs. conventional 1mg/kg/day), considering the risk for corticogenic side effects, the possibility of other comorbidities and interaction with other medications. AIH in the older patient has been found to be more indolent with lower treatment failure rates.2–4

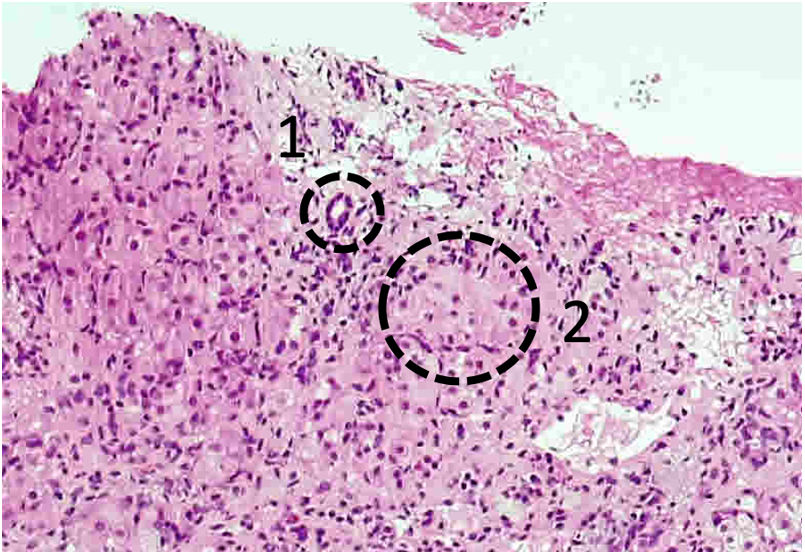

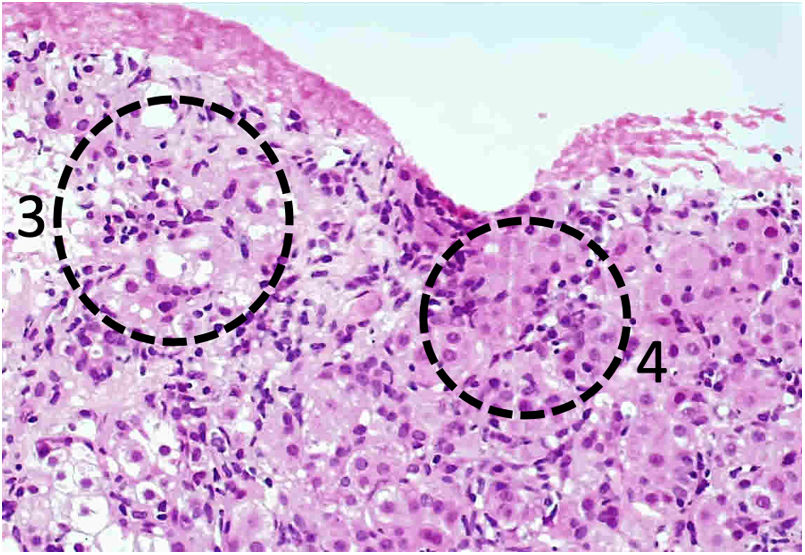

Case descriptionThe authors describe a 77-year old female patient, with no prior medical history, who was referred to our clinic due to persistently elevated liver enzymes. The patient reported mild abdominal discomfort and distension for the past 6 months. Blood tests showed: total bilirubin 4.53mg/dL (reference range – RR 0.20 to 1.0), conjugated bilirubin 3.33mg/dL (RR less than 20), aspartate transaminase (AST) 550UI/L (RR 15 to 37), alanine transaminase (ALT) 550UI/L (RR 16 to 63), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 212UI/L (RR 46 to 116), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 96UI/L (RR 35 to 64), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 310UI/L (RR 85 to 227). Imaging with abdominal ultrasound and triphasic computed tomography (CT) did not show any relevant changes. In addition to other aetiologies (namely, alcoholic, toxic, infiltrative, tumoral, granulomatous and infectious), which were ultimately excluded, we considered the possibility of an autoimmune liver disease. Further tests showed: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 72mm/h (RR less than 25), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) 1:320, immunoglobulin G (IgG) 4220mg/dL, with negative anti-DNA, antimitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle, anti-liver-kidney microsomal-1, anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas and anti-liver cytosol antibodies. A liver biopsy (Figs. 1 and 2) showed confluent necrosis, emperipolesis with moderate-to-severe interface hepatitis. These findings were suggestive of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis and the patient was started on prednisolone 0.5mg/kg/day, and, after two weeks, azathioprine, titrated to 1mg/kg/day, with simultaneous steroid tapering. The authors did not find any evidence of extra-hepatic manifestations or concurrent autoimmune disease. The patient was closely monitored for drug side effects, including diabetes, osteoporosis (having been started on prophylactic oral vitamin D and alendronic acid, due to a high FRAX score) and myelosuppression. After 30 months of treatment, with sustained clinical and biochemical remission (without undergoing another biopsy), the patient was waned of azathioprine, with no evidence of disease relapse. She is currently under close surveillance, with trimonthly appointments (with biochemical control) and biannual ultrasound.

Although the previous notion of autoimmune hepatitis as a disease of the young adult has been revised, it is rarely considered in the older patient with altered liver tests or cirrhosis of unknown aetiology. In fact, older patients tend to have a higher median of time until the diagnosis of AIH is established.3 Although few studies have been published on AIH in the elderly community, current evidence has shown than conventional treatment regimens appear to be highly effective.

This report is extremely relevant as it illustrates the need to consider this rare disease in the older patient, especially considering its high response rate to treatment and favourable prognosis when appropriately managed.

In addition, the authors wish to reiterate the need to adjust treatment regimens to the patient's age, constitution, comorbities and current medication. Most authors recommend lower doses of steroids during the induction phase, which have been shown to be equally effective and better tolerated by these patients (less or more). This patient responded very well to a lower dose of prednisolone (0.5mg/kg/day) and azathioprine (1mg/kg/day). Treatment-related complications (namely, diabetes and osteoporosis) must be prevented and appropriately managed.

Further studies are needed to accurately determine the most adequate treatment regimens for this subgroup of patients.

Funding sourceThere were no funding sources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.